Breadcrumb

Blogs

Entries with Categorías Global Affairs Análisis .

The struggle for power has already started in the Islamic Republic in the midst of US sanctions and ahead a new electoral cycle

![Ayatollah Ali Khamenei speaking to Iranian Air Force personnel, in 2016 [Wikipedia] Ayatollah Ali Khamenei speaking to Iranian Air Force personnel, in 2016 [Wikipedia]](/documents/10174/16849987/khamenei-blog.jpg)

▲ Ayatollah Ali Khamenei speaking to Iranian Air Force personnel, in 2016 [Wikipedia]

ANALYSIS / Rossina Funes and Maeve Gladin

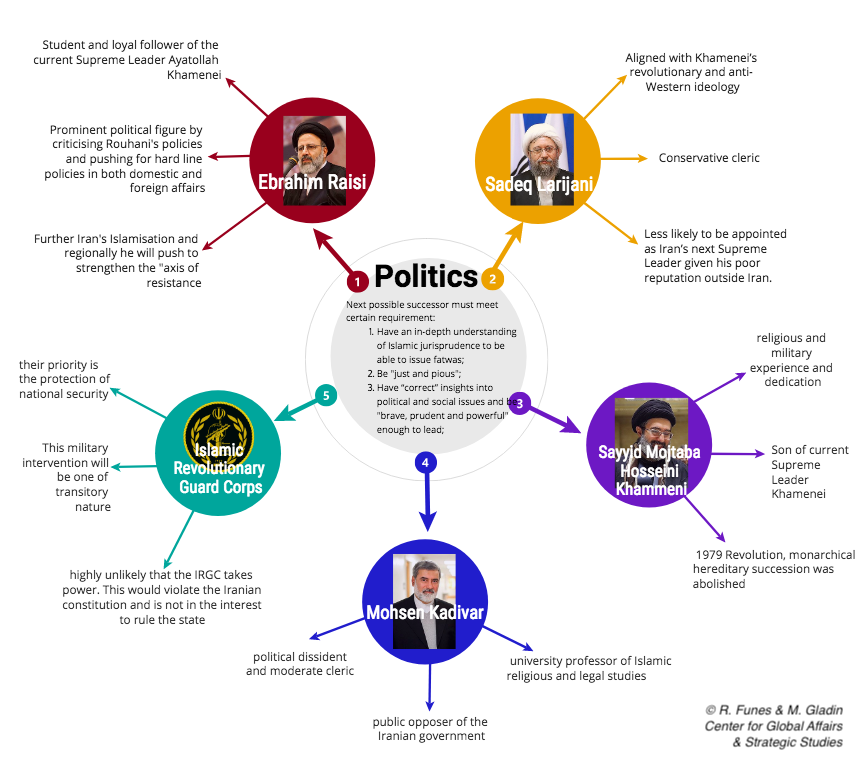

The failing health of Supreme Leader Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei, 89, brings into question the political aftermath of his approaching death or possible step-down. Khamenei’s health has been a point of query since 2007, when he temporarily disappeared from the public eye. News later came out that he had a routine procedure which had no need to cause any suspicions in regards to his health. However, the question remains as to whether his well-being is a fantasy or a reality. Regardless of the truth of his health, many suspect that he has been suffering prostate cancer all this time. Khamenei is 89 years old –he turns 80 in July– and the odds of him continuing as active Supreme Leader are slim to none. His death or resignation will not only reshape but could also greatly polarize the successive politics at play and create more instability for Iran.

The next possible successor must meet certain requirements in order to be within the bounds of possible appointees. This political figure must comply and follow Khamenei’s revolutionary ideology by being anti-Western, mainly anti-American. The prospective leader would also need to meet religious statues and adherence to clerical rule. Regardless of who that cleric may be, Iran is likely to be ruled by another religious figure who is far less powerful than Khamenei and more beholden to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Additionally, Khamenei’s successor should be young enough to undermine the current opposition to clerical rule prevalent among many of Iran’s youth, which accounts for the majority of Iran’s population.

In analyzing who will head Iranian politics, two streams have been identified. These are constrained by whether the current Supreme Leader Khamenei appoints his successor or not, and within that there are best and worst case scenarios.

Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi

Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi had been mentioned as the foremost contender to stand in lieu of Iranian Supreme Leader Khamenei. Shahroudi was a Khamenei loyalist who rose to the highest ranks of the Islamic Republic’s political clerical elite under the supreme leader’s patronage and was considered his most likely successor. A former judiciary chief, Shahroudi was, like his patron, a staunch defender of the Islamic Revolution and its founding principle, velayat-e-faqih (rule of the jurisprudence). Iran’s domestic unrest and regime longevity, progressively aroused by impromptu protests around the country over the past year, is contingent on the political class collectively agreeing on a supreme leader competent of building consensus and balancing competing interests. Shahroudi’s exceptional faculty to bridge the separated Iranian political and clerical establishment was the reason his name was frequently highlighted as Khamenei’s eventual successor. Also, he was both theologically and managerially qualified and among the few relatively nonelderly clerics viewed as politically trustworthy by Iran’s ruling establishment. However, he passed away in late December 2018, opening once again the question of who was most likely to take Khamenei’s place as Supreme Leader of Iran.

However, even with Shahroudi’s early death, there are still a few possibilities. One is Sadeq Larijani, the head of the judiciary, who, like Shahroudi, is Iraqi born. Another prospect is Ebrahim Raisi, a former 2017 presidential candidate and the custodian of the holiest shrine in Iran, Imam Reza. Raisi is a student and loyalist of Khamenei, whereas Larijani, also a hard-liner, is more independent.

1. MOST LIKELY SCENARIO, REGARDLESS OF APPOINTMENT

1.1 Ebrahim Raisi

In a more likely scenario, Ebrahim Raisi would rise as Iran’s next Supreme Leader. He meets the requirements aforementioned with regards to the religious status and the revolutionary ideology. Fifty-eight-years-old, Raisi is a student and loyal follower of the current Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei. Like his teacher, he is from Mashhad and belongs to its famous seminary. He is married to the daughter of Ayatollah Alamolhoda, a hardline cleric who serves as Khamenei's representative of in the eastern Razavi Khorasan province, home of the Imam Reza shrine.

Together with his various senior judicial positions, in 2016 Raisi was appointed the chairman of Astan Quds Razavi, the wealthy and influential charitable foundation which manages the Imam Reza shrine. Through this appointment, Raisi developed a very close relationship with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which is a known ideological and economic partner of the foundation. In 2017, he moved into the political sphere by running for president, stating it was his "religious and revolutionary responsibility". He managed to secure a respectable 38 percent of the vote; however, his contender, Rouhani, won with 57 percent of the vote. At first, this outcome was perceived as an indicator of Raisi’s relative unpopularity, but he has proven his detractors wrong. After his electoral defeat, he remained in the public eye and became an even more prominent political figure by criticizing Rouhani's policies and pushing for hard-line policies in both domestic and foreign affairs. Also, given to Astan Quds Foundation’s extensive budget, Raisi has been able to secure alliances with other clerics and build a broad network that has the ability to mobilize advocates countrywide.

Once he takes on the role of Supreme Leader, he will continue his domestic and regional policies. On the domestic front, he will further Iran's Islamisation and regionally he will push to strengthen the "axis of resistance", which is the anti-Western and anti-Israeli alliance between Iran, Syria, Hezbollah, Shia Iraq and Hamas. Nevertheless, if this happens, Iran would live on under the leadership of yet another hardliner and the political scene would not change much. Regardless of who succeeds Khamenei, a political crisis is assured during this transition, triggered by a cycle of arbitrary rule, chaos, violence and social unrest in Iran. It will be a period of uncertainty given that a great share of the population seems unsatisfied with the clerical establishment, which was also enhanced by the current economic crisis ensued by the American sanctions.

1.2 Sadeq Larijani

Sadeq Larijani, who is fifty-eight years old, is known for his conservative politics and his closeness to the supreme guide of the Iranian regime Ali Khamenei and one of his potential successors. He is Shahroudi’s successor as head of the judiciary and currently chairs the Expediency Council. Additionally, the Larijani family occupies a number of important positions in government and shares strong ties with the Supreme Leader by being among the most powerful families in Iran since Khamenei became Supreme Leader thirty years ago. Sadeq Larijani is also a member of the Guardian Council, which vetos laws and candidates for elected office for conformance to Iran’s Islamic system.

