Breadcrumb

Blogs

Entries with Categorías Global Affairs Unión Europea .

Pekín acelera su cambio de estrategia económica mientras Alemania intenta reinventarse como potencia manufacturera con su 'Industry 4.0'

De ser la gran fábrica de los productos más bajos en la cadena mundial de precios a convertirse en una potencia manufacturera apreciada por el valor añadido que China pueda aportar a su producción. El plan 'Made in China 2025' está en marcha con el propósito de operar el cambio en unas pocas décadas. El empuje chino pretende ser contrarrestado por Alemania con su 'Industry 4.0', para preservar el reconocimiento internacional a lo producido por la industria germana.

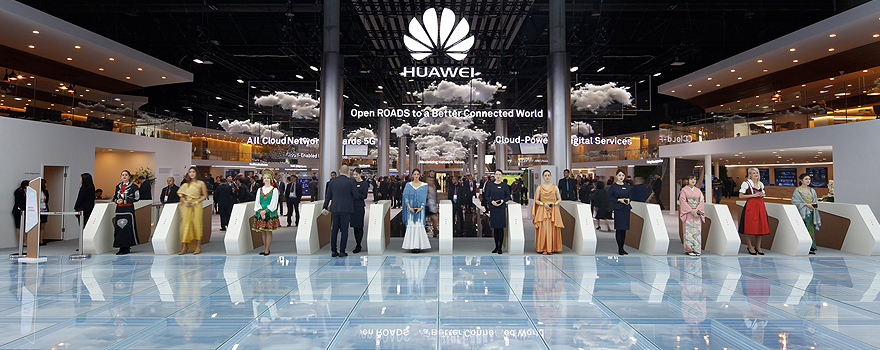

▲ Stand de Huawei en el Mobile World Congress 2017 [Huawei]

ARTÍCULO / Jimena Puga

“Made in China 2025” es un plan político-económico presentado por el primer ministro chino Li Keqiang en mayo de 2015. El principal objetivo de esta iniciativa es el crecimiento de la industria China, y a su vez fomentar el desarrollo industrial en las áreas más pobres de China situadas en el interior del país, como las provincias de Qinghai, Sinkiang o Tíbet. Una de las metas es aumentar el contenido nacional de los materiales básicos hasta un 40% para 2020 y un 70% para 2025.

Pero, ¿qué quiere conseguir la República Popular con esta iniciativa? Tal y como anunciaba Mu Rongping, director general del Centro de Innovación y Desarrollo de la Academia China de Ciencia, “no creo que el plan Made in China 2025 y otros planes relacionados con la industria supongan una amenaza para la economía mundial y la innovación. Estas políticas industriales dimanan de la cultura tradicional china. En China siempre que establecemos una nueva medida política o económica tenemos las expectativas altas. Así, si conseguimos solo la mitad, estaremos satisfechos. Este punto de vista ha llevado a China al cambio y hasta cierto punto, a la innovación”.

Evolución económica china

En 1978 Deng Xiaoping llegó al poder y cambió todas las estructuras maoístas. Así, desde una perspectiva económica, el Derecho se ha convertido en un elemento decisivo para resolver conflictos y mantener el orden social en China. Deng trató de instaurar un sistema socialista, pero con “características chinas”. De esta forma se justificó una economía de libre mercado y, en consecuencia, la obligación de desarrollar nuevas normas y estructuras. Además, el presidente introdujo el concepto de democracia como un instrumento necesario para la nueva China socialista. La reforma legal más importante fue la posibilidad de crear negocios privados. En 1992 se adoptó la expresión de una “economía de mercado socialista”, una etiqueta para esconder un capitalismo real (1).

El actual presidente de la República Popular, Xi Jinping, se ha manifestado contrario al proteccionismo económico y a favor de equilibrar la globalización para “hacerla más incluyente y equitativa”. También añadió un aumento en el estudio del capitalismo actual y el desarrollo del socialismo con características chinas propio del país, ya que si el partido abandonase el marxismo perdería “su alma y dirección”, además de calificarlo como “irreemplazable para comprender y transformar el mundo”.

El plan Made in China 2025 y el Industry 4.0

Durante esta última década, China ha emergido como uno de los milagros manufactureros más relevantes de la historia desde que empezase la Revolución Industrial en Gran Bretaña en el siglo XVIII. A finales de 2012, China se convirtió en un líder global en operaciones de manufacturas y en la segunda potencia económica del mundo por encima de Alemania. El paradigma Made in China ha sido evidenciado por productos hechos en China, desde productos de alta tecnología como ordenadores o teléfonos móviles hasta bienes de consumo como aires acondicionados. El objetivo del Imperio del Centro es extender este plan a tres fases. En la primera, del año 2015 al año 2025, China pretende figurar en la lista de potencias manufactureras globales. En la segunda, de 2026 a 2035, China prevé posicionarse en un nivel medio en cuanto a poder manufacturero mundial. Y por último, en la tercera fase, de 2036 a 2049, año en que la República Popular celebrará su centenario, China desea convertirse en el país manufacturero líder del mundo.

En 2013, Alemania, un país mundialmente líder en cuanto a industrialización, publicó su plan estratégico Industry 4.0. Conocido por sus marcas prestigiosas como Volkswagen o BMW, las industrias líderes del país han enfatizado su fuerza innovadora que les permite reinventarse una y otra vez. El plan Industry 4.0 es otro ejemplo de la estrategia manufacturera del país germano para competir en una nueva revolución industrial basada en la integración industrial, en la integración de la información industrial, Internet y la inteligencia artificial. Alemania es mundialmente conocida por el diseño y calidad de sus productos. El plan Industry 4.0, presentado en 2013 por el Gobierno alemán, se centra en la smart factory, es decir, que las fábricas del futuro sean más sostenibles e inteligentes; en sistemas ciberfísicos, que integran tecnologías avanzadas como la automoción, el intercambio de datos en la tecnología de manufacturación y la impresión 3D, y en las mercancías y las personas.

Ambos planes, Industry 4.0 y Made in China 2025 se centran en la nueva revolución industrial y emplean elementos de digitalización manufacturera. El núcleo del plan alemán es el sistema ciberfísico, es decir un mecanismo controlado o monitorizado por algoritmos estrechamente ligados a Internet y a sus usuarios, y la integración en mecanismos de creación de valor dinámico. El plan chino, además del plan de acción “Internet Plus Industry”, tiene un objetivo fijado especialmente en la consolidación de las industrias existentes, en el fomento de la diversidad y la ampliación del margen de actuación de numerosas industrias, realzando la cooperación regional mediante el uso de Internet para una manufacturación sin fronteras, la innovación de nuevos productos y la mejora en la calidad de los mismos.

En 2020 Estados Unidos será el país más competitivo en cuanto a manufacturación del mundo, seguido por China, Alemania, Japón, India, Corea del Sur, México, Taiwán, Canadá y Singapur. De estos diez países, seis son países asiáticos, uno europeo y los tres restantes miembros del NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement).

Este nuevo giro en la estrategia industrial se traduce en una anticipación del mundo a una cuarta revolución industrial propiciada por los avances tecnológicos. China será sin duda uno de los líderes internacionales de esta revolución gracias a los planes Made in China 2025 y One Belt One Road, sin embargo, las nuevas economías emergentes como Sudáfrica, Vietnam o Hungría que han contribuido a la economía mundial en los últimos años requerirán más atención.

(1) Vid. ARANZADI, Iñigo González Inchaurraga, Derecho Chino, 2015, p. 197 y ss.

En un contexto de creciente populismo, el pulso entre Bruselas y Roma es decisivo para el futuro de la UE

En una medida sin parangón dentro de la historia de la Unión, la Comisión Europea ha desestimado los presupuestos nacionales presentados por el Gobierno populista italiano, por no tender a los objetivos de déficit marcados. Ni Bruselas ni Roma parecen tener la intención de abandonar sus posturas, por lo que un enfrentamiento institucional amenaza el horizonte europeo.

▲ Giuseppe Conte, presidente del Gobierno italiano, con los vicepresidentes Luigi di Maio (izqda.), líder del Movimiento 5 Estrellas, y Mateo Salvini (dcha.), líder de la Liga Norte [Gob. de Italia]

ARTÍCULO / Manuel Lamela

Tras siete meses en el Gobierno, la coalición formada por el Movimiento 5 Estrellas y La Liga Norte han cumplido con lo prometido e iniciado, con la presentación del presupuesto de la república italiana, un proceso de enfrentamiento y desafío con la Unión Europea (UE). Las autoridades de Bruselas acusan a Italia de romper, con sus irresponsabilidades, los lazos de confianza que forjan y dan sentido al proyecto europeo.

