Breadcrumb

Blogs

![Artistic image of a Pakistani Rupee [Pixabay] Artistic image of a Pakistani Rupee [Pixabay]](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-country-risk-report-blog.jpg)

▲ Artistic image of a Pakistani Rupee [Pixabay]

COUNTRY RISK REPORT / M. J. Moya, I. Maspons, A. V. Acosta

April 2020

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The government of Prime Minister (PM), Imran Khan, was slowly moving towards economic, social, and political improvements, but all these efforts might be hampered by the recent outbreak of the COVID-19 virus since the government must temporarily shift its focus and resources to keeping its population safe. Additionally, high logistical, legal, and security challenges still generate an uncompetitive operating environment and thus, an unattractive market for foreign investment in Pakistan.

Firstly, in relation to the country’s economic outlook, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was expected to gradually recover around 5% in the upcoming years. However, according to latest estimates, this growth will suffer a negative impact and fall to around 2%, straining the country’s most recent recorded improvements. On the other hand, in the medium to long-term, Pakistan will benefit from the success of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which is a strategic economic project aiming to improve infrastructure capacity in the country. Pakistan is also facing an energy crisis along with a growing demand from a booming population that hinder a proper economic progress.

Secondly, Pakistan’s political future will be shaped by Khan’s ability to transform his short-term policies into long-term strategies. However, in order to achieve this, the government must tackle the root causes of political instability in Pakistan, such as long-lasting corruption, the constant military influence in decision-making processes, the historical debate among secularism and Islamism, and the new challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, PM Khan’s progressive reforms could represent the beginning towards a “Naya Pakistan” (“New Pakistan”).

Thirdly, Pakistan’s social stability is contextualized within a high risk of terrorist attacks due to its internal security gaps. The ethnic dilemma among the provinces along with the government’s violent oppression of insurgencies will continue to impede development and social cohesion within the country. This will further aggravate in light of a current shortage of resources and the impacts of climate change.

In addition, in terms of Pakistan’s security outlook, the country is expected to tackle terrorist financing and money laundering networks in order to avoid being blacklisted by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). Nonetheless, due to a porous border with Afghanistan, Pakistan faces drug trafficking challenges that further destabilize national security. Finally, the turbulent Indo-Pakistani relation is the most significant conflict for the South Asian country. The disputed region of Jammu and Kashmir, a possible nuclear confrontation, and the increase of nationalist movements along the Punjab region, hamper regional and international peace.

![Ejercicios navales de comandos de la Guardia Revolucionaria en el Estrecho de Ormuz en 2015 [Wikipedia] Ejercicios navales de comandos de la Guardia Revolucionaria en el Estrecho de Ormuz en 2015 [Wikipedia]](/documents/10174/16849987/iran-nueva-guerra-fria-blog.jpg)

▲ Ejercicios navales de comandos de la Guardia Revolucionaria en el Estrecho de Ormuz en 2015 [Wikipedia]

ENSAYO / Ana Salas Cuevas

La República Islámica de Irán, también conocida como Persia, es un país con gran importancia en la geopolítica. Es una potencia regional no solo por su localización estratégica, sino también por sus grandes recursos de hidrocarburos, que hacen de Irán el cuarto país en reservas probadas de petróleo y el primero en reservas de gas[1].

Así hablamos de uno de los países más importantes del mundo por tres motivos fundamentales. El primero, mencionado anteriormente: sus inmensas reservas petrolíferas y de gas. En segundo lugar, porque Irán controla el estrecho de Ormuz, que es llave de entrada y salida del Golfo Pérsico y por el que pasan la mayor parte de las exportaciones de hidrocarburos de Irán, Arabia Saudí, Irak, Emiratos Árabes, Kuwait, Catar y Bahréin[2]. Por último, por el programa nuclear en el que ha invertido tantos años[3].

La república iraní se basa en los principios del Islam chií, aunque hay una gran diversidad étnica en su sociedad. Por ello, es indispensable tener en cuenta la gran “fuerza del nacionalismo iraní” para comprender su política. Apelando a la posición dominante sobre otros países, el movimiento nacionalista iraní pretende influir en la opinión pública. El nacionalismo se ha ido asentando desde hace más de 120 años, desde que el Boicot de Tabaco de 1891[4] supuso una respuesta directa a la intervención y presión exterior, y hoy pretende lograr la hegemonía en la región. La política exterior e interior de Irán son una clara expresión de este movimiento[5].

Por agente interpuesto (Proxy armies)

La guerra subsidiaria (en inglés, war by proxy) es un modelo de guerra en el cual un país hace uso de terceros para combatir o influenciar en un determinado territorio, en lugar de enfrentarse directamente. Como señala David Daoud, en el Líbano, Irak, Yemen y Siria, “Teherán ha perfeccionado el arte de conquistar gradualmente un país sin reemplazar su bandera”[6]. En esa tarea participa directamente la Guardia Revolucionaria Islámica de Irán (GRI), formando o favoreciendo militarmente a las fuerzas de otros países.

La GRI nació con la Revolución Islámica liderada por el ayatolá Ruhollah Jomeini, con el fin de mantener los logros del movimiento[7]. Se trata de uno de los principales actores políticos y sociales del país. Posee gran capacidad para influir en los debates y decisiones de la política nacional. Es, además, propietaria de numerosas empresas dentro del país, lo que le garantiza una fuente de financiación propia y refuerza su carácter de poder interno. Constituye un cuerpo independiente de las fuerzas armadas, y el nombramiento de sus altos cargos depende directamente del Líder de la Revolución. Entre sus objetivos está la lucha contra el imperialismo, y expresamente se compromete a intentar rescatar Jerusalén para devolverla a los palestinos[8]. Su importancia es crucial para el régimen, y cualquier ataque a estos cuerpos representa una amenaza directa al gobierno iraní[9].

La relación de Irán con los países musulmanes de su entorno se encuentra marcada por dos hechos principales: por un lado, su condición chiita; por otro, la preeminencia que logró tener en el pasado en la región[10]. Gracias a que su acción exterior se encuentra apoyada en la Guardia Revolucionaria Islámica, Irán ha conseguido establecer grandes vínculos con grupos políticos y religiosos por todo Oriente Medio. A partir de ahí, Irán aprovecha distintos recursos para afianzar su influencia en los distintos países. En primer lugar, haciendo uso de herramientas de poder blando o soft power. Así, entre otras acciones, ha participado en la reconstrucción de mezquitas y escuelas en países como el Líbano o Irak[11]. En Yemen ha proporcionado ayudas logísticas y económicas al movimiento hutí. En 2006, se implicó en la reconstrucción del sur de Beirut.

No obstante, los métodos utilizados por estas fuerzas alcanzan otros extremos, pasando a mecanismos más intrusivos (hard power). Por ejemplo, tras la invasión israelí de 1982 en el Líbano, Irán ha ido estableciendo allí a lo largo de tres décadas un punto de apoyo, con Hezbolá como proxy, aprovechando las quejas sobre la privación de derechos de la comunidad chiita. Esta línea de acción ha permitido a Teherán promover su Revolución Islámica en el extranjero[12].

En Irak la GRI buscó la desestabilización interna de Irak, apoyando facciones chiitas como la organización Badr, durante la guerra irano-iraquí de la década de 1980. Por otro lado, Irán involucró a la GRI en el levantamiento de Saddam Hussein a principios de la década de 1990. A través de este tipo de influencias y encarnando el paradigma de proxy army, Irán ha ido estableciendo influencias muy directas sobre estos lugares. Incluso en Siria, este cuerpo de élite iraní tiene una gran influencia, apoyando al gobierno de Al Assad y las milicias chiitas que combaten junto a él.

Por su parte, Arabia Saudí acusa a Iran y su Guardia de proveer armas en Yemen a los hutíes (movimiento que defiende a la minoría chiita), generando una importante escalada de tensión entre ambos países[13].

La GRI se consolida, así, como uno de los factores más importantes en el panorama de Oriente Medio, impulsando la lucha entre dos bandos que quedan contrapuestos. No obstante, no es el único. De esta manera, encontramos un escenario de “guerra fría”, que acaba trascendiendo y convirtiéndose en foco internacional. Por un lado, Irán, apoyado por potencias como Rusia o China. Por el otro, Arabia Saudí, de la mano de EEUU. Esta contienda se desarrolla, en gran medida, de una manera no convencional, a través de proxy armies como Hezbolá y las milicias chiitas en Irak, en Siria o en Yemen[14].

Causas de una confrontación

Las tensiones entre Arabia Saudí e Irán se han extendido a todo Oriente Medio (y más allá), creando en este territorio dos bandos bien determinados, ambos con pretensión de adjudicarse la hegemonía en la zona.

