Breadcrumb

Blogs

Entries with tag drug trafficking .

![Attack in Kashmir linked to groups of Pakistani origin [twitted by @ANI] Attack in Kashmir linked to groups of Pakistani origin [twitted by @ANI]](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-yihadismo-blog.jpg)

▲ Attack in Kashmir linked to groups of Pakistani origin [twitted by @ANI]

ESSAY / Isabel Calderas [Ignacio Lucas as research assistant]

There is a myriad of security concerns regarding external factors when it comes to Pakistan: India, Afghanistan, the Saudi Arabia-Iran split and the United States, to name a few. However, there are also two main concerns that come from within: jihadism and organized crime. They are interconnected but differ in many ways. The latter is frequently overlooked to focus on the former, but both have the capacity of affecting the country, internally and externally, as the effectiveness of dealing with them impacts the perception the international community has of Pakistan. While internally disrupting, these problems also have international reach, as such groups often export their activities, adversely affecting at a global scale. Therefore, international actors put so much pressure on Pakistan to control them. Historically, there has been much scepticism over the government’s ability, or even willingness to solve these risks. We will examine both problems separately, identifying the impact they have on the national and international arena, as well as the government’s approach to dealing with either and the future risks they entail.

1. JIHADISM

Pakistan’s education system has become a central part of the country’s radicalization phenomenon[1], in the materialization of madrassas. These schools, which teach a more puritanical version of Islam than had traditionally been practiced in Pakistan, have been directly linked to the rise of jihadist groups[2]. Saudi Arabia, who has always had very close relations with Pakistan, played a key role in their development, by funding the Ahl-e-Hadith and Deobandi madrassas since the 1970s. The Iranian revolution bolstered the Saudi’s imperative to control Sunnism in Pakistan, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan gave them the vehicle to do so[3]. In these schools, which teach a biased view of the world, students display low tolerance for minorities and are more likely to turn to jihadism.

Saudi and American funding of madrassas during the Soviet occupation helped the Pakistani army’s intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), become more powerful, as they channelled millions of dollars to them, a lot of which went into the madrassas which sent mujahedeen fighters to fight for their cause[4]. The Taliban’s origins can also be traced to these, as the militia was raised mainly from Afghan refugee camps in Pakistan and Saudi-funded madrassas[5].

Madrassas are especially popular in the poorer provinces of the country, where parents send their children to them for several non-religious reasons. First, because the Qur’an is written in Arabic and madrassas teach this language[6]. The dire situation of many families forces millions of Pakistanis to migrate to neighbouring, oil-rich Arabic-speaking countries, from where they send remittances home to help support their families. Secondly, the public-school system in Pakistan is weak, often failing to teach basic reading skills[7], something the madrassas do teach.

Partly in response to the international pressure[8] it has been under to fight terrorism within its territory; Pakistan has tried to reform the madrassas. The government has stated its intention to bring madrassas under the umbrella of the education ministry, financing these schools by allocating cash otherwise destined to fund anti-terrorism security operations[9]. It plans to add subjects like science to the curriculum, to lessen the focus on Islamic teachings. However, this faces several challenges, among which the resistance from the teachers and clerical authorities who run the madrassas outstands[10].

Before moving on to the prominent radical groups in Pakistan, we would like to make a brief summary on a different cause of radicalization: the unintended effect of the drone strategy adopted by the United States.

The United States has increasingly chosen to target its radical enemies in Pakistan through the use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), which can be highly effective in neutralizing objectives, but also pose a series of risks, like the killing of innocent civilians that are in the neighbouring area. This American strategy, which Pakistan has publicly criticized, has fomented anti-American sentiment among the Pakistanis, at a ratio on average of every person killed resulting in the radicalization of several more people[11]. The growing unpopularity of drone strikes has further weakened relations between both governments, but shows no signs of changing in the future, if recent attacks carried by the U.S. are any indication. Pakistan’s efforts to de-radicalize its population will continue to be undermined by the U.S. drone strikes[12].

