Breadcrumb

Blogs

Entries with tag india-pakistán .

![Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, also called Kartarpur Sahib, is a Sikh holy place in Kartarpur, in the Pakistani Punjab [Wikimedia Commons] Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, also called Kartarpur Sahib, is a Sikh holy place in Kartarpur, in the Pakistani Punjab [Wikimedia Commons]](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-punjab-blog.jpg)

▲ Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, also called Kartarpur Sahib, is a Sikh holy place in Kartarpur, in the Pakistani Punjab [Wikimedia Commons]

ESSAY / Pablo Viana

Punjab region has been part of India until the year 1947, when the Punjab province of British India was divided in two parts, East Punjab (India) and West Punjab (Pakistan) due to religious reasons. After the division a lot of internal violence occurred, and many people were displaced.

East and West Punjab

The partition of Punjab proved to be one of the most violent, brutal, savage debasements in the history of humankind. The undivided Punjab, of which West Punjab forms a major region today, was home to a large minority population of Punjabi Sikhs and Hindus unto 1947 apart from the Muslim majority[1]. This minority population of Punjabi Sikhs called for the creation of a new state in the 1970s, with the name of Khalistan, but it was detained by India, sending troops to stop the militants. Terrorist attacks against the Sikh majority emerged, by those who did not accept the creation of the state of Khalistan and wished to stay in India.

The Sikh population is the dominant religious ethnicity in East Punjab (58%) followed by the Hindu (39%). Sikhism and Islamism are both monotheistic religions, they do believe on the same concept of God, although it is different on each religion. Sikhism was developed during the 16th and 17th century in the context of conflict in between Hinduism and Islamism. It is important to mention Sikhism if we talk about Punjab, as its origins were in Punjab, but most important in recent times, is that the Guru Nanak Dev[2] was buried in Pakistani territory. Four kilometres from the international border the Sikh shrine was conceded to Pakistan at the time of British India’s Partition in 1947. For followers of Sikhism this new border that cut through Punjab proved especially problematic. Sikhs overwhelmingly chose India over the newly formed Pakistan as the state that would best protect their interests (there are an estimated 50,000 Sikhs living in Pakistan today, compared to the 24 million in India). However, in making this choice, Sikhs became isolated from several holy sites, creating a religious disconnection that has proved a constant spiritual and emotional dilemma for the community[3].

In order to let the Sikhist population visit the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib[4], the Kartarpur Corridor was created in November 2019. However, there is an incessant suspicion in between India and Pakistan that question Pakistan motives. Although it seems like a generous move work of the Pakistani government, there is a clear perception that Pakistan is engaged in an act of deception[5]. Thus, although this scenario might seem at first beneficial for the rapprochement of East and West Punjab, it is not at all. Pakistan is involved in a rhetorical policy which could end up worsening its relations with India.

The division of Punjab in 1947 was like the division of Pakistan and India on that same year. Territorial disputes have been an issue that defines very well India-Pakistan relations since the independence. In the case of Punjab, there has not been a territorial debate. The division was clear and has been respected ever since. Why would Pakistan and/or India be willing to unify Punjab? There is no reason. East and West Punjab represent two different nations and three religions. If we think about reunifying Pakistan and India, the conclusion is the same (although more dramatic); too many discrepancies and recent unrest to think about bringing back together the nations. However, if the Kartarpur Corridor could be placed out of bonds for the territorial disputes between Pakistan and India (e.g. Kashmir), Islamabad and New Delhi could use this situation as a model to find out which are the pressure points and trying to find a path for identifying common solutions. In order to achieve this, there should be a clear behaviour by both parts of cooperation. Sadly, in recent times both Pakistan and India have discrepancies regarding many topics and suspicious behaviours that clearly show that they won’t be interested in complicating more the situation in Punjab searching for unification. The riots of 1947 left a terrific era on the region and now that both sides are established and no major disputes have emerged (except for Sikh nationalism), the situation should and will most likely remain as it is.

