Breadcrumb

Blogs

Entries with tag us border .

The Trump Administration’s Newest Migration Policies and Shifting Immigrant Demographics in the USA

New Trump administration migration policies including the "Safe Third Country" agreements signed by the USA, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras have reduced the number of migrants from the Northern Triangle countries at the southwest US border. As a consequence of this phenomenon and other factors, Mexicans have become once again the main national group of people deemed inadmissible for asylum or apprehended by the US Customs and Border Protection.

![An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov] An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov]](/documents/10174/16849987/migracion-mex-blog.jpg)

▲ An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov]

ARTICLE / Alexandria Casarano Christofellis

On March 31, 2018, the Trump administration cut off aid to the Northern Triangle countries in order to coerce them into implementing new policies to curb illegal migration to the United States. El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala all rely heavily on USAid, and had received 118, 181, and 257 million USD in USAid respectively in the 2017 fiscal year.

The US resumed financial aid to the Northern Triangle countries on October 17 of 2019, in the context of the establishment of bilateral negotiations of Safe Third Country agreements with each of the countries, and the implementation of the US Supreme Court’s de facto asylum ban on September 11 of 2019. The Safe Third Country agreements will allow the US to ‘return’ asylum seekers to the countries which they traveled through on their way to the US border (provided that the asylum seekers are not returned to their home countries). The US Supreme Court’s asylum ban similarly requires refugees to apply for and be denied asylum in each of the countries which they pass through before arriving at the US border to apply for asylum. This means that Honduran and Salvadoran refugees would need to apply for and be denied asylum in both Guatemala and Mexico before applying for asylum in the US, and Guatemalan refugees would need to apply for and be denied asylum in Mexico before applying for asylum in the US. This also means that refugees fleeing one of the Northern Triangle countries can be returned to another Northern Triangle country suffering many of the same issues they were fleeing in the first place.

Combined with the Trump administration’s longer-standing “metering” or “Remain in Mexico” policy (Migrant Protection Protocols/MPP), these political developments serve to effectively “push back” the US border. The “Remain in Mexico” policy requires US asylum seekers from Latin America to remain on the Mexican side of the US-Mexico border to wait their turn to be accepted into US territory. Within the past year, the US government has planted significant obstacles in the way of the path of Central American refugees to US asylum, and for better or worse has shifted the burden of the Central American refugee crisis to Mexico and the Central American countries themselves, which are ill-prepared to handle the influx, even in the light of resumed US foreign aid. The new arrangements resemble the EU’s refugee deal with Turkey.

