Breadcrumb

Blogs

Entries with Categorías Global Affairs Asia .

Primer encuentro de alto nivel EEUU-China de la era Biden, celebrado en Alaska el 18 de marzo de 2021 [Dpto. de Estado]

ENSAYO / Ramón Barba

El presidente Joe Biden está construyendo con cautela su política para el Indo-Pacífico, buscando construir una alianza con India sobre la que construir un orden que contrarreste el auge chino. Tras su entrada en la Casa Blanca, Biden ha mantenido el foco de atención en esta región, aunque con un enfoque diferente al de la Administración Trump. Si bien es cierto que el objetivo principal sigue siendo contener a China y defender el libre comercio, Washington está optando por un acercamiento multilateral que otorga mayor protagonismo al QUAD[1] y cuida especialmente la relación con India. Como abanderada del mundo libre y de la democracia, la Administración Biden pretende renovar el liderazgo estadounidense en el mundo y particularmente en esta decisiva región. No obstante, aunque la relación con India se encuentra en un buen momento, especialmente teniendo en cuenta la firma del acuerdo BECA[2] alcanzado al final de la Administración Trump, la interacción entre ambos países está lejos de consolidar una alianza.

La nueva presidencia de Estados Unidos se encuentra con un puzle muy complicado de resolver en Indo-Pacífico, cuyos principales actores son China y la India. Por lo general, nos encontramos con que, de las tres potencias, solo Pekín ha sabido gestionar con éxito la situación post-pandemia[3], mientras que Delhi y Washington siguen enfrentando una crisis tanto sanitaria como económica. Todo ello puede afectar a la relación entre India y Estados Unidos, en especial en lo comercial[4], no obstante, y a pesar de que Biden aún no ha demostrado cuál va a ser su estrategia en la región, todo parece que la relación entre ambas potencias va a ir a más[5]. Sin embargo, a pesar de que Estados Unidos quiere llevar a cabo una política de alianzas multilateral y profundizar en su relación con la India, la Administración Biden deberá tener en cuenta diversas dificultades antes de poder hablar de una alianza como tal.

Biden comenzó a actuar en esta dirección desde el primer momento. En primer lugar estuvo en febrero la reunión del QUAD[6], que algunos consideran una mini OTAN[7] para Asia, en la que se discutieron cuestiones relativas a la distribución de la vacuna en Asia (pretendiendo distribuir un billón de dosis en 2022), la libertad de navegación en los mares de la región, la desnuclearización de Corea del Norte y la democracia en Myanmar. Además, el Reino Unido parece estar mostrando un interés mayor en la región y en este grupo de diálogo. Por otro lado, a mediados de marzo hubo una reunión en Alaska[8] entre las diplomacias de China y de Estados Unidos (encabezadas, respectivamente, por Yang Jiechi, director de la Comisión Central de Asuntos Exteriores, y Antony Blinken, secretario de Estado), en la cual ambos países se reprocharon duramente sus políticas. Washington se mantiene firme en sus intereses, aunque abierto a cierta colaboración con Pekín, mientras que China insiste en rechazar cualquier injerencia en lo que considera sus asuntos internos. Por último, cabe mencionar que Biden parece estar dispuesto a organizar una cumbre de democracias[9] en su primer año de mandato.

Tras los contactos que también hubo en Alaska entre los titulares de Defensa de China y de Estados Unidos, Austin Lloyd[10], jefe del Pentágono, visitó la India para remarcar la importancia de la cooperación indo-estadounidense. Además, a comienzos de abril se produjo la participación de Francia en las maniobras navales La Pérouse[11] en la Bahía de Bengala, dando lugar a la posibilidad de un QUAD-plus en el que, además de las cuatro potencias originales, se integren también otros países.

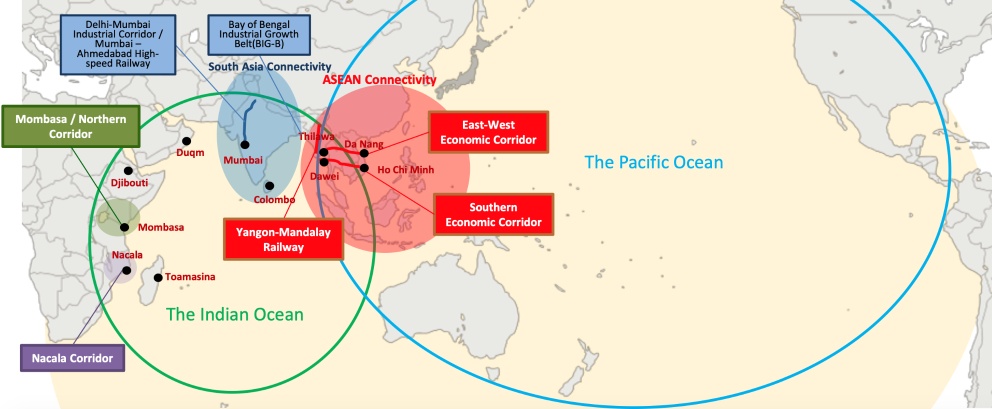

El Indo-Pacífico recordemos, se asienta como el presente y el futuro de las relaciones internacionales debido a su importancia económica (sus principales actores, India, China y EEUU representan el 45% del PIB mundial), demográfica (albergando un 65% de la población de todo el Globo) y, como veremos a lo largo del presente artículo, geopolítica[12].

Las relaciones entre EEUU, China e India

La Administración Biden parece ser continuista con la línea seguida por Trump, puesto que los objetivos no han variado. Lo que sí que cambia es el acercamiento hacia el objeto de la cuestión, que en este caso no es otro que la contención de China y la libertad de navegación en la región, ahora bien, en base a una gran apuesta por el multilateralismo. Como bien dijo el nuevo sucesor de George Washington en su toma de posesión[13], Estados Unidos quiere retomar su liderazgo, pero de una manera diferente a la de la Administración anterior; esto es, mediante una fuerte política de alianzas, un liderazgo moral y una fuerte defensa de valores como la dignidad, los derechos humanos y el Estado de Derecho.

La nueva presidencia concibe a China como un rival para tener en cuenta[14], al igual que la Administración Trump, pero no ve esto como un juego de suma cero, puesto que, aunque declara abiertamente estar en contra de la actuación de Xi, abre la puerta al diálogo[15] en materias como el cambio climático o la sanidad. Por lo general, en línea con lo visto en Nuevas tensiones en Asia Pacífico[16], Estados Unidos apuesta por un multilateralismo que busca rebajar la tensión. Recordemos que Estados Unidos propugna la defensa de la libre navegación y el Estado de Derecho, así como de la democracia en una región en la que está viendo mermada su influencia por el creciente peso de China.

Para entender bien el estado de las relaciones entre Estados Unidos, China e India cabe que remontarse a 2005[17], cuando todo parecía ir bien. En lo relativo a la relación sino-india, ambas naciones habían resuelto sus disputas motivo de los ensayos nucleares de 1998; además, su presencia en foros regionales era creciente y parecía que la cuestión relativa a las disputas transfronterizas comenzaba a arreglarse. Por su parte, Estados Unidos gozaba de buenas relaciones comerciales con ambos países. Sin embargo, el cambio de patrones en la economía mundial, motivado por el auge de China; la crisis financiera de 2008, surgida en Estados Unidos, y la inhabilidad de India para mantener la tasa de crecimiento rompieron este equilibrio. A ello contribuyó la actitud tirante de Donald Trump. No obstante, hay quien argumenta que la rotura del orden posterior a la Guerra Fría en Asia Pacífico comenzó con el “pivote hacia Asia”[18] de la Administración Obama. A ello hay que añadir los pequeños roces que China ha tenido con ambas naciones.

Brevemente, cabe mencionar que entre India y China existen problemas fronterizos[19] que a partir de 2013 se han ido reavivando. A su vez, India es contraria a la hegemonía china; no quiere verse subyugada por Pekín y apuesta claramente por el multilateralismo. Finalmente, existen problemas en lo relativo al dominio marítimo debido a que el Estrecho de Malaca está al límite de su capacidad. Además, Delhi reclama como suyas las islas Adaman y Nicobar, en la ruta de acceso a Malaca. Es más, como India ahora se encuentra muy por debajo del poder militar y económico de China[20] –roto el equilibrio que había entre las dos potencias en 1980–, intenta poner trabas a Pekín para así contenerle.

Estados Unidos mantiene roces de tipo ideológico con China, debido al carácter autoritario del régimen de Xi Jinping[21], y comercial, en una pugna[22] que Pekín pretende aprovechar para aminorar la influencia estadounidense en la zona. En medio de este conflicto está India, que apoya a Estados Unidos puesto que, aunque no parece querer estar del todo en contra de China[23], rechaza una hegemonía regional china[24].

