Breadcrumb

Blogs

[Mai’a K. Davis Cross, The Politics of Crisis in Europe. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. 2017. 248 páginas]

RESEÑA / Mª Teresa La Porte [Versión en inglés]

La principal tesis de la extensa investigación que presenta esta obra se condensa en una de sus últimas conclusiones: ‘Indeed, what the crisis over Iraq, the constitution, and the Eurozone have revealed is that even in the face of extreme adversity, and even when the easy route of freezing or rolling back integration is on the table before them, Europeans routinely choose more Europe, not less’ (p. 235). La autora justifica esta afirmación arguyendo que la percepción de crisis existencial (existential crisis) que periódicamente azota a la Unión Europea es un constructo social (social construct), iniciado y orquestado por los medios de comunicación y los líderes de opinión pública (public opinión shapers) que controlan la elaboración de las narrativas y determinan la percepción pública de los hechos. La cobertura mediática amplifica un problema, que si bien es innegable, no cuestiona la existencia de la Unión Europea. Esa visión negativa provoca en la ciudadanía lo que Cross denomina ‘integrational panic’, generando un sentimiento de catástrofe que se multiplica a través de los discursos políticos. La ausencia de ‘crisis real’ vendría demostrada por el hecho de que, tras estas aparentes catástrofes, se produce un avance constatable en integración europea y un renovado deseo de encontrar un consenso.

El libro presenta el análisis de tres ‘crisis’ recientes por las que ha atravesado la Unión Europea: la disputa en relación con la participación en la guerra de Irak (2003), el debate en torno a la Constitución Europea (2005) y la crisis económica de la euro zona (2010-12). Cada uno de los casos comprende un estudio cualitativo y cuantitativo del contenido de medios líderes internacionales, un examen de la reacción de la opinión pública y un seguimiento de la toma de decisiones políticas. A pesar de la diferencia entre los casos de estudio, la autora encuentra un patrón común a todos ellos que permite el estudio comparativo y que se desarrolla de la siguiente manera: surgimiento del conflicto que provoca el debate, reacción negativa de los instigadores sociales elaborando narrativas alarmantes, percepción de crisis existencial por parte de la ciudadanía, estado de ‘catarsis’ (catharsis) en la que se relajan las tensiones y se produce una reflexión serena sobre los acontecimientos, y, por último, la fase de resolución en la que se adoptan medidas políticas que refuerzan la integración europea (Estrategia de Seguridad Europea, 2003 (European Security Strategy); Tratado de Lisboa, 2009 (Lisbon Treaty); Pacto Fiscal Europeo, 2012 (Fiscal Compact)).

|

La Unión Europea se entiende como un proyecto en vías de desarrollo: ‘a work in progress, a project that is perennially in the middle of its evolution, with no clearly defined end goal’ (p.2). Las desavenencias entre los estados miembros, en relación con la política exterior o con el grado de integración, son propias de una iniciativa ambiciosa, que está en plena proceso de maduración y que avanza contando siempre con el parecer de todos y cada uno de sus miembros. Sin embargo, el estudio no minusvalora las dificultades reales por las que atraviesa la institución comunitaria y están presentes a lo largo de toda la investigación.

Resulta especialmente interesante el detenido seguimiento de las dinámicas sociales que genera la interpretación de las ‘crisis de existencia’ de la Unión Europea. Los procesos de elaboración de las narrativas por los medios de comunicación, el efecto multiplicador a través de los discursos de actores políticos y expertos, y la reacción de la opinión pública europea y global aportan un conocimiento sobre el impacto político del comportamiento social que debe tener mayor consideración en la disciplina de relaciones internacionales. El estudio destina una especial atención a la resolución de la crisis y al fenómeno de ‘catarsis’ que se produce como consecuencia de la reflexión política. Esta etapa comenzaría cuando se amplían las opciones y se empiezan a valorar diferentes soluciones, las élites políticas recuperan su poder de decisión y se inicia la consideración de potenciales oportunidades de generar consenso y avanzar en la integración. Como la autora remarca, la catarsis no elimina las tensiones, pero permite un debate abierto que concluye con una propuesta positiva.

Es también una contribución positiva la revisión científica del concepto de ‘crisis’ en las principales perspectivas intelectuales de la materia: la visión sistémica, la conductual o del comportamiento y la visión sociológica. Basándose en la producción anterior, la autora aporta un nuevo concepto ‘integrational panic’ que define como ‘a social overreaction to a perceived problem’.

La crítica procedente del ámbito académico, aunque no deja de subrayar el interés del enfoque del trabajo, considera insuficiente el análisis político de cada uno de los conflictos analizados y afirma que el libro no refleja bien la complejidad de los problemas a los que se enfrenta Europa. En concreto, se cuestiona si la crisis del Brexit y el surgimiento de los partidos euroescépticos no desmantelan la argumentación expuesta en estas páginas. La autora incluye un breve comentario sobre ambas cuestiones (el referéndum británico coincide con la publicación del libro) arguyendo que ambos problemas responden a un conflicto de política nacional y no europeo, pero la crítica lo considera incompleto.

En cualquier caso, la relevancia del trabajo está justificada por varios motivos. En primer lugar, su novedad: aunque las crisis por las que ha atravesado la Unión Europea han sido estudiadas con anterioridad, son muy pocos los trabajos que lo han hecho de forma comparada y concluyendo comportamientos comunes. En segundo lugar, y aunque sea una tesis discutible, el análisis del efecto de los medios de comunicación y de los líderes de opinión pública en la crisis existenciales de la UE contribuye a una valoración política del fenómeno más certera y realista. Por último, la investigación favorece una mejor gestión de estos periodos de turbulencia, permitiendo reducir los efectos desgastantes de un constante debate sobre la pervivencia de la institución dentro y fuera de Europa.

ESSAY / Andrea Pavón-Guinea [Spanish version]

-

Introduction

The recent terrorist attacks in European soil, together with the rise of the Daesh, the civil war in Syria and the refugee crisis have underlined the critical importance for European intercultural dialogues with the Islamic world, placing the interdependence of the European Union (EU) and its Southern neighborhood on the spotlight. The European Union is focusing their resources on civil society initiatives that based on soft power may contribute to radicalization prevention. Through the creation of the Anna Lindh Foundation for the Dialogue between Cultures, where all the Euro-Mediterranean partners are represented, the European Union has an unparalleled instrument for bringing peoples from both shores of the Mediterranean together and for contributing to the improvement of Euro-Mediterranean relations through people-to-people engagement.

-

Intercultural dialogue in the Euro-Mediterranean relations

The abovementioned interdependence between the European Union and the South Mediterranean basin began[1] to be regulated by the so-called Barcelona Process in 1995[2].

The Barcelona Declaration formally initiated the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (EMP), which is a multilateral framework of relations ‘based on a spirit of partnership’ that aims at turning the Mediterranean basin into an ‘area of dialogue, exchange and cooperation guaranteeing peace, stability and prosperity’. The Barcelona Process recalled one of the founding principles of the European Union: common objectives need to be addressed in a spirit of co-responsibility (Suzan, 2002). The Declaration’s goals are threefold (also known as the EMP’s three ‘baskets’): the creation of a common area of peace and stability through the reinforcement of security and political dialogues (political & security basket); the construction of a zone of shared prosperity through and economic and financial partnership (economic & financial basket); and the promotion of understanding between cultures through the exchange of civil societies – the so-called inter-cultural dialogue – (Social, cultural and human affairs basket).

More than twenty years after the Declaration, the recent events of today’s politics in the European Southern Neighborhood have further underlined the critical importance for European security of dialogues with the Islamic world in a variety of issues. If European officials had rejected Huntington’s ‘clash of civilizations’ thesis when it was first articulated, they started considering it as a plausible scenario after September 11: a scenario, however, that could be partly averted by making efforts through the third basket of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership in the form of enhanced dialogue and cultural cooperation (Gillespie, 2004).

-

Counter-radicalization through intercultural dialogue: The Anna Lindh Foundation

Emphasizing that dialogue among cultures, civilizations and religions throughout the Mediterranean Region is more necessary than ever before in order to promote understanding among them, the Euro-Mediterranean partners agreed during the 5th Euro-Mediterranean Conference of Foreign Ministers in Valencia (2002) to establish a foundation that distinctly deals with inter-cultural dialogue. This way, the Anna Lindh Foundation for the Dialogue between Cultures (ALF), based on Alexandria (Egypt), became operational in 2005. Being the first properly Euro-Mediterranean institution, it coordinates a region-wide network of over 4,000 civil society organizations belonging to the 42 UfM[3] partners.

Despite being created in 2005, the last few years have seen a dramatic growth of interest in intercultural dialogue as a means of radicalization prevention. For instance, the Mediterranean Forum of the Anna Lindh Foundation, hosted in Malta in October 2016, acknowledged the importance of intercultural dialogue in counteracting extremism. Furthermore, the outcomes of the Forum found that intercultural dialogue is already embedded in the policy discourse, evidenced by references to the Anna Lindh Foundation and its intercultural dialogue mandate in the new European Neighborhood Policy (18.11.2015) and HR Mogherini’s Strategy for International Cultural Relations.

