Breadcrumb

Blogs

Entries with Categorías Global Affairs Orden mundial, diplomacia y gobernanza .

![Kim Jung-un and Moon Jae-in met for the first time in April, 2018 [South Korea Gov.] Kim Jung-un and Moon Jae-in met for the first time in April, 2018 [South Korea Gov.]](/documents/10174/16849987/soft-power-corea-blog.jpg)

▲Kim Jung-un and Moon Jae-in met for the first time in April, 2018 [South Korea Gov.]

ANALYSIS / Kanghun Ji

North Korea has always utilized its nuclear power as a leverage for negotiation in world politics. Nuclear weapons, asymmetric power, are the last measure for North Korea which lacks absolute military and economic power. Although North Korea lags behind the United States and South Korea in military/economic power, its possession of nuclear weapons renders it a significant threat to other countries. Recently, however, they have continued to develop their nuclear power in disregard of international regulations. In other words, they have not used nuclear issue as a leverage for negotiation to induce economic support. They have rather concentrated on completing nuclear development, not considering persuasion from peripheral countries. This attitude can be attributed to the fact that the development of their nuclear power is almost complete. Many experts say that North Korea judges the recognition of their nation with nuclear power to be a more powerful negotiation tool (Korea times, 2016).

In this situation, South Korea has been trying many different kinds of strategies to resolve the nuclear crisis because security is their main goal: United States-South Korea joint military exercises and United Nations sanctions against North Korea are some of those strategies. Despite these oppressive methods using hard power, North Korea has refused to participate in negotiations.

Most recently, however, North Korea has discarded its previous stance for a more peaceful and amicable position following the PyeongChang Olympics. Discussions about nuclear power are proceeding and the nation has even declared that they will stop developing nuclear power.

Diverse causes such as international relations or economic needs influence their transition. This essay would argue that the soft power strategies of South Korea are substantially influencing North Korea. Therefore, an analysis of South Korea’s soft power strategies is necessary in order to figure out the successful way to resolve the nuclear crisis.

Importance of soft-power strategies in policies against North Korea

North Korea has justified its dictatorship through the development of its ‘Juche’ ideology which is very unique. This ideology is established on the theory of ‘rule by class’ which stems from Marxism-Leninism. In addition, the regime has combined it with Confucianism that portrays a dictator as a father of family (Jung Seong Jang, 1999). Through this justification, a dictator is located at the top of class, which would complete the communist ideal. People are taught this ideology thoroughly and anyone who violates the ideology is punished. To open up this society which has formerly been ideologically closed, their ideology should be undermined by other attractive ideology, culture, and symbol.

However, North Korea has effectively blocked it. For example, recently, many people in North Korea have covertly shared TV shows and music from South Korea. People who are caught enjoying this culture are severely punished by the government. In these types of societies, oppression through hard power strategies doesn’t affect making any kind of change in internal society. It rather could be used to enhance internal solidarity because the potential offenders such as United States or South Korea are postulated as certain enemies to North Korea, which requires internal solidarity to people. North Korea has actually depicted capitalism, United States and South Korea as the main enemies in media. It intends to induce loyalty from people.

As a result, the regime have developed nuclear weapons successfully under strong censorship. Nuclear power is the main key to maintain the dictatorship. The declaration of ‘Nuclear-Economy parallel development’ from the start of Kim Jung-Eun’s government implies that the regime would ensure nuclear weapon as a measure to maintain its system. In this situation, sending the message that its system can coordinately survive alongside South Korea in world politics is important. Not only oppressive strategies but also appropriate strategies which attract North Korea to negotiate are needed.

Analysis of South Korea Soft Power Strategies

In this analysis, I will employ a different concept of soft power compared from the one given by Joseph Nye. Nye’s original concept of soft power focuses on types of behavior. In terms of his concept, co-optive power such as attraction and persuasion also constitutes soft power regardless of the type of resource (Joseph Nye, 2013). However, the concept of soft power I will use focuses on what types of resources users use regardless of the type of behaviors. Therefore, any kinds of power exerted by only soft resources such as images, diplomacy, agenda-setting and so on could be soft power. It is a resource-based concept compared to Nye’s concept which is behavior based (Geun Lee, 2011).

I use this concept because using hard resources such as military power and economic regulation to resolve the nuclear problem in North Korea has been ineffective so far. Therefore, using the concept of soft power which is based on soft resources makes it possible to analyze different kinds of soft power and find ways to improve it.

According to the thesis by Geun Lee (2011: p.9) who used the concept I mentioned above, there are 4 categories of Soft Power. I will use these categories to analyze the soft power strategies of South Korea.

|

1. Application of soft resources – Fear – Coercive power (or resistance) |

|

2. Application of soft resources – Attractiveness, Safety, Comfort, Respect – Co-optive power |

|

3. Application of soft resources (theories, interpretative frameworks) – New ways of thinking and calculating – Co-optive power |

|

4. Socialization of the co-optive power in the recipients – Long term soft power in the form of “social habit” |

1. Oppression through diplomacy: Two-track diplomacy

South Korea takes advantage of soft power strategies that request a global mutual-assistance system in order to oppress North Korea. Based on diplomatic capabilities, South Korea has tried to make it clear that all countries in world politics are demanding a solution to the North Korean nuclear crisis. Through these strategies, it wants to provoke fear in North Korea that it would be impossible to restore its relationship with the world. These strategies have been influential because they are harmonized with United Nations’ Security Council resolutions. Especially, the two-track diplomacy conducted by the president Moon-jae-in in the United Nations general assembly in 2017 is evaluated to be successful. He gave North Korea two options in order to attract them to negotiate (The fact, 2017). The president Moon-jae-in stressed the importance of cooperation about nuclear crisis among countries in his address to the general assembly. Moreover, he discussed the issue with the presidents of United States and Japan and pushed for a firm stance against the North Korea nuclear problem. However, at the same time, he declared that South Korea is ready for peaceful negotiation and discussion if North Korea wish to negotiate and stop developing its nuclear power. By offering two options, South Korea not only aimed to incite fear in North Korea but also left room for North Korea to appear at the negotiation tables.

Strategies using diplomatic capabilities are valuable because they can induce coercive power through soft resources. However, it would be difficult to judge the effectiveness if North Korea didn’t show any reaction to these strategies. Moreover, the cooperation with Russia and China is very important to persuade North Korea because they are maintaining amicable relationships with North Korea against United States and Japan. In the situation that North Korea has aimed to complete development of nuclear weapons for negotiation, diplomatic oppression is not effective itself for making change.

|

Joint statement by the leaders of North and South Korea, in April 2018 [South Korea Gov.] |

2. Sports and culture: Peaceful gesture

The attempt to converse through sports and culture is one of the soft power strategies used by South Korea in order to solve the nuclear crisis. This strategy intends to obtain North Korea’s cooperation in non-political areas which could then spread to political negotiations. As a result of this strategy, South Korea and North Korea formed a unified team during the last Olympics and Asian games (Yonhapnews, 2018). However, for it to be a success, their cooperation should not be limited to the non-political area, but instead should lead to a constructive conversation in politics. In these terms, South Korea’s peaceful gesture in the Pyeong-Chang winter Olympic is seen to have brought about positive change. Before the Olympics, many politicians and experts were skeptical to the gesture because North Korea conducted the 6th nuclear test in 2017, ignoring South Korea’s message (Korea times, 2018). In extension of the two-track diplomacy strategy, nevertheless, the South Korea government has continually shown a desire to cooperate with North Korea. These strategies focus on cooperation only in soft power domains such as sports, culture, and music rather than domains that expose serious political intension.

In the United Nations general assembly which adopted a truce for the Pyeong-Chang Olympics, gold medalist Kim-yun-a required North Korea to participate in Olympics on her address (Chungang, 2017). Moreover, in the event for praying successful Olympics, the president Moon-jae-in sent another peaceful gesture mentioning that South Korea would wait for the participation of North Korea until the beginning of Olympics (Voakorea, 2017). This strategy ended up having successfully attracted North Korea. As a result, they composed a unified ice hockey team and diplomats were dispatched from North Korea during the Olympics to watch the game with South Korean government officials. And then, they exchanged cultural performances in Pyeong-Chang and Pyeong-yang. Finally, the efforts led to the summit meeting between South-North Korea, and North Korea even declared that it would stop developing nuclear power and establish cooperation with South Korea.

It is too early to judge whether North Korea will stop developing their nuclear influence. However, it is a success in the sense that South Korea has attracted North Korea into conversations. Especially, South Korea has effectively taken advantage of the situation that all countries in international relations pay attention to the nuclear crisis of North Korea. They continuously pull North Korea into the center of world politics and leave North Korea without alternative option. Continuous agenda-setting and issue making has finally attracted North Korea.

