Breadcrumb

Blogs

Entries with Categorías Global Affairs Arabia Saudita y el Golfo Pérsico .

Con su proyecto de megaciudad y zona tecnológica los saudís buscan consolidar una vía económica alternativa al petróleo

NEOM, acrónimo de Nuevo Futuro, es el nombre de la nueva ciudad y área económico-tecnológica, con una superficie tres veces la de Chipre, que Arabia Saudí está promoviendo en el noroeste el país, frente a la Península del Sinaí. Además de buscar alternativas al petróleo, con NEOM los saudís pretenden rivalizar las innovaciones urbanísticas de Dubái, Abu Dhabi y Doha. El proyecto también supone trasladar el interés saudí del Golfo Pérsico al Mar Rojo y estrechar la vecindad con Egipto, Jordania e Israel.

![Aspecto de la futura megaciudad de NEOM, de acuerdo con la visión de sus promotores [NEOM Project] Aspecto de la futura megaciudad de NEOM, de acuerdo con la visión de sus promotores [NEOM Project]](/documents/10174/16849987/neom-blog.jpg)

▲ Aspecto de la futura megaciudad de NEOM, de acuerdo con la visión de sus promotores [NEOM Project]

ARTÍCULO / Sebastián Bruzzone Martínez

Los Estados de Oriente Medio están tratando de diversificar sus ingresos y evitar posibles colapsos de sus economías, en aras de contrarrestar la crisis del fin del petróleo previsto para mediados del siglo XXI. Los sectores preferidos por los árabes son las energías renovables, el turismo de lujo, las infraestructuras modernas y la tecnología. Los gobiernos de la región han encontrado la manera de unificar estos cuatro sectores, y Arabia Saudí, junto a los Emiratos Árabes Unidos, parece querer colocarse como el primero de la carrera tecnológica árabe.

Mientras el mundo mira hacia Sillicon Valley en California, Shenzhen en China o Bangalore en India, el gobierno saudí ha comenzado a preparar la creación de su primera zona económica y tecnológica independiente: NEOM (abreviatura del término árabe Neo-Mustaqbal, Nuevo Futuro). Al frente del proyecto estuvo hasta hace poco Klaus Kleinfeld, ex presidente de Siemens AG, quien al ser nombrado consejero de la Corona saudí ha sido sustituido por Nadhmi Al Nasr como CEO de NEOM.

El pasado 24 de octubre de 2017, en la conferencia de la Iniciativa Inversión Futura celebrada en Riad, el príncipe heredero saudita Mohammed bin Salman hizo público este proyecto de 500.000 millones de dólares, enmarcado en el programa político Saudi Vision 2030. El territorio en el que se situará NEOM está en la zona fronteriza entre Arabia Saudí, Egipto y Jordania, a orillas del Mar Rojo, por donde fluye casi un diez por ciento del comercio mundial, existe una temperatura 10º C inferior a la media del resto de países del Consejo de Cooperación del Golfo, y se localiza a menos de ocho horas de vuelo del 70% de la población del planeta, por lo que podría convertirse en un gran centro de transporte de pasajeros.

Según ha anunciado el gobierno saudí, NEOM será una ciudad económica especial, con sus propias leyes civiles y tributarias, y costumbres sociales occidentales, de 26.500 kilómetros cuadrados (el tamaño de Chipre multiplicado por tres). Los objetivos principales son atraer la inversión extranjera de empresas multinacionales, diversificar la economía saudita dependiente del petróleo, crear un espacio de libre mercado y hogar de millonarios, “una tierra para gente libre y sin estrés; una start-up del tamaño de un país: una hoja en blanco en la que escribir la nueva era del progreso humano", dice un vídeo promocional del proyecto. Todo ello bajo el eslogan: “The world’s most ambitious project: an entire new land, purpose-built for a new way of living”. Según la página web y cuentas oficiales del proyecto, los 16 sectores de energía, movilidad, agua, biotecnología, comida, manufactura, comunicación, entretenimiento y moda, tecnología, turismo, deporte, servicios, salud y bienestar, educación, y habitabilidad generarán 100.000 millones de dólares al año.

Gracias a un informe publicado por el diario The Wall Street Journal y elaborado por las consultoras Oliver Wyman, Boston Consulting Group y McKinsey & Co., que, según aseguran, tuvieron acceso a más de 2.300 documentos confidenciales de planificación, han salido a la luz algunas de las ambiciones y lujos con los que contará la urbe futurista. Entre ellos se encuentran coches voladores, hologramas, un parque temático de dinosaurios robot y edición genética al estilo Jurassic Park, tecnologías e infraestructuras nunca vistas, hoteles, resorts y restaurantes de lujo, mecanismos que creen nubes para causar precipitaciones en zonas áridas, playas con arena que brilla en la oscuridad, e incluso una luna artificial.

Otro fin que busca el proyecto es hacer de NEOM la ciudad más segura del planeta, mediante sistemas de vigilancia de última generación que incluyen drones, cámaras automatizadas, máquinas de reconocimiento facial y biométrico y una IA capaz de notificar delitos sin necesidad de que los ciudadanos tengan que denunciarlos. Del mismo modo, los propios dirigentes de la iniciativa urbanística auguran que la ciudad será un centro ecológico de gran proyección, basando su sistema de alimentación únicamente en energía solar y eólica obtenida con placas y molinos, pues tienen todo un desierto para instalarlos.

Por el momento, NEOM no es más que un proyecto que está en fase de iniciación. El territorio en el que se situará la gran ciudad es un terreno de desierto, montañas de hasta 2.500 metros de altura y 468 kilómetros de costas vírgenes de agua azul turquesa, con un palacio y un pequeño aeropuerto. NEOM está siendo construida desde la nada, con un desembolso inicial de 9.000 millones de dólares del fondo soberano saudita Saudi Arabia Monetary Authority (SAMA). Aparte de inversión empresarial extranjera, el gobierno saudí está buscando trabajadores de todos los sectores profesionales para que ayuden en sus respectivos campos: juristas que elaboren un código civil, penal y tributario; ingenieros y arquitectos que diseñen un plan de infraestructuras y energías moderno, eficiente y tecnológico; diplomáticos que colaboren en su promoción y convivencia cultural; científicos y médicos que incentiven la investigación clínica y biotecnológica y el bienestar; académicos que potencien la educación; economistas que rentabilicen los ingresos y gastos; personalidades especializadas en turismo, moda y telecomunicaciones… Pero, sobre todo, personas y familias que habiten y den vida a la ciudad.

Según ha informado el periódico árabe Rai Al Youm, Mohammed bin Salman ha aprobado una propuesta elaborada por un comité legal saudí conjunto con Reino Unido que consiste en aportar un documento VIP que ofrecerá visas especiales, derechos de residencia a inversores, altos funcionarios y trabajadores de la futura ciudad. Ya se han adjudicado contratos a la empresa de ingeniería estadounidense Aecom y de construcción a la inglesa Arup Group, a la canadiense WSP, y a la holandesa Fugro NV.

Sin embargo, no todo es tan ideal y sencillo como parece. A pesar del gran interés de 400 empresas extranjeras en el proyecto, según asegura el gobierno local, existe incertidumbre sobre su rentabilidad. Los problemas y escándalos relacionados con la corona saudí, como el encarcelamiento de familiares y disidentes, la corrupción, la desigualdad de derechos, la intervención militar en Yemen, el caso del asesinato del periodista Khashoggi y la posible crisis política tras la futura muerte del rey Salman bin Abdulaziz, padre de Mohammed, han hecho que los inversores anden con pies de plomo. Además, en la región sobre la que se pretende construir la ciudad existen pueblos de lugareños que serían reubicados, y “compensados y apoyados por programas sociales”, según asegura el gobierno saudí, lo que será objeto de reproche por grupos de defensores de derechos humanos.

En conclusión, NEOM es un proyecto único y a la altura de los propios jeques árabes, los cuales han adoptado una visión económica previsora. Se espera que en 2030 ya sea posible vivir en la ciudad, a pesar de que las construcciones sigan su curso y no estén completamente finalizadas. Según los mercados, el proyecto, aún lejos de su culminación, parece estar encauzado. Ya cuenta con un compromiso de financiación de estructura con BlackStone de 20.000 millones de euros, y de tecnología con SoftBank de 45.000 millones de euros. Debido a que nunca se ha visto un proyecto así y por tanto no existen referencias, es difícil determinar si el visionario plan se consolidará con éxito o se quedará en simple humo y pérdidas enormes de dinero.

![Vista de Doha, la capital de Catar, desde su Museo Islámico [Pixabay] Vista de Doha, la capital de Catar, desde su Museo Islámico [Pixabay]](/documents/10174/16849987/qatar-blog.jpg)

▲ Vista de Doha, la capital de Catar, desde su Museo Islámico [Pixabay]

ENSAYO / Sebastián Bruzzone Martínez

I. Introducción. Catar, emirato del golfo pérsico

En la antigüedad, el territorio era habitado por los cananeos. A partir del siglo VII d.C., el Islam se asentó en la península de Qatar. Como en los Emiratos Árabes Unidos, la piratería y los ataques a los barcos mercantes de potencias que navegaban por las costas del Golfo Pérsico eran frecuentes. Catar estuvo gobernado por la familia Al Khalifa, procedentes de Kuwait, hasta 1868, cuando a petición de los jeques cataríes y con ayuda de los británicos se instauró la dinastía Al Thani. En 1871, el Imperio Otomano ocupó el país, y la dinastía catarí reconoció la autoridad turca. En 1913, Catar consiguió la autonomía; tres años más tarde, el emir Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani firmó un tratado con Reino Unido para implantar un protectorado militar británico en la región, pero manteniendo la monarquía absoluta del emir.