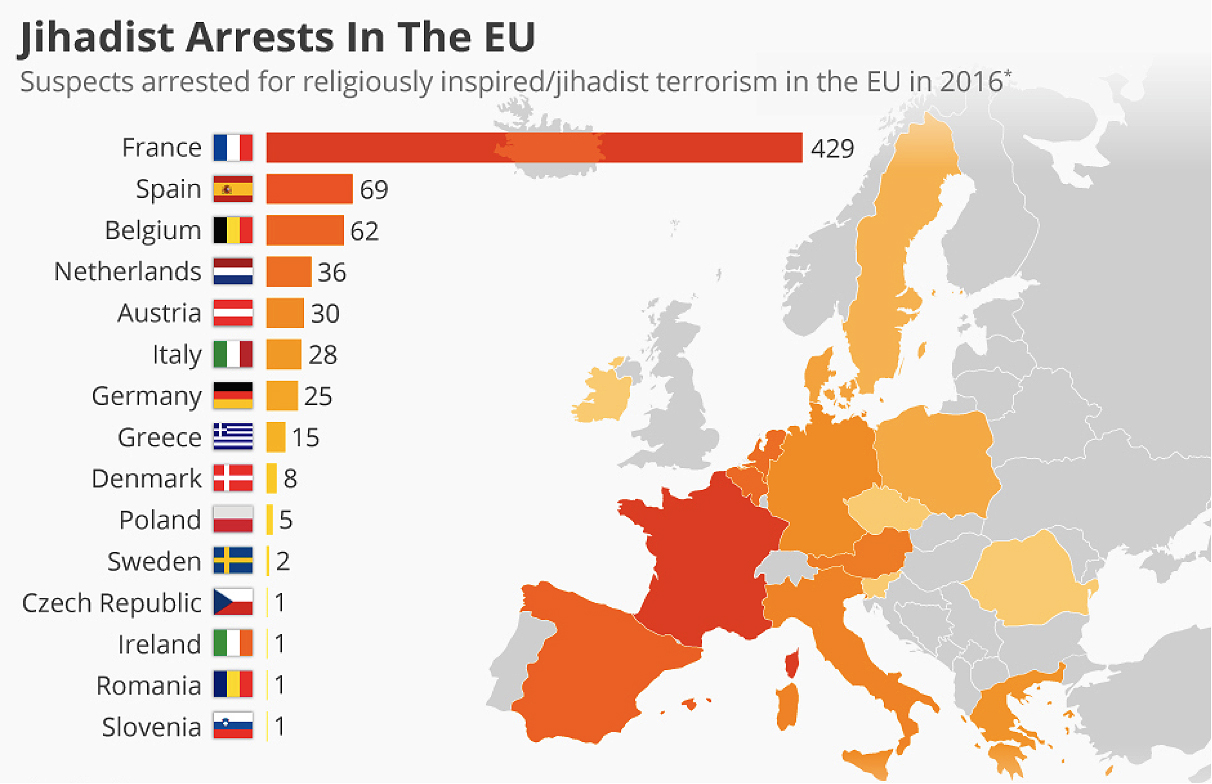

However, it has been the recent terrorist attacks in Europe the ones that have highlighted the urgent need to tackle the phenomenon of radicalization[4] that may lead to violent extremism and terrorism. In this regard, the prevention of radicalization[5] is a key part of the fight against terrorism, as was highlighted in the European Agenda on Security[6] in 2015. It is worth mentioning that the majority of the terrorist suspects implicated in those attacks were European citizens, born and raised in EU Member States, who were radicalized to commit acts of political violence. It evidences the ‘transnational dimension of Islamist terrorism’ (Kaunert and Léonard, 2011: 287) and the changing nature of the threat, whose drivers are different from, and more complex than, previous radicalization phenomena: ‘Radicalization today has different root causes, operates on the basis of different recruitment and communication techniques; it is marked by globalized and moving targets inside and outside Europe and grows in various urban contexts’[7]. The following map shows the number of Jihadi arrests in European soil in 2016.

|

Source: Europol (2016) |

Consequently, against the background of the rising prominence of the ‘clash of civilizations’ discourse in the aftermath of the 9/11, the Anna Lindh Foundation could be understood as an alternative and non-confrontational response to the US-led war on terror (Malmvig, 2007). It aims at creating ‘a space of prosperity, coexistence and peace’ through ‘restoring trust in dialogue and bridging gaps in mutual perceptions’. It thus represents the idea that encouraging understanding between cultures and exchanges between civil societies is a crucial element of any political and strategic program aimed at neighboring Mediterranean countries (Rosenthal, 2007). In other words, the creation of an area of dialogue, cooperation and exchange in the South Mediterranean is a key external relations priority for the European Union. Not only that but with the launching of the Anna Lindh Foundation, the EU recognizes that for the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership to work, dialogue between people – not just political elites – becomes essential.

This focus on civil society engagement is crucial in tackling radicalization processes, that precede the phase of violent extremism and future terrorist practices. For instance, the United Nations’ Counter-Terrorism Implementation Task Force[8] has argued that the state alone does not have all the resources necessary to counter radicalization and therefore need partners to carry out this task. Involving civil society and local communities enhances trust and social cohesion and can be a means to reach segments of society that governments may have difficulty to engage with. The European Union has also highlighted the importance of local actors, who are usually best placed to prevent and detect radicalization both in the short-term and the long-term[9].

Conclusion

Intercultural dialogue may thus be seen as a desirable tool to address the phenomenon of radicalization in the region of the South Mediterranean, where the legacies of a colonial order demand that ‘more credible interlocutors need to be found among non-governmental agents’ (Riordan, 2005: 182). The European Union will ought to abandon its existing ’donor mentality’ and move towards real partnerships and people-to-people confidence building measures (Amirah and Behr, 2013: 5), holding the assumption that practices based on dialogue and mutuality may offer a promising framework for improving the European Union’s relations towards the South Mediterranean, and particularly, for countering radicalization processes occurring both in and outside Europe.

[1] The first attempt to regulate such interdependence was the launch of the Euro-Arab Dialogue (1973-1989); conceived as a forum for dialogue between the European Community and the Arab League, their efforts nevertheless were frustrated because of the international tensions of the Gulf War and the Arab-Israeli conflict (Khader, 2015).

[2] The Euro-Mediterranean Partnership has been complemented by the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP) in 2004. Modeled on the enlargement policy, its underlying rationale is the same: “Attempting to shape the neighborhood by exporting the EU’s norms and values” (Gstöhl, 2016: 3). In response to the conflicts in the ENP regions, the rise of extremism and terrorism and the refugee flows to Europe, the ENP has been revised both in 2011 and 2015, calling for a focus on stabilization and further differentiation among the ENP countries. The ENP is based on differential bilateralism (Del Sarto and Schumacher, 2005), and abandons the prevalence of the principle of regionality that was inherent in the Barcelona Process.

[3] The Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) was created by 43 Euro-Mediterranean Heads of State and Government on 13 July 2008 at the Paris Summit for the Mediterranean. It was launched as a continuation of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (Euro-Med), also known as the Barcelona Process, which was established in 1995.

[4] Although there are different types of political extremism, this article focuses on Islamist extremism and jihadist terrorism, since violent Sunni extremists have been responsible for the largest number of terrorist attacks worldwide (Schmid, 2013). It is also worth noting that ‘a universally accepted definition of the concept of radicalization is still to be developed’ (Veldhuis and Staun, 2009: 4)

[5] Since 2004, the term ‘radicalization’ has become central to terrorism studies and counter-terrorism policy-making in order to analyze ‘homegrown’ Islamist political violence (Kundnani, 2012)

[6] The European Agenda on Security, COM (2015) 185 of 28 April 2015

[7] The prevention of radicalization leading to violent extremism, COM (2016) 379 of 14 June 2016

[8] First Report of the Working Group on Radicalization and Extremism that Lead to Terrorism: Inventory of State Programmes (2006)

[9] The prevention of radicalization leading to violent extremism, COM (2016) 379 of 14 June 2016

Bibliography

Amirah, H. and Behr, T. (2013) “The Missing Spring in the EU’s Mediterranean Policies”, Policy Paper No 70. Notre Europe – Jacques Delors Institute, February, 2013.

Council of the European Union (2002) “Presidency Conclusions for the Vth Euro-Mediterranean Conference of Foreign Ministers” (Valencia 22-23 April 2002), 8254/02 (Presse 112)

Del Sarto, R. A. and Schumacher, T. (2005): “From EMP to ENP: What’s at Stake with the European Neighborhood Policy towards the Southern Mediterranean?”, European Foreign Affairs Review, 10: 17-38

European Union (2016) “Towards an EU Strategy for International Cultural Relations, Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council” (https://ec.europa.eu/culture/policies/strategic-framework/strategy-international-cultural-relations_en).

European Commission. “Barcelona Declaration and Euro-Mediterranean Partnership”, 1995.

Gillespie, R. (2004) “Reshaping the Agenda? The International Politics of the Barcelona Process in the Aftermath of September 11”, in Jünemann, Annette Euro-Mediterranean Relations after September 11, London: Frank Cass: 20-35.

Gstöhl, S. (2016): The European Neighborhood Policy in a Comparative Perspective: Models, Challenges, Lessons (Abingdon: Routledge)

Kaunert, C. and Léonard, S. (2011) “EU Counterterrorism and the European Neighborhood Policy: An Appraisal of the Southern Dimension”, Terrorism and Political Violence, 23: 286-309

Khader, B. (2015): Europa y el mundo árabe (Icaria, Barcelona)

Kundnani, A. (2012) “Radicalization: The Journey of a Concept”, Race & Class, 54 (2): 3-25

Malmvig, H. (2007): “Security Through Intercultural Dialogue? Implications of the Securitization of Euro-Mediterranean Dialogue between Cultures”. Conceptualizing Cultural and Social Dialogue in the Euro-Mediterranean Area. London/New York: Routledge: 71-87

Riordan, S. (2005): “Dialogue-Based Public Diplomacy: A New Foreign Policy Paradigm?”, in Melissen, Jan, The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations, Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan: 180-193.