The Indus Water Treaty

The Indus Waters Treaty was signed in 1960 after nine years of negotiations between India and Pakistan with the help of the World Bank, which is also a signatory. Seen as one of the most successful international treaties, it has survived frequent tensions, including conflict, and has provided a framework for irrigation and hydropower development for more than half a century. The Treaty basically provides a mechanism for exchange of information and cooperation between Pakistan and India regarding the use of their rivers. This mechanism is well known as the Permanent Indus Commission. The Treaty also sets forth distinct procedures to handle issues which may arise: “questions” are handled by the Commission; “differences” are to be resolved by a Neutral Expert; and “disputes” are to be referred to a seven-member arbitral tribunal called the “Court of Arbitration.” As a signatory to the Treaty, the World Bank’s role is limited and procedural[6].

Since 1948, India has been confident on the fact that East Punjab and the acceding states have a prior and superior claim to the rivers flowing through their territory. This leaves West Punjab in disadvantage regarding water resources, as East Punjab can access the highest sections of the rivers. Even under a unified control designed to ensure equitable distribution of water, in years of low river flow cultivators on tail distributaries always tended to accuse those on the upper reaches of taking an undue amount of the water, and after partition any temporary shortage, whatever the cause, could easily be attributed to political motives. It was therefore wise of Pakistan-indeed it became imperative-to cut the new feeder from the Ravi for this area and thus become independent of distributaries in East Punjab[7]. The Treaty acknowledges the control of the eastern rivers to India, and to the western rivers to Pakistan.

The main issue of water distribution in between East and West Punjab is then a matter of geography. Even though West Punjab covers more territory than East Punjab, and the water flow of West Punjab is almost three times the water flow of East Punjab rivers, the Indus Water Treaty gives the following advantage to India: since Pakistan rivers receive much more water flow from India, the treaty allowed India to use western rivers water for limited irrigation use and unlimited use for power generation, domestic, industrial and non-consumptive uses such as navigation, floating of property, fish culture and this is where the disputes mainly came from, as Pakistan has objected all Indian hydro-electric projects on western rivers irrespective of size and layout.

It is worth mentioning that with the World Bank mediating the Treaty in between India and Pakistan, the water access will not be curtailed, and since the ratification of the Treaty, India and Pakistan have not engaged in any water wars. Although there have been many tensions the disputes have been via legal procedures, but they haven’t caused any major cause for conflict. Today, both countries are strengthening their relationship, and the scenario is not likely to get worse, it is actually the opposite, and the Indus Water Treaty is one of the few livelihoods of the relationship. If the tensions do not cease, the World Bank should consider the possibility of amending the treaty, obviously if both Pakistan and India are willing to cooperate, although with the current environment, a renegotiation of the treaty would probably bring more complications. There is no shred of evidence that India has violated the Indus Water Treaty or that it is stealing Pakistan’s water[8], although Pakistan does blame India for breaching the treaty, as showed before. This is pointed out by Hindu politicians as an attempt by Pakistan to divert the attention of its own public from the real issues of gross mismanagement of water resources[9].

Pakistan has a more hostile attitude regarding water distribution, trying to find a way to impeach India, meanwhile India focuses on the development of hydro-electric projects. India won’t stop providing water to the West Punjab, as the treaty is still in force and is fulfilled by both parts. Pakistan should reconsider its role and its benefits received thanks to the treaty and meditate about the constant pressure towards India, as pushing over the limit could mean a more hostile activity carried out by India, which in the worst case scenario (although not likely to happen) could mean a breakdown of the treaty.

[1] The Punjab in 1920s – A Case study of Muslims, Zarina Salamat, Royal Book Company, Karachi, 1997. table 45, pp. 136.

[2] Guru Nanak Dev was the founder of Sikhism (1469-1540)

[3] Wyeth, G. (Dec 28, 2019). Opening the Gates: The Kartarpur Corridor. Australian Institute of International Affairs.

[4] Site where Guru Nanak Dev settled the Sikh community, and lived for 18 years after his death in 1539.

[5] Islamabad promoted the activity of Sikhs For Justice including the will to establish the state of Khalistan.

[6] World Bank (June 11, 2018). Fact Sheet: The Indus Waters Treaty 1960 and the Role of the World Bank.

[7] F.J. Fowler (Oct 1950) Some Problems of Water Distribution between East and West Punjab p. 583-599.