Según el último informe del CEBR[25], China superará a Estados Unidos como potencia mundial en 2028, antes de lo previsto en proyecciones anteriores, en parte gracias a cómo ha gestionado la emergencia del coronavirus: ha sido el único gran país que tras la primera oleada ha evitado una crisis. Por otro lado, Estados Unidos ha perdido la batalla contra la pandemia; se espera que se crecimiento económico entre 2022-2024 sea del 1.9% del PIB y se reduzca al 1.6% en los siguientes ejercicios[26], mientras que China, según el informe estará entre 2021-2025 creciendo al 5.7%[27].

Para China la pandemia ha sido una forma de indicar su lugar en el mundo[28], una manera de avisar a Estados Unidos de que está lista para tomar el testigo como líder de la comunidad internacional. A ello cabe aunarle la actitud beligerante de China en la región de Asia Pacífico, así como su crecimiento hegemónico en la zona y proyectos comerciales con África y Europa. Todo ello ha llevado a desequilibrios en la región que implican los movimientos de Washington en lo relativo al QUAD. Recordemos que, a pesar de su rol menguante como potencia, a Estados Unidos le interesa la libertad de navegación por razones tanto comerciales como militares[29].

Así pues, el auge económico chino ha dado lugar a un empeoramiento de la relación entre Washington y Pekín[30]. Además, aunque Biden apuesta por la cooperación en lo relativo a la pandemia y al cambio climático, desde algunos sectores de la política americana se habla de una competición inevitable entre ambos países[31].

El grado de alianza entre EEUU e India

En línea con lo expuesto anteriormente podemos observar que nos movemos en tesituras delicadas, tras el cambio en la Casa Blanca. Enero y febrero han sido meses de pequeños movimientos por parte de Estados Unidos e India, que no han dejado indiferente a China. Aunque la relación chino-estadounidense ha beneficiado a ambas partes desde su inicio (1979)[32], creciendo el comercio entre ambos países en un 252% desde entonces, la realidad es que ahora los niveles de confianza están por los suelos, habiendo suspendido más de 100 mecanismos de diálogo entre ellos. Por lo tanto, aunque no se prevé un conflicto, sí que se pronostica un aumento de la tensión ya que, lejos de poder cooperar en amplios campos, por el momento solo parecen viables cooperaciones leves y limitadas. A su vez, recordemos que China se ve muy afectada por el Dilema de Malaca[33], por lo que busca otros accesos al Océano Índico, dando lugar a disputas territoriales con la India, con quien ya tiene el problema territorial de Ladakh[34]. En medio de esta Trampa de Tucídides[35], en la que China parece amenazar con superar a Estados Unidos, Washington se ha ido acercando a Nueva Delhi.

Por consiguiente, ambos países han ido desarrollando una colaboración estratégica[36], basada esencialmente en seguridad y defensa, pero que Estados Unidos busca ampliar a otras áreas. Bien es cierto que los problemas de Delhi están en el Índico y los de Washington en el Pacífico; sin embargo, ambos tienen a China[37] como denominador común. Su relación, además, se ve muy marcada por la ya expuesta “crisis tripartita”[38] (sanitaria, económica y geopolítica).

A pesar de la intensa cooperación entre Washington y Nueva Delhi, encontramos dos puntos de vista diferentes en lo relativo a este “partnership”. Mientras que desde Estados Unidos se afirma que India es un aliado muy importante, con el que comparte mismo sistema político y una intensa relación comercial[39], India prefiere una alianza menos estricta. Tradicionalmente, desde Delhi se ha transmitido una política de no alineamiento[40] en materias internacionales. De hecho, aunque India no quiere una supremacía China en el Indo-Pacífico, tampoco desea alinearse directamente contra Pekín, con quien comparte más de 3.000 km de frontera. No obstante, desde Delhi se ve muy necesaria la cooperación con Washington en materia de seguridad y defensa. De hecho, hay quien afirma que hoy la India necesita a EEUU más que nunca.

Si bien el pasado febrero, desde Washington se comenzó a revisar la Estrategia de Posición Global de Estados Unidos, todo apunta a que la Administración Biden continuará la línea de Trump en lo relativo a la colaboración con India como forma de contener a China. Sin embargo, aunque Washington habla de India como su aliado, por parte de Delhi hay ciertas reticencias, hablando pues de un alineamiento[41] más que de una alianza. Aunque la realidad que vivimos dista de la de la Guerra Fría[42], este nuevo containment[43] en el que se busca a Delhi como base, apoyo y estandarte, se ve materializado en lo siguiente:

i) Una intensa cooperación en materia de Seguridad y Defensa

Aquí existen distintos foros y acuerdos. En primer lugar, el ya mencionado QUAD[44]. Esta nueva alianza de cooperación multilateral que comenzó a gestarse en 2006[45] acordó en su reunión de marzo el desarrollo de su diplomacia de vacunas, con India como eje para así contrarrestar la exitosa campaña internacional llevada por Pekín en este campo. De hecho, hubo el compromiso de emplear 600 millones para repartir 1.000 millones de vacunas[46] en 2022. La idea es que Japón y EEUU financien la operación[47], mientras que Australia se encarga de la logística. No obstante, India apuesta por un mayor multilateralismo en el Indo-Pacífico, dando entrada a países como Inglaterra o Francia[48], que ya participaron en los últimos Diálogos de Raisina junto con el QUAD. A lo largo de la reunión también se trataron otros temas como la desnuclearización de Corea, la restauración democrática de Myanmar y el cambio climático[49].

India busca contener a China, pero sin provocar un enfrentamiento directo con China[50]. De hecho, Pekín ha dado a entender que de ir las cosas más allá, no solo India sabe jugar a la Realpolitk. Recordemos que Nueva Delhi va a presidir este año la reunión con los BRICS. Además, la Shanghai Cooperation Organization va a acoger ejercicios militares conjuntos de China y Pakistán, país de compleja relación con India.

Por otro lado, en su viaje de marzo a India, el jefe del Pentágono[51] trató con su homólogo Rajnath Singh sobre el incremento de la cooperación militar, así como de asuntos relacionados con la logística, el intercambio de información, posibles oportunidades de asistencia mutua y la defensa de la libre navegación. Lloyd afirmó no ver con malos ojos que Australia y Corea participen como miembros permanentes en los ejercicios Malabar. Desde 2008 el comercio en materia militar entre Delhi y Washington suma 21 billones de dólares[52]. Además, recientemente, se han gastado 3000 de dólares en drones y otro material aéreo para misiones de reconocimiento y vigilancia.

Una semana después esta reunión, dos barcos indios y uno estadounidense realizaron un ejercicio marítimo de tipo PASSEX[53] como forma de consolidar las sinergias e interoperabilidad alcanzadas en el ejercicio de Malabar del pasado noviembre.

En este contexto, cabe hacer una mención especial a la plataforma de diálogo 2+2 y al ya mencionado BECA (Acuerdo Básico de Intercambio y Cooperación para la cooperación en materia geoespacial). El primero, es un tipo de reunión en la que los titulares de Exteriores y Defensa de ambos países se reúnen cada dos años para tratar de temas que les sean de interés. La reunión más reciente tuvo lugar en octubre de 2020[54]. En ella no solo se acordó el BECA, sino que Estados Unidos se reafirmó en su apoyo a India en lo relativo a sus problemas territoriales con China. A su vez, también se firmaron otros memorándums de entendimiento sobre cuestiones de energía nuclear y climáticas.

El BECA, firmado en octubre de 2020 durante los últimos meses de la Administración Trump, facilita a India localizar mejor a enemigos, terroristas y otro tipo de amenazas que vengan desde tierra o desde mar. Con este acuerdo se pretende consolidar la amistad que hay entre ambos países, así como ayudar a India a superar tecnológicamente a China. En virtud de este acuerdo se concluye la “troika de pactos fundacionales” para una profunda cooperación en seguridad y defensa entre ambos países[55].

Antes de este acuerdo, en 2016 se firmó el LEMOA (Memorando de Acuerdo para el Intercambio de Logística), y en 2018 el COMCASA (Acuerdo de Compatibilidad y Seguridad de las Comunicaciones). El primero permite a ambos países acceso a las bases de cada uno para abastecimiento y reposición; el segundo permite a India recibir sistemas, información y comunicación encriptada para comunicarse con Estados Unidos. Ambos acuerdos afectan a los ejércitos de tierra, mar y aire[56].

ii) Unidos por la democracia

Desde Washington se pone especial énfasis en que ambas potencias son muy semejantes, puesto que comparten el mismo sistema político, y se destaca con cierta grandilocuencia que conforman la democracia más antigua y la más grande (por número de habitantes)[57]. Debido a que eso presupone compartir una serie de valores, Washington gusta hablar de “likeminded partners”[58].

