Breadcrumb

Blogs

Entries with Categorías Global Affairs Artículos .

Narratives from the Kremlin, the Duma and nationalist media embellish Russia's history in an open culture warfare against the West

Russian media and politicians, influenced by a nationalist ideology, often use Russian history, particularly from the Soviet time, to create a national consciousness and praise themselves for their contributions to world affairs. This often results in manipulation and in a rising hostility between Russia and other countries, especially in Eastern Europe.

A colored version of the picture taken in Berlin by the Red Army photographer Yevgueni Jaldei days before the Nazi's capitulation

ARTICLE / José Javier Ramírez

Media bias. Russia is in theory a democracy, with the current president Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin having been elected through several general elections. His government, nonetheless, has been accused of restricting freedom of opinion. Russia is ranked 149 out of 179 countriesin the Press Freedom Index, so it is no surprise that main Russian media (Pravda, RT, Sputnik News, ITAR-TASS, …) are strong supporters of the government’s version of history. They have been emphasizing on Russia’s glorious military history, notoriously since 2015 when they tried to counter international rejection of the Russian invasion of Crimea appealing to the spirit of the 70th World War II anniversary. On the other side, social networks are not often used: Putin lacks a Twitter account, and the Kremlin accounts’ posts are not especially significant nor controversial.

Putin’s ideology, often called Putinism, involves a domination of the public sphere by former security and military staff, which has led to almost all media pursuing to justify all Russian external aggressions, and presenting Western countries, traditionally opposed to these policies, as hypocritical and Russophobic. Out of the remarkable exceptions to these pro-government public sphere, we might mention Moscow Today newspaper (whose ideology is rather independent, in no way an actual opposition), and the leader of the Communist faction, Gennady Andreyevich Zyuganov, who was labelled Putin several times as a dictator, without too much success among the electorate.

Early period. Russian media take pride in having an enormously long history, to the extent of having claimed that one of its cities, Derbent, played a key role in several civilizations for two thousand years. However, the first millennium of such a long history often goes unmentioned, due to the lack of sources, and even when the role of the Mongolian Golden Horde is often called into question, perhaps in order to avoid recognizing that there was a time where Russians were subjected to foreign domination. In fact, Yuri Petrov, director of RAS Russian History Institute, has refused to accept that the Mongolian conquest was a colonization, arguing that it was a process of mixing with the Slavic and Mongolian elites.

Such arguments do not prevent TASS, Russian state’s official media, from having recognized the battle of Kulikovo (1380) as the beginning of Russian state history, since this was the time where all Russian states came together to gain independence. Similarly, Communist leader Zyuganov stated that Russia is to be thanked for having protected Europe from the Golden Horde’s invasion. In other words, Russian media have a contradictory position about the nation’s beginning: on one hand, they deny having been conquered by the Mongolian, or prefer not to mention such a topic; on the other, they widely celebrate the defeat of the Golden Horde as a symbol of their freedom and power. Similar contradictions are quite common in such an official history, dominated by nationalist bias.

Czarism. Unlike what might be thought, Russian Czars are held in relative high esteem. Orthodox Church has canonized Nicolas II as a martyr for the “patience and resignation” with which he accepted his execution, while public polls carried by TASS argued that most Russians perceive his execution as barbaric and unnecessary. Pravda has even argued that there has been a manipulation of the last Czar’s story both by Communists and the West (mutual accusations of manipulation between Russian and Western media are quite common): according to Pyotr Multatuli, a historian interviewed by Pravda, the last Czar was someone with fatherly love towards its citizens, and he just happened to be betrayed by conspirators, who killed him to justify their legitimacy.

But this nostalgic remembrance is not exclusive solely to the last Czar, there are actually multiple complimentary references to several monarchs: Peter the Great was credited by Putin for introducing honesty and justice as the state agencies principles; Catherine the Great for being a pioneer in experimentation with vaccines, and she was even the first monarch to have been vaccinated; Alexander III created a peaceful and strong Russia… Pravda, one of the most pro-monarchy newspapers, has even argued that Czars were actually more responsible and answerable to society than the USA politicians, or that Napoleon’s invasion was not actually defeated by General Winter, but by Alexander I’s strategy. The appreciation for the former monarchy might be due to the disappointment with the Soviet era, or in some way promoted by Putin, who since the Crimean crisis inaugurated several statues to honor Princes and Czars, without recognizing their tyranny. This can be understood as a way of presenting himself as a national hero, whose decisions must be obeyed even if they are undemocratic.

USSR. The Soviet Union is the most quoted period in the Russian media, both due to their proximity, and because it is often compared to today’s government. Perceptions about this period are quite different and to some extent contradictory. Zyuganov, the Communist leader, praises the Soviet government, considering it even more democratic that Putin’s government, and has advocated for a re-Stalinisation of Russia. Nonetheless, that is not the vision shared neither by Putin nor by most media.

Generally speaking, Russian media do not support Communist national policy (President Putin himself once took it as “inappropriate” being called neo-Stalinist). There is a recognition of Soviet crimes while, at the same time, they are accepted as something that simply happened, and to what not too much attention should be drawn. Stalin particularly is the most controversial character and a case of “doublethink”: President Putin has attended some events to honor Stalin’s victims, while at the same time sponsored textbooks that label him as an effective leader. The result, shown in several polls, is that there is a growing indifference towards Stalin’s legacy.

However, the approach is quite different when we talk about the USSR foreign policy, which is considered completely positive. The media praise the Russian bravery in defeating Nazi Germany, and doing it almost alone, and for liberating Eastern Europe. This praise has even been shown in the present: Russian anti-Covid vaccine has been given the name of “Sputnik V”, subtly linking Soviet former military technology and advancement to the saving of today’s world (the name of the first artificial satellite was already used for the news website and broadcaster Sputnik News). Moreover, Putin himself wrote an essay on the World War II where he argued that all European countries had their piece of fault (even Poland, whose occupation he justifies as politically compulsory) and that criticism of Russia's attitude is just a strategy of Western propaganda to avoid accepting its own responsibilities for the war.

This last point is particularly important in Russian media, who constantly criticize Western for portraying Russia and the Soviet Union as villains. According to RT, for instance, Norway should be much more thankful to Russia for its help, or Germany for Russia’s promotion of its unification. The reason for this ingratitude is often pointed to the United States and its imperialism, because it has always feared Russia’s strength and independence, according to Sputnik, and has tried to destroy it by all means. The accusations to the US vary among the Russian media, from Pravda’s accusation of the 1917 Revolution having been sponsored by Wall Street to destabilize Russia, to RT’s complaint that the US took advantage of Boris Yeltsin’s pro-Western policies to impose severe economic measures that ruined Russian economy and the citizens’ well-being (Pravda is particularly virulent towards the West).

What the European neighbours think. As in most countries, politicians in Russia use their national history mostly to magnify the reputation of the nation among the domestic public opinion and among international audiences, frequently emphasizing more the positive aspects than the negative ones. What distinguishes Russian media is the influence the Government has on them, which results in a remarkable history manipulation. Such manipulation has arrived to create some sort of doublethink: some events that glorify Russia (Czars’ achievements, Communist military success, etc.) are frequently quoted and mentioned while, at the same time, the dark side of these same events (Czars’ tyranny, Stalin’s repression, etc.) is ignored or rejected.

Manipulated Russian history is often incompatible with (manipulated or not) Western history, which has led to mutual accusations of hypocrisy and fake news that have severely undermined the relations between Russia and its Western neighbours (particularly Poland, whom Russia insists to blame to some extent for the World War II and to demand gratitude for the liberation provided by Russia). If Russia wants to strengthen its relationships, it must stop idealizing its national history and try to compare it with the Western version, particularly in topics referring to Communism and the 20th century. Only this way might tensions be eased, and there will be a possibility of fostering cooperation.

A separated chapter on this historical reconciliation should be worked with Russia's neighbours in Eastern Europe. Most of them shifted from Nazi occupation to Communist states, and now they are still consolidating its democracies. Eastern Europe societies have mixed feelings of love and rejection towards Russia, what they don't buy any more is the story of the Red Army as a force of liberation.

Behind the tension between Qatar and its neighbors is the Qatari ambitious foreign policy and its refusal to obey

Recent diplomatic contacts between Qatar and Saudi Arabia have suggested the possibility of a breakthrough in the bitter dispute held by Qatar and its Arab neighbors in the Gulf since 2017. An agreement could be within reach in order to suspend the blockade imposed on Qatar by Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain (and Egypt), and clarify the relations the Qataris have with Iran. The resolution would help Qatar hosting the 2022 FIFA World Cup free of tensions. This article gives a brief context to understand why things are the way they are.

▲ Ahmad Bin Ali Stadium, one of the premises for the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar

ARTICLE / Isabelle León

The diplomatic crisis in Qatar is mainly a political conflict that has shown how far a country can go to retain leadership in the regional balance of power, as well as how a country can find alternatives to grow regardless of the blockade of neighbors and former trading partners. In 2017, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain broke diplomatic ties with Qatar and imposed a blockade on land, sea, and air.

When we refer to the Gulf, we are talking about six Arab states: Saudi Arabia, Oman, UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait. As neighbors, these countries founded the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in 1981 to strengthen their relation economically and politically since all have many similarities in terms of geographical features and resources like oil and gas, culture, and religion. In this alliance, Saudi Arabia always saw itself as the leader since it is the largest and most oil-rich Gulf country, and possesses Mecca and Medina, Islam’s holy sites. In this sense, dominance became almost unchallenged until 1995, when Qatar started pursuing a more independent foreign policy.