[8] S. Chandrasekharan (Dec 11, 2017) Indus Water Treaty: Review is not an Option South Asia Analysis Group.

[9] Mohan, G. (Feb 3, 2020). India rejects Pakistan media report on Indus water sharing India Today.

![Prime Minister Imran Kahn, at the United Nations General Assembly, in 2019 [UN] Prime Minister Imran Kahn, at the United Nations General Assembly, in 2019 [UN]](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-introduccion-blog.jpg)

▲ Prime Minister Imran Kahn, at the United Nations General Assembly, in 2019 [UN]

ESSAY / M. Biera, H. Labotka, A. Palacios

The geographical location of a country is capable of determining its destiny. This is the thesis defended by Whiting Fox in his book "History from a Geographical Perspective". In particular, he highlights the importance of the link between history and geography in order to point to a determinism in which a country's aspirations are largely limited (or not) by its physical place in the world.[1]

Countries try to overcome these limitations by trying to build on their internal strengths. In the case of Pakistan, these are few, but very relevant in a regional context dominated by the balance of power and military deterrence.

The first factor that we highlight in this sense is related to Pakistan's nuclear capacity. In spite of having officially admitted it in 1998, Pakistan has been a country with nuclear capacity, at least, since Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's government started its nuclear program in 1974 under the name of Project-706 as a reaction to the once very advanced Indian nuclear program.[2]

The second factor is its military strength. Despite the fact that they have publicly refused to participate in politics, the truth is that all governments since 1947, whether civil or military, have had direct or indirect military support.[3] The governments of Ayub Khan or former army chief Zia Ul-Haq, both through a coup d'état, are faithful examples of this capacity for influence.[4]

The existence of an efficient army provides internal stability in two ways: first, as a bastion of national unity. This effect is quite relevant if we take into account the territorial claims arising from the ethnic division caused by the Durand Line. Secondly, it succeeds in maintaining the state's monopoly on force, preventing its disintegration as a result of internal ethnic disputes and terrorism instigated by Afghanistan in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA region).[5]

Despite its internal strengths, Pakistan is located in one of the most insecure geographical areas in the world, where border conflicts are intermingled with religious and identity-based elements. Indeed, the endless conflict over Kashmir against India in the northeastern part of the Pakistani border or the serious internal situation in Afghanistan have been weighing down the country for decades, both geo-politically and economically. The dynamics of regional alliances are not very favourable for Pakistan either, especially when US preferences, Pakistan's main ally, seem to be mutating towards a realignment with India, Pakistan's main enemy.[6]

On the positive side, a number of projects are underway in Central Asia that may provide an opportunity for Pakistan to re-launch its economy and obtain higher standards of stability domestically. The most relevant is the New Silk Road undertaken by China. This project has Pakistan as a cornerstone in its strategy in Asia, while it depends on it to achieve an outlet to the sea in the eastern border of the country and investments exceeding 11 billion dollars are expected in Pakistan alone[7]. In this way, a realignment with China can help Pakistan combat the apparent American disengagement from Pakistani interests.

For all these reasons, it is difficult to speak of Pakistan as a country capable of carving out its own destiny, but rather as a country held hostage to regional power dynamics. Throughout this document, a review of the regional phenomena mentioned will be made in order to analyze Pakistan's behavior in the face of the different challenges and opportunities that lie ahead.

History

Right after the downfall of the British colony of the East Indies colonies in 1947 and the partition of India the Dominion of Pakistan was formed, now known by the title of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. The Partition of India divided the former British colony into two separated territories, the Dominion of Pakistan and the Dominion of India. By then, Pakistan included East Pakistan (modern day) Pakistan and Oriental Pakistan (now known as Bangladesh).

It is interesting to point out that the first form of government that Pakistan experienced was something similar to a democracy, being its founding father and first Prime Minister Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Political history in Pakistan consists of a series of eras, some democratically led and others ruled by the military branch which controls a big portion of the country.

—The rise of Pakistan as a Muslim democracy: 1957-1958. The era of Ali Jinnah and the First Indo-Pakistani war.

—In 1958 General Ayub Khan achieved to complete a coup d’état in Pakistan due to the corruption and instability.