El pasado día 16 de octubre el ejecutivo de Giuseppe Conte presentó un presupuesto con una previsión de déficit del 2,4%; si bien es cierto que la cifra está por debajo del límite del 3% fijado por la normativa europea, triplica lo pactado anteriormente entre Roma y la UE. Además, si la deuda pública de Italia es del 131% del PIB, lo que la convierte en la segunda más alta de la Unión monetaria, solamente superada por Grecia, el nuevo presupuesto no hará más que aumentarla, ya que pretende incrementar de forma significativa el gasto público.

El aumento del gasto parece obedecer a los intereses populistas del líder de la Liga Norte y ministro del Interior, Mateo Salvini, quien no ha ocultado su intención de buscar apoyo en los sectores más fracturados de la sociedad italiana. Cultivar el victimismo frente a Europa puede dar un cierto rédito político, pero el ejemplo de Grecia nos muestra que actitudes de ese tipo suelen acabar en tragedia, debilitando sobremanera al Estado ante otra posible crisis de deuda.

La Comisión Europea rechazó a finales de octubre el borrador presupuestario italiano –devolver el presupuesto de un Estado miembro era un acto sin precedentes– e instó a Roma a enviar una versión revisada en un plazo máximo de tres semanas. La decisión no cierra las puertas al diálogo y a las negociaciones, como indica en su explicación de lo sucedido el comisario de Asuntos Económicos, Pierre Moscovici; “El dictamen adoptado hoy no debería sorprender a nadie, ya que el proyecto de presupuesto del Gobierno italiano representa una desviación clara e intencional de los compromisos asumidos por Italia el pasado mes de julio. Sin embargo, nuestra puerta no está cerrada. Queremos continuar nuestro diálogo constructivo con las autoridades italianas. Celebro el compromiso del ministro de Finanzas, Giovanni Tria, con este fin y debemos avanzar con este espíritu en las próximas semanas”.

Pero desde el Gobierno de Conte se asegura que no existe un plan B y que no hay ninguna posibilidad de que Italia dé un paso atrás. Tanto Mateo Salvini como el líder del Movimiento 5 Estrellas, Luigi di Maio, ambos vicepresidentes del Gobierno, defendieron la postura Italiana y atacaron a Bruselas alegando que es normal que esta se encuentre descontenta, ya que es la primera vez que Italia se libera de las garras del eurogrupo a la hora de decidir su política económica. También manifestaron que, con su respuesta, el colegio de Comisarios ataca directamente al pueblo Italiano. Y acusaron al presidente de la Comisión, Jean-Claude Juncker, de “solo hablar con gente embriagada”, algo que sin duda muestra poco respeto hacia las instituciones.

La táctica de simular fortaleza y determinismo, que ambas formaciones políticas italianas usaron durante la campaña electoral, se está viendo correspondida por el resto de líderes europeos con un ejercicio de poder real. La petición del ministro italiano de Finanzas, Giovanni Tria, para que Italia pueda gozar de la misma oportunidad que contó Portugal en el pasado, cuando Bruselas aceptó que el primer ministro luso, Antonio Costa, no aplicara el volumen de recortes deseado desde la Comisión, se verá ahogada por las imprudentes formas que emplean los líderes políticos de la República Italiana.

Si Italia se niega a seguir las recomendaciones dadas por la UE cabe la posibilidad de que la Comisión se plantee imponer multas, que pueden llegar a suponer un 0.2% del PIB, por el incumpliendo del pacto de Estabilidad y Crecimiento. Pero al margen de las sanciones la UE no posee derecho a veto ni dispone tampoco de ninguna otra competencia para evitar la entrada en vigor del presupuesto italiano. Como indican diversos expertos, será la presión de los mercados la que haga corregir la medida italiana, evitando así un enfrentamiento directo entre Roma y Bruselas que dañaría a ambas partes por igual. Los analistas de Goldman Sachs predicen que “la deuda italiana debe empeorar para ejercer la presión adecuada y obligar a que el Gobierno opte por otra retórica”.

Aunque la Comisión Europea logre evitar una confrontación con Italia, sí podrá verse expuesta a la campaña de victimismo de las agrupaciones populistas italianas, táctica que ya emplearon con éxito en las pasadas elecciones. Se trata de una táctica que no es de creación italiana, pues desde la crisis del año 2008 diversas agrupaciones y partidos surgieron con una postura claramente contraria a Bruselas, acusando a las instituciones comunitarias de todos los males que sufren las sociedades europeas. Ejemplos hay varios; quizás el Brexit sea el más sonado dada su relevancia a nivel europeo e internacional, pero no nos debemos olvidar del ascenso de formaciones como el Frente Nacional en Francia, el Partido de la Libertad en Austria o Podemos en España, partido este último que tuvo su gran lanzamiento público a raíz de las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo de 2015.

Hasta el momento en Europa no se ha conseguido encontrar la manera de evitar o neutralizar las campañas de demagogia que proliferan en la Europa actual. Aunque se están realizando ciertos avances en cuanto al poder comunicativo de la UE, es incomprensible que desde Bruselas no se consiga explicar con eficacia el proyecto europeo a los ciudadanos de la Unión. Se trata de una carencia que el proyecto europeo arrastra desde su nacimiento y que ha sido causa de muchos de los males que han afectado a la unidad regional en las últimas décadas. En este caso Europa tiene que aportar datos que resulten sencillos de comprender para el ciudadano medio italiano y que le hagan ver que las medidas adoptadas por su Gobierno serán dañinas para la sociedad italiana en un futuro próximo, por mucho que se encuentren edulcoradas por mensajes que responden a promesas vacías y políticas mesiánicas.

Otro de los factores que preocupan en el seno de la Comisión es el riesgo de contagio del virus generado dentro de la tercera economía de la UE (descontando ya el Reino Unido). En un principio puede parecer posible que otros Estados miembros se sientan atraídos a seguir los pasos de Italia; sin embargo, las autoridades europeas dicen creer firmemente que su dura respuesta a Roma reforzará la unión monetaria e incluso hará que aumente la integridad en ámbitos como la unidad bancaria. En cuanto al exterior, la decisión mostrará que el rigor presupuestario comunitario se cumple, generando confianza y seguridad en los mercados, y por último demostrando que no se da tregua a las formaciones populistas dentro de Europa.

Did the Provisional IRA lose its ‘Long War’? Why are dissident Republicans fighting now?

ESSAY / María Granados Machimbarrena

In 1998, the Belfast Agreement or Good Friday Agreement marked the development of the political relations between Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom. Several writers, politicians and academics claimed the British had won the ‘Long War’.(1)

However, according to other scholars and politicians(2), the armed struggle has not left the region. The following paper delves into the question as to whether the war is over, and attempts to give an explanation to the ultimate quest of dissident Republicans.

On the one hand, Aaron Edwards, a scholar writing on the Operation Banner and counter- insurgency, states that Northern Ireland was a successful peace process, a transformation from terrorism to democratic politics. He remarks that despite the COIN being seen as a success, the disaster was barely evaded in the 1970s.(3) The concept of ‘fighting the last war’, meaning the repetition of the strategy or tactic that was used to win the previous war(4), portrays Edward’s critique on the Operation. The latter was based on trials and tests undertaken in the post-war period, but the IRA also studied past interventions from the British military. The insurgents’ focus on the development of a citizen defence force and the support of the community, added to the elusive Human Intelligence, turned the ‘one-size-fits-all’ British strategy into a failure. The British Army thought that the opponents’ defeat would bring peace, and it disregarded the people-centric approach such a war required. The ‘ability to become fish in a popular sea’, the need to regain, retain and build the loyalty and trust of the Irish population was the main focus since 1976, when the role of the police was upgraded and the Army became in charge of its support. The absence of a political framework to restore peace and stability, the lack of flexibility, and the rise of sectarianism, a grave socio-economic phenomenon that fuelled the overall discontent, could have ended on a huge disaster. Nonetheless, Edwards argues the peace process succeeded because of the contribution of the Army and the political constraints imposed to it.(5)

In 2014, writer and veteran journalist Peter Taylor claimed that the British had won the war in Northern Ireland. He supported his statement through two main arguments: the disappearance of the IRA and the absence of unity between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Former Minister Peter Robinson (DUP Party) firmly rejected the idea of such a union ever occurring: ‘It just isn't going to happen’. Ex-hunger striker Gerard Hodgins was utterly unyielding in attitude, crying: ‘We lost. (...) The IRA are too clever to tell the full truth of what was actually negotiated. And unionists are just too stupid to recognise the enormity of what they have achieved in bringing the IRA to a negotiated settlement which accepts the six-county state.’ They were all contested by Sinn Fein President Gerry Adams, a political fighter and defender of a united Ireland, and Hutchinson, who stated that the republicans were fighting a cultural battle to eradicate Britishness. He agreed that the war had changed in how it was being fought, “but it is still a war” he concluded.(6) Former IRA commander McIntyre disagrees, in his book he suggests that the PIRA(7) is on its death bed. So is the army council that plotted its campaign. ‘If the IRA ever re-emerges, it will be a new organisation with new people’.(8)

There is an important point that most of the above-mentioned leaders fail to address: the so- called cultural battle, which is indeed about the conquest of ‘hearts and minds’. Scholars(9) find there is a deep misunderstanding of the core of republicanism among politicians and disbelievers of the anti-GFA groups’ strength. In fact, there has been an increase on the number of attacks, as well as on the Provisional movement’s incompetence. Historical examples show that the inability to control the population, the opponent’s motivation, or the media leads to defeat. E.g.: C.W. Gwynn realised of the importance of intelligence and propaganda, and H. Simson coined the term ‘sub-war’, or the dual use of terror and propaganda to undermine the government.(10) T.E. Lawrence also wrote about psychological warfare. He cited Von der Goltz on one particular occasion, quoting ‘it was necessary not to annihilate the enemy, but to break his courage.’(11)

On the other hand, Radford follows the line of Frenett and Smith, demonstrating that the armed struggle has not left Northern Ireland. There are two main arguments that support their view: (1) Multiple groups decline the agreement and (2) Social networks strengthen a traditional-minded Irish Republican constituency, committed to pursue their goals.

