Breadcrumb

Blogs

Entries with tag northern triangle .

The Trump Administration’s Newest Migration Policies and Shifting Immigrant Demographics in the USA

New Trump administration migration policies including the "Safe Third Country" agreements signed by the USA, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras have reduced the number of migrants from the Northern Triangle countries at the southwest US border. As a consequence of this phenomenon and other factors, Mexicans have become once again the main national group of people deemed inadmissible for asylum or apprehended by the US Customs and Border Protection.

![An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov] An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov]](/documents/10174/16849987/migracion-mex-blog.jpg)

▲ An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov]

ARTICLE / Alexandria Casarano Christofellis

On March 31, 2018, the Trump administration cut off aid to the Northern Triangle countries in order to coerce them into implementing new policies to curb illegal migration to the United States. El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala all rely heavily on USAid, and had received 118, 181, and 257 million USD in USAid respectively in the 2017 fiscal year.

The US resumed financial aid to the Northern Triangle countries on October 17 of 2019, in the context of the establishment of bilateral negotiations of Safe Third Country agreements with each of the countries, and the implementation of the US Supreme Court’s de facto asylum ban on September 11 of 2019. The Safe Third Country agreements will allow the US to ‘return’ asylum seekers to the countries which they traveled through on their way to the US border (provided that the asylum seekers are not returned to their home countries). The US Supreme Court’s asylum ban similarly requires refugees to apply for and be denied asylum in each of the countries which they pass through before arriving at the US border to apply for asylum. This means that Honduran and Salvadoran refugees would need to apply for and be denied asylum in both Guatemala and Mexico before applying for asylum in the US, and Guatemalan refugees would need to apply for and be denied asylum in Mexico before applying for asylum in the US. This also means that refugees fleeing one of the Northern Triangle countries can be returned to another Northern Triangle country suffering many of the same issues they were fleeing in the first place.

Combined with the Trump administration’s longer-standing “metering” or “Remain in Mexico” policy (Migrant Protection Protocols/MPP), these political developments serve to effectively “push back” the US border. The “Remain in Mexico” policy requires US asylum seekers from Latin America to remain on the Mexican side of the US-Mexico border to wait their turn to be accepted into US territory. Within the past year, the US government has planted significant obstacles in the way of the path of Central American refugees to US asylum, and for better or worse has shifted the burden of the Central American refugee crisis to Mexico and the Central American countries themselves, which are ill-prepared to handle the influx, even in the light of resumed US foreign aid. The new arrangements resemble the EU’s refugee deal with Turkey.

