Breaking through

Many are those who argue, however that great progress has been made in the field and steps like China’s leadership in electrolyser manufacturing (65% of global capacity at 2 gigawatts in 2024, plus over 1 gigawatt added in early 2025) and policy moves such as Europe’s quotas under the EU Renewable Energy Directive, India’s mandates for refining and fertilizers, and the IMO’s Net-Zero Framework for shipping, could bring big geopolitical changes, potentially reworking relationships, interdependencies, and balances of power.

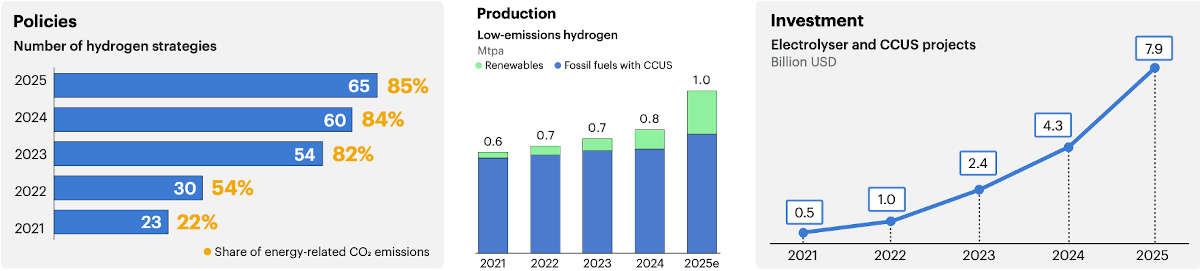

Recent policy examples would be an argument in favor of showing this speed-up: In January 2025, the US Department of Energy updated clean hydrogen efforts, emphasizing reliable energy and flexible rules for fuel cells. By April, though, the new US administration started reversing some Biden-era clean energy rules, which might slow things even as global commitments to hydrogen funding had passed over USD 110 billion, with 1,700 projects announced since 2020 and 50 now running, according to the IEA review. In aviation, 2025 brought forward rules for hydrogen projects, with groups calling for support to launch additional ones

The new hydrogen geopolitics

And what would all of this mean from a geopolitical perspective? For starters, the spread-out nature of renewables for green hydrogen could make energy access more democratic, boosting areas like North Africa, Australia, Chile, and Namibia as new ‘electro-states.’

Deals in ‘hydrogen diplomacy,’ like Germany’s agreements with Namibia and Morocco, or Japan’s with Australia, are building connections that skip old fossil fuel powers, making trade more regional (e.g., Africa-Europe pipelines or Latin America-Asia ammonia shipments) and reducing risks of weaponization through varied supply spots.

Moreover, since hydrogen is an energy carrier, meaning that it’s not a primary source, produced from widely available renewables, green hydrogen trade flows are less likely to face the same geopolitical pressures as oil and gas, whose limited reserves have long sparked conflicts and dependencies. This could create a ‘Distributed Energy Commonwealth,’ where countries gain more independence, reducing exposure to price jumps and political games. Joint research, tech sharing, and open rules could speed up new ideas, cutting needs for rare minerals like platinum and iridium, while supporting fair growth in the Global South, making green hydrogen a means for lasting development, food safety (e.g., green ammonia for fertilizer-short areas in Sub-Saharan Africa), and regional unity. IRENA forecasts one-third of green hydrogen traded by 2050, half by pipelines and half as forms like ammonia, building new ties and helping over 50% of global energy needs from developing nations skip fossil reliance.

The Gulf States, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, are well-placed to benefit from this change, leveraging their big funds, current energy setups, and access to both renewables and gas to push a hydrogen economy that could stabilize their social and government systems while growing their world ambitions. Additionally, recent deals and visits point to a shift toward East Asia, especially Japan and South Korea, as primary buyers, instead of Europe, with projects like Saudi Arabia’s USD 5 billion Helios and the UAE’s ADNOC blue ammonia pacts with Japan and Korea. Japan and South Korea, guided by hydrogen plans (Tokyo’s ‘Basic Hydrogen Strategy’ and Seoul’s hydrogen roadmap), aim to reduce the amount of carbon in their economies, develop strong local industries, and achieve energy independence as land conflicts with China threaten the energy supply. Because of the scarcity of natural resources and space, both focus on imports, planning to get green hydrogen from Oman and blue from the UAE and Australia.

