Breadcrumb

Blogs

Entries with Categorías Global Affairs Asia .

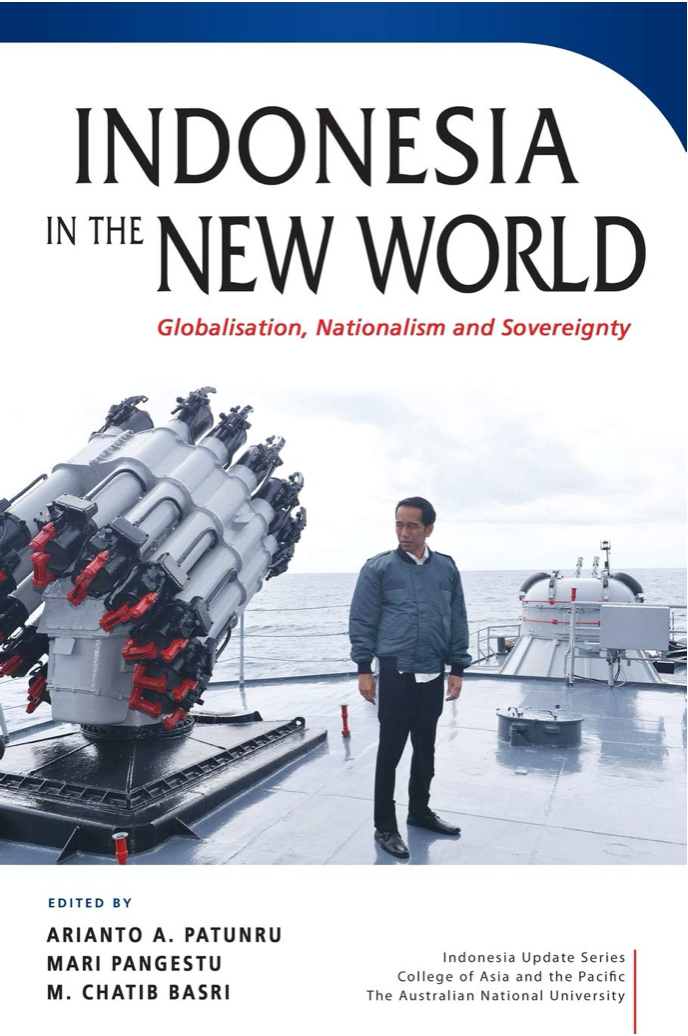

[A. Patanru, M. Pangestu, M.C. Basri (eds), Indonesia in the New World: Globalisation, Nationalism and Sovereignty. ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute. Singapore, 2018. 358 p.]

RESEÑA / Irati Zozaya

El libro se compone de quince artículos, escritos por diferentes expertos, que tratan sobre cómo Indonesia ha abordado la globalización y qué efecto ha tenido esta en el país. Los textos han sido coordinados por Arianto A. Patunru, Mari Pangestu y M. Chatib Basri, académicos indonesios con experiencia también en la gestión pública al haber sido ministros en distintos gobiernos. Los artículos combinan los enfoques generales con aspectos específicos, tales como las consecuencias de la apertura al comercio y las inversiones internacionales en la industria minera o las medidas de nacionalización de alimentos.

El libro se compone de quince artículos, escritos por diferentes expertos, que tratan sobre cómo Indonesia ha abordado la globalización y qué efecto ha tenido esta en el país. Los textos han sido coordinados por Arianto A. Patunru, Mari Pangestu y M. Chatib Basri, académicos indonesios con experiencia también en la gestión pública al haber sido ministros en distintos gobiernos. Los artículos combinan los enfoques generales con aspectos específicos, tales como las consecuencias de la apertura al comercio y las inversiones internacionales en la industria minera o las medidas de nacionalización de alimentos.

Para explicar la situación actual de Indonesia el libro en ocasiones recapitula periodos de su historia. Precisamente, uno de los conceptos que aflora con frecuencia en el libro es el del nacionalismo: podría decirse, según los autores, que es lo que más ha marcado el modo de relación de Indonesia con el mundo, más allá de quién ha dirigido en cada momento este país que hoy cuenta con 260 millones de habitantes.

La primera parte del libro hace referencia de forma más general a la experiencia de Indonesia con la globalización, el nacionalismo y la soberanía. Comienzan mostrando la época colonial y cómo, por imposición de Holanda y Gran Bretaña de una apertura al mundo, empieza a surgir un fuerte sentimiento nacionalista. Tras la ocupación por parte de Japón durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial se implanta una autarquía total, llevando así a los ciudadanos a un problema que sigue muy presente en la actualidad de Indonesia: la práctica del contrabando. En 1945 el país logró la esperada independencia bajo la presidencia de Sukarno, quien cerró Indonesia al resto del mundo para centrarse en reafirmar la identidad nacional y desarrollar sus capacidades. Esto llevó al deterioro de la economía y a la consiguiente hiperinflación, que dio pie a una nueva época: el Nuevo Orden.

En 1967, con la llegada de Suharto a la presidencia, comenzó una cautelosa apertura al comercio exterior y a los flujos de inversión. Sin embargo, Suharto reprimió la actividad política y durante su mandato los militares obtuvieron mucha influencia y el gobierno retuvo el control sobre la economía. Además, el final de su presidencia coincidió con la crisis financiera asiática (1997-1998), la cual condujo a la caída del crecimiento económico del país y a un frenazo de la reducción de la pobreza, y en consecuencia al crecimiento de la desigualdad. La crisis financiera socavó la confianza en el presidente y culminó en el colapso del Nuevo Orden.