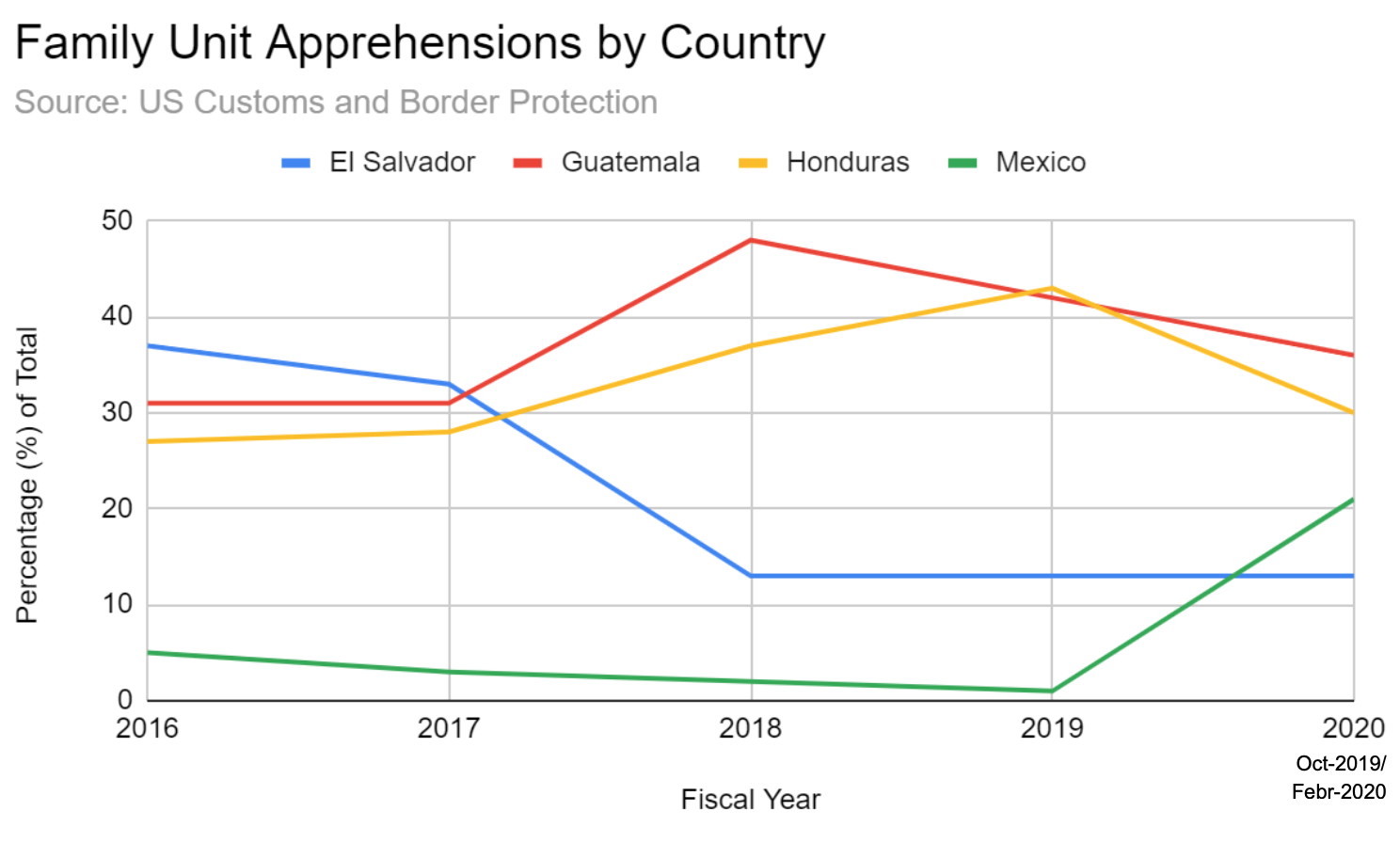

These policy changes are coupled with a shift in US immigration demographics. In August of 2019, Mexico reclaimed its position as the single largest source of unauthorized immigration to the US, having been temporarily surpassed by Guatemala and Honduras in 2018.