In the aftermath of the GFA, the rejectionist group PIRA fragmented off and the RIRA was born. The contention of what is now called RIRA (Real IRA) is that such a body should always exist to challenge Great Britain militarily. Their aim is to subvert and to put an end to the Peace Process, whilst rejecting any other form of republicanism. Moreover, their dual strategy supported the creation of the political pressure group 32CSM.(12) Nonetheless, after the Omagh bombing in 1998, there was a decline in the military effectiveness of the RIRA. Several events left the successor strategically and politically aimless: A new terrorism law, an FBI penetration, and a series of arrests and arms finds.(13) In spite of what seemed to be a defeat, it was not the end of the group. In 2007, the RIRA rearmed itself, an on-going trend that tries to imitate PIRA’s war and prevents the weaponry from going obsolete. In addition, other factions re-emerged: The Continuity IRA (CIRA), weaker than the RIRA, was paralysed in 2010 after a successful penetration by the security forces. Notwithstanding, it is still one of the richest organisations in the world. Secondly, the Oglaigh na hEireann (ONH) is politically aligned with the RSF and the RNU. They have not been very popular on the political arena, but they actively contest seats in the council.(14)

In 2009, the Independent Monitoring Commission acknowledged an increase in ‘freelance dissidents’, who are perceived as a growing threat, numbers ranging between 400-500. The reason behind it is the highly interconnected network of traditional republican families. Studies also show that 14% of nationalists can sympathetically justify the use of republican violence. Other factors worth mentioning include: A growing presence of older men and women with paramilitary experience; an increase of coordination and cooperation between the groups; an improvement in capability and technical knowledge, evidenced by recent activities.(15)

In 2014, a relatively focused and coherent IRA (‘New IRA’) emerged, with poor political support and a lack of funding, but reaching out to enough irredentists to cause a potential trouble in a not so distant future.

Conclusion

Von Bülow predicted: ‘[Our consequence of the foregoing Exposition, is, that] small States, in the future, will no more vanquish great ones, but on the contrary will finally become a Pray to them”.(16) One could argue that it is the case with Northern Ireland.

Although according to him, number and organisation are essential to an army,(17) the nature of the war makes it difficult to fight in a conventional way.(18) Most documents agree that the war against the (P)IRA must be fought with a counterinsurgency strategy, since, as O’Neill thoughtfully asserts, ‘to understand most terrorism, we must first understand insurgency.’ In the 1960s, such strategies began to stress the combination of political, military, social, psychological, and economic measures.(19) This holistic approach to the conflict would be guided by political action, as many scholars put forward in counterinsurgency manuals (e.g.: Galula citing Mao Zedong’s ‘[R]evolutionary war is 80 per cent political action and only 20 per cent military’.(20) Jackson suggests that the target of the security apparatus may not be the destruction of the insurgency, but the prevention of the organisation from configuring its scenario through violence. Therefore, after the security forces dismantle the PIRA, a larger and more heavy response should be undertaken on the political arena to render it irrelevant.(21)

One of the main dangers such an insurgency poses to the UK in the long term is the re-opening of the revolutionary war, according to the definition given by Shy and Collier.(22) Besides, the risks of progression through repression is its reliance on four fragile branches, i.e.: Intelligence, propaganda, the secret services and the police.(23) The latter’s coordination was one of the causes of the fall of the PIRA, as aforementioned, and continues to be essential: ‘(...) these disparate groups of Republicans must be kept in perspective and they are unlikely, in the short term at least, to wield the same military muscle as PIRA (...), and much of that is due to the efforts of the PSNI, M15 and the British Army’ maintains Radford. Thus, ‘Technical and physical intelligence gathering are vital to fighting terrorists, but it must be complemented by good policing’.

Hence, unless the population is locally united; traditional, violent republican ideas are rejected, and the enemy remains fragmented, the remnants of the ‘Long War’ are likely to persist and cause trouble to those who ignore the current trends. There is an urgent need to understand the strong ideology behind the struggle. As the old Chinese saying goes: ‘It is said that if you know your enemies and know yourself, you will not be imperilled in a hundred battles’.(24)

1. Writer and veteran journalist Peter Taylor, Former Minister Peter Robinson (DUP Party), ex-IRA hunger striker Gerard Hodgins, and former IRA commander and Ph.D. Anthony McIntyre.

2. M. Radford, Ross Frenett and M.L.R. Smith, as well as PUP leader Billy Hutchinson and Sinn Fein President Gerry Adams.

3. Edwards, Aaron. “Lessons Learned? Operation Banner and British Counter-Insurgency Strategy” International Security and Military History, 116-118.

4. Greene, Robert, The 33 Strategies of War. Penguin Group, 2006.

5. Edwards, Aaron. l.c.

6. Who Won the War? [Documentary]. United Kingdom, BBC. First aired on Sep 2014.

7. Provisional IRA

8. McIntyre, Anthony. Good Friday: The Death of Irish Republicanism, 2008.

9. E.g.: R. Frenett, M. L. R. Smith.

10. Pratten, Garth. “Major General Sir Charles Gwynn: Soldier of the Empire, father of British counter- insurgency?” International Security and Military History, 114-115.

11. Lawrence, T. E. Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Triumph. New York: Anchor, 1991.

12. ‘The 32 County Sovereignty Movement’

13. For instance, Freddie Scappatticci, the IRA’s head of internal security, was exposed as a British military intelligence agent in 2003.

14. Radford, Mark. ‘The Dissident IRA: Their “War” Continues’ The British Army Review 169: Spring/ Summer 2017, 43-49 f.f.

15. ‘Terrorists continue to plot, attack and build often ingenious and quite deadly devices’ Ibidem.

16. Von Bülow, Dietrich Heinrich. ‘The Spirit of the Modern System of War’. Chapter I, P. 189. Cambridge University Press, Published October 2014.

17. Von Bülow, D.H., l.c. P. 193 Chapter II.

18. Indeed, some authors will define it as an ‘unconventional war’. E.g.: ‘revolutionary war aims at the liquidation of the existing power structure and at a transformation in the structure of society.’ Heymann, Hans H. and Whitson W. W., ‘Can and Should the United States Preserve A Military Capability for Revolutionary Conflict?’ Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, Ca., 1972, p. 5.p. 54.

19. O’Neill, Board E. Insurgency and Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse. Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, 2005. Chapter 1: Insurgency in the Contemporary World.

20. Galula, David. Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice. London: Praeger, 1964.

21. Jackson, B. A., 2007, ‘Counterinsurgency Intelligence in a “Long War”: The British Experience in Northern Ireland.’ January-February issue, Military Review, RAND Corporation.

22. ‘Revolutionary War refers to the seizure of political power by the use of armed force’. Shy, John and Thomas W. Collier. “Revolutionary War” in Peter Paret, ed. Makers of Modern Strategy: From Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1986.

23. Luttwak, Edward. (2002). Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace. Cambridge, US: Belknap Press.

24. Sun Tzu. The Art of War. Attack By Stratagem 3.18.

Bibliography

Edwards, Aaron. Lessons Learned? Operation Banner and British Counter-Insurgency Strategy International Security and Military History, 116-118.

Galula, David. Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice. London: Praeger, 1964.

Greene, Robert. The 33 Strategies of War. Penguin Group, 2006.

Heymann, Hans H. and Whitson W. W.. Can and Should the United States Preserve A Military Capability for Revolutionary Conflict? (Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, Ca., 1972), p. 5.p. 54.

International Monitoring Commission (IMC), Irish and British governments report on the IRA army council’s existence, 2008.

Lawrence, T. E. Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Triumph. New York: Anchor, 1991.

