Breadcrumb

Blogs

Entries with Categorías Global Affairs Análisis .

Temporary Protected Status for Venezuelans and pending TPS termination for Central Americans amid a migration surge at the US-Mexico border

The Venezuelan flag near the US Capitol [Rep. Darren Soto]

ANALYSIS / Alexandria Angela Casarano

On March 8, the Biden administration approved Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for the cohort of 94,000 to 300,000+ Venezuelans already residing in the United States. Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti await the completion of litigation against the TPS terminations of the Trump administration. Meanwhile, the US-Mexico border faces surges in migration and detention facilities for unaccompanied minors battle overcrowding.

TPS and DED. The case of El Salvador

TPS was established by the Immigration Act of 1990 and was first granted to El Salvador that same year due to a then-ongoing civil war. TPS is a temporary immigration benefit that allows migrants to access education and obtain work authorization (EADs). TPS is granted to specific countries in response to humanitarian, environmental, or other crises for 6, 12, or 18-month periods—with the possibility of repeated extension—at the discretion of the Secretary of Homeland Security, taking into account the recommendations of the State Department.

The TPS designation of 1990 for El Salvador expired on June 30,1992. However, following the designation of Deferred Enforced Departure (DED) to El Salvador on June 26, 1992 by George W. Bush, Salvadorans were allowed to remain in the US until December 31, 1994. DED differs from TPS in that it is designated by the US President without the obligation of consultation with the State Department. Additionally, DED is a temporary protection from deportation, not a temporary immigration benefit, which means it does not afford recipients a legal immigration status, although DED also allows for work authorization and access to education.

When DED expired for El Salvador on December 31, 1994, Salvadorans previously protected by the program were granted a 16-month grace period which allowed them to continue working and residing in the US while they applied for other forms of legal immigration status, such as asylum, if they had not already done so.

The federal court system became significantly involved in the status of Salvadoran immigrants in the US beginning in 1985 with the American Baptist Churches v. Thornburgh (ABC) case. The ABC class action lawsuit was filed against the US Government by more than 240,000 immigrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, and former Soviet Bloc countries, on the basis of alleged discriminatory treatment of their asylum claims. The ABC Settlement Agreement of January 31, 1991 created a 240,000-member immigrant group (ABC class members) with special legal status, including protection from deportation. Salvadorans protected under TPS and DED until December 31, 1994 were allowed to apply for ABC benefits up until February 16, 1996.

Venezuela and the 2020 Elections

The 1990’s Salvadoran immigration saga bears considerable resemblance to the current migratory tribulations of many Latin American immigrants residing in the US today, as the expiration of TPS for four Latin American countries in 2019 and 2020 has resulted in the filing of three major lawsuits currently working their way through the US federal court system.

Approximately 5 million Venezuelans have left their home country since 2015 following the consolidation of Nicolás Maduro, on economic grounds and in pursuit of political asylum. Heavy sanctions placed on Venezuela by the Trump administration have exacerbated—and continue to exacerbate, as the sanctions have to date been left in place by the Biden administration—the severe economic crisis in Venezuela.

An estimated 238,000 Venezuelans are currently residing in Florida, 67,000 of whom were naturalized US citizens and 55,000 of whom were eligible to vote as of 2018. 70% of Venezuelan voters in Florida chose Trump over Biden in the 2020 presidential elections, and in spite of the Democrats’ efforts (including the promise of TPS for Venezuelans) to regain the Latino vote of the crucial swing state, Trump won Florida’s 29 electoral votes in the 2020 elections. The weight of the Venezuelan vote in Florida has thus made the humanitarian importance of TPS for Venezuela a political issue as well. The defeat in Florida has probably made President Biden more cautious about relieving the pressure on Venezuela's and Cuba's regimes.

The Venezuelan TPS Act was originally proposed to the US Congress on January 15, 2019, but the act failed. However, just before leaving office, Trump personally granted DED to Venezuela on January 19, 2021. Now, with the TPS designation to Venezuela by the Biden administration on March 8, Venezuelans now enjoy a temporary legal immigration status.

The other TPS. Termination and ongoing litigation

Other Latin American countries have not fared so well. At the beginning of 2019, TPS was designated to a total of four Latin American countries: Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti. Nicaragua and Honduras were first designated TPS on January 5, 1999 in response to Hurricane Mitch. El Salvador was redesignated TPS on March 9, 2001 after two earthquakes hit the country. Haiti was first designated TPS on January 21, 2010 after the Haiti earthquake. Since these designations, TPS was continuously renewed for all four countries. However, under the Trump administration, TPS was allowed to expire without renewal for each country, beginning with Nicaragua on January 5, 2019. Haiti followed on July 22, 2019, then El Salvador on September 9, 2019, and lastly Honduras on January 4, 2020.

As of March 2021, Salvadorans account for the largest share of current TPS holders by far, at a total of 247,697, although the newly eligible Venezuelans could potentially overshadow even this high figure. Honduras and Haiti have 79,415 and 55,338 TPS holders respectively, and Nicaragua has much fewer with only 4,421.

The elimination of TPS for Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti would result in the deportation of many immigrants who for a significant continuous period of time have contributed to the workforce, formed families, and rebuilt their lives in the United States. Birthright citizenship further complicates this reality: an estimated 270,000 US citizen children live in a home with one or more parents with TPS, and the elimination of TPS for these parents could result in the separation of families. Additionally, the conditions of Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti—in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, recent natural disasters (i.e. hurricanes Matthew, Eta, and Iota), and other socioeconomic and political issues—remain far from ideal and certainly unstable.

Three major lawsuits were filed against the US Government in response to the TPS terminations of 2019 and 2020: Saget v. Trump (March 2018), Ramos v. Nielsen (March 2018), and Bhattarai et al. v. Nielsen (February 2019). Kirstjen Nielsen served as Secretary of Homeland Security for two years (2017 - 2019) under Trump. Saget v. Trump concerns Haitian TPS holders. Ramos v. Nielsen concerns 250,000 Salvadoran, Nicaraguan, Haitain and Sudanese TPS holders, and has since been consolidated with Bhattarai et al. v. Nielsen which concerns Nepali and Honduran TPS holders.

All three (now two) lawsuits appeal the TPS eliminations for the countries involved on similar grounds, principally the racial animus (i.e. Trump’s statement: “[Haitians] all have AIDS”) and unlawful actions (i.e. violations of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA)) of the Trump administration. For Saget v. Trump, the US District Court (E.D. New York) blocked the termination of TPS (affecting Haiti only) on April 11, 2019 through the issuing of preliminary injunctions. For Ramos v. Nielson (consolidated with Bhattarai et al. v. Nielson), the US Court of Appeals of the 9th Circuit has rejected these claims and ruled in favor of the termination of TPS (affecting El Salvador, Nicaragua, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, and Sudan) on September 14, 2020. This ruling has since been appealed and is currently awaiting revision.

The US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) have honored the orders of the US Courts not to terminate TPS until the litigation for these aforementioned cases is completed. The DHS issued a Federal Register Notice (FRN) on December 9, 2020 which extends TPS for holders from Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti until October 14, 2021. The USCIS has similarly cooperated and has ordered that so long as the litigation remains effective, no one will lose TPS. The USCIS has also ordered that in case of TPS elimination once the litigation is completed, Nicaragua and Haiti will have 120 grace days to orderly transition out of TPS, Honduras will have 180, and El Salvador will have 365 (time frames which are proportional to the number of TPS holders from each country, though less so for Haiti).

The Biden Administration’s Migratory Policy

On the campaign trail, Biden repeatedly emphasized his intentions to reverse the controversial immigration policies of the Trump administration, promising immediate cessation of the construction of the border wall, immediate designation of TPS to Venezuela, and the immediate sending of a bill to create a “clear [legal] roadmap to citizenship” for 11 million+ individuals currently residing in the US without legal immigration status. Biden assumed office on January 20, 2021, and issued an executive order that same day to end the government funding for the construction of the border wall. On February 18, 2021, Biden introduced the US Citizenship Act of 2021 to Congress to provide a legal path to citizenship for immigrants residing in the US illegally, and issued new executive guidelines to limit arrests and deportations by ICE strictly to non-citizen immigrants who have recently crossed the border illegally. Non-citizen immigrants already residing in the US for some time are now only to be arrested/deported by ICE if they pose a threat to public safety (defined by conviction of an aggravated felony (i.e. murder or rape) or of active criminal street gang participation).

Following the TPS designation to Venezuela on March 8, 2021, there has been additional talk of a TPS designation for Guatemala on the grounds of the recent hurricanes which have hit the country.

On March 18, 2021, the Dream and Promise Act passed in the House. With the new 2021 Democrat majority in the Senate, it seems likely that this legislation which has been in the making since 2001 will become a reality before the end of the year. The Dream and Promise Act will make permanent legal immigration status accessible (with certain requirements and restrictions) to individuals who arrived in the US before reaching the age of majority, which is expected to apply to millions of current holders of DACA and TPS.

If the US Citizenship Act of 2021 is passed by Congress as well, together these two acts would make the Biden administration’s lofty promises to create a path to citizenship for immigrants residing illegally in the US a reality. Since March 18, 2021, the National TPS Alliance has been hosting an ongoing hunger strike in Washington, DC in order to press for the speedy passage of the acts.

The current migratory surge at the US-Mexico border

While the long-term immigration forecast appears increasingly more positive as Biden’s presidency progresses, the immediate immigration situation at the US-Mexico border is quite dire. Between December 2020 and February 2021, the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reported a 337% increase in the arrival of families, and an 89% increase in the arrival of unaccompanied minors. CBP apprehensions of migrants crossing the border illegally in March 2021 have reached 171,00, which is the highest monthly total since 2006.