Formally, the Expediency Council is an advisory body for the Supreme Leader and is intended to resolve disputes between parliament and a scrutineer body, therefore Larijani is well informed on the way Khamenei deals with governmental affairs and the domestic politics of Iran. Therefore, he meets the requirement of being aligned with Khamenei’s revolutionary and anti- Western ideology, and he is also a conservative cleric, thus he complies with the religious figure requirement. Nonetheless, he is less likely to be appointed as Iran’s next Supreme Leader given his poor reputation outside Iran. The U.S. sanctioned Larijani on the grounds of human rights violations, in addition to “arbitrary arrests of political prisoners, human rights defenders and minorities” which “increased markedly” since he took office, according to the EU who also sanctioned Larijani in 2012. His appointment would not be a strategic decision amidst the newly U.S. imposed sanctions and the trouble it has brought upon Iran. Nowadays, the last thing Iran wants is that the EU also turn their back to them, which would happen if Larijani rises to power. However it is still highly plausible that Larijani would be the second one on the list of prospective leaders, only preceded by Raisi.

|

2. LEAST LIKELY SCENARIO: SUCCESSOR NOT APPOINTED

2.1 Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

The IRGC’s purpose is to preserve the Islamic system from foreign interference and protect from coups. As their priority is the protection of national security, the IRGC necessarily will take action once Khamenei passes away and the political sphere becomes chaotic. In carrying out their role of protecting national security, the IRGC will act as a support for the new Supreme Leader. Moreover, the IRGC will work to stabilize the unrest which will inevitably occur, regardless of who comes to power. It is our estimate that the new Supreme Leader will have been appointed by Khamenei before death, and thus the IRGC will do all in their power to protect him. In the unlikely case that Khamenei does not appoint a successor, we believe that there are two unlikely options of ruling that could arise.

The first, and least likely, being that the IRGC takes rule. Moreover, it is highly unlikely that the IRGC takes power. This would violate the Iranian constitution and is not in the interest to rule the state. What they are interested in is having a puppet figure who will satisfy their interests. As the IRGC's main role is national security, in the event that Khamenei does not appoint a successor and the country goes into political and social turmoil, the IRGC will without a doubt step in. This military intervention will be one of transitory nature, as the IRGC does not pretend to want direct political power. Once the Supreme Leader is secured, the IRGC will go back to a relatively low profile.

In the very unlikely event that a Supreme Leader is not predetermined, the IRGC may take over the political regime of Iran, creating a military dictatorship. If this were to happen, there would certainly be protests, riots and coups. It would be very difficult for an opposition group to challenge and defeat the IRGC, but there would be attempts to overcome it. This would be a regime of temporary nature, however, the new Supreme Leader would arise from the scene that the IRGC had been protecting.

2.2 Mohsen Kadivar

In addition, political dissident and moderate cleric Mohsen Kadivar is a plausible candidate for the next Supreme Leader. Kadivar’s rise to political power in Iran would be a black swan, as it is extremely unlikely, however, the possibility should not be dismissed. His election would be highly unlikely due to the fact that he is a vocal critic of clerical rule and has been a public opposer of the Iranian government. He has served time in prison for speaking out in favor of democracy and liberal reform as well as publicly criticizing the Islamic political system. Moreover, he has been a university professor of Islamic religious and legal studies throughout the United States. As Kadivar goes against all requirements to become successor, he is highly unlikely to become Supreme Leader. It is also important to keep in mind that Khamenei will most likely appoint a successor, and in that scenario, he will appoint someone who meets the requirements and of course is in line with what he believes. In the rare case that Khamenei does not appoint a successor or dies before he gets the chance to, a political uprising is inevitable. The question will be whether the country uprises to the point of voting a popular leader or settling with someone who will maintain the status quo.

In the situation that Mohsen Kadivar is voted into power, the Iranian political system would change drastically. For starters, he would not call himself Supreme Leader, and would instill a democratic and liberal political system. Kadivar and other scholars which condemn supreme clerical rule are anti-despotism and advocate for its abolishment. He would most likely establish a western-style democracy and work towards stabilizing the political situation of Iran. This would take more years than he will allow himself to remain in power, however, he will probably stay active in the political sphere both domestically as well as internationally. He may be secretary of state after stepping down, and work as both a close friend and advisor of the next leader of Iran as well as work for cultivating ties with other democratic countries.

2.3 Sayyid Mojtaba Hosseini Khamenei

Khamenei's son, Sayyid Mojtaba Hosseini Khamenei is also rumored to be a possible designated successor. His religious and military experience and dedication, along with being the son of Khamenei gives strong reason to believe that he may be appointed Supreme Leader by his father. However, Mojtaba is lacking the required religious status. The requirements of commitment to the IRGC as well as anti-American ideology are not questioned, as Mojtaba has a well-known strong relationship with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Mojtaba studied theology and is currently a professor at Qom Seminary in Iran. Nonetheless, it is unclear as to whether Mojtaba’s religious and political status is enough to have him considered to be the next Supreme Leader. In the improbable case that Khamenei names his son to be his successor, it would be possible for his son to further commit to the religious and political facets of his life and align them with the requirements of being Supreme Leader.

This scenario is highly unlikely, especially considering that in the 1979 Revolution, monarchical hereditary succession was abolished. Mojtaba has already shown loyalty to Iran when taking control of the Basij militia during the uproar of the 2009 elections to halt protests. While Mojtaba is currently not fit for the position, he is clearly capable of gaining the needed credentials to live up to the job. Despite his potential, all signs point to another candidate becoming the successor before Mojtaba.

3. PATH TO DEMOCRACY

Albeit the current regime is supposedly overturned by an uprising or new appointment by the current Supreme Leader Khamenei, it is expected that any transition to democracy or to Western-like regime will take a longer and more arduous process. If this was the case, it will be probably preceded by a turmoil analogous to the Arab Springs of 2011. However, even if there was a scream for democracy coming from the Iranian population, the probability that it ends up in success like it did in Tunisia is slim to none. Changing the president or the Supreme Leader does not mean that the regime will also change, but there are more intertwined factors that lead to a massive change in the political sphere, like it is the path to democracy in a Muslim state.

▲ Protest in London in October 2018 after the disappearance of Jamal Khashoggi [John Lubbock, Wikimedia Commons]

ANALYSIS / Naomi Moreno Cosgrove

October 2nd last year was the last time Jamal Khashoggi—a well-known journalist and critic of the Saudi government—was seen alive. The Saudi writer, United States resident and Washington Post columnist, had entered the Saudi consulate in the Turkish city of Istanbul with the aim of obtaining documentation that would certify he had divorced his previous wife, so he could remarry; but never left.

After weeks of divulging bits of information, the Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, laid out his first detailed account of the killing of the dissident journalist inside the Saudi Consulate. Eighteen days after Khashoggi disappeared, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) acknowledged that the 59-year-old writer had died after his disappearance, revealing in their investigation findings that Jamal Khashoggi died after an apparent “fist-fight” inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul; but findings were not reliable. Resultantly, the acknowledgement by the KSA of the killing in its own consulate seemed to pose more questions than answers.

Eventually, after weeks of repeated denials that it had anything to do with his disappearance, the contradictory scenes, which were the latest twists in the “fast-moving saga”, forced the kingdom to eventually acknowledge that indeed it was Saudi officials who were behind the gruesome murder thus damaging the image of the kingdom and its 33-year-old crown prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS). What had happened was that the culmination of these events, including more than a dozen Saudi officials who reportedly flew into Istanbul and entered the consulate just before Khashoggi was there, left many sceptics wondering how it was possible for MBS to not know. Hence, the world now casts doubt on the KSA’s explanation over Khashoggi’s death, especially when it comes to the shifting explanations and MBS’ role in the conspiracy.

As follows, the aim of this study is to examine the backlash Saudi Arabia’s alleged guilt has caused, in particular, regarding European state-of-affairs towards the Middle East country. To that end, I will analyse various actions taken by European countries which have engaged in the matter and the different modus operandi these have carried out in order to reject a bloodshed in which arms selling to the kingdom has become the key issue.

Since Khashoggi went missing and while Turkey promised it would expose the “naked truth” about what happened in the Saudi consulate, Western countries had been putting pressure on the KSA for it to provide facts about its ambiguous account on the journalist’s death. In a joint statement released on Sunday 21st October 2018, the United Kingdom, France and Germany said: “There remains an urgent need for clarification of exactly what happened on 2nd October – beyond the hypotheses that have been raised so far in the Saudi investigation, which need to be backed by facts to be considered credible.” What happened after the kingdom eventually revealed the truth behind the murder, was a rather different backlash. In fact, regarding post-truth reactions amongst European countries, rather divergent responses have occurred.

Terminating arms selling exports to the KSA had already been carried out by a number of countries since the kingdom launched airstrikes on Yemen in 2015; a conflict that has driven much of Yemen’s population to be victims of an atrocious famine. The truth is that arms acquisition is crucial for the KSA, one of the world’s biggest weapons importers which is heading a military coalition in order to fight a proxy war in which tens of thousands of people have died, causing a major humanitarian catastrophe. In this context, calls for more constraints have been growing particularly in Europe since the killing of the dissident journalist. These countries, which now demand transparent clarifications in contrast to the opacity in the kingdom’s already-given explanations, are threatening the KSA with suspending military supply to the kingdom.