3. Agenda-setting and framing

It is important to continuously set agendas about issues which are related to North Korea’s violations concerning the nuclear crisis and human rights. Although North Korea is isolated from world politics, it can’t operate its system if it refuses to cooperate or trade with other countries. As a result, it do not want to be in constant conflict with world politics. Therefore, the focal point of agenda-setting South Korea should impress is the negative effects of nuclear policies and dictatorship of North Korea. Moreover, South Korea should recognize that the goal of developing nuclear influence of North Korea is not to declare war but to ensure protection for their political system. South Korea needs to continuously stress that political system of North Korea would be insured after nuclear dismantlement. These strategies change thoughts of North Korea and induce it to participate in negotiations.

However, South Korea has not been effectively employing this strategy. Agenda-setting which might arouse direct conflict with North Korea could aggravate their relationship. This explains its unwillingness to resort to this strategy. On the other hand, the United States show effective agenda-setting which relates to the nuclear crisis mentioning Iran as a positive example of a successful negotiation.

South Korea needs to set and frame the agenda about similar issues closely related to North Korea. For example, the rebellion against the dictatorship in Syria and the resulting death of the dictator in Yemen which stem from tyrannical politics could be a negative precedent. Also, the agreement with Iran that acquired economic support by abandoning nuclear development could be a positive precedent. Through this agenda setting, South Korea should change the thought of North Korea about their nuclear policies. If this strategy succeeds, North Korea will obtain a new interpretative framework, which could lead them to negotiate.

4. Competition of system: North Korea defector and Korean wave

The last type of soft power strategy is a fundamental solution to provoke change. While the strategies I mentioned above directly targets the North Korea government, this strategy mainly targets the people and the society of North Korea. Promoting economic, cultural superiority could influence the North Korean people and then it could lead to movements which would require a transition from the current society. There are many different kinds of way to conduct this strategy and it is abstract in that we can’t measure how much it could influence society. However, it could also be a strategy which North Korea fears the most in the sense that it could provoke change from the bottom of the society. In addition to this, it could arouse fundamental doubt about the ‘Juche’ ideology or nuclear development which is maintained by an exploitative system.

One of these strategies is the policy concerning defectors. South Korea has been implementing policies which accept defectors and help them adjust to the South Korea society. These defectors get a chance to be independent through re-socialization. And then, some of them carry out activities which denounce the horrible reality of the internal society of North Korea. If their voice became influential in world politics, it could become a greater threat to the North Korea system. In 2012, some defectors testified against the internal violation of human rights in UNCHR to gain attention from the world (Newsis, 2016).

In addition, recently, Korean dramas and music are covertly shared within the North Korea society (Daily NK, 2018). It could also provoke a social movement to call for change. Because the contents reflect a much higher standard of living, it triggers curiosity and admiration from North Korean people. These strategies lead society of North Korea to socialize with the co-optive power in the recipients. Ultimately, long term soft power could threaten North Korea itself.

Limits and conclusion

This essay has analyzed the strategies South Korea has used in order to resolve the North Korean nuclear crisis. South Korea threatens North Korea utilizing consensus among countries. Strategies its government has shown such as the speech of the president Moon-jae-in in the United Nations general assembly, the winter Olympics which reflected a desire for peace and the two-track diplomacy are totally different from the consistently conservative policies that the previous governments showed during the last ten years. In addition, the declaration of the Trump’s administration that they would continuously pressure North Korea about nuclear issues offered the opportunity to react to North Korea’s nuclear policies. In this process, active joint response among South Korea, United States and Japan is also necessary.

However, it is true that there are some drawbacks. In order for North Korea to eventually accept nuclear disarmament, South Korea absolutely needs to cooperate with Russia and China which are not only in a good relationship with North Korea but also in a comparatively competitive relationship with the United States and Japan. If South Korea will succeed in gaining their support, the process of reaching an agreement concerning nuclear issues would be much easier.

Eventually, in contrast with the hard power strategies with hard resources, soft power strategies with soft resources can only be effective when South Korea offers the second attractive option. The options are diverse. The main point is that North Korea should recognize the positive effects of abandoning nuclear.

Also, South Korea should recognize that the effect of soft power strategies is maximized when it coexists with economic / military oppression through hard power. In other words, South Korea must take into account Joseph Nye’s smart power to solve the nuclear crisis.

In this process, the most important thing is to persuade North Korea by offering an attractive choice. The reason why North Korea desires to have a summit meeting with South Korea and the United States is because they judge that the choice would be more profitable. Therefore, the South Korean government needs to reflect upon what objectives North Korea has when they accept to negotiate. For example, China’s economic opening is an example of a good precedent that North Korea could follow. South Korea needs to give North Korea a blue print such as the example of China and lead the agreement about the nuclear problem.

Lastly, it is difficult to apprehend the effectiveness of soft power strategies with soft resources, mentioned by Geun Lee, in the sense that the data and the figures about this strategy are not easy to measure in contrast with hard power strategies. Also, many causes exist concerning change of North Korea. Therefore, further research needs to establish a system to get concrete and scientific data in order to apprehend the complex causes and effects of this strategy such as that stem from smart power strategies.

References

Geun Lee (2009) A theory of soft power and Korea's soft power strategy, Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, 21:2, 205-218, DOI: 10.1080/10163270902913962

Joseph S. Nye. JR. (2013) HARD, SOFT, AND SMART POWER. In: Andrew F. Cooper, Jorge Heine, and Ramesh Thakur(eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy, pp.559-574

Jung Seong Jang. (1999) Theoretical Structure and Characteristics of the Juche Ideology. 북한연구학회보, 3:2, 251-273

Chungang ilbo, (2017) 김연아, 평화올림픽 위해 UN에서 4분 영어연설 [Online] Available.

DAILY NK. (2018) 어쩔 수 없이 인도영화를 처벌강화에 南드라마 시청 주춤 [Online] Available.

Korea Times. (2018) 북한, 평창올림픽 참가 놓고 정치권 장외설전 가열 [Online] Available.

Korean Times. (2016) 왜 북한은 핵개발을 멈추지 않는가? [Online] Available.

Newsis. (2016) 탈북자들, 유엔 인권위에서 강제낙태와 고문 등 증언 [Online] Available.

The Fact. (2017) 文대통령’데뷔전’ UN본부 입성… ‘북핵 파문’ NYPD ’긴장’ [Online] Available.

Voakorea. (2017) 문재인 한국 대통령 “북한 평창올림픽 참가 끝까지 기다릴 것” [Online] Available.

Yonhapnews. (2018) 27년 만에 ‘남북 단일팀’ 출범 임박… 올림픽은 사상 최초 [Online] Available.

WORKING PAPER / N. Moreno, A. Puigrefagut, I. Yárnoz

ABSTRACT

The fundamental characteristic of the external action of the European Union (EU) in recent years has been the use of the so-called soft power. This soft power has made the Union a key actor for the development of a large part of the world’s regions. The last decades the EU has participated in a considerable amount of projects in the economic, cultural and political fields in order to fulfil the article 2 of its founding Treaty and thus promote their values and interests and contribute to peace, security and sustainable development of the globe through solidarity and respect for all peoples. Nevertheless, EU’s interventions in different regions of the world have not been free of objections that have placed in the spotlight a possible direct attack by the Union to the external States’ national sovereignties, thus creating a principle of neo-colonialism by the EU.

Download the document [pdf. 548K]

Download the document [pdf. 548K]

![Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman and President Donald Trump during a meeting in Washington in 2017 [White House] Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman and President Donald Trump during a meeting in Washington in 2017 [White House]](/documents/10174/16849987/women-arabia-saudi-blog.jpg)

▲Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman and President Donald Trump during a meeting in Washington in 2017 [White House]

ANALYSIS / Naomi Moreno

Saudi Arabia used to be the only country in the world that banned women from driving. This ban was one of the things that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) was best known for to outsiders not otherwise familiar with the country's domestic politics, and has thus been a casus belli for activists demanding reforms in the kingdom. Last month, Saudi Arabia started issuing the first driver's licenses to women, putting into effect some of the changes promised by the infamous Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman (MBS) in his bid to modernize Saudi Arabian politics. The end of the ban further signals the beginning of a move to expand the rights of women in KSA, and builds on piecemeal developments that took place in the realm of women’s rights in the kingdom prior to MBS’ entrance to the political scene.