—In 1971 General Khan resigned his position and appointed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto as president, but, lasted only 6 years. The political instability was not fruitful and rivalry between political parties was. But in 1977 General Zia-ul-Haq imposed a new order in Pakistan.

—From 1977 to 1988 Zia-ul-Haq imposed an Islamic state.

—In the elections of 1988 right after Zia-ul-Haq’s death, President Benazir Bhutto became the very first female leader of Pakistan. This period, up to 1999 is characterized by its democracy but also, by the Kargil War.

—In 1999 General Musharraf took control of the presidency and turned it 90º degrees, opening its economy and politics. In 2007 Musharraf announced his resignation leaving open a new democratic era characterized by the War on Terror of the United States in Afghanistan and the Premiership of Imran Khan.

Human and physical geography

The capital of Pakistan is Islamabad, and as of 2012 houses a population of 1,9 million people. While the national language of Pakistan is English, the official language is Urdu; however, it is not spoken as a native language. Afghanistan is Pakistan’s neighbor to the northwest, with China to the north, as well as Iran to the west, and India to the east and south.[8]

Pakistan is unique in the way that it possesses many a geological formation, like forests, plains, hills, etcetera. It sits along the Arabian Sea and is home to the northern Karakoram mountain range, and lies above Iranian, Eurasian and Indian tectonic plates. There are three dominant geographical regions that make up Pakistan: the Indus Plain, which owes its name to the river Indus of which Pakistan’s dominant rivers merge; the Balochistan Plateau, and the northern highlands, which include the 2nd highest mountain peak in the world, and the Mount Godwin Austen.[9] Pakistan’s traditional regions are a consequence of progression. These regions are echoed by the administrative distribution into the provinces of Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa which includes FATA (Federally Administered Tribal Areas) and Balochistan.

Each of these regions is “ethnically and linguistically distinct.”[10] But why is it important to understand Pakistan’s geography? The reason is, and will be discussed further in detail in this paper, the fact that “terror is geographical” and Pakistan is “at the epicenter of the neo-realist, militarist geopolitics of anti-terrorism and its well-known manifestation the ‘global war on terror’...”[11]