Luttwak, Edward. Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace. Cambridge, US: Belknap Press, 2002.

McIntyre, Anthony. Good Friday: The Death of Irish Republicanism, 2008.

O’Neill, Board E.. Insurgency and Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse. Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, 2005.

Pratten, Garth. Major General Sir Charles Gwynn: Soldier of the Empire, father of British counter-insurgency? International Security and Military History, 114-115.

Radford, Mark. The Dissident IRA: Their ‘War’ Continues The British Army Review 169: Spring/Summer 2017, 43-49.

Ross Frenett and M.L.R. Smith. IRA 2.0: Continuing the Long War—Analyzing the Factors Behind Anti-GFA Violence, Published online, June 2012.

Sepp, Kalev I.. Best Practices in Counterinsurgency. Military Review 85, 3 (May-Jun 2005), 8-12.

Sun Tzu, S. B. Griffith. The Art of War. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964. Print.

Taylor, Peter. Who Won the War? [Documentary]. United Kingdom, BBC. First aired on Sep 2014.

Thompson, Robert. Defeating Communist Insurgency. St. Petersburg, FL: Hailer Publishing, 2005.

Von Bülow, Dietrich Heinrich. The Spirit of the Modern System of War. Cambridge University Press, Published October 2014.

WORKING PAPER / Marianna McMillan

ABSTRACT

In appearance the internet is open and belongs to no one, yet in reality it is subject to concentrated tech firms that continue to dominate content, platform and hardware. This paper intends to highlight the importance in preventing any one firm from deciding the future, however this is no easy feat considering both: (i) the nature of the industry as ambiguous and uncertain and (ii) the subsequent legal complexities in defining the relevant market to assess and address their dominance without running the risk of hindering it. Thus, the following paper tries to fill the gap by attempting to provide a theoretical and practical examination of: (1) the nature of the internet; (2) the nature of monopolies and their emergence in the Internet industry; and (3) the position of the US in contrast to the EU in dealing with this issue. In doing so, this narrow examination illustrates that differences exist between these two regimes. Why they exist and how they matter in the Internet industry is the central focus.

Download the document [pdf. 387K]

Download the document [pdf. 387K]

ESSAY / Blake Bierman

The Common Foreign, Security, and Defense Policy (CFSDP) of the European Union today acts a chameleonic hybrid of objectives and policies that attempt to resolve a plethora of threats faced by the EU. In a post 9/11 security framework, any acting policy measure must simultaneously answer to a wide array of political demands from member states and bureaucratic constraints from Brussels. As a result, the urgent need for consolidation and coherency in a common, digestible narrative has evolved into a single EU Global Strategy that boldly attempts to address today’s most pressing security whilst proactively deterring those of tomorrow. In this analysis, I will first present a foundational perspective on the external context of the policy areas. Next, I will interpret the self-perception of the EU within such a context and its role(s) within. Thirdly, I will identify the key interests, goals, and values of the EU and assess their incorporation into policy. I will then weigh potential resources and strategies the EU may utilize in enacting and enforcing said policies. After examining the aforementioned variables, I will end my assessment by weighing the strengths and weaknesses of both the EU’s Strategic Vision and Reflection Paper while identifying preferences within the two narratives.

EU in an External Context: A SWOT Analysis

When it comes to examining the two perspectives presented, the documents must be viewed from their correlative timelines. The first document, “From Shared Vision to Common Action: Implementing the EU Global Strategy Year 1,” (I will refer to this as the Implementation paper) serves as a realist review of ongoing action within the EU’s three policy clusters in detailing the beginning stages of integrated approach and outlook towards the internal-external nexus along with an emphasized role of public diplomacy in the mix. On the other hand, the second document, “Reflection Paper on the Future of European Defense,” (I will refer to this as the Reflection paper) acts more so as a planning guide to define the potential frameworks for policies going forward into 2025. Once these documents are viewed within their respective timelines, a balanced “SWOT” analysis can assess the similarities and divergences of the options they present. Overwhelmingly, the theme of cooperation acts as a fundamental staple in both documents. In my opinion, this acts a force for unification and solidarity amongst member states from not only the point of view of common interest in all three policy areas, but also as a reminder of the benefits in the impact and cost of action as prescribed in the UN and NATO cases. Both documents seem to expand the EU’s context in terms of scope as embracing the means and demands for security in a global lens. The documents reinforce that in a globalized world, threats and their responses require an approach that extends beyond EU borders, and therefore a strong, coherent policy voice is needed to bring together member states and allies alike to defeat them.

Examining the divergences, much is left to be desired as far as the risks and opportunities are presented. In my perspective, I believe this was constructed purposefully as an attempt to leave the both areas as open as possible to allow for member states to interpret them in the context of their own narratives. In short, member state cohesion at literally every policy inroad proves to be the proverbial double-edged sword as the single largest risk and opportunity tasked by the organization. I think that the incessant rehashing of the need to stress state sovereignty at every turn while glamorizing the benefits of a single market and economies of scale identifies a bipolar divide in both documents that seems yet to be bridged by national sentiments even in the most agreeable of policy areas like diplomacy. The discord remains all but dependent on the tide of political discourse at the national level for years to come as the pace maker to materialize sufficient commitments in everything from budgets to bombs in order to achieve true policy success.

Who is the EU? Self-Perception and Potential Scenarios

After understanding the external context of the EU policy areas, we now turn to the element of self-perception and the roles of the EU as an international actor. Examining the relationship between the two stands as a crucial understanding of policy formulation as central to the core identity to the EU and vice versa. In this case, both documents provide key insight as to the position of the EU in a medium-term perspective. From the Implementation Paper, we see a humbled approach that pushes the EU to evolve from a regional, reactionary actor to a proactive, world power. The paper hones in on the legal roots and past successes of an integrated approach outside EU borders as a calling to solidify the Union’s mark as a vital organ for peace and defense. The paper then broadens such an identity to incorporate the elements of NATO and the UN cooperation as a segmenting role for member states contributions, such as intelligence collection and military technology/cyber warfare. In the Reflection Paper, I think the tone and phrasing speak more to the self-perceptions of individual citizens. The emotive language for the promotion of a just cause attitude stands reinforced by the onslaught of harmonizing buzzwords throughout the paper and the three scenarios such as “joint, collaborative, solidarity, shared, common, etc.”. In my perspective, such attempts draw in the need to reinforce, protect, and preserve a common identity both at home and abroad. This formation speaks to the development of both military and civilian capabilities as a means of securing and maintaining a strong EU position in the global order while supplementing the protection of what is near and dear at home.

Policy Today: Interests, Goals, and Values

When developing a coherent line of key interests, goals, and values across three focal policy structures, the EU makes strategic use of public perception as a litmus test to guide policy narratives. In the Reflection Paper, indications clearly point to a heightened citizen concern over immigration and terrorism from 2014-2016 taking clear priority over economic issues as the continent recovers. Such a reshuffling may pave the way for once-apprehensive politicians to reexamine budgeting priorities. Such a mandate could very well be the calling national governments need to allocate more of their defense spending to the EU while also ramping up domestic civilian and military infrastructure to contribute to common policy goals. Extending this notion of interest-based contributions over to the goals themselves, I think that member states are slowly developing the political will to see that a single market for defense ultimately becomes more attractive to the individual tax payer when all play a part. As the Reflection Paper explains, this can be translated as free/common market values with the development of economies of scale, boosted production, and increased competition. In each of the three scenarios outlined, the values act as matched components to these goals and interests. Therefore, readers retain a guiding set of “principles” as the basis for the plan’s “actions” and “capabilities.” The alignment of interests, goals, and values remains a difficult but necessary target in all policy areas, as the final results have significant influence over the perception of publics that indirectly vote the policies into place. In my perspective, a lack of coherence between the three and the policies could be a potential pitfall for policy objectives as lost faith by the public may sink the voter appetite for future defense spending and action.

Making it Happen: Resources and Strategies

As the balance between the EU’s ways and means become a focal point for any CFSDP discussion, I wanted to enhance the focus between the resources and strategies to examine the distribution between EU and member state competencies. When it comes to resources in all three policy areas, individual member states’ own infrastructures become front and center. Even in the “collaborative” lens of a 21st century EU, foreign affairs, defense, and security mainly revolve as apparatuses of a state. Therefore, in order to achieve a common strategy, policy must make a concerted effort to maximize collective utilization of state assets while respecting state sovereignty. In the Reflection paper, an attempt to consolidate the two by bolstering the EU’s own defense budget acts as a middle ground. In this regard, I think the biggest opportunity for the EU to retain its own resources remains in technology. States are simply more eager to share their military tech than they are their own boots on the ground. Similarly, technology and its benefits are more easily transferrable between member states and the EU. Just as well, selling the idea of technology research to taxpayers that may one day see the fruits of such labor in civilian applications is an easier pill to swallow for politicians than having to justify the use of a state’s limited and precious human military capital for an EU assignment not all may agree with. A type of “technological independence” the third scenario implies would optimally direct funding in a manner that balances state military capacity where it acts best while joining the common strategy for EU technological superiority that all member states can equally benefit from.