Thus, since 2012, Saudi Arabian women have been able to do sports as well as participate in the Olympic Games; in the 2016 Olympics, four Saudi women were allowed to travel to Rio de Janeiro to compete. Moreover, within the political realm, King Abdullah swore in the first 30 women to the shura council − Saudi Arabia's consultative council − in February 2013, and in the kingdom's 2015 municipal elections, women were able to vote and run for office for the first time. Finally, and highlighting the fact that economic dynamics have similarly played a role in driving progression in the kingdom, the Saudi stock exchange named the first female chairperson in its history − a 39-year-old Saudi woman named Sarah Al Suhaimi − last February.

Further, although KSA may be known to be one of the “worst countries to be a woman”, the country has experienced a notable breakthrough in the last 5 years and the abovementioned advances in women’s rights, to name some, constitute a positive development. However, the most visible reforms have arguably been the work of MBS. The somewhat rash and unprecedented decision to end the ban on driving coincided with MBS' crackdown on ultra-conservative, Wahhabi clerics and the placing of several of the kingdom's richest and most influential men under house arrest, under the pretext of challenging corruption. In addition, under his leadership, the oil-rich kingdom is undergoing economic reforms to reduce the country's dependency on oil, in a bid to modernize the country’s economy.

Nonetheless, despite the above mentioned reforms being classified by some as unprecedented, progressive leaps that are putting an end to oppression through challenging underlying ultra-conservatism traditions (as well as those that espouse them), a measure of distrust has arisen among Saudis and outsiders with regards the motivations underlying the as-of-yet seemingly limited reforms that have been introduced. While some perceive the crown prince's actions to be a genuine move towards reforming Saudi society, several indicators point to the possibility that MBS might have more practical reasons that are only tangentially related to progression for progression's sake. As the thinking goes, such decrees may have less to do with genuine reform, and more to do with improving an international image to deflect from some of the kingdom’s more controversial practices, both at home and abroad. A number of factors drive this public scepticism.

Reasons for scepticism

The first relates to the fact that KSA is a country where an ultraconservative form of shari'a or Islamic law continues to constitute the primary legal framework. This legal framework is based on the Qur'an and Hadith, within which the public and many private aspects of everyday life are regulated. Unlike in other Muslim majority countries, where only selective elements of the shari'a are adopted, Wahhabism – which is identified by the Court of Strasbourg as a main source of terrorism − has necessitated the strict adherence to a fundamentalist interpretation of shari'a, one that draws from the stricter and more literal Hanbali school of jurisprudence. As such, music and the arts have been strictly controlled and censored. In addition, although the religious police (more commonly known as the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice) have had their authority curbed to a certain degree, they are still given the authority to enforce Islamic norms of conduct in public by observing suspects and forwarding their findings to the police.

In the past few years, the KSA has been pushing for a more national Wahhabism, one that is more modern in its outlook and suitable for the kingdom’s image. Nevertheless, the Wahhabi clergy has been close to the Al Saud dynasty since the mid-18th century, offering it Islamic legitimacy in return for control over parts of the state, and a lavish religious infrastructure of mosques and universities. Therefore, Saudi clerics are pushing back significantly against democratization efforts. As a result, the continuing prevalence of a shari'a system of law raises questions about the ability of the kingdom to seriously democratise and reform to become moderate.

Secondly, and from a domestic point of view, Saudi Arabia is experiencing disharmony. Saudi citizens are not willing to live in a country where any political opposition is quelled by force, and punishments for crimes such as blasphemy, sorcery, and apostasy are gruesome and carried out publicly. This internal issue has thus embodied an identity crisis provoked mainly by the 2003 Iraq war, and reinforced by the events of the Arab Spring. Disillusionment, unemployment, religious and tribal splits, as well as human rights abuses and corruption among an ageing leadership have been among the main grievances of the Saudi people who are no longer as tolerant of oppression.

In an attempt to prevent the spill over of the Arab Spring fervor into the Kingdom, the government spent $130 billion in an attempt to offset domestic unrest. Nonetheless, these grants failed to satisfy the nearly 60 percent of the population under the age of twenty-one, which refused to settle. In fact, in 2016 protests broke out in Qatif, a city in Saudi Arabia's oil-rich, eastern provinces, which prompted Saudis to deploy additional security units to the region. In addition, in September of last year, Saudi authorities, arguing a battle against corruption and a crack down on extremism, arrested dozens of people, including prominent clerics. According to a veteran Saudi journalist, this was an absurd action as “there was nothing that called for such arrests”. He argued that several among those arrested were not members of any political organization, but rather individuals with dissenting viewpoints to those held by the ruling family.

Among those arrested was Sheikh Salman al-Awdah, an influential cleric known for agitating for political change and for being a pro-shari'a activist. Awdah's arrest, while potentially disguised as part of the kingdom’s attempts to curb the influence of religious hardliners, is perhaps better understood in the context of the Qatar crisis. Thus, when KSA, with the support of a handful of other countries in the region, initiated a blockade of the small Gulf peninsula in June of last year, Awdah welcomed a report on his Twitter account suggesting that the then three-month-old row between Qatar and four Arab countries led by Saudi Arabia may be resolved. The ensuing arrest of the Sheikh seems to confirm a suspicion that it was potentially related to his favouring the renormalization of relations with Qatar, as opposed to it being related to MBS' campaign to moderate Islam in the kingdom.

A third factor that calls into question the sincerity of the modernization campaign is economic. Although Saudi Arabia became a very wealthy country following the discovery of oil in the region, massive inequality between the various classes has grown since, as these resources remain to be controlled by a select few. As a result, nearly one fifth of the population continues to live in poverty, especially in the predominantly Shi’a South where, ironically, much of the oil reservoirs are located. In these areas, sewage runs in the streets, and only crumbs are spent to alleviate the plight of the poor. Further, youth opportunities in Saudi Arabia are few, which leaves much to be desire, and translates into occasional unrest. Thus, the lack of possibilities has led many young men to join various terrorist organizations in search of a new life.

|

Statement by MBS in a conference organized in Riyadh in October 2017 [KSA] |

Vision 2030 and international image

In the context of the Saudi Vision 2030, the oil rich country is aiming to wean itself of its dependence on the natural resource which, despite its wealth generation capacity, has also been one of the main causes of the country's economic problems. KSA is facing an existential crisis that has led to a re-think of its long-standing practice of selling oil via fixed contracts. This is why Vision 2030 is so important. Seeking to regain better control over its economic and financial destiny, the kingdom has designed an ambitious economic restructuring plan, spearheaded by MBS. Vision 2030 constitutes a reform programme that aims to upgrade the country’s financial status by diversifying its economy in a world of low oil prices. Saudi Arabia thus needs overseas firms’ investments, most notably in non-oil sectors, in order to develop this state-of-the-art approach. This being said, Vision 2030 inevitably implies reforms on simultaneous fronts that go beyond economic affairs. The action plan has come in at a time when the kingdom is not only dealing with oil earnings and lowering its reserves, but also expanding its regional role. As a result, becoming a more democratic country could attract foreign wealth to a country that has traditionally been viewed in a negative light due to its repressive human rights record.

This being said, Saudi Arabia also has a lot to do regarding its foreign policy in order to improve its international image. Despite this, the Saudi petition to push the US into a war with Iran has not ceased during recent years. Religious confrontation between the Sunni Saudi autocracy and Iran’s Shi’a theocracy has characterized the geopolitical tensions that have existed in the region for decades. Riyadh has tried to circumvent criticism of its military intervention in the Yemen through capitalizing on the Trump administration's hostility towards Iran, and involving the US in its campaign; thus granting it a degree of legitimacy as an international alliance against the Houthis. Recently, MBS stated that Trump was the “best person at the right time” to confront Iran. Conveniently enough, Trump and the Republicans are now in charge of US’ foreign affairs. Whereas the Obama administration, in its final months, suspended the sale of precision-guided missiles to Saudi Arabia, the Trump administration has moved to reverse this in the context of the Yemeni conflict. In addition, in May of this year, just a month after MBS visited Washington in a meeting which included discussions regarding the Iran accords, the kingdom has heaped praise on president Trump following his decision to withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal.

All things considered, 2018 may go down in history as the irreversible end of the absolute archaic Saudi monarchy. This implosion was necessitated by events, such as those previously mentioned, that Saudi rulers could no longer control or avoid. Hitherto, MBS seems to be fulfilling his father’s wishes. He has hand-picked dutiful and like-minded princes and appointed them to powerful positions. As a result, MBS' actions suggest that the kingdom is turning over a new page in which a new generation of princes and technocrats will lead the breakthrough to a more moderate and democratic Saudi Arabia.