Rosenthal, G. (2007): “Preface: The Importance of Conceptualizing Cultural and Social Co-operation in the Euro-Mediterranean Area”. Conceptualizing Cultural and Social Dialogue in the Euro-Mediterranean Area. London/New York: Routledge: 1-3.

Schmid, A. (2013) “Radicalization, De-Radicalization, Counter-Radicalization: A Conceptual Discussion and Literature Review”, ICCT Research Paper, March 2013

Suzan, B. (2002): “The Barcelona Process and the European Approach to Fighting Terrorism”. Brookings Institute [online] https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-barcelona-process-and-the-european-approach-to-fighting-terrorism/ [accessed 14 August 2017]

Veldhuis, T. and Staun, J. (2009) Islamist Radicalisation: A Root Cause Model (The Hague: Clingendael)

ENSAYO / Andrea Pavón-Guinea [Versión en inglés]

-

Introducción

La combinación de ataques terroristas en suelo europeo, el surgimiento del Estado Islámico, la guerra civil siria y la crisis de los refugiados han puesto de manifiesto la importancia del diálogo intercultural entre la Unión Europea y el mundo islámico. En este contexto de guerra asimétrica y retos no tradicionales de seguridad, la Unión Europea está centrando sus recursos en iniciativas de la sociedad civil basadas en poder blando que puedan contribuir a la prevención de la radicalización. Mediante la creación de la Fundación Anna Lindh para el desarrollo intercultural, la Unión Europea dispone de un instrumento sin igual para acercar a las sociedades civiles de ambas orillas del Mediterráneo y contribuir a la mejora de las relaciones Euro-Mediterráneas.

-

Las relaciones Euro-Mediterráneas y el diálogo intercultural

Las relaciones entre la Unión Europea y el Mediterráneo Sur empezaron[1] a ser reguladas formalmente con la creación del Proceso de Barcelona en 1995[2].

La Declaración de Barcelona daría lugar a la creación de la Asociación Euro-Mediterránea; un foro de relaciones multilaterales que, ‘basadas en un espíritu de asociación’, pretende convertir la cuenca mediterránea en un ‘área de diálogo, intercambio y cooperación que garantice la paz, la estabilidad y la prosperidad’. El Proceso de Barcelona traería así a colación uno de los principios fundadores de la Unión Europea, aquel que llama a alcanzar los objetivos comunes mediante un espíritu de corresponsabilidad (Suzan, 2002). La Declaración persigue tres objetivos fundamentales: en primer lugar, la creación de un área común de paz y estabilidad a través del refuerzo de la seguridad y del diálogo político (sería la llamada ‘cesta política’); en segundo lugar, la construcción de una zona de prosperidad compartida a través de la asociación económica y financiera (‘cesta económica y financiera’); y, en tercer lugar, la promoción del entendimiento entre las cultures a través de las redes de la sociedad civil: el llamado diálogo intercultural (cesta de ‘asuntos sociales, culturales y humanos’).

Más de veinte años después de la Declaración, los reclamos de la política actual en el Mediterráneo Sur subrayan la importancia del desarrollo del diálogo intercultural para la seguridad europea. Aunque los políticos europeos rechazaran la tesis del choque de civilizaciones de Huntington cuando ésta fue articulada por primera vez, se convertiría, sin embargo, en un escenario a considerar después de los ataques del once de septiembre: un escenario, sin embargo, que podría evitarse mediante la cooperación en el ámbito de la ‘tercera cesta’ de la Asociación Euro-Mediterránea, es decir, a través del diálogo reforzado y la cooperación cultural (Gillespie, 2004).

-

Luchando contra la radicalización a través del diálogo intercultural: La Fundación Anna Lindh

Así pues, haciendo hincapié en que el diálogo entre culturas, civilizaciones y religiones en toda la región Euro-Mediterránea es más necesario que nunca para promover el entendimiento mutuo, los socios Euro-Mediterráneos acordaron durante la quinta conferencia Euro-Mediterránea de Ministros de Asuntos Exteriores, en Valencia en 2002, establecer una fundación cuyo objetivo fuese el desarrollo del diálogo intercultural. De esta manera nace la Fundación Anna Lindh para el Diálogo entre Cultures que, con sede en Alejandría, comenzaría a funcionar en el año 2005.

Cabe destacar que Anna Lindh es única en su representación y configuración, pues reúne a todos los socios Euro-Mediterráneos en la promoción del diálogo intercultural, que es su único objetivo. Para ello, se basa en la coordinación de una red regional de más de 4.000 organizaciones de la sociedad civil, tanto europeas, como mediterráneas.

A pesar de que lleve en funcionamiento ya más de diez años, su trabajo se centra en la actualidad en el desarrollo del diálogo intercultural con el fin de prevenir la radicalización. Este énfasis ha sido continuamente puesto de manifiesto en los últimos años, por ejemplo, en el Foro Mediterráneo de la Fundación Anna Lindh, celebrado en Malta en octubre de 2016, su mandato en el diálogo intercultural contenido en la nueva Política Europea de Vecindad (18.11.2015) y en la estrategia de la Alta Representante Mogherini para la promoción de la cultura en las relaciones internacionales.

Sin embargo, han sido los recientes ataques terroristas en Europa los que han resaltado la necesidad urgente de abordar el fenómeno de la radicalización[3], que, en última instancia, puede llegar a conducir al extremismo violento y al terrorismo. En este sentido, la prevención de la radicalización[4] es una pieza clave en la lucha contra el terrorismo, tal y como ha sido puesto de manifiesto en la Agenda Europea de Seguridad en 2015[5]. Esto es así porque la mayoría de los terroristas sospechosos de haber atentado en suelo europeo son ciudadanos europeos, nacidos y creados en estados miembros de la Unión Europea, donde han experimentado procesos de radicalización que culminarían en actos de violencia terrorista. Este hecho evidencia ‘la dimensión transnacional del terrorismo islamista’ (Kaunert y Léonard, 2011: 287), así como la naturaleza cambiante de la amenaza, cuyos motores son diferentes y más complejos que previos procesos de radicalización: ‘La radicalización de hoy tiene diferentes fundamentos, opera sobre la base de diferentes técnicas de reclutamiento y comunicación y está marcada por objetivos globalizados y móviles dentro y fuera de Europa, creciendo en diversos contextos urbanos’[6]. El siguiente mapa muestra el número de arrestos por sospecha de terrorismo yihadista en Europa en 2016.

|

Fuente: Europol (2016) |

En consecuencia, la Fundación Anna Lindh puede entenderse como una respuesta alternativa y no conflictiva al discurso del choque de civilizaciones y la guerra contra el terrorismo liderada por Estados Unidos (Malmvig, 2007). Su objetivo principal que es el de crear ‘un espacio de prosperidad, convivencia y paz’ mediante ‘la restauración de la confianza en el diálogo y la reducción de los estereotipos’ se basa en la importancia otorgada por la Unión Europea al desarrollo del diálogo intercultural entre civilizaciones como elemento crucial de cualquier programa político y estratégico dirigido a los países mediterráneos vecinos (Rosenthal, 2007). Dicho de otro modo, la creación de un área de diálogo, cooperación e intercambio en el sur del Mediterráneo es una prioridad clave de la política exterior de la Unión Europea. Además, con la creación de la Fundación Anna Lindh, la Unión Europea está reconociendo que para que la Asociación Euro-Mediterránea funcione, el diálogo entre las organizaciones de la sociedad civil, y no solo entre las elites políticas, es esencial.

Así pues, Anna Lindh, como organización basada en red de redes de la sociedad civil, se vuelve instrumento crucial para abordar la prevención de la radicalización. En esta línea, el grupo de trabajo de implementación de la lucha contra el terrorismo de Naciones Unidas[7] ha argumentado que el Estado por sí solo no cuenta con los recursos necesarios para luchar contra la radicalización terrorista, y, por lo tanto, necesita cooperar con socios de otra naturaleza para llevar a cabo esta tarea. La involucración de la sociedad civil y las comunidades locales serviría así para aumentar la confianza y la cohesión social, llegando incluso a ser un medio para llegar a ciertos segmentos de la sociedad con los que los gobiernos tendrían dificultades para interactuar. La naturaleza de los actores locales, tal y como ha resaltado la Unión Europea mediante la creación de la Fundación Anna Lindh, sería la más acertada para prevenir y detectar la radicalización tanto a corto como a largo plazo[8].

Conclusión

De esta forma, el diálogo intercultural constituye una herramienta para abordar el fenómeno de la radicalización en la región del Mediterráneo Sur, donde los legados de un pasado colonial exigen que ‘se encuentren interlocutores más creíbles entre las organizaciones no gubernamentales’ (Riordan, 2005: 182). Con el objetivo de prevenir la radicalización terrorista dentro y fuera de Europa, y asumiendo que prácticas basadas en el diálogo y la mutualidad pueden ofrecer un marco adecuado para el desarrollo y mejora de las relaciones Euro-Mediterráneas, la Unión Europea debería avanzar hacia asociaciones reales dirigidas hacia el fomento de la confianza entre las personas y rechazar cualquier programa de acción unilateral que suponga una reproducción del discurso del choque de civilizaciones (Amirah y Behr, 2013: 5).