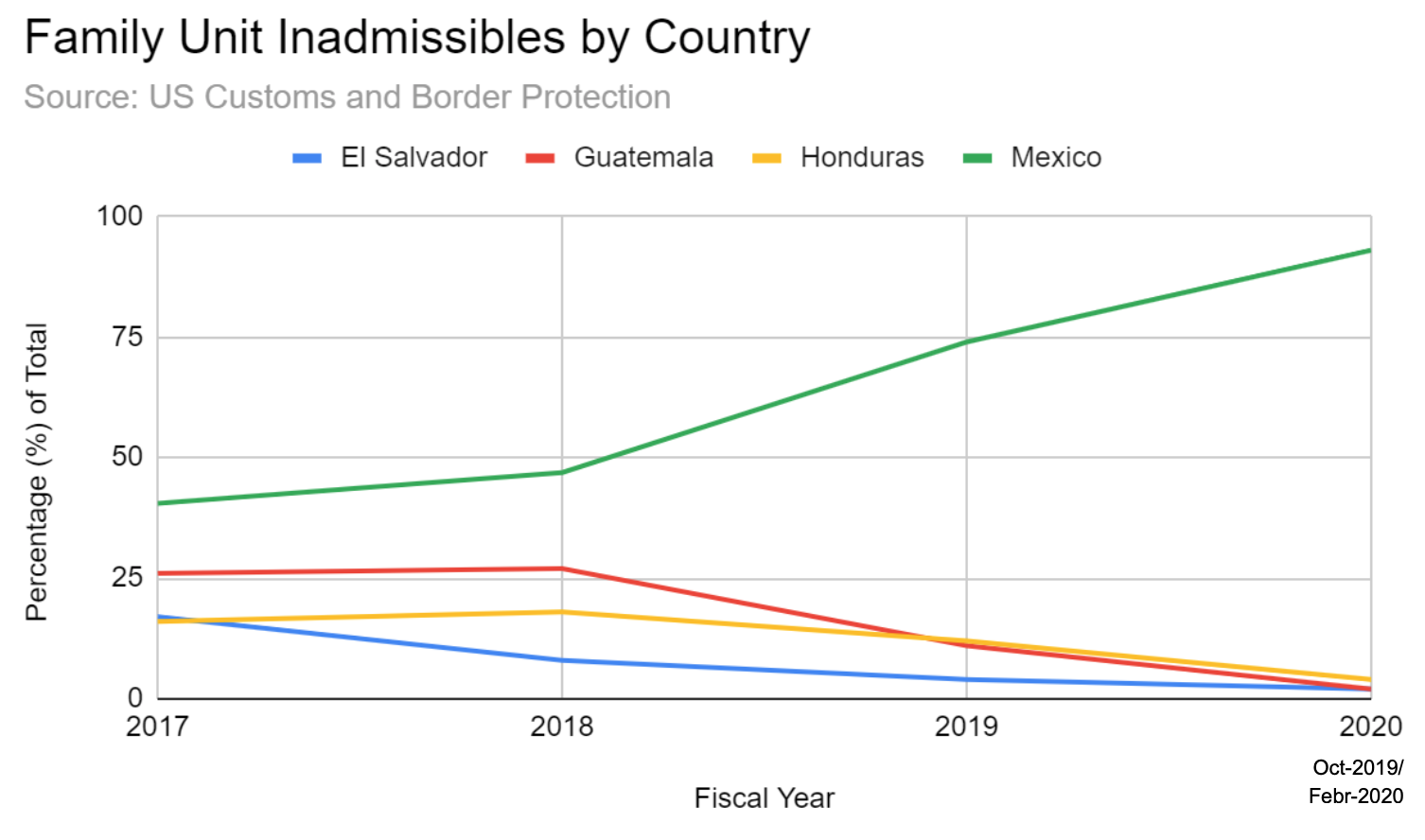

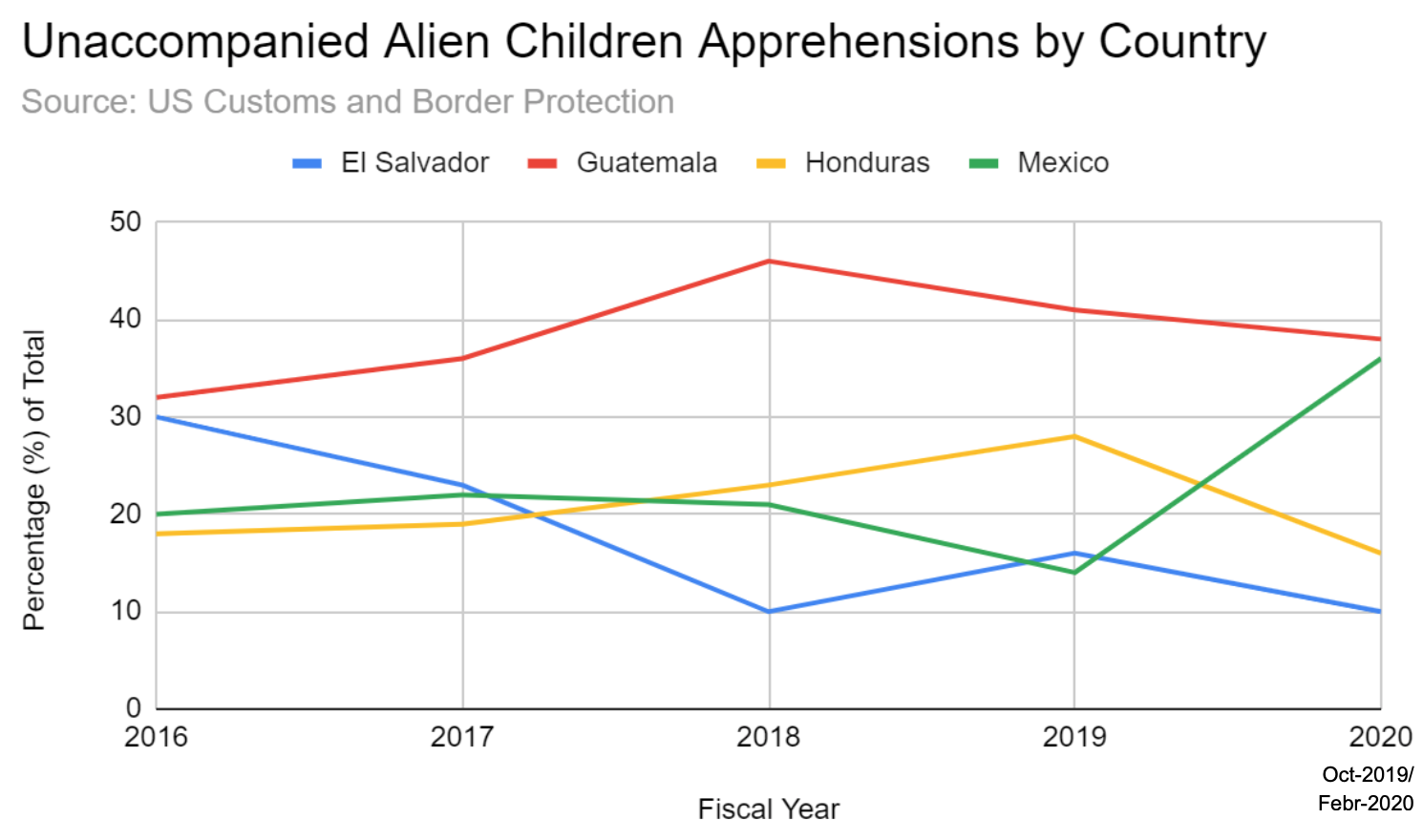

US Customs and Border Protection data indicates a net increase of 21% in the number of Unaccompanied Alien Children from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador deemed inadmissible for asylum at the Southwest US Border by the US field office between fiscal year 2019 (through February) and fiscal year 2020 (through February). All other inadmissible groups (Family Units, Single Adults, etc.) experienced a net decrease of 18-24% over the same time period. For both the entirety of fiscal year 2019 and fiscal year 2020 through February, Mexicans accounted for 69 and 61% of Unaccompanied Alien Children Inadmisibles at the Southwest US border respectively, whereas previously in fiscal years 2017 and 2018 Mexicans accounted for only 21 and 26% of these same figures, respectively. The percentages of Family Unit Inadmisibles from the Northern Triangle countries have been decreasing since 2018, while the percentage of Family Unit Inadmisibles from Mexico since 2018 has been on the rise.

With asylum made far less accessible to Central Americans in the wake of the Trump administration's new migration policies, the number of Central American inadmisibles is in sharp decline. Conversely, the number of Mexican inadmisibles is on the rise, having nearly tripled over the past three years.