El siguiente periodo abordado es el Reformasi, una época que marcó el comienzo de un clima político más abierto y democrático. Los siguientes dos presidentes, Abdurrahman Wahid (1999-2001) y Megawati Soekarnoputri (2001-2004), se preocuparon más por la recuperación económica y la consolidación democrática y perduró un sistema proteccionista en cuanto a la economía. El libro no se centra mucho en el siguiente presidente, Yudhoyono (2004-2014), remarcando únicamente que fue un internacionalista que mantuvo una postura más cautelosa y ambivalente en cuestiones económicas.

Por último, en las elecciones de 2014 llegó al poder Joko Widodo, quien mantiene el cargo de presidente en la actualidad. Con él, Indonesia ha vuelto a la senda del crecimiento económico y se ha estabilizado como una democracia de razonable éxito. Dado que el presidente, conocido comúnmente como Jokowi, ha tomado nuevas medidas para remarcar la soberanía política y promover la autarquía económica y el renacimiento cultural nacional, a su mandato se le ha caracterizado de ‘nuevo nacionalismo’. En su discurso político, Jokowi pone a Indonesia como objetivo de conspiraciones extranjeras y llama a estar en guardia frente a esas amenazas. De todas maneras, el país mantiene una postura ambivalente hacia la apertura y cooperación internacional ya que, por mucho que en las últimas décadas hayan vuelto a incrementar las restricciones comerciales, Jokowi enfatiza el compromiso global y ha reactivado las negociaciones regionales.

Todo esto ha llevado al descontento de la población con la globalización, de forma que hasta el 40% de los ciudadanos piensan que esta amenaza la unidad nacional. Uno de los efectos más negativos y de mayor importancia en Indonesia es el de los trabajadores que se han visto forzados a emigrar y a trabajar en el extranjero en muy malas condiciones. No obstante, las últimas partes del libro muestran también las consecuencias positivas que ha tenido la globalización en Indonesia, manifestándose en una mayor productividad, el incremento de los salarios o el crecimiento económico, entre otros. Por ello los autores hacen hincapié en la importancia de construir una narrativa que pueda generar apoyo público y político para la apertura del país y contrarreste el creciente sentimiento de antiglobalización.

Como ocurre en un libro que es la suma de artículos de diferentes autores, su lectura puede resultar algo pesada por una cierta reiteración de contenidos. No obstante, la variedad de firmas supone también una pluralidad de enfoques que sin duda supone una riqueza de perspectivas para el lector.

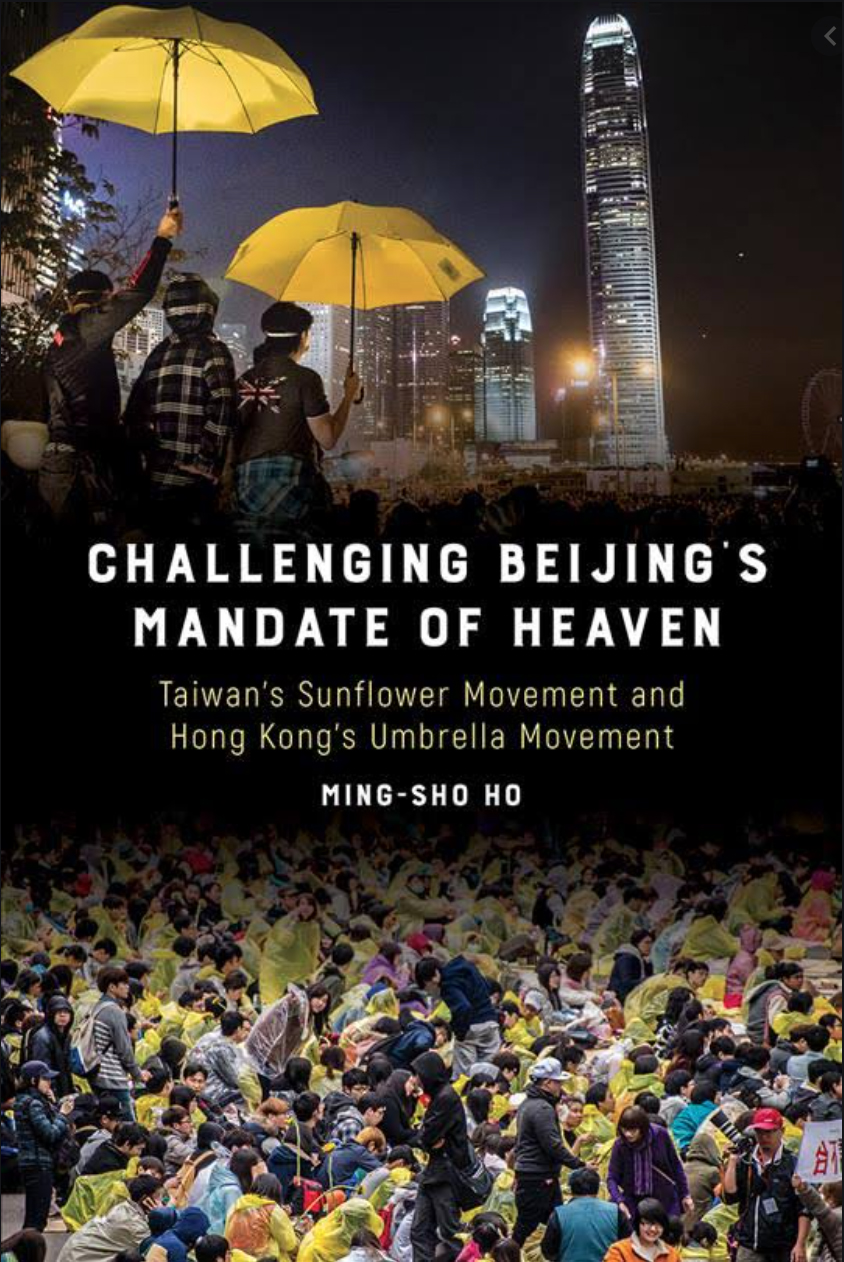

[Ming-Sho Ho, Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven. Taiwan's Sunflower and Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement. Temple University Press. Philadelphia, 2019. 230 p.]