En 1968, Reino Unido retiró su fuerza militar, y los Estados de la Tregua (Emiratos Árabes Unidos, Catar y Bahréin) organizaron la Federación de Emiratos del Golfo Pérsico. Catar, al igual que Bahréin, se independizó de la Federación en 1971, proclamó una Constitución provisional, firmó un tratado de amistad con Reino Unido e ingresó en la Liga Árabe y en la ONU.

La Constitución provisional fue sustituida por la Constitución de 2003 de 150 artículos, sometida a referéndum y apoyada por el 98% de los electores. Entró en vigor como norma fundamental el 9 de abril de 2004. En ella se reconoce el Islam como religión oficial del Estado y la ley Sharia como fuente de Derecho (art. 1); la previsión de adhesión y respeto a los tratados, pactos y acuerdos internacionales firmados por el Emirato de Catar (art. 6); el gobierno hereditario de la familia Al Thani (art. 8); instituciones ejecutivas como el Consejo de Ministros y legislativo-consultivas como el Consejo Al Shoura o Consejo de la Familia Gobernante. Asimismo figuran la posibilidad de la regencia mediante el Concejo fiduciario (arts. 13-16), la institución del primer ministro designado por el emir (art. 72), el emir como jefe de Estado y representante del Estado en Interior, Exterior y Relaciones Internacionales (arts. 64-66), un fondo soberano (Qatar Investment Company; art. 17), instituciones judiciales como los Tribunales locales y el Consejo Judicial Supremo, y su control sobre la inconstitucionalidad de las leyes (137-140)[1], entre otros aspectos.

También se reconocen derechos como la propiedad privada (art. 27), igualdad de derechos y deberes (art. 34), igualdad de las personas ante la ley sin ser discriminadas por razón de sexo, raza, idioma o religión (art. 35), libertad de expresión (art. 47), libertad de prensa (art. 48), imparcialidad de la justicia y tutela judicial efectiva (134-136), entre otros.

Estos derechos reconocidos en la Constitución catarí deben ser consecuentes con la ley islámica, siendo así su aplicación diferente a la que se observa en Europa o Estados Unidos. Por ejemplo, a pesar de que en su artículo 1 está reconocida la democracia como sistema político del Estado, los partidos políticos no existen; y los sindicatos están prohibidos, aunque el derecho de asociación está reconocido por la Constitución. Del mismo modo, el 80% de la población del país es extranjera, siendo estos derechos constitucionales aplicables a los ciudadanos cataríes, que conforman el 20% restante.

Como el resto de los países de la zona, el petróleo ha sido factor transformador de la economía catarí. Hoy en día, Catar tiene un alto nivel de vida y uno de los PIB per cápita más altos del mundo[2], y constituye un destino atractivo para los inversores extranjeros y el turismo de lujo. Sin embargo, en los últimos años Catar está viviendo una crisis diplomática[3] con sus países vecinos del Golfo Pérsico debido a distintos factores que han condenado al país árabe al aislamiento regional.

II. La inestabilidad de la familia al thani

El gobierno del Emirato de Catar ha sufrido una gran inestabilidad a causa de las disputas internas de la familia Al Thani. Peter Salisbury, experto en Oriente Medio de Chatham House, el Real Instituto de Asuntos Internacionales de Londres, habló de los Al Thani en una entrevista para la BBC: “Es una familia que en un inicio (antes del descubrimiento del petróleo) gobernaba un pedazo de tierra, pequeño e insignificante, que a menudo era visto como una pequeña provincia de Arabia Saudita. Pero logró forjarse una posición en esa región de gigantes”. [4]

En 1972, mediante un golpe de Estado, Ahmed Al Thani fue depuesto por su primo Khalifa Al Thani, con el que Catar siguió una política internacional de no intervención y búsqueda de paz interna, y mantuvo una buena relación con Arabia Saudita. Se mantuvo en el poder hasta 1995, cuando su hijo Hamad Al Thani le destronó aprovechando una ausencia del mandatario, de viaje en Suiza. El gobierno saudí vio la actuación como un mal ejemplo para los demás países de la región también gobernados por dinastías familiares. Hamad potenció la exportación de gas natural licuado y petróleo, y desmanteló un supuesto plan de los saudíes de restituir a su padre Khalifa. Los países de la región comenzaron a ver cómo el “pequeño de los hermanos” crecía económica e internacionalmente muy rápido con el nuevo emir y su ministro de Exteriores Hamam Al Thani.

La familia está estructurada en torno a Hamad y su esposa Mozah bint Nasser Al-Missned, quien se ha convertido en un icono de la moda y prestigio femenino de la nobleza internacional, al nivel de Rania de Jordania, Kate Middleton o la reina Letizia (precisamente el matrimonio es cercano a la familia real española).

Hamad abdicó en su hijo Tamim Al Thani en 2013. El ascenso de este fue un soplo de esperanza de corta duración para la comunidad árabe internacional. Tamim adoptó una posición de política internacional muy similar a la de su padre, fortaleciendo el acercamiento y cooperación económica con Irán, y aumentando la tensión con Arabia Saudita, que procedió a cerrar la única frontera terrestre que tiene Catar. Del mismo modo, según una filtración de WikiLeaks en 2009, el jeque Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan acusó a Tamim de pertenecer a los Hermanos Musulmanes. Por otro lado, la rivalidad económica, política, social e incluso personal entre los Al Thani de Catar y los Al Saud de Arabia Saudita se remonta a décadas atrás.

Desde mi punto de vista, la estabilidad y jerarquía familiar en las naciones gobernadas por dinastías es un factor crucial para evitar luchas de poder internas que por consecuencia tienen grandes efectos negativos para la sociedad del país. Cada persona posee ideas políticas, económicas y sociales diferentes que llevan tiempo aplicarlas. Los cambios frecuentes y sin una culminación objetiva terminan siendo un factor terriblemente desestabilizador. En el ámbito internacional, la credibilidad y rigidez política del país puede verse mermada cuando el hijo del emir da un golpe de Estado cuando su padre está de vacaciones. Catar, consciente de ello, en el artículo 148 de su Constitución buscó la seguridad y rigidez legislativa prohibiendo la enmienda de ningún artículo antes de haberse cumplido diez años de su entrada en vigor.

En 1976, Catar reivindicó la soberanía de las islas Hawar, controladas por la familia real de Bahréin, que se convirtieron en un foco de conflicto entre ambas naciones. Sucedió lo mismo con la isla artificial de Fasht Ad Dibal, lo que llevó al ejército de Catar a realizar una incursión en la isla en 1986. Fue abandonada por Catar en un acuerdo de paz con Bahréin.

III. Supuesto apoyo a grupos terroristas

Es la causa principal por la que los Estados vecinos han aislado a Catar. Egipto, Emiratos Árabes Unidos, Arabia Saudita, Bahréin, Libia y Maldivas, entre otros, cortaron relaciones diplomáticas y comerciales con Catar en junio de 2017 por su supuesta financiación y apoyo a los Hermanos Musulmanes, a quienes consideran una organización terrorista. En 2010, WikiLeaks filtró una nota diplomática en la que Estados Unidos calificaba a Catar como el “peor de la región en materia de cooperación para eliminar la financiación de grupos terroristas.”

La hermandad musulmana, cuyo origen se encuentra en 1928 con Hassan Al Bana, en Egipto, es un movimiento político activista e islámico, con principios basados en el nacionalismo, la justicia social y el anticolonialismo. De todos modos, dentro del movimiento existen varias corrientes, algunas más rigurosas que otras. Los fundadores de los Hermanos Musulmanes ven la educación de la sociedad como la herramienta más efectiva para llegar al poder de los Estados. Por ello, los adoctrinadores o evangelizadores del movimiento son los más perseguidos por las autoridades de los países que condenan la pertenencia al grupo. Está dotada de una estructura interna bien definida, cuya cabeza es el guía supremo Murchid, asistido por un órgano ejecutivo, un consejo y una asamblea.

A partir de 1940, se inicia la actividad paramilitar del grupo de forma clandestina con Nizzam Al Khas, cuya intención inicial era lograr la independencia de Egipto y expulsar a los sionistas de Palestina. Realizaron atentados como el asesinato del primer ministro egipcio Mahmoud An Nukrashi. La creación de esta sección especial sentenció de manera definitiva la reputación y el carácter violento de los Hermanos Musulmanes, que continuaron su expansión por el mundo bajo la forma de Tanzim Al Dawli, su estructura internacional.[5]

En la capital de Catar, Doha, se encuentra exiliado Khaled Mashal,[6] ex líder de la organización militante Hamas, y los talibanes de Afganistán poseen una oficina política. Es importante saber que la mayoría de los ciudadanos cataríes son seguidores del wahabismo, una versión puritana del Islam que busca la interpretación literal del Corán y Sunnah, fundada por Mohammad ibn Abd Al Wahhab.

Durante la crisis política posterior a la Primavera Árabe en 2011, Catar apoyó los esfuerzos electorales de los Hermanos Musulmanes en los países del norte de África. El movimiento islamista vio la revolución como un medio útil para acceder a los gobiernos, aprovechando el vacío de poder. En Egipto, Mohamed Mursi, ligado al movimiento, se convirtió en presidente en 2013, aunque fue derrocado por los militares. Emiratos Árabes Unidos y Bahréin calificaron negativamente el apoyo y lo vieron como un elemento islamista desestabilizador. En aquellos países en los que no tuvieron éxito, sus miembros fueron expulsados y muchos se refugiaron en Catar. Mientras tanto, en los países vecinos de la región saltaban las alarmas y seguían atentamente cada movimiento pro-islamista del gobierno catarí.