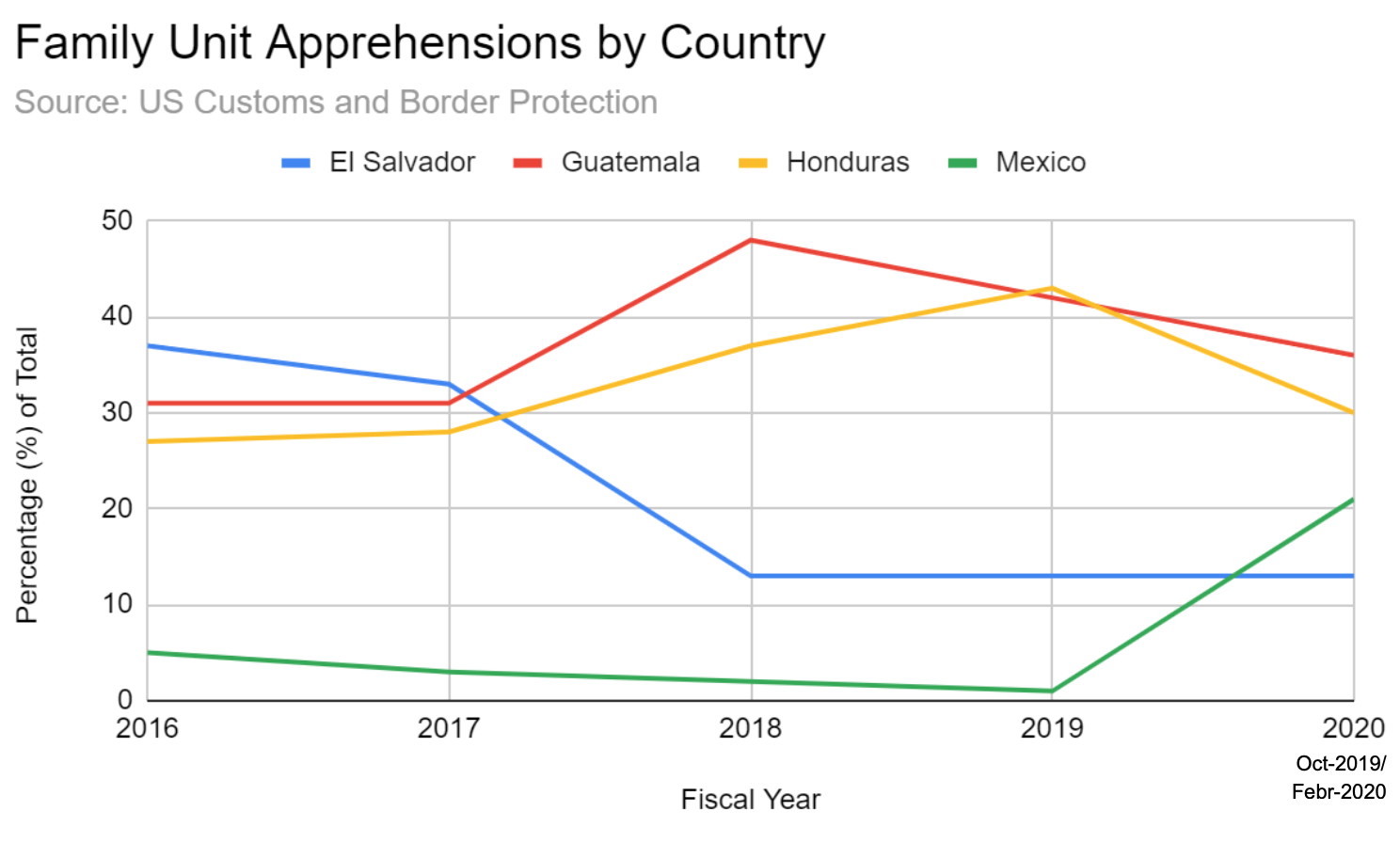

These policy changes are coupled with a shift in US immigration demographics. In August of 2019, Mexico reclaimed its position as the single largest source of unauthorized immigration to the US, having been temporarily surpassed by Guatemala and Honduras in 2018.