Chain migration factors at play in Mexico may be contributing to this demographic shift. On September 10, 2019, prominent Mexican newspaper El Debate published an article titled “Immigrants Can Avoid Deportation with these Five Documents.” Additionally, The Washington Post cites the testimony of a city official from Michoacan, Mexico, claiming that a local Mexican travel company has begun running a weekly “door-to-door” service line to several US border points of entry, and that hundreds of Mexican citizens have been coming to the municipal offices daily requesting documentation to help them apply for asylum in the US. Word of mouth, press coverage like that found in El Debate, and the commercial exploitation of the Mexican migrant situation have perhaps made migration, and especially the claiming of asylum, more accessible to the Mexican population.

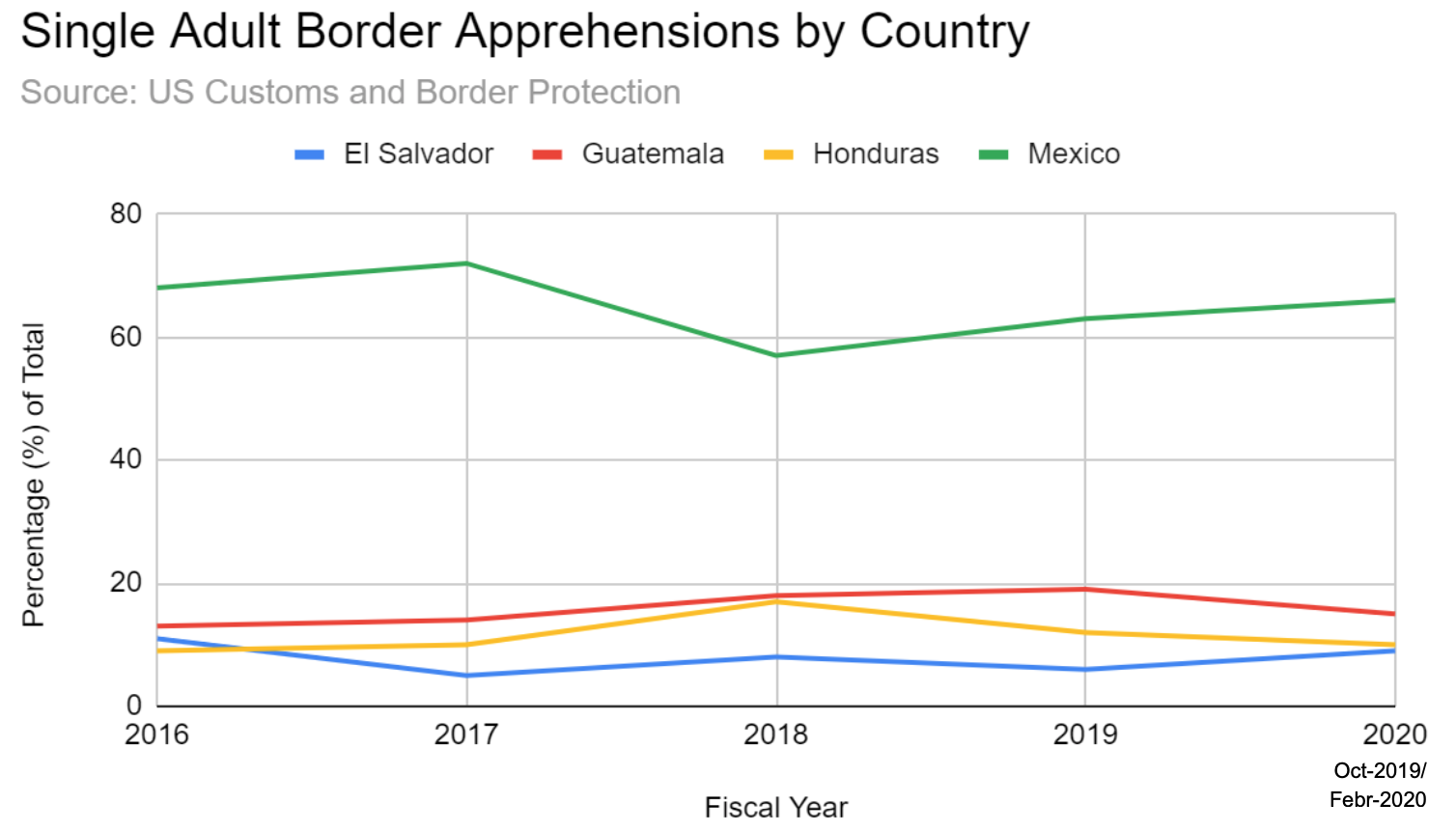

US Customs and Border Protection data also indicates that total apprehensions of migrants from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador attempting illegal crossings at the Southwest US border declined 44% for Unaccompanied Alien Children and 73% for Family Units between fiscal year 2019 (through February) and fiscal year 2020 (through February), while increasing for Single Adults by 4%. The same data trends show that while Mexicans have consistently accounted for the overwhelming majority of Single Adult Apprehensions since 2016, Family Unit and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions until the past year were dominated by Central Americans. However, in fiscal year 2020-February, the percentages of Central American Family Unit and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions have declined while the Mexican percentage has increased significantly. This could be attributed to the Northern Triangle countries’ and especially Mexico’s recent crackdown on the flow of illegal immigration within their own states in response to the same US sanctions and suspension of USAid which led to the Safe Third Country bilateral agreements with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

While the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigration from the Northern Triangle countries has effectively worked to limit both the legal and illegal access of Central Americans to US entry, the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigration from Mexico in the past few years has focused on arresting and deporting illegal Mexican immigrants already living and working within the US borders. Between 2017 and 2018, ICE increased workplace raids to arrest undocumented immigrants by over 400% according to The Independent in the UK. The trend seemed to continue into 2019. President Trump tweeted on June 17, 2019 that “Next week ICE will begin the process of removing the millions of illegal aliens who have illicitly found their way into the United States. They will be removed as fast as they come in.” More deportations could be leading to more attempts at reentry, increasing Mexican migration to the US, and more Mexican Single Adult apprehensions at the Southwest border. The Washington Post alleges that the majority of the Mexican single adults apprehended at the border are previous deportees trying to reenter the country.