Del mismo modo, fuentes holandesas y la abogada de Derechos Humanos Liesbeth Zegveld acusaron a Catar de financiar el Frente Al Nusra[7], la rama siria de Al Qaeda que participa en la guerra contra Al Assad, declarada organización terrorista por Estados Unidos y la ONU. La abogada holandesa afirmó en 2018 poseer las pruebas necesarias para demostrar el flujo de dinero catarí hacia Al Nusra a través de empresas basadas en el país y responsabilizar judicialmente a Catar ante el tribunal de La Haya, por las víctimas de la guerra en Siria. Es importante saber que, en 2015, Doha consiguió la liberación 15 soldados libaneses, pero a cambio de la liberación de 13 terroristas detenidos. Otras fuentes aseguran el pago de veinte millones de euros por parte de Catar para la liberar a 45 cascos azules de Fiyi secuestrados por Al Nusra en los Altos del Golán.

Según la BBC, en diciembre de 2015, Kataeb Hezbolá o Movimiento de Resistencia Islámica de Irak, reconocido como organización terrorista por Emiratos Árabes Unidos y Estados Unidos, entre otros, secuestró a un grupo de cataríes que fueron de cacería a Irak.[8] Entre los cazadores del grupo se encontraban dos miembros de la familia real catarí, el primo y el tío de Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani, ministro de Relaciones Exteriores de Catar desde 2016. Tras 16 meses de negociaciones, los secuestradores exigieron al embajador catarí en Irak la escalofriante cifra de mil millones de dólares para liberar a los rehenes. Según funcionarios de Qatar Airways, en abril de 2017 un avión de la compañía voló a Bagdad con el dinero para ser entregado al gobierno iraquí, que actuaría como intermediario entre Hezbolá y Catar. Sin embargo, la empresa nunca ha comentado los hechos. La versión oficial del gobierno catarí es que nunca se pagó a los terroristas y se consiguió la liberación de los rehenes mediante una negociación diplomática conjunta entre Catar e Irak.

La financiación de Catar al grupo armado Hamás de la Franja de Gaza es un hecho real. En noviembre de 2018, según fuentes israelíes, Catar pagó quince millones de dólares en efectivo como parte de un acuerdo con Israel negociado por Egipto y la ONU, que abarcaría un total de noventa millones de dólares fraccionado en varios pagos[9], con intención de buscar la paz y reconciliación entre los partidos políticos Fatah y Hamas, considerado grupo terrorista por Estados Unidos.

IV. La relación catarí con Irán

Catar posee buenas relaciones diplomáticas y comerciales con Irán, mayoritariamente chiita, lo cual no es del agrado del Cuarteto (Egipto, Arabia Saudita, EAU, y Bahréin), mayoritariamente sunita, en especial de Arabia Saudita, con quien mantiene una evidente confrontación –subsidiaria, no directa– por la influencia política y económica predominante en la región pérsica. En 2017, en su última visita a Riad, Donald Trump pidió a los países de la región que aislasen a Irán por la tensión militar y nuclear que vive con Estados Unidos. Catar actúa como intermediario y punto de inflexión entre EEUU e Irán, tratando de abrir la vía del diálogo en relación con las sanciones implantadas por el presidente americano.

Doha y Teherán mantienen una fuerte relación económica en torno a la industria petrolífera y gasística, ya que comparten el yacimiento de gas más grande del mundo, el South Pars-North Dame, mientras que Arabia Saudita y Emiratos Árabes Unidos han seguido la corriente estadounidense en sus programas de política exterior en relación con Irán. Una de las condiciones que el Cuarteto exige a Catar para levantar el bloqueo económico y diplomático es el cese de las relaciones bilaterales con Irán, reinstauradas en 2016, y el establecimiento de una conducta comercial con Irán en conformidad con las sanciones impuestas por Estados Unidos.

V. Cadena de televisión Al Jazeera

Fundada en 1996 por Hamad Al Thani, la cadena Al Jazeera se ha convertido en el medio digital más influyente de Oriente Medio. Se colocó como promotora de la Primavera Árabe y estuvo presente en los climas de violencia de los distintos países. Por ello, ha sido criticada por los antagonistas de Catar por sus posiciones cercanas a los movimientos islamistas, por ejercer de portavoz para los mensajes fundamentalistas de los Hermanos Musulmanes y por constituirse en vehículo de la diplomacia catarí. Su clausura ha sido uno de los requisitos que el Cuarteto ha solicitado a Catar para levantar el bloqueo económico, el tránsito de personas y la apertura del espacio aéreo.

Estados Unidos acusa a la cadena de ser el portavoz de grupos islámicos extremistas desde que el anterior jefe de Al Qaeda, Osama bin Laden, comenzara a divulgar sus comunicados a través de ella; de poseer carácter antisemita, y de adoptar una posición favorable al grupo armado Hamas en el conflicto palestino-israelí.

En 2003, Arabia Saudita, tras varios intentos fallidos de provocar el cierre de la cadena de televisión catarí, decidió crear una televisión competidora, Al Arabiya TV, iniciando una guerra de desinformación y rivalizando sobre cuál de las dos posee la información más fiable.

VI. La posición de Washington y Londres

Por un lado, Estados Unidos busca tener una relación buena con Catar, pues allí tiene la gran base militar de Al-Udeid, que cuenta con una excelente posición estratégica en el Golfo Pérsico y más de diez mil efectivos. En abril de 2018, el emir catarí visitó a Donald Trump en la Casa Blanca, quien dijo que la relación entre ambos países “funciona extremadamente bien” y considera a Tamim un “gran amigo” y “un gran caballero”. Tamim Al Thani ha resaltado que Catar no tolerará a personas que financian el terrorismo y ha confirmado que Doha cooperará con Washington para poner fin a la financiación de grupos terroristas.

La contradicción es clara: Catar confirma su compromiso en la lucha contra la financiación de grupos terroristas, pero su historial no le avala. Hasta ahora, ha quedado demostrado que el pequeño país ha ayudado a estos grupos de una manera u otra, mediante asilo político y protección de sus miembros, financiación directa o indirecta a través de controvertidas técnicas de negociación, o promoviendo intereses políticos que no han sido del agrado de su gran rival geopolítico, Arabia Saudita.

Estados Unidos es el gran mediador e impedimento del enfrentamiento directo en la tensión entre Arabia Saudita y Catar. Ambos países son miembros de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas y aliados de EEUU. Europa y los presidentes americanos han sido conscientes de que un enfrentamiento directo entre ambos países puede resultar fatal para la región y sus intereses comerciales relacionados con el petróleo y el estrecho de Ormuz.

Por otro lado, el gobierno de Reino Unido se ha mantenido distante a la hora de adoptar una posición en la crisis diplomática de Catar. El emir Tamim Al Thani es dueño del 95% del edificio The Shard, el 8% de la bolsa de valores de Londres y del banco Barclays, así como de apartamentos, acciones y participaciones de empresas en la capital inglesa. Las inversiones cataríes en la capital de Reino Unido rondan un total de sesenta mil millones de dólares.

En 2016, el ex primer ministro británico David Cameron mostró su preocupación sobre el futuro cuando la alcaldía de Londres fue ocupada por Sadiq Khan, musulmán, que ha aparecido en más de una ocasión junto a Sulaiman Gani, un imán que apoya al Estado Islámico y a los Hermanos Musulmanes.[10]

VII. Guerra civil en Yemen

Desde que se inició la intervención militar extranjera en la guerra civil de Yemen en 2015, a petición del presidente yemení Rabbu Mansur Al Hadi, Catar se alineó junto a los Estados del Consejo de Cooperación para los Estados Árabes del Golfo (Bahréin, Kuwait, Omán, Catar, Arabia Saudita y los Emiratos Árabes Unidos), respaldados por Estados Unidos, Reino Unido y Francia, para crear una coalición internacional que ayudara a restituir el poder legítimo de Al Hadi, puesto en jaque desde el golpe de Estado promovido por hutíes y fuerzas leales al ex presidente Ali Abdala Saleh. Sin embargo, Catar ha sido acusado de apoyar de forma clandestina a los rebeldes hutíes[11], por lo que el resto de los países del Consejo miran sus actuaciones con gran cautela.

Actualmente, la guerra civil yemení se ha convertido en la mayor crisis humanitaria desde 1945.[12] El 11 de agosto de 2019, los separatistas del Sur de Yemen, respaldados por Emiratos Árabes Unidos, que en un principio apoya el gobierno de Al Hadi, tomaron la ciudad portuaria de Adén, asaltando el palacio presidencial y las bases militares. El presidente, exiliado en Riad, ha calificado el ataque de sus aliados como un golpe a las instituciones del Estado legítimo, y ha recibido el apoyo directo de Arabia Saudita. Tras unos días de tensión, los separatistas del Movimiento del Sur abandonaron la ciudad.

Emiratos y Arabia Saudita, junto a otros Estados vecinos como Bahréin o Kuwait, de creencia sunita, buscan frenar el avance de los hutíes, que dominan la capital, Saná, y una posible expansión del chiísmo promovido por Irán a través del conflicto de Yemen. Del mismo modo, influye el gran interés geopolítico del Estrecho de Bab el Mandeb, que conecta el Mar Rojo con el Mar Arábigo y resulta una gran alternativa al flujo comercial del Estrecho de Ormuz, frente a las costas de Irán. Dicho interés es compartido con Francia y Estados Unidos, que busca eliminar la presencia de ISIS y Al Qaeda de la región.