[1] Previamente a la Declaración de Barcelona se intentó regular la cooperación Euro-Mediterránea mediante el Diálogo Euro-Árabe (1973-1989); sin embargo, aunque concebido como un foro de diálogo entre la entonces Comunidad Económica Europea y la Liga Árabe, las tensiones de la Guerra del Golfo terminarían frustrando su trabajo (Khader, 2015).

[2] La Asociación Euro-Mediterránea se complementaría con la Política Europea de Vecindad (PEV) en 2004. Basada en la política europea de ampliación, su lógica subyacente es la misma: “Intentar exportar las normas y valores de la Unión Europea a sus vecinos” (Gsthöl, 2016: 3). En respuesta a los conflictos en las regiones del Mediterráneo Sur, el aumento del extremismo y el terrorismo y la crisis de los refugiados en Europa, la PEV ha sufrido dos importantes revisiones, una en 2011 y otra en 2015, perfilando un enfoque más diferenciado entre los países de la PEV para conseguir una mayor estabilización de la zona. La PEV se basa en un bilateralismo diferencial (Del Sarto y Schumacher, 2005) y abandona la prevalencia del principio multilateral y regional inherente al Proceso de Barcelona.

[3] Aunque se pueden diferenciar varios tipos de extremismo político, esta nota se centra en el extremismo islamista y el terrorismo yihadista, pues es el extremismo suní el que ha sido responsable del mayor número de ataques terroristas en el mundo (Schmid, 2013). Cabe destacar también en este aspecto que aún no existe una definición universalmente válida del concepto de ‘radicalización’ (Veldhuis y Staun 2009).

[4] Since 2004, the term ‘radicalization’ has become central to terrorism studies and counter-terrorism policy-making in order to analyze ‘homegrown’ Islamist political violence (Kundnani, 2012).

[5] The European Agenda on Security, COM (2015) 185 of 28 April 2015.

[6] The prevention of radicalization leading to violent extremism, COM (2016) 379 of 14 June 2016

[7] First Report of the Working Group on Radicalization and Extremism that Lead to Terrorism: Inventory of State Programmes (2006)

[8] The prevention of radicalization leading to violent extremism, COM (2016) 379 of 14 June 2016

Bibliografía

Amirah, H. and Behr, T. (2013) “The Missing Spring in the EU’s Mediterranean Policies”, Policy Paper No 70. Notre Europe – Jacques Delors Institute, February, 2013.

Council of the European Union (2002) “Presidency Conclusions for the Vth Euro-Mediterranean Conference of Foreign Ministers” (Valencia 22-23 April 2002), 8254/02 (Presse 112)

Del Sarto, R. A. and Schumacher, T. (2005): “From EMP to ENP: What’s at Stake with the European Neighborhood Policy towards the Southern Mediterranean?”, European Foreign Affairs Review, 10: 17-38

European Union (2016) “Towards an EU Strategy for International Cultural Relations, Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council” (https://ec.europa.eu/culture/policies/strategic-framework/strategy-international-cultural-relations_en).

European Commission. “Barcelona Declaration and Euro-Mediterranean Partnership”, 1995.

Gillespie, R. (2004) “Reshaping the Agenda? The International Politics of the Barcelona Process in the Aftermath of September 11”, in Jünemann, Annette Euro-Mediterranean Relations after September 11, London: Frank Cass: 20-35.

Gstöhl, S. (2016): The European Neighborhood Policy in a Comparative Perspective: Models, Challenges, Lessons (Abingdon: Routledge)

Kaunert, C. and Léonard, S. (2011) “EU Counterterrorism and the European Neighborhood Policy: An Appraisal of the Southern Dimension”, Terrorism and Political Violence, 23: 286-309

Khader, B. (2015): Europa y el mundo árabe (Icaria, Barcelona)

Kundnani, A. (2012) “Radicalization: The Journey of a Concept”, Race & Class, 54 (2): 3-25

Malmvig, H. (2007): “Security Through Intercultural Dialogue? Implications of the Securitization of Euro-Mediterranean Dialogue between Cultures”. Conceptualizing Cultural and Social Dialogue in the Euro-Mediterranean Area. London/New York: Routledge: 71-87

Riordan, S. (2005): “Dialogue-Based Public Diplomacy: A New Foreign Policy Paradigm?”, in Melissen, Jan, The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations, Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan: 180-193.

Rosenthal, G. (2007): “Preface: The Importance of Conceptualizing Cultural and Social Co-operation in the Euro-Mediterranean Area”. Conceptualizing Cultural and Social Dialogue in the Euro-Mediterranean Area. London/New York: Routledge: 1-3.

Schmid, A. (2013) “Radicalization, De-Radicalization, Counter-Radicalization: A Conceptual Discussion and Literature Review”, ICCT Research Paper, March 2013

Suzan, B. (2002): “The Barcelona Process and the European Approach to Fighting Terrorism”. Brookings Institute [online] https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-barcelona-process-and-the-european-approach-to-fighting-terrorism/ [accessed 14 August 2017]

Veldhuis, T. and Staun, J. (2009) Islamist Radicalisation: A Root Cause Model (The Hague: Clingendael)

High levels of corruption in public works projects and impunity from justice in the Latin American region continue to challenge attempts to successfully eradicate fraud in government dealings

Odebrecht, one of the most important construction and engineering companies in Brazil, confessed to offering numerous bribes to political leaders, political parties and public officials. Its major aim was to obtain contracts for major public infrastructure projects within the region. The investigation has revealed a complex network of bribery that has become one of the largest corruption scandals in Latin American history. The notable budget boosts in the region, thanks to commodities’ “golden decade,” occurred within a weak precedent for the Rule of Law and therefore lax anti-corruption measures permitted widespread illicit profits for major government contractors and inflated costs for tax payers.

ARTICLE / Ximena Barria [Spanish version]

Odebrecht is a Brazilian conglomerate that through several operational headquarters conducts businesses in multiple industries. It dedicates to areas such as engineering, construction, infrastructure and energy. Its headquarters is located in Brazil in the city of Salvador Bahía. The company operates in 27 countries of Latin-America, Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Throughout the years, Odebrecht has concluded contracts with governments to build public works, with the majority of their projects in the Latin-American region.

In 2016, United States Department of Justice published allegations which detailed evidence of the company bribing public officials in twelve different countries, ten of them in Latin America: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Peru, the Dominican Republic and Venezuela. As a result, a full investigation was lanunched after Odebrecht´s senior executives confessed to bribery once discovered.

The corporation granted millions of dollars to local public officials from the countries previously mentioned, in exchange for obtaining public contracts to gain benefits from the projects constructed. Its purpose was to obtain a competitive advantage which permitted them to retain local governmental business in different countries.

In order to cover up illegal transactions, Odebrecht created fictitious, anonymous societies in such places as Belize, the Virgin Islands and Brazil. The company elaborated a secret financial structure to camouflage its payments. The investigation of the United States Department of Justice estimated that the bribes accounted a total of $788 million dollars. Utilizing this illegal method, and contrary to every political and business code of ethics, the company signed one hundred projects generating $3.336 billion dollars in profits.

A weak judicial branch

This issue, also known as the Odebrecht Case, has created major divisions within Latin American societies. Its citizens consider that these acts should not remain unpunished, as countries need a stronger judicial branch to cement a strong and respected Rule of Law.

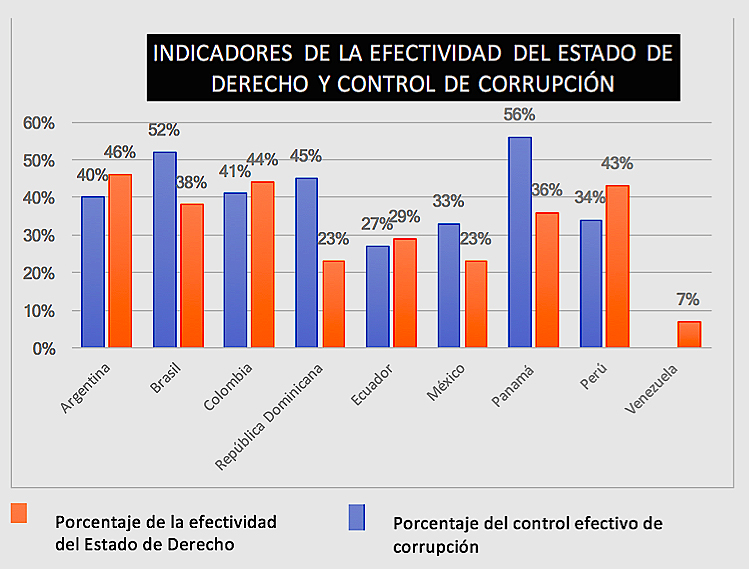

According to World Bank indicators, none of these ten Latin American countries impacted by this network of bribes hold 60% or more of the standard efficacy of the Rule of Law and control of corruption. Hence, this explains the how the construction company was able to successfully bribe politicians.

|

Worl Bank, 2016 |

The judicial independence and its efficacy are essential for the resolution of acts with these characteristics. The correct exercise of justice moulds an appropriate Rule of Law, preventing that illegal acts or other political decisions the could infringe upon it. Contrary to this ideal configuration, the countries who were involved in the Odebrecht case, do not possess optimal judicial independence.

Thus, according to the Global Competiveness Report for 2017-2018, the majority of the countries affected obtained a low score with respect to the independence of their courts. These figures indicate that the countries lack of an effective judicial system to judge the alleged suspects involved in this case. With the case of Panama and the Dominican Republic, they ranked in the places 120 and 127 respectively, according to the judicial independence of a list of 137 countries.