Desde el think tank Brookings Institution, Tanvi Mandan defiende esta idea de ligazón ideológica. El mismo sistema de gobierno hace que ambos países se vean como aliados naturales, que piensan igual y que además creen en el valor del imperio de la ley. De hecho, en todo lo relativo a la extensión de la democracia por el globo, hay una fuerte cooperación entre ambas naciones: por ejemplo, apoyando la democracia en Afganistán o en Maldivas, lanzando la US-India Global Democracy Iniciative y dotando de asistencia legal y técnica en cuestiones democráticas a otros países. Finalmente cabe resaltar que la democracia y los valores que acarrea han facilitado el intercambio y flujo de personas de un país a otro. En cuanto a la relación económica entre ambos países se vuelve más viable, puesto que los dos son economías abiertas, comparten una lengua y su sistema jurídico tiene raigambre anglosajona.

iii) Creciente cooperación económica

Estados Unidos es el principal socio comercial de India, con quien tiene un importante superávit[59]. Los intercambios entre ambos han crecido un 10% anual a lo largo de la última década, y en 2019 fueron de 115.000 millones de dólares[60]. Alrededor de 2.000 empresas estadounidenses están instaladas en India, y unas 200 empresas indias se hallan en EEUU[61]. Entre ambos existe un Mini-Trade Deal, que se cree que será firmado en breve, y que tiene por objeto ahondar en esta relación económica. Con motivo de la pandemia, todo lo relativo al ámbito sanitario tiene un papel importante[62]. De hecho, a pesar de que ambos países han adoptado recientemente una actitud proteccionista, la idea es alcanzar 500.000 millones de dólares en comercio[63].

Divergencias, retos y oportunidades para India y EEUU en la región

Brevemente, entre los líderes de ambos países hay pequeños roces, oportunidades y retos a matizar para hacer de esta relación una fuerte alianza. Dentro de los puntos de conflicto, destacamos la compra desde India de misiles S-400 a Rusia, lo cual va en contra del CAATSA (Countering America’s Adversaries trhough Sanctions Act) [64], por lo que puede que India reciba una sanción, aunque en la reunión entre Sigh y Lloyd, este pareció pasar el tema por alto[65]. Sin embargo, cabe ver qué pasa una vez lleguen los misiles a Delhi. También existen pequeñas divergencias en lo relativo a libertad de expresión, seguridad y derechos civiles, y cómo relacionarse con países no democráticos[66]. Dentro de los retos que ambos países deben tener en cuenta, está la posible pérdida de apoyo en algunos sectores de la política estadounidense a la relación con India. Ello se debe a las actuaciones de India en Cachemira en agosto de 2019, la protección de la libertad religiosa y el trato a la disidencia. Por otro lado, en el caso contrario no ha faltado el debilitamiento de las normas democráticas, restricciones a la inmigración y violencia contra naturales de India[67].

En último lugar, recordemos que ambos se enfrentan a una profunda crisis sanitaria y por consiguiente económica, cuya resolución será determinante en relación con la competición con Pekín[68]. La crisis ha afectado a la relación bilateral puesto que, aunque el comercio en servicios se ha mantenido estable (alrededor de los 50.000 millones), el comercio de bienes decayó de 92.000 a 78.000 millones entre 2019 y 2020, aumentando el déficit comercial indio[69].

Para finalizar, cabe mencionar las oportunidades. En primer lugar, ambos países pueden desarrollar resiliencia democrática en el Indo-Pacífico así como en un orden internacional basado en normas[70]. En seguridad y defensa, también hay oportunidades como la entrada de Reino Unido y Francia como aliados en la zona, por ejemplo intentando que ambos países entren en el ejercicio de Malabar o que Francia presida el Indian Ocean Naval Simposium de 2022[71]. Aunque la tendencia a medio plazo es de cooperación entre Estados Unidos e India, la competencia con Rusia será una amenaza creciente[72], por lo que la cooperación entre Estados Unidos, India y Europa es muy importante.

También se abre la posibilidad de cooperación en mecanismos de MDA (Alerta del Entorno Marítimo) y ASW (Guerra Anti Submarina), en tanto que el Océano Índico reviste una importancia general para varios países debido al valor de sus rutas de transporte energético. Se abre la posibilidad de la cooperación mediante el uso de la Aeronave US P-8 “Poseidón”. A pesar de las disputas sobre el archipiélago de Chagos, India y Estados Unidos deberían aprovechar los acuerdos que tienen sobre islas como Andamán o Diego García para la realización de estas actividades[73]. Por lo tanto, India debería usar los organismos y grupos de trabajo regionales para cooperar con los países europeos y Estados Unidos[74].

Europa parece adquirir una creciente importancia debido a la posibilidad de entrar en el juego del Indo-Pacífico mediante el QUAD Plus. Los países europeos están muy a favor del multilateralismo, de la defensa de la libertad de navegación y del papel de las normas para regularla. Si bien es cierto que la UE ha firmado recientemente un tratado de comercio con China recientemente -el CAI-, incrementar la presencia europea en la región adquiere mayor importancia, puesto que el autoritarismo de Xi y sus actuaciones en Tíbet, Xinjiang, o el centro de China no son plato de buen gusto para los países europeos[75].

En último lugar, cabe recordar que hay algunas voces que hablan de un decaimiento o debilitamiento de la globalización[76], en especial tras la epidemia del coronavirus[77], por lo cual reavivar los intercambios multilaterales mediante la acción conjunta se convierte en un reto y en una oportunidad para ambos países. De hecho, se cree que a corto plazo las tendencias proteccionistas, al menos en el ámbito de la relación sino-india van a continuar, a pesar de la intensa cooperación económica[78].

Conclusión

El panorama geopolítico del Indo-Pacifico es cuanto menos complejo. El expansionismo chino choca con los intereses de la otra gran potencia regional, India, que si bien evita enfrentarse a Pekín ve con malos ojos la actuación de su vecino. En una apuesta por el multilateralismo, y con la mirada puesta en sus aguas regionales, amenazadas por el Dilema de Malaca, la India parece cooperar con Estados Unidos, pero aferrándose a los foros y grupos regionales para dejar clara su postura, mientras parece abrir la puerta a los países europeos, cuyo interés en la región va en aumento, a pesar del reciente tratado comercial firmado con China.

Por otro lado, también Estados Unidos se ve amenazado por el expansionismo chino y ve acercarse el momento del sorpasso económico de su rival, que la crisis del coronavirus pude haber adelantado incluso a 2028. En aras de evitar tal situación, la Administración Biden apuesta por el multilateralismo a nivel regional y ahonda en su relación con India, más allá de lo militar. Desde Washington parece haberse entendido que la hegemonía estadounidense en el Indo-Pacífico dista de ser real, al menos a medio plazo, por lo que solo cabe una actitud cooperativa e integradora. Por otro lado, en medio de este supuesto repliegue de la globalización, vemos cómo Washington junto con la India, y seguramente a medio plazo con Europa, hacen defensa de los valores occidentales que rigen en la esfera internacional, esto es, defensa de los derechos humanos, del estado de derecho y del valor de la democracia.

Estamos ante dos factores. Por un lado, India no quiere ver cómo se impone un orden de ningún tipo, ni americano ni chino, de ahí sus reticencias a enfrentarse directamente contra Pekín y su preferencia a expandir el QUAD. Por otro lado, Estados Unidos parece percibir encontrarse en un momento delicado, puesto que su competición con China va más allá de la mera sustitución de una potencia por otra. Washington no deja de ser una potencia tradicional que, para su presencia en el Indo-Pacífico, se ha servido sobre todo de poder militar, mientras que China ha basado la extensión de su influencia en el establecimiento de fuertes relaciones comerciales que van más allá de la lógica beligerante de la Guerra Fría. De ahí que Estados Unidos intente formar un frente con India y sus aliados europeos, que además vaya más allá de la cooperación militar.

REFERENCIAS

[1] El QUAD (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue), es un grupo de diálogo formado por los Estados Unidos, India, Japón y Australia. Sus miembros comparten una visión común sobre la seguridad de la región Indo-Pacífico contraria a la de China; abogan por el multilateralismo y la libertad de navegación en la región.

[2] BECA (Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement). Tratado firmado por la India y Estados Unidos en octubre de 2019 para mejorar la seguridad en la región del Indo-Pacífico. Su objetivo es el intercambio de sistemas de seguimiento, localización e inteligencia.

[3]Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, "Trilateral Perspective". Chinawatch. Conecting Thinkers.. http://www.chinawatch.cn/a/202102/05/WS60349146a310acc46eb43e2d.html, (accedido el 5 de febrero de 2021),

[4] Tanvi Madan,”India and the Biden Administration: Consolidating and Rebalancing Ties,” en Tanvi Madan, “India And The Biden Administration: Consolidating And Rebalancing Ties”,. German Marshal Found of the United States. https://www.gmfus.org/blog/2021/02/11/india-and-biden-administration-consolidating-and-rebalancing-ties, (accedido el 11 de febrero de 2021).

[5]Darshana Baruah, Frédéric Grére, y Nilanthi Samaranayake, "Agenda 2021: A Blueprint For U.S.-Europe-India Cooperation”, US-India cooperation on Indo-Pacific Security. GMF India Trilateral Forum. Pag:1. https://www.gmfus.org/blog/2021/02/16/us-india-cooperation-indo-pacific-security , (accedido el 16 de febrero de 2021).