RESEÑA / Claudia López

El Movimiento Girasol de Taiwán y el Movimiento de los Paraguas de Hong Kong alcanzaron una gran notoriedad internacional a lo largo de 2014, cuando retaron el ‘mandato del Cielo’ del régimen chino, por usar la imagen que da título al libro. Este analiza los orígenes, los procesos y también los resultados de ambas protestas, en un momento de consolidación del ascenso de la República Popular China. Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven ofrece una visión general y a la vez detallada sobre dónde, por qué y cómo estos movimientos se gestaron y alcanzaron relevancia.

El Movimiento Girasol de Taiwán y el Movimiento de los Paraguas de Hong Kong alcanzaron una gran notoriedad internacional a lo largo de 2014, cuando retaron el ‘mandato del Cielo’ del régimen chino, por usar la imagen que da título al libro. Este analiza los orígenes, los procesos y también los resultados de ambas protestas, en un momento de consolidación del ascenso de la República Popular China. Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven ofrece una visión general y a la vez detallada sobre dónde, por qué y cómo estos movimientos se gestaron y alcanzaron relevancia.

El Movimiento Girasol de Taiwán se desarrolló en marzo y abril de 2014, cuando manifestaciones ciudadanas protestaron contra la aprobación de un tratado de libre comercio con China. Entre septiembre y diciembre de ese mismo año, el Movimiento de los Paraguas protagonizó en Hong Kong 79 días de protestas exigiendo el sufragio universal para elegir a la máxima autoridad este enclave de especial estatus dentro de China. Estas protestas llamaron la atención internacionalmente por su organización, pacífica y civilizada.

Ming-Sho Ho comienza describiendo el trasfondo histórico de Taiwán y Hong Kong desde sus orígenes chinos. Luego analiza la situación de ambos territorios en lo que va del presente siglo, cuando Taiwán y Hong Kong han comenzado a encontrar mayor presión por parte de China. Además, repasa las similares circunstancias económicas que produjeron las dos oleadas de revueltas juveniles. En la segunda parte del libro, se analizan los dos movimientos: las contribuciones voluntarias, el proceso de toma de decisiones y su improvisación, el cambio de poder interno, las influencias políticas y los desafíos de la iniciativa. La obra incluye apéndices con la lista de personas de Taiwán y Hong Kong entrevistadas y la metodología utilizada para el análisis de las protestas.

Ming-Sho Ho nació en 1973 en Taiwán y ha sido un observador directo de los movimientos sociales de la isla; durante su época de estudiante de doctorado en Hong Kong también siguió de cerca el debate político en la excolonia británica. En la actualidad está investigando iniciativas para promover la energía renovable en las naciones de Asia Oriental.

El hecho de ser de Taiwán le dio acceso al Movimiento Girasol y le permitió entablar una estrecha relación con varios de sus principales activistas. Pudo presenciar algunas de las reuniones internas de los estudiantes y llevar a cabo entrevistas en profundidad con estudiantes, líderes, políticos, activistas de ONG, periodistas y profesores universitarios. Eso le proporcionó una variedad de fuentes para llevar a cabo su investigación.

Si bien son dos territorios con características distintas –Hong Kong se encuentra bajo soberanía de la República Popular China, pero goza de autonomía administrativa; Taiwán sigue siendo independiente, pero su condición de estado se ve desafiada–, ambos suponen un reto estratégico para Pekín en su consolidación como superpotencia.

La simpatía del autor hacia estos dos movimientos es obvia en todo el libro, así como su admiración por el riesgo asumido por estos grupos de estudiantes, especialmente en Hong Kong, donde muchos de ellos fueron declarados culpables de ‘molestia pública’ y de ‘alteración del orden público’ y, en numerosos casos, acabaron condenados a más de un año de prisión.

Los dos movimientos tuvieron un comienzo y un desarrollo parecidos, pero cada cual terminó de manera muy distinta. En Taiwán, gracias a la iniciativa, el tratado de libre comercio con China no prosperó y fue retirado, y los manifestantes pudieron convocar un acto de despedida para celebrar esa victoria. En Hong Kong, la represión policial logró ir ahogando la protesta y se produjo una última redada masiva que supuso un final decepcionante para los manifestantes. No obstante, es posible que sin la experiencia de aquellas movilizaciones no hubiera sido posible la nueva reacción estudiantil que a lo largo de 2019 y comienzos de 2020 ha puesto contra las cuerdas en Hong Kong a las máximas autoridades chinas.