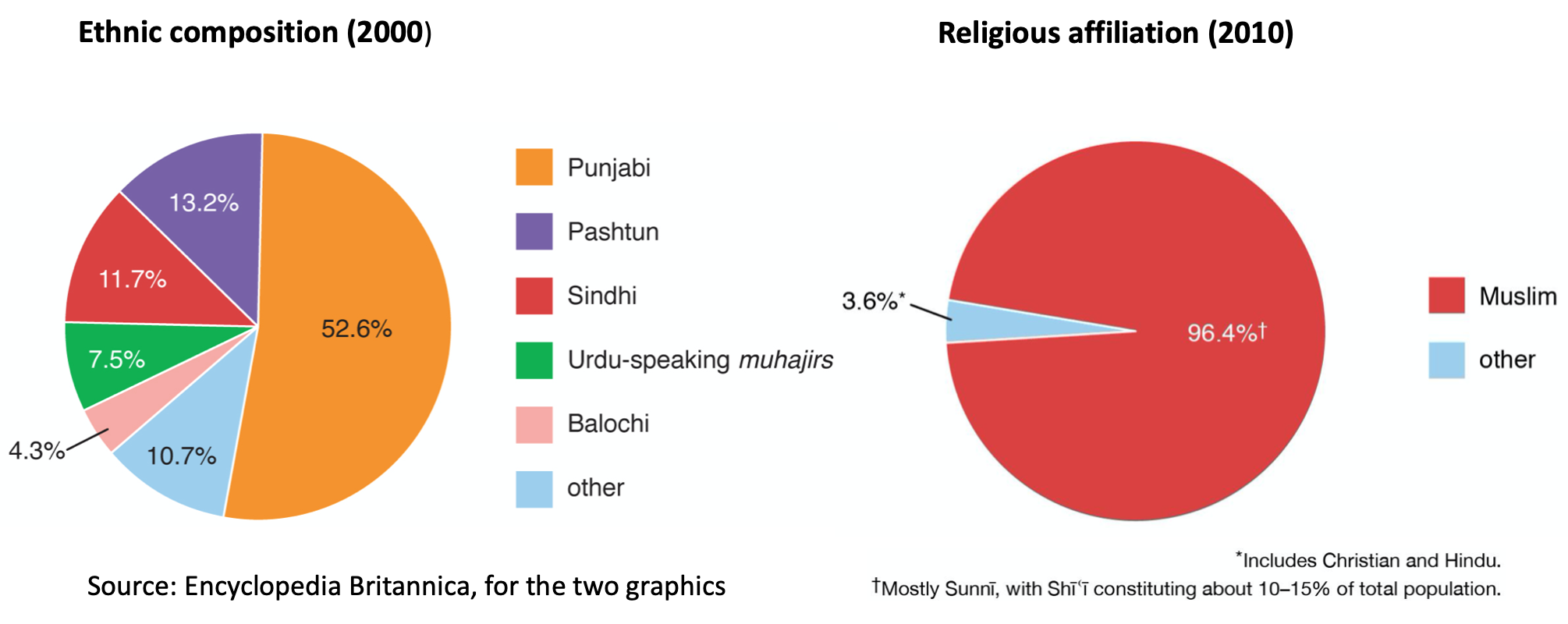

Punjabi make up more than 50% of the ethnic division in Pakistan, and the smallest division is the Balochi. We should note that Balochistan, however small, is an antagonistic region for the Pakistani government. The reason is because it is a “base for many extremist and secessionist groups.” This is also important because CPEC, the Chinese-Pakistan Economic Corridor, is anticipated to greatly impact the area, as a large portion of the initiative is to be constructed in that region. The impact of CPEC is hoped to make that region more economically stable and change the demography of this region.[12]

The majority of Pakistani people are Sunni Muslims, and maintain Islamic tradition. However, there is a significant number of Shiite Muslims. Religion in Pakistan is so important that it is represented in the government, most obviously within the Islamic Assembly (Jamāʿat-i Islāmī) party which was created in 1941.[13]

This is important. The reason being is that there is a history of sympithism for Islamic extremism by the government, and giving rise to the expansion of the ideas of this extremism. Historically, Pakistan has not had a strict policy against jihadis, and this lack of policy has poorly affected Pakistan’s foreign policy, especially its relationship with the United States, which will be touched upon in this paper.

Current Situation: Domestic politics, the military and the economy

Imran Khan was elected and took office on August 18th, 2018. Before then, the previous administrations had been overshadowed by suspicions of corruption. What also remained important was the fact that his election comes after years of a dominating political power, the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) and Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). Imran Khan’s party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) surfaced as the majority in the Pakistan’s National Assembly. However, there is some debate by specialists on how prepared the new prime minister is to take on this extensive task.

Economically, Pakistan was in a bad shape even before the global Coronavirus-related crisis. In October 2019, the IMF predicted that the country's GDP would increase only 2.4% in 2020, compared with 5,2% registered in 2017 and 5,5% in 2018; inflation would arrive to 13% in 2020, three times the registered figure of 2017 and 2018, and gross debt would peak at 78.6%, ten points up from 2017 and 2018.[14] This context led to the Pakistani government to ask for a loan to the IMF, and a $6 billion loan was agreed in July 2019. In addition, Pakistan got a $2 billion from China. Later on, because of the Covid-19 pandemic, the IMF worsened its estimations on Pakistan's economy, and predicted that its GDP would grow minus 1.5% in 2020 and 2% in 2021.[15]

Throughout its history, Pakistan has been a classic example of a “praetorian state”, where the military dominates the political institutions and regular functioning. The political evolution is represented by a routine change “between democratic, military, or semi military regime types.” There were three critical pursuits towards a democratic state that are worth mentioning, that started in 1972 and resulted in the rise of democratically elected leaders. In addition to these elections, the emergence of new political parties also took place, permitting us to make reference to Prime Minister Imran Khan’s party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI).[16]

Civilian - military relations are characterized by the understanding that the military is what ensures the country’s “national sovereignty and moral integrity”. There resides the ambiguity: the intervention of the military regarding the institution of a democracy, and the sabotage by the same military leading it to its demise. In addition to this, to the people of Pakistan, the military has retained the impression that the government is incapable of maintaining a productive and functioning state, and is incompetent in its executing of pertaining affairs. The role of the military in Pakistani politics has hindered any hope of the country implementing a stable democracy. To say the least, the relationship between the government and the resistance is a consistent struggle.[17]