Currently, there are an estimated 4,000 unaccompanied minors in CBP custody, and an additional 15,000 unaccompanied minors in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

The migratory CBP facility in Donna, TX designated specifically to unaccompanied minors has been filled at 440% to 900% of its COVID-19 capacity of just 500 minors since March 9, 2021. Intended to house children for no more than a 72-hour legal limit, due to the current overwhelmed system, some children have remained in the facility for more than weeks at a time before being transferred on to HHS.

In order to address the overcrowding, the Biden administration announced the opening of the Delphia Emergency Intake Site (next to the Donna facility) on April 6, 2021, which will be used to house up to 1,500 unaccompanied minors. Other new sites have been opened by HHS in Texas and California, and HHS has requested the Pentagon to allow it to temporarily utilize three military facilities in these same two states.

Political polarization has contributed to a great disparity in the interpretation of the recent surge in migration to the US border since Biden took office. Termed a “challenge” by Democrats and a “crisis” by Republicans, both parties offer very different explanations for the cause of the situation, each placing the blame on the other.

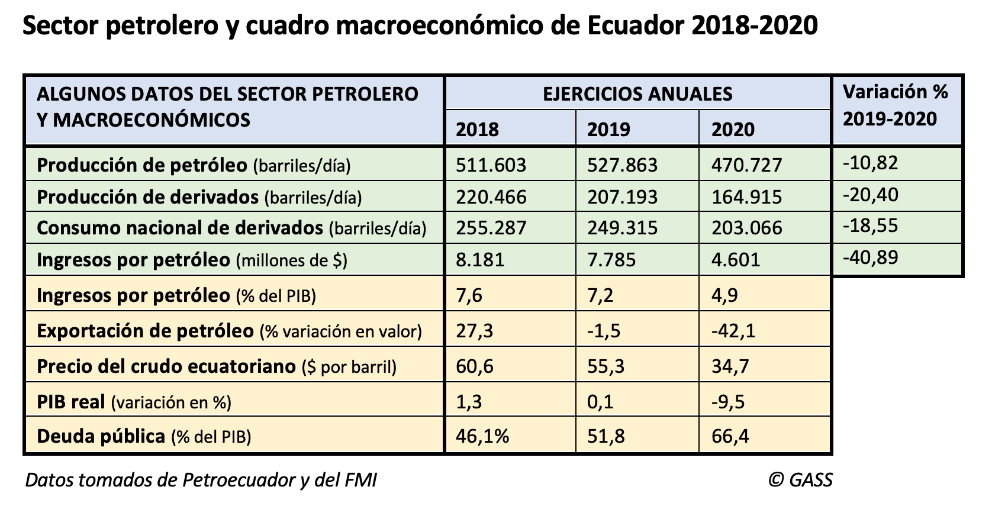

El país dejó el cartel para poder ampliar su bombeo, pero la crisis del Covid-19 ha recortado los volúmenes de extracción en un 10,8%

Construcción de una variante del oleoducto que cruza los Andes, desde la Amazonía ecuatoriana hasta el Pacífico [Petroecuador]

ANÁLISIS / Jack Acrich y Alejandro Haro

Ecuador abandonó el 1 de enero de 2020 la Organización de Países Exportadores de Petróleo (OPEP) para evitar tener que seguir sumándose a los recortes de producción impuestos por el grupo y que este acuerda con el ánimo de provocar una subida del precio mundial del crudo. Ecuador prefería vender más barriles, aunque fuera a menor precio, porque exportando más en última instancia podría aumentar sus ingresos y así salir de su grave situación financiera, que la emergencia por coronavirus no ha hecho sino acentuar, con una caída del PIB en 2020 de momento estimada en el 9,5%.

Sin embargo, las dificultades económicas internas y la difícil coyuntura internacional no solo han impedido a Ecuador un expandir el bombeo, sino que la producción de crudo ha caído un 10,8% en este último año. Ecuador extrajo en 2020 una media de 472.000 barriles diarios de petróleo, lastrada especialmente por la fuerte reducción de actividad en abril con el comienzo del confinamiento y luego no compensada el resto del año. Se trata de un volumen que queda por debajo de la línea de los 500.000 que siempre se había superado los recientes ejercicios (en 2019 la producción fue de 528.000), de acuerdo con las cifras de Petroecuador, la compañía estatal de hidrocarburos. La reducción del consumo mundial durante el año del Covid-19 también tuvo su correlación en un descenso del consumo de derivados en Ecuador, sobre todo gasolina y diésel, que bajó un 18,5%.

Una inversión internacional constreñida por el contexto de pandemia y un consumo reducido marcaban una situación que difícilmente podía llevar a un incremento de la producción. En 2020, Ecuador tuvo una caída en el valor de las exportaciones petroleras del 42,1% (el doble que el total de exportaciones), lo que combinado con un deterioro del precio del barril supuso una reducción del 40,9% en los ingresos públicos procedentes del sector petrolero, según los datos del Fondo Monetario Internacional (FMI).

Las cifras de los dos primeros meses de 2021 indican una acentuación de la caída de la producción de crudo (-4,73% respecto a enero y febrero de 2020) y de derivados (-7,47%), así como de la exportación de estos (-22,8%).

Recorte del gasto y búsqueda de ingresos petroleros

La salida de la OPEP no constituía ningún riesgo especial para Ecuador, que ya se ausentó de la organización en un periodo anterior. Su escaso peso en la OPEP y la progresiva menor fuerza del propio cartel dejaban sin especial coste el intento ecuatoriano de ir por libre. La absoluta prioridad del gobierno de Lenín Moreno era reequilibrar el cuadro macroeconómico del país –maltrecho por elevado gasto público de su antecesor, Rafael Correa– y para eso necesitaba imperiosamente el incremento de los ingresos del Estado, una parte importante de los cuales proviene normalmente en Ecuador del sector de los hidrocarburos.

Cuando llegó a la presidencia en 2017, Moreno se dispuso a orientar el país hacia políticas energéticas más favorables al mercado. El presidente estaba decidido a romper con el enfoque nacionalista de su predecesor, cuyas políticas desincentivaron la inversión extranjera en la industria petrolera al mismo tiempo que aumentó la deuda pública significativamente. Entre los programas más costosos acometidos por Correa estuvo el de mantener altos subsidios para el consumo energético energía, con precios especialmente bajos para los combustibles.

Con el fin de superar la situación financiera en que se encontraba Ecuador cuando tomó la presidencia, Moreno se acercó al FMI para solicitar ayuda financiera, y se comprometió a reformas estructurales, entre las que estaba el desmonte gradual de los subsidios. Estas reformas, sin embargo, no fueron bien recibidas y el malestar social que se extendió por todo el país puso aún más presión sobre la industria petrolera.

En febrero de 2019, Moreno negoció un préstamo del FMI para ayudar a reducir el gran déficit fiscal y la enorme deuda externa del país, que para finales de 2018 había alcanzado el 46,1% del PIB y que doce meses después llegaría al 51,8%. El «rescate» comprometido era de 10.200 millones de dólares, de los cuales 6.500 procedían del FMI y el resto de otros organismos internacionales.

Como parte de las medidas de austeridad acordadas con el FMI, Moreno se vio forzado a poner fin a los subsidios gubernamentales que habían mantenido bajos los precios de la gasolina durante décadas. A comienzos de octubre de 2019 anunció un plan de recortes para ahorrar 2.270 millones de dólares al año, básicamente retirando el subsidio a los carburantes. El anuncio del decreto, que luego sería anulado, provocó de inmediato protestas masivas, tanto de transportistas como de sectores de bajos ingresos, así como también muy singularmente de las comunidades indígenas. La violencia callejera obligó al presidente a dejar unos días Quito e instalarse en Guayaquil.

Para resolver la necesidad de ingresos, Moreno buscó apoyarse en la industria petrolera, que representa aproximadamente un tercio de las exportaciones totales del país. Inicialmente expresó la intención de procurar subir desde los 545.000 barriles diarios de crudo que entonces se producían hasta casi 700.000.

Una de las medidas tomadas en esa dirección fue potenciar el desarrollo y la explotación del campo Ishpingo-Tiputini-Tambococha, con el objetivo de aumentar la producción de petróleo en 90.000 barriles diarios. Esta decisión encontró rechazo social por el daño ambiental que podía producir, ya que el Parque Nacional Yasuní, en la Amazonía ecuatoriana, que ha sido declarado zona protegida. El gobierno decidió entonces aplazar la ampliación de la producción, primero a 2021 y luego a 2022. La oposición fue especialmente liderada por las comunidades indígenas, en una movilización que en parte explica el éxito en las elecciones presidenciales de 2021 del movimiento indigenista Pachakutik, de Yaku Pérez, quien a punto estuvo de pasar a la segunda vuelta.

Otra de las medidas fue revertir algunas de las políticas emblemáticas de su predecesor. Por ejemplo, eliminó los contratos de servicios introducidos bajo el presidente Correa, restaurando así el modelo de contrato de producción compartida. Esta reforma fue más favorable para las compañías petroleras internacionales, ya que les permitíaa retener una parte de las reservas de crudo; también les ofreció incentivos financieros para invertir en el país. El nuevo modelo se aplicó por primera vez en las licitaciones adjudicabas durante la duodécima ronda petrolera de Intracampos, en la región de Oriente, que es rica en reservas de petróleo. Bajo esta modalidad de contrato, la administración de Moreno adjudicó siete de los ocho bloques de exploración en oferta con una inversión total de más de 1.170 millones de dólares.