![Logo of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence organization. It depicts Pakistan's national animal, Markhor, eating a snake [Wikipedia] Logo of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence organization. It depicts Pakistan's national animal, Markhor, eating a snake [Wikipedia]](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-isi-blog.jpg)

▲ Logo of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence organization. It depicts Pakistan's national animal, Markhor, eating a snake [Wikipedia]

ESSAY / Manuel Lamela

Jihadism continues to be one of the main threats Pakistan faces. Its impact on Pakistani society at the political, economic and social levels is evident, it continues to be the source of greatest uncertainty, which acts as a barrier to any company that is interested in investing in the Asian country. Although the situation concerning terrorist attacks on national soil has improved, jihadism is an endemic problem in the region and medium-term prospects are not positive. The atmosphere of extreme volatility and insistence that is breathed does not help in generating confidence. If we add to this the general idea that Pakistan's institutions are not very strong due to their close links with certain radical groups, the result is a not very optimistic scenario. In this essay, we will deal with the current situation of jihadism in Pakistan, offering a multidisciplinary approach that helps to situate itself in the complicated reality that the country is experiencing.

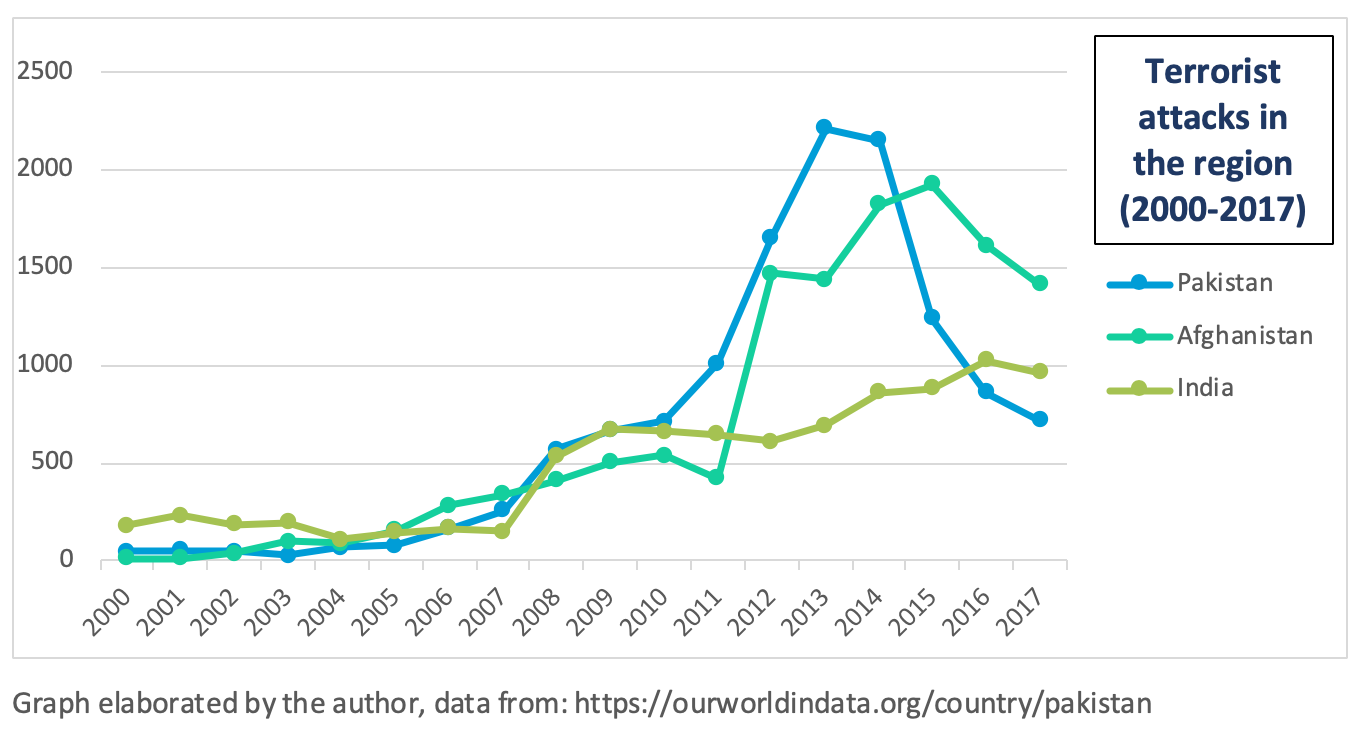

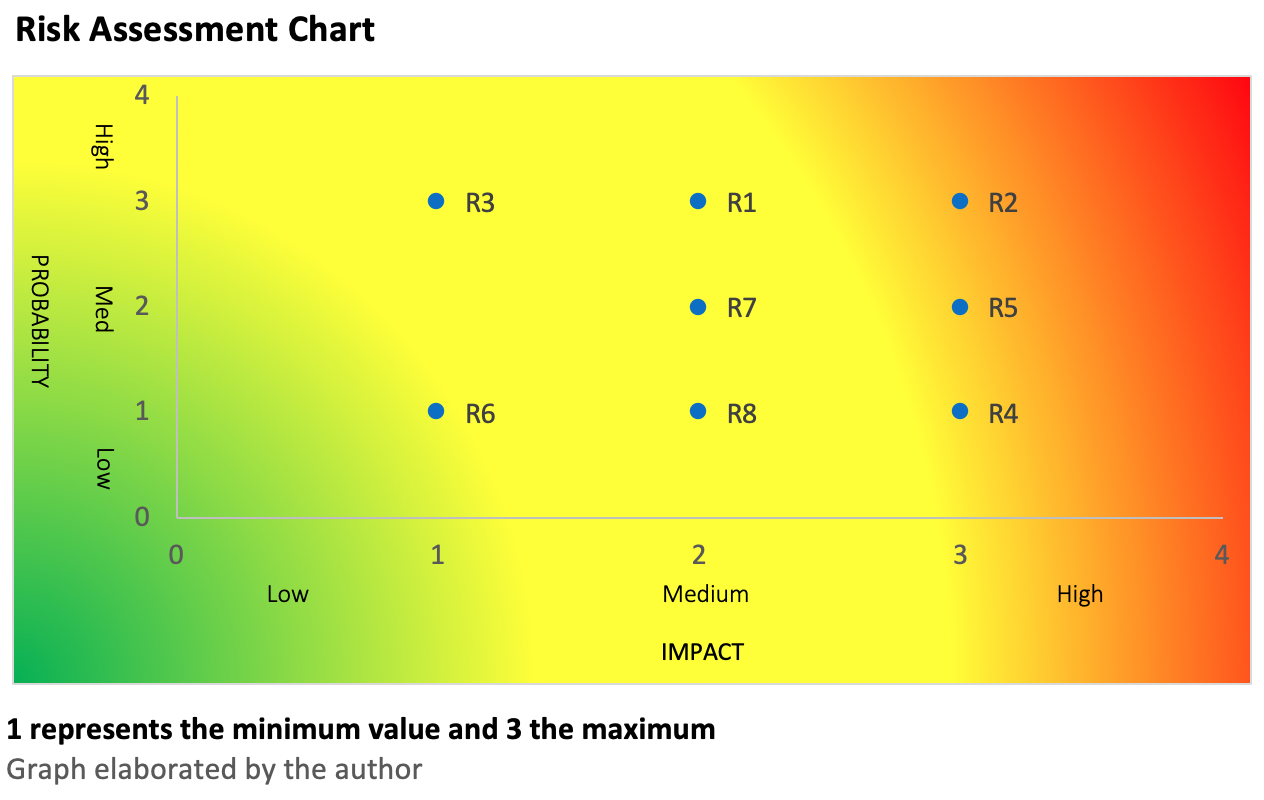

1. Jihadism in the region, a risk assessment

Through this graph, we will analyze the probability and impact of various risk factors concerning jihadist activity in the region. All factors refer to hypothetical situations that may develop in the short or medium term. The increase in jihadist activity in the region will depend on how many of these predictions are fulfilled.

Risk Factors:

R1: US-Taliban treaty fails, creating more instability in the region. If the United States is not able to make a proper exit from Afghanistan, we may find ourselves in a similar situation to that experienced during the 1990s. Such scenario will once again plunge the region into a fierce civil war between government forces and Taliban groups. The proposed scenario becomes increasingly plausible if we look at the recent American actions regarding foreign policy.