Tensions grew among neighbors as Iran and Qatar gradually started deepening their trading relations. Moreover, Qatar started supporting Islamist political groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood, considered by the UAE and Saudi Arabia as terrorist organizations. Indeed, Qatar acknowledges the support and assistance provided to these groups but denies helping terrorist cells linked to Al-Qaeda or other terrorist organizations such as the Islamic State or Hamas. Additionally, with the launch of the tv network Al Jazeera, Qatar gave these groups a means to broadcast their voices. Gradually the environment became tense as Saudi Arabia, leader of Sunni Islam, saw the Shia political groups as a threat to its leadership in the region.

Consequently, the Gulf countries, except for Oman and Kuwait, decided to implement a blockade on Qatar. As political conditioning, the countries imposed specific demands that Qatar had to meet to re-establish diplomatic relations. Among them there were the detachment of the diplomatic ties with Iran, the end of support for Islamist political groups, and the cessation of Al Jazeera's operations. Qatar refused to give in and affirmed that the demands were, in some way or another, a violation of the country's sovereignty.

A country that proves resilient

The resounding blockade merited the suspension of economic activities between Qatar and these countries. Most shocking was, however, the expulsion of the Qatari citizens who resided in the other GCC states. A year later, Qatar filed a complaint with the International Court of Justice on grounds of discrimination. The court ordered that the families that had been separated due to the expulsion of their relatives should be reunited; similarly, Qatari students who were studying in these countries should be permitted to continue their studies without any inconvenience. The UAE issued an injunction accusing Qatar of halting the website where citizens could apply for UAE visas as Qatar responded that it was a matter of national security. Between accusations and statements, tensions continued to rise and no real improvement was achieved.

At the beginning of the restrictions, Qatar was economically affected because 40% of the food supply came to the country through Saudi Arabia. The reduction in the oil prices was another factor that participated on the economic disadvantage that situation posed. Indeed, the market value of Qatar decreased by 10% in the first four weeks of the crisis. However, the country began to implement measures and shored up its banks, intensified trade with Turkey and Iran, and increased its domestic production. Furthermore, the costs of the materials necessary to build the new stadiums and infrastructure for the 2022 FIFA World Cup increased; however, Qatar started shipping materials through Oman to avoid restrictions of UAE and successfully coped with the status quo.

This notwithstanding, in 2019, the situation caused almost the rupture of the GCC, an alliance that ultimately has helped the Gulf countries strengthen economic ties with European Countries and China. The gradual collapse of this organization has caused even more division between the blocking countries and Qatar, a country that hosts the largest military US base in the Middle East, as well as one of Turkey, which gives it an upper hand in the region and many potential strategic alliances.

The new normal or the beginning of the end?

Currently, the situation is slowly opening-up. Although not much progress has been made through traditional or legal diplomatic means to resolve this conflict, sports diplomacy has played a role. The countries have not yet begun to commercialize or have allowed the mobility of citizens, however, the event of November 2019 is an indicator that perhaps it is time to relax the measures. In that month, Qatar was the host of the 24th Arabian Gulf Cup tournament in which the Gulf countries participated with their national soccer teams. Due to the blockade, UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain had boycotted the championship; however, after having received another invitation from the Arabian Gulf Cup Federation, the countries decided to participate and after three years of tensions, sent their teams to compete. The sporting event was emblematic and demonstrated how sport may overcome differences.

Moreover, recently Saudi Arabia has given declarations that the country is willing to engage in the process to lift-up the restrictions. This attitude toward the conflict means, in a way, improvement despite Riyadh still claims the need to address the security concerns that Qatar generates and calls for a commitment to the solution. As negotiations continue, there is a lot of skepticism between the parties that keep hindering the path toward the resolution.

Donald Trump’s administration recently reiterated its cooperation and involvement in the process to end Qatar's diplomatic crisis. Indeed, US National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien stated that the US hopes in the next two months there would be an air bridge that will allow the commercial mobilization of citizens. The current scenario might be optimistic, but still, everything has remained in statements as no real actions have been taken. This participation is within the US strategic interest because the end of this rift can signify a victorious situation to the US aggressive foreign policy toward Iran and its desire to isolate the country. This situation remains a priority in Trump’s last days in office. Notwithstanding, as the transition for the administration of Joe Biden begins, it is believed that he would take a more critical approach on Saudi Arabia and the UAE, pressuring them to put an end to the restrictions.

This conflict has turned into a political crisis of retention of power or influence over the region. It is all about Saudi Arabia’s dominance being threatened by a tiny yet very powerful state, Qatar. Although more approaches to lift-up the rift will likely begin to take place and restrictions will gradually relax, this dynamic has been perceived by the international community and the Gulf countries themselves as the new normal. However, if the crisis is ultimately resolved, mistrust and rivalry will remain and will generate complications in a region that is already prone to insurgencies and instability. All the countries involved indeed have more to lose than to gain, but three years have been enough to show that there are ways to turn situations like these around.

La venta de GNL de EEUU a sus vecinos y la exportación desde países de Latinoamérica y el Caribe a Europa y Asia abre nuevas perspectivas

No depender de gaseoductos, sino poder comprar o vender gas natural también a países distantes o sin conexiones terrestres, mejora las perspectivas energéticas de muchas naciones. El éxito del frácking ha generado un excedente de gas que EEUU ha comenzado a vender en muchas partes del mundo, también a sus vecinos hemisféricos, que por su parte cuentan con más posibilidad de elegir proveedor. A su vez, el poder entregar gas en tanqueros ha ampliado la cartera de clientes de Perú y sobre todo de Trinidad y Tobago, que hasta el año pasado eran los dos únicos países americanos, aparte de EEUU, con plantas de licuación. A ellos se añadió Argentina en 2019 y México ha impulsado en 2020 inversiones para sumarse a esta revolución.

![Un carguero de gas natural licuado (GNL; en inglés: LNG) [Pline] Un carguero de gas natural licuado (GNL; en inglés: LNG) [Pline]](/documents/16800098/0/gas-natural-blog.jpg/bc7b4699-c26c-a2d1-2971-f57cbb0345b8?t=1621873574093&imagePreview=1)

▲ Un carguero de gas natural licuado (GNL; en inglés: LNG) [Pline]

ARTÍCULO / Ann Callahan

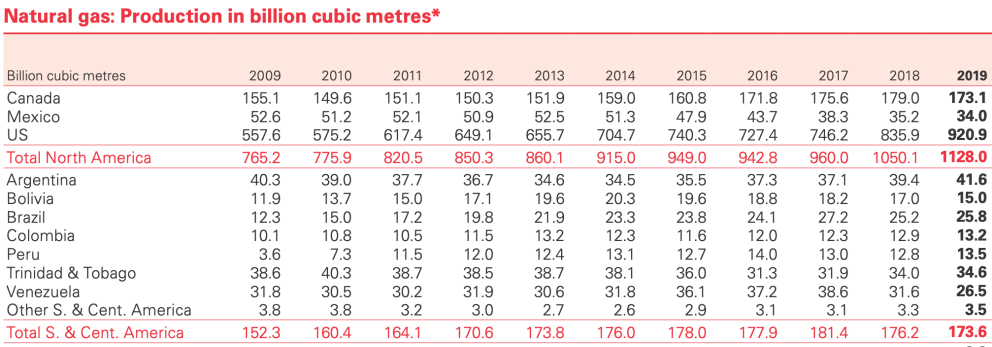

Estados Unidos está conectado por gaseoducto únicamente con Canadá y México, pero está vendiendo gas por barco a una treintena más de países (España, por ejemplo, se ha convertido en un importante comprador). En 2019, EEUU exportó 47.500 millones de metros cúbicos de gas natural licuado (GNL), de los cuales la quinta parte fueron para vecinos americanos, de acuerdo con el informe BP 2020 sobre el sector.

Ocho países de Latinoamérica y el Caribe cuentan ya con plantas de regasificación del gas llegado en carguero en estado líquido: existen tres plantas en México y en Brasil; dos en Argentina, Chile, Jamaica y Puerto Rico, y una en Colombia, República Dominicana y Panamá, según el resumen anual la asociación de países importadores de GNL. A esos países el GNL llega, además desde EEUU, también desde Noruega, Rusia, Angola, Nigeria o Indonesia. Por su parte, dos países exportan GNL a diversas partes del mundo: Trinidad y Tobago, que cuenta con tres plantas de licuación, y Perú, que tiene una (otra entró operativa en Argentina en el último año).

En un intento por mitigar el riesgo de escasez de electricidad debido a un descenso de producción hidroeléctrica por sequía o a otras dificultades de acceso a fuentes energéticas, muchos países de Latinoamérica y el Caribe están recurriendo al GNL. Siendo además una energía más limpia, supone también un atractivo para países que ya están luchando contra el cambio climático. Asimismo, el gas ayuda a superar la discontinuidad de fuentes alternativas, como la eólica o la solar.

En el caso de pequeños países insulares, como los caribeños, que en su mayor parte carecen de fuentes de energía, los programas de cooperación para el desarrollo de terminales de GNL pueden aportarles una cierta independencia respecto a determinados suministros petroleros, como la influencia que sobre ellos ejerció la Venezuela chavista a través de Petrocaribe.

El GNL es un gas natural que ha sido licuado (enfriado a unos -162° C) para su almacenamiento y transporte. El volumen del gas natural en estado líquido se reduce aproximadamente 600 veces en comparación con su estado gaseoso. El proceso hace posible y eficiente su transporte a lugares a los que no llegan los gaseoductos. También es mucho más respetuoso con el medio ambiente, ya que la intensidad de carbono del gas natural es alrededor de un 30% menos que la del diésel u otros combustibles pesados.

El mercado mundial del gas natural ha evolucionado rápidamente en los últimos años. Se espera que las capacidades mundiales de GNL continúen creciendo hasta 2035, encabezadas por Catar, Australia y EEUU. Según el informe de BP sobre el sector, en 2019 la proporción de gas en la energía primaria alcanzó un máximo histórico del 24,2%. Gran parte del crecimiento de la producción de gas en 2019, año en que aumentó en un 3,4%, se debió a las exportaciones adicionales de GNL. Así, el año pasado las exportaciones de GNL crecieron en un 12,7%, hasta alcanzar los 485.100 millones de metros cúbicos.