Lastly, the steadily increasing violence within the state of Mexico should not be overlooked as a cause for continued migration. Within the past year, violence between the various Mexican cartels has intensified, and murder rates have continued to rise. While the increase in violence alone is not intense enough to solely account for the spike that has recently been seen in Mexican migration to the US, internal violence nethertheless remains an important factor in the Mexican migrant situation. Similarly, widespread poverty in Mexico, recently worsened by a decline in foreign investment in the light of threatened tariffs from the USA, also plays a key role.

In conclusion, the Trump administration’s new migration policies mark an intensification of long-standing nativist tendencies in the US, and pose a potential threat to the human rights of asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border. The corresponding present demographic shift back to Mexican predominance in US immigration is driven not only by the Trump administration’s new migration policies, but also by many other diverse factors within both Mexico and the US, from press coverage to increased deportations to long-standing cartel violence and poverty. In the face of these recent developments, one thing remains clear: the situation south of the Rio Grande is just as complex, nuanced, and constantly evolving as is the situation to the north on Capitol Hill in the USA.

![US border patrol vehicle near the fence with Mexico [Wikimedia Commons] US border patrol vehicle near the fence with Mexico [Wikimedia Commons]](/documents/10174/16849987/us-border-blog.jpg)

▲ US border patrol vehicle near the fence with Mexico [Wikimedia Commons]

ESSAY / Gabriel de Lange

I. Current issues in the Northern Triangle

In recent years, the relationship between the Northern Triangle Countries (NTC) –Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador– and it’s northern neighbours Mexico and the United States has been marked in mainstream media for their surging migration patterns. As of 2019, a total of 977,509 individuals have been apprehended at the Southwest border of the US (the border with Mexico) as compared to 521,093 the previous year (years in terms of US fiscal years). Of this number, an estimated 75% have come from the NTC[1]. These individuals are typically divided into three categories: single adults, family units, and unaccompanied alien children (UAC).

As the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) reports, over 65% of the population of the NTC are below 29 years of age[2]. This is why it is rather alarming to see an increasing number of the youth population from these countries leaving their homes and becoming UAC at the border.

Why are these youths migrating? Many studies normally associate this to “push factors.” The first factor being an increase in insecurity and violence, particularly from transnational organised crime, gangs, and narco-trafficking[3]. It is calculated that six children flee to the US for every ten homicides in the Northern Triangle[4]. The second significant factor is weak governance and corruption; this undermines public trust in the system, worsens the effects of criminal activity, and diverts funds meant to improve infrastructure and social service systems. The third factor is poverty and lack of economic development; for example in Guatemala and Honduras, roughly 60% of people live below the poverty line[5].

The other perspective to explain migration is through what are called “pull factors.” An example would be the lure of economic possibilities abroad, like the high US demand for low-skilled workers, a service that citizens of NTC can provide and be better paid for that in their home countries. Another pull factor worth mentioning is lax immigration laws, if the consequences for illegal entry into a country are light, then individuals are more likely to migrate for the chance at attaining better work, educational, and healthcare opportunities[6].

II. US administrations’ strategies

A. The Obama administration (2008-2015)

The Obama administration for the most part used the carrot and soft power approach in its engagement with the NTC. Its main goals in the region being to “improve security, strengthen governance, and promote economic prosperity in the region”, it saw these developments in the NTC as being in the best interest of US national security[7].

In 2014, in the wake of the massive surge of migrants, specially UACs, the administration launched the reform initiative titled the Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity (A4P). The plan expanded across Central America but with special focus on the NTC. This was a five year plan to address these “push factors” that cause people to migrate. The four main ways that the initiative aims to accomplish this is by promoting the following: first, by fostering the productivity sector to address the region’s economic instability; second, by developing human capital to increase the quality of life, which improves education, healthcare and social services; third, improving citizen security and access to justices to address the insecurity and violence threat, and lastly, strengthening institutions and improving transparency to address the concerns for weak governance and corruption[8].

This initiative would receive direct technical support and financing from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). In addition, major funding was to be provided by the US, which for the fiscal years of 2015-2018 committed $2.6 billion split for bilateral assistance, Regional Security Strategy (RSS), and other regional services[9]. The NTC governments themselves were major financiers of the initiative, committing approximately $8.6 billion between 2016-2018[10].

The administration even launched programs with the US Agency for International Development (USAID). The principle one being the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), with a heavy focus on the NTC and it’s security issues, which allotted a budget of $1.2 billion in 2008. This would later evolve into the larger framework of US Strategy for Engagement in Central America in 2016.