R2: Pakistan two-head strategy facing terrorism collapse. Pakistan’s strategy in dealing with jihadism is extremely risky, it’s collapse would lead to a schism in the way the Asian state deals with its most immediate challenges. The chances of this strategy failing in the medium term are considerably high due to its structure, which makes it unsustainable over the time.

R3: Violations of the LoC by the two sides in the conflict. Given the frequency with which these events occur, their impact is residual, but it must be taken into account that it in an environment of high tension and other factors, continuous violations of the LoC may be the spark that leads to an increase in terrorist attacks in the region.

R4: Agreement between the afghan Taliban and the government. Despite the recent agreement between Ashraf Ghani and Abdullah Albduallah, it seems unlikely that he will be able to reach a lasting settlement with the Taliban, given the latter's pretensions. If it is true that if it happens, the agreement will have a great impact that will even transcend Afghan borders.

R5: Afghan Taliban make a coup d’état to the afghan government. In relation to the previous point, despite the pact between the government and the opposition, it seems likely that instability will continue to exist in the country, so a coup attempt by the Taliban seems more likely than a peaceful solution in the medium or long term

R6: U.S. Democrat party wins the 2020 elections. Broadly speaking, both Republican and Democratic parties are betting on focusing their efforts on containing the growth of their great rival, China.

R7: U.S. withdraw its troops from Afghanistan regarding the result of the peace process. This is closely related to the previous point as it responds to a basic geopolitical issue.

R8: New agreement between India and Pakistan regarding the LoC. If produced, this would bring both states closer together and help reduce jihadist attacks in the Kashmir region. However, if we look at recent events, such a possibility seems distant at present.