Pakistan’s anti-terrorism strategy is linked to its geostrategic and regional interests, especially dealing with its eastern and western neighbours[13]. There are many radical groups operating within their territory, and the government’s strategy towards them shifts depending on their goal[14]. Groups like the Afghan Taliban, who target foreign invasions in their own country, and Al Qaeda, whose jihad against the West is on a global scale, have been allowed to use Pakistani territory to coordinate operations and take refuge. Their strategy is quite different for Pakistani Taliban group, Tehrik-e-Taliban (TTP) who, despite being allied with the Afghan Taliban, has a different goal: to oust the Pakistani government and impose Sharia law[15]. Most of the military’s campaigns aimed at cracking down on radicals have been targeted at weakening groups affiliated with TTP. Lastly, there are those groups with whom some branches of the Pakistani government directly collaborate with.

Pakistan has been known to use jihadi organizations to advance its security objectives through proxy conflicts. Pakistan’s policy of waging war through terrorist groups is planned, coordinated, and conducted by the Pakistani Army, specifically the ISI[16] who, as previously mentioned, plays a vital role in running the State.

Although this has been a longstanding cause of tension between the Pakistani and the American governments, the U.S. has made no progress in persuading or compelling the Pakistani military to sever ties with the radical groups[17], even though the Pakistani government has stated that it has, over the past year, ‘fought and eradicated the menace of terrorism from its soil’ by carrying out arrests, seizing property and freezing bank accounts of groups proscribed by the United States and the United Nations[18]. Their actions have been enough to keep them off the FATF’s blacklist for financing terrorism and money laundering[19], which would prevent them from getting financing, but concerns remain about ISI’s involvement with radical groups, the future of the relations between them, the overall activity of these groups from within Pakistani territory, and the risk of a future attack to its neighbours.

We will use two of Pakistan’s main proxy groups, Lashkar-e-Tayyiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad, to analyse the feasibility of an attack in the near future.

1.1. Lashkar-e-Tayyiba (LeT)

Created to support the resistance against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, LeT now focuses on the insurgencies in Afghanistan and Kashmir, the highest priorities for the Pakistani military’s foreign policy. The Ahl-e-Hadith group is led by its founder, Hafiz Saeed. Its headquarters are in Punjab. Unlike its counterparts, it is a well-organized, unified, and hierarchical organization, which has become highly institutionalized in the last thirty years. As a result, it has not suffered any major losses or any fractures since its inception[20].

Since the Mumbai attacks in 2008 (which also involved ISI), for which LeT were responsible, its close relationship with the military has defined the group’s operations, most noticeably by restraining their actions in India, which reflects both the Pakistani military’s desire to avoid international pressure and conflict with their neighbour and the group’s capability to contain its members. The group has calibrated its activities, although it possesses the capability to expand its violence. Its outlets for violence have been Afghanistan and Kashmir, which align with the Pakistani military’s agenda: to bring Afghanistan under Pakistan’s sphere of influence while keeping India off-balance in Kashmir[21]. The recent U.S.-Taliban deal in Afghanistan and militarization of Kashmir by India may change this. LeT has benefitted handsomely for its loyalty, receiving unparalleled protection, patronage, and privilege from the military. However, after twelve years of restraint, Lashkar undoubtedly faces pressures from within its ranks to strike against India again, especially now that Narendra Modi is prime minister.

1.2. Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM)

The Deobandi organization, led by its founder Masood Azhar, has had close bonds with Al-Qaeda and the Taliban since they came into light in 2000. With the commencement of the war on terror in Afghanistan, JeM reciprocated by launching an attack on the Indian Parliament on December 2001, in cooperation with LeT. However, it ignored the Pakistani military’s will in 2019 when it launched the Pulwama attack, after which the government of Pakistan launched a countrywide crackdown on them, taking leaders and members into preventive custody[22].

1.3. Risk assessment

Although it has gone rogue before, Jaish-e-Muhammad has been weakened by the recent government’s crackdown. What remains of the group, consolidated under Masood Azhar, has repaired ties with the military. Although JeM has demonstrated it still possesses formidable capability in Indian Kashmir, Lashkar-e-Tayyiba represents the main concern for an attack on India in the near future.