Caída de la producción

Debido a la urgencia de aumentar los ingresos, Ecuador se resistió al plan de recortes de producción que la OPEP ha estado imponiendo a sus miembros en varios momentos desde la abrupta caída de precios del petróleo en 2014. Inicialmente la organización aceptó que algunos de sus miembros, con volúmenes de producción moderados o muy bajos respecto a cifras previas, como era el caso de Venezuela, mantuvieran sus ritmos de extracción. Pero no pudiendo ser ya más una excepción, Ecuador prefirió anunciar a finales de 2019 su marcha de la OPEP y no tener que reducir su producción hasta los 508.000 barriles diarios en 2020, que era la cuota que se le fijaba.

Lo llamativo es que el año pasado la producción finalmente bajó de los 528.000 barriles diarios de 2019 hasta los 472.000 (una caída del 10,8%), y no ya por decisiones tomadas en la sede de la OPEP en Viena sino por las dificultades de diverso tipo que ha supuesto la crisis del Covid-19. La exportación de petróleo por parte de Petroecuador bajó de 331.321 barriles diarios de 2019 a los 316.000, un retroceso del 4,6% que en términos monetario fue mayor, ya que el precio del barril de petróleo mixto ecuatoriano pasó de 55,3 dólares en 2019 a 34,7 en 2020.

Un elemento que dificulta que Ecuador pueda aprovechar mejor su potencial en hidrocarburos es que cuenta con una infraestructura insuficiente para el refinado del crudo. El país cuenta con tres refinerías, cuya capacidad no alcanza el volumen de consumo interno de derivados del petróleo, con lo que debe importar diésel, nafta y otros productos. Esto supone que en momentos de alto precio del crudo Ecuador se ve beneficiado en las exportaciones, pero también debe pagar una factura mayor en las importaciones de derivados. En 2020, Petroecuador tuvo que importar 137.300 barriles diarios.

La complicada coyuntura que ha supuesto la pandemia ha continuado presionando sobre la deuda pública de Ecuador, que a final de 2020 llegó al 66,4%, a pesar de todos los intentos de reducción llevados a cabo por el gobierno de Moreno.

El próximo presidente, que deberá tomar posesión a finales de mayo de 2021, tampoco tendrá mucho margen de maniobra debido a esos volúmenes de deuda y tendrá que seguir confiando en mayores ingresos petroleros para equilibrar las finanzas públicas. Las políticas expansivas del gasto durante la presidencia de Correa tuvieron lugar en el contexto del superciclo de las materias primas, que tanto benefició a Sudamérica, pero eso no parece que vaya a repetirse a corto plazo.

Pérdida de peso de la OPEP

Con su marcha de la OPEP, Ecuador abandonaba una organización internacional que se creó en 1960 con el objetivo de regular el mercado mundial de petróleo y controlar en cierta manera los precios del crudo. Los países fundadores fueron Irán, Irak, Kuwait, Arabia Saudí y Venezuela. Con el tiempo otros países pasaron a formar parte de la OPEP y hoy está conformada por trece miembros: Argelia, Angola, República del Congo, Guinea Ecuatorial, Gabón, Libia, Nigeria, Emiratos Árabes Unidos y los cinco países fundadores. Al crearse, la organización buscaba establecer, actuando como cartel, una especie de contrapeso frente a una serie de transnacionales energéticas occidentales, principalmente de Estados Unidos y Reino Unido. Los miembros de la OPEP conforman alrededor del 40% de la producción petrolera mundial y contienen cerca del 80% de las reservas probadas de petróleo en el planeta. Para ser admitido como miembro de la organización es necesario tener una exportación de petróleo considerable y compartir los que tienen los países miembros.

Ecuador entró en la OPEP en 1973, pero en 1992 suspendió su membresía. Posteriormente, en 2007 volvió a tener una participación activa hasta su baja en enero de 2020. Tomando en cuenta que Ecuador era uno de los miembros más pequeños de la OPEP realmente no tenía una gran influencia en la organización y su salida no supone ninguna sustancial merma para esta. No obstante, constituye una segunda marcha en solo un año, pues Catar, que tenía un mayor peso específico en el cartel, lo abandonó el 1 de enero de 2019. En su caso, su divorcio con la OPEP se debió a otras razones, como sus tensiones con Arabia Saudí y su deseo de enfocarse en el sector del gas, del que es uno de los mayores productores del mundo.

Esos movimientos son ejemplo del momento de pérdida de influencia que atraviesa la OPEP. Esto ha llevado a que establezca alianzas con productores que no forman parte de la organización como Rusia y algunos otros países formando la OPEP+. Con el declive de la producción petrolera en Venezuela y el decrecimiento en la capacidad de otros miembros para controlar sus producciones y exportaciones Arabia Saudí se ha ido consolidando cada vez más en el líder del cartel, representando cerca de un tercio de la producción total del mismo, con unos 9,4 millones de barriles diarios aproximadamente. De alguna manera quedan Arabia Saudí y Rusia, en un mano a mano, como los principales países que buscan un recorte de la producción para intentar aumentar los precios. Adicionalmente, gracias al frácking, Estados Unidos se ha convertido en el mayor productor petrolero representando una gran influencia en el mercado internacional de crudo afectando el poder que puede tener la OPEP.

Detainee in a Xinjiang re-education camp located in Lop County listening to “de-radicalization” talks [Baidu baijiahao]

Detainee in a Xinjiang re-education camp located in Lop County listening to “de-radicalization” talks [Baidu baijiahao]

ESSAY / Rut Noboa

Over the last few years, reports of human rights violations against Uyghur Muslims, such as extrajudicial detentions, torture, and forced labor, have been increasingly reported in the Xinjiang province's so-called “re-education” camps. However, the implications of the Chinese undertakings on the province’s ethnic minority are not only humanitarian, having direct links to China’s ongoing economic projects, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and natural resource extraction in the region. Asides from China’s economic agenda, ongoing projects in Xinjiang appear to prototype future Chinese initiatives in terms of expanding the surveillance state, particularly within the scope of technology. When it comes to other international actors, the Xinjiang dispute has evidenced a growing diplomatic split between countries against it, mostly western liberal democracies, and countries willing to at least defend it, mostly countries with important ties to China and dubious human rights records. The issue also has important repercussions for multinational companies, with supply chains of well-known international companies such as Nike and Apple benefitting from forced Uyghur labor. The situation in Xinjiang is critically worrisome when it comes to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly considering recent outbreaks in Kashgar, how highly congested these “reeducation” camps, and potential censorship from the government. Finally, Uyghur communities continue to be an important factor within this conversation, not only as victims of China’s policies but also as dissidents shaping international opinion around the matter.

The Belt and Road Initiative

Firstly, understanding Xinjiang’s role in China’s ongoing projects requires a strong geographical perspective. The northwestern province borders Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India, giving it important contact with other regional players.

This also places it at the very heart of the BRI. With it setting up the twenty-first century “Silk Road” and connecting all of Eurasia, both politically and economically, with China, it is no surprise that it has managed to establish itself as China’s biggest infrastructural project and quite possibly the most important undertaking in Chinese policy today. Through more and more ambitious efforts, China has established novel and expansive connections throughout its newfound spheres of influence. From negotiations with Pakistan and the establishment of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) securing one of the most important routes in the initiative to Sri Lanka defaulting on its loan and giving China control over the Hambantota Port, the Chinese government has managed to establish consistent access to major trade routes.

However, one important issue remains: controlling its access to Central Asia. One of the BRI’s initiative’s key logistical hubs is Xinjiang, where the Uyghurs pose an important challenge to the Chinese government. The Uyghur community’s attachment to its traditional lands and culture is an important risk to the effective implementation of the BRI in Xinjiang. This perception is exacerbated by existing insurrectionist groups such as the East Turkestan independence movement and previous events in Chinese history, including the existence of an independent Uyghur state in the early 20th century[1]. Chinese infrastructure projects that cross through the Xinjiang province, such as the Central Asian High-speed Rail are a priority that cannot be threatened by instability in the region, inspiring the recent “reeducation” and “de-extremification” policies.

Natural resource exploitation

Another factor for China’s growing control over the region is the fact that Xinjiang is its most important energy-producing region, even reaching the point where key pipeline projects connect the northwestern province with China's key coastal cities and approximately 60% of the province’s gross regional production comes from oil and natural gas extraction and related industries[2]. With China’s energy consumption being on a constant rise[3] as a result of its growing economy, control over Xinjiang is key to Chinese.

Additionally, even though oil and natural gas are the region’s main industries, the Chinese government has also heavily promoted the industrial-scale production of cotton, serving as an important connection with multinational textile-based corporations seeking cheap labor for their products.

This issue not only serves as an important reason for China to control the Uyghurs but also promotes instability in the region. The increased immigration from a largely Han Chinese workforce, perceived unequal distribution of revenue to Han-dominated firms, and increased environmental costs of resource exploitation have exacerbated the preexisting ethnic conflict.

A growing diplomatic split

The situation in Xinjiang also has important implications for international perceptions of Chinese propaganda. China’s actions have received noticeable backlash from several states, with 22 states issuing a joint statement to the Human Rights Council on the treatment of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang on July 8, 2019. These states called upon China “to uphold its national laws and international obligations and to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms”.