[6] “’QUAD’ Leaders Pledge New Cooperation on China, COVID-19, Climate”. Aljazeera.com. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/12/quad-leaders-pledge-new-cooperation-on-china-covid-19-climate (accedido en marzo 2021)

[7] Mereyem Hafidi, "Biden Renueva La Alianza De ‘QUAD’ A Pesar De Las Presiones De Pekín". Atalayar. https://atalayar.com/content/biden-renueva-la-alianza-de-%E2%80%98QUAD%E2%80%99-pesar-de-las-presiones-de-pek%C3%ADn. (accedido en febrero de 2021)

[8] “`Grandstanding`: US, China trade rebukes in testy talks". Aljazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/19/us-china-top-diplomats-trade-rebukes-in-testy-first-talks (accedido, marzo 2021)

[9] Joseph R. Biden, “Why America Must Lead Again”. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again (accedido febrero, 2021).

[10] Maria Siow. "India Receives US Defence Secretary With China On Its Mind". South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3126091/india-receives-us-defence-secretary-lloyd-austin-china-its-mind. (accedido, 19 de marzo de 2021)

[11] Seeram Chaulia, “France and sailing toward the ‘QUAD-plus’”. The New Indian Express. https://www.newindianexpress.com/opinions/2021/apr/06/france-and-sailing-toward-the-QUAD-plus-2286408.html (accedido, 4 de abril, 2021)

[12] Juan Luis López Aranguren. “Indo-Pacífico: El nuevo orden sin China en el centro”. El Indo-Pacífico como nuevo eje geopolítico mundial. Global Affairs Journal. Pág.:2. https://www.unav.edu/web/global-affairs/detalle/-/blogs/indo-pacifico-el-nuevo-orden-sin-china-en-el-centro?_33_redirect=%2Fen%2Fweb%2Fglobal-affairs%2Fpublicaciones%2Finformes. (accedido, Abril 2021).

[13] Biden, "Remarks By President Biden On America's Place In The World | The White House"..

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/02/04/remarks-by-president-biden-on-americas-place-in-the-world/

[14] Íbid.

[15] Derek Grossman, "Biden's China Reset Is Already On The Ropes". Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Biden-s-China-reset-is-already-on-the-ropes. (accedido, 14 de marzo de 2021)

[16] Ramón Barba Castro, “Nuevas tensiones en Asia Pacífico en un escenario de cambio electoral”. Global Affairs and Strategic Studies. https://www.unav.edu/web/global-affairs/detalle/-/blogs/nuevas-tensiones-en-asia-pacifico-en-un-escenario-de-cambio-electoral-en-eeuu. (accedido, abril 2021)

[17] Sankaran Kalyanaraman, "Changing Pattern Of The China-India-US Triangle”. Manohar Parrikar Institute For Defence Studies And Analyses. https://www.idsa.in/idsacomments/changing-pattern-china-india-us-triangle-skalyanaram (accedido, marzo 2021)

[18] Pang Zhongying, "Indo-Pacific Era Needs US-China Cooperation, Not Great Power Conflict". South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3125926/indo-pacific-needs-us-china-cooperation-not-conflict-QUAD (accedido el 19 de marzo de 2021)

[19] Sankaran Kalayanamaran, “Changing Pattern of the China-India-US Triangle”.

[20] Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, “Trilateral Perspective”.

[21] Joseph R. Biden, “Remarks By President Biden On America’s Place In The World

[22]Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, “Trilateral Perspective”.

[23] Maria Siow, “India Receives US Defence Secretary With China On Its Mind”.

[24]Tanvi Madan, “India and the Biden Administration: Consolidating And Rebalancing Ties”.

[25] CEBR (Centre for Economics and Business Research), es una entidad dedicada al análisis y predicción económica de empresas y organizaciones. Enlace: https://cebr.com/about-cebr/ . Esta entidad elabora cada año un informe titulado World Economic League Table¸ en el que se analiza el posicionamiento en que tendrá cada país del Globo en lo relativo al estado de su economía. La última edición (World Economic League Table 2021), fue publicada el 26 de diciembre de 2020, este presenta una predicción del estado de la economía mundial en 2035, para así saber quienes serán las principales potencias económicas mundiales. (CEBR, “World Economic League Table 2021”. Centre for Economics and Business Research (12th edition), https://cebr.com/reports/world-economic-league-table-2021/ (accedido marzo 2021).

[26] Íbid., 231.

[27] Íbid., 71.

[28] Vijay Gokhale, “China Doesn’t Want a New World Order. It Wants This One”. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/04/opinion/china-america-united-nations.html. (accedido en abril de 2021)

[29] Mereyem Hafidi, “Biden renueva la Alianza de `QUAD` a pesar de las presiones de Pekín.

[30] Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, “Trilateral Perspective”.

[31] Íbid.

[32] Wang Huiyao, “More cooperation, less competition”. Chinawatch. Conecting Thinkers. http://www.chinawatch.cn/a/202102/05/WS6034913ba310acc46eb43e28.html. (accedido, marzo 2021).

[33] Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, “Trilateral Perspective”.

[34]Darshana Baruah, Frédéric Grére, y Nilanthi Samaranayake, “US-India cooperation on Indo-Pacific Security”. Page 5.

[35] Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, “Trilateral Perspective”.

[36] Ibid.

[37]Darshana Baruah, Frédéric Grére, y Nilanthi Samaranayake, “US-India cooperation on Indo-Pacific Security”. Page 5.

[38] Tanvi Madan, “India and the Biden Administration: Consolidating And Rebalancing Ties”

[39] Tanvi Madan, “Democracy and the US-India relationship”. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/democracy-and-the-us-india-relationship/ . (accedido, marzo 2021)

[40] Maria Siow, “India Receives US Defence Secretary With China On Its Mind”.

[41] Bilal Kuchay, “India, US sign key military deal, symbolizing closer ties”. Aljazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/11/2/india-us-military-deal. (accedido, marzo 2021)

[42] Wang Huiyao, “More cooperation, less competition”

[43] Alex Lo, “India-the democratic economic giant that disappoints”. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3126342/india-democratic-economic-giant-disappoints. (accedido, 21 de marzo de 2021)

[44] Simone McCarthy, “QUAD summit: US, India, Australia and Japan counter China’s ‘vaccine diplomacy’ with pledge to distribute a billion doses across Indo-Pacific”. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3125344/QUAD-summit-us-india-australia-and-japan-counter-chinas. (accedido, 13 de marzo de 2021)

[45]Mereyem Hafidi, “Biden renueva la Alianza de `QUAD` a pesar de las presiones de Pekín.

[46] Simone McCarthy, “QUAD summit: US, India, Australia and Japan counter China’s ‘vaccine diplomacy’ with pledge to distribute a billion doses across Indo-Pacific”.

[47] Aljazeera, “’QUAD’ leaders pledge new cooperation on China, COVID-19, climate”.

[48]Darshana Baruah, Frédéric Grére, y Nilanthi Samaranayake, “US-India cooperation on Indo-Pacific Security”. Page 2.

[49]Simone McCarthy, “QUAD summit: US, India, Australia and Japan counter China’s ‘vaccine diplomacy’ with pledge to distribute a billion doses across Indo-Pacific”.

[50] Maria Siow, “India Receives US Defence Secretary With China On Its Mind”.

[51] “US defense secretary Lloyd Austin says US considers India to be a great partner”. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/us-defense-secretary-lloyd-austin-says-us-considers-india-to-be-a-great-partner-101616317189411.html. (accedido, 21 de marzo de 2021)

[52] Maria Siow, “India Receives US Defence Secretary With China On Its Mind”.

[53] El término PASSEX es una abreviatura propia de la jerga militar inglesa, viene de Passing Exercise. Este, consiste en aprovechar que una unidad de marines pasa por una zona determinada para ahondar en la cooperación militar del ejército de esa zona por la que se está pasando. Como ejemplo encontramos la noticia citada en el presente artículo: “India, US begin two-day naval exercise in eastern Indian Ocean región”. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/india-us-begin-two-day-naval-exercise-in-eastern-indian-ocean-region/articleshow/81735782.cms (accedido, 28 de marzo de 2021)

[54] Annath Krishnan, Dinakar Peri, Kallol Bhattacherjee; India-U.S. 2+2 dialogue: U.S. to support India’s defence of territory. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-us-22-dialogue-rajnath-singh-raises-chinas-action-in-ladakh/article32955117.ece. (consultado, marzo 2021)

[55] Maria Siow, “India Receives US Defence Secretary With China On Its Mind”.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Tanvi Madan, “Democracy and the US-India relationship”

[58] Hindustan Times, “US defense secretary Lloyd Austin says US considers India to be a great partner”.

[59] “Committed to achieving goal of $500 bn in bilateral trade with US: Ambassador Sandhu”.The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/committed-to-achieving-goal-of-500-bn-in-bilateral-trade-with-us-ambassador-sandhu/articleshow/80878316.cms. (accedido, marzo 2021).