Para interpretar este escenario y comprender mejor su oposición es importante, en primer lugar, distinguir dos corrientes ideológicas contrapuestas: el chiismo y el sunismo (wahabismo). El wahabismo es una tendencia religiosa musulmana de extrema derecha, de la rama del sunismo, que hoy en día es la religión mayoritaria en Arabia Saudí. El chiismo, como previamente se ha mencionado, es la corriente en la que se basa la República de Irán. No obstante, como veremos, la pugna que se desarrolla entre Irán y Arabia Saudí es política, no religiosa; está más basada en la ambición de poder, que en la religión.

En segundo lugar, encontramos en el control del tráfico del petróleo otra causa de esta rivalidad. Para entender este motivo, conviene tener en cuenta la posición estratégica que juegan los países de Oriente Medio en el mapa global al acoger las mayores reservas de hidrocarburos del mundo. Un gran número de luchas contemporáneas se deben, en efecto, a la intromisión de las grandes potencias en la región, intentando tener un papel sobre estos territorios. Así, por ejemplo, el acuerdo de Sykes-Picot[15] de 1916 para el reparto de influencias europeas sigue condicionando acontecimientos actuales. Tanto Arabia Saudí como Irán, como venimos diciendo, poseen un protagonismo especial en estos enfrentamientos, por las razones descritas.

Bajo estas consideraciones, es importante señalar, en tercer lugar, la implicación en dichas tensiones de potencias exteriores como Estados Unidos.

Los efectos de las primaveras árabes han debilitado a muchos países de la zona. No así a Arabia Saudí e Irán, que han buscado en las últimas décadas su consolidación como potencias regionales, en gran medida gracias al respaldo que les otorga su producción y sus grandes reservas de petróleo. Las diferencias entre ambos países se ven reflejadas en la manera en la que intentan configurar la región y en los distintos intereses que pretenden lograr. Además de las diferencias étnicas entre Irán (persas) y Arabia Saudí (árabes), su alineamiento en el panorama internacional también es opuesto. El wahabismo se presenta como antinorteamericano, pero el gobierno saudí es consciente de la necesidad que tiene del apoyo de EEUU, y ambos países mantienen una conveniencia recíproca, con el petróleo como base. No sucede lo mismo con Irán.

Irán y EEUU fueron estrechos aliados hasta 1979. La Revolución Islámica lo cambió todo y desde entonces, con la crisis de los rehenes de la embajada estadounidense en Teherán como momento inicial especialmente dramático, las tensiones entre los dos países han sido frecuentes. La confrontación diplomática ha vuelto a ser aguda con la decisión del presidente Donald Trump de retirada del Plan de Acción Integral Conjunto (PAIC), firmado en 2015 para la no proliferación nuclear de Irán, con la consiguiente reanudación de las sanciones económicas hacía este país. Además, en abril de 2019 Estados Unidos situó a la Guardia Revolucionaria en su lista de organizaciones terroristas[16], responsabilizando a Irán de financiar y promover el terrorismo como una herramienta de gobierno[17].

Por un lado, pues, está el bando de los saudís, apoyados por EEUU y, dentro de la región, por Emiratos Árabes Unidos, Kuwait, Baréin e Israel. Por el otro lado, Irán y sus aliados de Palestina, Líbano (parte pro-chiita) y recientemente Qatar, lista a la que podría añadirse Siria e Irak (milicias chiitas). Las tensiones aumentaron tras la muerte de Qasem Soleimani en enero de 2020. En este último bando podríamos destacar el apoyo internacional de China o Rusia, pero poco a poco podemos observar un alejamiento de las relaciones entre Irán y Rusia.

Al hablar de la lucha por la hegemonía del control del tráfico del petróleo, es imprescindible mencionar el Estrecho de Ormuz, el punto geográfico crucial de esta contienda, donde se ven enfrentadas ambas potencias directamente. Este estrecho es una zona estratégica situada entre el Golfo Pérsico y el de Omán. Por ahí pasa un 40% del petróleo mundial[18]. El control de estas aguas es, evidentemente, decisivo en el enfrentamiento entre Arabia Saudí e Irán; así como para cualquiera de los miembros de la Organización de Países Exportadores de Petróleo de Oriente Medio (OPEP) en la región: Irán, Arabia Saudí, Irak, Emiratos Árabes y Kuwait.

Uno de los objetivos de las sanciones económicas impuestas por Washington a Irán es reducir sus exportaciones para favorecer a Arabia Saudí, su mayor aliado regional. A estos efectos, la Quinta Flota estadounidense, con sede en Baréin, tiene la tarea de proteger la navegación comercial en esta área.

El Estrecho de Ormuz “es la válvula de escape que utiliza Irán para aliviar la presión que se ejerce desde fuera del Golfo” [19]. Desde aquí, Irán intenta reaccionar ante las sanciones económicas impuestas por EEUU y otras potencias; es lo que le otorga una mayor voz en el panorama internacional, al tener capacidad de bloquear el estratégico paso. Recientemente se han dado ataques a petroleros de Arabia Saudí y otros países[20], algo que provoca una gran desestabilización tanto económica como militar en cada nuevo episodio[21].

En definitiva, la competencia entre Irán y Arabia Saudí tiene un efecto no solo regional sino que afecta globalmente. Los conflictos que pudieran desatarse en esta área recuerdan, cada vez más, a una ya conocida Guerra Fría, tanto por los métodos en el frente de batalla (y la incidencia de las proxy armies en este frente), como por la atención que requiere para el resto del mundo, que depende de este resultado, quizá, bastante más de lo que es consciente.

Conclusiones

Desde hace varios años se ha ido consolidando un enfrentamiento regional que implica también a las grandes potencias. Esta lucha trasciende las fronteras de Oriente Medio, análogamente a la situación desencadenada durante la Guerra Fría. Sus principales agentes son las proxy armies, que impulsan luchas a través de agentes no estatales y con métodos de guerra no convencionales, desestabilizando constantemente las relaciones entre los Estados, así como dentro de los propios Estados.

Para evitar la lucha en Ormuz, países como Arabia Saudí y los Emiratos Árabes Unidos han intentado transportar el petróleo por otras vías, por ejemplo, mediante la construcción de oleoductos. Este grifo lo tiene Siria, país por el que las conducciones deben pasar para llegar a Europa). Al fin y al cabo, la guerra de Siria se puede ver desde muchas perspectivas, pero no hay duda de que uno de los motivos de la intromisión de potencias extrarregionales es el interés económico que conlleva la costa siria.

Desde 2015 hasta ahora se libra la silenciada guerra civil de Yemen. En ella están en juego asuntos estratégicos como el control del Estrecho de Mandeb. Detrás de esta terrible guerra contra los hutíes (proxies), hay un latente miedo a que estos se hagan con el control de acceso al Mar Rojo. En este mar y cerca del estrecho se encuentra Djibouti, donde las grandes potencias han instalado bases militares para un mejor control sobre la zona.

La potencia más perjudicada es Irán, que ve su economía debilitada por las constantes sanciones económicas. La situación afecta a una población oprimida tanto por el propio gobierno como por la presión internacional. El propio gobierno acaba desinformando a la sociedad, provocando una gran desconfianza hacia las autoridades. Esto genera una creciente inestabilidad política, que se manifiesta en frecuentes protestas.

El régimen ha publicitado esas manifestaciones como protestas por las actuaciones de EEUU, como por ejemplo a raíz del asesinato del general Soleimani, sin mencionar que muchas de estas revueltas se deben al gran descontento de la población civil por las graves medidas tomadas por el ayatolá Jamenei, más centrado en procurar la hegemonía en la zona que en resolver los problemas internos.

Así, muchas veces es difícil darse cuenta de implicación de estos enfrentamientos para la mayoría del mundo. En efecto, la utilización de proxy armies no debe distraernos del hecho de la verdadera involucración de las principales potencias de Occidente y de Oriente (al verdadero modo de una Guerra Fría). Tampoco los motivos que se alegan para mantener estos frentes abiertos deben distraernos de la verdadera incidencia de lo que está en juego realmente: ni más ni menos que la economía global.

[1] El nuevo mapa de los gigantes globales del petróleo y el gas, David Page, Expansión.com, el 26 de junio de 2013. Disponible en

[2] Los cuatro puntos clave por los que viaja el petróleo: El Estrecho de Ormuz, el “arma” de Irán, 30 de julio de 2018. Disponible en

[3] En noviembre de 2013 firmaban China, Rusia, Francia, Reino Unido y Estados Unidos (P5) e Irán el Plan de Acción Conjunto (PAC). Se trató de un acuerdo inicial sobre el programa nuclear de Irán sobre el cual se realizaron varias negociaciones que concluyeron con un pacto final, el Plan de Acción Integral Conjunto (PAIC), firmado en 2015, al que se adhirió la Unión Europea.