Meanwhile, on July 12, 2019, 50 (originally 37) other states issued a competing letter to the same institution, commending “China’s remarkable achievements in the field of human rights”, stating that people in Xinjiang “enjoy a stronger sense of happiness, fulfillment and security”.

This diplomatic split represents an important and growing division in world politics. When we look at the signatories of the initial letter, it is clear to see that all are developed democracies and most (except for Japan) are Western. Meanwhile, those countries that chose to align themselves with China represent a much more heterogeneous group with states from the Middle East, Asia, and Africa[4]. Many of these have questionable human rights records and/or receive important funding and investment from the Chinese government, reflecting both the creation of an alternative bloc distanced from Western political influence as well as an erosion of preexisting human rights standards.

China’s Muslim-majority allies: A Pakistani case study

The diplomatic consequences of the Xinjiang controversy are not only limited to this growing split, also affecting the political rhetoric of individual countries. In the last years, Pakistan has grown to become one of China’s most important allies, particularly within the context of CPEC being quite possibly one of the most important components of the BRI.

As a Muslim-majority country, Pakistan has traditionally placed pan-Islamic causes, such as the situations in Palestine and Kashmir, at the center of its foreign policy. However, Pakistan’s position on Xinjiang appears not just subdued but even complicit, never openly criticizing the situation and even being part of the mentioned letter in support of the Chinese government (alongside other Muslim-majority states such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE). With Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan addressing the General Assembly in September 2019 on islamophobia in post-9/11 Western countries as well as in Kashmir but conveniently omitting Uyghurs in Xinjiang[5], Pakistani international rhetoric weakens itself constantly. Due to relying on China for political and economic support, it appears that Pakistan will have to censor itself on these issues, something that also rings true for many other Muslim-majority countries.

Central Asia: complacent and supportive

Another interesting case study within this diplomatic split is the position of different countries in the Central Asian region. These states – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan – have the closest cultural ties to the Uyghur population. However, their foreign policy hasn’t been particularly supportive of this ethnic group with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan avoiding the spotlight and not participating in the UNHRC dispute and Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan being signatories of the second letter, explicitly supporting China. These two postures can be analyzed through the examples of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Kazakhstan has taken a mostly ambiguous position to the situation. Having the largest Uyghur population outside China and considering Kazakhs also face important persecution from Chinese policies that discriminate against minority ethnic groups in favor of Han Chinese citizens, Kazakhstan is quite possibly one of the states most affected by the situation in Xinjiang. However, in the last decades, Kazakhstan has become increasingly economically and, thus, politically dependent on China. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan implemented what some would refer to as a “multi-vector” approach, seeking to balance its economic engagements with different actors such as Russia, the United States, European countries, and China. However, with American and European interests in Kazakhstan decreasing over time and China developing more and more ambitious foreign policy within the framework of strategies such as the Belt and Road Initiative, the Central Asian state has become intimately tied to China, leading to its deafening silence on Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

A different argument could be made for Uzbekistan. Even though there is no official statistical data on the Uyghur population living in Uzbekistan and former president Islam Karimov openly stated that no Uyghurs were living there, this is highly questionable due to the existing government censorship in the country. Also, the role of Uyghurs in Uzbekistan is difficult to determine due to a strong process of cultural and political assimilation, particularly in the post-Soviet Uzbekistan. By signing the letter to the UNHCR in favor of China's practices, the country has chosen a more robust support of its policies.

All in all, the countries in Central Asia appear to have chosen to tolerate and even support Chinese policies, sacrificing cultural values for political and economic stability.

Forced labor, the role of companies, and growing backlash

In what appears to be a second stage in China’s “de-extremification” policies, government officials have claimed that the “trainees “in its facilities have “graduated”, being transferred to factories outside of the province. China claims these labor transfers (which it refers to as vocational training) to be part of its “Xinjiang Aid” central policy[6]. Nevertheless, human rights groups and researchers have become growingly concerned over their labor standards, particularly considering statements from Uyghur workers who have left China describing the close surveillance from personnel and constant fear of being sent back to detention camps.

Within this context, numerous companies (both Chinese and foreign) with supply chain connections with factories linked to forced Uyghur labor have become entangled in growing international controversies, ranging from sportswear producers like Nike, Adidas, Puma, and Fila to fashion brands like H&M, Zara, and Tommy Hilfiger to even tech players such as Apple, Sony, Samsung, and Xiaomi[7]. Choosing whether to terminate relationships with these factories is a complex choice for these companies, having to either lose important components of their intricate supply chains or face growing backlash on an increasingly controversial issue.

The allegations have been taken seriously by these groups with organizations such as the Human Rights Watch calling upon concerned governments to take action within the international stage, specifically through the United Nations Human Rights Council and by imposing targeted sanctions at responsible senior officials. Another important voice is the Coalition to End Forced Labour in the Uyghur Region, a coalition of civil society organizations and trade unions such as the Human Rights Watch, the Investor Alliance for Human Rights, the World Uyghur Congress, and the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, pressuring the brands and retailers involved to exclude Xinjiang from all components of the supply chain, especially when it comes to textiles, yarn or cotton as well as calling upon governments to adopt legislation that requires human rights due diligence in supply chains. Additionally, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, the same organization that carried out the initial report on forced Uyghur labor and surveillance beyond Xinjiang and within the context of these labor transfers, recently created the Xinjiang Data Project. This initiative documents ongoing Chinese policies on the Uyghur community with open-source data such as satellite imaging and official statistics and could be decidedly useful for human rights defenders and researchers focused on the topic.

One important issue when it comes to the labor conditions faced by Uyghurs in China comes from the failures of the auditing and certification industry. To respond to the concerns faced by having Xinjiang-based suppliers, many companies have turned to auditors. However, with at least five international auditors publicly stating that they would not carry out labor-audit or inspection services in the province due to the difficulty of working with the high levels of government censorship and monitoring, multinational companies have found it difficult to address these issues[8]. Additionally, we must consider that auditing firms could be inspecting factories that in other contexts are their clients, adding to the industry’s criticism. These complaints have led human rights groups to argue that overarching reform will be crucial for the social auditing industry to effectively address issues such as excessive working hours, unsafe labor conditions, physical abuse, and more[9].

Xinjiang: a prototype for the surveillance state

From QR codes to the collection of biometric data, Xinjiang has rapidly become the lab rat for China’s surveillance state, especially when it comes to technology’s role in the issue.

One interesting area being massively affected by this is travel. As of September 2016, passport applicants in Xinjiang are required to submit a DNA sample, a voice recording, a 3D image of themselves, and their fingerprints, much harsher requirements than citizens in other regions. Later in 2016, Public Security Bureaus across Xinjiang issued a massive recall of passports for an “annual review” followed by police “safekeeping”[10].

Another example of how a technologically aided surveillance state is developing in Xinjiang is the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP), a big data program for policing that selects individuals for possible detention based on specific criteria. According to the Human Rights Watch, which analyzed two leaked lists of detainees and first reported on the policing program in early 2018, the majority of people identified by the program are being persecuted because of lawful activities, such as reciting the Quran and travelling to “sensitive” countries such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Additionally, some criteria for detention appear to be intentionally vague, including “being generally untrustworthy” and “having complex social ties”[11].

Xinjiang’s case is particularly relevant when it comes to other Chinese initiatives, such as the Social Credit System, with initial measures in Xinjiang potentially aiding to finetune the details of an evolving surveillance state in the rest of China.

Uyghur internment camps and COVID-19

The implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Uyghurs in Xinjiang are pressing issues, particularly due to the virus’s rapid spread in highly congested areas such as these “reeducation” camps.

Currently, Kashgar, one of Xinjiang’s prefectures is facing China’s most recent coronavirus outbreak[12]. Information from the Chinese government points towards a limited outbreak that is being efficiently controlled by state authorities. However, the authenticity of this data is highly controversial within the context of China’s early handling of the pandemic and reliance on government censorship.

Additionally, the pandemic has more consequences for Uyghurs than the virus itself. As the pandemic gives governments further leeway to limit rights such as the right to assembly, right to protest, and freedom of movement, the Chinese government gains increased lines of action in Xinjiang.

Uyghur communities abroad

The situation for Uyghurs living abroad is far from simple. Police harassment of Uyghur immigrants is quite common, particularly through the manipulation and coercion of their family members still living in China. These threatening messages requesting personal information or pressuring dissidents abroad to remain silent. The officials rarely identify themselves and in some cases these calls or messages don’t necessarily even come from government authorities, instead coming from coerced family members and friends[13]. One interesting case was reported in August 2018 by US news publication The Daily Beast in which an unidentified Uyghur American woman was asked by her mother to send over pictures of her US license plate number, her phone number, her bank account number, and her ID card under the excuse that China was creating a new ID system for all Chinese citizens, even those living abroad[14]. A similar situation was reported by Foreign Policy when it came to Uyghurs in France who have been asked to send over home, school, and work addresses, French or Chinese IDs, and marriage certificates if they were married in France[15].

Regardless of Chinese efforts to censor Uyghur dissidents abroad, their nonconformity has only grown with the strengthening of Uyghur repression in mainland China. Important international human rights groups such as Amnesty International and the Human Rights Watch have been constantly addressing the crisis while autonomous Uyghur human rights groups, such as the Uyghur Human Rights Project, the Uyghur American Association, and the Uyghur World Congress, have developed from communities overseas. Asides from heavily protesting policies such as the internment camps and increasing surveillance in Xinjiang, these groups have had an important role when it comes to documenting the experiences of Uyghur immigrants. However, reports from both human rights group and media agencies when it comes to the crisis have been met with staunch rejection from China. One such case is the BBC being banned in China after recently reporting on Xinjiang internment camps, leading it to be accused of not being “factual and fair” by the China National Radio and Television Administration. The UK’s Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab referred to the actions taken by the state authorities as “an unacceptable curtailing of media freedom” and stated that they would only continue to damage China’s international reputation[16].