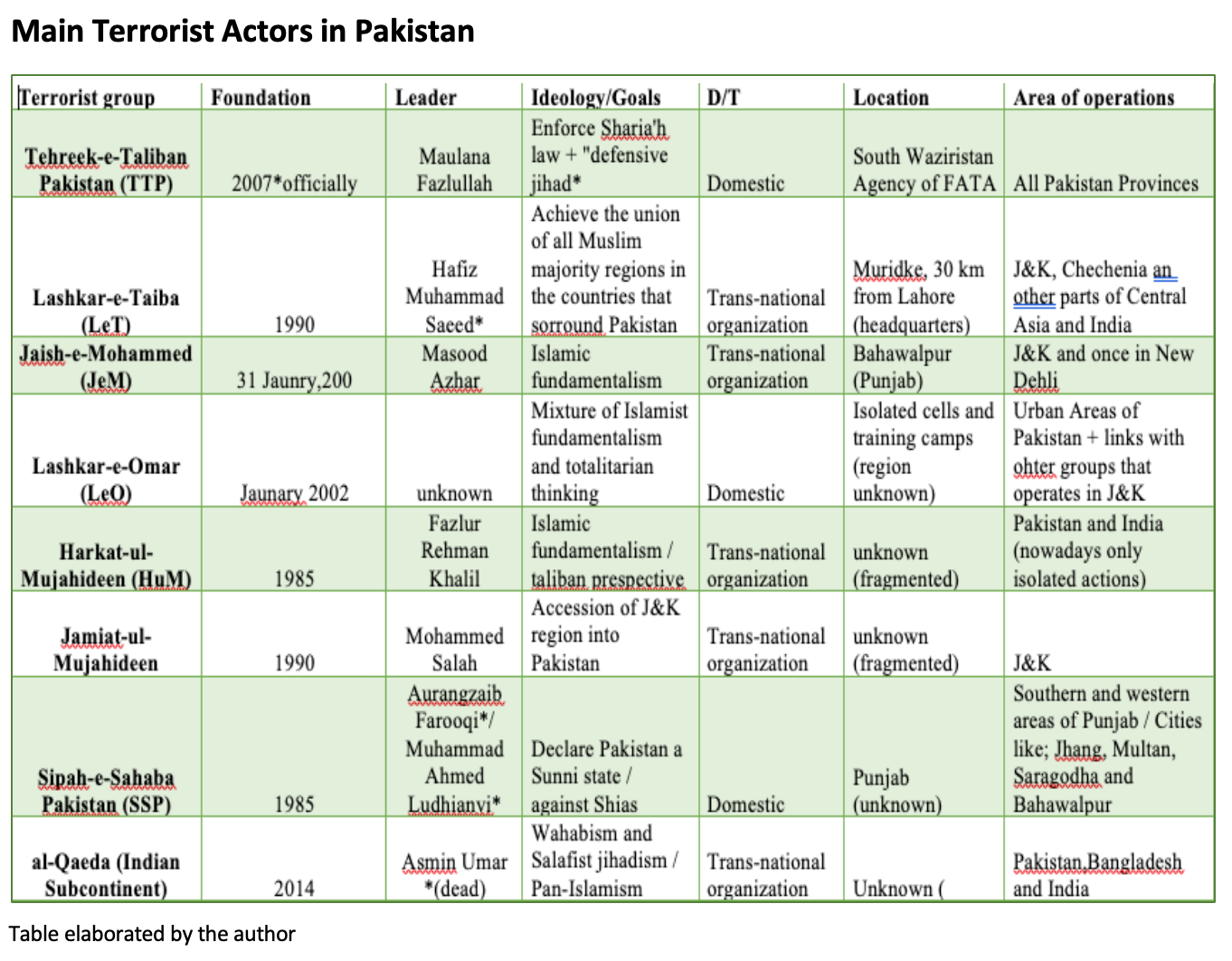

2. The ties between the ISI and the Taliban and other radical groups

Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) has been accused on many occasions of being closely linked to various radical groups; for example, they have recently been involved with the radicalization of the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh[1]. Although Islamabad continues strongly denying such accusations, reality shows us that cooperation between the ISI and various terrorist organizations has been fundamental to their proliferation and settlement both on national territory and in the neighboring states of India and Afghanistan. The West has not been able to fully understand the nature of this relationship and its link to terrorism. The various complaints to the ISI have been loaded with different arguments of different kinds, lacking in unity and coherence. Unlike popular opinion, this analysis will point to the confused and undefined Pakistani nationalism as the main cause of this close relationship.

The Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence, together with the Intelligence Bureau and the Military Intelligence, constitute the intelligence services of the Pakistani State, the most important of which is the ISI. ISI can be described as the intellectual core and center of gravity of the army. Its broad functions are the protection of Pakistan's national security and the promotion and defense of Pakistan's interests abroad. Despite the image created around the ISI, in general terms its activities and functions are based on the same "values" as other intelligence agencies such as the MI6, the CIA, etc. They all operate under the common ideal of protecting national interests, the essential foundation of intelligence centers without which they are worthless. We must rationalize their actions on the ground, move away from inquisitive accusations and try to observe what are the ideals that move the group, their connection with the government of Islamabad and the Pakistani society in general.

2.1. The Afghan Taliban

To understand the idiosyncrasy of the ISI we must go back to the war in Afghanistan[2], it is from this moment that the center begins to build an image of itself, independent of the rest of the armed forces. From the ISI we can see the victory of the Mujahideen on Afghan territory as their own, a great achievement that shapes their thinking and vision. But this understanding does not emerge in isolation and independently, as most Pakistani society views the Afghan Taliban as legitimate warriors and defenders of an honorable cause[3]. The Mujahideen victory over the USSR was a real turning point in Pakistani history, the foundation of modern Pakistani nationalism begins from this point. The year 1989 gave rise to a social catharsis from which the ISI was not excluded.

Along with this ideological component, it is also important to highlight the strategic aspect; we are dealing with a question of nationalism, of defending patriotic interests. Since the emergence of the Taliban, Pakistan has not hesitated to support them for major strategic reasons, as there has always been a fear that an unstable Afghanistan would end up being controlled directly or indirectly by India, an encircle strategy[4]. Faced with this dangerous scenario, the Taliban are Islamabad's only asset on the ground. It is for this reason, and not only for religious commitment, that this bond is produced, although over time it is strengthened and expanded. Therefore, at first, it is Pakistani nationalism and its foreign interests that are the cause of this situation, it seeks to influence neighboring Afghanistan to make the situation as beneficial as possible for Pakistan. Later on, when we discuss the situation of the Taliban on the national territory, we will address the issue of Pakistani nationalism and how its weak construction causes great problems for the state itself. But on Afghan territory, from what has been explained above, we can conclude that this relationship will continue shortly, it does not seem likely that this will change unless there are great changes of impossible prediction. The ISI will continue to have a significant influence on these groups and will continue its covert operations to promote and defend the Taliban, although it should be noted that the peace treaty between the Taliban and the US[5] is an important factor to take into account, this issue will be developed once the situation of the Taliban at the internal level is explained.

