In the image

The ‘Juan Carlos I’ L-61 aircraft carrier, flagship of the Spanish Navy, with two McDonnell Douglas EAV-8V ‘Matador II’, a modified version of the ‘Harrier II’ [Contando Estrellas]

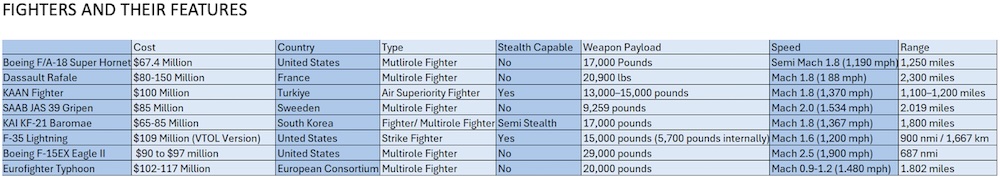

On August 7, 2025, Spain shocked its allies and the US when it announced that it would not purchase the Lockheed Martin F-35 to replace neither the aging F-18 ‘Hornet’ of its Air Forces, nor the AV-8 ‘Harriers’ of the Spanish Navy. While no definitive answer has been given for the future of the Spanish naval aviation, the Spanish Defense Minsitry instead announced that Spain would seek strategic autonomy by purchasing more Eurofighter ‘Typhoons’ and would be placing its hopes in the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) currently under development by a European consortium of German, French, and Spanish companies.

The decision has left the future of the air wing of the Spanish Navy on the medium term in doubt. In view of this situation, the Spanish Navy has opted to continue to extend the life of its fleet of ‘Harriers’ until the 2030s, by witch time the other two countries fielding this same aircraft, the United States and Italy, will have long retired it, complicating Spain’s acquisition of spare parts for the fighters. Meanwhile, for the Spanish Air and Space Force, the FCAS is a long term plan to gradually replace the F/A-18 ‘Hornets’ still in its inventory.

This article seeks to briefly analyze the current situation of the FCAS, the state of the Spanish Air Force and Navy, and the options the Spanish Air Force has left in case the program collapses, with their advantages and disadvantages. The article will finish with the conclusions and recomedations.

The situation

The decision of the Spanish government regarding the F-35 put an end to long standing speculation over the future of Spanish air power. While the Spanish Air Force had already pointed out that it would seek to acquire more Eurofighters, with an additional 35 fighters to be delivered by 2030 instead of the F-35 as replacements for the F-18s, the situation in regards to the Navy remains murky, with no clear options for the Navy to replace its ‘Harriers’ after the 2030 deadline.

The decision by the Spanish government has been contrary to that of other European nations like Denmark,Switzerland, or Belgium, which have decided to acquire the F-35 to bolster their air forces. It has come in the middle of diplomatic tensions between Madrid and Washington due to Spain’s lagging behind in contributions to NATO’s defense. During his first term in office, Trump had pressured NATO members to increase their defense contributions to NATO, the famous 2% GDP minimum. In 2025, at the beginning of President Trump’s second term, the situation has deteriorated for Spain, whose prime minister has been vocal in his opposition to the defense increases to reach 5% of the GDP of the allied states proposed by the Trump Administration and agreed by all members of the alliance in the NATO summit celebrated in The Hague in June, provocking in the way a diplomatic crisis with the Untied States, whose President, half-jokingly, suggested Spain had to bekicked out of NATO.

FCAS, GCAP and politics

As mentioned in the introduction, Spain ditched the F-35 for the FCAS for the Spanish Air Force. The FCAS is a program integrated by Germany, France, and Spain to produce a Sixth-Generation fighter that could work in tandem with a drone network and with advanced sensors. The Spanish Air Force had shown optimism for the program to replace the ageing F/A-18 ‘Hornets’ while the Spanish Navy, as mentioned before, was still hoping to acquire the F-35 to replace the ‘Harriers’.

However, in recent months, the FCAS program has entered a limbo, as challenges dating back as far as 2021have raised concerns over the future viability of the project. Rivalry between European aircraft manufacturers and those of the F-35 is not only limited to the FCAS: the French ‘Rafale’ is one of the main rivals to the F-35 in Europe.