[60] Joe C. Mathew, “India-US mini trade deal: Low duty on medical devices; pact in final stages”. Business Today. https://www.businesstoday.in/current/economy-politics/india-us-mini-trade-deal-low-duty-on-medical-devices-pact-in-final-stages/story/413669.html. (Accedido, marzo de 2021)

[61] Economic Times, “Commited to achieving goal of $500 bn in bilateral trade with US: Ambassador Sandhu”.

[62] Joe C. Mathew, “India-US mini trade deal: Low duty on medical devices; pact in final stages”.

[63] Economic Times, “Commited to achieving goal of $500 bn in bilateral trade with US: Ambassador Sandhu”.

[64] Darshana Baruah, Frédéric Grére, y Nilanthi Samaranayake, “US-India cooperation on Indo-Pacific Security”. Page 2.

[65] “Hindustan Times “US defense secretary Lloyd Austin says US considers India to be a great partner”.

[66] Tanvi Madan, “Democracy and the US-India relationship”.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Tanvi Madan, “India and the Biden Administration: Consolidating and Rebalancing Ties”.

[69] Economic Times, “Commited to achieving goal of $500 bn in bilateral trade with US: Ambassador Sandhu”.

[70] Tanvi Madan, “Democracy and the US-India relationship”.

[71] Darshana Baruah, Frédéric Grére, y Nilanthi Samaranayake, “US-India cooperation on Indo-Pacific Security”. Page3.

[72] IBIDEM pag.3

[73] IBIDEM. Pag. 6

[74] IBIDEM. Pag. 7

[75] Seeram Chaulia, “France and sailing toward the ‘QUAD-plus’”. The New Indian Express

[76] Elisabeth Mearns, Gary Parkinson; “With a pandemic, populism and protectionism, have we passed peak globalization?”. China Global Television Network. https://newseu.cgtn.com/news/2020-05-28/With-a-pandemic-populism-and-protectionism-has-globalization-peaked--QOQMPg3ABO/index.html. (accedido, abril 2021).

[77] Abraham Newman, Henry Farrel; “The New Age of Protectionism”. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/europe/2021-04-05/new-age-protectionism. (accedido el 5 de abril de 2021)

[78] Economic Times, “Commited to achieving goal of $500 bn in bilateral trade with US: Ambassador Sandhu”.

Detainee in a Xinjiang re-education camp located in Lop County listening to “de-radicalization” talks [Baidu baijiahao]

Detainee in a Xinjiang re-education camp located in Lop County listening to “de-radicalization” talks [Baidu baijiahao]

ESSAY / Rut Noboa

Over the last few years, reports of human rights violations against Uyghur Muslims, such as extrajudicial detentions, torture, and forced labor, have been increasingly reported in the Xinjiang province's so-called “re-education” camps. However, the implications of the Chinese undertakings on the province’s ethnic minority are not only humanitarian, having direct links to China’s ongoing economic projects, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and natural resource extraction in the region. Asides from China’s economic agenda, ongoing projects in Xinjiang appear to prototype future Chinese initiatives in terms of expanding the surveillance state, particularly within the scope of technology. When it comes to other international actors, the Xinjiang dispute has evidenced a growing diplomatic split between countries against it, mostly western liberal democracies, and countries willing to at least defend it, mostly countries with important ties to China and dubious human rights records. The issue also has important repercussions for multinational companies, with supply chains of well-known international companies such as Nike and Apple benefitting from forced Uyghur labor. The situation in Xinjiang is critically worrisome when it comes to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly considering recent outbreaks in Kashgar, how highly congested these “reeducation” camps, and potential censorship from the government. Finally, Uyghur communities continue to be an important factor within this conversation, not only as victims of China’s policies but also as dissidents shaping international opinion around the matter.

The Belt and Road Initiative

Firstly, understanding Xinjiang’s role in China’s ongoing projects requires a strong geographical perspective. The northwestern province borders Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India, giving it important contact with other regional players.

This also places it at the very heart of the BRI. With it setting up the twenty-first century “Silk Road” and connecting all of Eurasia, both politically and economically, with China, it is no surprise that it has managed to establish itself as China’s biggest infrastructural project and quite possibly the most important undertaking in Chinese policy today. Through more and more ambitious efforts, China has established novel and expansive connections throughout its newfound spheres of influence. From negotiations with Pakistan and the establishment of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) securing one of the most important routes in the initiative to Sri Lanka defaulting on its loan and giving China control over the Hambantota Port, the Chinese government has managed to establish consistent access to major trade routes.

However, one important issue remains: controlling its access to Central Asia. One of the BRI’s initiative’s key logistical hubs is Xinjiang, where the Uyghurs pose an important challenge to the Chinese government. The Uyghur community’s attachment to its traditional lands and culture is an important risk to the effective implementation of the BRI in Xinjiang. This perception is exacerbated by existing insurrectionist groups such as the East Turkestan independence movement and previous events in Chinese history, including the existence of an independent Uyghur state in the early 20th century[1]. Chinese infrastructure projects that cross through the Xinjiang province, such as the Central Asian High-speed Rail are a priority that cannot be threatened by instability in the region, inspiring the recent “reeducation” and “de-extremification” policies.

Natural resource exploitation

Another factor for China’s growing control over the region is the fact that Xinjiang is its most important energy-producing region, even reaching the point where key pipeline projects connect the northwestern province with China's key coastal cities and approximately 60% of the province’s gross regional production comes from oil and natural gas extraction and related industries[2]. With China’s energy consumption being on a constant rise[3] as a result of its growing economy, control over Xinjiang is key to Chinese.

Additionally, even though oil and natural gas are the region’s main industries, the Chinese government has also heavily promoted the industrial-scale production of cotton, serving as an important connection with multinational textile-based corporations seeking cheap labor for their products.

This issue not only serves as an important reason for China to control the Uyghurs but also promotes instability in the region. The increased immigration from a largely Han Chinese workforce, perceived unequal distribution of revenue to Han-dominated firms, and increased environmental costs of resource exploitation have exacerbated the preexisting ethnic conflict.

A growing diplomatic split

The situation in Xinjiang also has important implications for international perceptions of Chinese propaganda. China’s actions have received noticeable backlash from several states, with 22 states issuing a joint statement to the Human Rights Council on the treatment of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang on July 8, 2019. These states called upon China “to uphold its national laws and international obligations and to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms”.

Meanwhile, on July 12, 2019, 50 (originally 37) other states issued a competing letter to the same institution, commending “China’s remarkable achievements in the field of human rights”, stating that people in Xinjiang “enjoy a stronger sense of happiness, fulfillment and security”.

This diplomatic split represents an important and growing division in world politics. When we look at the signatories of the initial letter, it is clear to see that all are developed democracies and most (except for Japan) are Western. Meanwhile, those countries that chose to align themselves with China represent a much more heterogeneous group with states from the Middle East, Asia, and Africa[4]. Many of these have questionable human rights records and/or receive important funding and investment from the Chinese government, reflecting both the creation of an alternative bloc distanced from Western political influence as well as an erosion of preexisting human rights standards.

China’s Muslim-majority allies: A Pakistani case study

The diplomatic consequences of the Xinjiang controversy are not only limited to this growing split, also affecting the political rhetoric of individual countries. In the last years, Pakistan has grown to become one of China’s most important allies, particularly within the context of CPEC being quite possibly one of the most important components of the BRI.

As a Muslim-majority country, Pakistan has traditionally placed pan-Islamic causes, such as the situations in Palestine and Kashmir, at the center of its foreign policy. However, Pakistan’s position on Xinjiang appears not just subdued but even complicit, never openly criticizing the situation and even being part of the mentioned letter in support of the Chinese government (alongside other Muslim-majority states such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE). With Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan addressing the General Assembly in September 2019 on islamophobia in post-9/11 Western countries as well as in Kashmir but conveniently omitting Uyghurs in Xinjiang[5], Pakistani international rhetoric weakens itself constantly. Due to relying on China for political and economic support, it appears that Pakistan will have to censor itself on these issues, something that also rings true for many other Muslim-majority countries.

Central Asia: complacent and supportive

Another interesting case study within this diplomatic split is the position of different countries in the Central Asian region. These states – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan – have the closest cultural ties to the Uyghur population. However, their foreign policy hasn’t been particularly supportive of this ethnic group with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan avoiding the spotlight and not participating in the UNHRC dispute and Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan being signatories of the second letter, explicitly supporting China. These two postures can be analyzed through the examples of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Kazakhstan has taken a mostly ambiguous position to the situation. Having the largest Uyghur population outside China and considering Kazakhs also face important persecution from Chinese policies that discriminate against minority ethnic groups in favor of Han Chinese citizens, Kazakhstan is quite possibly one of the states most affected by the situation in Xinjiang. However, in the last decades, Kazakhstan has become increasingly economically and, thus, politically dependent on China. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan implemented what some would refer to as a “multi-vector” approach, seeking to balance its economic engagements with different actors such as Russia, the United States, European countries, and China. However, with American and European interests in Kazakhstan decreasing over time and China developing more and more ambitious foreign policy within the framework of strategies such as the Belt and Road Initiative, the Central Asian state has become intimately tied to China, leading to its deafening silence on Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

A different argument could be made for Uzbekistan. Even though there is no official statistical data on the Uyghur population living in Uzbekistan and former president Islam Karimov openly stated that no Uyghurs were living there, this is highly questionable due to the existing government censorship in the country. Also, the role of Uyghurs in Uzbekistan is difficult to determine due to a strong process of cultural and political assimilation, particularly in the post-Soviet Uzbekistan. By signing the letter to the UNHCR in favor of China's practices, the country has chosen a more robust support of its policies.