[4] El Boicot de Tabaco fue el primer movimiento en contra de una actuación concreta del Estado, no se dio una revolución en el sentido estricto de la palabra, pero en él se arraigó un fuerte nacionalismo. Se dio debido a la ley del monopolio del tabaco concedida a los británicos en 1890. Más información en: “El veto al tabaco”, Joaquín Rodríguez Vargas, Profesor de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

[5] Cuaderno de estrategia 137, Ministerio de Defensa: Irán, potencia emergente en Oriente Medio. Implicaciones en la estabilidad del Mediterráneo. Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos, julio de 2007. Disponible en

[6] Meet the Proxies: How Iran Spreads Its Empire through Terrorist Militias,The Tower Magazine, March 2015. Disponible en

[7] El artículo 150 de la Constitución de la República Islámica de Irán lo dice expresamente.

[8] Tensiones entre Irán y Estados Unidos: causas y estrategias, Kamran Vahed, Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos, noviembre 2019. Disponible en, pág. 5.

[9] Una de las seis secciones de la GRI es la Fuerza “Quds” (cuyo comandante era Qasem Soleimani), especializada en guerra convencional y operaciones de inteligencia militar. También responsable de llevar a cabo intervenciones extraterritoriales.

[10] Irán, Ficha país. Oficina de Información Diplomática, España. Disponible en

[11] Tensiones entre Irán y Estados Unidos: causas y estrategias, Kamran Vahed, Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos, noviembre 2019. Disponible en

[12] Hezbollah Watch, Iran’s Proxy War in Lebanon. November 2018. Disponible en

[13] Yemen: la batalla entre Arabia Sudí e Irán por la influencia en la región, Kim Amor, 2019, El Periódico. Disponible en

[14] Irán contra Arabia Saudí, ¿una guerra inminente?, Juan José Sánchez Arreseigor, IEEE, 2016. Disponible en

[15] El acuerdo de Sykes-Picot fue un pacto secreto entre Gran Bretaña y Francia durante la Primera Guerra Mundial (1916) en el que, con el consentimiento de Rusia (aún presoviética), ambas potencias se repartieron las zonas conquistadas del Imperio Otomano tras la Gran Guerra.

[16] Foreign Terrorist Organizations, Boureau of Counterterrorism. Disponible en

[17] Statement from the President on the Designation of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, Foreign Policy, april of 2019. Disponible en

[18] El estrecho de Ormuz, la principal arteria del petróleo mundial, Euronews (datos contrastados con Vortexa), 14 de junio de 2019. Disponible en

[19] “Máxima presión” en el Estrecho de Ormuz, Félix Arteaga, Real Instituto el Cano, 2019. Disponible en

[20] Estrecho de Ormuz: qué se sabe de las nuevas explosiones en buques petroleros que aumentan la tensión entre Estados Unidos e Irán, BBC News Mundo, 14 junio 2019. Disponible en

[21] Arabia Saudí denuncia el sabotaje de dos petroleros en aguas de Emiratos Árabes, Ángeles Espinosa, 14 de mayo de 2019, El País. Disponible en

![Logo of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence organization. It depicts Pakistan's national animal, Markhor, eating a snake [Wikipedia] Logo of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence organization. It depicts Pakistan's national animal, Markhor, eating a snake [Wikipedia]](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-isi-blog.jpg)

▲ Logo of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence organization. It depicts Pakistan's national animal, Markhor, eating a snake [Wikipedia]