The initial optimism that had been shown by the members of the FCAS has evaporated as the deadline of the FCAS to produce a prototype is approaching with little progress. The main issue at stake is the level of control of the project: France has demanded the control a staggering 80% of the project, according to some sources. This has cast a doubt over the future of the program. The French Dassault, one of the leading companies in the project, and the most experienced one, has been implying that it will develop its own Sixth Generation fighter as it has faced setbacks in negotiations. These are not empty threats, as Dassault is one of the strongest aviation industries and a source of pride in French aviation. That notwhistanding, France has downplayed the level of intensity of the dispute. As of November 2025, France has voiced willingness to seek a mutually acceptable solution.

Germany, responsible for the advanced sensors meant to give the fighter the ability to act as a command and control center for fleets of drones, has blamed the French for the delays and has delivered an ultimatum: either the differences are solved by the end of 2025, or FCAS is over. Germany’s ultimatum came as Airbus started to demand Dassault to be removed from the project. Spain, for its part, involved in the project through Indra, which proposed several projects for the FCAS, has continued to gamble on FCAS, while supporting Germany in keeping the project afloat. Spain has increased funding for the floundering program.

It is worth noting that this is not the first time France has wavered in Pan-European projects, despite being one of the proponents. For instance, France was not present in the projects that created the Panavia ‘Tornado’ or the Eurofighter ‘Typhoon’. Instead, France aimed to focus on the ‘Rafale’, which French President Emmanuel Macron refers to as the “Pan European” alternative to the F-35. It must be noted that the ‘Rafale’ is produced almost entirely by France, with little input of the rest of Europe.

As Spain and Germany continue to drag negotiations with France, other programs to replace fourth generation fighters are already making headway in Europe, with the most significant being the Global Combat Air Program (GCAP), a joint program conducted by the UK, Italy, and Japan to develop a new fighter, known as the ‘Tempest’, called to replace the Eurofighter ‘Typhoon’ by 2035. The United Kingdom is the senior partner in the GCAP program, with Italy and Japan handling component production, electronics and engines, as well as expertise.

Despite being two of the most important nations involved in the Eurofighter, the UK and Italy have started to shift their focus to the GCAP. While there are some indications that Eurofighter assembly lines will shift to production of the GCAP, the overall future of that aircraft is not in jeopardy. The UK has indicated that it will simultaneously produce ‘Typhoons’ and GCAP fighters. Some members of the Eurofighter program have also stated that they wish to double production by 2028, due to orders from Turkey and others. However, the production of the ‘Typhoon’ is slowing down in the UK as some factories are starting to shut down as orders from the Royal Air Force start to dry up.

With FCAS’ future uncertain, some have voiced that Germany and Spain could join GCAP, but without the economic benefits. On September 28th, the UK voiced willingness to let Germany into the GCAP, with ‘Tempest’ expected to make its first flight in 2027. Other comentators have speculated that Spain and Germany could pursue a separate project with Sweden. This is, however, unlikely because they do not own the technology required to produce a stealth aircraft, since France and Great Britain are the only European powers with the necessary know-how to do it. Beyond them, it is the United States who has pioneered stealth technology with Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works, responsible for iconic aircraft like the famous SR-71 ‘Blackbird’ and the F-22 ‘Raptor’. That is without mentioning the massive financial costs of designing, building, testing, and maintaining a stealth aircraft.

Spanish Air Force and Navy

Due to the political isolation Spain found itself in the aftermath of WW2, the Spanish armed forces found it hard to acquire modern military equipment. In response to political constraints, it adopted for its Air Force the policy of using a mixed fleet of American and European (French) aircraft, so if one was unable to be maintained for political constraints, Spain would have a Plan B. One example is Spain’s fleet of F/A-18 ‘Hornets’ and Eurofighter ‘Typhoons’.

As mentioned before, Spain placed its hopes in the now moribund FCAS program, leaving the future of the Spanish Air and Space Force in uncharted territory. Since the abandonment of the procurement of the F-35, speculation has run wild in the media over what alternatives Spain could acquire to replace the F/A-18 ‘Hornets’ and ‘Harriers’ and, in the future, the Eurofighter. The F/A-18 ‘Hornets’ entered into service in Spain in the 1980s and the Euroofighters in 2003. The Spanish Air Force has already sought to replace the ‘Hornets’, witch have become obsolete.

As for the Spanish Navy, it is one of the few in the world capable of operating fixed wing aircraft from carriers, in the form of the AV-8 ‘Harriers’ of the 9th Squadron that operates from the BAM ‘Juan Carlos I’. It was initially expected that Spain’s ‘Harrier’ force would be in service up until 2028; however, the decision was put off to 2030 after the decision not to purchase the F-35 made made.