New awareness

However, although MBS has declared that the KSA is moving towards changing existing guardianship laws, due to cultural differences among Saudi families, to date, women still need power of attorney from a male relative to acquire a car, and risk imprisonment should they disobey male guardians. In addition, this past month, at least 12 prominent women’s rights activists who campaigned for women's driving rights just before the country lifted the ban were arrested. Although the lifting of the ban is now effective, 9 of these activists remain behind bars and are facing serious charges and long jail sentences. As such, women continue to face significant challenges in realizing basic rights, despite the positive media endorsement that MBS' lifting of the driving ban has received.

Although Saudi Arabia is making an effort in order to satisfy the public eye, it is with some degree of scepticism that one should approach the country's motivations. Taking into account Saudi Arabia’s current state of affairs, these events suggest that the women’s driving decree was an effort in order to improve the country’s external image as well as an effort to deflect attention from a host of problematic internal and external affairs, such as the proxy warfare in the region, the arrest of dissidents and clerics this past September, and the Qatari diplomatic crisis, which recently “celebrated” its first anniversary. Allowing women to drive is a relatively trivial sacrifice for the kingdom to make and has triggered sufficient positive reverberations globally. Such baby steps are positive, and should be encouraged, yet overlook the fact that they only represent the tip of the iceberg.

As it stands, the lifting of the driving ban does not translate into a concrete shift in the prevailing legal and cultural mindsets that initially opposed it. Rather, it is an indirect approach to strengthen Saudi’s power in economic and political terms. Yet, although women in Saudi Arabia may feel doubtful about the government’s intentions, time remains to be their best ally. After decades of an ultraconservative approach to handling their rights, the country has reached awareness that it can no longer sustain its continued oppression of women; and this for economic reasons, but also as a result of global pressures that affect the success of the country's foreign policies which, by extension, also negatively impact on its interests.

The silver lining for Saudi woman is that, even if the issue of women's rights is being leveraged to secure the larger interests of the kingdom, it continues to represent a slow and steady progression to a future in which women may be granted more freedoms. The downside is that, so long as these rights are not grafted into a broader legal framework that secures them beyond the rule of a single individual − like MBS − women's rights (and human rights in general) will continue to be the temporary product of individual whim. Without an overhaul of the shari'a system that perpetuates regressive attitudes towards women, the best that can be hoped for is the continuation of internal and external pressures that coerce the Saudi leadership into exacting further reforms in the meantime. As with all things, time will tell.

DOC. DE TRABAJO / A. Palacios, M. Lamela, M. Biera [Versión en inglés]

RESUMEN

La Unión Europea (UE) se ha visto especialmente dañada internamente por campañas de desinformación que han cuestionado su legislación y sus mismos valores. Las distintas operaciones desinformativas y la incapacidad comunicativa de las instituciones de la Unión Europea han generado un sentimiento de alarma en Bruselas. Apenas un año antes de la celebración de las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo, Europa ha concentrado muchos de sus esfuerzos en hacer frente al desafío desinformativo, generando nuevas estrategias y grupos de trabajo como el Stratcom Task Force o el grupo de expertos de la Comisión Europea.

Descargar el documento completo [pdf. 381K]

Descargar el documento completo [pdf. 381K]

Tras siglos de orientación caribeña, el enclave acentúa la relación con sus vecinos del continente

Hace dos años, Surinam y Guyana pasaron a formar parte de la federación sudamericana de fútbol, abandonando la federación de Norteamérica, Centroamérica y el Caribe a la que pertenecían. Es un claro símbolo del cambio de orientación geográfica que está operando este rincón noreste sudamericano que, como en el caso del fútbol, ve el potencial de una mayor relación con sus vecinos del sur.

ARTÍCULO / Alba Redondo

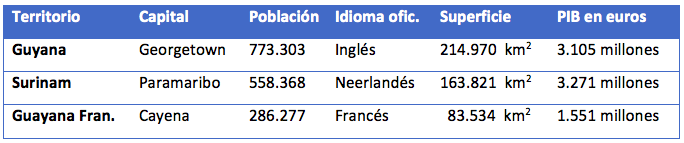

Como vestigios del pasado colonial de las grandes potencias navales europeas del siglo XVII –Inglaterra, Holanda y Francia–, encontramos en el noreste de Sudamérica las tres Guayanas: Guyana, Surinam y la Guayana Francesa. Además de las barreras naturales que aíslan la región y dificultan su conexión con el resto del continente sudamericano –tiene más relación con el Caribe, aunque su costa atlántica queda fuera de ese mar–, existen también barreras sociales, culturales e idiomáticas que complican su integración en el continente.

Situada al noreste del continente sudamericano, la región fue denominada Guayana o “tierra de muchas aguas” por sus habitantes originales, los Arahuacos. El área limita al oeste con Venezuela y al sur con Brasil, países que también incluyen tierras que forman parte de la región natural guayanesa. Los terrenos húmedos y costas tupidas de manglares y pantanos, se aúnan con el clima tropical del interior, particular por sus selvas vírgenes, sus altiplanos y sus grandes cordilleras como el Escudo guayanés. Su población, que va desde indígenas hasta descendientes europeos, se localiza en el área costera y en los valles de los ríos.

Se habla de las Guayanas de manera conjunta no solo por formar un territorio común para los nativos, sino también por quedar al margen del reparto continental que hicieron los dos grandes imperios de la Península Ibérica. Siendo un territorio de no fácil acceso desde el resto del continente, la falta de presencia de españoles y portugueses propició que otras potencias europeas del momento buscaran poner allí un pie, en campañas de exploración llevadas a cabo durante el siglo XVII. La Guayana inglesa ganó la independencia en 1970 y la holandesa lo hizo en 1975. La Guayana Francesa sigue siendo un departamento y una región de ultramar de Francia y, por consiguiente, un territorio ultraperiférico de la Unión Europea en Sudamérica.

Las tres desconocidas

Al oeste de la región se encuentra Guyana, conocida oficialmente como República Cooperativa de Guyana. El país tiene una población en torno a 773.000 habitantes, localizados mayoritariamente en Georgetown, su capital. Su idioma oficial es el inglés, legado de su pasado colonial. La realidad política-social guyanesa está marcada por la convivencia conflictiva entre los dos grandes grupos étnicos: los afroguyaneses y los indoguyaneses. Su política interior se caracteriza por el bipartidismo entre el PNC (People´s National Congress) formado por los afrodescendientes concentrados en los centros urbanos; y el PPP (People Progressive Party), con mayor influencia en la zona rural, constituido por descendientes de inmigrantes de la India llegados durante el Imperio británico y que trabajan en las plantaciones de azúcar.

Pese a un reciente aumento de la inversión extranjera, Guyana es el país más pobre y con mayor índice de criminalidad, violencia y suicidio del continente. Además, su imagen internacional está condicionada por su percepción como área referente en la distribución internacional de cocaína y su elevado índice de corrupción. Sin embargo, el futuro del país apunta a un ingreso dentro de las grandes potencias petroleras mundiales tras el descubrimiento de uno de los mayores yacimientos de petróleo y gas descubierto en nuestra década.

Al igual que Guyana, la vida política de la República de Surinam está sujeta a un gran mosaico étnico-cultural. La antigua colonia neerlandesa, con capital en Paramaribo, es el país más pequeño y menos poblado de Sudamérica, con tan solo 163. 821 habitantes. Tras su independencia en 1975, más de un tercio de la población emigró a la metrópolis (Holanda). Esto produjo una gran crisis estructural por la falta de capital humano en el país. Surinam está conformado por descendientes de casi todos los continentes: africanos, indios, chinos y javaneses, aborígenes y europeos. Su política interior está marcada por la influencia de Desiré Bouterse y por las aspiraciones democráticas de la sociedad. Respecto a su política exterior, Surinam apuesta por un mejor control de las exportaciones de sus recursos, principalmente el aluminio, y por una progresiva integración en la esfera regional e internacional, en la mayoría de los casos, junto a su país vecino, Guyana.