ESSAY / Manuel Lamela

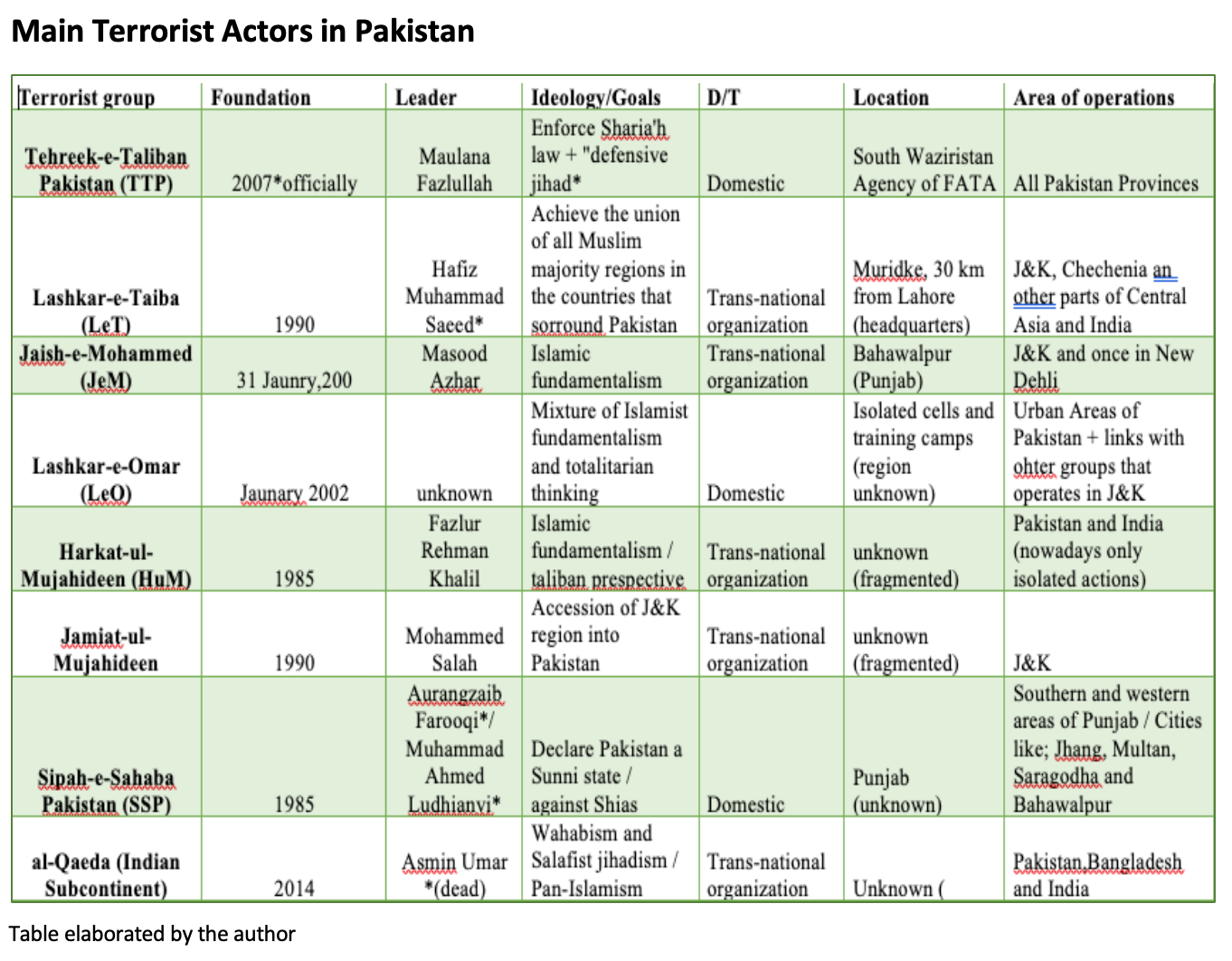

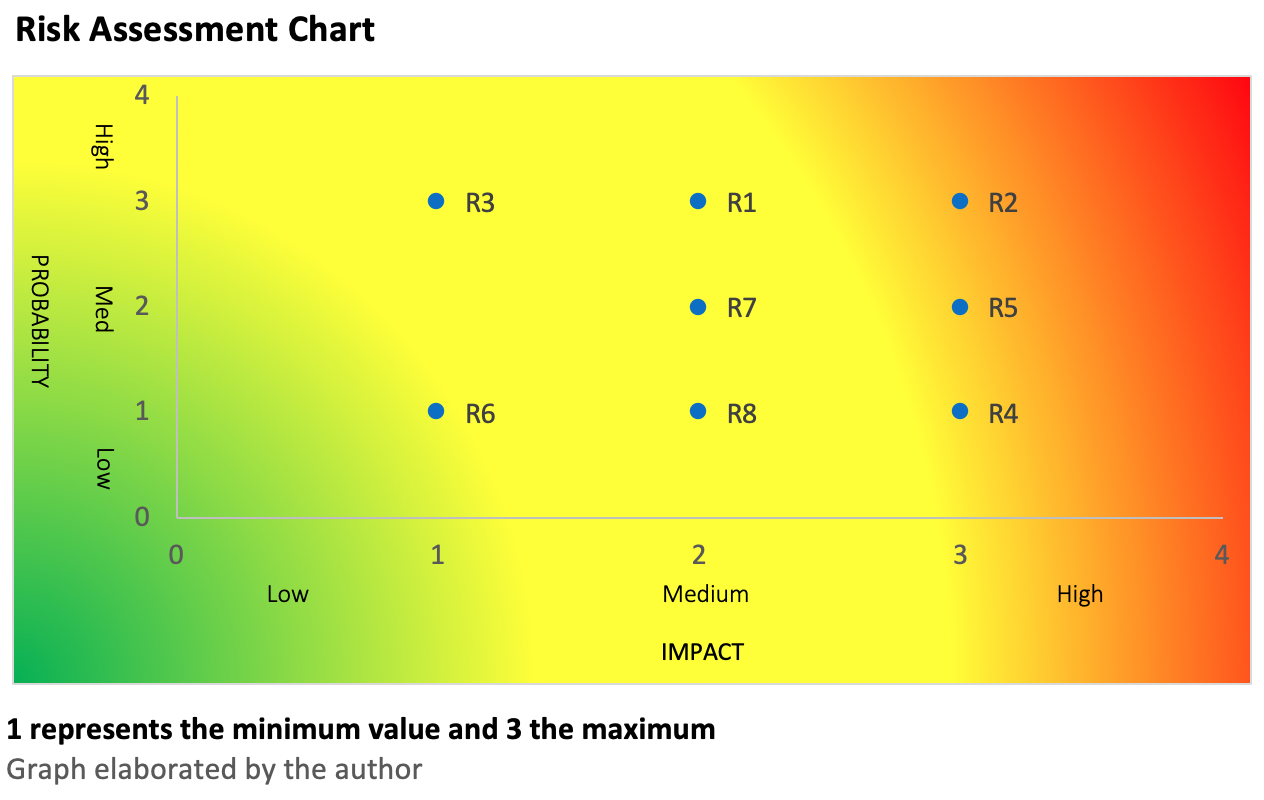

Jihadism continues to be one of the main threats Pakistan faces. Its impact on Pakistani society at the political, economic and social levels is evident, it continues to be the source of greatest uncertainty, which acts as a barrier to any company that is interested in investing in the Asian country. Although the situation concerning terrorist attacks on national soil has improved, jihadism is an endemic problem in the region and medium-term prospects are not positive. The atmosphere of extreme volatility and insistence that is breathed does not help in generating confidence. If we add to this the general idea that Pakistan's institutions are not very strong due to their close links with certain radical groups, the result is a not very optimistic scenario. In this essay, we will deal with the current situation of jihadism in Pakistan, offering a multidisciplinary approach that helps to situate itself in the complicated reality that the country is experiencing.

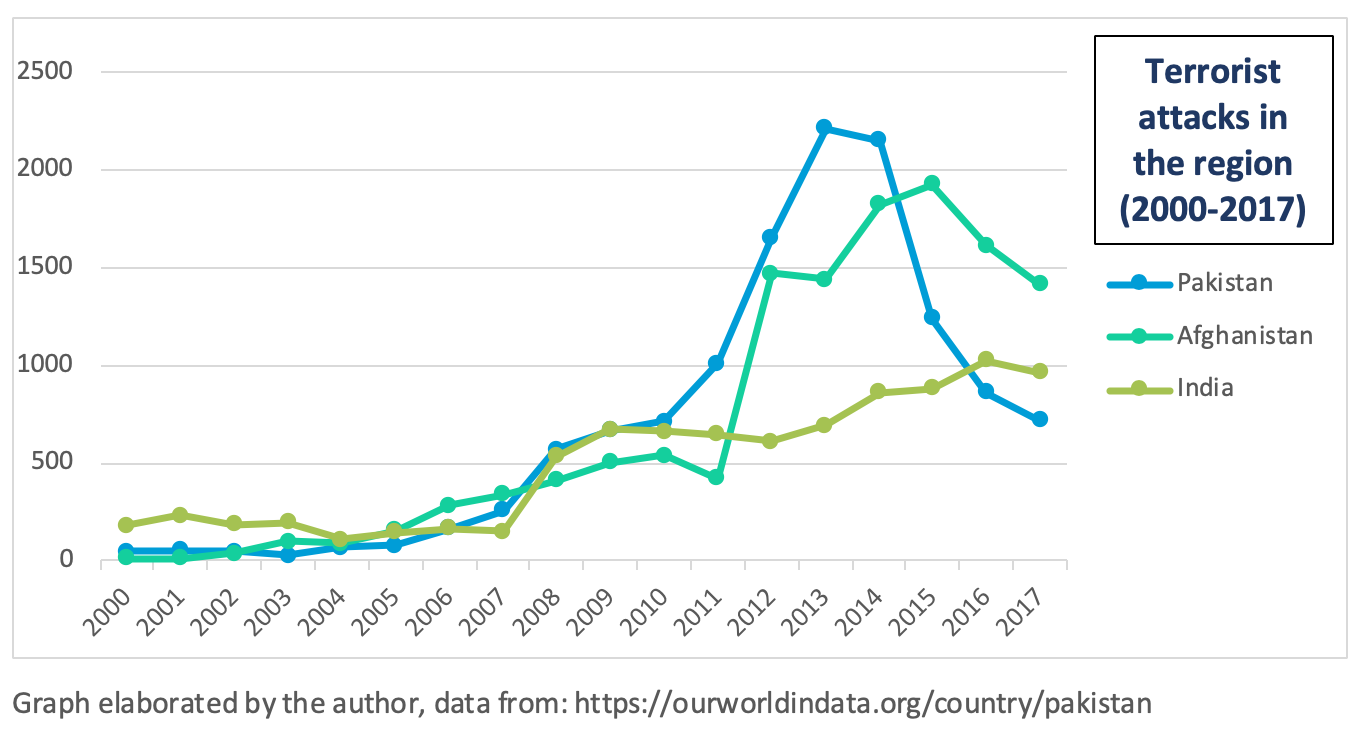

1. Jihadism in the region, a risk assessment

Through this graph, we will analyze the probability and impact of various risk factors concerning jihadist activity in the region. All factors refer to hypothetical situations that may develop in the short or medium term. The increase in jihadist activity in the region will depend on how many of these predictions are fulfilled.

Risk Factors:

R1: US-Taliban treaty fails, creating more instability in the region. If the United States is not able to make a proper exit from Afghanistan, we may find ourselves in a similar situation to that experienced during the 1990s. Such scenario will once again plunge the region into a fierce civil war between government forces and Taliban groups. The proposed scenario becomes increasingly plausible if we look at the recent American actions regarding foreign policy.

R2: Pakistan two-head strategy facing terrorism collapse. Pakistan’s strategy in dealing with jihadism is extremely risky, it’s collapse would lead to a schism in the way the Asian state deals with its most immediate challenges. The chances of this strategy failing in the medium term are considerably high due to its structure, which makes it unsustainable over the time.

R3: Violations of the LoC by the two sides in the conflict. Given the frequency with which these events occur, their impact is residual, but it must be taken into account that it in an environment of high tension and other factors, continuous violations of the LoC may be the spark that leads to an increase in terrorist attacks in the region.

R4: Agreement between the afghan Taliban and the government. Despite the recent agreement between Ashraf Ghani and Abdullah Albduallah, it seems unlikely that he will be able to reach a lasting settlement with the Taliban, given the latter's pretensions. If it is true that if it happens, the agreement will have a great impact that will even transcend Afghan borders.

R5: Afghan Taliban make a coup d’état to the afghan government. In relation to the previous point, despite the pact between the government and the opposition, it seems likely that instability will continue to exist in the country, so a coup attempt by the Taliban seems more likely than a peaceful solution in the medium or long term

R6: U.S. Democrat party wins the 2020 elections. Broadly speaking, both Republican and Democratic parties are betting on focusing their efforts on containing the growth of their great rival, China.

R7: U.S. withdraw its troops from Afghanistan regarding the result of the peace process. This is closely related to the previous point as it responds to a basic geopolitical issue.

R8: New agreement between India and Pakistan regarding the LoC. If produced, this would bring both states closer together and help reduce jihadist attacks in the Kashmir region. However, if we look at recent events, such a possibility seems distant at present.

2. The ties between the ISI and the Taliban and other radical groups

Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) has been accused on many occasions of being closely linked to various radical groups; for example, they have recently been involved with the radicalization of the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh[1]. Although Islamabad continues strongly denying such accusations, reality shows us that cooperation between the ISI and various terrorist organizations has been fundamental to their proliferation and settlement both on national territory and in the neighboring states of India and Afghanistan. The West has not been able to fully understand the nature of this relationship and its link to terrorism. The various complaints to the ISI have been loaded with different arguments of different kinds, lacking in unity and coherence. Unlike popular opinion, this analysis will point to the confused and undefined Pakistani nationalism as the main cause of this close relationship.

The Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence, together with the Intelligence Bureau and the Military Intelligence, constitute the intelligence services of the Pakistani State, the most important of which is the ISI. ISI can be described as the intellectual core and center of gravity of the army. Its broad functions are the protection of Pakistan's national security and the promotion and defense of Pakistan's interests abroad. Despite the image created around the ISI, in general terms its activities and functions are based on the same "values" as other intelligence agencies such as the MI6, the CIA, etc. They all operate under the common ideal of protecting national interests, the essential foundation of intelligence centers without which they are worthless. We must rationalize their actions on the ground, move away from inquisitive accusations and try to observe what are the ideals that move the group, their connection with the government of Islamabad and the Pakistani society in general.

2.1. The Afghan Taliban

To understand the idiosyncrasy of the ISI we must go back to the war in Afghanistan[2], it is from this moment that the center begins to build an image of itself, independent of the rest of the armed forces. From the ISI we can see the victory of the Mujahideen on Afghan territory as their own, a great achievement that shapes their thinking and vision. But this understanding does not emerge in isolation and independently, as most Pakistani society views the Afghan Taliban as legitimate warriors and defenders of an honorable cause[3]. The Mujahideen victory over the USSR was a real turning point in Pakistani history, the foundation of modern Pakistani nationalism begins from this point. The year 1989 gave rise to a social catharsis from which the ISI was not excluded.

Along with this ideological component, it is also important to highlight the strategic aspect; we are dealing with a question of nationalism, of defending patriotic interests. Since the emergence of the Taliban, Pakistan has not hesitated to support them for major strategic reasons, as there has always been a fear that an unstable Afghanistan would end up being controlled directly or indirectly by India, an encircle strategy[4]. Faced with this dangerous scenario, the Taliban are Islamabad's only asset on the ground. It is for this reason, and not only for religious commitment, that this bond is produced, although over time it is strengthened and expanded. Therefore, at first, it is Pakistani nationalism and its foreign interests that are the cause of this situation, it seeks to influence neighboring Afghanistan to make the situation as beneficial as possible for Pakistan. Later on, when we discuss the situation of the Taliban on the national territory, we will address the issue of Pakistani nationalism and how its weak construction causes great problems for the state itself. But on Afghan territory, from what has been explained above, we can conclude that this relationship will continue shortly, it does not seem likely that this will change unless there are great changes of impossible prediction. The ISI will continue to have a significant influence on these groups and will continue its covert operations to promote and defend the Taliban, although it should be noted that the peace treaty between the Taliban and the US[5] is an important factor to take into account, this issue will be developed once the situation of the Taliban at the internal level is explained.

2.2. The Pakistani Taliban (Al-Qaeda[6] and the TTP)

The Taliban groups operating in Pakistan are an extension of those operating in neighboring Afghanistan. They belong to the same terrorist network and seek similar objectives, differentiated only by the place of action. Despite this obvious similarity, from Islamabad and increasingly from the whole of Pakistani society, the two groups are observed in a completely different way. On the one hand, as we said earlier, for most Pakistanis, the Afghan Taliban are fighting a legitimate and just war, that of liberating the region from foreign rule. However, groups operating in Pakistan are considered enemies of the state and the people. Although there was some support among the popular classes, especially in the Pashtun regions, this support has gradually been lost due to the multitude of atrocities against the civilian population that have recently been committed. The attack carried out by the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP)[7] in the Army Public School in Peshawar in the year 2014 generated a great stir in society, turning it against these radical groups. This duality marks Pakistan's strategy in dealing with terrorism both globally and internationally. While acting as an accomplice and protector of this groups in Afghanistan, he pursues his counterparts on their territory. We have to say that the operations carried out by the armed forces have been effective, especially the Zarb-e-Azb operation carried out in 2014 in North Waziristan, where the ISI played a fundamental role in identifying and classifying the different objectives. The position of the TTP in the region has been decimated, leaving it quite weakened. As can be seen in this scenario, there is no support at the institutional level from the ISI[8], as they are involved in the fight against these radical organizations. However, on an individual level if these informal links appear. This informal network is favored by the tribal character of Pakistani society, it can appear in different forms but often draw on ties of Kinship, friendship or social obligation[9]. Due to the nature of this type of relationship, it is impossible to know to what extent the ISI's activity is conditioned and how many of its members are linked to Taliban groups. However, we would like to point out that these unions are informal and individual and not institutional, which provides a certain degree of security and control, at least for the time being, the situation may vary greatly due to the lack of transparency.

2.3. ISI and the radical groups that operate in Kashmir

Another part of the board is made up of the radical groups that focus their terrorist attention on the conflict with India over control of Kashmir, the most important of which are: Lashkar-e-Taiba (Let) and Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM). Both groups have committed real atrocities over the past decades, the most notorious being the one committed by LeT in the Indian city of Mumbai in 2008. There are numerous testimonies, in particular, that of the American citizen David Haedy, which point to the cooperation of the ISI in carrying out the aforementioned attack.[10]

Recently, Hafiz Saeed, founder of Let and intellectual planner of the bloody attack, was arrested. The news generated some turmoil both locally and internationally and opened the debate as to whether Pakistan had finally decided to act against the radical groups operating in Kashmir. We are once again faced with a complex situation, although the arrest shows a certain amount of willpower, it is no more than a way of making up for the situation and relaxing international pressure. The above coincides with the FATF's[11] assessment of Pakistan's status within the institution, which is of great importance for the short-term future of the country's economy. Beyond rhetoric, there is no convincing evidence that suggests that Pakistan has made a move against those groups. The link and support provided by the ISI in this situation are again closely linked to strategic and ideological issues. Since its foundation, Pakistani foreign policy has revolved around India[12], as we saw on the Afghan stage. Pakistani nationalism is based on the maxim that India and the Hindus are the greatest threat to the future of the state. Given the significance of the conflict for Pakistani society, there has been no hesitation in using radical groups to gain advantages on the ground. From Pakistan perspective, it is considered that this group of terrorists are an essential asset when it comes to putting pressure on India and avoiding the complete loss of the territory, they are used as a negotiating tool and a brake on Indian interests in the region.

As we can see, the core between the ISI and certain terrorist groups is based on deep-seated nationalism, which has led both members of the ISI and society, in general, to identify with the ideas of certain radical groups. They have benefited from the situation by bringing together a huge amount of power, becoming a threat to the state itself. The latter has compromised the government of Pakistan, sometimes leaving it with little room for maneuver. The immense infrastructure and capacity of influence that Let has thanks to its charitable arm Jamaat-ud-Dawa, formed with re-localized terrorists, is a clear example of the latter. A revolt led by this group could put Islamabad in a serious predicament, so the actions taken both in Kashmir and internally to try to avoid the situation should be measured very well. The existing cooperation between the ISI and these radical groups is compromised by the development of the conflict in Kashmir, which may increase or decrease depending on the situation. What is certain, because of the above, is that it will not go unnoticed and will continue to play a key role in the future. These relationships, this two-way game could drag Pakistan soon into an internal conflict, which could compromise its very existence as a nation.

[1] Ahmed, Zobaer. "Is Pakistani Intelligence Radicalizing Rohingya Refugees? | DW | 13.02.2020". DW.COM, 2020.

[2] Idrees, Muhammad. Instability In Afghanistan: Implications For Pakistan. PDF, 2019.

[3] Lieven, Anatol. Pakistan a Hard Country. 1st ed. London: Penguin, 2012.

[4] United States Institute for Peace. The India-Pakistan Rivalry In Afghanistan, 2020.

[5] Maizland, Lindsay. "U.S.-Taliban Peace Deal: What To Know". Council On Foreign Relations, 2020.

[6] Blanchard, Christopher M. Al Qaeda: Statements And Evolving Ideology. PDF, 2007.

[7] Mapping Militant Organizations. “Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan.” Stanford University. Last modified July 2018.

[8] Gabbay, Shaul M. Networks, Social Capital, And Social Liability: The Cae Of Pakistan ISI, The Taliban And The War Against Terrorism.PDF, 2014. http://www.scirp.org/journal/sn.

[9] Lieven, Anatol. Pakistan a Hard Country. 1st ed. London: Penguin, 2012.

[10] Lieven, Anatol. Pakistan a Hard Country. 1st ed. London: Penguin, 2012.

[11] "Pakistan May Remain On FATF Grey List Beyond Feb 2020: Report". The Economic Times, 2019.