Al día siguiente de la toma de Adén, y en plenas celebraciones de Eid Al-Adha, el príncipe heredero de Abu Dhabi, Mohammed bin Zayed, se reunió en La Meca con el rey saudí, Salman bin Abdelaziz, y el príncipe heredero saudí, Mohammed bin Salman, en un aparente esfuerzo de reducir la importancia del suceso, hacer un llamamiento a las partes en conflicto en la ciudad para salvaguardar los intereses de Yemen, y reafirmar la cooperación regional y unidad de intereses entre EAU y Arabia Saudita.[13] El príncipe heredero de Abu Dhabi ha publicado en sus cuentas oficiales de Twitter comentarios y fotografías de la reunión en las que se puede observar una actitud positiva en los rostros de los dirigentes.

A contrario sensu, si la colaboración y entendimiento en la cuestión de Yemen entre ambos países fuesen totales, como afirmaron, no sería necesario crear una imagen aparentemente “ideal” mediante comunicaciones oficiales del gobierno de Abu Dhabi y la publicación de imágenes en redes sociales.

A pesar de que EAU apoya a los separatistas, los últimos hechos han causado una sensación de desconfianza, abriendo la posibilidad de que las milicias del Sur estén desoyendo las directrices emiratíes y comenzando a ejecutar una agenda propia afín a sus intereses particulares. Asimismo, las fuentes extranjeras comienzan a hablar de una guerra civil dentro de una guerra civil. Mientras tanto, Catar se mantiene próximo a Irán y cauto ante la situación del suroeste de la Península Arábiga.

![Visa aérea de Dubái [Pixabay] Visa aérea de Dubái [Pixabay]](/documents/10174/16849987/emiratos-blog.jpg)

▲ Visa aérea de Dubái [Pixabay]

ENSAYO / Sebastián Bruzzone Martínez

I. ORIGEN Y FUNDACIÓN DE LOS EMIRATOS ÁRABES UNIDOS

En la antigüedad, el territorio era habitado por tribus árabes, nómadas agricultores, artesanos y comerciantes, acostumbradas a saquear barcos mercantes de potencias europeas que navegaban por sus costas. El Islam se asienta en la cultura local en el siglo VII d.C., y el Islam sunní en el siglo XI d.C. A partir de 1820, Reino Unido firma con los dirigentes o jeques de la zona un tratado de paz para poner fin a la piratería. En 1853, ambas partes firmaron otro acuerdo por el que Reino Unido establecía un protectorado militar en el territorio. Y en 1892, por las pretensiones de Rusia, Francia y Alemania, firmaron un tercer acuerdo que garantizaba el monopolio sobre el comercio y explotación únicamente para los británicos. La zona emiratí pasó de llamarse “Costa de los piratas” a “Estados de la Tregua” o “Trucial States” (los actuales siete Emiratos Árabes Unidos, Catar y Bahréin).

Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, los aeródromos y puertos del Golfo tomaron un importante papel en el desarrollo del conflicto en favor de Reino Unido. Al término de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en 1945, se creó la Liga de Estados Árabes (Liga Árabe), formada por aquellos que gozaban de cierta independencia colonial. La organización llamó la atención de los Estados de la Tregua.

En 1960, se crea la Organización de Países Exportadores de Petróleo (OPEP), siendo Arabia Saudita, Irán, Irak, Kuwait y Venezuela sus fundadores y con sede en Viena, Austria. Los siete emiratos, que posteriormente formarían los Emiratos Árabes Unidos, se unieron en 1967.

En 1968, Reino Unido retira su fuerza militar de la región, y los Estados de la Tregua organizaron la Federación de Emiratos del Golfo Pérsico, pero fracasó al independizarse Catar y Bahréin. En los años posteriores, se inicia la explotación de los enormes pozos petrolíferos descubiertos años atrás.

En 1971, seis Emiratos se independizaron del imperio británico: Abu Dhabi, Dubái, Sharjah, Ajmán, Umm al Qaywayn y Fujairah, formando la federación de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos, con un sistema legal basado en la constitución de 1971. Una vez consolidada, el 12 de junio se unieron a la Liga Árabe. El séptimo emirato, Ras Al-Khaimah se adhirió al año siguiente.

A partir de la crisis del petróleo de 1973, los Emiratos comenzaron a acumular una enorme riqueza, debido a que los miembros de la OPEP decidieron no exportar más petróleo a los países que apoyaron a Israel durante la guerra de Yom Kipur. Actualmente, el 80-85% de la población de EAU es inmigrante. Emiratos Árabes Unidos pasó a ser el tercer productor de petróleo de Oriente Medio, tras Arabia Saudita y Libia.

II. SISTEMA POLÍTICO Y LEGAL

Por la constitución de 1971, los Emiratos Árabes Unidos se constituyen en una monarquía federal. Cada Estado es regido por su emir (título nobiliario de los jeques, Sheikh). Cada emirato, posee una gran autonomía política, legislativa, económica y judicial, teniendo cada uno sus consejos ejecutivos, siempre en correspondencia con el gobierno federal. No existen los partidos políticos. Las autoridades federales se componen de:

Consejo Supremo de la Federación o de Emires: es la suprema autoridad del Estado. Está compuesta por los gobernadores de los 7 Emiratos, o quienes los sustituyen en su ausencia. Cada Emirato tiene un voto en las deliberaciones. Establece la política general en las cuestiones confiadas a la Federación, y estudia y establece los objetivos e intereses de la misma.

Presidente y Vicepresidente de la Federación: elegidos por el Consejo Supremo entre sus miembros. El Presidente ejerce, en virtud de la Constitución, competencias importantes como la presidencia del Consejo Supremo; firma de leyes, decretos o resoluciones que ratifica y dicta el Consejo; nombramiento del Presidente del Consejo de Ministros y del Vicepresidente y ministros; aceptación de sus dimisiones o su suspensión de funciones a propuesta del Presidente del Consejo de Ministros. El Vicepresidente ejerce todas las atribuciones presidenciales en su ausencia.

Por tradición, no reconocida en la Constitución emiratí, el jeque de Abu Dhabi es el presidente del país, y el jeque de Dubái es el vicepresidente y Primer Ministro.

Así, actualmente, Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, jeque de Abu Dhabi, es el presidente de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos desde 2004; y Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, jeque de Dubái, es el Primer Ministro y vicepresidente desde 2006.

Consejo de ministros: compuesto por el Presidente del Consejo de Ministros, el Vicepresidente y los ministros. Es el órgano ejecutivo de la Federación. Supervisado por el Presidente y Consejo Supremo, su misión es gestionar los asuntos de interior y exterior, que sean de competencia de la Federación en virtud de la Constitución y leyes federales. Posee ciertas prerrogativas como hacer un seguimiento de la aplicación de la política general del Estado Federal en el interior y exterior; proponer proyectos de leyes federales y trasladarlos al Consejo Supremo de la Federación; supervisar la ejecución de las leyes y resoluciones federales, y la aplicación de tratados y convenios internacionales firmados por los Emiratos Árabes Unidos.

Asamblea Federal Nacional: lo que se asemejaría a un Congreso, pero es un órgano únicamente consultivo. Está compuesto por 40 miembros: veinte elegidos por los ciudadanos con derecho a voto, por sufragio censitario, de Emiratos Árabes Unidos a través de elección general, y la otra mitad por los gobernantes de cada Emirato. En diciembre de 2018, el presidente, Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, emitió un decreto que contempla que el cincuenta por ciento de la Asamblea Federal Nacional (o FNC, por sus siglas en inglés) sea ocupado por mujeres, con intención de “empoderar aún más a las mujeres emiratíes y reforzar sus contribuciones al desarrollo del país”. Está distribuido con escaños: Abu Dhabi (8); Dubái (8); Sharjah (6); Ras Al Khaimah (6); Ajmán (4); Umm Al Quwayn (4); y Fujairah (4). A él se elevan los proyectos de ley federales y financieros antes de ser presentados al Presidente de la Federación a fin de que los someta al Consejo Supremo para su ratificación. También, le compete al Gobierno notificar a la Asamblea los pactos y tratados internacionales. La Asamblea estudia y realiza recomendaciones respecto a temas de carácter público.

La Administración de Justicia Federal: el sistema judicial de Emiratos Árabes Unidos está basado en la ley Sharia o ley islámica. El artículo 94 de la Constitución establece que la justicia es la base del Gobierno y reafirma la independencia del poder judicial, estipulando que no existe autoridad ninguna por encima de los jueces, salvo la ley y su propia conciencia en el ejercicio de sus funciones. El sistema de justicia federal se compone de tribunales de primera instancia y tribunales y de apelación (de lo civil, penal, comercial, contencioso-administrativo…)

También, existe un Tribunal Supremo Federal, constituido por un presidente y jueces vocales, con competencias como estudiar la constitucionalidad de las leyes federales y los actos inconstitucionales.

Además, La Administración de Justicia local entenderá de todos aquellos casos judiciales que no competan a la Administración federal. Cuenta con tres niveles: primera instancia, de apelación y casación.

La Constitución prevé la existencia de un Fiscal General, que preside la Fiscalía Pública Federal, encargada de presentar pliegos de cargo en delitos cometidos con arreglo a las disposiciones del Código y Procedimiento penal de la Federación.