Lashkar has been both the most reliable and loyal of all the proxy groups and has also proven it does not take major action without prior approval from the ISI, which could become a problem. Pakistan has adopted a policy of maintaining plausible deniability for any attacks in order to avoid international pressure after 9/11, thus LeT’s close ties with the military make it more likely that its actions will provoke a war between the two countries.

The United States has tried for several years to get Pakistan to stop using proxies. There are several scenarios in which Lashkar would break from the Pakistani state (or vice versa), but they are farfetched and beyond foreign influence: a) a change in Pakistan’s security calculus, b) a resolution on Kashmir, c) a shift in Lashkar’s responsiveness and d) a major Lashkar attack in the West[23].

a) A change in Pakistan’s security calculus is the least likely, as the India-centric understanding of Pakistan’s interests and circumstances is deeply embedded in the psyche of the security establishment[24].

b) A resolution on Kashmir would trouble Lashkar, who seeks full unification of all Kashmir with Pakistan, which would not be the outcome of a negotiated resolution. More so, Modi’s recent decision regarding article 370 puts this possibility even further into the future.

c) A shift in Lashkar responsiveness would be caused by the internal pressures to perform another attack, after more than a decade of abiding by the security establishment’s will. If perceived as too powerful of insufficiently responsive, ISI would most likely seek to dismantle the group, as they did with Jaish-e-Muhammad, by focusing on the rogue elements and leaving Lashkar smaller but more responsive. This presents a threat, as the group would not allow itself to be simply dismantled but would probably resist to the point of becoming hostile[25].

d) The last option, a major Lashkar attack in the West, is also unlikely, as the group has not undertaken any major attack without perceived greenlight from ISI.

This does not mean that an attack from LeT can be ruled out. ISI could allow the group to carry out an attack if, in the absence of a better reason, it feels that the pressure from within the group will start causing dissent and fractures, just like it happened in 2008. It is in ISI’s best interest that Lashkar remains a strong, united ally. Knowing this, it is important to note that a large-scale attack in India by Lashkar is arguably the most likely trigger to a full-blown conflict between the two nations. Even a smaller-scale attack has the potential of provoking India, especially under Modi.

If such an attack where to happen, India would not be expected to display a weak-kneed gesture, as PM Modi’s policy is that of a tough and powerful approach in defence vis-à-vis both Pakistan and China. This has already been made evident by its retaliation for the Fidayeen attack at Uri brigade headquarters by Jaish-e-Muhammad in 2016[26]. It has now become evident that if Pakistan continues to harbour terrorist groups against India as its strategic assets, there will be no military restraint by India as long as Modi is in power, who will respond with massive retaliation. In its fragile economic condition, Pakistan will not be able to sustain a long-drawn war effort[27].

On the other hand, Afghanistan, which has been the other focus of Pakistan’s proxy groups, is now undergoing a process which could result in a major organizational shift. The Taliban insurgent movement has been able survive this long due to the sanctuary and support provided by Pakistan[28]. Furthermore, Lashkar-e-Tayyiba’s participation in the Afghan insurgency furthered the Pakistani military’s goal of having a friendly, anti-India partner on its western border[29]. The development and outcome of the intra-Afghan talks will determine the continued use of proxies in the country. However, we can realistically assume that, at least in the near future, radical groups will maintain some degree of activity in Afghanistan.

It is highly unlikely that the Pakistani intelligence establishment will stop engaging with radical groups, as it sees in them a very useful strategic tool for achieving its security goals. However, Pakistan’s plausible deniability approach will come into question, as its close ties with Lashkar-e-Tayyiba make it increasingly hard for it to deny involvement in its acts with any credibility. Regarding India, any kind of offensive from this group could result in a large-scale conflict. This is precisely the most likely scenario to occur, as Modi’s history with Lashkar-e-Tayyiba and their twelve-year-long “hiatus” from impactful attacks could propel the organization to take action that will impact the whole region.