[12] "India And Pakistan: Forever Rivals?". Aljazeera.Com, 2017.

![Visión sobre extracción de minerales en un asteroide, de ExplainingTheFuture.com [Christopher Barnatt] Visión sobre extracción de minerales en un asteroide, de ExplainingTheFuture.com [Christopher Barnatt]](/documents/10174/16849987/gaj-foto-4.jpg)

▲ Visión sobre extracción de minerales en un asteroide, de ExplainingTheFuture.com [Christopher Barnatt]

GLOBAL AFFAIRS JOURNAL / Mario Pereira

[Documento de 14 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

[Documento de 14 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

INTRODUCCIÓN

Recuerda el astrofísico estadounidense, Michio Kaku, que cuando el presidente Thomas Jefferson compró Luisiana a Napoleón (en 1803) por la astronómica cifra de 15 millones de dólares, estuvo una larga temporada sumido en el más profundo espanto. La razón de ello estribaba en el hecho de que desconoció por largo tiempo si el referenciado territorio (en su mayor parte inexplorado) escondía fabulosas riquezas o, por el contrario, era un páramo sin mayor valor… El paso del tiempo demostró con creces lo primero, así como acreditó que fue entonces cuando se inició la marcha de los pioneros americanos: aquellos sujetos que –al igual que los “Adelantados” castellanos y extremeños en el siglo XVI– se lanzaban hacia lo desconocido en aras de obtener fortuna, descubrir nuevas maravillas y mejorar su posición social.

Los Jefferson de hoy en día, son los Musk y los Bezos, empresarios norteamericanos dueños de enormes emporios financieros, comerciales y tecnológicos, quienes, de la mano de nuevos “pioneros” (un mix entre Julio Verne/Arthur C. Clark y Neil Amstrong/John Glenn) buscan alcanzar la nueva frontera de la Humanidad: la explotación comercial y minera del Espacio Ultraterrestre.

Ante semejante desafío, muchas son las preguntas que podemos (y debemos) formularnos. Aquí intentaremos dar respuesta (siquiera someramente) a si la normativa internacional y nacional existente relativa a la explotación minera de la Luna y de los cuerpos celestes, constituye –o no–, un marco suficiente para la regulación de tales actividades proyectadas.

![Propuesta de base lunar para obtención de helio, tomada de ExplainingTheFuture.com [Christopher Barnatt] Propuesta de base lunar para obtención de helio, tomada de ExplainingTheFuture.com [Christopher Barnatt]](/documents/10174/16849987/gaj-foto-3.jpg)

▲ Propuesta de base lunar para obtención de helio, tomada de ExplainingTheFuture.com [Christopher Barnatt]

GLOBAL AFFAIRS JOURNAL / Emili J. Blasco

[Documento de 8 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

[Documento de 8 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

INTRODUCCIÓN

El interés económico por los recursos del espacio, o al menos la expectativa razonable acerca de la rentabilidad que puede suponer su obtención, explica en gran medida la creciente implicación de la inversión privada en los viajes espaciales.

Más allá de la industria relacionada con los satélites artificiales, de gran pujanza comercial, y también de la que sirve a propósitos científicos y de defensa, donde el sector estatal sigue teniendo un papel dirigente, la posibilidad de explotar materias primas de alto valor presentes en los cuerpos celestes –de entrada, en los asteroides más próximos a la Tierra y en la Luna– ha despertado una suerte de fiebre del oro que está alentando la nueva carrera espacial.

La épica de los nuevos barones del espacio –Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos– ha acaparado el relato público, pero junto a ellos existen otros New Space Players, de perfiles variados. Detrás de todos hay un creciente grupo de socios capitalistas e inquietos inversores dispuestos a arriesgar activos en espera de ganancias.

Hablar de fiebre resulta ciertamente exagerado por cuanto aún está por demostrar el provecho económico real que puede lograrse de la minería espacial –la obtención de platino, por ejemplo, o del helio lunar–, pues si bien se está dando un abaratamiento de la tecnología que financieramente permite dar nuevos pasos en el espacio exterior, traer a la Tierra toneladas de materiales tiene un coste que en la mayoría de los casos resta sentido monetario a la operación.

Bastaría, no obstante, que en ciertas situaciones fuera rentable para que se incrementara el número de misiones espaciales, y se supone que ese tráfico por sí mismo generaría la necesidad de una infraestructura en el exterior, al menos con estaciones donde repostar combustible –tan caro de elevar al firmamento–, fabricado a partir de materia prima hallada en el espacio (el agua de los polos lunares se podría transformar en propelente). Es esa expectativa, con cierta base de razonabilidad, la que alimenta las inversiones que se están realizando.

A su vez, la mayor actividad espacial y la competencia por obtener los recursos buscados proyectan más allá de nuestro planeta los conceptos de la geopolítica desarrollados para la Tierra. La ubicación de los países (hay localizaciones especialmente adecuadas para los lanzamientos espaciales) y el control de ciertas rutas (la sucesión de las órbitas más convenientes en los vuelos) son parte de la nueva astropolítica.

![Avión espacial no tripulado estadounidense X-37B, al regreso de su cuarta misión, en 2017 [US Air Force] Avión espacial no tripulado estadounidense X-37B, al regreso de su cuarta misión, en 2017 [US Air Force]](/documents/10174/16849987/gaj-foto-2.jpg)

▲ Avión espacial no tripulado estadounidense X-37B, al regreso de su cuarta misión, en 2017 [US Air Force]

GLOBAL AFFAIRS JOURNAL / Luis V. Pérez Gil

[Documento de 10 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

[Documento de 10 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

INTRODUCCIÓN

La militarización del espacio es una realidad. Las grandes potencias han dado el paso de poner en órbita satélites que pueden atacar y destruir los aparatos espaciales del adversario o de terceros Estados. Las consecuencias para el que sufre estos ataques pueden ser catastróficas, porque sus sistemas de comunicaciones, de navegación y de defensa quedarán parcial o totalmente inutilizados. Este escenario plantea, como en la guerra nuclear, la posibilidad de un ataque preventivo destinado a evitar quedar en manos del adversario en un eventual conflicto bélico. Los Estados Unidos y Rusia disponen de la capacidad de realizar estas acciones, pero el resto de potencias no quieren estar a la zaga. El resto intenta seguir a las grandes potencias, que son las que dictan las reglas del sistema.

Las grandes potencias se disputan también en el espacio el mantenimiento de la primacía en el sistema internacional global y tratan de asegurarse de que, en caso de enfrentamiento, puedan inutilizar y destruir la capacidad de mando y control, comunicaciones, inteligencia, vigilancia y reconocimiento (ISR) del adversario, porque sin satélites se reduce su capacidad de defensa frente al poder demoledor de las armas guiadas de precisión. De ello se deduce la regla de que quien domine el espacio dominará la Tierra en un conflicto bélico.

Este es uno de los principios fundamentales de la obra de Friedman sobre el poder en las relaciones internacionales en este siglo, cuando afirma que las guerras del futuro se librarán en el espacio porque los adversarios buscarán destruir los sistemas espaciales que les permiten seleccionar objetivos y los satélites de navegación y comunicaciones para inutilizar su capacidad bélica.

En consecuencia, tanto los Estados Unidos como Rusia, y también China, financian grandes programas espaciales y desarrollan nuevas tecnologías destinadas a obtener satélites no convencionales y aviones espaciales, por lo que se puede hablar sin ambages de la militarización del espacio, como veremos en los siguientes epígrafes.

Pero, antes de continuar, debemos recordar que existe un tratado internacional de carácter multilateral, denominado Tratado sobre el Espacio Ultraterrestre, que firmaron inicialmente los Estados Unidos, el Reino Unido y la Unión Soviética el 27 de enero de 1967, que establece una serie de limitaciones a las operaciones en el espacio. Según este tratado cualquier país que lance un objeto al espacio “retendrá su jurisdicción y control sobre tal objeto, así como sobre todo el personal que vaya en él, mientras se encuentre en el espacio o en cuerpo celeste” (artículo 8). También establece que cualquier país “será responsable internacionalmente de los daños causados a otro Estado parte (…) por dicho objeto o sus partes componentes en la Tierra, en el espacio aéreo o en el espacio ultraterrestre” (artículo 7). Esto significa que cualquier satélite espacial puede acercarse a un aparato de otro país, seguirlo o realizar observaciones remotas, pero no puede alterar o interrumpir su operatividad de ninguna manera. Es preciso aclarar que, aunque estén prohibidas las armas nucleares y las de destrucción masiva en el espacio, no existe ninguna limitación a la instalación de armas convencionales en los satélites espaciales. A instancias de Rusia y China la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas ha venido impulsando desde 2007 un proyecto de tratado multilateral que prohíba las armas en el espacio exterior, el uso de la fuerza o la amenaza de uso contra objetos espaciales, pero ha sido rechazado sistemáticamente por los Estados Unidos.