The Obama administration also launched in 2015 the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which currently allows individuals who were brought to the US as children, and have unlawful statuses to receive a renewable two-year period of deferred action from deportation[11]. It is a policy that the Trump administration has been fighting to remove these last few years.

Although the Obama administration was quite diplomatic and optimistic in its approach, that didn’t mean it didn’t make efforts to lessen the migration factors in more aggressive ways too. In fact, the administration reportedly deported over three million illegal immigrants through the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the highest amount of deportations taking place in the fiscal year of 2012 reaching 409,849 which was higher than any single one of the Trump administration’s reported fiscal years to date[12].

In addition, the Obama administration used educational campaigns to discourage individuals from trying to cross into the US illegally. In 2014 they also launched a Central American Minors (CAM) camp targeting children from the NTC and providing a “safe, legal and orderly alternative to US migration”[13]. This however was later scrapped by the Trump Administration, along with any sense of reassessment brought about by Obama’s carrot approach.

![Number of apprehensions and inadmissibles on the US border with Mexico [Source: CBP] Number of apprehensions and inadmissibles on the US border with Mexico [Source: CBP]](/documents/10174/16849987/us-border-grafico.png)

Number of apprehensions and inadmissibles on the US border with Mexico [Source: CBP]

B. The Trump administration (2016-present)

The Trump administration’s strategy in the region has undoubtedly gone with the stick approach. The infamous “zero tolerance policy” which took place from April-June 2018 is a testimony to this idea, resulting in the separation of thousands of children from their parents and being reclassified as UAC[14]. This was in an attempt to discourage individuals in the NTC from illegally entering the US and address these lax immigration laws.

From early on Trump campaigned based on the idea of placing America’s interests first, and as a result has reevaluated many international treaties and policies. In 2016 the administration proposed scaling back funds for the NTC through the A4P, however this was blocked in Congress and the funds went through albeit in a decreasing value starting with $754 million in 2016 to only $535 million in 2019.

Another significant difference between the two administrations is that while Obama’s focused on large multi-lateral initiatives like the A4P, the Trump administration has elected to focus on a more bilateral approach, one that goes back and forth between cooperation and threats, to compliment the existing strategy.

Towards the end of 2018 the US and Mexico had announced the concept of a “Marshal Plan” for Central America with both countries proposing large sums of money to be given annually to help improve the economic and security conditions in the NTC. However in this last year it has become more apparent that there will be difficulties raising funds, especially due to their reliance on private investment organisations and lack of executive cooperation. Just last May, Trump threatened to place tariffs on Mexico due to its inability to decrease immigration flow. President López Obrador responded by deploying the National Guard to Mexico’s border with Guatemala, resulting in a decrease of border apprehensions by 56%[15] on the US Southwest border. This shows that the stick method can achieve results, but that real cooperation can not be achieved if leaders don’t see eye to eye and follow through on commitments. If large amount of funding where to be put in vague unclear programs and goals in the NTC, it is likely to end up in the wrong hands due to corruption[16].

In terms of bilateral agreements with NTC countries, Trump has been successful in negotiation with Guatemala and Honduras in signing asylum cooperative agreements, which has many similarities with a safe third country agreement, though not exactly worded as such. Trump struck a similar deal with El Salvador, though sweetened it by granting a solution for over 200,000 Salvadorans living in US under a Temporary Protection Status (TPS).[17]

However, Trump has not been the only interested party in the NTC and Mexico. The United Nations’ ECLAC launched last year its “El Salvador-Guatemala-Honduras-Mexico Comprehensive Development Program”, which aims to target the root causes of migration in the NTC. It does this by promoting policies that relate to the UN 2030 agenda and the 17 sustainable development goals. The four pillars of this initiative being: economic development, social well-being, environmental sustainability, and comprehensive management of migratory patters[18]. However the financing behind this initiative remains ambiguous and the goals behind it seem redundant. They reflect the same goals established by the A4P, just simply under a different entity.

The main difference between the Obama and Trump administrations is that the A4P takes a slow approach aiming to address the fundamental issues triggering migration patterns, the results of which will likely take 10-15 years and steady multi-lateral investment to see real progress. Meanwhile the Trump administration aims to get quick results by creating bilateral agreements with these NTC in order to distribute the negative effects of migration among them and lifting the immediate burden. Separately, neither strategy appears wholesome and convincing enough to rally congressional and public support. However, the combination of all initiatives –investing effort both in the long and short run, along with additional initiatives like ECLAC’s program to reinforce the region’s goals– could perhaps be the most effective mechanism to combat insecurity, weak governance, and economic hardships in the NTC.

[1] Nowrasteh, Alex. “1.3 Percent of All Central Americans in the Northern Triangle Were Apprehended by Border Patrol This Fiscal Year - So Far”. Cato at Library. June 7, 2019. Accessed November 8, 2019.

[2] N/A. “Triángulo Norte: Construyendo Confianza, Creando Oportunidades.” Inter-American Development Bank. Accessed November 5, 2019.

[3] Orozco, Manuel. “Central American Migration: Current Changes and Development Implications.” The Dialogue. November 2018. Accessed November 2019.

[4] Bell, Caroline. “Where is the Northern Triangle?” The Borgen Project. October 23, 2019. Accessed November 6, 2019.