2.2. The Pakistani Taliban (Al-Qaeda[6] and the TTP)

The Taliban groups operating in Pakistan are an extension of those operating in neighboring Afghanistan. They belong to the same terrorist network and seek similar objectives, differentiated only by the place of action. Despite this obvious similarity, from Islamabad and increasingly from the whole of Pakistani society, the two groups are observed in a completely different way. On the one hand, as we said earlier, for most Pakistanis, the Afghan Taliban are fighting a legitimate and just war, that of liberating the region from foreign rule. However, groups operating in Pakistan are considered enemies of the state and the people. Although there was some support among the popular classes, especially in the Pashtun regions, this support has gradually been lost due to the multitude of atrocities against the civilian population that have recently been committed. The attack carried out by the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP)[7] in the Army Public School in Peshawar in the year 2014 generated a great stir in society, turning it against these radical groups. This duality marks Pakistan's strategy in dealing with terrorism both globally and internationally. While acting as an accomplice and protector of this groups in Afghanistan, he pursues his counterparts on their territory. We have to say that the operations carried out by the armed forces have been effective, especially the Zarb-e-Azb operation carried out in 2014 in North Waziristan, where the ISI played a fundamental role in identifying and classifying the different objectives. The position of the TTP in the region has been decimated, leaving it quite weakened. As can be seen in this scenario, there is no support at the institutional level from the ISI[8], as they are involved in the fight against these radical organizations. However, on an individual level if these informal links appear. This informal network is favored by the tribal character of Pakistani society, it can appear in different forms but often draw on ties of Kinship, friendship or social obligation[9]. Due to the nature of this type of relationship, it is impossible to know to what extent the ISI's activity is conditioned and how many of its members are linked to Taliban groups. However, we would like to point out that these unions are informal and individual and not institutional, which provides a certain degree of security and control, at least for the time being, the situation may vary greatly due to the lack of transparency.

2.3. ISI and the radical groups that operate in Kashmir

Another part of the board is made up of the radical groups that focus their terrorist attention on the conflict with India over control of Kashmir, the most important of which are: Lashkar-e-Taiba (Let) and Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM). Both groups have committed real atrocities over the past decades, the most notorious being the one committed by LeT in the Indian city of Mumbai in 2008. There are numerous testimonies, in particular, that of the American citizen David Haedy, which point to the cooperation of the ISI in carrying out the aforementioned attack.[10]

Recently, Hafiz Saeed, founder of Let and intellectual planner of the bloody attack, was arrested. The news generated some turmoil both locally and internationally and opened the debate as to whether Pakistan had finally decided to act against the radical groups operating in Kashmir. We are once again faced with a complex situation, although the arrest shows a certain amount of willpower, it is no more than a way of making up for the situation and relaxing international pressure. The above coincides with the FATF's[11] assessment of Pakistan's status within the institution, which is of great importance for the short-term future of the country's economy. Beyond rhetoric, there is no convincing evidence that suggests that Pakistan has made a move against those groups. The link and support provided by the ISI in this situation are again closely linked to strategic and ideological issues. Since its foundation, Pakistani foreign policy has revolved around India[12], as we saw on the Afghan stage. Pakistani nationalism is based on the maxim that India and the Hindus are the greatest threat to the future of the state. Given the significance of the conflict for Pakistani society, there has been no hesitation in using radical groups to gain advantages on the ground. From Pakistan perspective, it is considered that this group of terrorists are an essential asset when it comes to putting pressure on India and avoiding the complete loss of the territory, they are used as a negotiating tool and a brake on Indian interests in the region.

As we can see, the core between the ISI and certain terrorist groups is based on deep-seated nationalism, which has led both members of the ISI and society, in general, to identify with the ideas of certain radical groups. They have benefited from the situation by bringing together a huge amount of power, becoming a threat to the state itself. The latter has compromised the government of Pakistan, sometimes leaving it with little room for maneuver. The immense infrastructure and capacity of influence that Let has thanks to its charitable arm Jamaat-ud-Dawa, formed with re-localized terrorists, is a clear example of the latter. A revolt led by this group could put Islamabad in a serious predicament, so the actions taken both in Kashmir and internally to try to avoid the situation should be measured very well. The existing cooperation between the ISI and these radical groups is compromised by the development of the conflict in Kashmir, which may increase or decrease depending on the situation. What is certain, because of the above, is that it will not go unnoticed and will continue to play a key role in the future. These relationships, this two-way game could drag Pakistan soon into an internal conflict, which could compromise its very existence as a nation.

[1] Ahmed, Zobaer. "Is Pakistani Intelligence Radicalizing Rohingya Refugees? | DW | 13.02.2020". DW.COM, 2020.

[2] Idrees, Muhammad. Instability In Afghanistan: Implications For Pakistan. PDF, 2019.

[3] Lieven, Anatol. Pakistan a Hard Country. 1st ed. London: Penguin, 2012.

[4] United States Institute for Peace. The India-Pakistan Rivalry In Afghanistan, 2020.

[5] Maizland, Lindsay. "U.S.-Taliban Peace Deal: What To Know". Council On Foreign Relations, 2020.

[6] Blanchard, Christopher M. Al Qaeda: Statements And Evolving Ideology. PDF, 2007.

[7] Mapping Militant Organizations. “Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan.” Stanford University. Last modified July 2018.

[8] Gabbay, Shaul M. Networks, Social Capital, And Social Liability: The Cae Of Pakistan ISI, The Taliban And The War Against Terrorism.PDF, 2014. http://www.scirp.org/journal/sn.

[9] Lieven, Anatol. Pakistan a Hard Country. 1st ed. London: Penguin, 2012.