One of the problems suffered by the Judicial Branch of the Republic of Panama is that it has high number of pending cases awaiting trial at the Supreme Court of Justice. This congestion makes it difficult for the supreme court to work effectively. The high number of processed cases doubled between 2013 and 2016, as the Criminal Chamber of the Court processed 329 cases in 2013 and in 2016 they processed 857. Although the Panamanian Judicial Branch has expanded its budget, this has not represented a qualitative increase in its functions. These difficulties could explain the decision of the court to reject an extension of the Odebrecht investigations, although this may imply some impunity. In 2016, there were only two detainees in the Odebrecht case. In 2017, of the 43 defendants who could be involved in the acceptance of bribes valued at $60 million dollars, only 32 were prosecuted.

The Dominican Republic also faces a similar situation. According to a 2016 survey, only 38% of Dominican citizens trust their justice system. The low percentage may be a result of the fact that the Supreme Court judges who were elected are active members of political parties, something that obscures the credibility of justice and its independence. In 2016, Dominican courts only prosecuted one person related to the Odebrecht case, whereas the US Supreme Court estimated that the Brazilian company had given 92 million dollars in Dominican political bribes, one of the highest amounts outside of Brazil. In 2017, the Supreme Court of the Dominican Republic ordered the release of 9 of 10 suspects implicated in the case due to insufficient evidence.

The need for improved coordination and reform

In October 2017, public prosecutors from Latin America met in Panama City to share information on money laundering, especially related to the Odebrecht case. The officials expressed the need to not leave any case unpunished, in order to solve one of the biggest political, economic and judicial problems in the region. Some prosecutors reported having suffered threats in their investigations. The meeting was valued in a positive way, since it highlighted the need in for greater fiscal coordination and legislative harmony in Latin America. However, it is important to note that the Dominican Republic was absent from that meeting.

All awareness of the public ministries of Latin America is essential in view of the correlation observed among the countries affected by the Odebrecht bribes and their poor position in the indices provided by different international organizations and research centers. The ineffective Rule of Law shows in the lack of control over corrupt companies like Odebrecht, where they succeeded in their bribery policy to obtain a competitive advantage.

The shortcomings of the judicial systems in countries such as Panama and the Dominican Republic make it possible for public officials to go unpunished for the crimes they committed. In addition, the Odebrecht case has a great impact in the region, and could still impede the judicial process if effective reforms are not taken in each country.

La alta corrupción e impunidad en la región dificultan la erradicación de sobornos millonarios en las contratas públicas

La confesión de la compañía de construcción e ingeniería Odebrecht, una de las más importantes de Brasil, de haber entregado elevadas sumas como sobornos a dirigentes políticos, partidos y funcionarios públicos para la adjudicación de obras en diversos países de la región ha supuesto el mayor escándalo de corrupción en la historia de Latinoamérica. El notable incremento presupuestario durante la “década de oro” de las materias primas ocurrió en un marco de escasa mejora de la efectividad del Estado de Derecho y del control de la corrupción, eso propició que se produjeran elevados desvíos ilícitos en las contratas públicas.

ARTÍCULO / Ximena Barría [Versión en inglés]

Odebrecht es una compañía brasileña que través de varias sedes operativas conduce negocios en múltiples industrias. Se dedica a áreas como ingeniería, construcción, infraestructura y energía, entre otras. Su sede principal, en Brasil, está ubicada en la ciudad de Salvador de Bahía. La empresa opera en 27 países, de Latinoamérica, África, Europa y Oriente Medio. A lo largo de los años, la constructora ha participado en contratos de obras públicas de la mayor parte de los países latinoamericanos.

En 2016, el Departamento de Justicia de Estados Unidos publicó una investigación que denunciaba que la compañía brasileña había sobornado a funcionarios públicos de doce países, diez de ellos latinoamericanos: Argentina, Brasil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, México, Panamá, Perú, República Dominicana y Venezuela. La investigación se desarrolló a partir de la confesión hecha por los propios máximos ejecutivos de Odebrecht una vez descubiertos.

La compañía entregaba a los funcionarios de esos países millones de dólares a cambio de obtener contratos de obras públicas y beneficiarse del pago por su realización. La empresa acordaba entregar millones de dólares a partidos políticos, funcionarios públicos, candidatos públicos o personas relacionadas con el Gobierno. Su fin era tener una ventaja competitiva que le permitiera retener negocios públicos en diferentes países.

A fin de encubrir dichos movimientos ilícitos de capitales, la empresa creaba sociedades anónimas ficticias en lugares como Belice, las Islas Vírgenes y Brasil. La empresa elaboró una estructura financiera secreta para encubrir estos pagos. La investigación del Departamento de Justicia de Estados Unidos estableció que los sobornos en los países mencionados alcanzaron un total de 788 millones de dólares (casi la mitad solo en Brasil). Utilizando este método ilegal, contrario a toda ética empresarial y política, Odebrecht logró el encargo de más de cien proyectos, cuya realización le generó unos beneficios de 3.336 millones de dólares.

Falta de un poder judicial efectivo

Este asunto, conocido como caso Odebrecht, ha creado consternación en las sociedades latinoamericanas. Sus ciudadanos consideran que para que actos de este tipo no queden impunes, los países deben tener una mayor eficiencia en el ámbito judicial y dar pasos más acelerados hacia un verdadero Estado de Derecho.

De acuerdo con indicadores del Banco Mundial, ninguno de los diez países latinoamericanos afectados por esta red de sobornos llega al 60% de efectividad del Estado de Derecho y de control de la corrupción. Eso explicaría el éxito de la constructora brasileña en su política de coimas.

|

Fuente: Banco Mundial, 2016 |

La independencia judicial y su efectividad es esencial para la resolución de hechos de estas características. El correcto ejercicio de la Justicia moldea un apropiado Estado de Derecho, previniendo que ocurran actos ilícitos u otras decisiones políticas que puedan vulnerarlo. A pesar de que esto es lo ideal, los países involucrados en el caso Odebrecht no cumplen con cabalidad esta debida independencia judicial.

En efecto, según el Reporte de Competitividad Global para 2017-2018, la mayoría de los países afectados obtienen una baja nota respecto a la independencia de sus tribunales, lo que indica que carecen de un poder judicial efectivo para juzgar a los presuntos involucrados en este caso. Así ocurre, por ejemplo, con Panamá y con la República Dominicana, situados en los puestos 120 y 127, respectivamente, en cuanto a independencia judicial, de una lista de 137 países.

Uno de los problemas que padece el Órgano Judicial de la República de Panamá es el alto número de expedientes que maneja la Corte Suprema de Justicia. Esa congestión dificulta que la Corte Suprema pueda trabajar de manera efectiva. La alta cifra de expedientes procesados se dobló entre 2013 y 2016: la Sala Penal de la Corte procesó 329 expedientes en 2013; en 2016 fueron 857. Aunque el Órgano Judicial panameño ha mejorado su presupuesto, eso no ha representado un aumento cualitativo en sus funciones. Esas dificultades podrían explicar la decisión de la Corte de rechazar una extensión de la investigación, aunque ello pueda significar cierta impunidad. En 2016 solo hubo dos detenidos por el caso Odebrecht. En 2017, de los 43 imputados que podrían estar involucrados en la aceptación de sobornos valorados en 60 millones de dólares, solo 32 fueron procesados.

La República Dominicana también se encuentra en una situación parecida. Según una encuesta de 2016, solo el 38% de los dominicanos confían en la institución judicial. A ese bajo porcentaje puede haber contribuido el hecho de que para ejercer de jueces de la Corte Suprema fueron elegidos miembros activos de los partidos políticos, algo que opaca la credibilidad de la Justicia y su independencia. En 2016, los tribunales dominicanos solo indagaron sobre una persona, cuando la Corte Suprema estadounidense estimaba que la empresa brasileña había dado 92 millones de dólares en sobornos políticos, uno de los montos más elevados fuera de Brasil. En 2017, la Suprema Corte de la Republica Dominicana ordenó la excarcelación de 9 de 10 presuntos implicados en el caso por insuficiencia de pruebas.

Necesidad de mayor coordinación y reforma

En octubre de 2017, fiscales públicos de Latinoamérica se reunieron en Ciudad de Panamá para compartir información sobre blanqueo de capitales, especialmente en relación al caso Odebrecht. Los funcionarios expresaron la necesidad de no dejar ningún caso impune, para contribuir con ello a resolver uno de los mayores problemas políticos, económicos y judiciales de la región. Algunos fiscales reportaron haber sufrido amenazas en sus investigaciones. Todos valoraron de manera positiva el encuentro, ya que con él ponían de relevancia la necesidad en Latinoamérica de una mayor coordinación fiscal y armonía legislativa. No obstante, es importante destacar que la República Dominicana estuvo ausente de esa reunión.

Toda concienciación de los ministerios públicos de Latinoamérica es esencial ante la correlación observada entre los países afectados por los sobornos de Odebrecht y su deficiente posición en índices proporcionados por diferentes organizaciones internacionales y centros de investigación. El inefectivo Estado de Derecho y la falta de control de la corrupción facultan que empresas como Odebrecht puedan triunfar en su política de sobornos para obtener una ventaja competitiva.

Las carencias de los sistemas judiciales en países como Panamá y República Dominicana, en concreto, pueden hacer posible que funcionarios públicos queden impunes de los delitos cometidos. Además, el caso Odebrecht, de gran magnitud en la región, podría congestionar aún la actividad judicial si no se hacen reformas efectivas en cada país.