All in all, the countries in Central Asia appear to have chosen to tolerate and even support Chinese policies, sacrificing cultural values for political and economic stability.

Forced labor, the role of companies, and growing backlash

In what appears to be a second stage in China’s “de-extremification” policies, government officials have claimed that the “trainees “in its facilities have “graduated”, being transferred to factories outside of the province. China claims these labor transfers (which it refers to as vocational training) to be part of its “Xinjiang Aid” central policy[6]. Nevertheless, human rights groups and researchers have become growingly concerned over their labor standards, particularly considering statements from Uyghur workers who have left China describing the close surveillance from personnel and constant fear of being sent back to detention camps.

Within this context, numerous companies (both Chinese and foreign) with supply chain connections with factories linked to forced Uyghur labor have become entangled in growing international controversies, ranging from sportswear producers like Nike, Adidas, Puma, and Fila to fashion brands like H&M, Zara, and Tommy Hilfiger to even tech players such as Apple, Sony, Samsung, and Xiaomi[7]. Choosing whether to terminate relationships with these factories is a complex choice for these companies, having to either lose important components of their intricate supply chains or face growing backlash on an increasingly controversial issue.

The allegations have been taken seriously by these groups with organizations such as the Human Rights Watch calling upon concerned governments to take action within the international stage, specifically through the United Nations Human Rights Council and by imposing targeted sanctions at responsible senior officials. Another important voice is the Coalition to End Forced Labour in the Uyghur Region, a coalition of civil society organizations and trade unions such as the Human Rights Watch, the Investor Alliance for Human Rights, the World Uyghur Congress, and the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, pressuring the brands and retailers involved to exclude Xinjiang from all components of the supply chain, especially when it comes to textiles, yarn or cotton as well as calling upon governments to adopt legislation that requires human rights due diligence in supply chains. Additionally, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, the same organization that carried out the initial report on forced Uyghur labor and surveillance beyond Xinjiang and within the context of these labor transfers, recently created the Xinjiang Data Project. This initiative documents ongoing Chinese policies on the Uyghur community with open-source data such as satellite imaging and official statistics and could be decidedly useful for human rights defenders and researchers focused on the topic.

One important issue when it comes to the labor conditions faced by Uyghurs in China comes from the failures of the auditing and certification industry. To respond to the concerns faced by having Xinjiang-based suppliers, many companies have turned to auditors. However, with at least five international auditors publicly stating that they would not carry out labor-audit or inspection services in the province due to the difficulty of working with the high levels of government censorship and monitoring, multinational companies have found it difficult to address these issues[8]. Additionally, we must consider that auditing firms could be inspecting factories that in other contexts are their clients, adding to the industry’s criticism. These complaints have led human rights groups to argue that overarching reform will be crucial for the social auditing industry to effectively address issues such as excessive working hours, unsafe labor conditions, physical abuse, and more[9].

Xinjiang: a prototype for the surveillance state

From QR codes to the collection of biometric data, Xinjiang has rapidly become the lab rat for China’s surveillance state, especially when it comes to technology’s role in the issue.

One interesting area being massively affected by this is travel. As of September 2016, passport applicants in Xinjiang are required to submit a DNA sample, a voice recording, a 3D image of themselves, and their fingerprints, much harsher requirements than citizens in other regions. Later in 2016, Public Security Bureaus across Xinjiang issued a massive recall of passports for an “annual review” followed by police “safekeeping”[10].

Another example of how a technologically aided surveillance state is developing in Xinjiang is the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP), a big data program for policing that selects individuals for possible detention based on specific criteria. According to the Human Rights Watch, which analyzed two leaked lists of detainees and first reported on the policing program in early 2018, the majority of people identified by the program are being persecuted because of lawful activities, such as reciting the Quran and travelling to “sensitive” countries such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Additionally, some criteria for detention appear to be intentionally vague, including “being generally untrustworthy” and “having complex social ties”[11].

Xinjiang’s case is particularly relevant when it comes to other Chinese initiatives, such as the Social Credit System, with initial measures in Xinjiang potentially aiding to finetune the details of an evolving surveillance state in the rest of China.

Uyghur internment camps and COVID-19

The implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Uyghurs in Xinjiang are pressing issues, particularly due to the virus’s rapid spread in highly congested areas such as these “reeducation” camps.

Currently, Kashgar, one of Xinjiang’s prefectures is facing China’s most recent coronavirus outbreak[12]. Information from the Chinese government points towards a limited outbreak that is being efficiently controlled by state authorities. However, the authenticity of this data is highly controversial within the context of China’s early handling of the pandemic and reliance on government censorship.

Additionally, the pandemic has more consequences for Uyghurs than the virus itself. As the pandemic gives governments further leeway to limit rights such as the right to assembly, right to protest, and freedom of movement, the Chinese government gains increased lines of action in Xinjiang.

Uyghur communities abroad

The situation for Uyghurs living abroad is far from simple. Police harassment of Uyghur immigrants is quite common, particularly through the manipulation and coercion of their family members still living in China. These threatening messages requesting personal information or pressuring dissidents abroad to remain silent. The officials rarely identify themselves and in some cases these calls or messages don’t necessarily even come from government authorities, instead coming from coerced family members and friends[13]. One interesting case was reported in August 2018 by US news publication The Daily Beast in which an unidentified Uyghur American woman was asked by her mother to send over pictures of her US license plate number, her phone number, her bank account number, and her ID card under the excuse that China was creating a new ID system for all Chinese citizens, even those living abroad[14]. A similar situation was reported by Foreign Policy when it came to Uyghurs in France who have been asked to send over home, school, and work addresses, French or Chinese IDs, and marriage certificates if they were married in France[15].

Regardless of Chinese efforts to censor Uyghur dissidents abroad, their nonconformity has only grown with the strengthening of Uyghur repression in mainland China. Important international human rights groups such as Amnesty International and the Human Rights Watch have been constantly addressing the crisis while autonomous Uyghur human rights groups, such as the Uyghur Human Rights Project, the Uyghur American Association, and the Uyghur World Congress, have developed from communities overseas. Asides from heavily protesting policies such as the internment camps and increasing surveillance in Xinjiang, these groups have had an important role when it comes to documenting the experiences of Uyghur immigrants. However, reports from both human rights group and media agencies when it comes to the crisis have been met with staunch rejection from China. One such case is the BBC being banned in China after recently reporting on Xinjiang internment camps, leading it to be accused of not being “factual and fair” by the China National Radio and Television Administration. The UK’s Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab referred to the actions taken by the state authorities as “an unacceptable curtailing of media freedom” and stated that they would only continue to damage China’s international reputation[16].

One should also think prospectively when it comes to Uyghur communities abroad. As seen in the diplomatic split between countries against China’s policies in Xinjiang and those who support them (or, at the very least, are willing to tolerate them for their political interest), a growing number of countries can excuse China’s treatment of Uyghur communities. This could eventually lead to countries permitting or perhaps even facilitating China’s attempts at coercing Uyghur immigrants, an important prospect when it comes to countries within the BRI and especially those with an important Uyghur population, such as the previously mentioned example of Kazakhstan.

REFERENCES

[1] Qian, Jingyuan. 2019. “Ethnic Conflicts and the Rise of Anti-Muslim Sentiment in Modern China.” Department of Political Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3450176.

[2] Cao, Xun, Haiyan Duan, Chuyu Liu, James A. Piazza, and Yingjie Wei. 2018. “Digging the “Ethnic Violence in China” Database: The Effects of Inter-Ethnic Inequality and Natural Resources Exploitation in Xinjiang.” The China Review (The Chinese University of Hong Kong) 18 (No. 2 SPECIAL THEMED SECTION: Frontiers and Ethnic Groups in China): 121-154. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26435650

[3] International Energy Agency. 2020. Data & Statistics - IEA. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics?country=CHINA&fuel=Energy%20consumption&indicator=TotElecCons.

[4] Yellinek, Roie, and Elizabeth Chen. 2019. “The “22 vs. 50” Diplomatic Split Between the West and China.” China Brief (The Jamestown Foundation) 19 (No. 22): 20-25. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://jamestown.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Read-the-12-31-2019-CB-Issue-in-PDF.pdf?x91188.

[5] United Nations General Assembly. 2019. “General Assembly official records, 74th session : 9th plenary meeting.” New York. Accessed October 18, 2020.