Narratives and Norms: A Final Comparison

After reviewing the progress made in the Implementation Paper and balancing it with the goals set forth in the Reflection paper, it remains clear that serious decisions towards the future of EU CFSDP still need to be made. The EU Global Strategy treads lightly on the most important topics for voters like immigration and terrorism that remain works in progress under the program’s steps for “resilience” and the beginnings of an integrated approach. That being said, my perspective in this program lens remains that the role and funding of public diplomacy unfortunately remains undercut by the giant umbrella of security and defense. To delve into the assessment of counterterrorism policy as a solely defensive measure does a disservice to the massive, existing network of EU diplomatic missions serving abroad that effectively act as proactive anti-terrorism measures in themselves. At the same time, supplementing funding to public diplomacy programs would take some of the pressure off member states to release their military capabilities for joint use. In this facet, I empathize with the member state politician and voter in their apprehensiveness to serve as the use of force in even the most justifiable situations. A refocus on funding in the diplomacy side is a cost effective alternative and investment that member states can make to reduce the likelihood that their troops will need to serve abroad on behalf of the EU. The success of diplomacy can be seen in areas like immigration, where the Partnership Framework on Migration has attempted to work with countries of origin to stabilize governments and assist civilians.

Turning the page to the Reflection Paper, I think much is left to be desired in terms of the development of the three scenarios. Once again, the scenario parameters are purposefully vague to effectively sell the plan to a wide variety of narratives. At the same time, I found it reprehensible that despite the massive rhetoric to budgetary concerns, none of the three scenarios incorporated any type of estimate fiscal dimension to compare and contrast the visions. Obviously, the contributions of member states will vary widely but I think that a concerted campaign to incentivize a transparent contribution table in terms financing, military assets, diplomatic assets, or (ideally) a combination of the three would see a more realpolitik approach to what the EU does and does not possess in the capacity to achieve in these policy areas. Ultimately, I believe that Scenario C “Common Defense and Security” retains the most to offer member states while effectively balancing the contributions and competencies equally. I think that the scenario utilizes the commitments to NATO and reinforces the importance of technological independence. As such, the importance of a well-defined plan to develop and maintain cutting-edge technology in all three policy areas cannot be overstated and, in my opinion, will become not only the most common battlefield, but also the critical one as the world enters into a 21st century of cyber warfare.

WORKS CITED

European Union. (2016). From Shared Vision to Common Action: The EU’s Global Strategic Vision: Year 1.

European Union. (2016). Reflection Paper on the Future of European Defense.

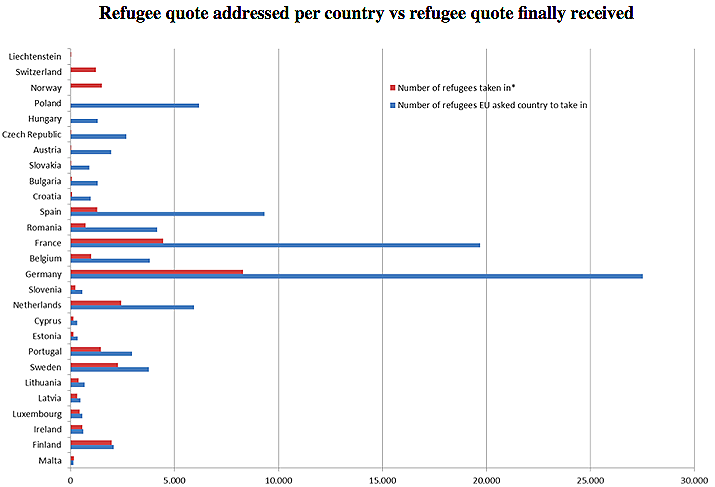

ENSAYO / Lucía Serrano Royo

En la actualidad unos 60 millones de personas se encuentran forzosamente desplazadas en el mundo (Arenas-Hidalgo, 2017).[1] Las cifras adquieren mayor trascendencia si se observa que más del 80% de los flujos migratorios se dirigen a países en vías de desarrollo, mientras que solo un 20% tienen como meta los países desarrollados, que a su vez poseen más medios y riqueza, y serían más aptos para acoger estos flujos migratorios.

En 2015 Europa acogió a 1,2 millones de personas, lo que supuso una magnitud sin precedentes desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Esta situación ha dado lugar a un intenso debate sobre solidaridad y responsabilidad entre los Estados miembros.

La forma en la que se ha legislado esta materia en la Unión Europea ha dado lugar a irregularidades en su aplicación entre los diferentes Estados. Esta materia dentro del sistema de la Unión Europea se trata de una competencia compartida del espacio de libertad, seguridad y justicia. El Tratado Funcionamiento de la Unión Europea (TFUE) en su artículo 2.2 y 3 se establecen que en estas competencias, son los Estados los que deben legislar en la medida en que la Unión no ejerce su competencia. Esto ha dado lugar a un desarrollo de forma parcial y desigualdades.

Desarrollo legislativo

La figura de los refugiados se recoge por primera vez en un documento internacional en la Convención sobre el Estatuto de Refugiados de Ginebra (1951) y su Protocolo de 1967. (ACNUR: La Agencia de la ONU para los Refugiados, 2017)[2]. A pesar de este gran avance, el tratamiento de los refugiados era diferente en cada Estado miembro, al tratarse su política nacional. Por ello, en un intento de armonizar las políticas nacionales, se firmó en 1990 el Convenio de Dublín. A pesar de ello, no fue hasta el Tratado de Ámsterdam en mayo de 1999, cuando se estableció como objetivo crear un espacio de libertad, seguridad y justicia, tratando la materia de inmigración y asilo como una competencia compartida. Ya en octubre de 1999, el Consejo Europeo celebró una sesión especial para la creación de un espacio de libertad, seguridad y justicia en la Unión Europea, concluyendo con la necesidad de crear un Sistema Europeo Común de Asilo (SECA) (CIDOB, 2017)[3]. Finalmente, estas políticas en materia de asilo se convierten en materia común con el Tratado de Lisboa y su desarrollo en el TFUE.

Actualmente, su razón de ser está recogida en el art 67 y siguientes del TFUE, donde se establece que la Unión constituye un espacio de libertad, seguridad y justicia dentro del respeto de los derechos fundamentales y de los distintos sistemas y tradiciones jurídicos de los Estados miembros. Este espacio también garantizará la ausencia de controles de las personas en las fronteras interiores. Además, se establece que la UE se desarrollará una política común de asilo, inmigración y control de las fronteras exteriores (art 67.2 TFUE) basada en la solidaridad entre Estados miembros, que sea equitativa respecto de los nacionales de terceros países. Pero el espacio de libertad, seguridad y justicia no es un compartimento estanco en los tratados, sino que tiene que interpretarse a la luz de otros apartados.

Esta competencia se debe analizar, por un lado, bajo el marco de libre circulación de personas dentro de la Unión Europea, y por otro, teniendo en cuenta el ámbito financiero. En cuanto a la libertad de circulación de personas, se debe aplicar el artículo 77 TFUE, que insta a la Unión a desarrollar una política que garantice la ausencia total de controles de las personas en las fronteras interiores, garantizando a su vez el control en las fronteras exteriores. Para ello, el Parlamento Europeo y el Consejo, con arreglo al procedimiento legislativo ordinario, deben establecer una política común de visados y otros permisos de residencia de corta duración, controles y condiciones en las que los nacionales de terceros países podrán circular libremente por la Unión. En cuanto al ámbito financiero, se debe tener en cuenta el artículo 80 TFUE, que establece el principio de solidaridad en las políticas de asilo, inmigración y control, atendiendo al reparto equitativo de la responsabilidad entre los Estados miembros.

Además, un aspecto fundamental para el desarrollo de esta materia ha sido la armonización del término refugiado por la Unión, definiéndolo como nacionales de terceros países o apátridas que se encuentren fuera de su país de origen y no quieran o no puedan volver a él debido al temor fundado a ser perseguidos en razón de su raza, religión, nacionalidad u opinión (Eur-ex.europa.eu, 2017)[4] . Esto es de especial importancia porque estas son las características necesarias para adquirir la condición de refugiado, que a su vez es necesario para obtener el asilo en la Unión Europea.

Situación en Europa

A pesar del desarrollo legislativo, la respuesta en Europa a la crisis humanitaria tras el estallido del conflicto en Siria, junto con el recrudecimiento de aquellos que se suceden en Iraq, Afganistán, Eritrea o Somalia, ha sido muy poco eficaz, lo que ha hecho tambalear el sistema.