One should also think prospectively when it comes to Uyghur communities abroad. As seen in the diplomatic split between countries against China’s policies in Xinjiang and those who support them (or, at the very least, are willing to tolerate them for their political interest), a growing number of countries can excuse China’s treatment of Uyghur communities. This could eventually lead to countries permitting or perhaps even facilitating China’s attempts at coercing Uyghur immigrants, an important prospect when it comes to countries within the BRI and especially those with an important Uyghur population, such as the previously mentioned example of Kazakhstan.

REFERENCES

[1] Qian, Jingyuan. 2019. “Ethnic Conflicts and the Rise of Anti-Muslim Sentiment in Modern China.” Department of Political Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3450176.

[2] Cao, Xun, Haiyan Duan, Chuyu Liu, James A. Piazza, and Yingjie Wei. 2018. “Digging the “Ethnic Violence in China” Database: The Effects of Inter-Ethnic Inequality and Natural Resources Exploitation in Xinjiang.” The China Review (The Chinese University of Hong Kong) 18 (No. 2 SPECIAL THEMED SECTION: Frontiers and Ethnic Groups in China): 121-154. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26435650

[3] International Energy Agency. 2020. Data & Statistics - IEA. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics?country=CHINA&fuel=Energy%20consumption&indicator=TotElecCons.

[4] Yellinek, Roie, and Elizabeth Chen. 2019. “The “22 vs. 50” Diplomatic Split Between the West and China.” China Brief (The Jamestown Foundation) 19 (No. 22): 20-25. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://jamestown.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Read-the-12-31-2019-CB-Issue-in-PDF.pdf?x91188.

[5] United Nations General Assembly. 2019. “General Assembly official records, 74th session : 9th plenary meeting.” New York. Accessed October 18, 2020.

[6] Xu, Vicky Xiuzhong, Danielle Cave, James Leibold, Kelsey Munro, and Nathan Ruser. 2020. “Uyghurs for sale: ‘Re-education’, forced labour and surveillance beyond Xinjiang.” Policy Brief, International Cyber Policy Centre, Australian Strategic Policy Paper. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/uyghurs-sale

[7] Ibid.

[8] Xiao, Eva. 2020. Auditors to Stop Inspecting Factories in China’s Xinjiang Despite Forced-Labor Concerns. 21 September. Accessed December 2020, 16. https://www.wsj.com/articles/auditors-say-they-no-longer-will-inspect-labor-conditions-at-xinjiang-factories-11600697706.

[9] Kashyap, Aruna. 2020. Social Audit Reforms and the Labor Rights Ruse. 7 October. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/07/social-audit-reforms-and-labor-rights-ruse.

[10] Human Rights Watch. 2016. China: Passports Arbitrarily Recalled in Xinjiang. 21 November. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/11/22/china-passports-arbitrarily-recalled-xinjiang

[11] Human Rights Watch. 2020. China: Big Data Program Targets Xinjiang’s Muslims. 9 December. Accessed December 17, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/12/09/china-big-data-program-targets-xinjiangs-muslims.

[12] National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. 2020. How China's Xinjiang is tackling new COVID-19 outbreak. 29 October. Accessed November 14, 2020. http://en.nhc.gov.cn/2020-10/29/c_81994.htm.

[13] Uyghur Human Rights Proyect. 2019. “Repression Across Borders: The CCP’s Illegal Harassment and Coercion of Uyghur Americans.”

[14] Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany. 2018. Chinese Cops Now Spying on American Soil. 14 August. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://www.thedailybeast.com/chinese-police-are-spying-on-uighurson-american-soil.

[15] Allen-Ebrahimian. 2018. Chinese Police Are Demanding Personal Information From Uighurs in France. 2 March. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/03/02/chinese-police-are-secretly-demanding-personal-information-from-french-citizens-uighurs-xinjiang/.

[16] Reuters Staff. 2021. BBC World News barred in mainland China, radio dropped by HK public broadcaster. 11 February. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-britain-bbc/bbc-world-news-barred-from-airing-in-china-idUSKBN2AB214.

El yacimiento de hidrocarburos es el eje central del Plan Gas 2020-2023 del presidente Alberto Fernández, que subsidia parte de la inversión

Actividad de YPF, la compañía estatal argentina de hidrocarburos [YPF]

ANÁLISIS / Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa

Argentina enfrenta una profunda crisis económica que está impactando con toda su crudeza en el nivel de vida de sus ciudadanos. El país, que había logrado salir con enormes sacrificios del corralito de 2001, ve cómo sus mandatarios incurren en las mismas imprudencias macroeconómicas que llevaron la economía nacional al colapso. Tras un mandato enormemente decepcionante de Mauricio Macri y su “gradualismo” económico, la nueva administración de Alberto Fernández ha heredado una situación muy delicada, agravada ahora por la crisis mundial y nacional generada por la Covid-19. La deuda pública ya supone casi el 100% del PIB, el peso argentino tiene un valor inferior a 90 unidades por dólar estadounidense, mientras el déficit público persiste. La economía sigue en recesión, acumulando cuatro años de decrecimiento. El FMI, que prestó en 2018 cerca de 44.000 millones de dólares a Argentina en el mayor préstamo de la historia de la institución, ha comenzado a perder la paciencia ante la falta de reformas estructurales y las insinuaciones de reestructuración de deuda por parte del gobierno. En esta situación crítica, los argentinos observan el desarrollo de la industria petrolera no convencional como una posible salida a la crisis económica. En particular, el súper yacimiento de Vaca Muerta concentra la atención de inversores internacionales, gobierno y ciudadanos desde hace una década, siendo un proyecto muy prometedor no exento de desafíos ambientales y técnicos.

El sector energético en Argentina: una historia de fluctuaciones

El sector petrolero en Argentina tiene más de 100 años de historia desde que en 1907 se descubriera petróleo en el desierto patagónico. Las dificultades geográficas del área –escasez de agua, lejanía de Buenos Aires y vientos salinos de más de 100 km/h– hicieron que el proyecto avanzara muy lentamente hasta el estallido de la Primera Guerra Mundial. El conflicto europeo interrumpió las importaciones de carbón desde Inglaterra, que hasta la fecha constituían el 95% del consumo energético en Argentina. La emergencia del petróleo en el periodo de Entreguerras como materia prima estratégica revalorizó el sector, que comenzó a recibir enormes inversiones foráneas y domésticas en la década de los años 20. Para 1921 se creó YPF, la primera empresa petrolera estatal de América Latina, con la autosuficiencia energética como principal objetivo. La convulsión política del país durante la denominada Década Infame (1930-43) y los efectos de la Gran Depresión dañaron el incipiente sector petrolero. Los años de gobierno de Perón supusieron un tímido despegue de la industria petrolera con la apertura del sector a empresas extranjeras y la construcción de los primeros oleoductos. En 1958 llegó Arturo Frondizi a la presidencia argentina y sancionó la Ley de Hidrocarburos de 1958, logrando un impresionante desarrollo del sector en tan solo 4 años con una inmensa política de inversión pública y privada que multiplicó por tres la producción de petróleo, extendió la red de gasoductos y generalizó el acceso de industria y hogares al gas natural. El régimen petrolero en Argentina mantenía la propiedad del recurso en manos del estado, pero permitía la participación de empresas privadas y extranjeras en el proceso de producción.

Desde la exitosa década de los 60 en materia petrolera, el sector entró en un periodo de relativo estancamiento en paralelo con la caótica política y economía de Argentina en el momento. La década de los 70 supuso una compleja travesía en el desierto para YPF, sumida en una enorme deuda e incapaz de aumentar la producción y asegurar el tan ansiado autoabastecimiento.

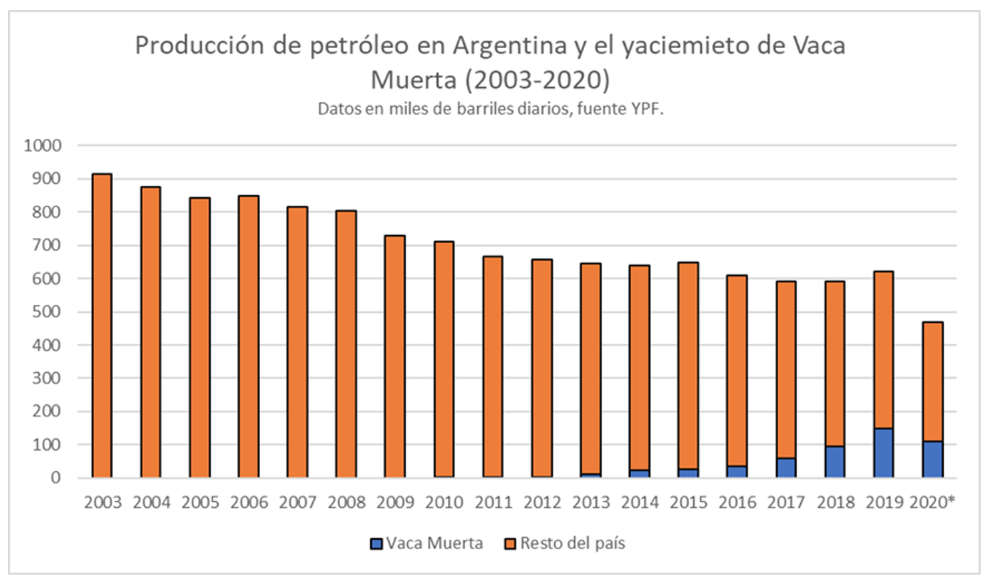

Con el denominado Consenso de Washington y la llegada a la presidencia de Carlos Menem en 1990 se procedió a la privatización de YPF y a la fragmentación del monopolio estatal sobre el sector. Para 1998, YPF ya estaba totalmente privatizada bajo la propiedad de Repsol, que controlaba el 97,5% de su capital. Fue en el periodo 1996-2003 cuando se alcanzó la producción máxima de petróleo, exportando gas natural a Chile, Brasil y Uruguay, superando además los 300.000 barriles diarios de crudo en exportaciones netas.