COUNTRIES THAT HAVE CEASED ARMS SELLING

Germany

Probably one of the best examples with regards to the ceasing of arms selling—after not been pleased with Saudi state of affairs—is Germany. Following the acknowledgement of what happened to Khashoggi, German Chancellor Angela Merkel declared in a statement that she condemned his death with total sharpness, thus calling for transparency in the context of the situation, and stating that her government halted previously approved arms exports thus leaving open what would happen with those already authorised contracts, and that it wouldn’t approve any new weapons exports to the KSA: “I agree with all those who say that the, albeit already limited, arms export can’t take place in the current circumstances,” she said at a news conference.

So far this year, the KSA was the second largest customer in the German defence industry just after Algeria, as until September last year, the German federal government allocated export licenses of arms exports to the kingdom worth 416.4 million euros. Respectively, according to German Foreign Affair Minister, Heiko Maas, Germany was the fourth largest exporter of weapons to the KSA.

This is not the first time the German government has made such a vow. A clause exists in the coalition agreement signed by Germany’s governing parties earlier in 2018 which stated that no weapons exports may be approved to any country “directly” involved in the Yemeni conflict in response to the kingdom’s countless airstrikes carried out against Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in the area for several years. Yet, what is clear is that after Khashoggi’s murder, the coalition’s agreement has been exacerbated. Adding to this military sanction Germany went even further and proposed explicit sanctions to the Saudi authorities who were directly linked to the killing. As follows, by stating that “there are more questions unanswered than answered,” Maas declared that Germany has issued the ban for entering Europe’s border-free Schengen zone—in close coordination with France and Britain—against the 18 Saudi nationals who are “allegedly connected to this crime.”

Following the decision, Germany has thus become the first major US ally to challenge future arms sales in the light of Khashoggi’s case and there is thus a high likelihood that this deal suspension puts pressure on other exporters to carry out the same approach in the light of Germany’s Economy Minister, Peter Altmaier’s, call on other European Union members to take similar action, arguing that “Germany acting alone would limit the message to Riyadh.”

Norway

Following the line of the latter claim, on November 9th last year, Norway became the first country to back Germany’s decision when it announced it would freeze new licenses for arms exports to the KSA. Resultantly, in her statement, Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ine Eriksen Søreide, declared that the government had decided that in the present situation they will not give new licenses for the export of defence material or multipurpose good for military use to Saudi Arabia. According to the Søreide, this decision was taken after “a broad assessment of recent developments in Saudi Arabia and the unclear situation in Yemen.” Although Norwegian ministry spokesman declined to say whether the decision was partly motivated by the murder of the Saudi journalist, not surprisingly, Norway’s announcement came a week after its foreign minister called the Saudi ambassador to Oslo with the aim of condemning Khashoggi’s assassination. As a result, the latter seems to imply Norway’s motivations were a mix of both; the Yemeni conflict and Khashoggi’s death.

Denmark and Finland

By following a similar decision made by neighbouring Germany and Norway—despite the fact that US President Trump backed MBS, although the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had assessed that the crown prince was responsible for the order of the killing—Denmark and Finland both announced that they would also stop exporting arms to the KSA.

Emphasising on the fact that they were “now in a new situation”—after the continued deterioration of the already terrible situation in Yemen and the killing of the Saudi journalist—Danish Foreign Minister, Anders Samuelsen, stated that Denmark would proceed to cease military exports to the KSA remarking that Denmark already had very restrictive practices in this area and hoped that this decision would be able to create a “further momentum and get more European Union (EU) countries involved in the conquest to support tight implementation of the Union’s regulatory framework in this area.”

Although this ban is still less expansive compared to German measures—which include the cancelation of deals that had already been approved—Denmark’s cease of goods’ exports will likely crumble the kingdom’s strategy, especially when it comes to technology. Danish exports to the KSA, which were mainly used for both military and civilian purposes, are chiefly from BAE Systems Applied Intelligence, a subsidiary of the United Kingdom’s BAE Systems, which sold technology that allowed Intellectual Property surveillance and data analysis for use in national security and investigation of serious crimes. The suspension thus includes some dual-use technologies, a reference to materials that were purposely thought to have military applications in favour of the KSA.

On the same day Denmark carried out its decision, Finland announced they were also determined to halt arms export to Saudi Arabia. Yet, in contrast to Norway’s approach, Finnish Prime Minister, Juha Sipilä, held that, of course, the situation in Yemen lead to the decision, but that Khashoggi’s killing was “entirely behind the overall rationale”.

Finnish arms exports to the KSA accounted for 5.3 million euros in 2017. Nevertheless, by describing the situation in Yemen as “catastrophic”, Sipilä declared that any existing licenses (in the region) are old, and in these circumstances, Finland would refuse to be able to grant updated ones. Although, unlike Germany, Helsinki’s decision does not revoke existing arms licenses to the kingdom, the Nordic country has emphasized the fact that it aims to comply with the EU’s arms export criteria, which takes particular account of human rights and the protection of regional peace, security and stability, thus casting doubt on the other European neighbours which, through a sense of incoherence, have not attained to these values.

European Parliament

Speaking in supranational terms, the European Parliament agreed with the latter countries and summoned EU members to freeze arms sales to the kingdom in the conquest of putting pressure on member states to emulate the Germany’s decision.

By claiming that arms exports to Saudi Arabia were breaching international humanitarian law in Yemen, the European Parliament called for sanctions on those countries that refuse to respect EU rules on weapons sales. In fact, the latest attempt in a string of actions compelling EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini to dictate an embargo against the KSA, including a letter signed by MEPs from several parties.

Rapporteur for a European Parliament report on EU arms exports, Bodil Valero said: "European weapons are contributing to human rights abuses and forced migration, which are completely at odds with the EU's common values." As a matter of fact, two successful European Parliament resolutions have hitherto been admitted, but its advocates predicted that some member states especially those who share close trading ties with the kingdom are deep-seated, may be less likely to cooperate. Fact that has eventually occurred.

COUNTRIES THAT HAVE NOT CEASED ARMS SELLING

France

In contrast to the previously mentioned countries, other European states such as France, UK and Spain, have approached the issue differently and have signalled that they will continue “business as usual”.

Both France and the KSA have been sharing close diplomatic and commercial relations ranging from finance to weapons. Up to now, France relished the KSA, which is a bastion against Iranian significance in the Middle East region. Nevertheless, regarding the recent circumstances, Paris now faces a daunting challenge.

Just like other countries, France Foreign Minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, announced France condemned the killing “in the strongest terms” and demanded an exhaustive investigation. "The confirmation of Mr. Jamal Khashoggi's death is a first step toward the establishment of the truth. However, many questions remain unanswered," he added. Following this line, France backed Germany when sanctioning the 18 Saudi citizens thus mulling a joint ban from the wider visa-free Schengen zone. Nevertheless, while German minister Altmeier summoned other European countries to stop selling arms to Riyadh—until the Saudi authorities gave the true explanation on Khashoggi’s death—, France refused to report whether it would suspend arms exports to the KSA. “We want Saudi Arabia to reveal all the truth with full clarity and then we will see what we can do,” he told in a news conference.

In this context, Amnesty International France has become one of Paris’ biggest burdens. The organization has been putting pressure on the French government for it to freeze arms sales to the realm. Hence, by acknowledging France is one of the five biggest arms exporters to Riyadh—similar to the Unites States and Britain—Amnesty International France is becoming aware France’s withdrawal from the arms sales deals is crucial in order to look at the Yemeni conflict in the lens of human rights rather than from a non-humanitarian-geopolitical perspective. Meanwhile, France tries to justify its inaction. When ministry deputy spokesman Oliver Gauvin was asked whether Paris would mirror Berlin’s actions, he emphasized the fact that France’s arms sales control policy was meticulous and based on case-by-case analysis by an inter-ministerial committee. According to French Defence Minister Florence Parly, France exported 11 billion euros worth of arms to the kingdom from 2008 to 2017, fact that boosted French jobs. In 2017 alone, licenses conceivably worth 14.7 billion euros were authorized. Moreover, she went on stating that those arms exports take into consideration numerous criteria among which is the nature of exported materials, the respect of human rights, and the preservation of peace and regional security. "More and more, our industrial and defence sectors need these arms exports. And so, we cannot ignore the impact that all of this has on our defence industry and our jobs," she added. As a result, despite President Emmanuel Macron has publicly sought to devalue the significance relations with the KSA have, minister Parly, seemed to suggest the complete opposite.

Anonymously, a government minister held it was central that MBS retained his position. “The challenge is not to lose MBS, even if he is not a choir boy. A loss of influence in the region would cost us much more than the lack of arms sales”. Notwithstanding France’s ambiguity, Paris’ inconclusive attitude is indicating France’s clout in the region is facing a vulnerable phase. As president Macron told MBS at a side-line G20 summit conversation in December last year, he is worried. Although the context of this chat remains unclear, many believe Macron’s intentions were to persuade MBS to be more transparent as a means to not worsen the kingdom’s reputation and thus to, potentially, dismantle France´s bad image.