2. DRUG TRAFFICKING

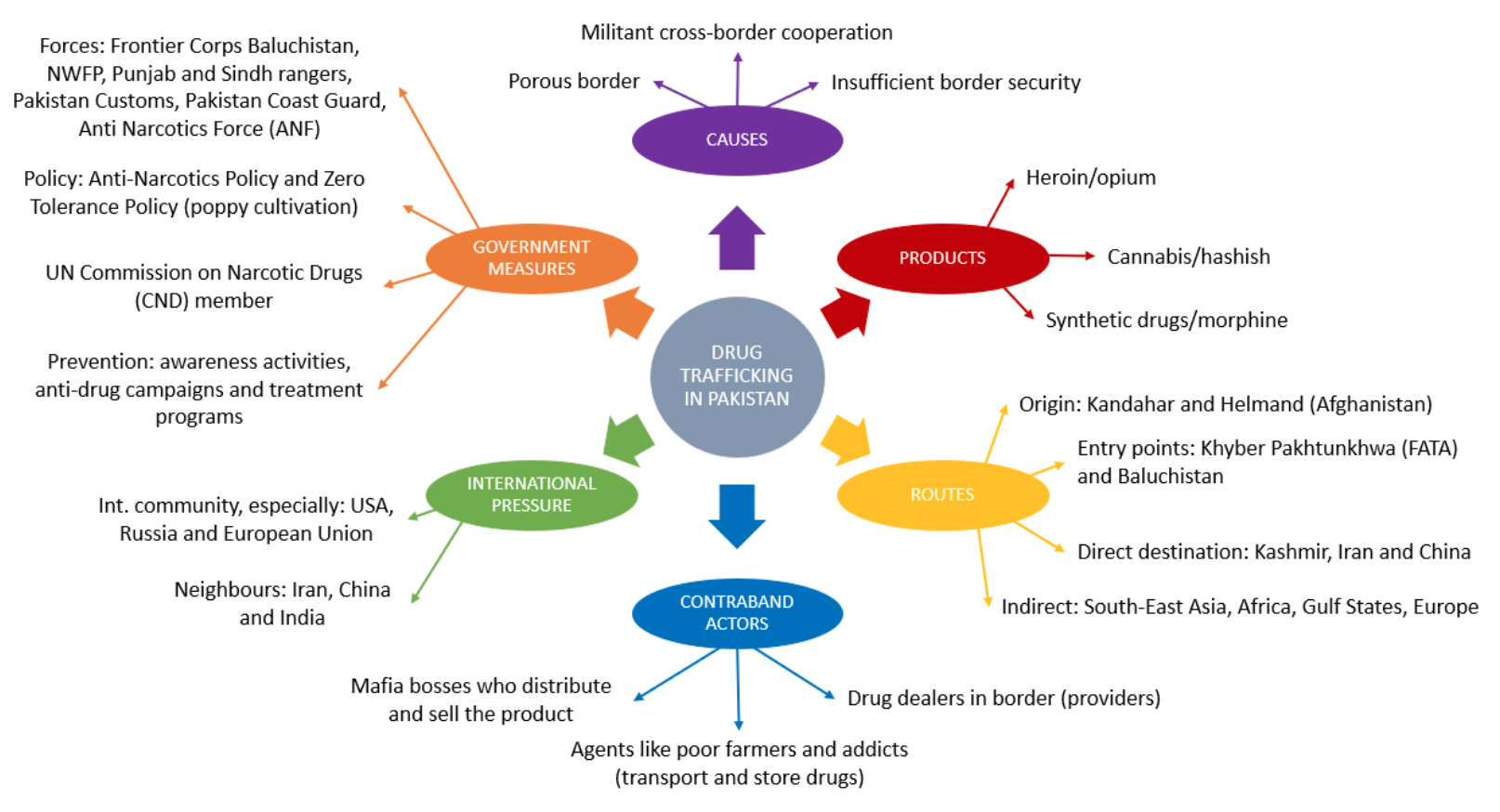

Drug trafficking constitutes an important problem for Pakistan. It originates in Afghanistan, from where thousands of tonnes are smuggled out every year, using Pakistan as a passageway to provide the world with heroin and opioids[30]. The following concept map has been elaborated with information from diverse sources[31] to present the different aspects of the problem aimed to better comprehend the complex situation.