[5] Cheatham, Amelia. “Central America’s Turbulent Northern Triangle.” Council on Foreign Relations. October 1, 2019. Accessed November 6, 2019.

[6] Arthur, R. Andrew. “Unaccompanied Alien Children and the Crisis at the Border.” Center for Immigration Studies. April 1, 2019. Accessed November 9, 2019.

[7] Members and Committees of Congress. “U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: Policy Issues for Congress.” Congressional Research Service. Updated November 12, 2019. November 13, 2019.

[8] N/A. “Strategic Pillars and Lines of Action.” Inter-American Development Bank. 2019. Accessed November 10, 2019.

[9] N/A. “Budgetary Resources Allocated for the Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity.” Inter-American Development Bank. N/A. Accessed November 10, 2019.

[10] Schneider, L. Mark. Matera, A. Michael. “Where Are the Northern Triangle Countries Headed? And What Is U.S. Policy?” Centre for Strategic and International Studies. August 20, 2019. Accessed November 11, 2019.

[11] N/A. “Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA).” Department of Homeland Security. N/A. Accessed November 12, 2019.

[12] Kight, W. Stef. Treene, Alayna. “Trump isn’t Matching Obama deportation numbers.” Axios. June 21, 2019. Accessed November 13, 2019.

[13] N/A. “Unaccompanied Alien Children: An Overview.” Congressional Research Service. October 9, 2019. Accessed November 10, 2019.

[14] N/A. “Unaccompanied Alien Children: An Overview.” Congressional Research Service. October 9, 2019. Accessed November 10, 2019.

[15] Nagovitch, Paola. “Explainer: U.S. Immigration Deals with Northern Triangle Countries and Mexico.” American Society/Council of Americans. October 3, 2019. Accessed November 10, 2019.

[16] Berg, C. Ryan. “A Central American Martial Plan Won’t Work.” Foreign Policy. March 5, 2019. Accessed November 11, 2019.

[17] Nagovitch, Paola. “Explainer: U.S. Immigration Deals with Northern Triangle Countries and Mexico.” American Society/Council of Americans. October 3, 2019. Accessed November 10, 2019.

[18] Press Release. “El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Mexico Reaffirm their Commitment to the Comprehensive Development Plan.” ECLAC. September 19,2019. Accessed November 11, 2019.

Washington alerts on the increase of violent, transnational gangs and estimates that MS-13 has reached an all-time high with 10.000 members

The Trump Administration has reported on the increase of violent, transnational gangs within the United States, specifically on Mara Salvatrucha, also known as MS-13, which also keeps a connection to the organization in Central America’s Northern Triangle. Even though United States’ President Donald Trump has addressed this issue demagogically, criminalizing immigration and overlooking the fact that said organization originated in Los Angeles, California, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) asserts such organizations are recruiting more youths than ever and demanding more violent behavior from its members. American authorities estimate these gangs are partially controlled from El Salvador, although this hierarchy is not as clear.

▲ Mara Salvatrucha graffiti [Wikimedia Commons]

ARTICLE / Lisa Cubías [Spanish version]

Never has probably an utterance of the word “animal” caused as much controversy in the US as President Donald Trump’s reference to MS-13 gang members on May 16th, 2018. Initially, it seemed as a reference to all undocumented immigrants, thus provoking immediate and widespread rejection; it was then clarified that the address referred to gang members illegally entering the United States to commit acts of violence. Trump placed his already declared war on gangs within the frame of his zero tolerance immigration policies and reinforcement of national bodies, such as the Immigration and Customs Enforcement, in order to reduce immigration flows from Latin America to the United States.

The description of the phenomenon of gangs conformed by Latin American youths as a migratory issue had already surfaced on President Trump’s State of the Union address on January 28th, 2018. Before the US Congress, he shared the story of two American teenagers, Kayla Cuevas and Nisa Mickens, who were brutally murdered by six MS-13 gang members on their way home. He asserted that the perpetrators took advantage of loopholes in immigration legislation and reiterated his stance that the US Congress must address and fill in such loopholes in order to prevent gang members from entering the United States through them.

Despite Trump’s demagogical simplification of the issue at hand, truth is that such organizations were born in the US. They are, as The Washington Post said, “as American-made as Google.” They originated in Los Angeles, California, first due to Mexican immigration and furthered by the arrival of immigrants and refugees from the armed conflicts taking place in Central America. El Salvador saw the rise and fall of long twelve years of civil war between the government and left-wing guerrilla groups during the 1980s. The extent and brutality of the conflict, along with the political and economic instability the country was undergoing propelled an exodus of Salvadorans towards the United States. The flow of youths from El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala propelled the rise of Mara Salvatrucha, also known as MS-13, and the 18th Street gang, both related to the already existing Mexican Mafia (The M).

When peace arrived in Central America during the 90s, various of such youths returned to their home countries, either following their families or expelled by American authorities due to their ongoing criminal activity. In this way it was that gangs began their criminal activity in the Northern Triangle, where to this date continue constituting a critical social problem.

