Worrying signals from Petro’s Colombia

One worrying sign for FDI in Colombia was the lowering of Standard & Poor's creditworthiness gradingstandard from BB+ to a BB back in June 2025. This standard essentially measures the Colombian state’s reliability as an issuer of debt in its ability to pay back the interest and debt of all those who agree to invest in the country’s sovereign debt. Grading standards like this function as confidence meters for investors who look to invest in not only Colombian public debt but also in the country as a whole, by acting as a barometer for the financial responsibility and health of the state. Part of the issue that led to this lowering of the grade is the abandonment of the fiscal rule which establishes the legal limits for government deficits and public debt which was established by the law 1473 of 2011, and which had already been reformed in 2021 to broaden the limits during the pandemic.

This comes in the context of historically high public debt and deficit which although started and spiked during the pandemic has continued to rise in the last few years, from 2024 to 2025 government spending increased by 3.9%, from 503,244 billion COP to 523,007 billion COP. This could raise the national deficit from 6.25% of GDP in 2024 to 6.9% for 2025, as estimated by the IMF. The deficit reached levels below even the late 90s and only comparable to the pandemic years. This exceptional deficit is due in large part to the administration’s expansion in government subsidies, bureaucratic apparatus and state agencies, all part of Gustavo Petro’s political platform and strategy. This only appears to have been made worse by the government’s decision to raise the monthly minimum wage by 23% for 2026 onwards, which could increase government spending by 18,5% in the coming year.

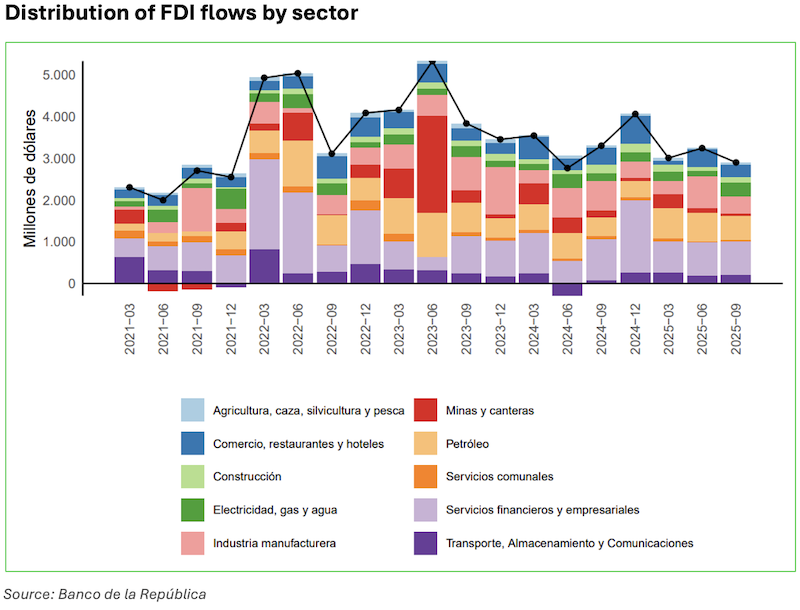

The economic issue of the administration’s spending-prone policies is not only relegated to the negative effects of a rising public debt and the concerning issue of investor confidence, but also the government’s attempts to ‘remedy’ the fiscal situation appears to be more damaging than beneficial. In line with his ideological doctrine Petro and his administration are very much partial to lowering the deficit by raising taxes in order to fund his political projects. This is reflected in the last tributary reform proposed by Finance Minister Germán Ávila to Congress in September, which seeks to raise 6,300 million USD in 2026 in order to help finance the rest of the governmental budget which totals 139,000 million USD. The proposed reform would raise the income tax on fossil fuel extraction companies by 15% (raising the total tax to 60%) and the taxes on dividends by 10% (raising the total to 30%); this would mean that in some cases a foreign investor would have to pay 54.5% tax on net business profits. For its part, his 2026 budget already represents an increase in government spending of 8.8% in relation to the previous budget, a decrease in debt repayment of 11%, and only a 5.3% increase in government investment (which could actually help boost economic activity).

Overall this paints a concerning fiscal picture of the current administration, one which has an oscillating but growing deficit and debt (national debt as percentage of GDP increasing from the pre-pandemic 51% to 61.9% in 2025), and seeks to remedy it with an increase to an already overbearing tax load on the sectors of the economy that would affect FDI the most; such as oil and mineral extraction and the financial sector. Of which if implemented, most of it would go to funding even more government bureaucracy and social programs and not on actually resolving the fiscal situation. Furthermore, this ‘solution’ of tax increases is not as straightforward as it would seem, since through economic concepts such as the Laffer Curve it can be seen that more taxes doesn’t equate to more revenue and can actually result in an overall reduction in tax revenue by promoting evasion, divestment and economic stagnation.