Afghanistan, one of the world’s largest heroin producers, has supplied up to 60% and 80% of the U.S. and European markets, respectively. The landlocked country takes advantage of its blurred border line, and the remoteness and inaccessibility of the sparsely populated bordering regions with Pakistan, using it as a conduct to send its drugs globally. The Pakistani government is under a lot of pressure from the international community to fight and minimize drug trafficking from its territory.

Pakistan feels a special kind of pressure from the European Union, as its GSP+ status could be affected if it does not control this problem. The GSP+ is dependent on the implementation of 27 international conventions related to human rights, labour rights, protection of the environment and good governance, including the UN Convention on Fighting Illegal Drugs[32]. Pakistan was granted GSP+ status in 2014 and has shown commitment to maintaining ratifications and meeting reporting obligations to the UN Treaty bodies[33]. However, one of the aspects of the scheme is its “temporary withdrawal and safeguard” measure, which means the preferences can be immediately withdrawn if the country is unable to control drug trafficking effectively[34]. This has not been the case, and the EU has recognized Pakistan’s efforts in the fight on drugs; the UN has also removed it from the list of cannabis resin production countries[35]. Anti-corruption frameworks have been strengthened, along with legislation review and awareness building, but they have been advised that better coordination between law enforcement agencies is needed[36].

The GSP+ status is very important to Pakistan, as the European Union is their first trade partner, absorbing over a third of their total exports in 2018, followed by the U.S., China and Afghanistan[37]. The Union can use this as leverage to obtain concessions from Pakistan. However, the approach they have taken so far has been of collaboration in many areas, including transnational organized crime, money laundering and counter-narcotics[38]. In this sense, the EU ambassador to Pakistan recently stated that the new Strategic Engagement Plan of 2019 would “further boost their relations in diverse fields”[39].

Even with combined efforts, erradicating the drug trafficking problem in Pakistan has proven to be very difficult. This is because production of the drug is not done in its territory, and even if border patrols are strengthened, it will be very hard to stop drugs from coming in from its neighbour if the Afghan government doesn’t take appropriate measures themselves.