Sin embargo, pronto comenzó un cambio de tendencia ante la intervención estatal en el mercado. El consumo doméstico con precios fijos de venta para los productores petroleros era menos atractivo que el mercado de exportación, incentivando la sobreproducción de las compañías privadas para poder exportar petróleo e incrementar los ingresos exponencialmente. Con la subida del precio del petróleo del denominado “superciclo de las commodities” durante la primera década del presente siglo, la diferencia de precios entre las exportaciones y las ventas domésticas se acrecentó, generando un verdadero incentivo para centrar la actividad en la producción. Quedaba así la exploración en un segundo plano, ya que el consumo doméstico crecía rápidamente por los incentivos fiscales y se preveía un horizonte cercano sin posibilidad exportadora y, por ende, menores ingresos derivados del incremento en las reservas.

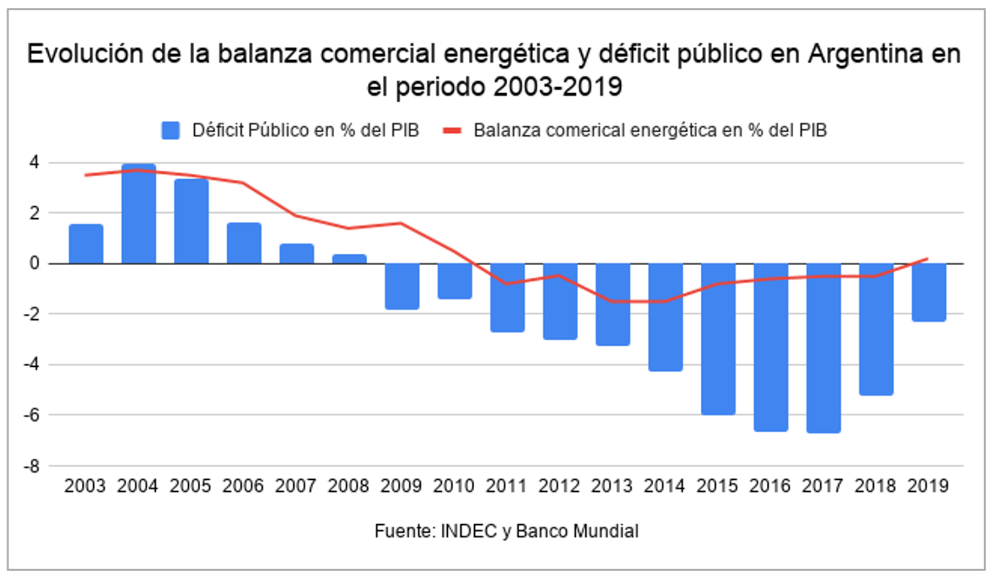

La salida a la crisis de 2001 se produjo en un contexto de superávit fiscal y comercial, que permitió recuperar la confianza de los acreedores internacionales y reducir el volumen de deuda pública. Fue precisamente, el sector energético el principal motor de esta recuperación, suponiendo más de la mitad del superávit comercial en el periodo 2004-2006 y una de las principales fuentes de ingresos fiscales de Argentina. Sin embargo, tal y como se ha mencionado, esta producción no era sostenible al existir un marco fiscal que distorsionaba los incentivos de las petroleras en favor del consumo inmediato sin invertir en exploración. Para 2004, se aplicó una nueva tarifa a las exportaciones de crudo que flotaban en función del precio internacional del mismo, alcanzando el 45% si este se situaba por encima de los 45 dólares. El enfoque excesivamente rentista de la presidencia de Néstor Kirchner terminó por dilapidar los incentivos a la inversión por parte del sector, si bien es cierto que permitieron incrementar espectacularmente los ingresos fiscales derivados, impulsando los generosos planes sociales y de pago de deuda de Argentina. Como buena muestra de esta decadencia en la exploración, en la década de 1980 se perforaban anualmente más de 100 pozos exploratorios, en 1990 la cifra superaba los 90 y para 2010 la cifra era de 26 pozos anuales. Este dato es especialmente dramático si se tiene en cuenta las dinámicas que suele seguir el sector del oil and gas, con grandes inversiones en exploración e infraestructura en épocas de precios altos, tal y como fue entre 2001-2014.

En 2011, tras una década de debates sobre el sector petrolero en Argentina, la presidenta Cristina Fernández decidía expropiar el 51% de las acciones de YPF en manos de Repsol, aduciendo razones de soberanía energética y decadencia del sector. Esta decisión seguía la línea de Hugo Chávez y Evo Morales en 2006 de incrementar el peso del Estado en el sector de los hidrocarburos en un momento de éxito electoral para la izquierda latinoamericana. La expropiación se produjo el mismo año que Argentina pasó a ser un importador neto de energía y coincidía con el descubrimiento de las grandes reservas de shale en Neuquén precisamente por YPF, hoy conocidas como Vaca Muerta. YPF en aquel momento era el productor directo de aproximadamente un tercio del volumen total de Argentina. La expropiación se produjo de forma simultánea a la imposición del “cepo cambiario”, sistema de control de capitales que hacía todavía menos atractivo la inversión privada extranjera en el sector. El país no solo no pudo recuperar el autoabastecimiento energético, sino que entro en un periodo de intensas importaciones que lastraron el acceso a dólares y produjeron buena parte del desequilibrio macroeconómico de la crisis económica actual.

La llegada de Mauricio Macri en 2015 hacía prever una nueva etapa para el sector con políticas más favorables a la iniciativa privada. Una de las primeras medidas fue establecer un precio fijo en “boca de pozo” de las explotaciones en Vaca Muerta con la idea de incentivar la puesta en marcha de los proyectos. Conforme la crisis económica se agravaba, se optó por la impopular medida de incrementar los precios de electricidad y combustibles en más de un 30%, generando un enorme descontento en el contexto de una constante devaluación del peso argentino y el encarecimiento de la vida. La cartera de Energía estuvo marcada por una enorme inestabilidad, con tres ministros diferentes que generaron enorme inseguridad jurídica al cambiar constantemente el marco regulatorio de hidrocarburos. Las renovable solar y eólica, impulsadas por un nuevo plan energético y una mayor liberalización de las inversiones lograron duplicar su aportación energética durante la estancia de Mauricio Macri en la Casa Rosada.

Los primeros años de Alberto Fernández han estado marcados por un apoyo incondicional al sector de los hidrocarburos, siendo Vaca Muerta el eje central de su política energética, anunciando el Plan Gas 2020-2023 que subsidiará parte de la inversión en el sector. Por otra parte, pese al contexto de emergencia sanitaria durante 2020 se instalaron 39 proyectos de energía renovable, con una potencia instalada de unos 1.5 GW, que supone un incremento de casi el 60% con respecto al año anterior. En cualquier caso, la continuidad de este crecimiento dependerá del acceso a divisa extranjera en el país, fundamental para poder comprar paneles y molinos eólicos del extranjero. El auge de la energía renovable en Argentina llevó a la danesa Vestas a instalar la primera planta ensambladora de molinos eólicos en el país en 2018, que ya cuenta con varias plantas productoras de paneles solares para suministrar la demanda doméstica.

Características de Vaca Muerta

Vaca Muerta no es un yacimiento desde el punto de vista técnico, se trata de una formación sedimentaria de enorme magnitud y que cuenta con depósitos dispersos de gas natural y petróleo que solo pueden explotarse con técnicas no convencionales: fractura hidráulica y perforación horizontal. Estas características hacen de Vaca Muerta una actividad compleja, que requiere atraer el máximo talento posible, especialmente de aquellos actores internacionales con experiencia en la explotación de hidrocarburos no convencionales. Igualmente, las condiciones de la provincia de Neuquén son complejas teniendo en cuenta la escasez de precipitaciones y la importancia de la industria hortofrutícola, en competición directa con los recursos hídricos que requiere la explotación de petróleo no convencional.