Plantas de licuación y regasificación en América [Informe GIIGNL]

Auge

Mientras que al comienzo de la primera década de este siglo Estados Unidos se quedó atrás en la producción gasística, el auge del esquisto desde 2009 ha llevado a EEUU a aumentar de forma exponencial la extracción de gas y a desempeñar un papel fundamental en el comercio mundial del producto licuado. Con el transporte relativamente fácil del GNL, EEUU ha podido exportarlo y enviarlo muchos lugares del mundo, siendo América Latina, por su proximidad, una de las regiones que más están notando ese cambio. De los 47.500 millones de metros cúbicos de GNL exportados por EEUU en 2019, 9.700 millones fueron para Latinoamérica; los principales destinos fueron México (3.900 millones), Chile (2.300), Brasil (1.500) y Argentina (1.000).

Si bien la región tiene un potencial de exportación prometedor, dadas sus reservas probadas de gas natural, su demanda supera la producción y debe importar. Venezuela es el país con mayores reservas en Latinoamérica (aunque su potencia gasística es menor que la petrolera), pero su sector de hidrocarburos está en declive y la mayor producción en 2019 correspondió a Argentina, un país emergente en esquisto, seguido de Trinidad y Tobago. Brasil igualó la producción de Venezuela, y luego siguieron Bolivia, Perú y Colombia. En total, la región produjo 207.600 millones de metros cúbicos, mientras que su consumo fue de 256.100 millones.

Algunos países reciben gas por gaseoducto, como es el caso de México y de Argentina y Brasil: el primero recibe gas de EEUU y los segundos de Bolivia. Pero la opción en auge es instalar plantas de regasificación para recibir gas licuado; esos proyectos requieren cierta inversión, normalmente extranjera. El mayor exportador de GNL a la región en 2019 fue EEUU, seguido de Trinidad y Togado, que por su bajo consumo doméstico prácticamente exporta toda su producción: de sus 17.000 millones de metros cúbicos de GNL, 6.100 fueron para países latinoamericanos. El tercer país exportador es Perú, que destinó sus 5.200 millones de metros cúbicos a Asia y Europa (no vendió en el propio continente). A las exportaciones en 2019 se sumó por primera vez Argentina, aunque con una baja cantidad, 120 millones de metros cúbicos, casi todos destinados a Brasil.

La región importó en 2019 un total de 19.700 millones de metros cúbicos de GNL. Los principales compradores fueron México (6.600 millones de metros cúbicos), Chile (3.300 millones), Brasil (3.200) y Argentina (1.700).

Algunos de los que importaron cantidades más reducidas luego reexportaron parte de los suministros, como hicieron República Dominicana, Jamaica y Puerto Rico, en general con Panamá como principal destino.

Tablas extraídas del informe Statistical Review of World Energy 2020 [BP]

Por países

México es el mayor importador de GNL de América Latina; sus suministros proceden sobre todo de EEUU. Durante mucho tiempo, México ha dependido de los envíos de gas de su vecino del norte llegados a través de gaseoductos. Sin embargo, el desarrollo del GNL ha abierto nuevas perspectivas, pues la ubicación del país le puede ayudar a impulsar ambas capacidades: la mejora de sus conexiones por gaseoducto con EEUU le puede permitir a México disponer de un surplus de gas en terminales del Pacífico para la reexportación de GNL a Asia, complementando la ausencia por ahora de plantas de licuación en la costa oeste estadounidense.

La posibilidad de reexportar desde la costa pacífica mexicana al gran y creciente mercado del GNL de Asia –sin necesidad, por tanto, de que los tanqueros tengan que atravesar el Canal de Panamá– supone un gran atractivo. El Departamento de Energía de EEUU concedió a comienzos de 2019 dos autorizaciones al proyecto Energía Costa Azul de México para reexportar gas natural derivado de EEUU en forma de GNL a aquellos países que no tienen un acuerdo de libre comercio (TLC) con Washington, según se recoge en el informe de 2020 del Grupo Internacional de Importadores de Gas Natural Licuado (GIIGNL).

Durante la última década, Argentina ha estado importando GNL de EEUU; sin embargo, en años recientes ha reducido sus compras en más de un 20% al haber aumentado la producción nacional de gas gracias a la explotación de Vaca Muerta. Esos yacimientos han permitido también reducir las compras de gas a la vecina Bolivia y vender más gas, igualmente por gaseoducto, a sus también vecinos Chile y Brasil. Además, en 2019 comenzó exportaciones de GNL desde la planta de Bahía Blanca.

Con el bombeo de gas de Argentina a su vecino Chile, en 2019 las importaciones chilenas de GNL disminuyeron a su grado más bajo en tres años, aunque sigue siendo uno de los compradores importantes de América Latina, que ha cambiado Trinidad y Tobago por EEUU como proveedor preferente. Cabe señalar, sin embargo, que la capacidad de las exportaciones de Argentina depende de los niveles de los flujos internos, especialmente durante las temporadas de invierno, en las que la calefacción generalizada es una necesidad para los argentinos.

En el último decenio, la importación de GNL por parte del Brasil ha variado significativamente de un año a otro. No obstante, se proyecta que será más consistente en la dependencia del GNL por lo menos hasta la próxima década, mientras se desarrollan energía renovables. En Brasil, el gas natural se utiliza en gran medida como refuerzo de la energía hidroeléctrica brasileña.

Además de Brasil, Colombia también considera el GNL como un recurso ventajoso para respaldar su sistema hidroeléctrico en períodos bajos. En su costa pacífica, Colombia está planeando actualmente un segundo terminal de regasificación. Ecopetrol, la empresa estatal de hidrocarburos, destinará 500 millones de dólares a proyectos no convencionales de gas, además de petróleo. Junto con la autorización del gobierno para permitir el frácking, se proyecta que las reservas actualmente estancadas se incrementen.

Bolivia también posee un importante potencial de producción de gas natural y es el país de la región cuya economía es más dependiente de este sector. Tiene la ventaja de la infraestructura ya existente y el tamaño de los mercados de gas vecinos; no obstante, se enfrenta a la competencia de producción de Argentina y Brasil. Asimismo, al ser un país sin acceso al mar queda limitado en la comercialización de GNL.

Aunque Perú es el séptimo país en producción de gas natural de la región, se ha convertido en el segundo exportador de GNL. El menor consumo interno, comparado con otros mercados vecinos, le ha llevado a desarrollar la exportación de GNL, reforzando su perfil de nación enfocada hacia Asia.

Por su parte, Trinidad y Tobago, ha acomodado su producción gasística a su condición de país insular, por lo que basa su exportación de hidrocarburos mediante tanqueros, lo que le da acceso a mercados distantes. Es el primer exportador de la región y el único que tiene clientes en todos los continent

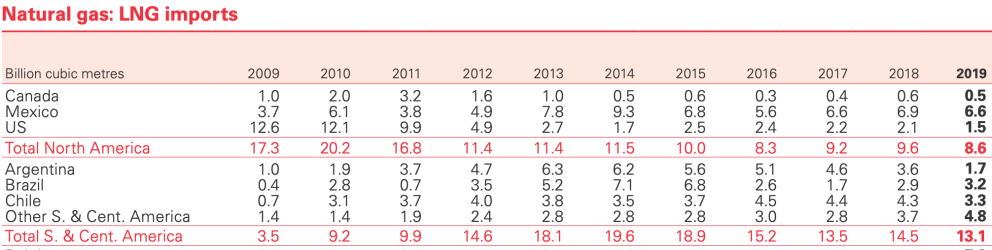

As the United States considers moving its AFRICOM from Germany, the relocation to US Navy Station Rota in Spain offers some opportunities and benefits

The United States is considering moving its Africa Command (USAFRICOM) to a place closer to Africa and the US base in Rota, Spain, in one of the main alternatives. This change in location would undoubtedly benefit Spain, but especially the United States, we argue. Over the past years, there has been a ‘migration’ of US troops from Europe, particularly stationed in Germany, to their home country or other parts of the hemisphere. In this trend, it has been considered to move AFRICOM from “Kelly Barracks,” in Stuttgart, Germany, to Rota, located in the province of Cádiz, near the Gibraltar Strait.

![Entrance to the premises of the US Navy Station Rota [US DoD] Entrance to the premises of the US Navy Station Rota [US DoD]](/documents/16800098/0/rota-blog.jpg/3d6dc4ec-a235-79a3-e478-4706f1f129e7?t=1621877332236&imagePreview=1)

▲ Entrance to the premises of the US Navy Station Rota [US DoD]

ARTICLE / José Antonio Latorre

The US Africa Command is the military organization committed to further its country’s interests in the African continent. Its main goal is to disrupt and neutralize transnational threats, protect US personnel and facilities, prevent and mitigate conflict, and build defense capability and capacity in order to promote regional stability and prosperity, according to the US Department of Defense. The command currently participates in operations, exercises and security cooperation efforts in 53 African countries, compromising around 7,200 active personnel in the continent. Its core mission is to assist African countries to strengthen defense capabilities that address security threats and reduce threats to US interests, as the command declares. In summary, USAFRICOM “is focused on building partner capacity and develops and conducts its activities to enhance safety, security and stability in Africa. Our strategy entails an effective and efficient application of our allocated resources, and collaboration with other U.S. Government agencies, African partners, international organizations and others in addressing the most pressing security challenges in an important region of the world.” The headquarters are stationed in Stuttgart, Germany, more than 1,500 kilometers away from Africa. The United States has considered to move the command multiple times for logistical and strategic reasons, and it might be the time the government takes the decision.