The military has extended its role today with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. The involvement of the military has affected “four out of five key areas of civilian control”. Decision making was an area that was to be shared by the military and the people of Pakistan, but has since turned into an opportunity for the military to exercise its control due to the fact that CPEC is not only a “corporate mega project” but also a huge economic opportunity, and the military in Pakistan continues to be the leading force in the creation of the guidelines pertaining to national defense and internal security. Furthermore, accusations of corruption have not helped; the Panama Papers were “documents [exposing] the offshore holdings of 12 current and former world leaders.”[18] These findings further the belief that Pakistan’s leaders are incompetent and incapable of effectively governing the country, and giving the military more of a reason to continue and increase its interference. In consequence, the involvement of civilians in policy making is declining steadily, and little by little the military seeks to achieve complete autonomy from the government, and an increased partnership with China. It is safe to say that CPEC would have been an opportunity to improve military and civilian relationships, however it seems to be an opportunity lost as it appears the military is creating a government capable of functioning as a legitimate operation.[19]

[1] Gottmann, J., & Fox, E. W. (1973). History in Geographic Perspective: The Other France. Geographical Review.

[2] Tariq Ali (2009). The Duel: Pakistan on the Flight Path of American Power

[3] Marquina, A. (2010). La Política de Seguridad y Defensa de la Unión Europea. 28, 441–446.

[4] Tariq Ali (2009). Ibíd.

[5] Sánchez de Rojas Díaz, E. (2016). ¿Es Paquistán uno de los países más conflictivos del mundo? Los orígenes del terrorismo en Paquistán.

[6] Ríos, X. (2020). India se alinea con EE.UU.

[7] Economic corridor: China to extend assistance at 1.6 percent interest rate. (2015). Business Recorder.

[8] Szczepanski, Kallie. "Pakistan | Facts and History." ThoughtCo.

[9] Pakistan Insider. “Pakistan's Geography, Climate, and Environment.” Pakistan Insider, February 9, 2012.

[10] Burki, Shahid Javed, and Lawrence Ziring. “Pakistan.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., March 6, 2020.

[11] Mustafa, Daanish, Nausheen Anwar, and Amiera Sawas. “Gender, Global Terror, and Everyday Violence in Urban Pakistan.” Elsevier. Elsevier Ltd., December 4, 2018

[12] Bhattacharjee, Dhrubajyoti. “China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).” Indian Council of World Affairs, May 12, 2015

[13] Burki, Shahid Javed, and Lawrence Ziring. Ibíd.

[14] IMF, “Economic Outlook”, October 2019.

[15] IMF, “World Economic Outlook”, April 2020.

[16] Wolf, Siegfried O. “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, Civil-Military Relations and Democracy in Pakistan.” SADF Working Paper, no. 2 (September 13, 2016)

[17] Ibíd.

[18] “Giant Leak of Offshore Financial Records Exposes Global Array of Crime and Corruption.” The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, April 3, 2016.

[19] Wolf, Siegfried O. Ibíd.

[Myra MacDonald, Defeat is an Orphan. How Pakistan Lost the Great South Asia War. Penguin. London, 2016. 313 p.]

RESEÑA / Ramón Barba

Podría pensarse que el libro de Myra McDonald más bien confunde al lector, por cuanto el título habla de una Gran Guerra en el subcontinente indio de la que como tal no existe constancia. En realidad, la obra ayuda a entender –especialmente al lector occidental, más alejado del marco cultural e histórico de esa parte del mundo– la complejidad de las relaciones entre India y Pakistán. Corresponsal de Reuters durante más de treinta años, con larga experiencia en la región, McDonald sabe sumar datos concretos, sin quedarse en la anécdota, e ir rápidamente a la fuerza de fondo que hay detrás de ellos.