A diferencia de las otras dos Guayanas, Guayana francesa no es un país independiente, sino que se trata de una región de ultramar de Francia, de la que se encuentra a más de 7.000 km de Francia. La capital de este territorio es Cayena. Durante mucho tiempo fue utilizada por Francia como colonia penal. Tiene la tasa de homicidio más alta de todo el territorio francófono y es conocida por su alto nivel de criminalidad. Como departamento galo, es parte de la Unión Europea y sede del Centro Espacial Guayanés, albergando una de las principales estaciones europeas de lanzamiento de satélites en Kourou. Guayana francesa se enfrenta al creciente desempleo, la falta de recursos para la educación y la insatisfacción de su población que ha dado lugar a numerosas protestas.

|

Cambio de orientación

Debido a la fuerte relación histórica con sus respectivas metrópolis y a su independencia tardía, tradicionalmente ha existido una importante barrera entre las Guayanas y Sudamérica. Geográficamente se encuentran arrinconadas en la costa norte de Sudamérica, con dificultad de desarrollar contactos hacia el sur, debido a la orografía del macizo guayanés y la selva amazónica. Pero también ha habido razones culturales y lingüísticas que contribuyeron a una aproximación entre esta región y el oeste caribeño, donde Inglaterra, Holanda y Francia tuvieron –y siguen teniendo en algunos casos– posesiones isleñas.

Sin embargo, tras un gran periodo de relativo aislamiento, de apenas relación con vecinos sureños, las repúblicas de Surinam y Guyana han empezado a incorporarse a la dinámica de integración económica y política de América del Sur.

Tradicionalmente, los dos Estados han tenido una mayor relación con el Caribe: ambos son miembros plenos del CARICOM, siendo Georgetown la sede de esta comunidad de países caribeños, y forman parte de la Asociación de Estados del Caribe (AEC), con la peculiaridad de la presencia de Guayana Francesa como asociado. En los últimos años, Surinam y Guayana han comenzado a mirar más hacia el propio continente: así han participado en la creación de Unasur y son países observadores de Mercosur. Símbolo de ese cambio de orientación fue el ingreso en 2016 de esos dos países en Conmebol, la federación sudamericana de fútbol, abandonando la federación de Norteamérica, Centroamérica y el Caribe a la que pertenecían.

Esa mayor relación con sus vecinos continentales y la participación en el proceso de integración sudamericano debiera servir para resolver algunas cuestiones limítrofes pendientes, como la disputa que mantienen Venezuela y Guyana: Caracas ha reclamado históricamente el territorio que se extiende entre su frontera y el río Esequibo, que discurre por la mitad Guyana. No obstante, a medida que otras controversias territoriales latinoamericanas se van resolviendo en los tribunales internacionales, la del Esequibo amenaza de momento con perpetuarse.

ESSAY / Elena López-Dóriga

The European Union’s aim is to promote democracy, unity, integration and cooperation between its members. However, in the last years it is not only dealing with economic crises in many countries, but also with a humanitarian one, due to the exponential number of migrants who run away from war or poverty situations.

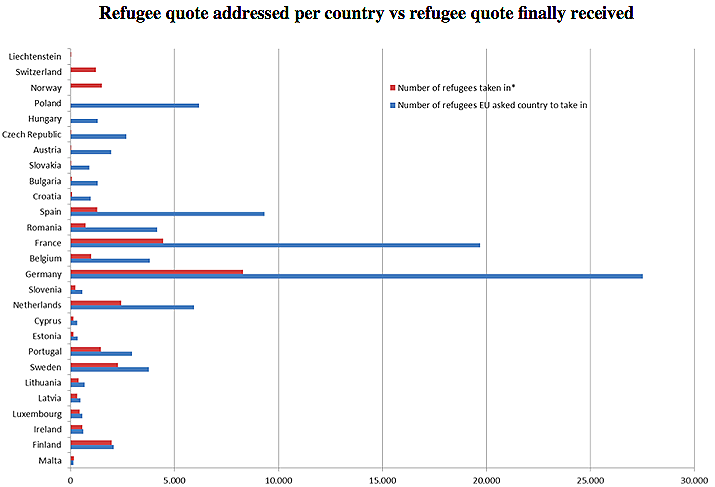

When referring to the humanitarian crises the EU had to go through (and still has to) it is about the refugee migration coming mainly from Syria. Since 2011, the civil war in Syria killed more than 470,000 people, mostly civilians. Millions of people were displaced, and nearly five million Syrians fled, creating the biggest refugee crisis since the World War II. When the European Union leaders accorded in assembly to establish quotas to distribute the refugees that had arrived in Europe, many responses were manifested in respect. On the one hand, some Central and Eastern countries rejected the proposal, putting in evidence the philosophy of agreement and cooperation of the EU claiming the quotas were not fair. Dissatisfaction was also felt in Western Europe too with the United Kingdom’s shock Brexit vote from the EU and Austria’s near election of a far right-wing leader attributed in part to the convulsions that the migrant crisis stirred. On the other hand, several countries promised they were going to accept a certain number of refugees and turned out taking even less than half of what they promised. In this note it is going to be exposed the issue that occurred and the current situation, due to what happened threatened many aspects that revive tensions in the European Union nowadays.

The response of the EU leaders to the crisis

The greatest burden of receiving Syria’s refugees fell on Syria’s neighbors: Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. In 2015 the number of refugees raised up and their destination changed to Europe. The refugee camps in the neighbour countries were full, the conditions were not good at all and the conflict was not coming to an end as the refugees expected. Therefore, refugees decided to emigrate to countries such as Germany, Austria or Norway looking for a better life. It was not until refugees appeared in the streets of Europe that European leaders realised that they could no longer ignore the problem. Furthermore, flows of migrants and asylum seekers were used by terrorist organisations such as ISIS to infiltrate terrorists to European countries. Facing this humanitarian crisis, European Union ministers approved a plan on September 2015 to share the burden of relocating up to 120,000 people from the so called “Frontline States” of Greece, Italy and Hungary to elsewhere within the EU. The plan assigned each member state quotas: a number of people to receive based on its economic strength, population and unemployment. Nevertheless, the quotas were rejected by a group of Central European countries also known as the Visegrad Group, that share many interests and try to reach common agreements.

Why the Visegrad Group rejected the quotas

The Visegrad Group (also known as the Visegrad Four or simply V4) reflects the efforts of the countries of the Central European region to work together in many fields of common interest within the all-European integration. The Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia have shared cultural background, intellectual values and common roots in diverse religious traditions, which they wish to preserve and strengthen. After the disintegration of the Eastern Block, all the V4 countries aspired to become members of the European Union. They perceived their integration in the EU as another step forward in the process of overcoming artificial dividing lines in Europe through mutual support. Although they negotiated their accession separately, they all reached this aim in 2004 (1st May) when they became members of the EU.

The tensions between the Visegrad Group and the EU started in 2015, when the EU approved the quotas of relocation of the refugees only after the dissenting votes of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia were overruled. In asking the court to annul the deal, Hungary and Slovakia argued at the Court of Justice that there were procedural mistakes, and that quotas were not a suitable response to the crisis. Besides, the politic leaders said the problem was not their making, and the policy exposed them to a risk of Islamist terrorism that represented a threat to their homogenous societies. Their case was supported by Polish right-wing government of the party Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice) which came to power in 2015 and claimed that the quotes were not comprehensive.

Regarding Poland’s rejection to the quotas, it should be taken into account that is a country of 38 million people and already home to an exponential number of Ukrainian immigrants. Most of them decided to emigrate after military conflict erupted in eastern Ukraine in 2014, when the currency value of the Ukrainian hryvnia plummeted and prices rose. This could be a reason why after having received all these immigration from Ukraine, the Polish government believed that they were not ready to take any more refugees, and in that case from a different culture. They also claimed that the relocation methods would only attract more waves of immigration to Europe.

The Slovak and Hungarian representatives at the EU court stressed that they found the Council of the EU’s decision rather political, as it was not achieved unanimously, but only by a qualified majority. The Slovak delegation labelled this decision “inadequate and inefficient”. Both the Slovak and Hungarian delegations pointed to the fact that the target the EU followed by asserting national quotas failed to address the core of the refugee crisis and could have been achieved in a different way, for example by better protecting the EU’s external border or with a more efficient return policy in case of migrants who fail to meet the criteria for being granted asylum.

The Czech prime minister at that time, Bohuslav Sobotka, claimed the commission was “blindly insisting on pushing ahead with dysfunctional quotas which decreased citizens’ trust in EU abilities and pushed back working and conceptual solutions to the migration crisis”.

Moreover, there are other reasons that run deeper about why ‘new Europe’ (these recently integrated countries in the EU) resisted the quotas which should be taken into consideration. On the one hand, their just recovered sovereignty makes them especially resistant to delegating power. On the other, their years behind the iron curtain left them outside the cultural shifts taking place elsewhere in Europe, and with a legacy of social conservatism. Furthermore, one can observe a rise in skeptical attitudes towards immigration, as public opinion polls have shown.

|

* As of September 2017. Own work based on this article |

The temporary solution: The Turkey Deal

The accomplishment of the quotas was to be expired in 2017, but because of those countries that rejected the quotas and the slow process of introducing the refugees in those countries that had accepted them, the EU reached a new and polemic solution, known as the Turkey Deal.