La decisión de conceder o retirar el estatuto de refugiado pertenece a cada autoridad interna de los Estados, y por tanto puede diferir de un Estado a otro. Lo que hace la Unión Europea es garantizar una protección común y garantizar que los solicitantes de asilo tengan acceso a procedimientos de asilo justos y eficaces. Por ello la UE trata de establecer un sistema coherente para la toma de decisiones al respecto por parte de los Estados miembros, desarrollando normas sobre el proceso completo de solicitud de asilo. Además, en el caso en el que la persona no cumpla los requisitos para ser refugiado, pero se encuentre en una situación delicada por riesgo a sufrir daños graves en caso de retorno a su país, tiene derecho a una protección subsidiaria. A estas personas se les aplica el principio de no devolución, es decir, tienen derecho ante todo a no ser conducidas a un país donde haya riesgo para sus vidas.

El problema de este sistema es que solamente Turquía y Líbano acogen 10 veces más refugiados que toda Europa, que hasta 2016 sólo tramitó 813.599 solicitudes de asilo. Concretamente España concedió protección a 6.855 solicitantes, de los cuales 6.215 eran sirios[5]; pese al incremento respecto a años anteriores, las cifras seguían siendo las más bajas en el entorno europeo.

Muchas de las personas que desembarcan en Grecia o Italia, emprenden de nuevo su rumbo hacia los Balcanes a través de Yugoslavia y Serbia hasta Hungría, ante las deficiencias de gestión y las condiciones precarias que encontraron en estos países de acogida.

Para intentar aplicar el principio de solidaridad y cooperación, se estableció en 2015 una serie de cuotas para aliviar la crisis humanitaria y la presión establecida en Grecia e Italia. Los Estados miembros debían repartirse 120.000 asilados, y todos los países debían acatarlo. El principal interesado fue Alemania. Otro de los mecanismos que se creó fue un fondo con cargo al Mecanismo para los Refugiados en Turquía, para satisfacer las necesidades de los refugiados acogidos en ese país. La Comisión destinó un importe total de 2.200 millones de euros, y presupuestó 3.000 millones en 2016-2017[6].

Ante esta situación los países han reaccionado de manera diferente dentro de la Unión. Frente a países como Alemania, que buscan una forma de combatir el envejecimiento y la reducción de la población en su Estado mediante la entrada de refugiados, otros Estados miembros son reacios a la aplicación de las políticas. Incluso en algunos países de la Unión Europea, los partidos nacionalistas ganan fuerza y apoyos: en Holanda, Geert Wilders (Partido de la Libertad); en Francia, Marine Le Pen (Frente Nacional), y en Alemania, Frauke Petry (partido Alternativa para Alemania). A pesar de que esos partidos no son la principal fuerza política en esos países, esto refleja el descontento de parte de población ante la entrada de refugiados en los Estados. También es destacable el caso de Reino Unido, puesto que una de las causas del Brexit fue el deseo de recuperar el control sobre la entrada de los inmigrantes en el país. Además, en un primer momento Reino Unido ya se descolgó del sistema de cuotas aplicado en el resto de Estados miembros. Como se confirma en sus negociaciones, la premier Teresa May prioriza el rechazo a la inmigración por encima del libre comercio en la UE.

Mecanismos específicos para el desarrollo del ESLJ

Las fronteras entre los distintos países de la Unión se han difuminado. Con el código de fronteras Schengen y el código comunitario sobre visados se han abierto las fronteras, integrándose y permitiendo así la libre circulación de personas. Para el funcionamiento de estos sistemas ha sido necesario el establecimiento de normas comunes sobre la entrada de personas y el control de los visados, puesto que una vez pasada la frontera exterior de la UE los controles son mínimos. Por ello, las comprobaciones de documentación varían dependiendo de los lugares de origen de los destinatarios, teniendo un control más detallado para aquellos ciudadanos que no son de la Unión. Solo excepcionalmente se ha previsto el restablecimiento del control en las fronteras interiores (durante un periodo máximo de treinta días), en caso de amenaza grave para el orden público y la seguridad interior.

Puesto que el control de las fronteras exteriores depende de los Estados donde se encuentren, se han creado sistemas como Frontex 2004, a partir de los Centros ad hoc de Control Fronterizo establecidos en 1999, que proporciona ayuda a los Estados en el control de las fronteras exteriores de la UE, principalmente a aquellos países que sufren grandes presiones migratorias (Frontex.europa.eu, 2017) [7]. También se ha creado el Fondo de Seguridad Interior, un sistema de apoyo financiero surgido en 2014 y destinado a reforzar las fronteras exteriores y los visados.

Otro mecanismo activo es el Sistema Europeo Común de Asilo (SECA), para reforzar la cooperación de los países de la UE, donde teóricamente los Estados miembros deben asignar 20% de los recursos disponibles[8]. Para su aplicación, se estableció el Fondo de Asilo, Migración e Integración (FAMI) (2014-2020) necesario para promover la eficacia de la gestión de los flujos migratorios. Además, en el SECA se ha establecido una política de asilo para la Unión Europea, que incluye una directiva sobre procedimientos de asilo y una directiva sobre condiciones de acogida. En este sistema se integra el Reglamento Dublín, de acuerdo con las Convención de Ginebra. Es un mecanismo fundamental y aunque este sistema se ha simplificado, unificado y aclarado, ha causado más controversias en materia de refugiados. Se estableció para racionalizar los procesos de solicitudes de asilo en los 32 países que aplican el Reglamento. Con arreglo a esta ley, solo un país es responsable del examen de su solicitud: el país que toma las huellas del refugiado, es decir, al primero que llegó y pidió protección internacional. Esto funciona independientemente de que la persona viaje o pida asilo en otro país; el país competente es aquel en el que se tomaron primero las huellas al refugiado. Este sistema se apoya en el EURODAC, puesto que es un sistema central que ayuda a los Estados miembros de la UE a determinar el país responsable de examinar una solicitud de asilo, comparando las impresiones dactilares.

El Consejo Europeo de Refugiados y Exiliados ha remarcado los dos problemas principales de este sistema: por un lado, lleva a los refugiados a viajar de forma clandestina y peligrosa hasta llegar a su país de destino, para evitar que les tome las huellas otro país distinto de aquel en el que se quieren asentar. Por otro lado, Grecia e Italia, que son los principales destinos de las corrientes de inmigrantes, no pueden con la carga que este sistema les impone para procesar las masas de personas que llegan a su territorio en busca de protección.

Casos ante el Tribunal de Justicia de la UE

El Tribunal de Justicia de la Unión Europea se ha pronunciado en varios aspectos relativos a la actuación ante la inmigración y el tratamiento de los refugiados por parte los Estados miembros. En algunas ocasiones el tribunal se ha mantenido férreo en la aplicación de la normativa homogénea de la Unión, mientras que en otros casos el tribunal ha dejado la cuestión a la discrecionalidad de los diferentes Estados miembros.

El tribunal falló en favor de una actuación común en el caso un nacional de un tercer país (Sr. El Dridi) que entró ilegalmente en Italia sin permiso de residencia. El 8 de mayo de 2004 el Prefecto de Turín dictó contra él un decreto de expulsión. El TJUE (STJUE, 28 abril 2011)[9] falló que a pesar de que un inmigrante se encuentre en situación ilegal y permanezca en el territorio del referido Estado miembro sin causa justificada, incluso con la concurrencia de una infracción de una orden de salida de dicho territorio en un plazo determinado, el Estado no puede imponer pena de prisión, puesto que siguiendo la Directiva 2008/115, excluyen la competencia penal de los Estados miembros en el ámbito de la inmigración clandestina y de la situación irregular. De este modo, los Estados deben ajustar su legislación para asegurar el respeto del Derecho de la Unión.

Por otro lado, el tribunal deja en manos de los Estados la decisión de enviar de vuelta a un tercer país a un inmigrante que haya solicitado protección internacional en su territorio, si considera que ese país responde a los criterios de «país tercero seguro». Incluso el tribunal falló (STJUE, 10 de diciembre de 2013) [10]que, con objeto de racionalizar la tramitación de las solicitudes de asilo y de evitar la obstrucción del sistema, el Estado miembro mantiene su prerrogativa en el ejercicio del derecho a conceder asilo con independencia de cuál sea el Estado miembro responsable del examen de una solicitud. Esta facultad deja un gran margen de apreciación a los Estados. La homogeneidad en este caso solo se aprecia en el caso de que haya deficiencias sistemáticas del procedimiento de asilo y de las condiciones de acogida de los solicitantes de asilo en ese Estado, o bien tratos degradantes.