[6] Xu, Vicky Xiuzhong, Danielle Cave, James Leibold, Kelsey Munro, and Nathan Ruser. 2020. “Uyghurs for sale: ‘Re-education’, forced labour and surveillance beyond Xinjiang.” Policy Brief, International Cyber Policy Centre, Australian Strategic Policy Paper. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/uyghurs-sale

[7] Ibid.

[8] Xiao, Eva. 2020. Auditors to Stop Inspecting Factories in China’s Xinjiang Despite Forced-Labor Concerns. 21 September. Accessed December 2020, 16. https://www.wsj.com/articles/auditors-say-they-no-longer-will-inspect-labor-conditions-at-xinjiang-factories-11600697706.

[9] Kashyap, Aruna. 2020. Social Audit Reforms and the Labor Rights Ruse. 7 October. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/07/social-audit-reforms-and-labor-rights-ruse.

[10] Human Rights Watch. 2016. China: Passports Arbitrarily Recalled in Xinjiang. 21 November. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/11/22/china-passports-arbitrarily-recalled-xinjiang

[11] Human Rights Watch. 2020. China: Big Data Program Targets Xinjiang’s Muslims. 9 December. Accessed December 17, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/12/09/china-big-data-program-targets-xinjiangs-muslims.

[12] National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. 2020. How China's Xinjiang is tackling new COVID-19 outbreak. 29 October. Accessed November 14, 2020. http://en.nhc.gov.cn/2020-10/29/c_81994.htm.

[13] Uyghur Human Rights Proyect. 2019. “Repression Across Borders: The CCP’s Illegal Harassment and Coercion of Uyghur Americans.”

[14] Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany. 2018. Chinese Cops Now Spying on American Soil. 14 August. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://www.thedailybeast.com/chinese-police-are-spying-on-uighurson-american-soil.

[15] Allen-Ebrahimian. 2018. Chinese Police Are Demanding Personal Information From Uighurs in France. 2 March. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/03/02/chinese-police-are-secretly-demanding-personal-information-from-french-citizens-uighurs-xinjiang/.

[16] Reuters Staff. 2021. BBC World News barred in mainland China, radio dropped by HK public broadcaster. 11 February. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-britain-bbc/bbc-world-news-barred-from-airing-in-china-idUSKBN2AB214.

[Michael J. Seth, A Concise History of Modern Korea. From the Late Nineteenth Century to the Present (Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), Volume 2, 356 pages]

REVIEW / Jimena Villacorta

Normally, when thinking about the Korean Peninsula, we emphasize on the divided region it is now, and how the Korean War (1950-1053) had a great impact on the two independent territories we have today, North and South Korea. We forget that it once was a culturally and ethnically homogenous nation, that because of its law, couldn’t even trade with outsiders until the Treaty of Kanghwa in 1876 which marked a turning point in Korean history as it ended isolation and allowed the Japanese insertion in the territory which had great effects on its economic and political order.

Michael J. Seth narrates the fascinating history of Korea from the end of the 19th century to the present. In this edition he updates his previous work, published originally ten years before, and he presents it as a “volume 2”, because his latest years of research have produced a “volume 1”, titled A Concise History of Premodern Korea, which follows Korea's history from Antiquity through the nineteenth century.

From falling under Japanese imperialism and expansionism to its division after the Second World War, this book explores the economic, political and social issues that modern Korea has faced in the last decades. The author provides its readers a great resource for those seeking a general, yet detailed, history of this currently divided nation in eight chapters. The first two chapters focus on what happened before the Korean War and on how neighbors and other actors. Russia had great influence in the region until its defeat in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). Consequently, Korea became a colony of Japan until the Allied Forces victory during the Second World War. Japanese rule is described as harsh and detrimental for Koreans as they intended to force their own culture and system in the territory. Although, in despite of its aggressiveness, the Japanese contributed to Korea’s industrialization. Countries like China and the United States were also major players. From 1885 to 1894, China had a strong presence in the peninsula as the Chinese didn’t want other powers to take over the territory.

The rest of the book emphasizes on the war and the consequences it had, tracing the different course both countries took becoming contrasting societies with different political and economic systems. The reason for the great differences between the two Koreas is the difference in governments and influences they had after the war, a war that stopped because of a ceasefire, as to date they haven’t signed a peace treaty. Even if South Korea was under Syngman Rhee’s authoritarian and corrupt regime tight after the Korean War, it soon became democratized and the country began to quickly advance in matter of technology and human development leaving North Korea out in the open under a totalitarian dictatorship lead by Kim Jong-un. However, after the separation of the two zones, Kim II-sung was the founder of the North in 1948 and his family dynasty has ruled the country since then. During this period, South Korea has had six republics, one revolution, two coups d'état, the transition to democratic elections and nineteen presidencies. In terms of economics, they went from having a very similar GDP at the beginning of the 1970s to very different outcomes. While South Korea has progressed rapidly, becoming one of the world’s leading industrial producers, North Korea became stagnant due to its rigid state system. South Korea also has a high level of technological infrastructure. Moreover, North Korea became a nuclear power, which has been in its agenda since the division. But as he explores the technical differences of both states, the author fails to elaborate in historical debates and controversies regarding both regions, but he emphasizes on the fact that after sixty years of division, there are still no signs or reunification.

Without a doubt, it is interesting to learn about Korea’s past colonial occupation and its division, but what I believe is the most captivating is to understand how North Korea and South Korea have evolved as two independent very different states because of the uniqueness and complexity of its history, while still sharing a strong sense of nationalism. As the author says, “No modern nation ever developed a more isolated and totalitarian society than North Korea, nor such an all-embracing family cult. No society moved more swiftly from extreme poverty to prosperity and from authoritarianism to democracy than South Korea.”

Ships of the US, India and Japan in the Bay of Bengal during exercise Malabar 2017 [US Navy]

JOURNAL / Shahana Thankachan

[Document of 6 pages. Download PDF]

[Document of 6 pages. Download PDF]

INTRODUCTION

There can be no objective and singular definition of the Indo-Pacific, one can only provide an Indian definition, a Japanese definition, a US definition, an ASEAN definition, etc. This is not to say that there are no common grounds in these definitions, there are as many commonalities as there are differences, and this is what makes this topic so hot and dynamic. The geopolitical reality of the Indo-Pacific perfectly represents a great power rivalry at the systemic level and also a perfect regional security complex. In this complex matrix, this paper will seek to focus on the Indo-Pacific from the perspective of India. While the term “Indo” in the Indo-Pacific does not mean India, it does refer to the Indian Ocean and India is the most important power in the Indian Ocean. Therefore, it is very important to fully understand the Indian perspective. The paper will begin by outlining the origin of the concept and thereafter the challenges in the Indian approach to the Indo-Pacific and the future prospects.

Fortificación china en pequeñas islas disputadas [imágenes satelitales del CSIS]

JOURNAL / Fernando Delage

[Documento de 8 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

[Documento de 8 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

INTRODUCCIÓN

La idea del “Indo-Pacífico” ha irrumpido con fuerza en la discusión sobre las relaciones internacionales en Asia. Desde hace algo más de una década, distintos gobiernos han recurrido al término como marco de referencia en el que formulan su política exterior hacia la región. Si el entonces primer ministro japonés Shinzo Abe comenzó a popularizar la expresión en 2007, Australia la asumió formalmente en su Libro Blanco de Defensa de 2013; año en el que también el gobierno indio recurrió al concepto para definir el entorno regional. Como secretaria de Estado de Estados Unidos, Hillary Clinton utilizó igualmente el término en 2010, aunque fue a partir de finales de 2017, bajo la administración Trump, cuando se convirtió en la denominación oficial de la región empleada por Washington.

Aunque relacionadas entre sí, “Indo-Pacífico” tiene dos diferentes connotaciones. Representa, por un lado, una reconceptualización geográfica de Asia; un reajuste del mapa del continente como consecuencia de la creciente interacción entre ambos océanos y del ascenso simultáneo de China e India. La idea aparece vinculada, por otra parte, a una estrategia diseñada como respuesta al ascenso de China, cuyo instrumento más visible es el Diálogo Cuadrilateral de Seguridad (QUAD), un grupo informal integrado por Estados Unidos, Japón, India y Australia. Éste es el motivo de que Pekín desconfíe del término y prefiera seguir utilizando “Asia-Pacífico” para describir su vecindad, aunque sus acciones también respondan a esta nueva perspectiva: como ha señalado el analista australiano Rory Medcalf, la Ruta Marítima de la Seda no es sino “el Indo-Pacífico con características chinas”.