Turkey is a country that has had the aspiration of becoming a European Union member since many years, mainly to improve their democracy and to have better connections and relations with Western Europe. The EU needed a quick solution to the refugee crisis to limit the mass influx of irregular migrants entering in, so knowing that Turkey is Syria’s neighbor country (where most refugees came from) and somehow could take even more refugees, the EU and Turkey made a deal the 18th of March 2016. Following the signing of the EU-Turkey deal: those arriving in the Greek Islands would be returned to Turkey, and for each Syrian sent back from Greece to Turkey one Syrian could be sent from a Turkish camp to the EU. In exchange, the EU paid 3 billion euros to Turkey for the maintenance of the refugees, eased the EU visa restrictions for Turkish citizens and payed great lip-service to the idea of Turkey becoming a member state.

The Turkey Deal is another issue that should be analysed separately, since it has not been defended by many organisations which have labelled the deal as shameless. Instead, the current relationship between both sides, the UE and V4 is going to be analysed, as well as possible new solutions.

Current relationship between the UE and V4

In terms of actual relations, on the one hand critics of the Central European countries’ stance over refugees claim that they are willing to accept the economic benefits of the EU, including access to the single market, but have shown a disregard for the humanitarian and political responsibilities. On the other hand, the Visegrad Four complains that Western European countries treat them like second-class members, meddling in domestic issues by Brussels and attempting to impose EU-wide solutions against their will, as typified by migrant quotas. One Visegrad minister told the Financial Times, “We don’t like it when the policy is defined elsewhere and then we are told to implement it.” From their point of view, Europe has lost its global role and has become a regional player. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban said “the EU is unable to protect its own citizens, to protect its external borders and to keep the community together, as Britain has just left”.

Mr Avramopolus, who is Greece’s European commissioner, claimed that if no action was taken by them, the Commission would not hesitate to make use of its powers under the treaties and to open infringement procedures.

At this time, no official sanctions have been imposed to these countries yet. Despite of the threats from the EU for not taking them, Mariusz Blaszczak, Poland´s former Interior minister, claimed that accepting migrants would have certainly been worse for the country for security reasons than facing EU action. Moreover, the new Poland’s Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki proposes to implement programs of aid addressed to Lebanese and Jordanian entities on site, in view of the fact that Lebanon and Jordan had admitted a huge number of Syrian refugees, and to undertake further initiatives aimed at helping the refugees affected by war hostilities.

To sum up, facing this refugee crisis a fracture in the European Union between Western and Eastern members has showed up. Since the European Union has been expanding its boarders from west to east integrating new countries as member states, it should also take into account that this new member countries have had a different past (in the case of the Eastern countries, they were under the iron curtain) and nowadays, despite of the wish to collaborate all together, the different ideologies and the different priorities of each country make it difficult when it comes to reach an agreement. Therefore, while old Europe expects new Europe to accept its responsibilities, along with the financial and security benefits of the EU, this is going to take time. As a matter of fact, it is understandable that the EU Commission wants to sanction the countries that rejected the quotas, but the majority of the countries that did accept to relocate the refugees in the end have not even accepted half of what they promised, and apparently they find themselves under no threats of sanction. Moreover, the latest news coming from Austria since December 2017 claim that the country has bluntly told the EU that it does not want to accept any more refugees, arguing that it has already taken in enough. Therefore, it joins the Visegrad Four countries to refuse the entrance of more refugees.

In conclusion, the future of Europe and a solution to this problem is not known yet, but what is clear is that there is a breach between the Western and Central-Eastern countries of the EU, so an efficient and fair solution which is implemented in common agreement will expect a long time to come yet.

Bibliography:

J. Juncker. (2015). A call for Collective Courage. 2018, de European Commission Sitio web.

EC. (2018). Asylum statistics. 2018, de European Commission Sitio web.

International Visegrad Fund. (2006). Official Statements and communiqués. 2018, de Visegrad Group Sitio web.

Jacopo Barigazzi (2017). Brussels takes on Visegrad Group over refugees. 2018, de POLITICO Sitio web.

Zuzana Stevulova (2017). “Visegrad Four” and refugees. 2018, de Confrontations Europe (European Think Tank) Sitio web.

Nicole Gnesotto. (2015). Refugees are an internal manifestation of an unresolved external crisis. 2018, de Confrontations Europe (European Think Tank) Sitio web.

Trump ha mantenido varias de las medidas aprobadas por Obama, pero ha condicionado su aplicación

Donald Trump no ha cerrado la embajada abierta por Barack Obama en La Habana y se ha ajustado a la letra de las normas que permiten solo ciertos viajes de estadounidenses a la isla. Sin embargo, su imposición de no establecer relaciones comerciales o financieras con empresas controladas por el aparato militar-policial cubano ha afectado al volumen de intercambios. Pero ha sido sobre todo su retórica anticastrista la que ha devuelto la relación casi a la Guerra Fría.

![Barack Obama y Raúl Castro, en el partido de béisbol al que acudieron durante la visita del presidente estadounidense a Cuba, en 2016 [Pete Souza/Casa Blanca] Barack Obama y Raúl Castro, en el partido de béisbol al que acudieron durante la visita del presidente estadounidense a Cuba, en 2016 [Pete Souza/Casa Blanca]](/documents/10174/16849987/eeuu-cuba-blog.jpg)

▲Barack Obama y Raúl Castro, en el partido de béisbol al que acudieron durante la visita del presidente estadounidense a Cuba, en 2016 [Pete Souza/Casa Blanca]

ARTÍCULO / Valeria Vásquez

Durante más de medio siglo las relaciones entre Estados Unidos y Cuba estuvieron marcadas por las tensiones políticas. Los últimos años de la presidencia de Barack Obama marcaron un significativo cambio con el histórico restablecimiento de las relaciones diplomáticas entre ambos países y la aprobación de ciertas medidas de apertura de Estados Unidos hacia Cuba. La Casa Blanca esperaba entonces que el clima de creciente cooperación impulsara las modestas reformas económicas que La Habana había comenzado a aplicar con antelación y que todo ello trajera con el tiempo transformaciones políticas a la isla.

La falta de concesiones del Gobierno cubano en materia de libertades y derechos humanos, sin embargo, fue esgrimida por Donald Trump para dar marcha atrás, a su llegada al poder, a varias de las medidas aprobadas por su antecesor, si bien ha sido sobre todo su retórica anticastrista la que ha creado un nuevo ambiente hostil entre Washington y La Habana.

Era Obama: distensión

En su segundo mandato, Barack Obama comenzó negociaciones secretas con Cuba que culminaron con el anuncio en diciembre de 2014 de un acuerdo para el restablecimiento de relaciones diplomáticas entre los dos países. Las respectivas embajadas fueron reabiertas en julio de 2015, dando así por superada una anomalía que databa de 1961, cuando la Administración Eisenhower decidió romper relaciones con el vecino antillano ante la orientación comunista de la Revolución Cubana. En marzo de 2016 Obama se convirtió en el primer presidente estadounidense en visitar Cuba en 88 años.

Más allá de la esfera diplomática, Obama procuró también una apertura económica hacia la isla. Dado que levantar el embargo establecido por EEUU desde hace décadas requería la aprobación del Congreso, donde se enfrentaba a la mayoría republicana, Obama introdujo ciertas medidas liberalizadoras mediante decretos presidenciales. Así, rebajó las restricciones de viaje (apenas cambió la letra de la ley, pero sí relajó su práctica) y autorizó elevar el volumen de compras que los estadounidenses podían hacer en Cuba.

Para Obama, el embargo económico era una política fallida, pues no había logrado su propósito de acabar con la dictadura cubana y, por consiguiente, había prolongado esta. Por ello, apostaba por un cambio de estrategia, con la esperanza de que la normalización de las relaciones –diplomáticas y, progresivamente, económicas– ayudaran a mejorar la situación social de Cuba y contribuyeran, a medio o largo plazo, al cambio que el embargo económico no ha conseguido. Según Obama, este había tenido un impacto negativo, pues asuntos como la limitación del turismo o la poca inversión extranjera directa habían afectado más al pueblo cubano que a la nomenclatura castrista.