Para promover el entendimiento entre administraciones federal y local, desde 2007 se ha constituido un Consejo de Coordinación Judicial, presidido por el Ministro de Justicia y compuesto por presidentes y directores de los órganos judiciales del Estado. [1]

Es importante saber que la Constitución de la Federación posee garantías de refuerzo y protección de los derechos humanos en su capítulo III de las libertades, los derechos y obligaciones públicas, como el principio de igualdad en razón de extracción, lugar de nacimiento, creencia religiosa o posición social, aunque no menciona género, y justicia social (art. 25); la libertad de los ciudadanos (art. 26); la libertad de opinión y garantía de los medios para expresarla (art. 30); libertad de circulación y de residencia (art. 29); libertad religiosa (art.32); derecho a la privacidad (art. 31 y 36); derechos de la familia (art. 15); derecho a previsión social y a la seguridad social (art. 16); derecho a la educación (art. 17); derecho a la atención sanitaria (art. 19); derecho al trabajo (art. 20); derecho de asociación y de constitución de asociaciones (art. 33); derecho a la propiedad (art. 21); y derecho de queja y derecho a litigar ante los tribunales (art. 41).[2]

A simple vista, parece que estos derechos y garantías que recoge la Constitución emiratí de 1971 son semejantes a los que recogería una Constitución europea y occidental normal. Sin embargo, son matizables y no tan efectivos en la práctica. Por un lado, porque la mayoría de ellos incluyen remisiones a la ley concreta y aplicable, diciendo “…en los límites que marca la ley; en conformidad con las disposiciones que marca la ley; o en los casos en que así lo disponga la ley”. De esta forma, el legislador se encargará de que estos derechos sean consecuentes y compatibles con la Ley Sharia o islámica, o con los intereses políticos, en su caso.

Por otro lado, estos derechos y garantías protegen de manera completa a los ciudadanos emiratíes, nacionales. Teniendo en cuenta, que el 80-85% de la población es extranjera, se estaría protegiendo de forma íntegramente constitucional a un 15% de la población total del Estado. Por la Ley Federal Nº28/2005 relativa al estatuto personal, la ley se aplica a todos los ciudadanos del Estado de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos siempre que no existan, para los no musulmanes de entre ellos, disposiciones especiales específicas para su confesión o religión. Igualmente, se aplican sus disposiciones a los no nacionales cuando no estén obligados a cumplir la legislación de su propio país.

Entre salvaguardias jurídicas destacan el Código Penal Federal (Ley Nº3/1987); el Código de Procedimiento Penal (Ley Nº 35/1992); Ley Federal sobre la regulación de las instituciones de reforma penitenciaria (Nº43/1992); Ley Federal sobre regulación de las relaciones laborales (Nº8/1980); Ley Federal relativa a la lucha contra la trata de personas (Nº 51/2006); Ley Federal relativa al estatuto personal (Nº28/2005); Ley Federal relativa a los menores delincuentes y carentes de hogar (Nº9/1976); Ley Federal sobre publicaciones y edición (Nº15/1980); Ley Federal sobre regulación de órganos humanos (Nº15/1993); Ley Federal relativa a las asociaciones declaradas de interés público (Nº2/2008); Ley Federal sobre previsión social (Nº2/2001); Ley Federal sobre pensiones y seguros sociales (Nº7/1999); Ley Federal de protección y desarrollo del medio ambiente (Nº24/1999); y Ley Federal relativa a los derechos de las personas con necesidades especiales (Nº29/2006).

El servicio militar de 9 meses es obligatorio para los hombres universitarios entre 18 y 30 años, y de dos años para los que no tienen estudios superiores. Para las mujeres es opcional y sometido al acuerdo de su tutor. Aunque el país no es miembro de la OTAN, los Emiratos han decidido unirse a la coalición Iniciativa de Cooperación de Estambul (ICI), y prestar auxilio armamentístico en la Guerra contra el Estado Islámico.

En cuanto a las garantías de los tratados internacionales y la cooperación internacional, los Emiratos Árabes Unidos han realizado un gran esfuerzo por incluir en su Constitución leyes y principios amparados por la Carta de las Naciones Unidas y la Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos, siendo miembro de la ONU y adhiriéndose a sus tratados: Convención Internacional sobre la Eliminación de todas las Formas de Discriminación Racial (1974), Convención de Derechos del Niño (1997), Convención de las Naciones Unidas contra la Delincuencia Organizada Transnacional (2007), Convención sobre la eliminación de todas las formas de discriminación de la mujer (2004); Convención de las Naciones Unidas contra la Corrupción (2006), entre otros.

También han ratificado el Estatuto de Roma de la Corte Penal Internacional, la Carta Árabe de Derechos Humanos, y convenios de organización del Trabajo. Es miembro de la OMS, OIT, FAO, UNESCO, UNICEF, OMPI, Banco Mundial y FMI. También, están vinculados por acuerdos de cooperación con más de 28 organizaciones internacionales de las Naciones Unidas llevando a cabo tareas de asesoramiento y de carácter técnico y ministerial.

Son miembros de la Liga Árabe y de la Organización de la Conferencia Islámica, reforzando y promoviendo la labor árabe en sus actividades y programas regionales.

La policía emiratí mantiene el orden público y la seguridad del Estado. El Ministerio del Interior pone los derechos humanos al frente de sus prioridades, centrándose en la justicia, igualdad, imparcialidad y protección. Los integrantes del cuerpo policial deben comprometerse a cumplir 33 normas conducta antes de tomar posesión de su puesto. El Ministerio del Interior ofrece dependencias administrativas al ciudadano para supervisar la actividad policial y adoptar las medidas necesarias. Sin embargo, existe una cierta desconfianza de los extranjeros hacia la policía. La mayor parte de denuncias proviene de ciudadanos emiratíes.

El Ministerio del Interior debe proporcionar a las misiones diplomáticas y consulares listas que incluyan datos sobre sus nacionales internados en instituciones penitenciarias.

III. SISTEMA SOCIAL

El gobierno emiratí ha promovido sociedades civiles e instituciones nacionales como la asociación de los Emiratos para los Derechos Humanos (en virtud de la Ley Federal Nº 6/1974), la Federación General de las Mujeres, Asociación de Juristas, Asociación de Sociólogos, Asociación de Periodistas, Dirección General de Protección de los Derechos Humanos adscrita a la Jefatura General de la Policía de Dubái, Fundación Benéfica de Dubái para la Atención a la Mujer y el Niño, Comisión Nacional de Lucha contra la Trata de Personas, centro de Apoyo Social de la Dirección General de la Policía de Abu Dhabi, Institución Zayed de Obras Benéficas, Media Luna Roja de los Emiratos, Institución de Desarrollo Familiar, y la Fundación Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum de Obras Benéficas y Humanitarias, o el Fondo para el Matrimonio, entre muchas otras.

Es importante destacar que el desarrollo de la participación política está siguiendo un proceso progresivo. Hasta la fecha, existen unas elecciones completas y generales para designar a la mitad de los miembros de la Asamblea Federal Nacional, con sufragio censitario, para ciudadanos emiratíes y mediante una publicación de listas.

También, la importancia de la mujer en la sociedad emiratí está creciendo gracias a las medidas legislativas y legales adoptadas por el gobierno para potenciar el papel de la mujer, mediante la membresía del Comité de Desarrollo Social del Consejo Económico y Social, que permitan otorgar oportunidades a la mujer que participe de forma activa en el desarrollo sostenible, y la integración de la mujer en sectores gubernamentales y privado-empresarial (siendo mujeres el 22,5% de la Asamblea, 2006; se espera que a partir de 2019 sea el 50% por decreto)[3], y promoviendo el alfabetismo femenino hasta igualarlo con el masculino. Sin embargo, a pesar de ser signatarios de la Convención sobre la eliminación de todas las formas de discriminación contra la mujer, en la práctica sufren discriminaciones en los trámites matrimoniales y de divorcio. Afortunadamente, se abolió la legislación emiratí que preveía el maltrato de las mujeres e hijos menores por parte del marido o padre siempre que la agresión no excediera los límites admitidos por la ley islámica. También, una vez contraído matrimonio, las mujeres deben prestar obediencia a sus maridos y ser autorizadas por ellos para ocupar un puesto laboral. Asimismo, está prohibida, bajo penas de cárcel, la convivencia entre hombres y mujeres no casados, y las relaciones sexuales fuera del matrimonio. La poligamia está presente incluso en la familia real.

Como en el resto de los países árabes, la homosexualidad está considerada un delito grave y castigada con multas, prisión y deportación en el caso de extranjeros, aunque su aplicación es muy escasa.

Los medios de comunicación juegan un rol importante en la sociedad emiratí. Están supervisados por el Consejo Nacional de Medios de Comunicación, que actúa en gran medida como órgano censor. Han alcanzado un alto nivel técnico y profesional en el sector periodístico, acogiendo en la Dubai Media City a más de mil empresas especializadas. Sin embargo, el periodismo está controlado mediante la Ley Federal sobre Prensa y Publicaciones de 1980, y Carta de Honor y la Moral de la Profesión Periodística, que han firmado los jefes de redacción. Por ejemplo, algunas noticias que pueden ser desfavorables para el Islam o el gobierno nunca serían publicadas en los periódicos nacionales, pero sí en los extranjeros (caso de Haya de Jordania). Desde 2007, mediante un decreto del Consejo de Ministros, estaba prohibido el encarcelamiento de periodistas en caso de que cometiesen errores durante el ejercicio de sus funciones profesionales. Sin embargo, dejó de aplicarse con la entrada en vigor de la Ley contra cibercriminalidad adoptada en 2012.

El gobierno se está esforzando en cumplir una mejora en las condiciones de trabajo, pues los Emiratos Árabes Unidos tienen la convicción de que el ser humano tiene derecho a disfrutar de condiciones de vida adecuadas (vivienda, horarios, medios, tribunales laborales, seguro médico, garantías protectoras en conflictos laborales a nivel cooperativo internacional…) Sin embargo, sigue vigente el sistema “Sponsor” o “Kafala”, mediante el cual un empleador ejerce el patrocinio de sus empleados. Así, existen casos en los que el sponsor retiene los pasaportes de sus empleados durante la vigencia del contrato, lo cual es ilegal, pero nunca han sido investigados y castigados por el gobierno (caso del proyecto de construcción de Saadiyat Island), a pesar de ser firmante de convenios sobre Trabajo de la ONU.