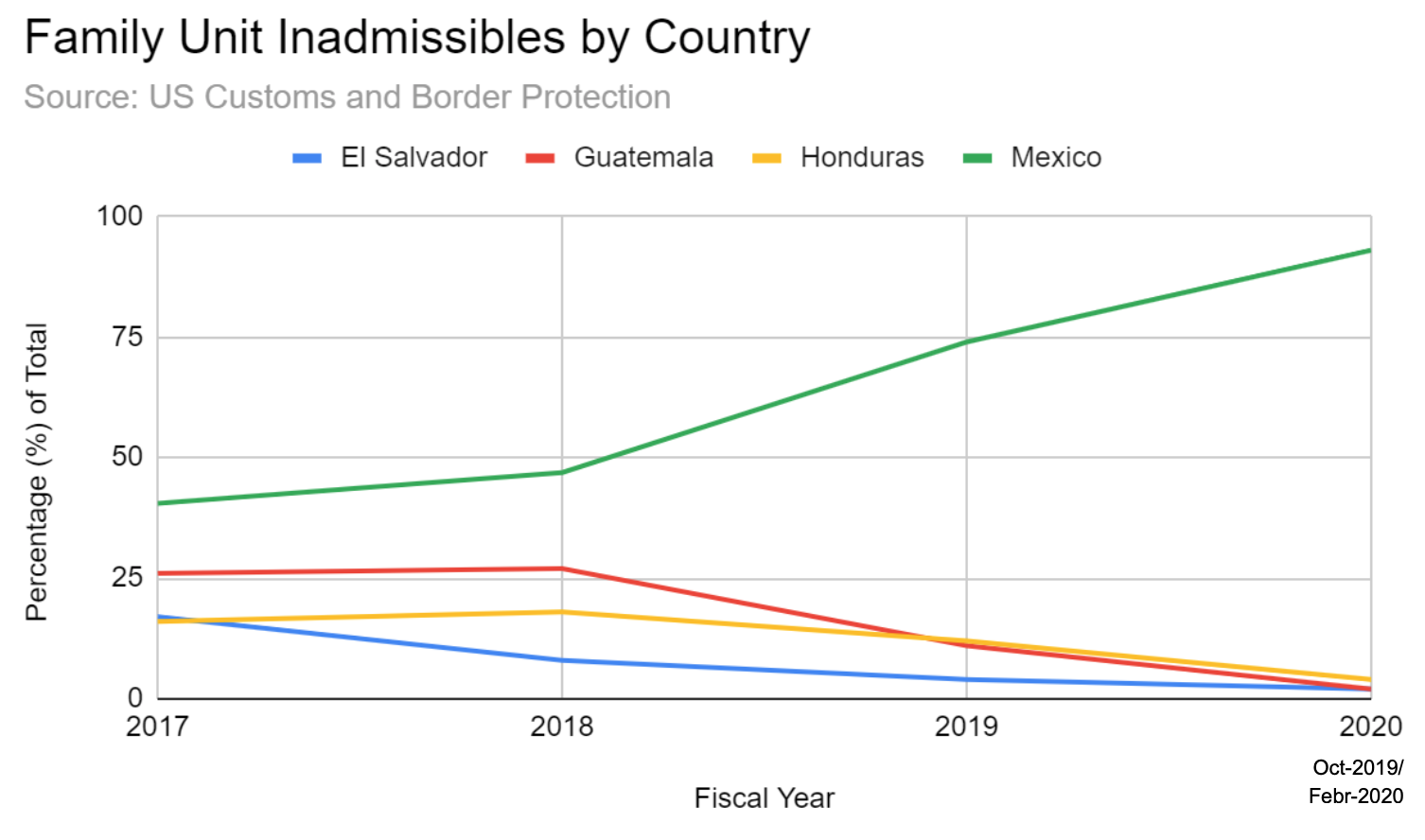

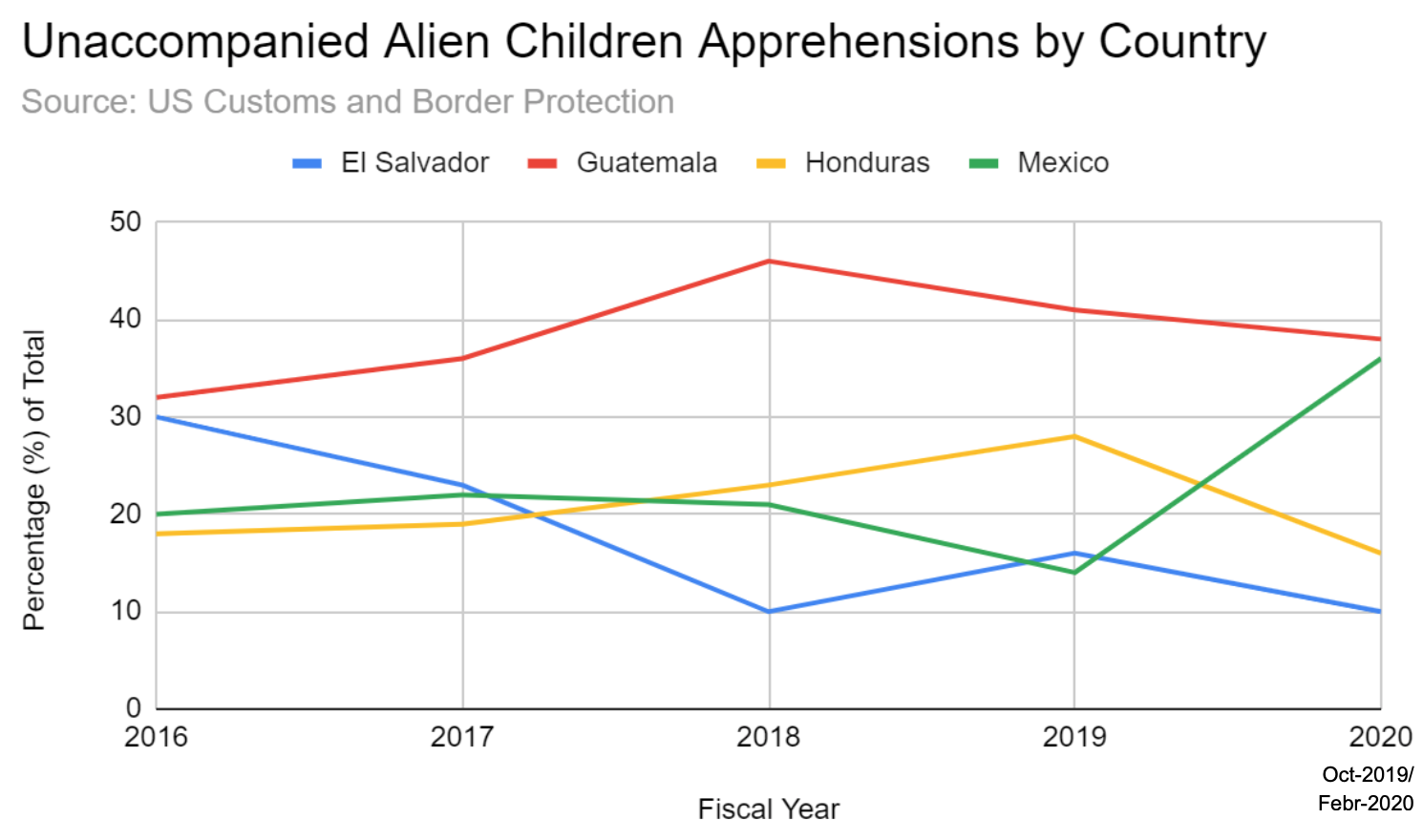

US Customs and Border Protection data indicates a net increase of 21% in the number of Unaccompanied Alien Children from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador deemed inadmissible for asylum at the Southwest US Border by the US field office between fiscal year 2019 (through February) and fiscal year 2020 (through February). All other inadmissible groups (Family Units, Single Adults, etc.) experienced a net decrease of 18-24% over the same time period. For both the entirety of fiscal year 2019 and fiscal year 2020 through February, Mexicans accounted for 69 and 61% of Unaccompanied Alien Children Inadmisibles at the Southwest US border respectively, whereas previously in fiscal years 2017 and 2018 Mexicans accounted for only 21 and 26% of these same figures, respectively. The percentages of Family Unit Inadmisibles from the Northern Triangle countries have been decreasing since 2018, while the percentage of Family Unit Inadmisibles from Mexico since 2018 has been on the rise.

With asylum made far less accessible to Central Americans in the wake of the Trump administration's new migration policies, the number of Central American inadmisibles is in sharp decline. Conversely, the number of Mexican inadmisibles is on the rise, having nearly tripled over the past three years.

Chain migration factors at play in Mexico may be contributing to this demographic shift. On September 10, 2019, prominent Mexican newspaper El Debate published an article titled “Immigrants Can Avoid Deportation with these Five Documents.” Additionally, The Washington Post cites the testimony of a city official from Michoacan, Mexico, claiming that a local Mexican travel company has begun running a weekly “door-to-door” service line to several US border points of entry, and that hundreds of Mexican citizens have been coming to the municipal offices daily requesting documentation to help them apply for asylum in the US. Word of mouth, press coverage like that found in El Debate, and the commercial exploitation of the Mexican migrant situation have perhaps made migration, and especially the claiming of asylum, more accessible to the Mexican population.