Una nueva relación económica

Ante la imposibilidad de levantar el embargo económico a Cuba, Obama optó por decretos presidenciales que abrían algo las relaciones comerciales entre los dos países. Varias medidas iban dirigidas a facilitar un mejor acceso a internet de los cubanos, lo que debiera contribuir a impulsar exigencias democratizadoras en el país. Así, Washington autorizó que empresas de telecomunicaciones americanas establecieran negocios en Cuba.

En el campo financiero, Estados Unidos permitió que sus bancos abrieran cuentas en Cuba, lo que facilitó la realización de transacciones. Además, los ciudadanos cubanos residentes en la isla podían recibir pagos en EEUU y enviarlos de vuelta a su país.

Otra de las medidas adoptadas fue el levantamiento de algunas de las restricciones de viaje. Por requerimiento de la legislación de EEUU, Obama mantuvo la restricción de que los estadounidenses solo pueden viajar a Cuba bajo diversos supuestos, todos vinculados a determinadas misiones: viajes con finalidad académica, humanitaria, de apoyo religioso... Aunque seguían excluidos los viajes puramente turísticos, la falta de control que deliberadamente las autoridades estadounidenses dejaron de aplicar significaba abrir considerablemente la mano.

Además de autorizar las transacciones bancarias relacionadas con dichos viajes, para atender el previsto incremento de turistas se anunció que varias compañías aéreas estadounidenses como JetBlue y American Airlines habían recibido la aprobación para volar a Cuba. Por primera vez en 50 años, a finales de noviembre de 2016 un avión comercial estadounidense aterrizaba en La Habana.

El presidente estadounidense también eliminó el límite de gasto que tenían los visitantes estadounidenses en la compra de productos de uso personal (singularmente cigarros puros y ron). Asimismo, promovió la colaboración en la investigación médica y aprobó la importación de medicinas producidas en Cuba.

Además, Obama revocó la política de “pies secos, pies mojados”, por la que los cubanos que llegaban a suelo de Estados Unidos recibían automáticamente el asilo político, mientras que solo eran devueltos a la isla aquellos que fueran interceptados por Cuba en el mar.

La revisión de Trump

Desde su campaña electoral, Donald Trump mostró señales claras sobre el rumbo que tomarían sus relaciones con Cuba si alcanzaba la presidencia. Trump anunció que revertiría la apertura hacia Cuba llevada a cabo por Obama, y nada más llegar a la Casa Blanca comenzó a robustecer el discurso anticastrista de Washington. El nuevo presidente dijo estar dispuesto a negociar un “mejor acuerdo” con la isla, pero con la condición de que el Gobierno cubano mostrara avances concretos hacia la democratización del país y el respeto de los derechos humanos. Trump planteó un horizonte de elecciones libres y la liberación de prisioneros políticos, a sabiendas de que el régimen cubano no accedería a esas peticiones. Ante la falta de respuesta de La Habana, Trump insistió en sus propuestas previas: mantenimiento del embargo (que en cualquier caso la mayoría republicana en el Congreso no está dispuesta a levantar) y marcha atrás en algunas de las decisiones de Obama.

En realidad, Trump ha mantenido formalmente varias de las medidas de su antecesor, si bien la prohibición de hacer negocios con las compañías controladas por las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias (FAR), que dominan buena parte de la vida económica cubana, y el respeto por la letra en las restricciones de viajes han reducido el contacto entre EEUU y Cuba que había comenzado a darse al final de la era Obama.

Trump ha ratificado la derogación de la política de “pies secos, pies mojados” decidida por Obama y ha mantenido las relaciones diplomáticas restablecidas por este (aunque ha paralizado el nombramiento de un embajador). También ha respetado la tímida apertura comercial y financiera operada por el presidente demócrata, pero siempre que las transacciones económicas no sucedan con las empresas vinculadas al Ejército, la inteligencia y los servicios de seguridad cubanos. En tal sentido, el Departamento del Tesoro publicó el 8 de noviembre de 2017 una lista de empresas de esos sectores con los que no cabe ningún tipo de contacto estadounidense.

En cuanto a los viajes, se mantienen los restringidos supuestos para los desplazamientos de estadounidenses a la isla, pero frente a la vista gorda adoptada por la Administración Obama, la Administración Trump exige que los estadounidenses que quieran ir a Cuba deberán hacerlo en tours realizados por empresas americanas, acompañados por un representante del grupo patrocinador y con la obligación de comunicar los detalles de sus actividades. La normativa del Tesoro requiere que las estancias sean en hostales privados (casas particulares), las comidas en restaurantes regentados por individuos (paladares) y se compre en tiendas sostenidas por ciudadanos (cuentapropistas), con el propósito de “canalizar los fondos” lejos del ejercito cubano y debilitar la política comunista.

La reducción de las expectativas turísticas llevó ya a finales de 2017 a que varias aerolíneas estadounidenses hubieran cancelado todos sus vuelos a la isla caribeña. La economía cubana había contado con un gran aumento de turistas de EEUU y sin embargo ahora debía enfrentarse, sin mayores ingresos, al grave problema de la caída de los envíos de petróleo barato de Venezuela.

Futuro de las relaciones diplomáticas

La mayor tensión entre Washington y La Habana, sin embargo, no ha estado en el ámbito comercial o económico, sino en el diplomático. Tras una serie de aparentes “ataques sónicos” a diplomáticos estadounidenses en Cuba, Estados Unidos retiró a gran parte de su personal en Cuba y expulsó a 15 diplomáticos de la embajada cubana en Washington. Además, el Departamento de Estado hizo una recomendación de no viajar a la isla. Si bien no se ha aclarado el origen de esos supuestos ataques, que las autoridades cubanas niegan haber realizado, podría tratarse del efecto secundario accidental de un intento de espionaje, que finalmente habría acabado causando daños cerebrales en las personas objeto de seguimiento.

El futuro de las relaciones entre los dos países dependerá del rumbo que tomen las políticas de Trump y del paso de las reformas que pueda establecer el nuevo presidente cubano. Dado que no se prevén muchos cambios en la gestión de Miguel Díaz-Canel, al menos mientras viva Raúl Castro, el inmovilismo de La Habana en el campo político y económico se seguiría topando probablemente con la retórica antirevolucionaria de Trump.

Los emigrantes del Triángulo Norte centroamericano miran a EEUU; los de Nicaragua, a Costa Rica

Mientras los emigrantes de Guatemala, El Salvador y Honduras siguen intentando llegar a Estados Unidos, los de Nicaragua han preferido en los últimos años viajar a Costa Rica. Las restricciones puestas en marcha por la Administración Trump y el deterioro de la bonanza económica costarricense están reduciendo los flujos, pero esa divisoria migratoria en Centroamérica de momento se mantiene.

▲Paso fronterizo entre México y Belice [Marrovi/CC]

ARTÍCULO / Celia Olivar Gil

Cuando se compara el grado de desarrollo de los países de Centroamérica, se entienden bien los distintos flujos humanos que operan en la región. Estados Unidos es el gran imán migratorio, pero también Costa Rica es en cierta medida un polo de atracción, evidentemente en menor grado. Así, los cinco países centroamericanos con mayor tasa de pobreza –Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua y Belice– reparten su orientación migratoria: los cuatro primeros mantienen importantes flujos hacia EEUU, mientras que en los últimos años Nicaragua ha optado más por Costa Rica, dada su cercanía.

Migración del Triángulo Norte a EEUU

Cerca de 500.000 personas intentan cada año por la frontera Sur de México con el objetivo de llegar a Estados Unidos. La mayoría proceden de Guatemala, El Salvador y Honduras, la región centroamericana conocida como Triángulo Norte y que es, hoy por hoy, una de las más violentas del mundo. Las razones que llevan a ese elevado número de ciudadanos del Triángulo Norte a emigrar, muchos de forma ilegal, son varias:

Por una parte, hay razones que podrían calificarse de estructurales: la porosidad del trazado fronterizo, la complejidad y los costes elevados de los procesos de regularización para la migración, la falta de compromiso de los empleadores para regularizar a los trabajadores inmigrantes y la capacidad insuficiente de los gobiernos para establecer leyes migratorias.

También hay claras razones económicas: Guatemala, Honduras y El Salvador tienen una alta tasa de pobreza, situada en el 67,7%, el 74,3% y el 41,6%, respectivamente, de sus habitantes. Las dificultades de ingresos presupuestarios y pronunciada desigualdad social suponen una presentación deficiente de servicios públicos, como educación y sanidad, a gran parte de la población.

La razón de mayor peso es quizá la falta de seguridad. Muchos de los que salen de esos tres países alegan la inseguridad y la violencia como el principal motivo de su marcha. Y es que el nivel de violencia criminal en el Triángulo Norte alcanza niveles semejantes a los de un conflicto armado. En El Salvador se registraron en 2015 un total de 6.650 homicidios intencionados; en Honduras, 8.035, y en Guatemala, 4.778.