Transnationality

According to the US Department of Justice, there are around 33.000 violent street gangs, with a total of 1,4 million members. MS-13, with around 10,000 enlisted youths, represents 1% from the total figure and in 2017 only 17 members were indicted, and still deserves the White House’s complete attention. At the margin of possible political interests on behalf of the Trump administration, truth is that US authorities have emphasized its increase and danger, besides stating certain commands are given all the way from El Salvador. Such transnationality is viewed in an alarming light.

The United States does not recognize MS-13 as a terrorist organization, as it is not included in their National Strategy for Counterterrorism, released during October 2018. It is instead catalogued as a transnational criminal organization, as mentioned by a document issued by the US Department of Justice on April 2017. According to the report, several of its leaders are imprisoned in El Salvador and are sending representatives to cross into the United States illegally to unify the gangs operating on US territory, while forcing US based MS-13 gangs to send their illegal profits back to gang leaders in El Salvador and motivating them to exert more control and violence over their territories.

According to the FBI, MS-13 and 18th Street “continue to expand their influence in the US.” These transnational gangs “are present in almost every state and continue to grow their memberships, now targeting younger recruits more than ever before.” The US Attorney General warned in 2017 that they numbers are “up significantly from just a few years ago.” “Transnational criminal organizations like MS-13 represent one of the gravest threats to American safety,” he said.

Stephen Richardson, assistant director of the FBI's criminal investigative division, told Congress in January 2018 that the mass arrests and imprisonment of MS-13 members and mid-level leaders over the past year in the US have frustrated MS-13 leaders in El Salvador. “They're very much interested in sending younger, more violent offenders up through their channels into this country in order to be enforcers for the gang,” he told the House Committee on Homeland Security.

The transnational character of MS-13 is contested by expert Roberto Valencia, author of articles and books on the maras. He works as journalist in El Faro, a leading investigative reporting digital media outlet in El Salvador; his latest book, titled Carta desde Zacatraz (Letter from Zacatraz), was just published some months ago.

“At first, gangs in Los Angeles served as moral guides over those who migrated back to El Salvador during the 90s. Some of the veteran leaders living now in El Salvador grew up in Los Angeles and they have kept personal and emotional ties with the gang structures where they were enrolled,” Valencia tells Global Affairs. “Notwithstanding,” he says, “that doesn’t imply an international connection: everyone, regardless of where they live, believe they are the gang’s essence and are not subordinated to other's country organization.” “They share a deeply personal relationship and that is not as easily dissolved, but the link as organization broke time ago,” he sums up.

Valencia strongly rejects any interference by the MS-13 chapter in the United States into the one in El Salvador. Instead, he admits there could be some type of influence going the other way around, as Salvadoran gang members in the United States “can be deported to El Salvador and end up in Salvadoran jails, where they can be punished by the jail mafias.”

Migrants: cause or consequence?

Roberto Valencia also addresses President Trump and his references to gangs: “Trump speaks about MS-13 in order to win votes under the premise of migration policy that ends up criminalizing every single immigrant. It is outrageous Trump presents them as the cause, when gangs actually started in the US. In fact, the vast majority of the Northern Triangle’s emigrants arrive in the United States escaping from gangs.”

In Central America, the control gangs exert over low-income territory ranges from the request of “rent” for businesses located within their areas, to forcing and threatening old women to take care of unregistered newly born children and “requesting” young girls to act as the gang’s head girlfriend or otherwise be killed along with her family. The request for young girls is an extremely common cause for migration, which also denotes the misogynistic culture in Latin American countries’ rural areas.

The majority of President Trump’s remarks have depicted MS-13 as a threat to public safety and stability of American communities. Nevertheless, the Center for Immigration Studies, prominent independent and non-profit research organization, conducted a research on MS-13 impact in the United States and the immigration measures the administration should take to control their presence. It catalogues MS-13 and other gangs as a threat to public safety, sharing President Trump’s point of view. Notwithstanding, its view is not influenced by the political landscape, and it specifically refers to gangs alone; no mention of regular immigrants or those travelling the recent caravans is made and tied with criminal activity of said impact.

Greg Hunter, American criminal defense attorney and former member from the Arlington County Bar Association Board of Directors from 2002 until 2006 and active member at the Criminal Justice Act Panel for the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia since 2001 until the present day, has closely worked with gang-related criminal cases and affirms how cases related to shoplifting and illegal migration are far more frequent than those that are catalogued as threats to public safety or to the “American community,” such as drug trafficking and murders. He also alluded to the fact that this organizations are not centralized and operate under the same identity and yet don’t follow the same orders. Efforts have been made to centralize operations but have proven ineffective.

It is crucial to consider statistical trends on the influx of immigrants in the face of the recent immigrant caravans parting from the Northern Triangle, which have proven to be a focal and recent point of discussion in the gang debate. Upon the news of their departure towards the United States, President Trump catalogued the entirety of the immigrants composing caravans as “stone cold criminals,” essentially contradicting previous US Customs and Border Protection records. In its Security Report for 2017, it depicts a total of 526,901 illegal immigrants with denied entry, from which 310,531 where apprehended and 31,039 arrested. Among the arrested immigrants there were only 228 MS-13 members (there were 61 members of the 18th Street gang as well). Instead, caravans are composed from various citizens fleeing the violence caused by MS-13 in the Northern Triangle, rather than gang members seeking to take their criminal activities towards the United States.