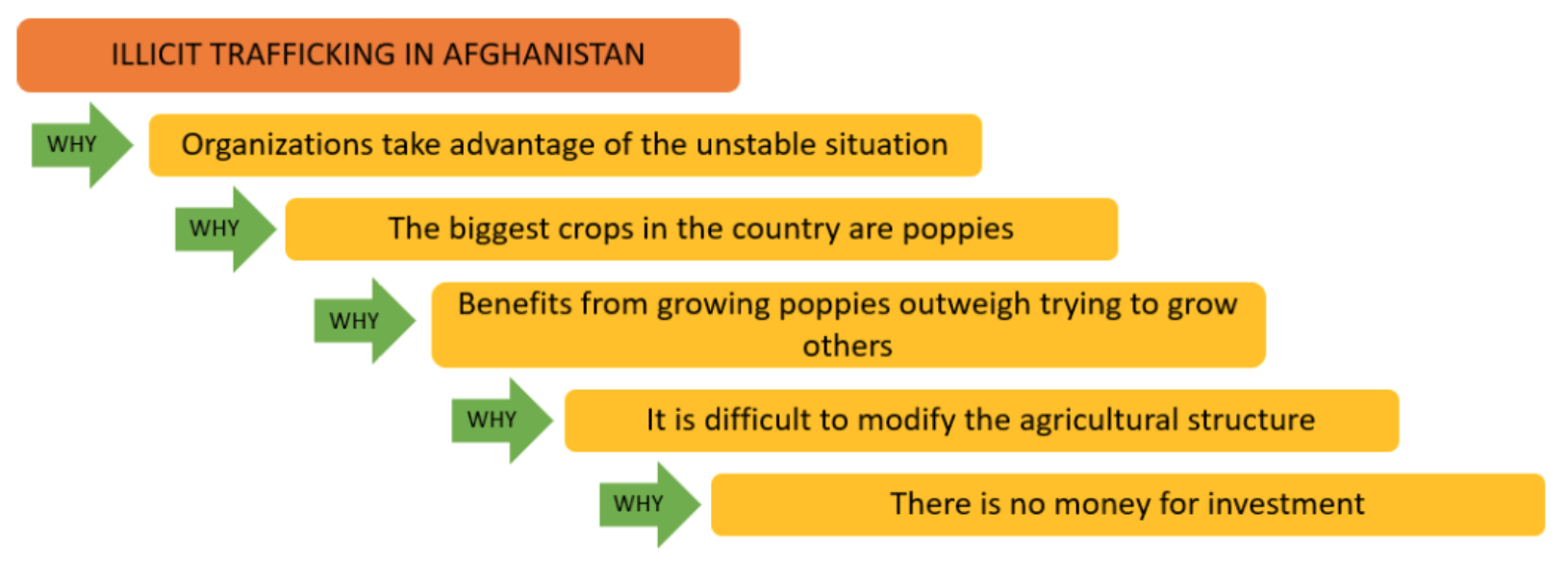

A “5 whys” exercise has led us to understand that the root cause of the problem is the fact that most farmers in Afghanistan are too poor to turn to different crops. A nearly two decade war has ravaged the country’s land, leaving opium crops, which are cheaper and easier to maintain, as the only option for most farmers in this agrarian nation. A substantial investment in the country’s agriculture to produce more economic options would be needed if any serious advance is expected to be made in stopping illegal drug trafficking. These investments will have to be a joint effort of the international community, and funding for the government will also be necessary, if stability is to be reached. Unless this is done, opium will likely remain entangled in the rural economy, the Taliban insurgency, and the government corruption whose sum is the Afghan conundrum[40]. And as long as this does not happen, it is highly unlikely that Pakistan will be able to make any substantial progress in its effort to fight illicit drugs.

[1] Khurshid Khan and Afifa Kiran, “Emerging Tendencies of Radicalization in Pakistan,” Strategic Studies, vol. 32, 2012.

[2] Hassan N. Gardezi, “Pakistan: The Power of Intelligence Agencies,” South Asia Citizenz Web, 2011, http://www.sacw.net/article2191.html.

[3] Madiha Afzal, “Saudi Arabia’s Hold on Pakistan,” 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/research/saudi-arabias-hold-on-pakistan/.

[4] Gardezi, “Pakistan: The Power of Intelligence Agencies.”

[5] Ibid.

[6] Myriam Renaud, “Pakistan’s Plan to Reform Madrasas Ignores Why Parents Enrol Children in First Place,” The Globe Post, May 20, 2019, https://theglobepost.com/2019/05/20/pakistan-madrasas-reform/.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Drazen Jorgic and Asif Shahzad, “Pakistan Begins Crackdown on Mlitant Groups amid Global Pressure,” Reuters, March 5, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-kashmir-pakistan-un/pakistan-begins-crackdown-on-militant-groups-amid-global-pressure-idUSKCN1QM0XD.

[9] Saad Sayeed, “Pakistan Plans to Bring 20,000 Madrasas under Government Control,” Reuters, April 29, 2019.

[10] Renaud, “Pakistan’s Plan to Reform Madrasas Ignores Why Parents Enrol Children in First Place.”

[11] International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clininc (Stanford Law Review) and Global Justice Clinic (NYE School of Law), “Living Under Drones: Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians From US Drone Practices in Pakistan,” 2012, https://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/default/files/publication/313671/doc/slspublic/Stanford_NYU_LIVING_UNDER_DRONES.pdf.

[12] Saba Noor, “Radicalization to De-Radicalization: The Case of Pakistan,” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 5, no. 8 (2013): 16–19.

[13] Muhammad Iqbal Roy and Abdul Rehman, “Pakistan’s Counter Terrorism Strategy (2001-2019): Evolution, Paradigms, Prospects and Challenges,” Journal of Politics and International Studies 5, no. July-December (2019): 1–13.