Bilateral relations between Spain and the United States

When it comes to the possible relocation of AFRICOM, the main competitor is Italy, with its military base in Sigonella. An ally that has been increasingly important to the United States is Morocco, which has offered to accommodate more military facilities as its transatlantic ally continues to provide the North African country with weapons and armament. However, it is important to remember that the United States and Spain cooperate in NATO, fortifying their security and defense relations in the active participation in international missions. Although Italy also belongs to the same organizations, it is important to emphasize the strategic advantages of placing the command in Rota as opposed to in Sigonella: Rota it is a key point which controls the Strait of Gibraltar and contains much of the needed resources for the relocation. Spain combines the fact that it is a European Union and NATO member, while it has territories in Africa and shares key interests in the region due to multiple current and historical reasons. Spain acts as the bridge with Northern Africa in the West. This is an argument that neither Morocco nor Italy can offer.

The relations between Spain and the United States are regulated by the Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement and Agreement on Defense Cooperation (1988), following the Military Facilities in Spain: Agreement Between the United States and Spain Pact (1953), enacted to formalize the alliance in common objectives and where Spain permits the United States to use facilities in its territory. There are two US military bases in Spanish territory: US Air Force Base Morón and US Naval Station Rota. Both locations are strategic as they are in the south, essential for their proximity to the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea and, particularly, to Africa. Although it is true that Morocco offers the same strategic advantages as Rota, it is important to take into account the similarities in culture, the Western point of view, the shared strategies in NATO, and the shared democratic and societal values that the Spanish alternative offers. The political stability that Spain can offer as part of the European Union and as a historical ally to the United States is not comparable with Morocco’s.

If a relocation is indeed in the interest of the United States, then Spain is the ideal country for the placement of the command. Since the consideration is on the Naval Station in Rota, then the article will evidently focus on this location.

Rota as the ideal candidate

Rota Naval Station was constructed in 1953 to heal bilateral relations between both countries. It was placed in the most strategic position in Spain, and one of the most in Europe. Naval Station Rota is home to Commander, Naval Activities Spain (COMNAVACT), responsible for US Naval Activities in Spain and Portugal. It reports directly to Commander, Navy Region Europe, Africa and Southwest Asia located in Naples, Italy. There are around 3,000 US citizens in the station, a number expected to increase by approximately 2,000 military personnel and dependents due to the rotation of “Aegis” destroyers.

Currently, the station provides support for NATO and US ships as well as logistical and tactical aid to US Navy and US Air Force units. Rota is key for military operations in the European theatre, but obviously unique to interests in Africa. To emphasize the importance of the facility, the US Department of Defense states: “Naval Station (NAVSTA) Rota plays a crucial role in supporting our nation’s objectives and defense, providing unmatched logistical support and strategic presence to all of our military services and allies. NAVSTA Rota supports Naval Forces Europe Africa Central (EURAFCENT), 6th Fleet and Combatant Command priorities by providing airfield and port facilities, security, force protection, logistical support, administrative support and emergency services to all U.S. and NATO forces.” Clearly, Naval Station Rota is a US military base that will be maintained and probably expanded due to its position near Africa, an increasingly important geopolitical continent.

Spain’s candidacy for accommodating USAFRICOM

Why would Spain be the ideal candidate in the scenario that the United States decides to change its USAFRICOM location? Geographically speaking, Spain actually possesses territories in Africa: Ceuta, Melilla, “Plazas de Soberanía,” and Canary Islands. Legally, these territories are fully incorporated as autonomous cities and an autonomous community, respectively.

Secondly, the bilateral relations between Spain and the United States, from the perspective of security and defense, have been very fluid and dynamic, with benefits for both. After the 1953 convention between both Western countries, there have been joint operations co-chaired by the Secretary General of Policy of Defense (SEGENPOL) of the Spanish Ministry of Defense and the Under Secretary General for Defense Policy (USGDP) in the United States Department of Defense. Both offices plan and execute plans of cooperation that include: The Special Operations “Flint Lock” Exercise in Northern Africa, bilateral exercises with paratrooping units, officer exchanges for training missions, etc. It is important to add to this list that Spain and the United States share a special relationship when it comes to officers, because all three branches (Air Force, Army, Navy) have exchange programs in military academies or bases.

Finally, when it comes to Spain, it must be noted that the fluid relationship maintained between both countries has created a very friendly and stable environment, particularly in the area of Defense. Spain is a country of the European Union, a long-time loyal ally to the United States in the fight against terrorism and in the shared goals of strengthening the transatlantic partnership. This impeccable alliance offers stability, mutual confidence and reciprocity in terms of Defense. The United States Africa Command needs a solid “host”, committed to participating in active operations in Africa, and there is no better candidate than Spain. Its historical relationship with the countries in Northern Africa is important to take into account for perspective and information gathering. The Spanish Armed Forces is the most valued institution in society, and it is for sure more than capable of accommodating USAFRICOM to its needs in the South of the country, as it has always done for the United States, however, this remains a fully political decision.

The United States’ position

Rota is an essential strategic point in Europe, and increasingly, in the world. The US base is well known for its support to missions from the US Navy and the US Air Force, and its responsibility only seems to increase. In 2009, the United States sent four destroyers from the Naval Base in Norfolk, Virginia, to Rota, as well as a large force of US Naval Construction units, known as “Seabees” and US Marines. It is also worth noting that NATO has its most important pillar of an antimissile shield in Rota, given the geographical ease and the adequate facilities. From the perspective of infrastructure, on-hand station services, security and stability, Rota is the ideal location of the USAFRICOM compared to Morocco.

Moreover, Rota is, and continues to be, a geographical pinnacle for flights from the United States heading to the Middle East, particularly Iraq and Afghanistan. Most recently, USS Hershel “Woody” Williams arrived in Rota and joined NATO allies in the Grand African Navy Exercise for Maritime Operations (NEMO) that took place in the Gulf of Guinea in the beginning of October of 2020. In terms of logistics, Rota is more than equipped to host a headquarters of the magnitude of USAFRICOM and it would be economically efficient to relocate the personnel and their families as the station counts with a US Naval Clinic, schools, a commissary, a Navy Exchange, and other services.

The United States has not made a formal proposition to transfer Africa Command to Rota, but if there is a change of location, it is one of the main candidates. As Spain’s Minister of Foreign Affairs González Laya stated, the possible transfer of USAFRICOM to Rota is a decision that corresponds only to the United States, but Spain remains fully committed with its transatlantic ally. González Laya emphasized that “Spain has a great commitment to the United States in terms of security and defense, and it has been demonstrated for many years from Rota and Morón.” The minister reminded that Spain maintains complicity and joint work in the fight against terrorism in the Sahel with an active participation in European and international operations in terms of training local armies to secure order. A perfect example of the commitment is Spain’s presidency of the Sahel Alliance, working for a secure Sahel under the pillars of peace and development.

In 2007, when USAFRICOM was established, it could have been reasonable to install the headquarters in Germany, but now geographical proximity is key, and what better country for hosting the command than Spain, which has territories in the continent. The United States already has a fully equipped military base in Rota, and it can count on Spain to guarantee a smooth transition. Spain’s active participation in missions, her alliance with the United States and her historic and political ties with Africa are essential reasons to heavily consider Rota as the future location of USAFRICOM. Spain has been, and will continue to be, a reliable ally in the war against terrorism and the fight for peace and security. Spain is a country that believes in democracy, freedom and justice, like the United States. It is a country that has sacrificed soldiers in the face of freedom and has stood shoulder to shoulder with its transatlantic friend in the most difficult of moments. As a Western country, both countries have been able to work together and achieve many common objectives, and this will only evolve. As the interests in Africa expand, it is undoubtedly important to choose the best military facility to accommodate the command’s military infrastructure as well as its personnel and their families. The United States, in benefit of its strategic objectives, would be making a very effective decision if it decides to move the Africa Command to Rota, Spain.

El comercio indio con la región se ha multiplicado por veinte desde el año 2000, pero es solo un 15% del flujo comercial con China

El rápido derrame comercial, crediticio e inversor de China en Latinoamérica en la primera década de este siglo hizo pensar que India, si pretendía seguir los pasos de su rival continental, tal vez podría protagonizar un desembarco similar en la segunda década. Esto no ha ocurrido. India ha incrementado ciertamente su relación económica con la región, pero está muy lejos de la desarrollada por China. Incluso los flujos comerciales de los países latinoamericanos son mayores con Japón y Corea del Sur, si bien es previsible que en unos años sean sobrepasados por los mantenidos con India dado su potencial. En un contexto internacional de confrontación entre EEUU y China, India emerge como opción no conflictiva, además especializada en servicios de IT tan necesarios en un mundo que ha descubierto la dificultad de movilidad por el Covid-19.

ARTÍCULO / Gabriela Pajuelo

Históricamente India ha prestado poca atención a Latinoamérica y el Caribe; lo mismo había ocurrido con China, al margen de episodios de migración desde ambos países. Pero el surgimiento de China como gran potencia y su desembarco en la región hizo preguntarse al Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID) en un informe de 2009 si, tras ese empuje chino, India iba ser “la próxima gran cosa” para Latinoamérica. Aunque las cifras indias fueran a quedar por detrás de las chinas, ¿podía India convertirse en un actor clave en la región?