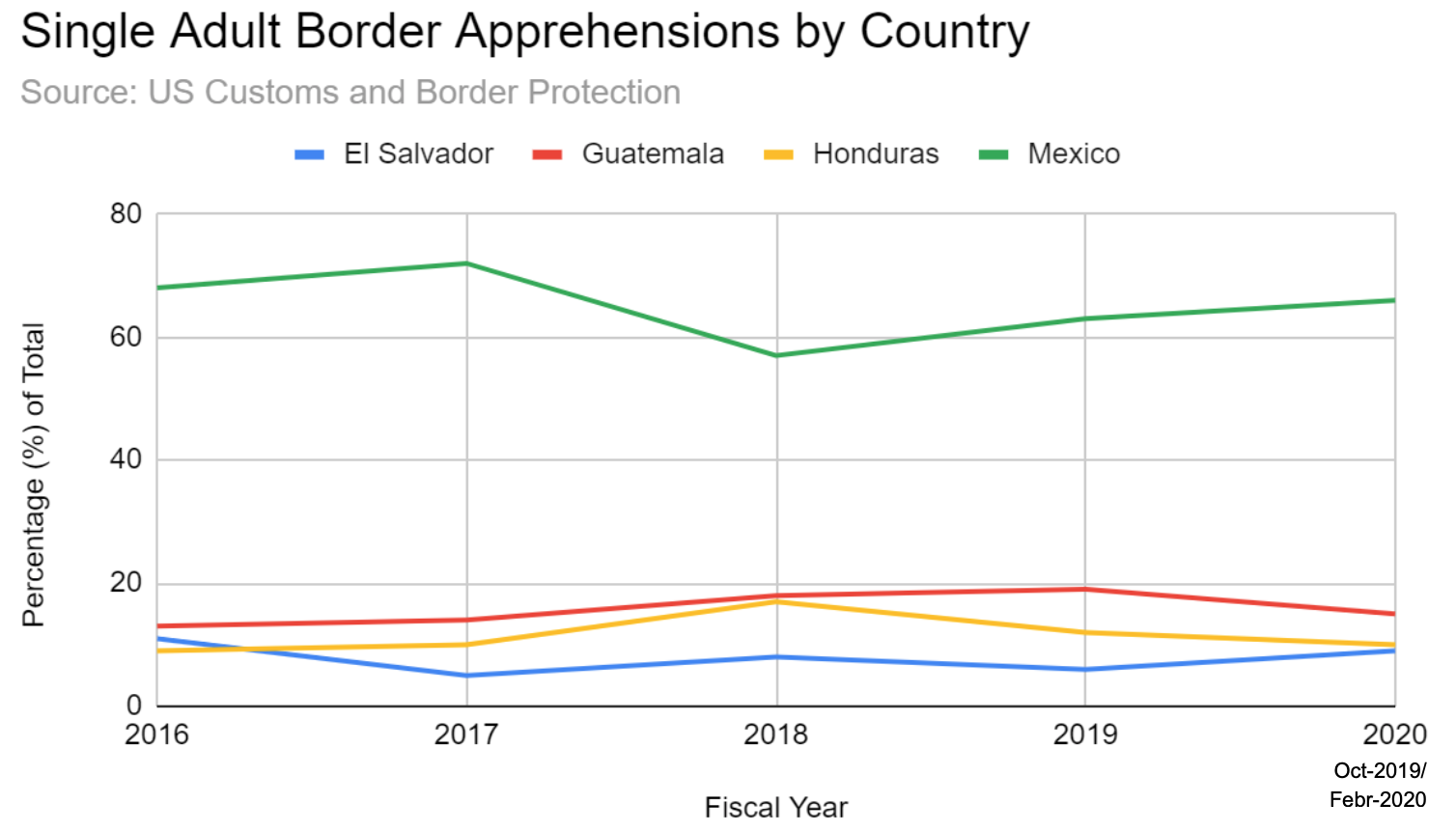

US Customs and Border Protection data also indicates that total apprehensions of migrants from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador attempting illegal crossings at the Southwest US border declined 44% for Unaccompanied Alien Children and 73% for Family Units between fiscal year 2019 (through February) and fiscal year 2020 (through February), while increasing for Single Adults by 4%. The same data trends show that while Mexicans have consistently accounted for the overwhelming majority of Single Adult Apprehensions since 2016, Family Unit and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions until the past year were dominated by Central Americans. However, in fiscal year 2020-February, the percentages of Central American Family Unit and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions have declined while the Mexican percentage has increased significantly. This could be attributed to the Northern Triangle countries’ and especially Mexico’s recent crackdown on the flow of illegal immigration within their own states in response to the same US sanctions and suspension of USAid which led to the Safe Third Country bilateral agreements with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

While the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigration from the Northern Triangle countries has effectively worked to limit both the legal and illegal access of Central Americans to US entry, the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigration from Mexico in the past few years has focused on arresting and deporting illegal Mexican immigrants already living and working within the US borders. Between 2017 and 2018, ICE increased workplace raids to arrest undocumented immigrants by over 400% according to The Independent in the UK. The trend seemed to continue into 2019. President Trump tweeted on June 17, 2019 that “Next week ICE will begin the process of removing the millions of illegal aliens who have illicitly found their way into the United States. They will be removed as fast as they come in.” More deportations could be leading to more attempts at reentry, increasing Mexican migration to the US, and more Mexican Single Adult apprehensions at the Southwest border. The Washington Post alleges that the majority of the Mexican single adults apprehended at the border are previous deportees trying to reenter the country.