The constant expansion of soy production within the MERCOSUR countries exceeds 50% of total world production

While many typically associate South American commodities with hydrocarbons and minerals, soy or soybean is the other great commodity of the region. Today, soy is the agricultural product with the highest commercial growth rate in the world. China and India lead world consumption of this oleaginous plant and its byproducts, thus making South America a strategic supplier. Soy profitability has encouraged the expansion of crop production, especially in Brazil and Argentina, as well as in Paraguay, Bolivia and Uruguay. However, such expansion comes at an environmental cost; such as recent deforestation in the Amazon and the Gran Chaco.

ARTICLE / Daniel Andrés Llonch [Spanish version]

Soy has been cultivated in Asian civilizations for thousands of years; today its cultivation is also widespread in other parts of the world. It has become the most important oilseed for human consumption and animal feed. Of great nutritional properties, due to its high protein content, soybeans are sold both in grain and in their oil and flour derivatives.

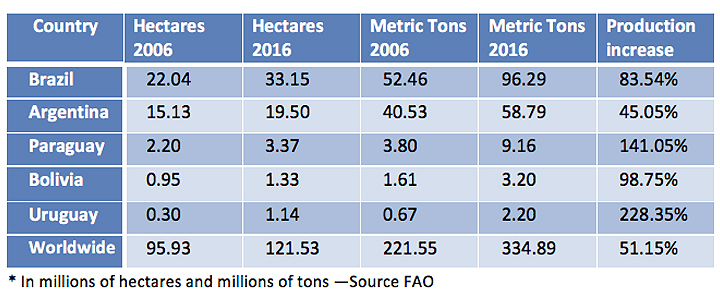

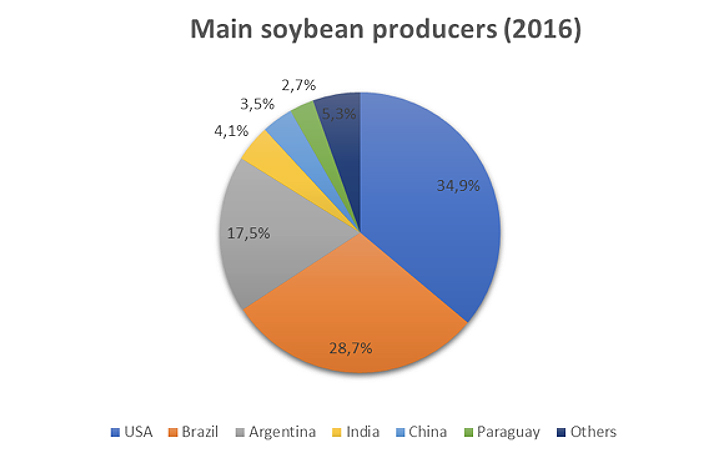

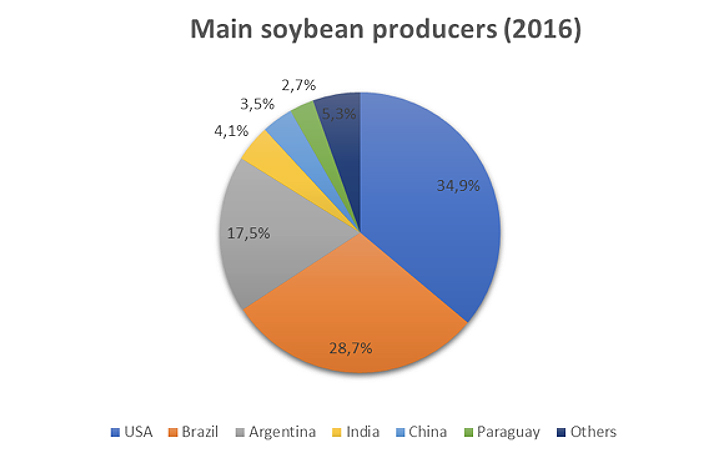

Among the eleven largest soybean producers, five are in South America: Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia and Uruguay. In 2016, these countries were the origin of 50.6% of world production, whose total reached 334.8 million tons, according to FAO data. The first producer was the United States (34.9% of world production), followed by Brazil (28.7%) and Argentina (17.5%). India and China follow the list, although what is significant about this last country is its large consumption, which in 2016 forced it to import 83.2 million tons. Much of these import needs are covered from South America. Furthermore, the South American production focuses on the Mercosur nations (in addition to Brazil and Argentina, also Paraguay and Uruguay) and Bolivia.

The strong international demand and the high relative profitability of soybean in recent years has fueled the expansion of the cultivation of this plant in the Mercosur region. The price boom for raw materials, which also involved soy, led to benefits that were directed to the acquisition of new land and equipment, which allowed producers to increase their scale and efficiency.

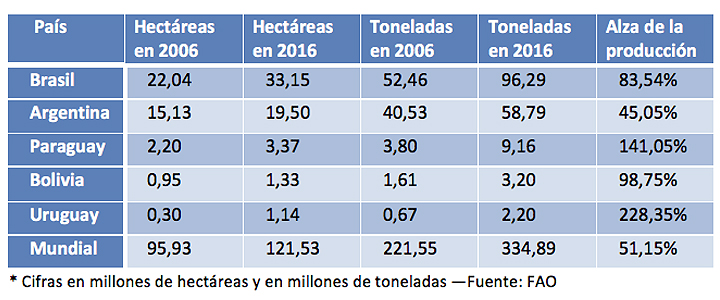

In Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Paraguay the area planted with soybeans represents the majority (it constitutes more than 50% of the total area sown with the five most important crops in each country). If we add Uruguay, where soybean has enjoyed a later expansion, we have that the production of these five South American countries has gone from 99 million tons in 2006 to 169.7 million in 2016, which constitutes a rise of 71%. , 2% (Brazil and Bolivia have almost doubled their production, somewhat exceeded by Paraguay and Uruguay, where it has tripled). In the decade, this South American area has gone from contributing 44.7% of world production to 50.6%. At that time, the cultivated area increased from 40.6 million hectares to 58.4 million.

|

Countries

As the second largest producer of soybeans in the world, Brazil reached 96.2 million tons in 2016 (28.7% of the world total), with a cultivation area of 33.1 million hectares. Its production has been in a constant increasement, so that in the last decade the volume of the harvest has increased by 83.5%. The jump has been especially notable in the last four years, in which Brazil and Argentina have experienced the highest growth rate of the crop, with an annual average of 936,000 and 878,000 hectares, respectively, according to the United States Department of Agriculture. (USDA).

Argentina is the second largest producer of Mercosur, with 58.7 million tons (17.5% of world production) and a cultivated area of 19.5 million hectares. Soybeans began to be planted in Argentina in the mid-70s, and in less than 40 years it has had an unprecedented advance. This crop occupies 63% of the areas of the country planted with the five most important crops, compared to 28% of the area occupied by corn and wheat.

Paraguay, for its part, had a harvest of 9.1 million tons of soybeans in 2016 (2.7% of world production). In recent seasons, soy production has increased as more land is allocated for cultivation. According to the USDA, in the last two decades, the land dedicated to the cultivation of soybeans has constantly increased by 6% annually. Paraguay currently has 3.3 million hectares of land dedicated to this activity, which constitutes 66% of the land used for the main crops.

As far as Bolivia is concerned, soybeans are grown mainly in the Santa Cruz region. According to the USDA, it represents 3% of the country's Gross Domestic Product, and employs 45,000 workers directly. In 2016, the country harvested 3.2 million tons (0.9% of world production), in an area of 1.3 million hectares

Soybean plantations occupy more than 60 percent of Uruguay's arable land, where soybean production has been increasing in recent years. In fact, it is the country where production has grown the most in relative terms in the last decade (67.7%), reaching 2.2 million tons in 2016 and a cultivated area of 1.1 million hectares.

|

Increase of the demand

The production of soy represents a very important fraction in the agricultural GDP of the South American nations. The five countries mentioned together with the United States make up 85.6% of global production, so they are the main suppliers of the growing global demand.

This production has experienced a progressive increase since its insertion in the market, with the exception of Uruguay, whose product expansion has been more recent. In the period between 1980 and 2005, for example, the total world demand for soybean expanded by 174.3 million tons, or what is the same, 2.8 times. In this period, the growth rate of global demand accelerated, from 3% annually in the 1980s to 5.6% annually in the last decade.

In all the South American countries mentioned, the cultivation of soy has been especially encouraged, because of the benefits that it entails. Thus, in Brazil, the largest regional producer of oilseed, soybean provides an estimated income of 10,000 million dollars in exports, representing 14% of the total products marketed by the country. In Argentina, soybean cultivation went from representing 10.6% of agricultural production in 1980/81 to more than 50% in 2012/2013, generating significant economic benefits.

The outlook for growth in demand suggests a continuation of the increase in production. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that global production will exceed 500 million tons in 2050, which doubles the volume harvested in 2010 and clearly, much of that demand will have to be met from South America.

La constante expansión del cultivo en los países de Mercosur les lleva a superar el 50% de la producción mundial

La soja es el producto agrícola con mayor crecimiento comercial en el mundo. Las necesidades de China e India, grandes consumidores del fruto de esta planta oleaginosa y sus derivados, convierten a Sudamérica en un granero estratégico. Su rentabilidad ha incentivado la extensión del cultivo, especialmente en Brasil y Argentina, pero también en Paraguay, Bolivia y Uruguay. Su expansión está detrás de recientes desforestaciones en el Amazonas y en el Gran Chaco. Tras los hidrocarburos y los minerales, la soja es la otra gran materia prima de Sudamérica.