Todos esos motivos empujan a guatemaltecos, salvadoreños y hondureños a emigrar a Estados Unidos, que en su viaje hacia el norte usan tres rutas principales para cruzar México: la que atraviesa en diagonal el país hasta llegar al área de Tijuana, la que avanza por el centro de México hasta Ciudad Juárez y la que busca entrar en EEUU por el valle del Río Bravo. A lo largo de esas rutas, los migrantes deben hacer frente a muchos riesgos, como el de ser víctima de organizaciones criminales y sufrir todo tipo de abusos (secuestro, tortura, violación, robo, extorsión...), algo que no solo puede causar lesiones físicas y traumas inmediatos, sino que también puede dejar graves secuelas a largo plazo.

Pese a todas estas dificultades, los ciudadanos del Triángulo norte siguen eligiendo los Estados Unidos como destino de su migración. Esto es debido principalmente a la atracción que supone el potencial económico de un país como EEUU, en situación de pleno empleo; a su relativa proximidad geográfica (es posible llegar por tierra atravesando solo uno o dos países), y a las relaciones humanas creadas desde la década de 1980, cuando EEUU comenzó a ser meta de quienes huían de las guerras civiles de una Centroamérica inestable políticamente y con dificultades económicas, lo que creó una tradición migratoria, consolidada por las conexiones familiares y la protección a los recién llegados ofrecida por los connacionales ya establecidos. Esto hizo que durante esta época la población centroamericana en EEUU se triplicase. En la actualidad el 82,9% de los inmigrantes centroamericanos en EEUU.

|

El 'parteaguas' migratorio americano [con autorización de ABC] |

Migración de Nicaragua a Costa Rica

Si la emigración del norte de Centroamérica se ha dirigido hacia Estados Unidos, la del sur de Centroamérica ha contado con más destinos. Si los hondureños han mirado al norte, en los últimos años sus vecinos nicaragüenses se han fijado algo más en el sur. El río Coco, que divide Honduras y Nicaragua, ha venido a ser una suerte de 'parteaguas' migratorio.

Ciertamente hay más nicaragüenses residentes oficialmente en EEUU (más de 400.000) que en Costa Rica (cerca de 300.000), pero en los últimos años el número de nuevos residentes ha aumentado más en territorio costarricense. En el último decenio, de acuerdo con un informe de la OEA (páginas 159 y 188), EEUU ha concedido el permiso de residencia permanente a una media de 3.500 nicaragüenses cada año, mientras que Costa Rica ha otorgado unos 5.000 de media, llegando al récord de 14.779 en 2013. Además, el peso proporcional de la migración nicaragüense en Costa Rica, un país de 4,9 millones de habitantes, es grande: en 2016, unos 440.000 nicaragüenses entraron en el vecino país, y se registraron otras tantas salidas, lo que indica una importante movilidad transfronteriza y sugiere que muchos trabajadores regresan temporalmente a Nicaragua para burlar los requisitos de extranjería.

Costa Rica es vista en ciertos aspectos en Latinoamérica como Suiza en Europa, es decir, como un país institucionalmente sólido, políticamente estable y económicamente favorable. Eso hace que la emigración de costarricenses no sea extrema y que en cambio lleguen personas de otros lugares, de forma que Costa Rica es el país con mayor migración neta de Latinoamérica, con un 9% de población de Costa Rica de origen extranjero.

Desde su independencia en la década de 1820, Costa Rica se ha mantenido como uno de los países centroamericanos con menor cantidad de conflictos graves. Por ello fue durante las décadas de 1970 y 1980 el refugio de muchos nicaragüenses que huían de la dictadura de los Somoza y de la revolución sandinista. Ahora, sin embargo, no emigran por razones de seguridad, pues Nicaragua es uno de los países menos violentos de Latinoamérica, incluso por debajo de las cifras de Costa Rica. Este flujo migratorio se debe a razones económicas: el mayor desarrollo de Costa Rica queda reflejado en la tasa de pobreza, que es del 18.6%, frente a la del 58.3% de Nicaragua; de hecho, Nicaragua es el país más pobre de América después de Haití.

Así mismo, los nicaragüenses tienen especial preferencia para elegir Costa Rica como lugar de destino por la cercanía geográfica, que les permite moverse con frecuencia entre los dos países y mantener hasta cierto punto la convivencia familiar; la utilización del mismo idioma, y otras similitudes culturales.

[Omar Jaén Suárez, 500 años de la cuenca del Pacífico. Hacia una historia global. Ediciones Doce Calles, Aranjuez 2016, 637 páginas]

RESEÑA / Emili J. Blasco

En solo treinta años, entre la llegada de Colón a América en 1492 y el regreso de Elcano a Cádiz tras su vuelta al mundo en 1522, España agregó a sus dominios no solo un nuevo continente, sino también un nuevo océano. Todos sabemos de la dimensión atlántica de España, pero con frecuencia desconsideramos su dimensión pacífica. Durante el siglo XVI y principios del XVII, el océano Pacífico estuvo fundamentalmente bajo dominio español. España fue la potencia europea presente durante más tiempo y con mayor peso en toda la cuenca de lo que comenzó llamándose Mar del Sur. Española fue la primera Armada que patrulló con regularidad sus aguas –la Armada del Sur, con base en El Callao peruano– y española fue la primera ruta comercial que periódicamente lo cruzó de lado a lado –el galeón de Manila, entre Filipinas y México.

|

En “500 años de la cuenca del Pacífico. Hacia una historia global”, el diplomático e historiador panameño Omar Jaén Suárez no se limita a documentar esa presencia española y luego hispana, en un vasto espacio –un tercio de la esfera de la Tierra y la mitad de sus aguas– cuyo margen oriental es la costa de Hispanoamérica. Lo suyo, como indica el título, es una historia global. Pero abordar el último medio milenio quiere decir que se parte del hecho del descubrimiento del Pacífico por los españoles y eso determina el enfoque de la narración.

Si la historiografía anglosajona habría quizás utilizado otro prisma, en este libro se pone el acento en el desarrollo de toda la cuenta del Pacífico a partir de la llegada de los primeros europeos, con Núñez de Balboa a la cabeza. Sin olvidar los hechos colonizadores de otras potencias, el autor detalla aspectos que los españoles sí olvidamos, como la base permanente que España tuvo en Formosa (hoy Taiwán), los intentos de la Corona para quedarse con Tahití o las travesías por Alaska en busca de un paso marítimo al norte de América, que tuvieron como punto logístico la isla de Quadra y Vancouver, la gran ciudad canadiense hoy conocida solo por la segunda parte de ese nombre (de hecho, España descuidó poblar Oregón, más interesada en Filipinas y el comercio con las Molucas: todo un pionero “giro hacia Asia”).

Ser de Panamá otorga a Omar Jaén, que ha vivido también en España, una sensibilidad especial por su materia de estudio. El istmo panameño fue siempre la llave del Mar del Sur para el Viejo Mundo; con la construcción del canal, además, Panamá es punto de tránsito entre Oriente y Occidente.

La cuidada edición de esta obra le añade un valor incontestable. Casi ochocientos mapas, gráficos, grabados y fotografías la hacen especialmente visual. Esa cantidad de ilustraciones, muchas a todo color, y el buen gramaje del papel engrosan el tomo, en una impresión que constituye un lujo para cualquier interesado en el Pacifico. Ediciones Doce Calles ha querido esmerarse con este primer título de una nueva colección, Pictura Mundi, dedicada a celebrar viajes, exploraciones y descubrimientos geográficos.

ENSAYO / Túlio Dias de Assis [Versión en inglés]

El presidente de Estados Unidos, Donald Trump, sorprendió en diciembre con otra de sus declaraciones, que al igual que muchas anteriores tampoco carecía de polémica. Esta vez el tema sorpresa fue el anuncio de la apertura de la embajada de EEUU en Jerusalén, consumando así el reconocimiento de la milenaria urbe como capital del único estado judío del mundo actual: Israel.

El polémico anuncio de Trump, en un asunto tan controvertido como delicado, fue criticado internacionalmente y tuvo escaso apoyo exterior. No obstante, algunos países –pocos– se sumaron a la iniciativa estadounidense, y algunos más se manifestaron con ambigüedad. Entre estos, diversos medios situaron a varios países de la Unión Europea. ¿Ha habido realmente falta de cohesión interna en la Unión sobre esta cuestión?

Por qué Jerusalén importa