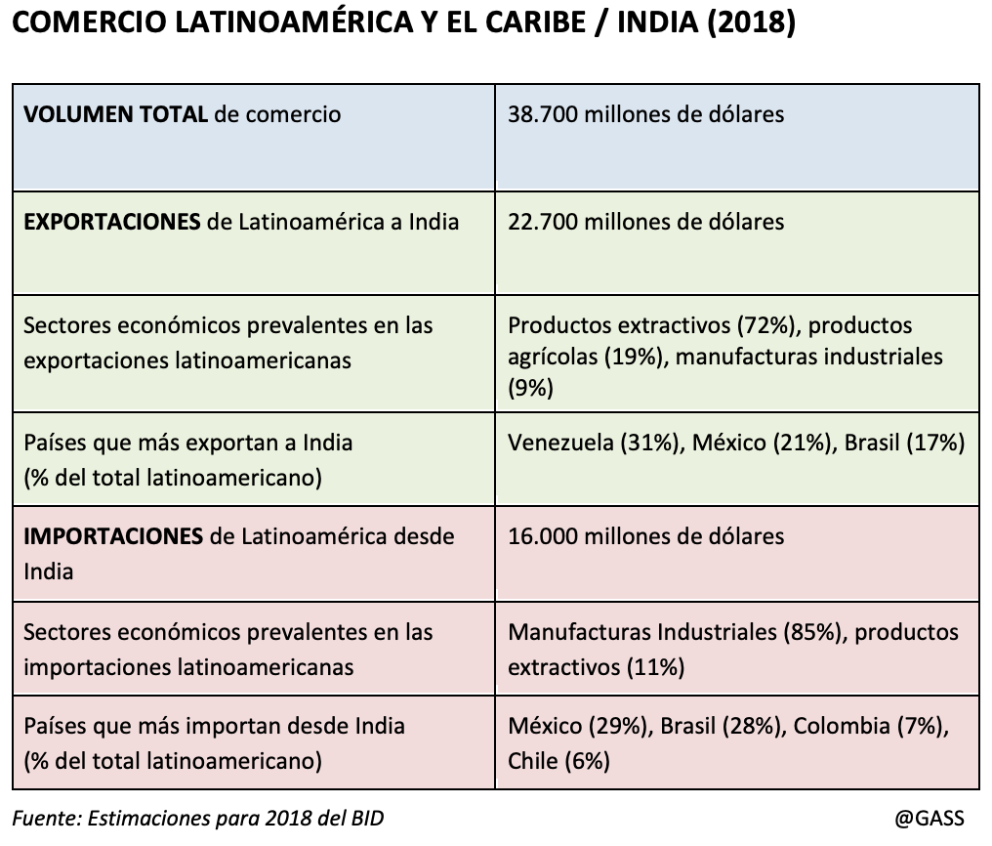

La relación de los países latinoamericanos con Nueva Delhi ciertamente ha aumentado. Incluso Brasil ha desarrollado una especial vinculación con India gracias al club de los BRICS, como lo puso de manifiesto la visita que el presidente brasileño Jair Bolsonaro hizo en enero de 2020 a su homólogo Narendra Modi. En las dos últimas décadas, el comercio de India con la región se ha multiplicado por veinte, pasando de los 2.000 millones de dólares en el año 2000 a los casi 40.000 de 2018, como constató el año pasado un nuevo informe del BID.

Ese volumen, no obstante, queda muy por debajo del flujo comercial con China, del que constituye solo un 15%, pues si los intereses indios en Latinoamérica han aumentado, en mayor medida lo han seguido haciendo los chinos. La inversión desde ambos países en la región es incluso más desproporcionada: entre 2008 y 2018, la inversión de India fue de 704 millones de dólares, frente a los 160.000 millones de China.

Incluso el incremento comercial indio tiene una menor imbricación regional de lo que podrían aparentar las cifras globales. Del total de 38.700 millones de dólares de transacciones en 2018, 22.700 corresponden a exportaciones latinoamericanas y 16.000 a importaciones de productos indios. Las compras indias han superado ya a las importaciones realizadas desde Latinoamérica por Japón (21.000 millones) y Corea del Sur (17.000 millones), pero en gran parte se deben a la adquisición de petróleo de Venezuela. Sumadas las dos direcciones de flujo, el comercio de la región con Japón y con Corea sigue siendo mayor (en torno a los 50.000 millones de dólares en ambos casos), pero las posibilidades de crecimiento de la relación comercial con India son claramente mayores.

No solo hay interés por parte de los países americanos, sino también desde India. “Latinoamérica tiene una fuerza de trabajo joven y calificada, y es una zona rica en reservas de recursos naturales y agrícolas”, ha señalado David Rasquinha, director general del Banco de Exportaciones e Importaciones de la India.

Última década

Los dos informes del BID citados reflejan bien el salto dado en las relaciones entre ambos mercados en la última década. En el de 2009, bajo el título “India: Oportunidades y desafíos para América Latina”, la institución interamericana presentaba las oportunidades que ofrecían los contactos con India. Aunque apostaba por incrementarlos, el BID se mostraba inseguro sobre la evolución de una potencia que durante mucho tiempo había apostado por la autarquía, como en el pasado habían hecho México y Brasil; no obstante, parecía claro que el gobierno indio finalmente había tomado una actitud más conciliadora hacia la apertura de su economía.

Diez años después, el informe titulado “El puente entre América Latina y la India: Políticas para profundizar la cooperación económica” se adentraba en las oportunidades de cooperación entre ambos actores y denotaba la importancia de estrechar lazos para favorecer la creciente internacionalización de la región latinoamericana, a través de la diversificación de socios comerciales y acceso a cadenas productivas globales. En el contexto de la Asian Century, el flujo de intercambio comercial y de inversión directa había incrementado exponencialmente desde niveles anteriores, resultado en gran medida de la demanda de materias primas latinoamericanas, algo que suele levantar críticas, dado que no fomenta la industria de la región.

La nueva relación con India presenta la ocasión de corregir algunas de las tendencias de la interacción con China, que se ha centrado en inversión de empresas estatales y en préstamos de bancos públicos chinos. En la relación con India hay una mayor participación de la iniciativa privada asiática y una apuesta por los nuevos sectores económicos, además de la contratación de personal autóctono, incluso para los niveles de gestión y dirección.

De acuerdo con el Gerente del Sector de Integración y Comercio del BID, Fabrizio Opertti, es crucial “el desarrollo de un marco institucional eficaz y de redes empresariales”. El BID sugiere posibles medidas gubernamentales como el incremento de la cobertura de acuerdos de comercio e inversiones, el desarrollo de actividades de promoción comercial proactivas y focalizadas, el impulso de inversiones en infraestructura, la promoción de reformas en el sector logístico, entre otras.

Contexto post-Covid

El cuestionamiento de las cadenas de producción globales y, en última instancia, de la globalización misma a causa de la pandemia del Covid-19, no favorece el comercio internacional. Además, la crisis económica de 2020 puede tener un largo efecto en Latinoamérica. Pero precisamente en este marco mundial la relación con India puede ser especialmente interesante para la región.

Dentro de Asia, en un contexto de polarización sobre los intereses geopolíticos de China y Estados Unidos, India emerge como un socio clave, se podría decir que hasta neutral; algo que Nueva Delhi podría utilizar estratégicamente en su aproximación a diferentes áreas del mundo y en concreto a Latinoamérica.

Aunque “India no tiene bolsillos tan grandes como los chinos”, como dice Deepak Bhojwani, fundador de la consultora Latindia[1], en relación a la enorme financiación pública que maneja Pekín, India puede ser el origen de interesantes proyectos tecnológicos, dada la variedad de empresas y expertos de informática y telecomunicaciones con los que cuenta. Así, Latinoamérica puede ser objeto de la “technology foreign policy” de un país que, de acuerdo con su Ministerio de Electrónica y IT, tiene ambición de crecer su economía digital a “un billón de dólares hacia 2025”. Nueva Delhi focalizará sus esfuerzos en influenciar este sector económico a través de NEST (New, Emerging and Strategic Technologies), promoviendo un mensaje indio unificado sobre tecnologías emergentes, como gobierno de datos e inteligencia artificial, entre otros. La pandemia ha puesto de relieve la necesidad que Latinoamérica tiene de una mayor y mejor conectividad.

Existen dos perspectivas para la expansión de la influencia india en el continente. Una es el camino obvio de fortalecer su existente alianza con Brasil, en el seno de los BRICS, cuya presidencia pro tempore India tiene este año. Eso debiera dar lugar a una vinculación más diversificada con Brasil, el mercado más grande de la región, especialmente en la cooperación científica y tecnológica, en los campos de IT, farmacéutico y agroindustrial. “Ambos gobiernos se comprometieron a expandir el comercio bilateral a 15.000 millones de dólares para 2022. A pesar de las dificultades que trajo la pandemia, estamos persiguiendo esta ambiciosa meta”, afirma André Aranha Corrêa do Lago, actual embajador de Brasil en India.

Por otro lado, se podría dar un esfuerzo mayor en la diplomacia bilateral, insistiendo en los lazos preexistentes con México, Perú y Chile. Este último país e India están negociando un acuerdo de comercio preferencial y la firma del Tratado Bilateral de Protección de Inversiones. También puede ser de interés un acercamiento a Centroamérica, que todavía carece de misiones diplomáticas indias. Son pasos necesarios si, marcando de cerca los pasos de China, India quiere ser la “next big thing” para Latinoamérica.