El protagonismo de las grandes potencias en el origen y uso de la expresión parece haber relegado el papel de la ASEAN y sus Estados miembros. Pese a su menor peso económico y militar, no carecen sin embargo de relevancia. Además de estar ubicada en la intersección de los dos océanos —el sureste asiático constituye, de hecho, el centro del Indo-Pacífico—, las disputas en torno al mar de China Meridional sitúan a la subregión en medio de la rivalidad entre China y Estados Unidos. Mientras la primera extiende su influencia a través de su diplomacia económica a la vez que inquieta a los Estados vecinos por sus reclamaciones marítimas, la administración Trump optó por oponerse de manera directa a ese mayor poder económico y militar chino. La ASEAN no quiere verse atrapada en la confrontación entre Washington y Pekín, ni tampoco marginada en la reconfiguración en curso de la estructura regional. Sus Estados miembros quieren beneficiarse de las oportunidades para su desarrollo que les proporciona China, pero también quieren contar con un apoyo externo que actúe como contrapeso estratégico de la República Popular. Aunque estas circunstancias explican sus reservas sobre un concepto que pone en riesgo su cohesión e identidad como organización, la ASEAN terminó adoptando en 2019 su propia “Perspectiva sobre el Indo-Pacífico”, un documento oficial que revela sus esfuerzos por mantener su independencia.

Mapa del área de competencia del Comando para el Indo-Pacífico del Pentágono estadounidense [USINDOPACOM]

JOURNAL / Juan Luis López Aranguren

[Documento de 6 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

[Documento de 6 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

INTRODUCCIÓN

El cambio tectónico internacional que se está produciendo con la cristalización del Indo-Pacífico como uno de los principales ejes globales no es algo que pasase desapercibido a los internacionalistas de los últimos 150 años. Ya a finales del siglo XIX, el historiador y estratega naval Alfred Thayer Mahan predijo que “quien domine el Océano Índico dominará Asia y el destino del mundo se decidirá en sus aguas”. Tiempo después, en 1924, Karl Haushofer predijo la llegada de lo que llamó “la Era del Pacífico”. Posteriormente, Henry Kissinger afirmó que uno de los cambios más drásticos a nivel global que se producirían en este siglo sería el desplazamiento del centro de gravedad de las relaciones internacionales del Atlántico al Índico y Pacífico. Y fue en los ochenta, durante la mítica reunión entre Deng Xiaoping y el primer ministro indio Rajiv Gandhi, cuando se produjo la declaración por parte de Deng indicando que sólo cuando China, India y otras naciones vecinas colaboren se podría hablar de un “siglo de Asia-Pacífico”.

En cualquier caso, la experiencia histórica indica que la unidad y la colaboración entre diferentes estructuras sociales (sean estas naciones, ideologías o civilizaciones) pueden coexistir con relaciones competitivas entre ellas provocando que el escenario donde interactúan y rivalizan se convierta en uno de los ejes geopolíticos del planeta. El Mediterráneo fue el punto de unión, comunicación y comercio de las culturas clásicas a las que regaban sus aguas durante milenios, pero también un espacio de competición diplomática y lucha por recursos, influencia y expansión de colonias, tal y como describió Tucídides en su Guerra del Peloponeso. De la misma forma, desde el siglo XV, el Atlántico también fue el campo de competición estratégica en la proyección progresiva de las ballenas o potencias marítimas europeas hacia América y África occidental, solapándose las dimensiones política, económica, religiosa y cultural. Y el siglo XVIII fue testigo del intenso conflicto desatado en el océano Índico entre Francia, Reino Unido y el Imperio maratha indio por el control de sus aguas y sus costas.

En última instancia, los mares y los océanos son el vector que permite a las potencias terrestres expandirse y proyectar su poder fuerte o blando más allá de las limitaciones de su ámbito territorial. El mar se convierte así en el ámbito donde el árbol de posibilidades de las naciones se maximiza. Ya lo explicó Ian Morris destacando que la razón por la que Europa se había convertido a partir del siglo XV en un poder global, expandiendo su civilización por todo el planeta, era precisamente que Europa era una península de penínsulas, y esto ofrecía un fácil acceso al mar a cualquier idea, producto, fuerza militar y revolución que se quisiera exportar e importar. El mar ha sido, por lo tanto, un acelerador de la evolución social en aquellas civilizaciones que contaban con la ventaja estratégica de un fácil acceso al mismo. Por ello, el planteamiento de la futura evolución de las dinámicas globales desde una perspectiva marítima en lugar de terrestre puede resultar más práctico a la hora de definir los futuros escenarios posibles. Esto nos lleva a la conclusión de que quizá resulta más adecuado hablar de una Era del Indo-Pacífico antes que de un siglo terrestre asiático, ya que estos océanos se asemejan a un lienzo donde los poderes antiguos y nuevos, regionales y globales, colectivistas e individualistas, se disputan la proyección de sus intereses, sus esferas de influencias y sus identidades, hasta lograr un alcance global.

Xi y Trump durante la única visita del presidente estadounidense a China, en 2017 [Casa Blanca]

JOURNAL / Florentino Portero

[Documento de 10 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

[Documento de 10 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

INTRODUCCIÓN

Occidente admiró a Deng Xiaoping y comprendió que China, el imperio milenario, comenzaba una nueva etapa que habría que seguir con detenimiento, pues fuera cual fuera el camino finalmente elegido la China resultante determinaría la evolución del planeta en su conjunto.

El Imperio del Centro no había sabido o querido entender la dimensión histórica de la I Revolución Industrial y con ello se adentró en un callejón sin más salida que la humillación internacional y el fin de su régimen político. Japón vivió circunstancias semejantes, pero supo reaccionar. Gracias a la Revolución Meiji cambió su estrategia y trató de comprender y adaptarse a las nuevas circunstancias. China acabaría sufriendo la invasión japonesa de Manchuria y la imposición de condiciones humillantes por parte de las potencias occidentales. Finalmente, el Imperio fue derribado, dando paso a una guerra civil que se complicaría con la II Guerra Mundial y el intento japonés de imponerse como potencia de referencia en Extremo Oriente. En aquel complejo proceso de descomposición y reconstrucción de una cultura política profundamente enraizada, China perdió la oportunidad de entender y sumarse a la II Revolución Industrial.

El triunfo del Partido Comunista chino en la guerra civil puso fin al proceso de descomposición y dio paso a un nuevo período de su historia. De nuevo se imponía en Beijing un poder fuerte, en este caso totalitario, que reconstruyó y dotó de gran energía al estado. Los nuevos gobernantes, con Mao Zedong a la cabeza, trataron de imponer una cultura ajena, trasformando muchos de los elementos característicos del antiguo Imperio. Fue aquel un gran intento de ingeniería social, que abocó a una generalizada pérdida de libertad y pobreza, mientras la corrupción empapaba las distintas capas del partido. China había vuelto, estaba dotada de un estado fuerte y de un liderazgo cohesionado y dispuesto a asumir grandes responsabilidades. Sin embargo, la ideología se impuso al realismo y China perdió la III Revolución Industrial, privando a su pueblo de bienestar y a su economía de un modelo de desarrollo viable.

Mapa de la visión japonesa de Pacífico Libre y Abierto [MoFA]

JOURNAL / Carmen Tirado Robles

[Documento de 8 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

[Documento de 8 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

INTRODUCCIÓN

Se dice que el concepto de Indo-Pacífico libre y abierto (FOIP) se remonta al artículo del oficial naval indio Capitán Gurpreet Khurana, quien escribió por primera vez sobre este concepto geopolítico a principios de 2007, en un documento titulado “Security of Sea Lines: Prospects for India-Japan Cooperation”. En aquel entonces, el Indo-Pacífico libre y abierto era principalmente un concepto geográfico que describía el espacio marítimo que se extendía desde los litorales de África oriental y Asia occidental, a través del Océano Índico y el Océano Pacífico occidental hasta las costas de Asia oriental. En la misma época el primer ministro japonés Shinzo Abe presentaba su plan de política exterior cimentada en valores democráticos a partir de la cual proponía “I will engage in strategic dialogues at the leader’s level with countries that share fundamental values such as Australia and India, with a view to widening the circle of free societies in Asia as well as in the world”, lo que unido a la consolidación de las relaciones con Estados Unidos (“The times demanded that Japan shift to proactive diplomacy based on new thinking. I will demonstrate the ‘Japan-U.S. Alliance for Asia and the World’ even further, and to promote diplomacy that will actively contribute to stalwart solidarity in Asia”), crea el concepto de Cuadrilátero o Quad, en contraposición con una visión sino-céntrica de Asia.

La idea del Quad se une al FOIP cuando Abe, en agosto de 2007, en su discurso ante el Parlamento de India, se basó en la “Confluencia de los océanos Índico y Pacífico” y “el acoplamiento dinámico como mares de libertad y prosperidad” de la región geográfica más grande de Asia y más tarde, ya en su segundo mandato, presentó en la VI Conferencia de Tokio sobre Desarrollo de África, que tuvo lugar en Nairobi (Kenia) el 27 de agosto de 2016 (TICAD VI), el nuevo marco geopolítico del Indo-Pacífico.

[Alyssa Ayres, Our Time Has Come. How India Is Making Its Place in the World (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2020) 360 pgs.]

RESEÑA / Alejandro Puigrefagut