United Kingdom

As it was previously mentioned, the United Kingdom took part in the joint statement carried out also by France and Germany through its foreign ministers which claimed there was a need for further explanations regarding Khashoggi’s killing. Yet, although Britain’s Foreign Office said it was considering its “next steps” following the KSA’s admission over Khashoggi’s killing, UK seems to be taking a rather similar approach to France—but not Germany—regarding the situation.

In 2017, the UK was the sixth-biggest arms dealer in the world, and the second-largest exporter of arms to the KSA, behind the US. This is held to be a reflection of a large spear in sales last year. After the KSA intervened in the civil war in Yemen in early 2015, the UK approved more than 3.5billion euros in military sales to the kingdom between April 2015 and September 2016.

As a result, Theresa May has been under pressure for years to interrupt arms sales to the KSA specially after human rights advocates claimed the UK was contributing to alleged violations of international humanitarian law by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen. Adding to this, in 2016, a leaked parliamentary committee report suggested that it was likely that British weapons had been used by the Saudi-led coalition to violate international law, and that manufactured aircraft by BAE Systems, have been used in combat missions in Yemen.

Lately, in the context of Khashoggi’s death things have aggravated and the UK is now facing a great amount of pressure, mainly embodied by UK’s main opposition Labour party which calls for a complete cease in its arms exports to the KSA. In addition, in terms of a more international strain, the European Union has also got to have a say in the matter. Philippe Lamberts, the Belgian leader of the Green grouping of parties, said that Brexit should not be an excuse for the UK to abdicate on its moral responsibilities and that Theresa May had to prove that she was keen on standing up to the kind of atrocious behaviour shown by the killing of Khashoggi and hence freeze arms sales to Saudi Arabia immediately.

Nonetheless, in response and laying emphasis on the importance the upholding relation with UK’s key ally in the Middle East has, London has often been declining calls to end arms exports to the KSA. Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt defended there will be “consequences to the relationship with Saudi Arabia” after the killing of Khashoggi, but he has also pointed out that the UK has an important strategic relationship with Riyadh which needs to be preserved. As a matter of fact, according to some experts, UK’s impending exit from the EU has played a key role. The Campaign Against Arms Trade (CAAT) claims Theresa May’s pursuit for post-Brexit trade deals has seen an unwelcome focus on selling arms to some of the world's most repressive regimes. Nevertheless, by thus tackling the situation in a similar way to France, the UK justifies its actions by saying that it has one of the most meticulous permitting procedures in the world by remarking that its deals comprehend safeguards that counter improper uses.

Spain

After Saudi Arabia’s gave its version for Khashoggi’s killing, the Spanish government said it was “dismayed” and echoed Antonio Guterres’ call for a thorough and transparent investigation to bring justice to all of those responsible for the killing. Yet, despite the clamour that arose after the murder of the columnist, just like France and the UK, Spain’s Prime Minister, Pedro Sánchez, defended arms exporting to the KSA by claiming it was in Spain’s interest to keep selling military tools to Riyadh. Sanchez held he stood in favour of Spain’s interests, namely jobs in strategic sectors that have been badly affected by “the drama that is unemployment". Thusly, proclaiming Spain’s unwillingness to freeze arms exports to the kingdom. In addition, even before Khashoggi’s killing, Sanchez's government was subject to many critics after having decided to proceed with the exporting of 400 laser-guided bombs to Saudi Arabia, despite worries that they could harm civilians in Yemen. Notwithstanding this, Sánchez justified Spain’s decision in that good ties with the Gulf state, a key commercial partner for Spain, needed to be kept.

As a matter of fact, Spain’s state-owned shipbuilder Navantia, in which 5,500 employees work, signed a deal in July last year which accounted for 1.8 billion euros that supplied the Gulf country with five navy ships. This shipbuilder is situated in the southern region of Andalusia, a socialist bulwark which accounts for Spain's highest unemployment estimates and which has recently held regional elections. Hence, it was of the socialist president’s interest to keep these constituencies pleased and the means to this was, of course, not interrupting arms deals with the KSA.

As a consequence, Spain has recently been ignoring the pressures that have arose from MEP’s and from Sanchez’s minorities in government—Catalan separatist parties and far-left party Podemos— which demand a cease in arms exporting. For the time being, Spain will continue business with the KSA as usual.

CONCLUSION

All things considered, while Saudi Arabia insists that MBS was not aware of the gruesome murder and is distracting the international attention towards more positive headlines—such as the appointment of the first female ambassador to the US—in order to clear the KSA’s image in the context of Khashoggi’s murder, several European countries have taken actions against the kingdom’s interests. Yet, the way each country has approached the matter has led to the rise of two separate blocks which are at discordance within Europe itself. Whereas some European leaders have shown a united front in casting blame on the Saudi government, others seem to express geopolitical interests are more important.

During the time Germany, Norway, Denmark and Finland are being celebrated by human rights advocates for following through on their threat to halt sales to the kingdom, bigger arms exporters—like those that have been analysed—have pointed out that the latter nations have far less to lose than they do. Nonetheless, inevitably, the ceasing carried out by the northern European countries which are rather small arms exporters in comparison to bigger players such as the UK and France, is likely to have exacerbated concerns within the European arms industry of a growing anti-Saudi consensus in the European Union or even beyond.

What is clear is that due to the impact Saudi Arabia’s state of affairs have caused, governments and even companies worldwide are coming under pressure to abandon their ties to the oil-rich, but at the same time, human-rights-violating Saudi Arabian leadership. Resultantly, in Europe, countries are taking part in two divergent blocks that are namely led by two of the EU’s most compelling members: France and Germany. These two sides are of rather distant opinions regarding the matter, fact that does not seem to be contributing in terms of the so-much-needed European Union integration.

ANÁLISIS / Nerea Álvarez

Las relaciones entre Japón y Corea no son fáciles. La anexión japonesa de la península en 1910 sigue muy presente en la memoria coreana. Por su parte, Japón posee un sentido de la historia distorsionado, fruto de haber asumido su culpabilidad en la guerra de modo obligado, forzado por el castigo sufrido en la Segunda Guerra Mundial y la ocupación estadounidense, y no como consecuencia de un proceso propio de asunción voluntaria de responsabilidades. Todo ello ha llevado a que Japón se resista a revisar su historia, sobretodo la de su época imperialista.

Uno elemento clave que dificulta una reconciliación sincera entre Japón y los países vecinos que se vieron invadidos por los nipones en la primera mitad del siglo XX son las mujeres de consuelo o “mujeres confort”. Este grupo de mujeres, procedentes de China, Filipinas, Myanmar, Taiwán, Indonesia, Tailandia, Malasia, Vietnam y Corea del Sur (alrededor del 80% provenían de este último país), son una consecuencia de la expansión de Japón comenzada en 1910. Durante este periodo, los soldados japoneses se llevaron aproximadamente entre 70.000 y 200.000 mujeres a estaciones de confort donde estos abusaban sexualmente de ellas. Estas estaciones siguieron en marcha en Japón hasta finales de los años 40. Según los testimonios de las mujeres supervivientes, los soldados japoneses se las llevaban de diversas formas: secuestro, engaño y extorsión son solo algunos ejemplos.

Según el testimonio de Kim Bok-Dong, una de las mujeres supervivientes, los soldados nipones adujeron que debían llevársela para trabajar en una fábrica de uniformes porque no tenían suficiente personal. En aquel entonces ella tenía 14 años. Los soldados prometieron a su madre devolvérsela una vez fuese mayor para casarse, y amenazaron con el exilio a toda la familia si no los padres no permitían la marcha de la joven. Fue transportada en ferri desde Busan hasta Shimonoseki (prefectura de Yamaguchi, en Japón), junto con otras treinta mujeres. Después tomaron otro barco que las transportó a Taiwán y luego a la provincia de Guangdong. Allí fueron recibidas por oficiales, que las acompañaron hasta el interior de un edificio donde les esperaban médicos. Examinaron sus cuerpos y las acompañaron a sus habitaciones. Las mujeres fueron agredidas y violadas repetidamente. Tras varias semanas, muchas pensaban en el suicidio: “Estábamos mucho mejor muertas” (Kim Bok-Dong, 2018). Muchas murieron debido a las condiciones a las que se les sometía, a causa de enfermedades, asesinadas por los soldados japoneses en los últimos años de la guerra o, si tenían oportunidad, suicidándose. Se estima que sobrevivieron alrededor de un cuarto o un tercio de las mujeres.