Lastly, the steadily increasing violence within the state of Mexico should not be overlooked as a cause for continued migration. Within the past year, violence between the various Mexican cartels has intensified, and murder rates have continued to rise. While the increase in violence alone is not intense enough to solely account for the spike that has recently been seen in Mexican migration to the US, internal violence nethertheless remains an important factor in the Mexican migrant situation. Similarly, widespread poverty in Mexico, recently worsened by a decline in foreign investment in the light of threatened tariffs from the USA, also plays a key role.

In conclusion, the Trump administration’s new migration policies mark an intensification of long-standing nativist tendencies in the US, and pose a potential threat to the human rights of asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border. The corresponding present demographic shift back to Mexican predominance in US immigration is driven not only by the Trump administration’s new migration policies, but also by many other diverse factors within both Mexico and the US, from press coverage to increased deportations to long-standing cartel violence and poverty. In the face of these recent developments, one thing remains clear: the situation south of the Rio Grande is just as complex, nuanced, and constantly evolving as is the situation to the north on Capitol Hill in the USA.

![US border patrol vehicle near the fence with Mexico [Wikimedia Commons] US border patrol vehicle near the fence with Mexico [Wikimedia Commons]](/documents/10174/16849987/us-border-blog.jpg)

▲ US border patrol vehicle near the fence with Mexico [Wikimedia Commons]

ESSAY / Gabriel de Lange

I. Current issues in the Northern Triangle

In recent years, the relationship between the Northern Triangle Countries (NTC) –Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador– and it’s northern neighbours Mexico and the United States has been marked in mainstream media for their surging migration patterns. As of 2019, a total of 977,509 individuals have been apprehended at the Southwest border of the US (the border with Mexico) as compared to 521,093 the previous year (years in terms of US fiscal years). Of this number, an estimated 75% have come from the NTC[1]. These individuals are typically divided into three categories: single adults, family units, and unaccompanied alien children (UAC).

As the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) reports, over 65% of the population of the NTC are below 29 years of age[2]. This is why it is rather alarming to see an increasing number of the youth population from these countries leaving their homes and becoming UAC at the border.

Why are these youths migrating? Many studies normally associate this to “push factors.” The first factor being an increase in insecurity and violence, particularly from transnational organised crime, gangs, and narco-trafficking[3]. It is calculated that six children flee to the US for every ten homicides in the Northern Triangle[4]. The second significant factor is weak governance and corruption; this undermines public trust in the system, worsens the effects of criminal activity, and diverts funds meant to improve infrastructure and social service systems. The third factor is poverty and lack of economic development; for example in Guatemala and Honduras, roughly 60% of people live below the poverty line[5].

The other perspective to explain migration is through what are called “pull factors.” An example would be the lure of economic possibilities abroad, like the high US demand for low-skilled workers, a service that citizens of NTC can provide and be better paid for that in their home countries. Another pull factor worth mentioning is lax immigration laws, if the consequences for illegal entry into a country are light, then individuals are more likely to migrate for the chance at attaining better work, educational, and healthcare opportunities[6].

II. US administrations’ strategies

A. The Obama administration (2008-2015)

The Obama administration for the most part used the carrot and soft power approach in its engagement with the NTC. Its main goals in the region being to “improve security, strengthen governance, and promote economic prosperity in the region”, it saw these developments in the NTC as being in the best interest of US national security[7].

In 2014, in the wake of the massive surge of migrants, specially UACs, the administration launched the reform initiative titled the Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity (A4P). The plan expanded across Central America but with special focus on the NTC. This was a five year plan to address these “push factors” that cause people to migrate. The four main ways that the initiative aims to accomplish this is by promoting the following: first, by fostering the productivity sector to address the region’s economic instability; second, by developing human capital to increase the quality of life, which improves education, healthcare and social services; third, improving citizen security and access to justices to address the insecurity and violence threat, and lastly, strengthening institutions and improving transparency to address the concerns for weak governance and corruption[8].