El último Informe sobre Desarrollo Humano correspondiente al año 2018, posiciona a los Emiratos Árabes Unidos en el puesto 34º de un total de 189 países. España está en el puesto 26º. El Estado ha asegurado la educación gratuita y de calidad hasta la etapa universitaria de todos los ciudadanos emiratíes, y la integración de las personas discapacitadas. Los centros universitarios y de educación superior han sido positivamente fomentados por el gobierno, como la Universidad de Emiratos Árabes Unidos, la Universidad de Zayed, o la Universidad de Nueva York en Abu Dhabi. La atención sanitaria ha mejorado considerablemente con la construcción de hospitales y clínicas, descendiendo las tasas de mortalidad y aumentando la esperanza de vida, situándose en 77.6 años (2016). El Estado destina dinero de las arcas públicas a la atención social de los sectores de población emiratí más desfavorecidos y a los mayores, viudas, huérfanos o discapacitados. También, ha procurado que los ciudadanos posean una vivienda digna, a través de instancias gubernamentales como el Ministerio de Obras Públicas, el Programa de Vivienda Zayed que ofrece préstamos hipotecarios sin intereses, Organismo de Préstamo Hipotecario de Abu Dhabi, la institución Mohammed bin Rashid para la vivienda que otorga préstamos, u el Organismo de Obras Públicas de Sharjah.

En cuanto a religión, aproximadamente el 75% de la población es de confesión musulmana. El Islam es la confesión oficial de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos. El gobierno sigue una política tolerante hacia otras religiones, y prohíbe que los no musulmanes interfieran en la educación islámica. Está prohibida la evangelización de otras religiones, y la práctica de las mismas debe realizarse en los lugares autorizados para ello.

El 3 de febrero de 2019, como inicio del Año de la Tolerancia, el Papa Francisco fue recibido con los máximos honores en Abu Dhabi por el príncipe heredero Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, el vicepresidente y emir de Dubái Mohammed bin Rashid al Maktoum, y Ahmed al Tayyeb, Gran Imán de la Universidad de Al-Azhar y principal referente teológico islámico, siendo la primera vez que la cabeza de la Iglesia Católica pisaba la Península Arábiga. Del mismo modo, el Papa ofició una misa multitudinaria en Zayed Sport City ante 150.000 personas, diciendo en su homilía: “seamos un oasis de paz”. El acontecimiento fue calificado por Mike Pompeo, secretario de Estado de los Estados Unidos, como “un momento histórico para la libertad religiosa”.

Existen Proyectos para el desarrollo de regiones remotas, que buscan modernizar las infraestructuras y servicios de aquellas zonas del Estado más alejadas de los núcleos de población. También, en virtud de la Ley Federal Nº47/1992, fue creado el Fondo para el Matrimonio, cuyo objetivo es alentar el matrimonio entre ciudadanos y ciudadanas y promover la familia, que según el gobierno es la unidad básica y pilar fundamental de la sociedad, ofreciendo subsidios financieros a aquellos ciudadanos con recursos limitados a fin de ayudarles a afrontar los gastos de boda y contribuir a lograr la estabilidad familiar de la sociedad.

IV. ECONOMÍA

Desde 1973, los Emiratos Árabes Unidos han sufrido una enorme transformación y modernización gracias a la explotación del petróleo, que representó el 80% del PIB en aquella época. En los últimos años, con el conocimiento de que en menos de 40 años el petróleo se acabará, el gobierno ha diversificado su economía hacia los servicios financieros, el turismo, comercio, transporte y la infraestructura, haciendo que el petróleo y el gas constituyan solamente un 20% del PIB nacional.

Abu Dhabi cuenta con el 90% de las reservas de petróleo y gas, seguido de Dubái, y en pequeñas cantidades en Sharjah y Ras Al Khaimah. La política petrolera del país se lleva a cabo a través del Consejo Supremo del Petróleo y la Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC). Las principales petroleras extranjeras operantes en el país son BP, Shell, ExxonMobil, Total, Petrofac o Partex, y la española CEPSA, de la cual el fondo soberano emiratí Mubadala es propietaria del 80% de la empresa.

La capacidad prestataria de las sociedades financieras se vio fuertemente afectada de forma negativa durante la crisis económica de 2008. La entrada de grandes capitales privados extranjeros se paralizó, al mismo tiempo que la inversión en los sectores de propiedad y construcción. La caída de los valores de propiedad forzó a restringir la liquidez. En 2009, las empresas locales buscaban acuerdos de moratoria con sus acreedores sobre una deuda de 26 billones de dólares. El gobierno de Abu Dhabi aportó un rescate de 5 billones para tranquilizar a los inversores internacionales.

El turismo y la infraestructura es un éxito para el país, especialmente en Dubái.[4] La construcción de atracciones turísticas de lujo como las Palm Islands y el Burj al-Arab, y el buen clima en la mayor parte del año, ha atraído a occidentales y personas de todo el mundo. Según el gobierno emiratí, la industria turística genera más dinero que el petróleo actualmente. Se están realizando grandes inversiones en energías renovables, sobre todo a través de Masdar, la empresa gubernamental, que tiene el proyecto Masdar City iniciado, la creación de una ciudad alimentada únicamente con energías renovables.

V. DINASTÍAS Y FAMILIAS REALES. LA DINASTÍA AL NAHYAN

Los Emiratos Árabes Unidos están formados por siete Emiratos y gobernados por seis familias:

Abu Dhabi: por la familia Al Nahyan (Casa Al Falahi)

Dubái: por la familia Al Maktum (Casa al Falasi)

Sharjah y Ras Al Khaimah: por la familia Al Qassimi

Ajman: por la familia Al Nuaimi

Umm Al Quwain: por la familia Al Mualla

Fujairah: por la familia Al Sharqi

Es importante conocer la terminología utilizada en el árbol genealógico de las familias reales emiratíes: “Sheikh” significa jeque, y un emir es título nobiliario que se les atribuye a los jeques. En la composición de los nombres, en primer lugar, se coloca el nombre propio del descendiente, seguido del infijo “bin” que significa “de”, más el nombre propio de su padre, y el apellido de la familia. El infijo es “bint” para las mujeres.

Por ejemplo: Sheikh Sultan bin Zayed Al Nahyan es el padre de Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan.

Es frecuente que se celebren matrimonios entre las familias gobernantes de los distintos Emiratos, entrelazando dinastías, pero siempre prevalecerá el apellido del marido sobre el de la mujer en el nombre de los hijos. Al contrario de las grandes monarquías europeas en las que el reinado se transmite de padres a hijos, en las familias emiratíes el poder se transmite primero entre hermanos, por nombramiento, y como segundo recurso, a los hijos. Estos puestos de poder deben ser ratificados por el Consejo Supremo.

La familia Al Nahyan de Abu Dhabi es una rama de la Casa Al Falahi. Ésta, es una casa real que pertenece a Bani Yas y está relacionada con la Casa Al Falasi a la que pertenece la familia Al Maktoum de Dubái. Se sabe que Bani Yas es una confederación tribal muy antigua de la región de Liwa Oasis. Existen pocos datos históricos sobre su origen exacto. La familia real Al Nahyan es increíblemente grande, ya que cada uno de los hermanos ha tenido varios hijos y con distintas mujeres. Los más importantes y recientes gobernadores de Abu Dhabi serían aquellos que han estado en el poder desde 1971, cuando los Emiratos Árabes Unidos se consolidaron como país, dejando de ser un Estado de la Tregua y protectorado británico. Son:

Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan (1918-2004): fue gobernador de Abu Dhabi desde 1966 hasta su muerte. Colaboró cercanamente con el imperio británico para mantener la integridad del territorio frente a las pretensiones expansivas de Arabia Saudita. Se le considera el Padre de la Nación y fundador de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos, junto a su homólogo Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum de Dubái. Ambos se comprometieron a formar una Federación junto a otros gobernantes una vez se realizase la retirada militar británica. Fue el primer presidente de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos, y fue reelegido cuatro veces: 1976, 1981, 1986 y 1991. Zayed se caracterizó por tener un carácter comprensivo, pacífico y de unión con los emiratos vecinos, caritativo en cuanto a donaciones, relativamente liberal y permisivo con los medios privados. Fue considerado uno de los hombres más ricos del mundo por la revista Forbes, con un patrimonio de veinte mil millones de dólares.

Murió a los 86 años y enterrado en la Gran Mezquita Sheikh Zayed de Abu Dhabi. Le sustituyó en el cargo su hijo primogénito Khalifa como gobernador y ratificado presidente de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos por el Consejo Supremo.

Tuvo seis mujeres: Hassa bint Mohammed bin Khalifa Al Nahyan, Sheikha bint Madhad Al Mashghouni, Fatima bint Mubarak Al Ketbi, Mouza bint Suhail bin Awaidah Al Khaili, Ayesha bint Ali Al Darmaki, Amna bint Salah bin Buduwa Al Darmaki, y Shamsa bint Mohammed bin Khalifa Al Nahyan; y treinta hijos, de los cuales algunos son los siguientes:

Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan (1948-presente): hijo mayor del anterior, cuya madre es Hassa bint Mohammed bin Khalifa Al Nahyan, es el actual gobernador de Abu Dhabi y presidente de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos. Su esposa es Shamsa bint Suhail Al Mazrouei, con la que tiene ocho hijos. También ocupa otros cargos: Supremo Comandante de las Fuerzas Armadas, presidente del Consejo Supremo del Petróleo, y presidente de la autoridad de inversiones de Abu Dhabi. Fue educado en la Real Academia Militar de Sandhurst de Reino Unido. Anteriormente, fue nombrado príncipe heredero de Abu Dhabi; Jefe del Departamento de Defensa de Abu Dhabi, que se convertiría en las Fuerzas Armadas de los Emiratos; Primer ministro, jefe del Gabinete de Abu Dhabi, Ministro de Defensa y Finanzas; segundo Viceprimer Ministro de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos y presidente del Consejo Ejecutivo de Abu Dhabi. El Burj Khalifa de Dubái se llama así por él, ya que ingresó el dinero necesario para concluir su construcción. Intervino militarmente en Libia enviando a la Fuerza Aérea junto con la OTAN, y prometió el apoyo al levantamiento democrático en Bahréin en 2011.