Podría pensarse que el libro de Myra McDonald más bien confunde al lector, por cuanto el título habla de una Gran Guerra en el subcontinente indio de la que como tal no existe constancia. En realidad, la obra ayuda a entender –especialmente al lector occidental, más alejado del marco cultural e histórico de esa parte del mundo– la complejidad de las relaciones entre India y Pakistán. Corresponsal de Reuters durante más de treinta años, con larga experiencia en la región, McDonald sabe sumar datos concretos, sin quedarse en la anécdota, e ir rápidamente a la fuerza de fondo que hay detrás de ellos.

Su tesis es que desde que nacieron los dos Estados con la partición de la Joya de la Corona, al deshacerse el Imperio Británico, paquistaníes e indios han protagonizado una larga confrontación, que incluso ha tenido sus momentos de fuego real. Ha sido una prolongada y enconada enemistad entre los dos países, con sus esporádicas batallas: una Gran Guerra, según la autora, que finalmente Pakistán ha perdido.

Por lo general, mientras que India ha buscado su afirmación nacional en el ejercicio de la democracia, Pakistán ha basado su idiosincrasia nacional en el Islam y en el conflicto con India, el cual tiene en la disputa por el control de Cachemira su manifestación más sangrienta. Esa fijación con India, de acuerdo con McDonald, ha llevado a Islamabad a valerse del apoyo a grupos yihadistas para crear inestabilidad al otro lado de la línea de partición, hundiéndose el propio Pakistán en un abismo del que por ahora no ha conseguido salir. McDonald sigue una argumentación generalmente objetiva, pero el libro parece estar escrito desde India, sin apenas simpatía por los paquistaníes.

El relato arranca con el episodio del secuestro del avión de Indian Airlines que tuvo lugar entre Nochebuena y Nochevieja de 1999 por parte de cinco guerrilleros cachemires, con 155 personas a bordo, y que supuso un serio conflicto entre Islamabad y Nueva Delhi, al interpretar el Gobierno indio que la operación había contado con cierto respaldo del país vecino. El episodio sirve para describir los dramáticos estándares de la pugna estratégica entre los dos países, que el año anterior culminaron su desarrollo de la bomba atómica.

El libro presta especial atención a esa carrera por lograr el arma nuclear –los indios porque los chinos la tenían, los paquistaníes porque veían que los indios la estaban alcanzando– y que venía a plantear una duda clave de la proliferación nuclear: ¿cabe el uso de las armas a menor escala entre dos países mortalmente enemigos cuando ambos disponen de la bomba atómica? Se ha visto que sí, y no solo eso, argumenta McDonald: la falta de miedo de Pakistán a un ataque indio nuclear, dado que este se ve disuadido por el propio arsenal paquistaní, habría hecho que Islamabad se viera más confiada a la hora de alentar ataques terroristas contra India.

A principios de la década de 1960 la situación en India era un tanto delicada: en 1964 China había detonado la bomba atómica, lo cual aunado a la presión paquistaní en Cachemira ponía a la mayor democracia del mundo en una complicada coyuntura. Ello dio lugar al lanzamiento por parte de India del Smiling Buddha en 1974 (como bomba sin carga) y al inicio de una estrecha competición con Pakistán por entrar en el reducido club nuclear, como consecuencia de la lógica dialéctica que entonces regía su relación. Aunque se creía que la bomba podía estar en el haber de una de las partes, no fue hasta las tardías detonaciones de 1998 que ello quedó patente.

La autora considera que los dos países llegaron ese año en un nivel muy parejo: India, más grande, tenía que solventar pequeñas crisis internas para poder avanzar, mientras que Pakistán gozaba de cierta estabilidad. No obstante, la consecución de la bomba atómica hizo que Pakistán, tras una mala lectura de la realidad, no supiese aprovechar sus oportunidades en la etapa de la globalización que entonces se abría, y se quedase estancado en una lógica belicista, mientras India daba el estirón que le ha hecho ganar un indudable peso como potencia mundial. Esa es la “derrota” paquistaní de la que habla el título de la obra.

Además de esa atención a las décadas más recientes, el texto también se retrotrae a 1947, cuando nacieron ambos estados independientes, para explicar muchas de las dinámicas de la subsiguiente relación entre ambos. Asimismo se abordan las relaciones con China, aliada de Pakistán, y con Estados Unidos, que tuvo más cercanía de intereses con Pakistán y ahora es más próximo a India.