ARTÍCULO / Daniel Andrés Llonch [Versión en inglés]

La soja se ha cultivado en las civilizaciones asiáticas durante miles de años; hoy su cultivo está también ampliamente difundido en otras partes del mundo. Ha pasado a ser el grano oleaginoso más importante para el consumo humano y la alimentación animal. De grandes propiedades nutritivas, por su alto contenido proteínico, la soja se comercializa tanto en grano como en sus derivados de aceite y de harina.

De los once mayores productores de soja, cinco están en Sudamérica: Brasil, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia y Uruguay. En 2016, esos países fueron el origen del 50,6% de la producción mundial, cuyo total alcanzó los 334,8 millones de toneladas, según los datos de la FAO. El primer productor fue Estados Unidos (34,9% de la producción mundial), seguido de Brasil (28,7%) y Argentina (17,5%). En la lista siguen India y China, aunque lo significativo de este último país es su gran consumo, que en 2016 le obligó a importar 83,2 millones de toneladas. Gran parte de esas necesidades de importación son cubiertas desde Sudamérica. La producción sudamericana se centra en las naciones de Mercosur (además de Brasil y Argentina, también Paraguay y Uruguay) y Bolivia.

La fuerte demanda internacional y la elevada rentabilidad relativa de la soja en los últimos años ha alimentado la expansión del cultivo de esta planta en la región del Mercosur. El boom del precio las materias primas, del que también participó la soja, originó unos beneficios que se dirigieron a la adquisición de nuevas tierras y equipamiento, lo que permitió a los productores aumentar su escala y eficiencia.

En Argentina, Bolivia, Brasil y Paraguay la superficie sembrada con soja es la mayoritaria (constituye más del 50% de la superficie total sembrada con los cinco cultivos más importantes de cada país). Si al grupo añadimos Uruguay, donde la soja ha gozado de una expansión más tardía, tenemos que la producción de esos cinco países sudamericanos ha pasado de 99 millones de toneladas en 2006 a 169,7 millones en 2016, lo que constituye un alza del 71,2% (Brasil y Bolivia han casi doblado su producción, algo superado por Paraguay y Uruguay, país donde se ha triplicado). En la década, esta área de Sudamérica ha pasado de aportar el 44,7% de la producción mundial a sumar el 50,6%. En ese tiempo, la superficie cultivada aumentó de 40,6 millones de hectáreas a 58,4 millones.

|

Países

Como el segundo mayor productor de soja del mundo, Brasil alcanzó en 2016 una producción de 96,2 millones de toneladas (el 28,7% del total mundial), con un área de cultivo de 33,1 millones de hectáreas. Su producción ha conocido un constante aumento, de forma que en el último decenio el volumen de la cosecha se ha incrementado en un 83,5%. El salto ha sido especialmente notable en los cuatro últimos años, en los que Brasil y Argentina han experimentado la mayor tasa de incremento del cultivo, con un promedio anual de 936.000 y 878.000 hectáreas, respectivamente, de acuerdo con el Departamento de Agricultura de Estados Unidos (USDA).

Argentina es el segundo país productor del Mercosur, con 58,7 millones de toneladas (el 17,5% de la producción mundial) y una extensión cultivada de 19,5 millones de hectáreas. La soja comenzó a sembrarse en Argentina a mediados de los años 70, y en menos de 40 años ha tenido un avance inédito. Este cultivo ocupa el 63% de las áreas del país sembradas con los cinco cultivos más importantes, frente al 28% de superficie que ocupan el maíz y el trigo.

Paraguay, por su parte, tuvo en 2016 una cosecha de 9,1 millones de toneladas de soja (el 2,7% de la producción mundial). En las últimas temporadas, la producción de soja ha aumentado a medida que se destinan más tierras para su cultivo. De acuerdo con el USDA, en las últimas dos décadas, la tierra dedicada al cultivo de soja ha aumentado constantemente en un 6% anual. Actualmente hay en Paraguay 3,3 millones de hectáreas de tierra dedicadas a esta actividad, lo que constituye el 66% de la tierra utilizada para los principales cultivos.

Por lo que se refiere a Bolivia, la soja se cultiva principalmente en la región de Santa Cruz. Según el USDA, representa el 3% del Producto Interno Bruto del país, y emplea a 45,000 trabajadores directamente. En 2016, el país cosechó 3,2 millones de toneladas (el 0,9% de la producción mundial), en una extensión de 1,3 millones de hectáreas.

Las plantaciones de soja ocupan más del 60 por ciento de las tierras cultivables de Uruguay, donde la producción de soja ha ido en aumento en los últimos años. De hecho, es el país donde más ha crecido la producción en términos relativos en la última década (un 67,7%), alcanzando en 2016 los 2,2 millones de toneladas y una extensión cultivada de 1,1 millones de hectáreas.

|

Aumento de la demanda

La producción de soja representa una fracción muy importante en el PIB agrícola de las naciones sudamericanas. Los cinco países mencionados juntamente con Estados Unidos conforman el 85,6% de la producción global, de forma que son los principales proveedores de la creciente demanda mundial.

Dicha producción ha experimentado un aumento progresivo desde su inserción en el mercado, con la excepción de Uruguay, cuya expansión del producto ha sido más reciente. En el periodo entre 1980 y 2005, por ejemplo, la demanda total mundial de soja se expandió en 174,3 millones de toneladas, o lo que es lo mismo, 2,8 veces. En este período la tasa de crecimiento de la demanda global fue acelerándose, desde un 3% anual en los 80 a un 5,6% anual en la última década.

En todos los países sudamericanos mecionados el cultivo de soja ha sido especialmente incentivado, por los beneficios que supone. Así, en Brasil, el mayor productor regional del grano oleaginoso, la soja aporta unos ingresos calculados en 10.000 millones de dólares en exportaciones, representando el 14% del total de productos comercializados por el país. En Argentina, el cultivo de soja pasó de representar el 10,6% de la producción agrícola en 1980/81 a más del 50% en 2012/2013, generando importantes beneficios económicos.

Las perspectivas de crecimiento de la demanda hacen prever una continuación en el alza de la producción. La Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura estima que la producción global superará los 500 millones de toneladas en 2050, lo que duplica el volumen consechado en 2010. Gran parte de esa demanda tendrá que ser atendida desde Sudamérica.

▲Trilateral Summit of Russia, Turkey and Iran in Sochi, November 2017 [Presidency of Turkey]

ANALYSIS / Albert Vidal and Alba Redondo [Spanish version]

Turkey's response to the Syrian Civil War (SCW) has gone through several phases, instructed by changing circumstances, both domestic and foreign. From supporting Sunni rebels with questionable organizational affiliations, to being a target of the Islamic State (IS), to surviving a coup attempt in 2016, a constant theme underpinning Turkish foreign policy decisions has been the Kurdish question. Despite an initially aggressive anti-Assad stance at the onset of the Syrian war, the success and growing strength of the Kurdish opposition as a result of their role in the anti-IS coalition has significantly reordered Turkish foreign policy priorities.

Relations between Turkey and Syria have been riven with difficulties over the past century. The Euphrates River, which originates in Turkey, has been one of the main causes of confrontation, with the construction of dams by Turkey limiting water flow to Syria, causing losses in agriculture and negatively impacting the Syrian economy. This issue is not confined to the past, as the ongoing GAP project (Project of the Southeast of Anatolia) threatens to further compromise water supplies to both Iraq and Syria through the construction of 22 dams and 19 hydroelectric dams.

Besides resource issues, the previous support of Hafez al-Assad to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) in the 1980s and '90s severely strained relations between the two countries, with conflict narrowly avoided with the signing of the Adana Protocol in 1998. Another source of conflict between the two countries relates to territorial claims made by both nations over the disputed Hatay province; still claimed by Syria, but administered by Turkey, which incorporated it into its territory in 1939.

Notwithstanding the above-mentioned issues between the nations - to name but a few - Syria and Turkey enjoyed a good relationship in the decade prior to the Arab Spring. The response to the Syrian regime's reaction to the uprisings by the international community has been mixed, and Turkey was no less unsure about how to position itself; eventually opting to support the opposition. As a result, Turkey offered protection on its territories to the rebels, as well as opening its borders to Syrian refugees This decision signaled the initial stage of decline in relations between the two countries, and the situation significantly worsened after the downing of a Turkish jet on 22 June 2012 by Syrian forces. Border clashes ensued, but without direct intervention of the Turkish Armed Forces.

From a foreign policy perspective, there were two primary reasons for the reversal of Turkey's non-intervention policy. The first was an increasing string of attacks by the Islamic State (IS) in the summer of 2015 in Suruç, the Central Station in Ankara, and the Atatürk Airport in Istanbul. The second, and arguably more important one, was Turkish fears of the creation of a Kurdish proto-state in neighboring Syria and Iraq. This led to the initiation of Operation Shield of the Euphrates (also known as the Jarablus Offensive), considered one of the first instances of direct military intervention by Turkey in Syria since the SCW began, with the aim of securing an area in the North of Syria free of control of IS and the Party of the Democratic Union (PYD) factions. The Jarablus Offensive was supported by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations (nations' right to self-defense), as well as a number United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolutions (Nos. 1373, 2170, 2178) corresponding to the global responsibility of countries to fight terrorism. Despite being a success in meeting its objectives, the Jarablus Offensive ended prematurely in March 2017 , without Turkey ruling out the possibility of similar future interventions.