Por una filtración de WikiLeaks, el embajador estadounidense lo califica como “personaje distante y poco carismático”. Ha sido criticado por su carácter derrochador (compra del yate Azzam, escándalo de la construcción del palacio y compra de territorios en las islas Seychelles, los Papeles de Panamá y la revelación de propiedades en Londres y empresas pantalla…)

En 2014, según la versión oficial, Khalifa sufrió un derrame cerebral y fue operado quirúrgicamente. Según el gobierno, se encuentra estable, pero prácticamente ha desaparecido de la imagen pública.

Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (1961-presente): hermano de Khalifa, pero cuya madre es Fatima bint Mubarak Al Ketbi. Es el príncipe heredero de Abu Dhabi, subcomandante supremo de las Fuerzas Armadas, y encomendado para la ejecución de asuntos presidenciales, recepciones de dignatarios extranjeros y decisiones políticas debido al mal estado de salud del Presidente. También, como Khalifa, fue educado en la Real Academia Militar de Sandhurst. Ha sido Oficial de la Guardia Presidencial y piloto en la Fuerza Aérea. Está casado con Salama bint Hamdan Al Nahyan, y tiene nueve hijos.

Se ha caracterizado por su política exterior activista y en contra del extremismo islamista, y carácter caritativo (colaboración con la Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation para vacunas en Afganistán y Pakistán). Gobiernos internacionales como Francia, Singapur y Estados Unidos han invitado a Mohammed a distintos eventos y diálogos bilaterales. Incluso se ha reunido con el papa Francisco dos veces (Roma, 2016; Abu Dhabi, 2019), promoviendo el Año de la Tolerancia.

En materia económica, es el presidente del fondo soberano Mubadala y Jefe del Consejo de Abu Dhabi para el Desarrollo Económico. Ha aprobado proyectos billonarios de estimulación económica para la modernización del país en el sector energético e infraestructuras.

También, ha promovido el empoderamiento femenino, dando la bienvenida a una delegación de mujeres oficiales del Programa Militar y de Mantenimiento de la Paz para Mujeres Árabes, que se están preparando para las operaciones de Paz de las Naciones Unidas. Ha alentado la presencia de mujeres en los servicios públicos, y se ha comprometido a reunirse regularmente con las representantes femeninas de instituciones del país.

Sultan bin Zayed Al Nahyan (1955-presente): segundo hijo de Zayed. Él tiene seis hijos. Es hijo de Shamsa bint Mohammed bin Khalifa Al Nahyan. Fue educado en la escuela de Millfield y en la academia militar de Sandhurst como sus dos anteriores hermanos. Es el tercer viceprimer ministro de Emiratos Árabes Unidos, miembro del Consejo Supremo del Petróleo y miembro de la Autoridad de Inversiones de Abu Dhabi.

Hamdan bin Zayed Al Nahyan (1963-presente): quinto hijo de Zayed, cuya madre es Fatima bint Mubarak Al Ketbi. Está casado con Shamsa bint Hamdan bin Mohammed Al Nahyan. Fue educado en la Academia militar de Sandhurst. Ocupó el cargo de viceprimer ministro y ministro de Estado para Asuntos Exteriores hasta 2009. Actualmente, es el representante del emir en la región occidental de Abu Dhabi. Es licenciado en Ciencias Políticas y Administración de Empresas por la Universidad de Emiratos Árabes Unidos.

Nahyan bin Mubarak al Nahyan (1951-presente): hijo de Mubarak bin Mohammed Al Nahyan. Es el actual dirigente del Ministerio de la Tolerancia de Emiratos Árabes Unidos desde 2017. De 2016 a 2017, fue ministro de Cultura y Desarrollo del Conocimiento. También, dedicó años de su vida a la creación de centros de educación superior como la Universidad de Emiratos Árabes Unidos (1983-2013), Escuela Superior de Tecnología (1988-2013), y Universidad de Zayed (1998-2013). También, es el presidente de Warid Telecom International, una empresa de Telecomunicaciones, y el presidente del grupo bancario Abu Dhabi, Union National Bank y United Bank Limited, entre otras empresas.

Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan (1972-presente): Noveno hijo de Zayed, cuya madre es Fatima bint Mubarak Al Ketbi. Está casado con Al Yazia bint Saif bin Mohammed Al Nahyan, con la que tiene cinco hijos. Ocupa el cargo de ministro de Asuntos Exteriores y Cooperación Internacional de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos desde 2006. Es licenciado en Ciencias Políticas por la Universidad de Emiratos Árabes Unidos. Durante su mandato, los Emiratos han vivido una gran expansión en sus relaciones diplomáticas con países de América del Sur, Pacífico Sur, África y Asia, y una consolidación con los países occidentales. Es miembro del Consejo de Seguridad Nacional del país, Vicepresidente del Comité Permanente de Fronteras, Presidente del Consejo Nacional de Medios de Comunicación, Presidente de la Junta de Directores de la Fundación de los Emiratos para el Desarrollo de la Juventud, Vicepresidente de la Junta de Directores del Fondo de Abu Dhabi para el Desarrollo y Miembro de la Junta del Colegio de Defensa Nacional. Fue ministro de Información y Cultura de 1997 a 2006, y presidente de Emirates Media Incorporated.

Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan (1970-presente): octavo hijo de Zayed, cuya madre es Fatima bint Mubarak Al Ketbi. Está casado con dos mujeres, Alia bint Mohammed bin Butti Al Hamed, y Manal bint Mohammed Al Maktoum, con las que tiene seis hijos en total. Ocupa los cargos de viceprimer ministro y Ministro de Asuntos Presidenciales de Emiratos Árabes Unidos desde 2009. Es presidente del Consejo Ministerial de Servicios, de la Autoridad de Inversiones de los Emiratos y de la Autoridad de Carreras de los Emiratos. Es miembro del Consejo Supremo del Petróleo y del Consejo de Inversiones de Abu Dhabi. Se educó en Santa Barbara Community College de Estados Unidos, y se licenció en Asuntos Internacionales por la Universidad de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos. Preside el Centro Nacional de Documentación e Investigación y el Fondo de Abu Dhabi para el Desarrollo. Fue presidente del First Gulf Bank hasta 2006.

Tiene una visión empresarial desarrollada. Es el propietario del equipo de fútbol inglés Manchester City, y co-propietario del New York City de la MLS, liga de fútbol profesional estadounidense. Es miembro de la junta directiva de la Autoridad de Inversiones de Abu Dhabi, tiene una participación del 32% en Virgin Galactic, una participación del 9’1% en Daimler, y es propietario de Abu Dhabi Media Investment Corporation, por la cual es propietario del periódico inglés The National.

Saif bin Zayed Al Nahyan (1968-presente): decimosegundo hijo de Zayed, cuya madre es Mouza bint Suhail Al Khaili. ocupa el cargo de viceprimer ministro desde 2009, y Ministro del Interior desde 2004. Su función es velar por la protección interior y seguridad nacional de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos. Es graduado en Ciencias Políticas por la Universidad de Emiratos Árabes Unidos. Fue Director General de la policía de Abu Dhabi en 1995, y subsecretario del Ministerio del Interior en 1997, hasta su nombramiento como ministro.

Hazza bin Zayed Al Nahyan (1965-presente): quinto hijo de Zayed, cuya madre es Fatima bint Mubarak Al Ketbi. Está casado con Mozah bint Mohammed bin Butti Al Hamed, con la que tiene cinco hijos. Ocupa el puesto de Ministro de la Seguridad Nacional de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos, Vicepresidente del Consejo Ejecutivo del Emirato de Abu Dhabi y Presidente de la Autoridad de Identidad de los Emiratos.

Nasser bin Zayed Al Nahyan (1967-2008): hijo de Zayed, cuya madre es Amna bint Salah Al Badi. Fue presidente del Departamento de Planificación y Economía de Abu Dhabi, y fue oficial de la seguridad real. Según la versión oficial, murió a los 41 años cuando el helicóptero en el que viajaba con sus amigos se estrelló en las costas de Abu Dhabi. Fue enterrado en la mezquita Sheikh Sultan bin Zayed, y se declararon tres días de luto en todos los Emiratos Árabes Unidos.

Issa bin Zayed Al Nahyan (1970-presente): hijo de Zayed, cuya madre es Amna bint Salah Al Badi. Es un prestigioso promotor inmobiliario de la ciudad de Dubái, pero no ocupa ningún cargo político en el gobierno de Emiratos. Protagonizó un caso en el que, supuestamente, en un vídeo filtrado, él mismo torturaba a dos palestinos que eran sus socios comerciales. El juzgado emiratí declaró en sentencia firme que Issa era inocente por ser víctima de una conspiración y condenó a los palestinos a cinco años de privación de libertad por consumo de drogas, grabación, publicación y chantaje. Observadores internacionales criticaron duramente el sistema judicial emiratí y pidieron una revisión del código penal del país.