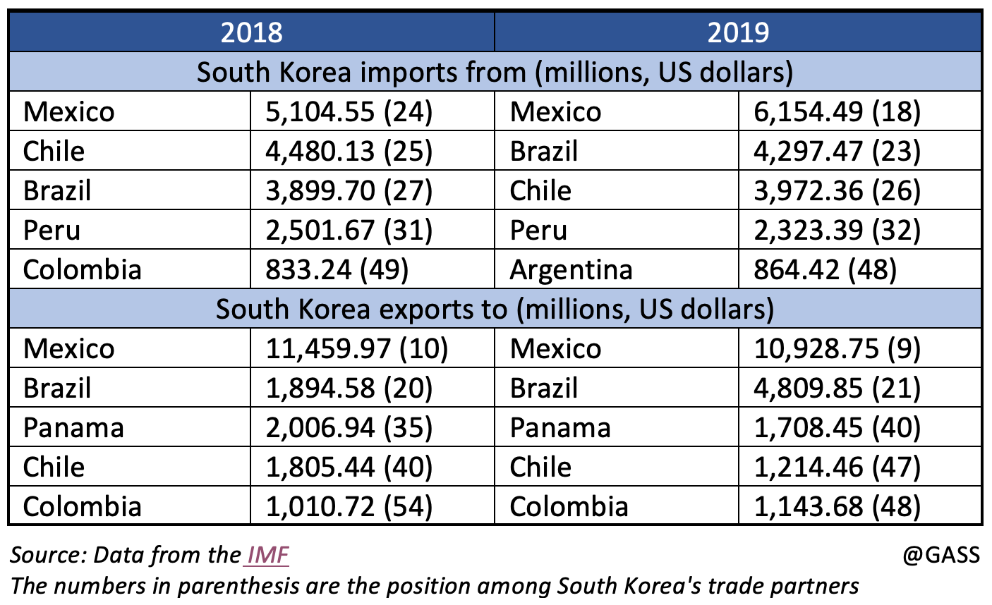

The increase in South Korean trade with Latin American countries has allowed the Republic of Korea to reach Japan's exchange figures with the region

Throughout 2018, South Korea's trade with Latin America exceeded USD 50 billion, putting itself at the same level of trade maintained by Japan and even for a few months becoming the second Asian partner in the region after China, which had flows worth USD 300 billion (half of the US trade with its continental neighbors). South Korea and Japan are ahead of India's trade with Latin America (USD 40 billion).

ARTICLE / Jimena Villacorta

Latin America is a region highly attractive to foreign markets because of its immense natural resources which include minerals, oil, natural gas, and renewable energy not to mention its agricultural and forest resources. It is well known that for a long time China has had its eye in the region, yet South Korea has also been for a while interested in establishing economic relations with Latin American countries despite the spread of new protectionism. Besides, Asia's fourth largest economy has been driving the expansion of its free trade network to alleviate its heavy dependence on China and the United States, which together account for approximately 40% of its exports.

The Republic of Korea has already strong ties with Mexico, but Hong Nam-ki, the South Korean Economy and Finance Minister, has announced that his country seeks to increase bilateral trade between the regions as it is highly beneficial for both. “I am confident that South Korea's economic cooperation with Latin America will continue to persist, though external conditions are getting worse due to the spread of new protectionism”, he said. While Korea's main trade with the region consists of agricultural products and manufacturing goods, other services such as ecommerce, health care or artificial intelligence would be favorable for Latin American economies. South Korean investment has significantly grown during the past decades, from USD 620 million in 2003, to USD 8.14 billion in 2018. Also, their trade volume grew from USD 13.4 billion to 51.5 billion between the same years.

Apart from having strong ties with Mexico, South Korea signed a Free Trade Agreement with the Central American countries and negotiates another FTA with the Mercosur block. South Korea would like to join efforts with other Latin American countries in order to breathe life into the Trans-Pacific Partnership, bringing the US again into the negotiations after a change of administration in Washington.

Mexico

Mexico and South Korea’s exports and imports have increased in recent years. Also, between 1999 and 2015, the Asian country’s investments in Mexico reached USD 3 billion. The growth is the result of tied partnerships between both nations. Both have signed an Agreement for the Promotion and Reciprocal Protection of Investments, an Agreement to Avoid Income Tax Evasion and Double Taxation and other sectoral accords on economic cooperation. Both economies are competitive, yet complementary. They are both members of the G20, the OECD and other organizations. Moreover, both countries have high levels of industrialization and strong foreign trade, key of their economic activity. In terms of direct investment from South Korea in Mexico, between 1999 and June 2019, Mexico received USD 6.5 billion from Korea. There are more than 2,000 companies in Mexico with South Korean investment in their capital stock, among which Samsung, LG, KORES, KEPCO, KOGAS, Posco, Hyundai and KIA stand out. South Korea is the 12th source of investment for Mexico worldwide and the second in Asia, after Japan. Also, two Mexican multinationals operate in South Korea, Grupo Promax and KidZania. Mexico’s main exports to South Korea are petrol-based products, minerals, seafood and alcohol, while South Korea’s main exports to Mexico are electronic equipment like cellphones and car parts.

Mercosur

Mercosur is South America’s largest trading economic bloc, integrated by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. With a GDP exceeding USD 2 trillion, it is one of the major suppliers of raw materials and agricultural and livestock products. South Korea and Mercosur launched trade negotiations on May 2018, in Seoul. Actually, the Southern Common Market and the Republic of Korea have been willing to establish a free trade agreement (FTA) since 2005. These negotiations have taken a long time due to Mercosur’s protectionism, so the Asian country has agreed on a phased manner agreement to reach a long-term economic cooperation with the bloc. The first round of negotiations finally took place in Montevideo, the Uruguayan capital, in September 2018. Early this year, they met again in Seoul to review the status of the negotiations for signing the Mercosur-Korea trade agreement. This agreement covers on the exchange of products and services and investments, providing South Korean firms faster access to the Latin American market. The Asian tiger main exports to South America are industrial goods like auto parts, mobile devices and chips, while its imports consist of mineral resources, agricultural products, and raw materials like iron ore.

Among Mercosur countries, South Korea has already strong ties with Brazil. Trade between both reached USD 1.70 billion in 2019. Also, South Korean direct investments totaled USD 3.69 billion that same year. With the conclusion of the trade agreement with the South American block, Korean products exported to Brazil would benefit from tariff eliminations, as would Korean cargo trucks, and other products going to Argentina. It would also be the first Asian country to have established a trade agreement with Mercosur.

Central America

South Korea is the first Asian-Pacific country to have signed a FTA with Central American countries (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama). According to Kim Yong-beom, South Korean Deputy Minister of Economy and Finance, bilateral cooperation will benefit both regions as state regulatory powers won’t create unnecessary barriers to commercial exchange between both. “The FTA will help South Korean companies have a competitive edge in the Central American region and we can establish a bridgehead to go over to the North and South American countries through their FTA networks”, said Kim Hak-do, Deputy Trade Minister, when the agreement was reached in November 2016. Also, both economic structures will be complimented by each other by encouraging the exchange between firms from both regions. They signed the FTA on February 21st, 2018, after eighth rounds of negotiations from June 2015 to November 2016 that took place in Seoul, San Salvador, Tegucigalpa and Managua. Costa Rica also signed a memorandum of understanding with South Korea to boost trade cooperation and investment. This partnership will create new opportunities for both regions. South Korean consumers will have access to high-quality Central American products like grown coffee, agricultural products, fruits like bananas, and watermelons, at better prices and free of tariffs and duties. Additionally, Central American countries will have access to goods like vehicle parts, medicines and high-tech with the same advantages. Besides unnecessary barriers to trade, the FTA will promote fair marketing, ease the exchange of goods and services, to encourage the exchange businesses to invest in Central America and vice versa. Moreover, having recently joined the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI) as an extra-regional member, has reinforced the development of socio-economic projects around the region.

Opportunity

The Republic of Korea faces challenges related to the scarcity of natural resources, there are others, such as slower growth in recent decades, heavy dependence on exports, competitors like China, an aging population, large productivity disparities between the manufacturing and service sectors, and a widening income gap. Inasmuch, trade between Latin America and the Caribbean and the Republic of Korea, though still modest, has been growing stronger in recent years. Also, The Republic of Korea has become an important source of foreign direct investment for the region. The presence of Korean companies in a broad range of industries in the region offers innumerable opportunities to transfer knowledge and technology and to create links with local suppliers. FTAs definitely improve the conditions of access to the Korean market for the region's exports, especially in the most protected sectors, such as agriculture and agroindustry. The main challenge for the region in terms of its trade with North Korea remains export diversification. The region must simultaneously advance on several other fronts that are negatively affecting its global competitiveness. It is imperative to close the gaps in infrastructure, education and labor training.