Largo proceso

Tras la guerra y pese a conocerse los hechos, ese dramático pasado fue quedando relegado en la historia, sin que se le prestara la atención necesaria. Corea del Sur no estaba preparada para ayudar a estas mujeres (y Corea del Norte había entrado en un absoluto aislamiento). Durante los años 60, las relaciones entre la República de Corea y Japón empeoraron debido a las políticas antijaponesas de los líderes políticos surcoreanos. En 1965, Tokio y Seúl firmaron el Tratado de Normalización, pero quedó demostrado que los asuntos económicos eran lo prioritario. Se tendieron puentes de cooperación entre ambos países, pero el conflicto emocional impedía y sigue impidiendo mayor relación en campos alejados del económico. Japón sigue alegando que en el Tratado de Normalización se encuentran los argumentos para descartar que estas mujeres posean el derecho de legitimación ante tribunales internacionales, aunque en el texto no se las mencione.

Las cosas comenzaron a cambiar en los años 70, cuando se formó en Japón la Asociación de las Mujeres Asiáticas, la cual empezó a arrojar luz sobre este aspecto de la historia reciente. Al principio, incluso el Gobierno coreano ignoró el problema. La razón principal fue la falta de pruebas de que los hechos hubieran ocurrido, ya que el Gobierno de Japón había mandado destruir los documentos comprometedores en 1945. Además, Japón impidió que el Gobierno surcoreano reclamara reparaciones adicionales por daños incurridos durante el período colonial basándose en el tratado de 1965.

La cultura del sudeste asiático jugó un papel importante en la ocultación de los hechos acontecidos. El valor de mantener las apariencias en la cultura oriental primaba sobre la denuncia de situaciones como las vividas por estas mujeres, que debieron callar durante décadas para no ser repudiadas por su familia.

Cuando la República de Corea se democratizó en 1987, el Gobierno surcoreano comenzó a darle importancia a esta cuestión. En 1990, el presidente Roh Tae Woo, pidió al Gobierno de Japón una lista con los nombres de las mujeres, pero la respuesta desde Tokio fue que esa información no existía porque los documentos se habían destruido. El dirigente socialista Motooka Shoji, miembro de la Cámara Alta de la Dieta japonesa, reclamó que se investigara lo ocurrido, pero el Parlamento alegó que el problema ya se habría resuelto con el Tratado de Normalización de 1965. En 1991, Kim Hak-Sun, una de las mujeres que sobrevivieron a la explotación sexual, presentó la primera demanda judicial, siendo la primera víctima en hablar de su experiencia. Esto supuso el arranque de la lucha de un grupo de más de cincuenta mujeres coreanas que pedían el reconocimiento de los hechos y una disculpa oficial del Gobierno japonés. A partir del 8 de enero de 1992, “todos los miércoles a las 12 del mediodía, las víctimas junto a miembros del Consejo Coreano y otros grupos sociales marchan frente a la Embajada de Japón en Seúl. La marcha consiste en levantar carteles exigiendo justicia y perdón y expresar en público sus reclamos”.

El Gobierno de Tokio negó toda implicación en el establecimiento, reclutamiento y estructuración del sistema de las mujeres de confort desde el principio. No obstante, desde la Secretaría del Gabinete tuvo que emitirse en 1992 una disculpa, aunque fue vaga y demasiado genérica, dirigida a todas las mujeres por los actos cometidos durante la guerra. No fue hasta ese año que el Gobierno japonés reconoció su implicación en la administración y supervisión de estas estaciones. La UNHRC determinó entonces que las acciones del Gobierno nipón representaban un crimen contra la humanidad que violó los derechos humanos de las mujeres asiáticas.

En 1993, Japón admitió haber reclutado bajo coerción a las mujeres coreanas. La coerción era la palabra clave para desmentir las declaraciones previas, que indicaban que estas mujeres se dedicaban a la prostitución voluntariamente. El secretario del Gabinete, Yohei Kono, declaró que “el ejército japonés estuvo, directa o indirectamente, involucrado en el establecimiento y la gestión de las estaciones de confort, y en el traslado de mujeres de confort... que, en muchos casos, fueron reclutados en contra de su propia voluntad”. El Gobierno de Japón ofreció sus disculpas, arrepintiéndose de lo sucedido, pero no hubo compensación a las víctimas. En 1994, la Comisión Internacional de Juristas recomendó a Japón pagar la cantidad de $40.000 a cada superviviente. El Gobierno quiso estructurar un plan para pagar a las mujeres con fondos no gubernamentales, pero el Consejo Coreano para las mujeres raptadas por Japón como exclavas sexuales, fundado en 1990 e integrado por 37 instituciones no se lo permitió.

En 1995, el primer ministro Murayama Tomiichi sentó las bases del Asian Women’s Fund, que serviría para proteger los derechos de las mujeres en Japón y en el mundo. A ojos internacionales, esta organización se vio como una excusa para escapar de las responsabilidades legales requeridas, ya que se recaudaba dinero público, lo que hacía que la participación del Gobierno fuese casi imperceptible. Además, comenzó a hacerse oír una creciente opinión minoritaria de ciudadanos afines a la derecha japonesa que calificaban a las mujeres confort de ‘prostitutas’, a las que no era necesario compensar de ningún modo.

No obstante, la compensación monetaria es una de las cuestiones que menos ha importado a este grupo de mujeres. Su prioridad ante todo es restaurar su dignidad. Que el Gobierno japonés no se haya implicado directamente y no acalle opiniones como las de la minoría derechista, es probablemente lo que más les afecte. Ante todo, estas mujeres luchan por que Tokio reconozca los hechos públicamente y ofrezca una disculpa oficial por lo ocurrido.

La ONU ha seguido tomando el papel de mediador a lo largo de los años. Encontramos en varios documentos pertenecientes a la UNHRC declaraciones que instan a Japón a resolver el problema. En un documento que revisa la primera demanda de la organización (2 de febrero de 1996) en el Consejo de los Derechos Humanos, figura la respuesta del primer ministro Ryutaro Hashimoto: “la cuestión acerca de las reparaciones se resolvió mediante tratados de paz y el Gobierno nunca pagará una indemnización a las víctimas”.

En el documento en cuestión, se clasifica de esclavitud militar a las estaciones de confort. Japón respondió negando cualquier tipo de responsabilidad legal, dada la incapacidad de aplicarse retroactivamente la ley internacional del momento, la imprecisión de la definición de estaciones de confort, la no vigencia de leyes contra la esclavitud durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial y la no prohibición en las leyes internacionales de cometer violaciones en situaciones de conflicto internacional. Además, adujo que las leyes existentes durante la guerra solo se podían aplicar a la conducta cometida por los militares japoneses contra ciudadanos de un Estado beligerante, pero no contra los ciudadanos de Corea, ya que esta fue anexionada y formaba parte del territorio japonés.

En 1998, la abogada estadounidense Gay J. McDougall presentó ante la UNHRC un documento que concluía que las acciones tomadas por las Fuerzas Armadas de Japón eran crímenes contra la humanidad. Más tarde, ese mismo año, la ONU adoptó el texto y cambió la definición previa a estaciones de violación.

|

Estatua de bronce de una “mujer de consuelo” frente a la embajada de Japón en Seúl [Wikipedia] |

Entendimiento que no llega

A lo largo de los años, el problema no ha hecho más que crecer y la política japonesa ha ido alejándose de un posible camino de mejora de las relaciones diplomáticas con sus vecinos. Este problema de revisión de la historia es la base de los movimientos políticos que observamos en Japón desde 1945. Las reformas impuestas por la ocupación estadounidense y los tribunales de Tokio jugaron un papel de gran importancia, así como el Tratado de San Francisco, firmado en 1948. Todo ello ha establecido en la población japonesa una aceptación pasiva de la historia pasada y de sus responsabilidades.

Al haber sido juzgados en los tribunales de 1948, la responsabilidad y culpabilidad que cargaban los nipones se creyó absuelta. Por otro lado, la ocupación de EEUU sobre el archipiélago, tomando el control militar, afectó al orgullo de los ciudadanos. La transformación de la economía, la política, la defensa y, sobretodo, la educación también tuvo sus repercusiones. Desde los comienzos democráticos de Japón, la política se ha centrado en una defensa pasiva, una educación antinacionalista y unas relaciones exteriores alineadas con los intereses de la potencia norteamericana.

Sin embargo, tras las elección como primer ministro en 2012 de Shinzo Abe, líder del Partido Liberal Democrático (LDP), se han introducido numerosos cambios en la política exterior e interior del país, con reformas en campos que van desde la economía hasta la educación y la defensa. Respecto a esta última, Abe se ha enfocado mayormente en reintroducir la fuerza militar en Japón a partir de una enmienda en el artículo 9 de la Constitución de 1945. Este giro se debe a la ideología propia del partido, que quiere dar a Japón un mayor peso en la política internacional. Uno de los puntos clave en su Gobierno es precisamente la postura frente al polémico tema de las mujeres confort.