This initiative would receive direct technical support and financing from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). In addition, major funding was to be provided by the US, which for the fiscal years of 2015-2018 committed $2.6 billion split for bilateral assistance, Regional Security Strategy (RSS), and other regional services[9]. The NTC governments themselves were major financiers of the initiative, committing approximately $8.6 billion between 2016-2018[10].

The administration even launched programs with the US Agency for International Development (USAID). The principle one being the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), with a heavy focus on the NTC and it’s security issues, which allotted a budget of $1.2 billion in 2008. This would later evolve into the larger framework of US Strategy for Engagement in Central America in 2016.

The Obama administration also launched in 2015 the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which currently allows individuals who were brought to the US as children, and have unlawful statuses to receive a renewable two-year period of deferred action from deportation[11]. It is a policy that the Trump administration has been fighting to remove these last few years.

Although the Obama administration was quite diplomatic and optimistic in its approach, that didn’t mean it didn’t make efforts to lessen the migration factors in more aggressive ways too. In fact, the administration reportedly deported over three million illegal immigrants through the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the highest amount of deportations taking place in the fiscal year of 2012 reaching 409,849 which was higher than any single one of the Trump administration’s reported fiscal years to date[12].

In addition, the Obama administration used educational campaigns to discourage individuals from trying to cross into the US illegally. In 2014 they also launched a Central American Minors (CAM) camp targeting children from the NTC and providing a “safe, legal and orderly alternative to US migration”[13]. This however was later scrapped by the Trump Administration, along with any sense of reassessment brought about by Obama’s carrot approach.

![Number of apprehensions and inadmissibles on the US border with Mexico [Source: CBP] Number of apprehensions and inadmissibles on the US border with Mexico [Source: CBP]](/documents/10174/16849987/us-border-grafico.png)

Number of apprehensions and inadmissibles on the US border with Mexico [Source: CBP]

B. The Trump administration (2016-present)

The Trump administration’s strategy in the region has undoubtedly gone with the stick approach. The infamous “zero tolerance policy” which took place from April-June 2018 is a testimony to this idea, resulting in the separation of thousands of children from their parents and being reclassified as UAC[14]. This was in an attempt to discourage individuals in the NTC from illegally entering the US and address these lax immigration laws.

From early on Trump campaigned based on the idea of placing America’s interests first, and as a result has reevaluated many international treaties and policies. In 2016 the administration proposed scaling back funds for the NTC through the A4P, however this was blocked in Congress and the funds went through albeit in a decreasing value starting with $754 million in 2016 to only $535 million in 2019.

Another significant difference between the two administrations is that while Obama’s focused on large multi-lateral initiatives like the A4P, the Trump administration has elected to focus on a more bilateral approach, one that goes back and forth between cooperation and threats, to compliment the existing strategy.

Towards the end of 2018 the US and Mexico had announced the concept of a “Marshal Plan” for Central America with both countries proposing large sums of money to be given annually to help improve the economic and security conditions in the NTC. However in this last year it has become more apparent that there will be difficulties raising funds, especially due to their reliance on private investment organisations and lack of executive cooperation. Just last May, Trump threatened to place tariffs on Mexico due to its inability to decrease immigration flow. President López Obrador responded by deploying the National Guard to Mexico’s border with Guatemala, resulting in a decrease of border apprehensions by 56%[15] on the US Southwest border. This shows that the stick method can achieve results, but that real cooperation can not be achieved if leaders don’t see eye to eye and follow through on commitments. If large amount of funding where to be put in vague unclear programs and goals in the NTC, it is likely to end up in the wrong hands due to corruption[16].