The risk of hydro-colonialism

Nevertheless, the idea that a geopolitical shift would come without challenges is ludicrous, and this is why many argue that the possibilities that stagnation would come about are quite high. In fact, they mention the likelihood of what they call a ‘hydro-colonialism’ system arising. The latter would essentially mirror the fossil fuel era’s unfairness and, most significantly, strengthen it via blue hydrogen’s staying power.

In fact, while green hydrogen offers spread-out power, blue's need for fossil raw materials means the sector isn't fossil-free, with raw natural gas and coal still ruling 99% of supply (using 290 billion cubic meters of gas and 90 million tons of coal equivalent in 2024, according to the IEA). This might delay big geopolitical changes, letting fossil-rich countries like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Russia, and Qatar switch easily: reusing gas setups for blue production, insuring against the loss of assets (which caused 1.6-notch credit drops for big exporters from 2015–2020), and securing export revenues (e.g., Russia eyeing 20% of the global market by 2030, or Saudi Arabia's Helios project in 2025). From a world politics view, low-carbon hydrogen from natural gas could lock in and extend these producers' influence, letting them hold onto old trade links and export routes instead of losing to new players.

The commercialization of CCS (carbon capture & sequestration), combined with a high level of natural gas reserves, will dictate the extent to which the fossil exporters are able to anchor themselves in the low-carbon markets. Existing and proposed CCS plants are mostly located in North America, Australia, northern Europe, the Gulf States, China, and Southeast Asia, with large extensions expected in Europe and Asia-Pacific by 2030, which may boost their dominance in blue hydrogen. The strategies employed by more than half of fossil exporters keep gas markets and import relationships and alliances (like the blue ammonia agreements of ADNOC with Japan and Korea), which could essentially continue emissions through methane releases and incomplete CCS and extend their influence. Also, the power of the electrolyser market, with a dominant presence of China, Europe, and Japan, might contribute to this, by having the presence of gatekeepers who reduce developing countries to being mere exporters of the raw energy, whilst water shortages in strategic spots (such as most of the projects to be developed in arid Australia, Chile and Oman) trigger local tensions over desalination brine and water rights.

Competing scenarios for 2040

Therefore, renewable energy resources, though less focused than fossils, add twists with longer, more tangled value and supply chains that spread out and connect deeply. Governments, public groups, and firms thus compete among each other not only for resources and transport paths but also for main markets, parts, making processes, industries, upkeep, investment cash, and funding, changing dependencies across the chain's map and raising complexity.

Old petro-states are adapting themselves to the new changes, but not evenly: failing to focus on green could weaken their power as oil/gas income drops (despite the unlikeliness of being fully replaced by hydrogen exports), while competing groups form around closed supply chains, sparking trade fights over minerals and rules. From the Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik‘s take, three likely world politics paths to 2040 show these strains: ‘Hydrogen Realignment’ sees teamwork toward varied, regional ties; ‘Hydrogen (In)Dependence’points out ongoing weak spots in split supply chains; and ‘Hydrogen Imperialism’ cautions against controlling groups using tech and resource gaps, stressing the call for active rules to dodge the last one.

To conclude, the hydrogen sector's latest gains, from more FIDs and policy launches to factory growth, mark a turning point, but one shadowed by blue hydrogen's links with fossils. Whether this leads to a more teamwork-based world order or one broken by lasting dependencies depends on the choices that are going to be made: establishing strong regulations before market divisions emerge (as IRENA urges, through clear emissions standards and open frameworks), fostering equitable partnerships to prevent exploitation, and accelerating the shift to green hydrogen for genuine diversification. As both the IEA and IRENA emphasize, boosting demand, developing infrastructure (such as repurposing gas pipelines), and supporting emerging economies through financing, technology sharing, and capacity building will be essential to manipulate the transition toward real progress rather than a continued dependence on fossil-based systems.