En 2015, Shinzo Abe y la presidenta de la República de Corea, Park Geun-hye, firmaron un tratado en el que se establecían tres objetivos a cumplir: las disculpas oficiales de Japón, la donación de mil millones de yenes a una fundación surcoreana para el beneficio de estas mujeres y la retirada de la estatua en recuerdo de las mujeres confort levantada frente a la embajada de Japón en Seúl. Este tratado fue el mayor logro en el largo proceso del conflicto, y fue recibido como la solución a tantos años de disputa. Los dos primeros objetivos se cumplieron, pero la controvertida estatua no fue apartada de su emplazamiento. La llegada del presidente Moon Jae-in en 2017 complicó la completa implementación del acuerdo. Ese año, Moon criticó abiertamente el tratado, por considerar que deja de lado a las víctimas y al pueblo coreano en general. Su presidencia ha variado ciertos enfoques estratégicos de Corea del Sur y se desconoce exactamente qué quiere conseguir con Japón.

Acuerdo pendiente

Lo que sí puede concluirse es que retrasar la solución no es beneficioso para ninguna de las partes. Dejar el problema abierto está frustrando a todos los países involucrados, sobre todo a Japón. Un ejemplo de ello es la reciente ruptura de la hermandad entre las ciudades de San Francisco y Osaka en 2018 debido a una estatua en la población estadounidense que representa a las víctimas de este conflicto. En ella se encuentran tres niñas, una niña china, una coreana y una filipina, cogiéndose de las manos. El alcalde de Osaka, Hirofumi Yoshimura, y su predecesor, Toru Hashimoto, habían escrito cartas a su ciudad hermanada desde que se redactó la resolución para construir el memorial. Asimismo, dentro del propio LDP, Yoshitaka Sakurada, calificó de ‘prostitutas’ a este grupo de mujeres en 2016; poco después de haber establecido el tratado de 2015 sobre este tema. Eso ha provocado una respuesta negativa al tratado, ya que se cree que en realidad Japón no busca la reconciliación, sino olvidar el tema sin aceptar la responsabilidad que conlleva.

El problema radica en cómo afrontan la controversia estos países. La República de Corea, con el presidente Moon, busca cerrar las heridas pasadas con nuevos acuerdos, pero Japón solo aspira a cerrar el asunto lo antes posible. La renegociación de un tratado no es la mejor opción para Japón: incluso buscando la mejor solución para ambas partes, saldría perdiendo. En caso de que el presidente Moon logre llegar a un nuevo acuerdo con el primer ministro Abe para solventar los problemas del anterior tratado, se demostraría que las negociaciones anteriores y las medidas adoptadas por Japón en 2015 han fracasado.

Por muchas disculpas que el Gobierno de Japón haya emitido a lo largo de los años, nunca se ha aceptado la responsabilidad legal sobre las acciones en relación a las mujeres confort. Mientras que esto no suceda, no se pueden proyectar futuros escenarios donde la discusión se solucione. El presidente Moon renegociará el tratado con Japón, pero las probabilidades de que resulte son escasas. Todo indica que Japón no tiene ninguna intención de renegociar el tratado ni de hacerse cargo legalmente. Si no alcanzan una solución, las relaciones entre los dos países se pueden llegar a deteriorar debido a la carga emocional que presenta el problema.

La raíz de las tensiones se sitúa en el pasado histórico y su aceptación. Tanto Moon Jae-in como Shinzo Abe deben reevaluar la situación con ojos críticos en relación a sus propios países. Japón debe comenzar a comprometerse con las acciones pasadas y la República de Corea debe mantenerse una posición constante y decidir cuáles son sus prioridades respecto a las mujeres confort. Solo ello puede permitirles avanzar en la búsqueda del mejor tratado para ambos.

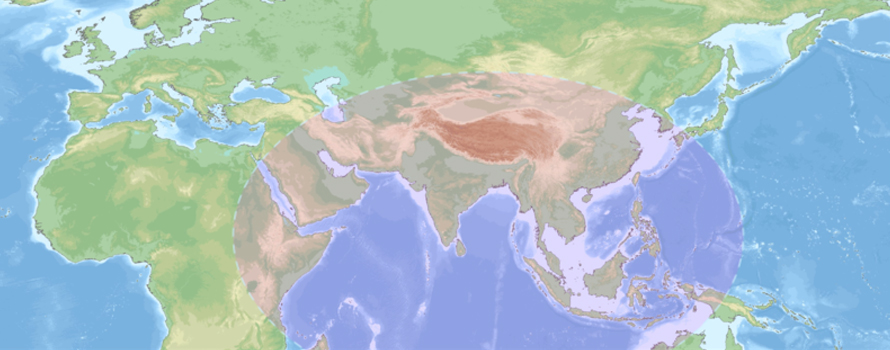

▲Área del Indo-Pacífico y territorios adyacentes [Wikimedia-Commons]

ANÁLISIS / Emili J. Blasco

Estamos asistiendo al nacimiento efectivo de Eurasia. Si esa palabra surgió como artificio, para reunir dos geografías adyacentes, sin relación, hoy Eurasia está emergiendo como realidad, en una única geografía. El catalizador ha sido sobre todo la apertura hacia Poniente de China: en la medida en que China ha comenzado a ocuparse de su parte trasera –Asia Central–, y ha dibujado nuevas rutas terrestres hacia Europa, las distancias entre los márgenes de Eurasia también se han ido reduciendo. Los mapas de la Iniciativa Cinturón y Ruta de la Seda tienen como efecto primero presentar un único continente, de Shanghái a París o Madrid. La guerra comercial entre Pekín y Washington y el desamparo europeo del otrora paraguas estadounidense contribuyen a que China y Europa se busquen mutuamente.

Una consecuencia de la mirada cruzada desde los dos extremos del supercontinente, cuyo encuentro construye ese nuevo mapa mental de territorio continuo, es que el eje mundial se traslada al Índico. Ya no está en el Atlántico, como cuando Estados Unidos retomó de Europa el estandarte de Occidente, ni tampoco en el Pacífico, adonde se había movido con el fenómeno emergente del Este asiático. Lo que parecía ser la localización del futuro, el Asia-Pacífico, está cediendo el paso al Indo-Pacífico, donde ciertamente China no pierde protagonismo, pero queda más sujeta al equilibrio de poder euroasiático. La ironía para China es que queriendo recuperar su pretérita posición de Reino del Medio, sus planes expansivos acaben dando centralidad a India, su velada némesis.

Eurasia se encoge

La idea de un encogimiento de Eurasia, que reduce su vasta geografía al tamaño de nuestro campo visual, ganando en entidad propia, fue expresada hace dos años por Robert Kaplan en un ensayo que luego ha recogido en su libro The Return of Marco Polo's World (2018)[1]. Justamente el renacimiento de la Ruta de la Seda, con sus reminiscencias históricas, es lo que ha acabado por poner en un mismo plano en nuestra mente Europa y Oriente, como en unos siglos en los que, desconocida América, no existía nada allende los océanos circundantes. “A medida que Europa desaparece”, dice Kaplan en referencia a las crecientemente vaporosas fronteras europeas, “Eurasia se cohesiona”. “El supercontinente se está convirtiendo en una unidad fluida y global de comercio y conflicto”, afirma.

Para Bruno Maçães, autor de The Down of Eurasia (2018)[2], hemos entrado en una era euroasiática. A pesar de lo que cabría haber predicho hace tan solo un par de décadas, “este siglo no será asiático”, asegura Maçães. Tampoco será europeo o americano, sino que estamos como en aquel momento, al término de la Primera Guerra Mundial, cuando se pasó de hablar de Europa a hacerlo de Occidente. Ahora Europa, desprendida de Estados Unidos, según argumenta este autor portugués, también pasa a integrarse en algo mayor: Eurasia.

Teniendo en cuenta ese movimiento, tanto Kaplan como Maçães vaticinan una disolución de Occidente. El americano pone el acento en las deficiencias de Europa: “Europa, al menos como la hemos conocido, ha comenzado a desaparecer. Y con ella Occidente mismo”; mientras que el europeo señala más bien el desinterés de Estados Unidos: “Uno tiene la sensación de que la vocación universalista estadounidense no es garantizar la preeminencia global de la civilización occidental, sino seguir como la única superpotencia global”.

Cambia el eje del mundo

A raíz del descubrimiento español de América, en el siglo XVI se veía coronar una traslación gradual hacia Occidente de la hegemonía y de la civilización en el mundo. “Los imperios de los persas y de los caldeos habían sido reemplazados por los de Egipto, Grecia, Italia y Francia, y ahora por el de España. Aquí permanecería el centro del mundo”, escribe John Elliott citando un escrito de la época, del humanista Pérez de Oliva[3]. La idea de estación final también se tuvo cuando el peso específico del mundo se situó en el Atlántico, y luego en el Pacífico. Hoy proseguimos de nuevo ese viraje hacia Poniente, hasta el Índico, sin ya quizá mucho ánimo de darlo por definitivo, aunque se complete la vuelta sobre cuyos inicios teorizaron los renacentistas.