Por una actitud más activa

La Unión Europea ha establecido multitud de mecanismos, y tiene competencia para ponerlos en marcha, pero su pasividad y la actitud reacia de los Estados miembros a la hora de acoger a los refugiados ponen en duda la unidad del sistema de la Unión Europea y la libertad de movimiento que caracteriza a la propia UE. La situación a la que se enfrenta es compleja, puesto que hay una crisis humanitaria derivada del flujo de inmigrantes necesitados de ayuda en sus fronteras. Mientras tanto, los Estados se muestran pasivos e incluso contrarios a la mejora del sistema, hasta el punto que algunos Estados han propuesto la restauración de los controles de fronteras interiores (El Español, 2017).[11] Esta situación ha sido provocada principalmente por una falta de control efectivo sobre sus fronteras dentro de la Unión, y por otro lado por una sociedad que muestra recelo ante la apertura de las fronteras por la inseguridad.

La crisis de los refugiados es un problema real y cerrar las fronteras no hará desaparecer el problema. Por ello, los países europeos deberían adoptar una perspectiva común y activa. El destino de fondos sirve de ayuda en esta crisis humanitaria, pero no es la única solución. Uno de los principales problemas sin resolver es la situación de las personas en campos de refugiados, las cuales se encuentran en condiciones precarias y deberían ser acogidos de forma digna. La Unión debería reaccionar más activamente ante estas situaciones, haciendo uso de su competencia en materia de asilo y llegada de inmigración con afluencia masiva, recogido en el art 78 TFUE c).

Esta situación sigue siendo uno de los objetivos principales para la agenda de la Unión Europea ya que en el Libro Blanco se establece el refuerzo de la Agenda de Migración, actuaciones sobre la crisis de los refugiados y aspectos sobre la crisis de población de Europa. Se aboga por un incremento de las políticas de inmigración y protección de la inmigración legal, combatiendo a su vez la inmigración ilegal, ayudando tanto a los inmigrantes como a la población europea (Comisión europea, 2014) [12]. A pesar de estos planes y perspectivas positivas, se ha de tener en cuenta la delicada situación ante la que internamente se encuentra la UE, con casos como la retirada de un Estado con poder dentro de la Unión (el Brexit), lo que podría dar lugar a un desvío en los esfuerzos de las políticas comunitarias, dejando de lado temas cruciales, como lo es la situación de los refugiados.

[1] Arenas-Hidalgo, N. (2017). Flujos masivos de población y seguridad. La crisis de personas refugiadas en el Mediterráneo. [online] Redalyc.org. [Accessed 9 Jul. 2017]

[2] ACNUR: La Agencia de la ONU para los Refugiados. (2017). ¿Quién es un Refugiado? [online] [Accessed 10 Jul. 2017]

[3] CIDOB. (2017). CIDOB - La política de refugiados en la Unión Europea. [online] [Accessed 10 Jul. 2017].

[4] Eur-lex.europa.eu. (2017). EUR-Lex - l33176 - EN - EUR-Lex. [online] Available [Accessed 10 Jul. 2017].

[5] Datos del CEAR (Comison Española de Ayuda al Refugiado) de Marzo de 2017 Anon, (2017). [online] [Accessed 10 May 2017].

[6] Anon, (2017). [online] [Accessed 11 Jul. 2017].

[7] Frontex.europa.eu. (2017). Frontex | Origin. [online] [Accessed 12 Jul. 2017].

[8] https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/e-library/docs/ceas-fact-sheets/ceas_factsheet_es.pdf [Accessed 12 Jul. 2017].

[9] Tribunal de Justicia de la Unión Europea [online]. ECLI:EU:C:2011:268, del 28 abril 2011 [consultado 10 junio 2017]

[10] Tribunal de Justicia de la Unión Europea [online].ECLI:EU:C:2013:813, del10 de diciembre de 2013 [consultado 10 junio 2017]

[11] El Español. (2017). Los controles en las fronteras europeas pueden dilapidar un tercio del crecimiento. [online] [Accessed 11 Jul. 2017].

[12] Comisión Europea (2014). Migracion y asilo.

WORKING PAPER / N. Moreno, A. Puigrefagut, I. Yárnoz

ABSTRACT

The fundamental characteristic of the external action of the European Union (EU) in recent years has been the use of the so-called soft power. This soft power has made the Union a key actor for the development of a large part of the world’s regions. The last decades the EU has participated in a considerable amount of projects in the economic, cultural and political fields in order to fulfil the article 2 of its founding Treaty and thus promote their values and interests and contribute to peace, security and sustainable development of the globe through solidarity and respect for all peoples. Nevertheless, EU’s interventions in different regions of the world have not been free of objections that have placed in the spotlight a possible direct attack by the Union to the external States’ national sovereignties, thus creating a principle of neo-colonialism by the EU.

Download the document [pdf. 548K]

Download the document [pdf. 548K]

DOC. DE TRABAJO / A. Palacios, M. Lamela, M. Biera [Versión en inglés]

RESUMEN

La Unión Europea (UE) se ha visto especialmente dañada internamente por campañas de desinformación que han cuestionado su legislación y sus mismos valores. Las distintas operaciones desinformativas y la incapacidad comunicativa de las instituciones de la Unión Europea han generado un sentimiento de alarma en Bruselas. Apenas un año antes de la celebración de las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo, Europa ha concentrado muchos de sus esfuerzos en hacer frente al desafío desinformativo, generando nuevas estrategias y grupos de trabajo como el Stratcom Task Force o el grupo de expertos de la Comisión Europea.

Descargar el documento completo [pdf. 381K]

Descargar el documento completo [pdf. 381K]

ESSAY / Elena López-Dóriga

The European Union’s aim is to promote democracy, unity, integration and cooperation between its members. However, in the last years it is not only dealing with economic crises in many countries, but also with a humanitarian one, due to the exponential number of migrants who run away from war or poverty situations.

When referring to the humanitarian crises the EU had to go through (and still has to) it is about the refugee migration coming mainly from Syria. Since 2011, the civil war in Syria killed more than 470,000 people, mostly civilians. Millions of people were displaced, and nearly five million Syrians fled, creating the biggest refugee crisis since the World War II. When the European Union leaders accorded in assembly to establish quotas to distribute the refugees that had arrived in Europe, many responses were manifested in respect. On the one hand, some Central and Eastern countries rejected the proposal, putting in evidence the philosophy of agreement and cooperation of the EU claiming the quotas were not fair. Dissatisfaction was also felt in Western Europe too with the United Kingdom’s shock Brexit vote from the EU and Austria’s near election of a far right-wing leader attributed in part to the convulsions that the migrant crisis stirred. On the other hand, several countries promised they were going to accept a certain number of refugees and turned out taking even less than half of what they promised. In this note it is going to be exposed the issue that occurred and the current situation, due to what happened threatened many aspects that revive tensions in the European Union nowadays.

The response of the EU leaders to the crisis

The greatest burden of receiving Syria’s refugees fell on Syria’s neighbors: Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. In 2015 the number of refugees raised up and their destination changed to Europe. The refugee camps in the neighbour countries were full, the conditions were not good at all and the conflict was not coming to an end as the refugees expected. Therefore, refugees decided to emigrate to countries such as Germany, Austria or Norway looking for a better life. It was not until refugees appeared in the streets of Europe that European leaders realised that they could no longer ignore the problem. Furthermore, flows of migrants and asylum seekers were used by terrorist organisations such as ISIS to infiltrate terrorists to European countries. Facing this humanitarian crisis, European Union ministers approved a plan on September 2015 to share the burden of relocating up to 120,000 people from the so called “Frontline States” of Greece, Italy and Hungary to elsewhere within the EU. The plan assigned each member state quotas: a number of people to receive based on its economic strength, population and unemployment. Nevertheless, the quotas were rejected by a group of Central European countries also known as the Visegrad Group, that share many interests and try to reach common agreements.

Why the Visegrad Group rejected the quotas

The Visegrad Group (also known as the Visegrad Four or simply V4) reflects the efforts of the countries of the Central European region to work together in many fields of common interest within the all-European integration. The Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia have shared cultural background, intellectual values and common roots in diverse religious traditions, which they wish to preserve and strengthen. After the disintegration of the Eastern Block, all the V4 countries aspired to become members of the European Union. They perceived their integration in the EU as another step forward in the process of overcoming artificial dividing lines in Europe through mutual support. Although they negotiated their accession separately, they all reached this aim in 2004 (1st May) when they became members of the EU.

The tensions between the Visegrad Group and the EU started in 2015, when the EU approved the quotas of relocation of the refugees only after the dissenting votes of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia were overruled. In asking the court to annul the deal, Hungary and Slovakia argued at the Court of Justice that there were procedural mistakes, and that quotas were not a suitable response to the crisis. Besides, the politic leaders said the problem was not their making, and the policy exposed them to a risk of Islamist terrorism that represented a threat to their homogenous societies. Their case was supported by Polish right-wing government of the party Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice) which came to power in 2015 and claimed that the quotes were not comprehensive.