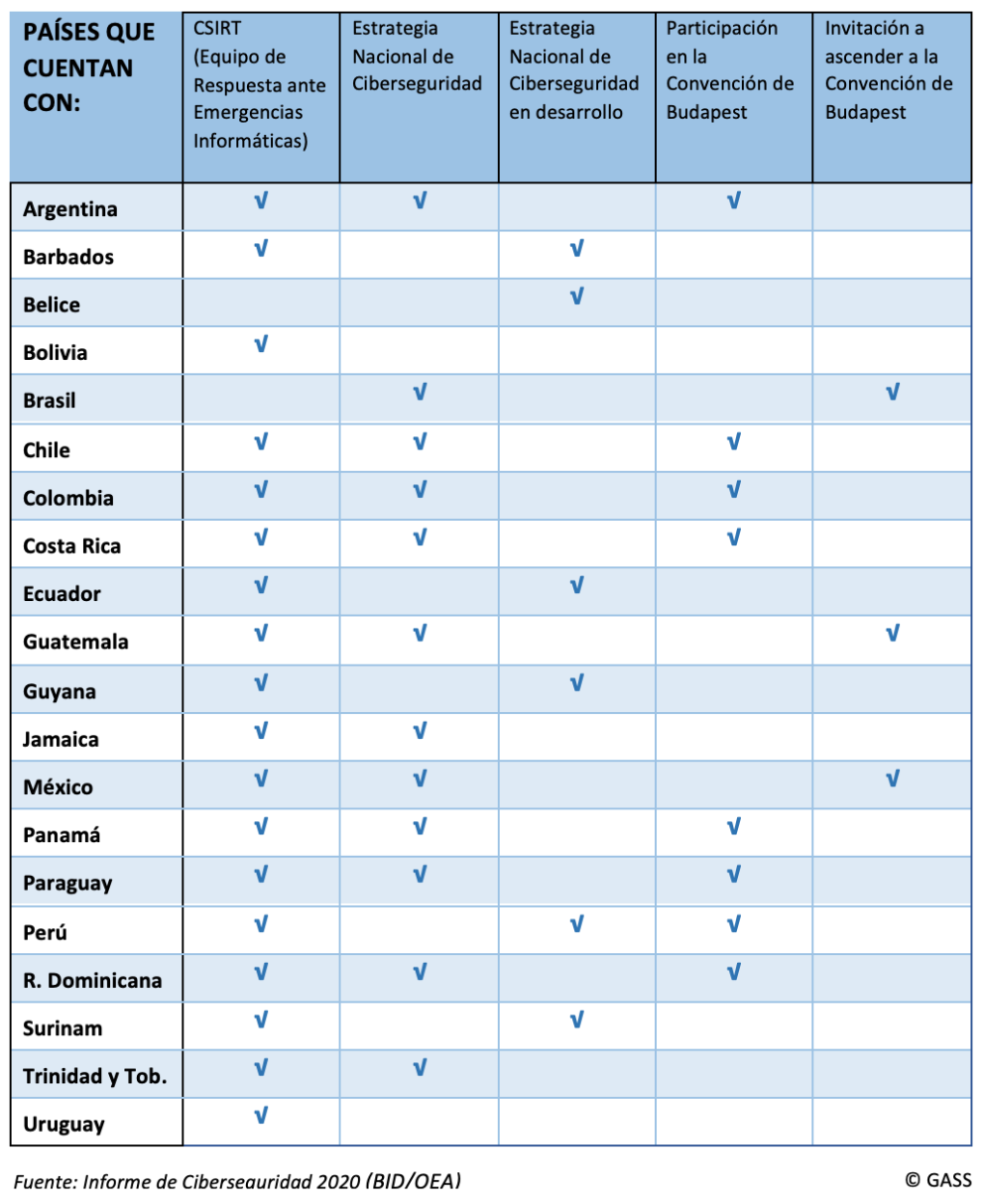

Un tercio de los países ha desarrollado una estrategia nacional de ciberseguridad, pero las capacidades movilizadas son mínimas

Una docena de países latinoamericanos han desarrollado ya una estrategia nacional de ciberseguridad, pero en general las capacidades movilizadas en la región para hacer frente al crimen y a los ataques cibernéticos son de momento reducidas. En un continente con alto uso de las redes sociales, pero al mismo tiempo con algunos problemas de red eléctrica y acceso a internet que dificultan una reacción ante los ciberataques, el riesgo de que los extendidos grupos de crimen organizado recurran cada vez más a la cibernética es alto.

ARTÍCULO / Paula Suárez

En los últimos años, la globalización se ha abierto camino en todas partes del mundo, y con ello han surgido varias amenazas en el ámbito del ciberespacio, lo que requiere especial tratamiento por parte de los gobiernos de todos los estados. A nivel global y no solo en Latinoamérica, los principales campos que se ven amenazados en cuanto a seguridad cibernética son, esencialmente, el delito informático, las intrusiones en redes y las operaciones políticamente motivadas.

Los últimos informes sobre ciberseguridad en América Latina y el Caribe realizados conjuntamente por el Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID) y la Organización de los Estados Americanos (OEA), indican que un tercio de los países de la región han comenzado a dar algunos pasos para hacer frente a los crecientes riesgos en ciberseguridad. No obstante, también constatan que los esfuerzos son de momento pequeños, dada la general falta de preparación ante la amenaza del cibercrimen; además plantean la necesidad de una reforma en las políticas de protección para los años venideros, especialmente con los problemas que han salido a relucir con la crisis del Covid-19.

El BID y la OEA (OEA) han colaborado en distintas ocasiones para dar a conocer la situación y concienciar a la población sobre los problemas de ciberseguridad, que han ido aumentando conforme la globalización se ha hecho parte de la vida cotidiana y las redes sociales e internet se integran de manera más profunda en nuestro día a día. Para ocuparse de esta nueva realidad, ambas instituciones han creado un Observatorio de Ciberseguridad de la región, que ha publicado varios estudios.

Si hasta el informe de 2016 la ciberseguridad era un tema poco discutido en la región, actualmente con el aumento de la tecnología en América Latina y el Caribe ha pasado a ser un tema de interés por el que los estados tienden a preocuparse cada vez más, y por ello, a implementar las medidas pertinentes, como se destaca en el informe de 2020.

El transporte, las actividades educativas, las transacciones financieras, muchos servicios como el suministro de alimentos, agua o energía y otras muchas actividades requieren de políticas de ciberseguridad para proteger los derechos civiles en el ámbito digital tales como el derecho a la privacidad, muchas veces violados por el uso de estos sistemas como arma.

No solo en el ámbito social, sino también en el económico, la inversión en ciberseguridad es fundamental para evitar los daños que ocasiona el crimen en línea. Para el Producto Interior Bruto de muchos países de la región, los ataques a la infraestructura pueden suponer desde un 1% hasta un 6% del PIB en el caso de ataques a infraestructura crítica, lo que se traduce en incompetencia por parte de estos países para identificar los peligros cibernéticos y para tomar las medidas necesarias para combatirlos.

Según el estudio previamente mencionado, 22 de los 32 países que se analizan son considerados con capacidades limitadas para investigar los delitos, solo 7 tienen un plan de protección de su infraestructura crítica, y 18 de ellos han establecido el llamado CERT o CSIRT (equipo de respuesta a incidentes o emergencias de seguridad informática). Estos sistemas no son desarrollados actualmente de forma uniforme en la región, y les falta capacidad de actuación y madurez para suponer una respuesta adecuada antes las amenazas en la red, pero su implementación es necesaria y, cada vez más, cuentan con el apoyo de instituciones como la OEA para su mejora.

En este ámbito, el Foro de Equipos de Seguridad y de Respuesta a Incidentes (FIRST) tiene un trabajo clave, por la gran necesidad en esta región, para asistir a los gobiernos y que estos puedan beneficiarse de la identificación de amenazas cibernéticas y los mecanismos de seguridad estratégica de la asociación, principalmente para proteger las economías de estos países.

Como ya ha sido mencionado, la conciencia de la necesidad de dichas medidas ha ido aumentando conforme a los ataques cibernéticos también lo han hecho, y países como Colombia, Jamaica, Trinidad y Tobago y Panamá han establecido una debida estrategia para combatir estos daños. Por el contrario, muchos otros países de América Latina y el Caribe como Dominica, Perú, Paraguay y Surinam han quedado atrás en este desarrollo, y aunque están en camino, necesitan apoyo institucional para continuar en este proceso.

El problema para combatir dichos problemas tiene su origen, por lo general, en la propia ley de los estados. Solo 8 de los 32 países de la región son parte del Convenio de Budapest, que aboga por la cooperación internacional contra el cibercrimen, y un tercio de estos países no cuenta con una legislación apropiada en su marco legal para los delitos informáticos.

Para los estados parte de dicho convenio, estas directrices pueden servir de gran ayuda para desarrollar las leyes internas y procesales con respecto al ciberdelito, por lo que se está potenciando la adhesión o al menos la observación de las mismas desde organismos como la OEA, con las recomendaciones de unidades especializadas como el Grupo de Trabajo en Delito Cibernético de las REMJA, que aconseja respecto a la reforma de la ley penal respecto al cibercrimen y la evidencia electrónica.

Por otro lado, no ha sido hasta principios de este año que, con la incorporación de Brasil, son 12 países de Latinoamérica y el Caribe los que han establecido una estrategia nacional de ciberseguridad, debido a la falta de talento humano calificado. Aunque cabe destacar los dos países de la región con mayor desarrollo en el ámbito de seguridad cibernética, que son Jamaica y Trinidad y Tobago.

De los problemas mencionados, podemos decir que la falta de estrategia nacional en cuanto a seguridad cibernética expone a estos países a diversos ataques, pero a esto debe añadirse que las empresas que venden los servicios de ciberseguridad y proporcionan apoyo técnico y financiero en la región son mayormente de Israel o Estados Unidos, y están vinculadas a una perspectiva de seguridad y defensa bastante militarizada, lo que supondrá un desafío en los años venideros por la competencia que China está dejando ver en este lado del hemisferio, sobre todo ligada a la tecnología 5G.

Las malas prácticas cibernéticas son una amenaza no solo para la economía de Latinoamérica y el Caribe, sino también para el funcionamiento de la democracia en estos estados, un atentado a los derechos y libertades de la ciudadanía y a los valores de la sociedad. Por ello, es está dejando ver la necesidad de inversión en infraestructura civil y en capacidad militar. Para lograr esto, los estados de la región están dispuestos a cooperar, primeramente, en la unificación de sus marcos legales basándose en los modelos del Convenio de Budapest y las bases de la Unión Europea, cuya perspectiva para afrontar los nuevos retos en el ciberespacio está teniendo gran impacto e influencia en la región.

Además, con la crisis venidera del Covid-19, por lo general los estados de la región están dispuestos a colaborar desarrollando estrategias nacionales propias, coherentes con los valores de las organizaciones de las que son parte, para proteger tanto sus medios actuales como sus tecnologías emergentes (inteligencia artificial, cuántica, computación de alto rendimiento y otros). Las amenazas cibernéticas pretenden ser encaradas desde canales abiertos a la colaboración y el diálogo, ya que Internet no tiene fronteras, y la armonización de los marcos legales es el primer paso para fortalecer esta cooperación no solo regional sino internacional.