Al fin y al cabo, también ha habido traslaciones del centro de gravedad en sentido contrario, si atendemos a otros parámetros. En las décadas posteriores a 1945 la localización media de la actividad económica entre diferentes geografías estuvo situada en el centro del Atlántico. Con el cambio de siglo, sin embargo, el centro de gravedad de las transacciones económicas ha estado emplazado al Este de las fronteras de la Unión Europea, según apunta Maçães, quien pronostica que en diez años el punto medio estará en la frontera entre Europa y Asia, y a mitad del siglo XXI entre India y China, países que están “abocados a desarrollar la mayor relación comercial del mundo”. Con ello, India “puede convertirse en el nudo central entre los extremos del nuevo supercontinente”. Moviéndonos hacia un lado del planeta hemos llegado al mismo punto –el Índico– que en el viaje en sentido contrario.

El mundo isla

A diferencia del Atlántico y del Pacífico, océanos que en el globo se extienden verticalmente, de polo a polo, el Índico se despliega horizontalmente y en lugar de encontrar dos riberas, tiene tres. Eso hace que África, al menos su zona oriental, forme parte también de esta nueva centralidad: si la rapidez de navegación propiciada por los monzones ya facilitó históricamente un estrecho contacto del subcontinente indio con la costa este africana, hoy las nuevas rutas de la seda marítimas pueden acrecentar aún más los intercambios. Eso y la creciente llegada de migrantes subsaharianos a Europa refleja un fenómeno centrípeto que incluso da pie a hablar de Afro-Eurasia. Así que, como apunta Kaplan, referirse al mundo isla como en su día hizo Halford Mackinder “ya no es algo prematuro”. Maçães recuerda que Mackinder veía como una dificultad para percibir la realidad de ese mundo isla el hecho de que no fuera posible circunnavegarlo por completo. Hoy esa percepción debiera ser más fácil, cuando se está abriendo la ruta del Ártico.

En el marco de las teorías complementarias –verso y reverso– de Halford Mackinder y de Nicholas Spykman sobre el Heartland y el Rimland, respectivamente, cualquier centralidad de India tiene que traslucirse en poder marítimo. Cerrado su acceso al interior de Asia por el Himalaya y por un antagónico Pakistán (le queda el único y complejo paso de Cachemira), es en el mar donde India puede proyectar su influencia. Como India, también China y Europa están en el Rimland euroasiático, desde donde todas esas potencias disputarán el equilibrio de poder entre ellas y también con el Heartland, que básicamente ocupa Rusia, auque no en exclusiva: en el Heartland también se encuentran las repúblicas centroasiáticas, que cobran un especial valor en la competencia por el espacio y los recursos de un encogido supercontinente.

Pivot a Eurasia

En esta región del Indo-Pacífico, o del Gran Índico, que va del Golfo Pérsico y las costas de África oriental hasta la segunda cadena de islas de Asia-Pacífico, a Estados Unidos le corresponde un papel exterior. En la medida en que el mundo isla se cohesiona, queda más remarcado el carácter satelital estadounidense. La gran estrategia de Estados Unidos deviene entonces en lo que ha sido el tradicional imperativo del Reino Unido con respecto a Europa: impedir que una potencia domine el continente, algo que más fácilmente se logra apoyando a una u otra potencia continental para debilitar a la que en cada momento sea más fuerte (Francia o Alemania, según la época histórica; hoy Rusia o China). Ya en la Guerra Fría, Estados Unidos se esforzó por impedir que la URSS se alzara en hegemón al controlar también Europa Occidental. Eurasia entra en un juego de equilibrio de poder presumiblemente intenso, como lo fue el escenario europeo entre el siglo XIX y el XX.

Por eso, Kaplan dice que Rusia puede ser contenida mucho más por China que por Estados Unidos, como también Washington debiera aprovechar a Rusia para limitar el poder de China, a sugerencia de Henry Kissinger. Para ello, el Pentágono debiera ampliar hacia el Oeste la presencia estratégica que tiene en el Pacífico Occidental: si como potencia exterior y marítima no puede acceder al centro continental de Eurasia, sí puede tomar posición en las entrañas mismas de esa gran región, que es el propio Índico.

“Si Obama hizo el pivot a Asia, entonces Trump ha pivotado a Eurasia. Quienes toman decisiones en Estados Unidos parecen crecientemente conscientes de que el nuevo centro de gravedad en la política mundial no es el Pacífico ni el Atlántico, sino el Viejo Mundo entre los dos”, ha escrito Maçães en un ensayo posterior a su libro[4].

|

Imagen de la presentación oficial de la Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy japonesa [Mº Exteriores de Japón] |

Alianzas con India

El cambio de foco desde Asia-Pacífico al Indo-Pacífico por parte de Estados Unidos fue expresado formalmente en la Estrategia de Seguridad Nacional publicada en diciembre de 2017, el primero de ese tipo de documentos elaborado por la Administración Trump. Consecuentemente, Estados Unidos ha rebautizado su Comando del Pacífico como Comando del Indo-Pacífico.

La estrategia de Washington, como la de otros destacados países occidentales de la región, sobre todo Japón y Australia, pasa por una coalición de algún tipo con India, por el carácter central de este país y como mejor manera de contener a China y Rusia.

La conveniencia de una mayor relación con Nueva Dehli ya fue esbozada por Trump durante la visita del primer ministro indio, Narendra Modi, a Washington en junio de 2017, y luego por el entonces secretario de Estado, Rex Tillerson, en octubre de 2017. El sucesor de este, Mike Pompeo, abordó un marco más definido en julio de 2018, cuando anunció ayudas de 113 millones de dólares para proyectos destinados a lograr una mayor conectividad de la región, desde tecnologías digitales a infraestructuras. El anuncio fue entendido como el deseo estadounidense de hacer frente a la Iniciativa Cinturón y Ruta de la Seda lanzada por China.

En ocasiones, la Estrategia para el Indo-Pacífico de Estados Unidos se presenta asociada a la Estrategia para un Indo-Pacífico Libre y Abierto (FOIP), que es el nombre puesto por Japón para su propia iniciativa de cooperación para la región, ya expuesta hace diez años por el primer ministro japonés Shinzo Abe. Ambas son coincidentes en contar con India, Japón, Australia y Estados Unidos como los principales garantes de la seguridad regional, pero presentan dos principales divergencias. Una es que para Washington el Indo-Pacífico va desde el litoral oriental de India hasta la costa oeste estadounidense, mientras que en la iniciativa japonesa el mapa va del Golfo Pérsico y la costa africana a Filipinas y Nueva Zelanda. La otra tiene que ver con la manera de percibir a China: la propuesta japonesa busca la cooperación china, al menos en el nivel declarativo, mientras que el propósito estadounidense es hacer frente a los “riesgos de dominio chino”, como se consigna en la Estrategia de Seguridad Nacional.

India también ha elaborado una iniciativa propia, presentada en 2014 como Act East Policy (AEP), con el objeto de potenciar una mayor cooperación entre India y los países de Asia-Pacífico, especialmente de la ASEAN. Por su parte, Australia expuso su Policy Roadmap para la región en 2017, que descansa en la seguridad que ya viene prestando Estados Unidos y aboga por un continuado entendimiento con las “las democracias indo-pacíficas” (Japón, Corea del Sur, India e Indonesia).

Otras consecuencias

Algunas otras consecuencias del nacimiento de Eurasia, de diferente orden e importancia, son:

–La Unión Europea no solo está dejando de ser atrayente como proyecto político e incluso económico para sus vecinos, debido a sus problemas de convergencia interna, sino que la realidad de Eurasia la reduce a ser una península en los márgenes del supercontinente. Por ejemplo, pierde cualquier interés la vieja cuestión de si Turquía forma o no parte de Europa: Turquía va a tener una mejor posición en el tablero.

–Adquieren toda su importancia los corredores que China quiere tener abiertos hacia el Índico (Myanmar y, sobre todo, Pakistán). Sin poder recobrar el estatus milenario de Reino del Medio, China valorará aún más disponer de la provincia de Xinjiang como modo de estar menos escorada en un lado del supercontinente y como plataforma para una mayor proyección hacia el interior del mismo.

–El pivot a Eurasia por parte de Estados Unidos obligará a Washington a distribuir sus fuerzas en una mayor extensión de mar y sus riberas, con el riesgo de perder poder disuasorio o de intervención en determinados lugares. Cuidar el Índico puede llevarle, sin pretenderlo, a descuidar el Mar de China Meridional. Un modo de ganar influencia en el Índico sin gran esfuerzo podría ser trasladar la sede de la Quinta Flota de Bahréin a Omán, igualmente a un paso del estrecho de Ormuz, pero fuera del Golfo Pérsico.

–Rusia se ha visto tradicionalmente como un puente entre Europa y Asia, y ha contado con alguna corriente defensora de un euroasianismo que presentaba Eurasia como un tercer continente (Rusia), con Europa y Asia a cada lado, y que reservaba el nombre de Gran Eurasia al supercontinente. En la medida en que este se encoja, Rusia se beneficiará de la mayor conectividad entre un extremo y otro y estará más encima de sus antiguas repúblicas centroasiáticas, aunque estas tendrán contacto con un mayor número de vecinos.