Another element that is important to analyze is the ongoing personal and diplomatic feud between Gustavo Petro and Donald Trump, and the effect of this on the erratic imposition and retraction of tariffs. In November the Trump administration removed the tariffs that it had imposed a month earlier on the import of grains coming from Colombia and reduced those for beef, tomatoes and plantains. This tariff would have had serious consequences for both the US and Colombian markets as Colombia is the 2nd largest exporter of coffee to the US, and the US is the largest buyer of Colombian coffee. This episode is only the latest thaw in a series of personal quarrels between the two heads of state that result in the imposition and later withdrawal of tariffs or other form of economic or diplomatic pressure. Just in October Trump had threatened to impose more tariffs in response to an argument with his Colombian counterpart over X.

This unpredictable and emotion-based back and forth has serious economic consequences, not only the direct imposition of tariffs, but also the shaking of confidence of US investors in Colombian industries such as coffee that their investments will be and remain profitable. This is particularly worrying in the context of FDI in Colombia, since as mentioned previously the largest foreign investment comes from the US and prejudicing this close economic relationship could have a serious impact on FDI in the Colombian economy. A fear that has grown since the latest and most acute Trump-Petro clash following Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro’s capture by US forces in January 2026.

Confidence perspective

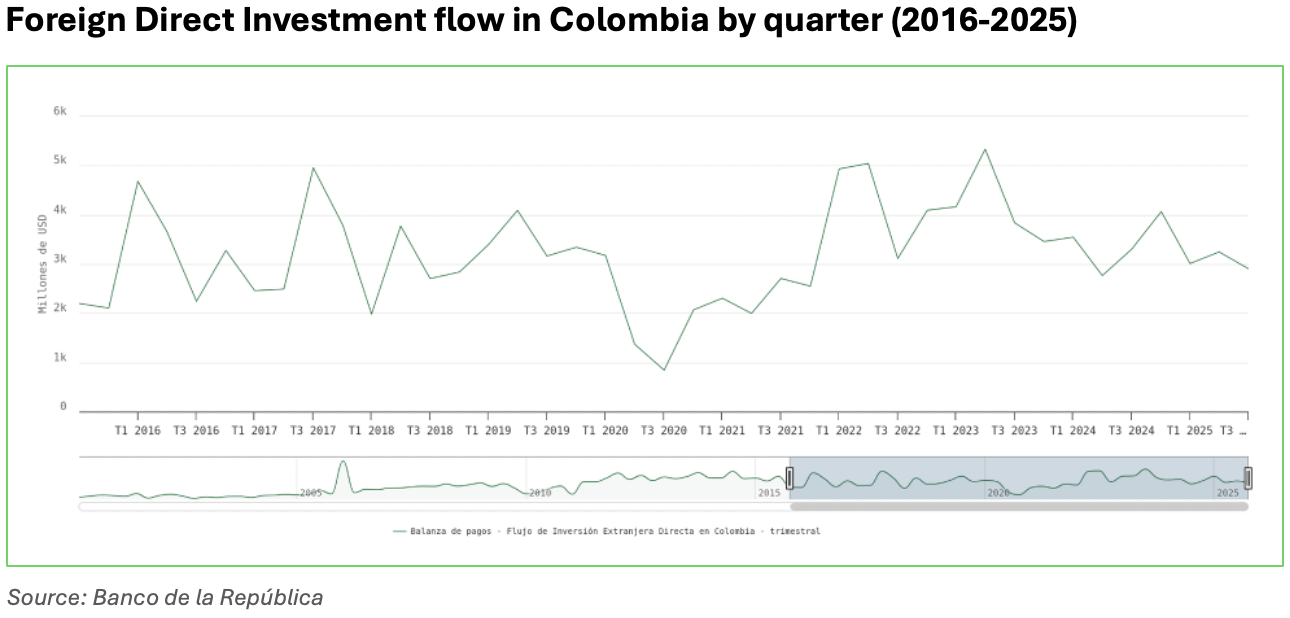

Despite all these concerning developments it is important to once again point out that the Colombian economy has recovered and seen growth since the pandemic, that likewise FDI has recovered to a significant degree. All in a very significant part due to the stability of and trust in Colombian political and financial institutions. It has been the independence of the Colombian legislature that has prevented the new tax reform prom being passed into law and it has been the independence of the central bank that has kept monetary policy stable and consistent with economic reality. While the full effects of Petro’s presidency on FDI can’t be seen at the moment they can be predicted by looking at those effects already observable throughout his term in office, which at least in terms of percentage of GDP might indicate a shift in confidence of foreign investors resulting in slower growth than expected.