La Administración Trump concluye su gestión de modo asertivo en la región y pasa el testigo a la Administración Biden, que parece apostar por el multilateralismo y la cooperación

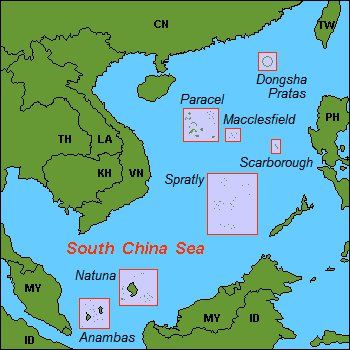

Con el mundo parado a causa del Covid-19, el gigante asiático ha aprovechado para reanudar toda una serie de operaciones con el objetivo de expandir su control sobre los territorios aledaños a su línea de costa. Tales actividades no han dejado indiferente a Estados Unidos, que a pesar de su compleja situación interna ha tomado cartas en el asunto. Con las visitas de Mike Pompeo a lo largo de Asia Pacífico, la potencia norteamericana acrecienta el proceso de contención de Pekín, materializado en una cuádruple alianza entre Estados Unidos, Japón, India y Australia. El nuevo ejecutivo que la Casa Blanca estrenará en enero podrá implicar una renovación del actuar estadounidense que, sin romper con la Administración Trump, recupere el espíritu de la Administración Obama, esto es guiados por una mayor cooperación con los países de Asia Pacífico y apuesta por el diálogo.

![Pista aérea instalada por China en la isla Thitu o Pagasa, la segunda mayor de las Spratly, cuya administración hacía sido reconocida internacionalmente para Filipinas [Eugenio Bito-onon Jr] Pista aérea instalada por China en la isla Thitu o Pagasa, la segunda mayor de las Spratly, cuya administración hacía sido reconocida internacionalmente para Filipinas [Eugenio Bito-onon Jr]](/documents/16800098/0/mar-china-blog.jpg/221fc42a-0d93-e77e-fb3e-4aac0a9ecef0?t=1621874942557&imagePreview=1)

▲ Pista aérea instalada por China en la isla Thitu o Pagasa, la segunda mayor de las Spratly, cuya administración hacía sido reconocida internacionalmente para Filipinas [Eugenio Bito-onon Jr]

ARTÍCULO / Ramón Barba

Durante la pandemia, Pekín ha aprovechado para reanudar sus actuaciones sobre las aguas de Asia Pacífico. A mediados de abril, China procedió a designar terrenos de las islas Spratly, el archipiélago de Paracel y el banco Macclesfield, como nuevos distritos de la ciudad de Sansha, población de la isla china de Hainan. Esa adscripción administrativa causó la subsiguiente protesta de Filipinas y Vietnam, quienes reclaman la soberanía de esos espacios. La actitud de Pekín ha venido aparejada de incursiones y sabotajes a los barcos de la zona. Véase el hundimiento de un pesquero vietnamita, cosa que China desmiente argumentando que había sufrido un accidente y que estaba llevando a cabo actividades ilegales.

Las actuaciones China desde el verano han ido aumentando la inestabilidad en la región mediante ejercicios militares cerca de Taiwán o enfrentamientos con la India debido a sus problemas fronterizos; por otro lado, a la oposición filipina y vietnamita hacia los movimientos chinos cabe aunar la creciente tensión con Australia después de que este país pidiera que se investigara el origen del COVID-19, y el incremento de las tensiones marítimas con Japón. Todo ello ha llevado a una respuesta por parte de Estados Unidos, quien se postula como defensor de la libre navegación en Asia Pacífico justificando así su presencia militar, haciendo énfasis en que la República Popular China no está a favor de ese libre tránsito, ni de la democracia ni del imperio de la ley.

EEUU mueve ficha

Las tensiones entre China y Estados Unidos con relación a la presente disputa han ido in crescendo durante todo el verano, incrementando ambos su presencia militar en la zona (además, Washington ha sancionado a 24 empresas chinas que han ayudado a militarizar el área). Todo ello se ha traducido recientemente en las visitas llevadas a cabo por el secretario de Estado Mike Pompeo a Asia Pacífico a lo largo del mes de octubre. Previamente a esta ronda de visitas, este había hecho declaraciones en septiembre en el Cumbre Virtual de ASEAN instando a los países de la región a limitar sus relaciones con China.

La disputa por tales aguas afecta a Vietnam, Filipinas, Taiwán, Brunéi y Malasia, países que, junto con India y Japón, fueron visitados por Pompeo (entre otros) con el objeto de asegurar un mayor control sobre la actuación de Pekín. Durante su gira, el secretario de Estado norteamericano se reunió con los ministros de Asuntos Exteriores de India, Australia y Japón para unir fuerzas contra el gigante asiático. Seguidamente, Washington firmó en Nueva Delhi un acuerdo militar de intercambio de datos satelitales para rastrear mejor los movimientos chinos en la zona, y realizó una visita de estado a Indonesia. Recordemos que Yakarta se caracterizaba hasta el momento por una creciente amistad con Pekín y un empeoramiento de la relación con Estados Unidos con motivo de un decremento en las ayudas del programa Generalized System of Preferences (GSP). No obstante, durante la visita de Pompeo, ambos países acordaron una mejora de sus relaciones mediante una mayor cooperación en lo regional, contratación militar, inteligencia, entrenamientos conjuntos y seguridad marítima.

Por ende, este movimiento de ficha por parte de Washington ha implicado:

-

La consolidación de una cuádruple alianza entre India, Japón, Australia y Estados Unidos que se ha visto materializada en los ejercicios militares conjuntos en la Bahía de Bengala a principios de noviembre. Cabe recordar que esto se suma a los aliados tradicionales de Washington en la zona (Filipinas, Singapur y Tailandia). Además, queda abierta la posibilidad de una mayor unión con Vietnam.

-

La ampliación de su presencia militar en la zona, aumentando el flujo de material vendido a Taiwán destacando también las visitas de altos funcionarios de Washington a lo largo de julio y los meses siguientes.

-

Retorno del destructor USS Barry a las aguas del Mar del Sur de China con el objetivo de servir como símbolo de oposición a la actuación china, y como defensor de la libertad de navegación, la paz y la estabilidad.

-

Indonesia moverá su Fuerza de Combate Naval (permanentemente asentada en Yakarta) a Natuna, islas fronterizas con el Mar del Sur de China, ricas en recursos naturales y disputadas entre ambos países.

-

ASEAN se posiciona como defensor de la paz y estabilidad y a favor del UNCLOS 1982 (el cual establece el marco legal que rige para el derecho del mar) durante la cumbre celebrada en Vietnam entre el 12-15 de noviembre.

La ratio decidendi detrás de la actuación china

La ratio decidendi detrás de la actuación china

Como primer acercamiento a la ratio decidendi que hay detrás de la actuación china, cabe recordar que desde 2012, aprovechando la inestabilidad regional, el gigante asiático aludía a su derecho histórico sobre los territorios del mar Meridional para justificar sus actuaciones, argumentos desestimados en 2016 por la Corte Permanente de Arbitraje de la Haya. En base al argumento de que, en su día, pescadores chinos frecuentaban la zona, se pretendía justificar la apropiación de más del 80% del territorio, confrontando desde entonces a Pekín con Manila.

Por otro lado Luis Lalinde, en su artículo China y la importancia de dominar el Mar Circundante (2017) da una visión más completa del asunto, aludiendo no solo a motivos históricos, sino también a razones económicas y geopolíticas. En primer lugar, más de la mitad de los hidrocarburos de los que se abastece China transitan por la región de Asia Pacífico, la cual constituye a su vez el principal polo económico mundial. A ello cabe aunarle que Pekín se ha visto muy marcado por el “siglo de las humillaciones”, caracterizado por una falta de control de los chinos sobre su territorio con motivo de invasiones de origen marítimo. Por último, el dominio de los mares junto con el ya alcanzado peso continental, son vitales para la proyección hegemónica de China en un área de cada vez mayor peso económico a nivel mundial. Por ello se establece el denominado “collar de perlas” para la defensa de intereses estratégicos, de seguridad y abastecimiento energético desde el Golfo Pérsico hasta el Mar del sur.

Los argumentos de Lalinde justifican la actuación china de los últimos años, no obstante, Bishop (2020), afirma en el Council on Foreign Relations que la razón detrás de la reciente actitud china se debe a cuestiones de inestabilidad interna en tanto que un pequeño sector de la intelectualidad china se muestra crítico y desconfiado con el liderazgo de Xi. Argumentando que la pandemia ha debilitado la economía y el Gobierno chino por lo que mediante acciones de política exterior debe aparentar fortaleza y vigorosidad. Por último, cabe tener en cuenta la importancia del control de los mares en relación con el proyecto de la Ruta de la Seda. En su vertiente marítima, China está haciendo una gran inversión en puertos del Índico y del Pacífico que no descarta utilizar para fines militares (véase los puertos de: Sri Lanka, Myanmar y Pakistán). De entre los principales opositores a esta alianza encontramos a Estados Unidos, Japón y la India, también en contra de la beligerante actitud china, como se ha visto.

Era Biden: oportunidades en un escenario complicado

La presidencia de Joe Biden va a estar marcada por grandes retos, tanto internos como externos. Estamos ante un Estados Unidos marcado por una crisis sanitaria, con una sociedad cada vez más polarizada y con una economía cuya recuperación, a pesar de las medidas adoptadas, presenta dudas de si será “en V” o “en W”. Además, las relaciones con Iberoamérica y Europa se han ido deteriorando, producto de las medidas tomadas por parte del presidente Trump.

La relación entre China y EEUU ha ido fluctuando en los últimos años. La Administración Obama, consciente de la importancia que la región de Asia Pacífico ha ido alcanzando, aunada a la oportunidad que la Ruta de la Seda presenta para que Pekín expanda su dominio económico y militar, planteó en su segundo mandato su política de Pivot to Asia, comenzando a financiar y dotar de ayudas a países de la región. Durante los años de la Administración Trump, la relación con Pekín se ha deteriorado bastante, lo que pone a Biden en un escenario en el que tendrá que enfrentarse a una guerra comercial, a la carrera tecnológica en la batalla por el 5G, así como a cuestiones de seguridad regional y de derechos humanos.