(1) Kaplan, R. (2018) The Return fo Marco Polo's World. War, Strategy, and American Interests in the Twenty-First Century. Nueva York: Random House

(2) Maçães, B. (2018) The Dawn of Eurasia. On the Trail of the New World Order. Milton Keynes: Allen Lane

(3) Elliott, J. (2015) El Viejo Mundo y el Nuevo (1492-165). Madrid: Alianza Editorial

(4) Maçães, B. (2018). Trump's Pivot to Eurasia. The American Interest. 21 de agosto de 2018

![Kim Jung-un and Moon Jae-in met for the first time in April, 2018 [South Korea Gov.] Kim Jung-un and Moon Jae-in met for the first time in April, 2018 [South Korea Gov.]](/documents/10174/16849987/soft-power-corea-blog.jpg)

▲Kim Jung-un and Moon Jae-in met for the first time in April, 2018 [South Korea Gov.]

ANALYSIS / Kanghun Ji

North Korea has always utilized its nuclear power as a leverage for negotiation in world politics. Nuclear weapons, asymmetric power, are the last measure for North Korea which lacks absolute military and economic power. Although North Korea lags behind the United States and South Korea in military/economic power, its possession of nuclear weapons renders it a significant threat to other countries. Recently, however, they have continued to develop their nuclear power in disregard of international regulations. In other words, they have not used nuclear issue as a leverage for negotiation to induce economic support. They have rather concentrated on completing nuclear development, not considering persuasion from peripheral countries. This attitude can be attributed to the fact that the development of their nuclear power is almost complete. Many experts say that North Korea judges the recognition of their nation with nuclear power to be a more powerful negotiation tool (Korea times, 2016).

In this situation, South Korea has been trying many different kinds of strategies to resolve the nuclear crisis because security is their main goal: United States-South Korea joint military exercises and United Nations sanctions against North Korea are some of those strategies. Despite these oppressive methods using hard power, North Korea has refused to participate in negotiations.

Most recently, however, North Korea has discarded its previous stance for a more peaceful and amicable position following the PyeongChang Olympics. Discussions about nuclear power are proceeding and the nation has even declared that they will stop developing nuclear power.

Diverse causes such as international relations or economic needs influence their transition. This essay would argue that the soft power strategies of South Korea are substantially influencing North Korea. Therefore, an analysis of South Korea’s soft power strategies is necessary in order to figure out the successful way to resolve the nuclear crisis.

Importance of soft-power strategies in policies against North Korea

North Korea has justified its dictatorship through the development of its ‘Juche’ ideology which is very unique. This ideology is established on the theory of ‘rule by class’ which stems from Marxism-Leninism. In addition, the regime has combined it with Confucianism that portrays a dictator as a father of family (Jung Seong Jang, 1999). Through this justification, a dictator is located at the top of class, which would complete the communist ideal. People are taught this ideology thoroughly and anyone who violates the ideology is punished. To open up this society which has formerly been ideologically closed, their ideology should be undermined by other attractive ideology, culture, and symbol.

However, North Korea has effectively blocked it. For example, recently, many people in North Korea have covertly shared TV shows and music from South Korea. People who are caught enjoying this culture are severely punished by the government. In these types of societies, oppression through hard power strategies doesn’t affect making any kind of change in internal society. It rather could be used to enhance internal solidarity because the potential offenders such as United States or South Korea are postulated as certain enemies to North Korea, which requires internal solidarity to people. North Korea has actually depicted capitalism, United States and South Korea as the main enemies in media. It intends to induce loyalty from people.

As a result, the regime have developed nuclear weapons successfully under strong censorship. Nuclear power is the main key to maintain the dictatorship. The declaration of ‘Nuclear-Economy parallel development’ from the start of Kim Jung-Eun’s government implies that the regime would ensure nuclear weapon as a measure to maintain its system. In this situation, sending the message that its system can coordinately survive alongside South Korea in world politics is important. Not only oppressive strategies but also appropriate strategies which attract North Korea to negotiate are needed.

Analysis of South Korea Soft Power Strategies

In this analysis, I will employ a different concept of soft power compared from the one given by Joseph Nye. Nye’s original concept of soft power focuses on types of behavior. In terms of his concept, co-optive power such as attraction and persuasion also constitutes soft power regardless of the type of resource (Joseph Nye, 2013). However, the concept of soft power I will use focuses on what types of resources users use regardless of the type of behaviors. Therefore, any kinds of power exerted by only soft resources such as images, diplomacy, agenda-setting and so on could be soft power. It is a resource-based concept compared to Nye’s concept which is behavior based (Geun Lee, 2011).

I use this concept because using hard resources such as military power and economic regulation to resolve the nuclear problem in North Korea has been ineffective so far. Therefore, using the concept of soft power which is based on soft resources makes it possible to analyze different kinds of soft power and find ways to improve it.

According to the thesis by Geun Lee (2011: p.9) who used the concept I mentioned above, there are 4 categories of Soft Power. I will use these categories to analyze the soft power strategies of South Korea.

|

1. Application of soft resources – Fear – Coercive power (or resistance) |

|

2. Application of soft resources – Attractiveness, Safety, Comfort, Respect – Co-optive power |

|

3. Application of soft resources (theories, interpretative frameworks) – New ways of thinking and calculating – Co-optive power |

|

4. Socialization of the co-optive power in the recipients – Long term soft power in the form of “social habit” |

1. Oppression through diplomacy: Two-track diplomacy

South Korea takes advantage of soft power strategies that request a global mutual-assistance system in order to oppress North Korea. Based on diplomatic capabilities, South Korea has tried to make it clear that all countries in world politics are demanding a solution to the North Korean nuclear crisis. Through these strategies, it wants to provoke fear in North Korea that it would be impossible to restore its relationship with the world. These strategies have been influential because they are harmonized with United Nations’ Security Council resolutions. Especially, the two-track diplomacy conducted by the president Moon-jae-in in the United Nations general assembly in 2017 is evaluated to be successful. He gave North Korea two options in order to attract them to negotiate (The fact, 2017). The president Moon-jae-in stressed the importance of cooperation about nuclear crisis among countries in his address to the general assembly. Moreover, he discussed the issue with the presidents of United States and Japan and pushed for a firm stance against the North Korea nuclear problem. However, at the same time, he declared that South Korea is ready for peaceful negotiation and discussion if North Korea wish to negotiate and stop developing its nuclear power. By offering two options, South Korea not only aimed to incite fear in North Korea but also left room for North Korea to appear at the negotiation tables.

Strategies using diplomatic capabilities are valuable because they can induce coercive power through soft resources. However, it would be difficult to judge the effectiveness if North Korea didn’t show any reaction to these strategies. Moreover, the cooperation with Russia and China is very important to persuade North Korea because they are maintaining amicable relationships with North Korea against United States and Japan. In the situation that North Korea has aimed to complete development of nuclear weapons for negotiation, diplomatic oppression is not effective itself for making change.

|

Joint statement by the leaders of North and South Korea, in April 2018 [South Korea Gov.] |

2. Sports and culture: Peaceful gesture

The attempt to converse through sports and culture is one of the soft power strategies used by South Korea in order to solve the nuclear crisis. This strategy intends to obtain North Korea’s cooperation in non-political areas which could then spread to political negotiations. As a result of this strategy, South Korea and North Korea formed a unified team during the last Olympics and Asian games (Yonhapnews, 2018). However, for it to be a success, their cooperation should not be limited to the non-political area, but instead should lead to a constructive conversation in politics. In these terms, South Korea’s peaceful gesture in the Pyeong-Chang winter Olympic is seen to have brought about positive change. Before the Olympics, many politicians and experts were skeptical to the gesture because North Korea conducted the 6th nuclear test in 2017, ignoring South Korea’s message (Korea times, 2018). In extension of the two-track diplomacy strategy, nevertheless, the South Korea government has continually shown a desire to cooperate with North Korea. These strategies focus on cooperation only in soft power domains such as sports, culture, and music rather than domains that expose serious political intension.

In the United Nations general assembly which adopted a truce for the Pyeong-Chang Olympics, gold medalist Kim-yun-a required North Korea to participate in Olympics on her address (Chungang, 2017). Moreover, in the event for praying successful Olympics, the president Moon-jae-in sent another peaceful gesture mentioning that South Korea would wait for the participation of North Korea until the beginning of Olympics (Voakorea, 2017). This strategy ended up having successfully attracted North Korea. As a result, they composed a unified ice hockey team and diplomats were dispatched from North Korea during the Olympics to watch the game with South Korean government officials. And then, they exchanged cultural performances in Pyeong-Chang and Pyeong-yang. Finally, the efforts led to the summit meeting between South-North Korea, and North Korea even declared that it would stop developing nuclear power and establish cooperation with South Korea.