![Además del regreso a la Luna y la llegada a Marte, también se aceleran programas de viajes a asteroides [NASA] Además del regreso a la Luna y la llegada a Marte, también se aceleran programas de viajes a asteroides [NASA]](/documents/10174/16849987/gaj-foto-1.jpg)

▲ Además del regreso a la Luna y la llegada a Marte, también se aceleran programas de viajes a asteroides [NASA]

GLOBAL AFFAIRS JOURNAL / Javier Gómez-Elvira

[Documento de 8 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

[Documento de 8 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

INTRODUCCIÓN

Desde tiempos inmemoriales el ser humano se ha imaginado fuera de la Tierra, explorando otros mundos. Uno de los primeros relatos data del siglo II d.C., Luciano de Samosata escribía un libro en el que sus personajes llegaban a la Luna gracias al impulso de un remolino de viento y allí desarrollaban sus aventuras. Desde entonces se pueden encontrar numerosas novelas o relatos de ciencia ficción que discurrían en la Luna, en Marte, otros cuerpos de nuestro Sistema Solar o incluso más allá. De alguna forma todos ellos perdieron un poco de su ficción a mediados del siglo pasado, con los primeros pasos de un astronauta en nuestro satélite. Aunque desgraciadamente lo que parecía el inicio de una nueva era no fue más allá de 5 misiones a lo largo de 2 años.

La primera etapa se inició cuando el presidente Kennedy pronunció su famosa frase: “We choose to go to the Moon... We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others, too”. Aunque quizás en el comienzo estaba escrito el final: el único objetivo era demostrar que EEUU eran los líderes tecnológicos por encima de la URSS, y cuando esto se consiguió el proyecto se paró.

![Escena sobre anclaje en un asteroide para desarrollar actividad minera, de ExplainingTheFuture.com [Christopher Barnatt] Escena sobre anclaje en un asteroide para desarrollar actividad minera, de ExplainingTheFuture.com [Christopher Barnatt]](/documents/10174/16849987/gaj-foto-0.jpg)

▲ Escena sobre anclaje en un asteroide para desarrollar actividad minera, de ExplainingTheFuture.com [Christopher Barnatt]

GLOBAL AFFAIRS JOURNAL / Emili J. Blasco

[Documento de 8 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

[Documento de 8 páginas. Descargar en PDF]

INTRODUCCIÓN

La nueva carrera espacial se asienta sobre fundamentos más sólidos y duraderos –especialmente el interés económico– que la primera, que estuvo basada en la competencia ideológica y el prestigio internacional. En la nueva Guerra Fría hay también desarrollos espaciales que obedecen a la pugna estratégica de las grandes potencias, como ocurrió entre las décadas de 1950 y de 1970, pero hoy a los aspectos de exploración y defensa se unen también los intereses comerciales: las empresas están tomado el relevo en muchos aspectos al protagonismo de los Estados.

Por más que resulte discutible hablar de nueva era espacial, dado que desde el emblemático lanzamiento del Sputnik en 1957 no ha dejado de programarse actividad en distintas regiones del espacio, incluida la presencia humana (aunque acabaron los viajes tripulados a la Luna, ha habido viajes y estancias en la baja órbita terrestre), lo cierto es que hemos entrado en una nueva fase.

Hollywood, que tan bien refleja la realidad social y las aspiraciones generacionales de cada tiempo, sirve de espejo. Después de un tiempo sin especiales producciones relativas al espacio, desde 2013 el género vive un resurgimiento, con nuevos matices. Películas como Gravity, Interstellar y Marte ilustran el momento del despegue de una renovada ambición que, tras el horizonte corto del programa de transbordadores –reconocido como un error por la NASA, al focalizarse en la órbita baja de la Tierra–, entronca con la secuencia lógica de las perspectivas que abría la llegada del hombre a la Luna: bases lunares, viajes tripulados a Marte y colonización del espacio.

A nivel de imaginario colectivo, la nueva era espacial parte de la casilla donde “terminó” la previa, aquel día de diciembre de 1972 en que Gene Cernan, astronauta del Apolo 17, abandonó la Luna. De algún modo, en todo este tiempo se ha dado “la tristeza de pensar que en 1973 habíamos alcanzado como especie el punto máximo de nuestra evolución” y que después aquello se paró: “mientras crecíamos nos prometieron mochilas-cohete, y a cambio tenemos Instagram”, constata el gráfico comentario de uno de los coguionistas de Interstellar.

Algo parecido es lo que había expresado George W. Bush cuando en 2004 encargó a la NASA comenzar a preparar la vuelta del hombre a la Luna: “En los últimos treinta años, ningún ser humano ha puesto el pie en otro mundo o se ha aventurado en el espacio más allá de 386 millas [621 kilómetros de altitud], aproximadamente la distancia de Washington, DC, a Boston, Massachusetts”.

Podría fijarse ese 2004 como el comienzo de la nueva era espacial, no solo porque desde entonces viajes tripulados a la Luna y a Marte vuelven a estar en la mirilla de la NASA, sino porque entonces tuvo lugar lo que se ha considerado como el primer hito de la exploración espacial privada con el vuelo experimental del SpaceShipOne: era el primer acceso de un piloto particular al espacio orbital, algo que hasta entonces era considerado como un ámbito exclusivo del gobierno.

La prioridad estadounidense pasó luego de la Luna a alguno de los asteroides y después a Marte, para volver a ocupar el viaje a nuestro satélite el primer lugar de la agenda espacial. Regresando a la Luna la idea de “vuelta” a la exploración del espacio adquiere una especial significación.

GLOBAL AFFAIRS JOURNAL #2 / Marzo 2020

[Descargar el PDF del Journal completo]

[Descargar el PDF del Journal completo]

El horizonte vuelve a estar arriba:

Potencias y empresas pugnan por el espacio

PRESENTACIÓN

Asistimos a una nueva era espacial, que está aquí para quedarse. Esta vez va en serio. No será un cultivo de una sola floración, como la llegada del ser humano a la Luna, que pronto se agosta. El regreso de la tensión geopolítica a la Tierra tiene también su proyección en el espacio, concebido no ya como un lugar de incursión o territorio de apoyo estratégico sino como un dominio en sí mismo, de la misma importancia y proximidad que los otros (tierra, mar, aire... y red). Aunque la prioridad espacial de las superpotencias pueda verse modulada en función de los vaivenes de las relaciones internacionales, es tal la dependencia de los satélites artificiales adquirida por la humanidad que el espacio forma ya parte definitivamente de nuestro directo entorno. Con todo, es el despertado interés económico por las perspectivas de negocio del sector espacial, manifestado en la carrera de diversas empresas privadas por hacerse con actividades que antes, por las ingentes exigencias presupuestarias, solo asumían ciertos estados, lo que asegura la continuidad de una etapa que se abre para no cerrarse.

El horizonte vuelve a esta arriba –regreso a la Luna, vuelo a Marte, minería de asteroides– tras los esfuerzos no sostenidos llevados a cabo hace medio siglo. A ese horizonte hemos querido dedicar la edición de Global Affairs Journal de este año, después del lanzamiento de esta publicación de carácter monográfico en 2019 con el foco en otra cuestión de gran importancia estratégica, la geopolítica de la demografía y los retos demográficos de las grandes potencias. Así que bienvenidos y ¡buen viaje a las estrellas!

Índice

EL HORIZONTE VUELVE A ESTAR ARRIBA:

POTENCIAS Y EMPRESAS PUGNAN POR EL ESPACIO

Presentación

p. 5 [versión PDF]

ESPACIO: NUEVO DOMINIO MILITAR Y ECONÓMICO

Introducción del director de GASS

p. 6-13 [versión PDF]

VUELTA A LA EXPLORACIÓN DEL ESPACIO

Javier Gómez-Elvira

Director del Departamento de Cargas Útiles de INTA

p. 14-21 [versión PDF]

LA MILITARIZACIÓN DEL ESPACIO:

EL DESARROLLO DE SATÉLITES INSPECTORES

Luis V. Pérez Gil

Experto en Fuerza Espacial, Universidad de La Laguna

p. 22-31 [versión PDF]

CARRERA POR LOS RECURSOS ESPACIALES:

DE LA MINERÍA AL CONTROL DE RUTAS

Emili J. Blasco

Profesor de Geopolítica Aplicada, Universidad de Navarra

p. 32-39 [versión PDF]

MARCOS INTERNACIONALES RELEVANTES PARA

LA EXTRACCIÓN Y USO DE RECURSOS ESPACIALES

Mario Pereira

Profesor de Derecho, Universidad de Navarra

p. 40-54 [versión PDF]

LECTURAS RECOMENDADAS

L. V. Pérez Gil, E. J. Blasco

Ramón Barba, Ángel Martos

p. 54-56 [versión PDF]

![Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, also called Kartarpur Sahib, is a Sikh holy place in Kartarpur, in the Pakistani Punjab [Wikimedia Commons] Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, also called Kartarpur Sahib, is a Sikh holy place in Kartarpur, in the Pakistani Punjab [Wikimedia Commons]](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-punjab-blog.jpg)

▲ Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, also called Kartarpur Sahib, is a Sikh holy place in Kartarpur, in the Pakistani Punjab [Wikimedia Commons]

ESSAY / Pablo Viana

Punjab region has been part of India until the year 1947, when the Punjab province of British India was divided in two parts, East Punjab (India) and West Punjab (Pakistan) due to religious reasons. After the division a lot of internal violence occurred, and many people were displaced.