In terms of bilateral agreements with NTC countries, Trump has been successful in negotiation with Guatemala and Honduras in signing asylum cooperative agreements, which has many similarities with a safe third country agreement, though not exactly worded as such. Trump struck a similar deal with El Salvador, though sweetened it by granting a solution for over 200,000 Salvadorans living in US under a Temporary Protection Status (TPS).[17]

However, Trump has not been the only interested party in the NTC and Mexico. The United Nations’ ECLAC launched last year its “El Salvador-Guatemala-Honduras-Mexico Comprehensive Development Program”, which aims to target the root causes of migration in the NTC. It does this by promoting policies that relate to the UN 2030 agenda and the 17 sustainable development goals. The four pillars of this initiative being: economic development, social well-being, environmental sustainability, and comprehensive management of migratory patters[18]. However the financing behind this initiative remains ambiguous and the goals behind it seem redundant. They reflect the same goals established by the A4P, just simply under a different entity.

The main difference between the Obama and Trump administrations is that the A4P takes a slow approach aiming to address the fundamental issues triggering migration patterns, the results of which will likely take 10-15 years and steady multi-lateral investment to see real progress. Meanwhile the Trump administration aims to get quick results by creating bilateral agreements with these NTC in order to distribute the negative effects of migration among them and lifting the immediate burden. Separately, neither strategy appears wholesome and convincing enough to rally congressional and public support. However, the combination of all initiatives –investing effort both in the long and short run, along with additional initiatives like ECLAC’s program to reinforce the region’s goals– could perhaps be the most effective mechanism to combat insecurity, weak governance, and economic hardships in the NTC.

[1] Nowrasteh, Alex. “1.3 Percent of All Central Americans in the Northern Triangle Were Apprehended by Border Patrol This Fiscal Year - So Far”. Cato at Library. June 7, 2019. Accessed November 8, 2019.

[2] N/A. “Triángulo Norte: Construyendo Confianza, Creando Oportunidades.” Inter-American Development Bank. Accessed November 5, 2019.

[3] Orozco, Manuel. “Central American Migration: Current Changes and Development Implications.” The Dialogue. November 2018. Accessed November 2019.

[4] Bell, Caroline. “Where is the Northern Triangle?” The Borgen Project. October 23, 2019. Accessed November 6, 2019.

[5] Cheatham, Amelia. “Central America’s Turbulent Northern Triangle.” Council on Foreign Relations. October 1, 2019. Accessed November 6, 2019.

[6] Arthur, R. Andrew. “Unaccompanied Alien Children and the Crisis at the Border.” Center for Immigration Studies. April 1, 2019. Accessed November 9, 2019.

[7] Members and Committees of Congress. “U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: Policy Issues for Congress.” Congressional Research Service. Updated November 12, 2019. November 13, 2019.

[8] N/A. “Strategic Pillars and Lines of Action.” Inter-American Development Bank. 2019. Accessed November 10, 2019.

[9] N/A. “Budgetary Resources Allocated for the Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity.” Inter-American Development Bank. N/A. Accessed November 10, 2019.

[10] Schneider, L. Mark. Matera, A. Michael. “Where Are the Northern Triangle Countries Headed? And What Is U.S. Policy?” Centre for Strategic and International Studies. August 20, 2019. Accessed November 11, 2019.

[11] N/A. “Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA).” Department of Homeland Security. N/A. Accessed November 12, 2019.

[12] Kight, W. Stef. Treene, Alayna. “Trump isn’t Matching Obama deportation numbers.” Axios. June 21, 2019. Accessed November 13, 2019.

[13] N/A. “Unaccompanied Alien Children: An Overview.” Congressional Research Service. October 9, 2019. Accessed November 10, 2019.

[14] N/A. “Unaccompanied Alien Children: An Overview.” Congressional Research Service. October 9, 2019. Accessed November 10, 2019.

[15] Nagovitch, Paola. “Explainer: U.S. Immigration Deals with Northern Triangle Countries and Mexico.” American Society/Council of Americans. October 3, 2019. Accessed November 10, 2019.

[16] Berg, C. Ryan. “A Central American Martial Plan Won’t Work.” Foreign Policy. March 5, 2019. Accessed November 11, 2019.

[17] Nagovitch, Paola. “Explainer: U.S. Immigration Deals with Northern Triangle Countries and Mexico.” American Society/Council of Americans. October 3, 2019. Accessed November 10, 2019.

[18] Press Release. “El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Mexico Reaffirm their Commitment to the Comprehensive Development Plan.” ECLAC. September 19,2019. Accessed November 11, 2019.