Regarding Poland’s rejection to the quotas, it should be taken into account that is a country of 38 million people and already home to an exponential number of Ukrainian immigrants. Most of them decided to emigrate after military conflict erupted in eastern Ukraine in 2014, when the currency value of the Ukrainian hryvnia plummeted and prices rose. This could be a reason why after having received all these immigration from Ukraine, the Polish government believed that they were not ready to take any more refugees, and in that case from a different culture. They also claimed that the relocation methods would only attract more waves of immigration to Europe.

The Slovak and Hungarian representatives at the EU court stressed that they found the Council of the EU’s decision rather political, as it was not achieved unanimously, but only by a qualified majority. The Slovak delegation labelled this decision “inadequate and inefficient”. Both the Slovak and Hungarian delegations pointed to the fact that the target the EU followed by asserting national quotas failed to address the core of the refugee crisis and could have been achieved in a different way, for example by better protecting the EU’s external border or with a more efficient return policy in case of migrants who fail to meet the criteria for being granted asylum.

The Czech prime minister at that time, Bohuslav Sobotka, claimed the commission was “blindly insisting on pushing ahead with dysfunctional quotas which decreased citizens’ trust in EU abilities and pushed back working and conceptual solutions to the migration crisis”.

Moreover, there are other reasons that run deeper about why ‘new Europe’ (these recently integrated countries in the EU) resisted the quotas which should be taken into consideration. On the one hand, their just recovered sovereignty makes them especially resistant to delegating power. On the other, their years behind the iron curtain left them outside the cultural shifts taking place elsewhere in Europe, and with a legacy of social conservatism. Furthermore, one can observe a rise in skeptical attitudes towards immigration, as public opinion polls have shown.

|

* As of September 2017. Own work based on this article |

The temporary solution: The Turkey Deal

The accomplishment of the quotas was to be expired in 2017, but because of those countries that rejected the quotas and the slow process of introducing the refugees in those countries that had accepted them, the EU reached a new and polemic solution, known as the Turkey Deal.

Turkey is a country that has had the aspiration of becoming a European Union member since many years, mainly to improve their democracy and to have better connections and relations with Western Europe. The EU needed a quick solution to the refugee crisis to limit the mass influx of irregular migrants entering in, so knowing that Turkey is Syria’s neighbor country (where most refugees came from) and somehow could take even more refugees, the EU and Turkey made a deal the 18th of March 2016. Following the signing of the EU-Turkey deal: those arriving in the Greek Islands would be returned to Turkey, and for each Syrian sent back from Greece to Turkey one Syrian could be sent from a Turkish camp to the EU. In exchange, the EU paid 3 billion euros to Turkey for the maintenance of the refugees, eased the EU visa restrictions for Turkish citizens and payed great lip-service to the idea of Turkey becoming a member state.

The Turkey Deal is another issue that should be analysed separately, since it has not been defended by many organisations which have labelled the deal as shameless. Instead, the current relationship between both sides, the UE and V4 is going to be analysed, as well as possible new solutions.

Current relationship between the UE and V4

In terms of actual relations, on the one hand critics of the Central European countries’ stance over refugees claim that they are willing to accept the economic benefits of the EU, including access to the single market, but have shown a disregard for the humanitarian and political responsibilities. On the other hand, the Visegrad Four complains that Western European countries treat them like second-class members, meddling in domestic issues by Brussels and attempting to impose EU-wide solutions against their will, as typified by migrant quotas. One Visegrad minister told the Financial Times, “We don’t like it when the policy is defined elsewhere and then we are told to implement it.” From their point of view, Europe has lost its global role and has become a regional player. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban said “the EU is unable to protect its own citizens, to protect its external borders and to keep the community together, as Britain has just left”.

Mr Avramopolus, who is Greece’s European commissioner, claimed that if no action was taken by them, the Commission would not hesitate to make use of its powers under the treaties and to open infringement procedures.

At this time, no official sanctions have been imposed to these countries yet. Despite of the threats from the EU for not taking them, Mariusz Blaszczak, Poland´s former Interior minister, claimed that accepting migrants would have certainly been worse for the country for security reasons than facing EU action. Moreover, the new Poland’s Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki proposes to implement programs of aid addressed to Lebanese and Jordanian entities on site, in view of the fact that Lebanon and Jordan had admitted a huge number of Syrian refugees, and to undertake further initiatives aimed at helping the refugees affected by war hostilities.

To sum up, facing this refugee crisis a fracture in the European Union between Western and Eastern members has showed up. Since the European Union has been expanding its boarders from west to east integrating new countries as member states, it should also take into account that this new member countries have had a different past (in the case of the Eastern countries, they were under the iron curtain) and nowadays, despite of the wish to collaborate all together, the different ideologies and the different priorities of each country make it difficult when it comes to reach an agreement. Therefore, while old Europe expects new Europe to accept its responsibilities, along with the financial and security benefits of the EU, this is going to take time. As a matter of fact, it is understandable that the EU Commission wants to sanction the countries that rejected the quotas, but the majority of the countries that did accept to relocate the refugees in the end have not even accepted half of what they promised, and apparently they find themselves under no threats of sanction. Moreover, the latest news coming from Austria since December 2017 claim that the country has bluntly told the EU that it does not want to accept any more refugees, arguing that it has already taken in enough. Therefore, it joins the Visegrad Four countries to refuse the entrance of more refugees.

In conclusion, the future of Europe and a solution to this problem is not known yet, but what is clear is that there is a breach between the Western and Central-Eastern countries of the EU, so an efficient and fair solution which is implemented in common agreement will expect a long time to come yet.

Bibliography:

J. Juncker. (2015). A call for Collective Courage. 2018, de European Commission Sitio web.

EC. (2018). Asylum statistics. 2018, de European Commission Sitio web.

International Visegrad Fund. (2006). Official Statements and communiqués. 2018, de Visegrad Group Sitio web.

Jacopo Barigazzi (2017). Brussels takes on Visegrad Group over refugees. 2018, de POLITICO Sitio web.

Zuzana Stevulova (2017). “Visegrad Four” and refugees. 2018, de Confrontations Europe (European Think Tank) Sitio web.

Nicole Gnesotto. (2015). Refugees are an internal manifestation of an unresolved external crisis. 2018, de Confrontations Europe (European Think Tank) Sitio web.

ENSAYO / Túlio Dias de Assis [Versión en inglés]

El presidente de Estados Unidos, Donald Trump, sorprendió en diciembre con otra de sus declaraciones, que al igual que muchas anteriores tampoco carecía de polémica. Esta vez el tema sorpresa fue el anuncio de la apertura de la embajada de EEUU en Jerusalén, consumando así el reconocimiento de la milenaria urbe como capital del único estado judío del mundo actual: Israel.

El polémico anuncio de Trump, en un asunto tan controvertido como delicado, fue criticado internacionalmente y tuvo escaso apoyo exterior. No obstante, algunos países –pocos– se sumaron a la iniciativa estadounidense, y algunos más se manifestaron con ambigüedad. Entre estos, diversos medios situaron a varios países de la Unión Europea. ¿Ha habido realmente falta de cohesión interna en la Unión sobre esta cuestión?

Por qué Jerusalén importa

Antes de todo, cabría analizar con más detalle la situación, empezando por una pregunta sencilla: ¿Por qué Jerusalén es tan importante? Hay varios factores que llevan a que Hierosolyma, Yerushalayim, Al-quds o simplemente Jerusalén tenga tamaña importancia no solo a nivel regional, sino también globalmente, entre los cuales destacan los siguientes tres: su relevancia histórica, su importancia religiosa y su valor geoestratégico.

Relevancia histórica. Es uno de los asentamientos humanos más antiguos del mundo, remontándose sus primeros orígenes al IV milenio a.C. Aparte de ser la capital histórica tanto de la región de Palestina o Canaán, como de los varios reinos judíos establecidos a lo largo del primer milenio a.C. en dicha parte del Levante.

Importancia religiosa. Se trata de una ciudad sacratísima para las tres mayores religiones monoteístas del mundo, cada una por sus propias razones: para el Cristianismo, principalmente debido a que es donde se produjo la crucificción de Cristo; para el Islamismo, aparte de ser la ciudad de varios profetas –compartidos en las creencias de las demás religiones abrahámicas– y un lugar de peregrinación, también es adonde hizo Mahoma su tan conocido viaje nocturno; y obviamente, para el Judaísmo, por razones históricas y además por ser donde se construyó el tan sacro Templo de Salomón.

Valor geoestratégico. A nivel geoestratégico también posee una gran relevancia, ya que se trata de un punto crucial que conecta la costa mediterránea levantina con el valle del Jordán. Por lo que su poseedor tendría bajo su control una gran ventaja geoestratégica en la región del Levante.