Domestically, military intervention and a more assertive stance by Erdogan was aimed at garnering public support from both Turkish nationalist parties − notably, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and Great Unity Party (BBP) − as well as the general public for proposed constitutional changes that would lend Erdogan greater executive powers as president. Along those lines, a distraction campaign abroad was more than welcome, given the internal unrest following the coup attempt in July 2016.

Despite Turkey's growing assertiveness in neighboring Syria, Turkish military intervention does not necessarily signal strength. On the contrary, Erdogan's effective invasion of northern Syria occurred only after a number of events transpired in neighboring Syria and Iraq that threatened to undermine Turkish objectives both at home and abroad. Thus, the United States' limited intervention, and the failure of rebel forces to successfully uproot the Assad regime, meant the perpetuation of the terrorist threat but, more importantly, the continued strengthening of the Kurdish factions that have, throughout, constituted one of the most effective fighting force against IS. In effect, the success of the Kurds in the anti-IS coalition had gained it global recognition akin to that earned by most nation states; recognition that came with funding and the provision of arms. An armed Kurdish constituency, increasingly gaining legitimacy for its anti-IS efforts, is arguably the primary reason for both Turkish military intervention today, but also, a seemingly shifting stance vis-à-vis the question of Assad's position in the aftermath of the SCW.

|

▲Erdogan visits the command center for Operation Olive Branch, January 2018 [Presidency of Turkey] |

Shifting Sand: Turkey's Changing Stance vis-à-vis Assad

While Turkey aggressively supported the removal of Assad at the outset of the SCW, this idea has increasingly come to take a back seat to more important foreign policy issues regarding Turkey and its neighboring states, Syria and Iraq. In fact, recent statements by Turkish officials openly acknowledge the longevity and resilience of the government of Assad, a move that strategically leaves the door open to future reconciliation between the two parties, and reinforces a by now widely supported view that Assad is likely to be part and parcel of any future Syria deal. Thus, on 20th January 2017, Deputy Prime Minister of Turkey, Mehmet Şimşek said: "We cannot keep saying that Assad should leave. A deal without Assad is not realistic."

This relaxation of rhetoric towards Assad coincides with a Turkish pivot towards Assad's allies in the conflict (Iran and Russia) in its attempts to achieve a resolution of the conflict, yet the official Turkish position regarding Assad lacks consistency, and appears to be more dependent on prevailing circumstances. Recently, a war of words initiated by Erdogan with the Syrian president played out in the media, in which the former accused Assad of being a terrorist. Syrian foreign minister Walid Muallem, for his part, responded by accusing Erdogan of being responsible for the bloodshed of the Syrian people.

On January 2, 2018, Syrian shells were fired into Turkish territory by forces loyal to Assad. The launch provoked an immediate response from Turkey. On January 18, Mevlüt Çavusoglu, the Turkish foreign minister, announced that his country intends to carry out an air intervention in the Syrian regions of Afrin and Manbij. A few days later, Operation Olive Branch was launched under the pretext of creating a "security zone" in Afrin (in Syria’s Aleppo province) yet has been almost entirely focused on uprooting what Erdogan claims are Kurdish "terrorists", may of which belong to US-backed Kurdish factions that have played a crucial role in the anti-IS coalition. The operation was allegedly initiated in response to US plans of creating a 30.000 Syrian Kurds border force. As Erdogan commented in a recent speech: "A country we call an ally is insisting on forming a terror army on our borders. What can that terror army target but Turkey? Our mission is to strangle it before it's even born." This has significantly strained relations between the two countries, and triggered an official response from NATO in an attempt to avoid full frontal confrontation between the NATO allies in Manbij.

The US is seeking a balance between the Kurds and Turkey in the region, but it has maintained its formal support for the SDF. Nevertheless, according to analyst Nicholas Heras, the US will not help the Kurds in Afrin due to the fact that its intervention is only active in counter-IS mission areas; geographically starting from Manbij (thus Afrin not falling under US military protection).

The Impact of the Syrian Conflict on Turkey's International Relations

The Syrian conflict has strongly impacted on Turkish relations with a host of international actors, of which the most central to both Turkey and the conflict are Russia, the US, the European Union and Iran.

The demolition of a Russian SU-24 aircraft in 2015 caused a deterioration of relations between Russia and Turkey. However, thanks to the Turkish president’s apologies to Putin in June 2016, relations were normalized and a new era of cooperation between both countries has seemingly begun. This cooperation reached a high point in September of the same year when Turkey bought an S-400 defense missile system from Russia, despite warnings from its NATO allies. Further, the Russian company ROSATOM has planned the construction of a nuclear plant in Turkey worth $20 million. Thus, it can be said that cooperation between the two nations has been strengthened in the military and economic spheres.

Despite an improvement in relations however, there remain to be significant differences between both countries, particularly regarding foreign policy perspectives. On the one hand, Russia sees the Kurds as important allies in the fight against IS; consequently perceiving them to be essential to participants in post-conflict resolution (PCR) meetings. On the other, Turkey's priority is the removal of Assad and the prevention of Kurdish federalism, which translates into its rejection of including the Kurds in PCR talks. Notwithstanding, relations appear to be quite strong at the moment, and this may be due to the fact that the hostility (in the case of Turkey, growing) of both countries towards their Western counterparts trumps their disagreements regarding the Syrian conflict.

The situation regarding Turkish relations with the US is more ambiguous. By virtue of belonging to NATO, both countries share important working ties. However, even a cursory glance at recent developments suggests that these relations have been deteriorating, despite the NATO connection. The main problem between Washington and Ankara has been the Kurdish question, since the US supports the Popular Protection Units (YPG) militias in the SCW, yet the YPG are considered a designated terrorist outfit in Turkey. How the relationship will evolve is yet to be seen, and essentially revolves around both parties reaching an agreement regarding the Kurdish question. Currently, the near showdown in northern Syria is proving to be a stalemate, with Turkey clearly signaling its unwillingness to back down on the Kurdish issue, and the US risking serious face loss should it succumb to Turkey's demands. Support to the Kurds has typically been predicated on their role in the anti-IS campaign yet, with the campaign dying down, the US finds itself in a bind as it attempts to justify its continued presence in Syria. This presence is crucial to maintaining a footprint in the region and, more importantly, preventing the complete political domination of the political scene by Russia and Iran.

Beyond the Middle East scene, the US’s refusal to extradite Fetullah Gülen, a staunch enemy that, according to Ankara, was one of the instigators of the failed coup of 2016, has further strained relations. According to a survey by the Pew Research Center, only 10% of Turks trust President Donald Trump. In turn, Turkey recently stated that its agreements with the US are losing their validity. Erdogan has stressed that the dissolution of ties between both countries will seriously affect the legal and economic sphere. Furthermore, the Turk Zarrab has been found guilty in a New York trial for helping Iran evade sanctions through enabling a money-laundering scheme that filtered through US banks. This has been a big issue for Turkey, because one of the accused had ties with Erdogan's AKP party. However, Erdogan has cast the trial as a continuation of the coup attempt, and has organized a media campaign to spread the idea that Zarrab was one of the authors of the conspiracy against Turkey.

With regards the EU, relations have also soured, despite Turkey and the EU enjoying strong economic ties. As a result of Erdogan's "purge", the rapidly deteriorating situation of freedoms in Turkey have strained relations with Europe. In November 2016, the European Parliament voted to suspend EU accession negotiations with Turkey, due to human rights issues and the state of the rule of law in Turkey. By increasingly adopting the practices of an autocratic regime, Turkey's access to the EU will be essentially impossible. In a recent encounter between the Turkish and French presidents, French president Emmanuel Macron emphasized continuing EU-Turkey ties, yet suggested that there was no realistic chance of Turkey joining the EU in the near future.

Since 2017, following Erdogan’s victory in the constitutional referendum in favor of changing over from a parliamentary to a presidential system, access negotiations to the EU have effectively ceased. In addition, various European organs that deal with human rights issues have placed Turkey on "black" lists, based on their assessment that the state of democracy in Turkey is in serious jeopardy thanks to the AKP.

Another issue in relation to the Syrian conflict between the EU and Turkey relates to the refugee issue. In 2016, the EU and Turkey agreed to transfer 6 billion euros to support the Turkish reception of hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees. Although this seemed like the beginning of fruitful cooperation, tensions have continued to increase due to Turkey's limited capacity to host refugees. The humanitarian crisis in Syria is unsustainable: more than 5 million refugees have left the country and only a small segment has been granted sufficient resources to restart their lives. This problem continues to grow day by day, and more than 6 million Syrians have been displaced within its borders. Turkey welcomes more than 3 million Syrian refugees and consequently, it influences on Ankara, whose policies and position have been determined to a large extent by this crisis. On January 23, President Erdogan claimed that Turkey’s military operations in Syria will end when all the Syrian refugees in Turkey can return safely to their country. Humanitarian aid work has been underway for civilians in Afrin, where the offensive against Kurdish YPG militia fighters has been launched.

With regards the relationship between Iraq and Turkey, in November 2016, when Iraqi forces entered Mosul against the IS, Ankara announced that it would send the army to the Iraqi border, in order to prepare for important developments in the region. Turkey's defense minister added that he would not hesitate to act if Turkey's red line was crossed. He received a response from Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar Al-Abadi, who warned Turkey not to invade Iraq. Despite this, in April 2017, Erdogan suggested that in future stages, Operation Euphrates Shield would extend to Iraqi territory stating, "a future operation will not only have a Syrian dimension, but also an Iraqi dimension. Al Afar, Mosul and Sinjar are in Iraq."