Desde su descubrimiento, el potencial de Vaca Muerta se comparó con el de la cuenca de Eagle Ford en Estados Unidos, productora de más de un millón de barriles diarios. Evidentemente, la región de Neuquén no cuenta ni con el ecosistema empresarial petrolero de Texas ni sus facilidades fiscales, haciendo que lo que geológicamente pudiera ser similar en la realidad haya quedado en dos historias totalmente distintas. En diciembre de 2020 Vaca Muerte produjo 124.000 barriles diarios de petróleo, cifra que se espera incremente paulatinamente a lo largo de este año para llegar a los 150.000 barriles diarios, cerca del 30% de los 470.000 barriles diarios que Argentina produjo en 2020. El gas natural sigue un proceso más lento, pendiente del desarrollo de infraestructura que permita el transporte de grandes volúmenes de gas hacia los centros de consumo y exportación. En este sentido, Fernández anunció en noviembre de 2020 el Plan de Promoción de la Producción de Gas Argentino 2020-2023 con el que la Casa Rosada busca ahorrar dólares vía la sustitución de importaciones. El plan facilita la adquisición de dólares para los inversores y mejora el precio máximo de venta del gas natural en casi un 50%, hasta los 3,70 dólares por mbtu, esperando recibir la inversión necesaria, cifrada en 6.500 millones de dólares, para alcanzar la autosuficiencia gasista. Argentina ya cuenta con capacidad para exportar gas natural a Chile, Uruguay y Brasil por medio de gasoductos. Lamentablemente, el buque flotante exportador de gas natural proveniente de Vaca Muerte abandonó Argentina a finales de 2020 tras romper YPF unilateralmente el contrato a diez años con la compañía poseedora del buque, Exmar, aduciendo dificultades económicas, limitando la capacidad de vender gas natural fuera del continente.

Una de las grandes ventajas de Vaca Muerta es la presencia de compañías internacionales con experiencia en las mencionadas cuencas de petróleo no-convencional de EEUU. La curva de aprendizaje del sector del fracking norteamericano después de 2014 está siendo aplicada en Vaca Muerta, que ha visto cómo los costes de perforación se han reducido en un 50% desde 2014 mientras ganaban en productividad. La llegada de capital norteamericano puede acelerarse si la administración de Joe Biden restringe fiscal y medioambientalmente las actividades petroleras en el país, de acuerdo con su agenda medioambientalista. En la actualidad el principal operador en Vaca Muerta tras YPF es Chevron, seguido de Tecpetrol, Wintershell, Shell, Total y Pluspetrol, en un ecosistema con 18 empresas petroleras que trabajan en diferentes bloques.

Vaca Muerta como estrategia nacional

Es evidente que alcanzar la autosuficiencia energética ayudará a los problemas macroeconómicos de Argentina, principal quebradero de cabeza de sus ciudadanos en los últimos años. No exento de riesgo medioambientales, Vaca Muerta puede ser un balón de oxígeno para un país cuya credibilidad internacional se encuentra en mínimos históricos. La narrativa pro-hidrocarburos asumida por Alberto Fernández sigue la línea de su homólogo mexicano Andrés Manual López Obrador, con quien pretende liderar un nuevo eje de izquierda moderada en Latinoamérica. El fantasma de la nacionalización de YPF por la ahora vicepresidenta Cristina Fernández, así como el reciente incumplimiento de contrato con Exmar siguen generando incertidumbre entre los inversores internacionales. Por otra parte, la mala situación financiera de YPF, principal actor en Vaca Muerta, con una deuda de más de 8.000 millones de dólares, supone un lastre importante para las expectativas petroleras del país. Igualmente, Vaca Muerta está lejos de materializar su potencial, con una producción significativa pero insuficiente para garantizar ingresos que supongan un cambio radical en la situación económica y social de Argentina. Para garantizar su éxito se necesita de un contexto de precios petroleros favorables y la llegada fluida de inversores extranjeros. Dos variables que no se pueden dar por sentadas dado el contexto político argentino y la cada vez más fuerte política de descarbonización de las empresas petroleras tradicionales.

La gran pregunta ahora es cómo compaginar el desarrollo de combustibles fósiles a gran escala con los últimos compromisos de Argentina en materia de cambio climático: reducir en un 19% las emisiones de CO2 para 2030 y alcanzar la neutralidad de carbono para 2050. Del mismo modo, la trayectoria prometedora en el desarrollo de energías renovables durante la presidencia de Mauricio Macri puede perder inercia si el sector petrolero y gasista atraen la inversión pública y privada, desplazando a la solar y eólica.

Muy probablemente Vaca Muerta avance a paso lento pero seguro conforme los precios internacionales del petróleo se vayan estabilizando al alza. La posibilidad de generar divisas y dinamizar una economía al borde del colapso no deben ser menospreciadas, pero esperar que Vaca Muerta solucione por sí sola los problemas argentinos no puede más que terminar en un nuevo episodio de frustración en el país austral.

Un acuerdo de mínimos en el último momento evita el caos de un Brexit sin acuerdo, pero se tendrán que seguir negociando flecos durante los próximos años.

Fragmento de mural sobre el Brexit [Pixabay]

ANÁLISIS / Pablo Gurbindo

Después de que el Reino Unido saliera oficialmente de la Unión Europea el 31 de enero de 2020 a medianoche, con la entrada en vigor del Acuerdo de Retirada, parecía que el asunto que ha prácticamente monopolizado el debate en Bruselas en los últimos años quedaba zanjado. Pero nada más lejos de la realidad. Se había resuelto el “Brexit político”, pero aún restaba por resolver el “Brexit económico”.

Este acuerdo dispuso para evitar el caos un periodo de transición de 11 meses, hasta el 31 de diciembre de 2020. Durante este periodo el Reino Unido, a pesar de estar ya fuera de la UE, tenía que seguir sometiéndose a la legislación europea y al Tribunal de Justicia de la UE como hasta ahora, pero sin tener voz y voto comunitario. El objetivo de esta transición era el dar tiempo a ambas partes para llegar a un acuerdo para definir la relación futura. Todas las partes sabían que en 11 meses no iba a dar tiempo. Solo un nuevo acuerdo comercial tarda años en negociarse, el acuerdo con Canadá tardó 7 años, por ejemplo. Para ello el periodo de transición incluía una posible prorroga antes del 30 de junio, pero Johnson no quiso pedirla, y prometió a sus ciudadanos tener un acuerdo comercial para el 1 de enero 2021.

Con el miedo de un posible Brexit sin acuerdo, y las graves consecuencias que tendría para las economías y ciudadanos de ambas partes, finalmente se llegó a un acuerdo el 24 de diciembre, solo una semana antes del fin del periodo de transición.

Este acuerdo entró en vigor el 1 de enero de 2021 de manera provisional, dado que en una semana no daba tiempo a que fuera aprobado. Ahora cabe preguntarse: ¿En qué consiste este acuerdo? ¿Cuáles han sido los puntos de fricción? ¿Y cuáles han sido las primeras consecuencias palpables durante estos primeros meses?

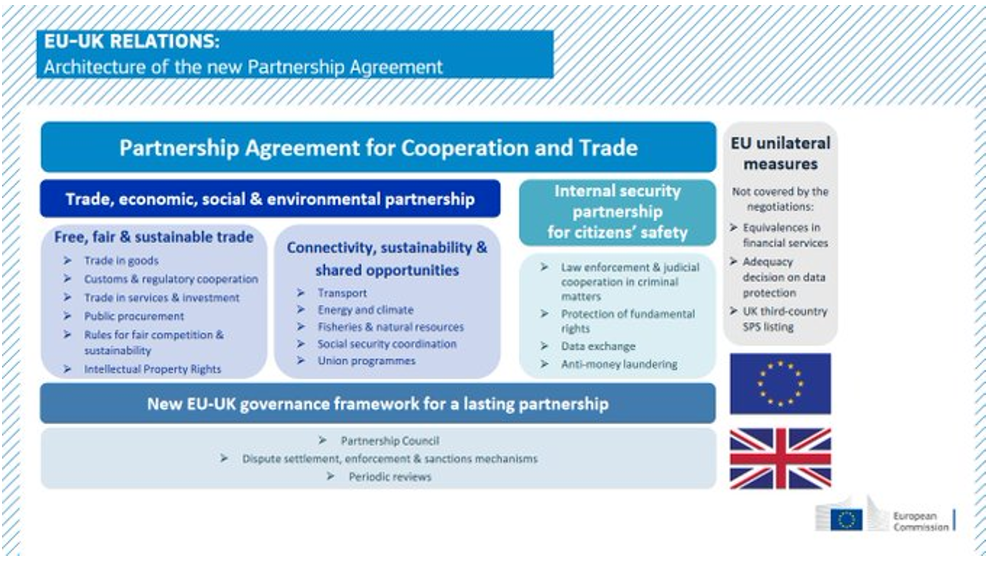

El Acuerdo de Comercio y Cooperación (ACC)

Lo que hay que dejar claro desde un principio es que este es un acuerdo de mínimos. Es un Brexit duro. Se ha evitado el Brexit sin acuerdo que hubiera sido catastrófico, pero sigue siendo un Brexit duro.

El ACC entre el Reino Unido y la Unión Europea comprende un acuerdo de libre comercio, una estrecha asociación en materia de seguridad ciudadana y un marco general de gobernanza.

Los puntos más importantes del Acuerdo son los siguientes:

Comercio de bienes

El ACC es muy ambicioso en este sentido, pues establece un libre comercio entre las dos partes sin ningún tipo de arancel o cuota a ningún producto. Si no hubiera habido acuerdo en este sentido, su relación comercial se hubiera regido por las normas de la Organización Mundial del Comercio (OMC), con sus cuotas y aranceles correspondientes. No obstante, este libre comercio tiene un pero. Esa ausencia de cualquier tipo de arancel o cuota es solo para los productos “originarios británicos”, y aquí es donde radica la complejidad.

Las reglas de origen están detalladas en el ACC, y aunque por regla general el acuerdo es generoso para calificar a un producto como “británico”, hay determinados sectores donde esta certificación será más exigente. Por ejemplo, para que un vehículo eléctrico producido en el Reino Unido y exportado a la UE evite aranceles es necesario que por lo menos el 45% de su valor añadido sea británico o europeo y que su batería sea íntegramente británica o europea. A partir de ahora demostrar el origen de cada envío en ciertos sectores va a convertirse en un infierno burocrático que antes del 31 de diciembre no existía. Y la reexportación de productos extranjeros sin transformación desde suelo británico a Europa ahora va a tener que sufrir un doble arancel: uno de entrada al Reino Unido y otro de entrada a la Unión.