Desde mi punto de vista, y con la experiencia de haber vivido en el país, los Emiratos Árabes Unidos son un país muy desconocido para la juventud española y que tiene unas oportunidades profesionales increíbles por la demanda de trabajo extranjera, una calidad de vida muy alta a un precio asequible, pues los sueldos son bastante altos, y una Administración e instituciones fuertes y modernizadas. El choque cultural no es muy grande, pues el Estado se asegura de evadir situaciones de discriminación, a diferencia de otros países árabes. Puedo decir con total convicción que la tolerancia cultural es real. Sin embargo, los extranjeros deben tener en cuenta que no es un país occidental, y que se recomienda respetar las costumbres de la nación respecto a la vestimenta, lugares sacros y actuaciones en público, y conocer la Ley básica emiratí.

[1] Informe Nacional del Consejo de Derechos Humanos en la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas A/HRC/WG.6/3/ARE/1, 16 de septiembre de 2008.

[2] Constitución de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos de 1971.

[3] El Correo del Golfo: el 50% del Consejo Nacional Federal de EAU estará ocupado por mujeres.

[4] El Correo del Golfo: más de 8 millones de turistas visitaron Dubái en el primer semestre de 2018.

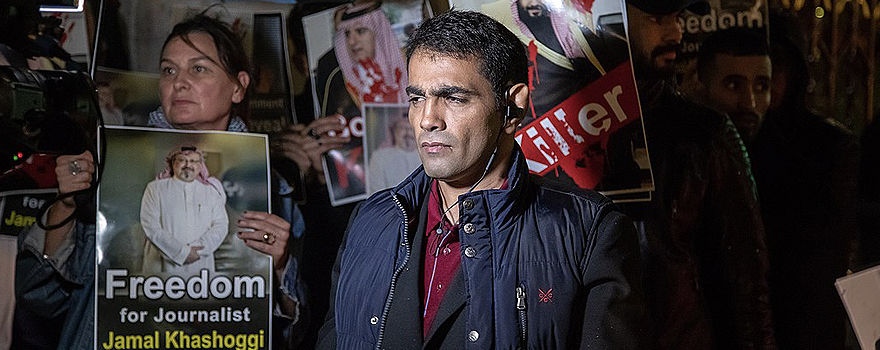

▲ Protest in London in October 2018 after the disappearance of Jamal Khashoggi [John Lubbock, Wikimedia Commons]

ANALYSIS / Naomi Moreno Cosgrove

October 2nd last year was the last time Jamal Khashoggi—a well-known journalist and critic of the Saudi government—was seen alive. The Saudi writer, United States resident and Washington Post columnist, had entered the Saudi consulate in the Turkish city of Istanbul with the aim of obtaining documentation that would certify he had divorced his previous wife, so he could remarry; but never left.

After weeks of divulging bits of information, the Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, laid out his first detailed account of the killing of the dissident journalist inside the Saudi Consulate. Eighteen days after Khashoggi disappeared, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) acknowledged that the 59-year-old writer had died after his disappearance, revealing in their investigation findings that Jamal Khashoggi died after an apparent “fist-fight” inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul; but findings were not reliable. Resultantly, the acknowledgement by the KSA of the killing in its own consulate seemed to pose more questions than answers.

Eventually, after weeks of repeated denials that it had anything to do with his disappearance, the contradictory scenes, which were the latest twists in the “fast-moving saga”, forced the kingdom to eventually acknowledge that indeed it was Saudi officials who were behind the gruesome murder thus damaging the image of the kingdom and its 33-year-old crown prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS). What had happened was that the culmination of these events, including more than a dozen Saudi officials who reportedly flew into Istanbul and entered the consulate just before Khashoggi was there, left many sceptics wondering how it was possible for MBS to not know. Hence, the world now casts doubt on the KSA’s explanation over Khashoggi’s death, especially when it comes to the shifting explanations and MBS’ role in the conspiracy.

As follows, the aim of this study is to examine the backlash Saudi Arabia’s alleged guilt has caused, in particular, regarding European state-of-affairs towards the Middle East country. To that end, I will analyse various actions taken by European countries which have engaged in the matter and the different modus operandi these have carried out in order to reject a bloodshed in which arms selling to the kingdom has become the key issue.

Since Khashoggi went missing and while Turkey promised it would expose the “naked truth” about what happened in the Saudi consulate, Western countries had been putting pressure on the KSA for it to provide facts about its ambiguous account on the journalist’s death. In a joint statement released on Sunday 21st October 2018, the United Kingdom, France and Germany said: “There remains an urgent need for clarification of exactly what happened on 2nd October – beyond the hypotheses that have been raised so far in the Saudi investigation, which need to be backed by facts to be considered credible.” What happened after the kingdom eventually revealed the truth behind the murder, was a rather different backlash. In fact, regarding post-truth reactions amongst European countries, rather divergent responses have occurred.

Terminating arms selling exports to the KSA had already been carried out by a number of countries since the kingdom launched airstrikes on Yemen in 2015; a conflict that has driven much of Yemen’s population to be victims of an atrocious famine. The truth is that arms acquisition is crucial for the KSA, one of the world’s biggest weapons importers which is heading a military coalition in order to fight a proxy war in which tens of thousands of people have died, causing a major humanitarian catastrophe. In this context, calls for more constraints have been growing particularly in Europe since the killing of the dissident journalist. These countries, which now demand transparent clarifications in contrast to the opacity in the kingdom’s already-given explanations, are threatening the KSA with suspending military supply to the kingdom.

COUNTRIES THAT HAVE CEASED ARMS SELLING

Germany

Probably one of the best examples with regards to the ceasing of arms selling—after not been pleased with Saudi state of affairs—is Germany. Following the acknowledgement of what happened to Khashoggi, German Chancellor Angela Merkel declared in a statement that she condemned his death with total sharpness, thus calling for transparency in the context of the situation, and stating that her government halted previously approved arms exports thus leaving open what would happen with those already authorised contracts, and that it wouldn’t approve any new weapons exports to the KSA: “I agree with all those who say that the, albeit already limited, arms export can’t take place in the current circumstances,” she said at a news conference.

So far this year, the KSA was the second largest customer in the German defence industry just after Algeria, as until September last year, the German federal government allocated export licenses of arms exports to the kingdom worth 416.4 million euros. Respectively, according to German Foreign Affair Minister, Heiko Maas, Germany was the fourth largest exporter of weapons to the KSA.

This is not the first time the German government has made such a vow. A clause exists in the coalition agreement signed by Germany’s governing parties earlier in 2018 which stated that no weapons exports may be approved to any country “directly” involved in the Yemeni conflict in response to the kingdom’s countless airstrikes carried out against Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in the area for several years. Yet, what is clear is that after Khashoggi’s murder, the coalition’s agreement has been exacerbated. Adding to this military sanction Germany went even further and proposed explicit sanctions to the Saudi authorities who were directly linked to the killing. As follows, by stating that “there are more questions unanswered than answered,” Maas declared that Germany has issued the ban for entering Europe’s border-free Schengen zone—in close coordination with France and Britain—against the 18 Saudi nationals who are “allegedly connected to this crime.”

Following the decision, Germany has thus become the first major US ally to challenge future arms sales in the light of Khashoggi’s case and there is thus a high likelihood that this deal suspension puts pressure on other exporters to carry out the same approach in the light of Germany’s Economy Minister, Peter Altmaier’s, call on other European Union members to take similar action, arguing that “Germany acting alone would limit the message to Riyadh.”

Norway

Following the line of the latter claim, on November 9th last year, Norway became the first country to back Germany’s decision when it announced it would freeze new licenses for arms exports to the KSA. Resultantly, in her statement, Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ine Eriksen Søreide, declared that the government had decided that in the present situation they will not give new licenses for the export of defence material or multipurpose good for military use to Saudi Arabia. According to the Søreide, this decision was taken after “a broad assessment of recent developments in Saudi Arabia and the unclear situation in Yemen.” Although Norwegian ministry spokesman declined to say whether the decision was partly motivated by the murder of the Saudi journalist, not surprisingly, Norway’s announcement came a week after its foreign minister called the Saudi ambassador to Oslo with the aim of condemning Khashoggi’s assassination. As a result, the latter seems to imply Norway’s motivations were a mix of both; the Yemeni conflict and Khashoggi’s death.

Denmark and Finland

By following a similar decision made by neighbouring Germany and Norway—despite the fact that US President Trump backed MBS, although the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had assessed that the crown prince was responsible for the order of the killing—Denmark and Finland both announced that they would also stop exporting arms to the KSA.

Emphasising on the fact that they were “now in a new situation”—after the continued deterioration of the already terrible situation in Yemen and the killing of the Saudi journalist—Danish Foreign Minister, Anders Samuelsen, stated that Denmark would proceed to cease military exports to the KSA remarking that Denmark already had very restrictive practices in this area and hoped that this decision would be able to create a “further momentum and get more European Union (EU) countries involved in the conquest to support tight implementation of the Union’s regulatory framework in this area.”

Although this ban is still less expansive compared to German measures—which include the cancelation of deals that had already been approved—Denmark’s cease of goods’ exports will likely crumble the kingdom’s strategy, especially when it comes to technology. Danish exports to the KSA, which were mainly used for both military and civilian purposes, are chiefly from BAE Systems Applied Intelligence, a subsidiary of the United Kingdom’s BAE Systems, which sold technology that allowed Intellectual Property surveillance and data analysis for use in national security and investigation of serious crimes. The suspension thus includes some dual-use technologies, a reference to materials that were purposely thought to have military applications in favour of the KSA.

On the same day Denmark carried out its decision, Finland announced they were also determined to halt arms export to Saudi Arabia. Yet, in contrast to Norway’s approach, Finnish Prime Minister, Juha Sipilä, held that, of course, the situation in Yemen lead to the decision, but that Khashoggi’s killing was “entirely behind the overall rationale”.