East and West Punjab

The partition of Punjab proved to be one of the most violent, brutal, savage debasements in the history of humankind. The undivided Punjab, of which West Punjab forms a major region today, was home to a large minority population of Punjabi Sikhs and Hindus unto 1947 apart from the Muslim majority[1]. This minority population of Punjabi Sikhs called for the creation of a new state in the 1970s, with the name of Khalistan, but it was detained by India, sending troops to stop the militants. Terrorist attacks against the Sikh majority emerged, by those who did not accept the creation of the state of Khalistan and wished to stay in India.

The Sikh population is the dominant religious ethnicity in East Punjab (58%) followed by the Hindu (39%). Sikhism and Islamism are both monotheistic religions, they do believe on the same concept of God, although it is different on each religion. Sikhism was developed during the 16th and 17th century in the context of conflict in between Hinduism and Islamism. It is important to mention Sikhism if we talk about Punjab, as its origins were in Punjab, but most important in recent times, is that the Guru Nanak Dev[2] was buried in Pakistani territory. Four kilometres from the international border the Sikh shrine was conceded to Pakistan at the time of British India’s Partition in 1947. For followers of Sikhism this new border that cut through Punjab proved especially problematic. Sikhs overwhelmingly chose India over the newly formed Pakistan as the state that would best protect their interests (there are an estimated 50,000 Sikhs living in Pakistan today, compared to the 24 million in India). However, in making this choice, Sikhs became isolated from several holy sites, creating a religious disconnection that has proved a constant spiritual and emotional dilemma for the community[3].

In order to let the Sikhist population visit the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib[4], the Kartarpur Corridor was created in November 2019. However, there is an incessant suspicion in between India and Pakistan that question Pakistan motives. Although it seems like a generous move work of the Pakistani government, there is a clear perception that Pakistan is engaged in an act of deception[5]. Thus, although this scenario might seem at first beneficial for the rapprochement of East and West Punjab, it is not at all. Pakistan is involved in a rhetorical policy which could end up worsening its relations with India.

The division of Punjab in 1947 was like the division of Pakistan and India on that same year. Territorial disputes have been an issue that defines very well India-Pakistan relations since the independence. In the case of Punjab, there has not been a territorial debate. The division was clear and has been respected ever since. Why would Pakistan and/or India be willing to unify Punjab? There is no reason. East and West Punjab represent two different nations and three religions. If we think about reunifying Pakistan and India, the conclusion is the same (although more dramatic); too many discrepancies and recent unrest to think about bringing back together the nations. However, if the Kartarpur Corridor could be placed out of bonds for the territorial disputes between Pakistan and India (e.g. Kashmir), Islamabad and New Delhi could use this situation as a model to find out which are the pressure points and trying to find a path for identifying common solutions. In order to achieve this, there should be a clear behaviour by both parts of cooperation. Sadly, in recent times both Pakistan and India have discrepancies regarding many topics and suspicious behaviours that clearly show that they won’t be interested in complicating more the situation in Punjab searching for unification. The riots of 1947 left a terrific era on the region and now that both sides are established and no major disputes have emerged (except for Sikh nationalism), the situation should and will most likely remain as it is.

The Indus Water Treaty

The Indus Waters Treaty was signed in 1960 after nine years of negotiations between India and Pakistan with the help of the World Bank, which is also a signatory. Seen as one of the most successful international treaties, it has survived frequent tensions, including conflict, and has provided a framework for irrigation and hydropower development for more than half a century. The Treaty basically provides a mechanism for exchange of information and cooperation between Pakistan and India regarding the use of their rivers. This mechanism is well known as the Permanent Indus Commission. The Treaty also sets forth distinct procedures to handle issues which may arise: “questions” are handled by the Commission; “differences” are to be resolved by a Neutral Expert; and “disputes” are to be referred to a seven-member arbitral tribunal called the “Court of Arbitration.” As a signatory to the Treaty, the World Bank’s role is limited and procedural[6].

Since 1948, India has been confident on the fact that East Punjab and the acceding states have a prior and superior claim to the rivers flowing through their territory. This leaves West Punjab in disadvantage regarding water resources, as East Punjab can access the highest sections of the rivers. Even under a unified control designed to ensure equitable distribution of water, in years of low river flow cultivators on tail distributaries always tended to accuse those on the upper reaches of taking an undue amount of the water, and after partition any temporary shortage, whatever the cause, could easily be attributed to political motives. It was therefore wise of Pakistan-indeed it became imperative-to cut the new feeder from the Ravi for this area and thus become independent of distributaries in East Punjab[7]. The Treaty acknowledges the control of the eastern rivers to India, and to the western rivers to Pakistan.

The main issue of water distribution in between East and West Punjab is then a matter of geography. Even though West Punjab covers more territory than East Punjab, and the water flow of West Punjab is almost three times the water flow of East Punjab rivers, the Indus Water Treaty gives the following advantage to India: since Pakistan rivers receive much more water flow from India, the treaty allowed India to use western rivers water for limited irrigation use and unlimited use for power generation, domestic, industrial and non-consumptive uses such as navigation, floating of property, fish culture and this is where the disputes mainly came from, as Pakistan has objected all Indian hydro-electric projects on western rivers irrespective of size and layout.

It is worth mentioning that with the World Bank mediating the Treaty in between India and Pakistan, the water access will not be curtailed, and since the ratification of the Treaty, India and Pakistan have not engaged in any water wars. Although there have been many tensions the disputes have been via legal procedures, but they haven’t caused any major cause for conflict. Today, both countries are strengthening their relationship, and the scenario is not likely to get worse, it is actually the opposite, and the Indus Water Treaty is one of the few livelihoods of the relationship. If the tensions do not cease, the World Bank should consider the possibility of amending the treaty, obviously if both Pakistan and India are willing to cooperate, although with the current environment, a renegotiation of the treaty would probably bring more complications. There is no shred of evidence that India has violated the Indus Water Treaty or that it is stealing Pakistan’s water[8], although Pakistan does blame India for breaching the treaty, as showed before. This is pointed out by Hindu politicians as an attempt by Pakistan to divert the attention of its own public from the real issues of gross mismanagement of water resources[9].

Pakistan has a more hostile attitude regarding water distribution, trying to find a way to impeach India, meanwhile India focuses on the development of hydro-electric projects. India won’t stop providing water to the West Punjab, as the treaty is still in force and is fulfilled by both parts. Pakistan should reconsider its role and its benefits received thanks to the treaty and meditate about the constant pressure towards India, as pushing over the limit could mean a more hostile activity carried out by India, which in the worst case scenario (although not likely to happen) could mean a breakdown of the treaty.

[1] The Punjab in 1920s – A Case study of Muslims, Zarina Salamat, Royal Book Company, Karachi, 1997. table 45, pp. 136.

[2] Guru Nanak Dev was the founder of Sikhism (1469-1540)

[3] Wyeth, G. (Dec 28, 2019). Opening the Gates: The Kartarpur Corridor. Australian Institute of International Affairs.

[4] Site where Guru Nanak Dev settled the Sikh community, and lived for 18 years after his death in 1539.

[5] Islamabad promoted the activity of Sikhs For Justice including the will to establish the state of Khalistan.

[6] World Bank (June 11, 2018). Fact Sheet: The Indus Waters Treaty 1960 and the Role of the World Bank.

[7] F.J. Fowler (Oct 1950) Some Problems of Water Distribution between East and West Punjab p. 583-599.

[8] S. Chandrasekharan (Dec 11, 2017) Indus Water Treaty: Review is not an Option South Asia Analysis Group.

[9] Mohan, G. (Feb 3, 2020). India rejects Pakistan media report on Indus water sharing India Today.

Showing 131 to 140 of 421 entries.

[

[