Pero, aunque no existan ningún tipo de arancel o cuota en los productos, el flujo comercial habitual no se va a mantener. Por ejemplo, en el ámbito del comercio de productos agroalimentarios, la ausencia de acuerdo en el régimen sanitario y fitosanitario del Reino Unido significa que desde ahora para el comercio de estos productos van a ser necesarios certificados sanitarios que antes no lo eran. Este incremento del “papeleo” puede tener importantes consecuencias para los productos que sean más fácilmente sustituibles, pues los importadores de estos productos van a preferir ahorrarse esta burocracia extra cambiando los proveedores británicos por otros europeos.

Servicios financieros

En materia de servicios el acuerdo es bastante pobre, pero destaca la falta de acuerdo respecto de los servicios financieros, sector muy importante para el Reino Unido, que genera por sí solo el 21% de las exportaciones por servicios británicas.

Mientras el Reino Unido formaba parte de la Unión sus entidades financieras podían operar libremente en todo el territorio comunitario gracias al “pasaporte financiero”, ya que todos los Estados Miembros tienen acordadas unas normas de regulación y de supervisión de los mercados similares. Pero esto ya no aplica al Reino Unido.

El Gobierno británico decidió unilateralmente mantener el fácil acceso a sus mercados de las entidades comunitarias, pero la Unión no ha respondido recíprocamente.

Ante la ausencia de acuerdos en materia financiera, la normativa europea referida a entidades de terceros países, como regla general, sencillamente facilita a estas entidades el instalarse en la Unión para poder operar en sus mercados.

Uno de los objetivos de la UE con esta falta de reciprocidad puede haber sido el deseo de arrebatar a la City de Londres, primera plaza financiera europea, parte de su capital.

Ciudadanos

La mayor parte de este apartado quedó resuelto con el Acuerdo de Retirada, que garantizaba de por vida el mantenimiento de los derechos adquiridos (residencia, trabajo…) para los ciudadanos europeos que ya se encontraran en suelo británico, o los británicos que se encontraran en suelo europeo.

En el ACC se ha acordado la supresión de la necesidad de solicitar visado bilateralmente para estancias turísticas que no excedan los 3 meses. Para estos casos ahora será necesario llevar el pasaporte, no bastará con el documento nacional de identidad. Pero para estancias superiores se requerirán visados de residencia o de trabajo.

En cuanto al reconocimiento de titulaciones y cualificaciones profesionales y universitarias, a pesar del interés del Reino Unido de que se mantuvieran de forma automática como hasta ahora, la UE no lo ha permitido. Esto podría suponer por ejemplo que profesionales titulados como abogados o enfermeros tengan más dificultades para que se les reconozca su título y puedan trabajar.

Protección de datos y cooperación en seguridad

El acuerdo va a permitir mantener la cooperación policial y jurídica, pero no con la misma intensidad que antes. El Reino Unido ya no formará parte de las bases de datos comunitarias sobre estos asuntos. Los intercambios de información solo se harán a instancia de parte, ya sea solicitando información como enviando por iniciativa propia.

Las relaciones británicas con Europol (Oficia Europea de Policía) o con Eurojust (Agencia europea para la cooperación judicial) se mantendrán, pero como colaboración externa.

Participación en programas de la Unión

El Reino Unido seguirá formando parte de algunos programas comunitarios como: Horizon, principal programa de cooperación científica europea; Euratom, a través de un acuerdo de cooperación externo al ACC; ITER, un programa internacional para el estudio de la energía de fusión; Copernicus, un programa dirigido por la Agencia Espacial Europea para el desarrollo de la capacidad autónoma y continua de observación terrestre; y SST (Space Surveillance and Tracking) un programa europeo de rastreo de objetos espaciales para evitar su colisión.

Pero por otro lado el Reino Unido no continuará en otros programas, destacando el importante programa de intercambio estudiantil Erasmus. Johnson ya ha anunciado la creación de un programa nacional de intercambio estudiantil que llevará el nombre del matemático británico Alan Turing, que descifro el código Enigma durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial.

Puntos de fricción en la negociación

Ha habido ciertos puntos que por su complejidad o simbolismo han sido los principales puntos de fricción entre la Unión y el Reino Unido. Incluso han puesto en jaque el éxito de las negociaciones. Los tres principales baches para la negociación han sido: la pesca, el “level-playing field” y la gobernanza.

Sorprende la desmesurada importancia que ha tenido la pesca sobre la negociación, teniendo en cuenta que solo representa el 0,1 % del PIB británico, y no es un sector esencial tampoco para la UE. Su importancia radica en su valor simbólico, y la importancia que le han dado los partidarios del Brexit como ejemplo de recuperación de la soberanía perdida. También hay que tener en cuenta que es uno de los puntos en los que el Reino Unido partía con ventaja en las negociaciones. En las aguas británicas se encuentran algunos de los principales caladeros de Europa, que han venido representando el 15% del total de la pesca europea. De estos caladeros el 57% se lo llevaban los 27, y el 43% restante se lo llevaban los pescadores británicos. Porcentaje que enfurecía mucho al sector pesquero británico, que ha sido uno de los principales sectores que apoyaron el Brexit.

La intención británica era negociar anualmente las cuotas de acceso a sus aguas, siguiendo el ejemplo que tiene Noruega con la UE. Pero finalmente se ha acordado un recorte del 25% de las capturas de forma progresiva, pero manteniendo el acceso a aguas británicas. Este acuerdo estará en vigor durante los próximos cinco años y medio, a partir de entonces serán necesarias nuevas negociaciones que serán entonces anuales. A cambio, la UE se ha guardado la posibilidad de represalias comerciales en el caso de que se deniegue el acceso a las aguas británicas a los pescadores europeos.

“Level-playing field”

El tema de la competencia desleal era uno de los temas que más preocupaban en Bruselas. Dado que a partir de ahora los británicos no tienen que seguir la legislación europea, existía la preocupación de que, a apenas unos kilómetros de la Unión, un país del tamaño y peso del Reino Unido redujera considerablemente sus estándares laborales, medioambientales, fiscales o de ayudas públicas. Esto podría provocar que muchas empresas europeas decidieran trasladarse al Reino Unido por esta reducción de estándares.

El acuerdo establece un mecanismo de vigilancia y de represalias en casos de discrepancias si una de las partes se siente perjudicada. Si hay un conflicto, dependiendo del caso, se someterá a un panel de expertos, o se someterá a arbitraje. Para la UE hubiera sido preferible un sistema donde las compensaciones arancelarias fueran automáticas y si no interpretadas por el TJUE. Pero para el Reino Unido uno de sus principales objetivos en la negociación era no estar bajo la jurisdicción del TJUE de ninguna forma.

Gobernanza

El diseño de la gobernanza del acuerdo es complejo. Está presidido por el Consejo de Asociación Conjunto que garantizará que el ACC se aplique e interprete correctamente, y en el que se debatirán todas las cuestiones que puedan surgir. Este consejo será ayudado por más de treinta comités especializados y grupos técnicos.

Si surge una disputa se acudirá a este Consejo de Asociación Conjunto. Si no se alcanza una solución por mutuo acuerdo se acudirá entonces a un arbitraje externo cuya resolución es vinculante. En caso de incumplimiento, la parte perjudicada está autorizada para tomar represalias.

Este instrumento permite a la UE cubrirse las espaldas ante el riesgo del Reino Unido de incumplir parte del acuerdo. Este riesgo ganó mucha fuerza durante las negociaciones, cuando Johnson presentó ante el Parlamento británico la Ley de Mercado Interior, que pretendía evitar cualquier tipo de aduana interior en el Reino Unido. Esta ley iría en contra de la “salvaguarda irlandesa” acordada por el propio Johnson y la UE en el Acuerdo de Retirada, e iría contra el derecho internacional como contravención clara al principio del “pacta sunt servanda”. Al final esta ley no se tramitó, pero creo gran tensión entre la UE y el Reino Unido, en la oposición británica a Johnson e incluso entre sus propias filas al poner la credibilidad internacional del país en tela de juicio.

Consecuencias

Durante estos primeros meses de entrada en vigor del ACC ya se han podido ver varias consecuencias importantes.

La polémica retirada del Renio Unido del programa Erasmus ya se ha hecho notar. Según las universidades británicas, las solicitudes de estudios de ciudadanos europeos han disminuido un 40%. La pandemia ha tenido que ver en esa importante reducción, pero hay que tener en cuenta también que las tasas universitarias en el Reino Unido tras la salida del programa han aumentado por cuatro.

Respecto a los servicios financieros, la City de Londres ya ha perdido durante estos primeros meses el título de principal centro financiero europeo en favor de Ámsterdam. Los intercambios diarios de acciones en enero en Ámsterdam sumaron 9.200 millones de euros, superior a los 8.600 millones de euros gestionados por la City. La media londinense el año pasado fue de 17.500 millones de euros, muy superior a la segunda plaza europea que fue Fráncfort, con una media de 5.900 millones de euros. El año pasado la cifra media de intercambios de Ámsterdam fue de 2.600 millones de euros, lo que la situaban como sexta plaza financiera europea. La falta de reciprocidad de la UE respecto a los servicios financieros ha podido cumplir su objetivo por ahora.