[14] Madiha Afzal, “A Country of Radicals? Not Quite,” in Pakistan Under Siege: Extremism, Society, and the State (Brookings Institution Press, 2018), 208, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/chapter-one_-pakistan-under-siege.pdf.

[15] Ibid.

[16] John Crisafulli et al., “Recommendations for Success in Afghanistan,” 2019, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep20107.7.

[17] Tricia Bacon, “The Evolution of Pakistan’s Lashkar-e-Tayyiba,” Orbis, no. Winter (2019): 27–43.

[18] Susannah George and Shaiq Hussain, “Pakistan Hopes Its Steps to Fight Terrorism Will Keep It off a Global Blacklist,” The Washington Post, February 21, 2020.

[19] Husain Haqqani, “FAFT’s Grey List Suits Pakistan’s Jihadi Ambitions. It Only Worries Entering the Black List,” Hudson Institute, February 28, 2020.

[20] Bacon, “The Evolution of Pakistan’s Lashkar-e-Tayyiba.”

[21] Ibid.

[22] Farhan Zahid, “Profile of Jaish-e-Muhammad and Leader Masood Azhar,” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 11, no. 4 (2019): 1–5, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26631531.

[23] Tricia Bacon, “Preventing the Next Lashkar-e-Tayyiba Attack,” The Washington Quarterly 42, no. 1 (2019): 53–70.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Abhinav Pandya, “The Future of Indo-Pak Relations after the Pulwama Attack,” Perspectives on Terrorism 13, no. 2 (2019): 65–68, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26626866.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Crisafulli et al., “Recommendations for Success in Afghanistan.”

[29] Bacon, “The Evolution of Pakistan’s Lashkar-e-Tayyiba.”

[30] Alfred W McCoy, “How the Heroin Trade Explains the US-UK Failure in Afghanistan,” The Guardian, January 9, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/jan/09/how-the-heroin-trade-explains-the-us-uk-failure-in-afghanistan.

[31] Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray and Dr. Shanthie Mariet D Souza, “The Afghanistan-India Drug Trail - Analysis,” Eurasia Review, August , https://www.eurasiareview.com/02082019-the-afghanistan-india-drug-trail-analysis/; Mehmood Hassan Khan, “Kashmir and Power Politics,” Defence Journal 23, no. 2 (2019); McCoy, “How the Heroin Trade Explains the US-UK Failure in Afghanistan”; Pakistan United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Country Office, “Illicit Drug Trends in Pakistan,” 2008, https://www.unodc.org/documents/regional/central-asia/Illicit Drug Trends Report_Pakistan_rev1.pdf; “Country Profile - Pakistan,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2020, https://www.unodc.org/pakistan/en/country-profile.html.

[32] European Commission, “Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP),” 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/development/generalised-scheme-of-preferences/.

[33] High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, “The EU Special Incentive Arrangement for Sustainable Development and Good Governance ('GSP+’) Assessment of Pakistan Covering the Period 2018-2019” (Brussels, 2020).

[34] Dr. Zobi Fatima, “A Brief Overview of GSP+ for Pakistan,” Pakistan Journal of European Studies 34, no. 2 (2018), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333641020_A_BRIEF_OVERVIEW_OF_GSP_FOR_PAKISTAN.

[35] High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, “The EU Special Incentive Arrangement for Sustainable Development and Good Governance ('GSP+’) Assessment of Pakistan Covering the Period 2018-2019.”

[36] Fatima, “A Brief Overview of GSP+ for Pakistan.”

[37] UN Comtrade Analytics, “Trade Dashboard,” accessed March 27, 2020, https://comtrade.un.org/labs/data-explorer/.

[38] European External Action Services, “EU-Pakistan Five Year Engagement Plan” (European Union, 2017), https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eu-pakistan_five-year_engagement_plan.pdf; European Union External Services, “EU-Pakistan Strategic Engagement Plan 2019” (European Union, 2019), https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eu-pakistan_strategic_engagement_plan.pdf.

[39] “EU Ready to Help Pakistan in Expanding Its Reports: Androulla,” Business Recorder, October 23, 2019.

[40] McCoy, “How the Heroin Trade Explains the US-UK Failure in Afghanistan.”