[10] Lieven, Anatol. Pakistan a Hard Country. 1st ed. London: Penguin, 2012.

[11] "Pakistan May Remain On FATF Grey List Beyond Feb 2020: Report". The Economic Times, 2019.

[12] "India And Pakistan: Forever Rivals?". Aljazeera.Com, 2017.

![Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, also called Kartarpur Sahib, is a Sikh holy place in Kartarpur, in the Pakistani Punjab [Wikimedia Commons] Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, also called Kartarpur Sahib, is a Sikh holy place in Kartarpur, in the Pakistani Punjab [Wikimedia Commons]](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-punjab-blog.jpg)

▲ Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, also called Kartarpur Sahib, is a Sikh holy place in Kartarpur, in the Pakistani Punjab [Wikimedia Commons]

ESSAY / Pablo Viana

Punjab region has been part of India until the year 1947, when the Punjab province of British India was divided in two parts, East Punjab (India) and West Punjab (Pakistan) due to religious reasons. After the division a lot of internal violence occurred, and many people were displaced.

East and West Punjab

The partition of Punjab proved to be one of the most violent, brutal, savage debasements in the history of humankind. The undivided Punjab, of which West Punjab forms a major region today, was home to a large minority population of Punjabi Sikhs and Hindus unto 1947 apart from the Muslim majority[1]. This minority population of Punjabi Sikhs called for the creation of a new state in the 1970s, with the name of Khalistan, but it was detained by India, sending troops to stop the militants. Terrorist attacks against the Sikh majority emerged, by those who did not accept the creation of the state of Khalistan and wished to stay in India.

The Sikh population is the dominant religious ethnicity in East Punjab (58%) followed by the Hindu (39%). Sikhism and Islamism are both monotheistic religions, they do believe on the same concept of God, although it is different on each religion. Sikhism was developed during the 16th and 17th century in the context of conflict in between Hinduism and Islamism. It is important to mention Sikhism if we talk about Punjab, as its origins were in Punjab, but most important in recent times, is that the Guru Nanak Dev[2] was buried in Pakistani territory. Four kilometres from the international border the Sikh shrine was conceded to Pakistan at the time of British India’s Partition in 1947. For followers of Sikhism this new border that cut through Punjab proved especially problematic. Sikhs overwhelmingly chose India over the newly formed Pakistan as the state that would best protect their interests (there are an estimated 50,000 Sikhs living in Pakistan today, compared to the 24 million in India). However, in making this choice, Sikhs became isolated from several holy sites, creating a religious disconnection that has proved a constant spiritual and emotional dilemma for the community[3].

In order to let the Sikhist population visit the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib[4], the Kartarpur Corridor was created in November 2019. However, there is an incessant suspicion in between India and Pakistan that question Pakistan motives. Although it seems like a generous move work of the Pakistani government, there is a clear perception that Pakistan is engaged in an act of deception[5]. Thus, although this scenario might seem at first beneficial for the rapprochement of East and West Punjab, it is not at all. Pakistan is involved in a rhetorical policy which could end up worsening its relations with India.

The division of Punjab in 1947 was like the division of Pakistan and India on that same year. Territorial disputes have been an issue that defines very well India-Pakistan relations since the independence. In the case of Punjab, there has not been a territorial debate. The division was clear and has been respected ever since. Why would Pakistan and/or India be willing to unify Punjab? There is no reason. East and West Punjab represent two different nations and three religions. If we think about reunifying Pakistan and India, the conclusion is the same (although more dramatic); too many discrepancies and recent unrest to think about bringing back together the nations. However, if the Kartarpur Corridor could be placed out of bonds for the territorial disputes between Pakistan and India (e.g. Kashmir), Islamabad and New Delhi could use this situation as a model to find out which are the pressure points and trying to find a path for identifying common solutions. In order to achieve this, there should be a clear behaviour by both parts of cooperation. Sadly, in recent times both Pakistan and India have discrepancies regarding many topics and suspicious behaviours that clearly show that they won’t be interested in complicating more the situation in Punjab searching for unification. The riots of 1947 left a terrific era on the region and now that both sides are established and no major disputes have emerged (except for Sikh nationalism), the situation should and will most likely remain as it is.

The Indus Water Treaty

The Indus Waters Treaty was signed in 1960 after nine years of negotiations between India and Pakistan with the help of the World Bank, which is also a signatory. Seen as one of the most successful international treaties, it has survived frequent tensions, including conflict, and has provided a framework for irrigation and hydropower development for more than half a century. The Treaty basically provides a mechanism for exchange of information and cooperation between Pakistan and India regarding the use of their rivers. This mechanism is well known as the Permanent Indus Commission. The Treaty also sets forth distinct procedures to handle issues which may arise: “questions” are handled by the Commission; “differences” are to be resolved by a Neutral Expert; and “disputes” are to be referred to a seven-member arbitral tribunal called the “Court of Arbitration.” As a signatory to the Treaty, the World Bank’s role is limited and procedural[6].

Since 1948, India has been confident on the fact that East Punjab and the acceding states have a prior and superior claim to the rivers flowing through their territory. This leaves West Punjab in disadvantage regarding water resources, as East Punjab can access the highest sections of the rivers. Even under a unified control designed to ensure equitable distribution of water, in years of low river flow cultivators on tail distributaries always tended to accuse those on the upper reaches of taking an undue amount of the water, and after partition any temporary shortage, whatever the cause, could easily be attributed to political motives. It was therefore wise of Pakistan-indeed it became imperative-to cut the new feeder from the Ravi for this area and thus become independent of distributaries in East Punjab[7]. The Treaty acknowledges the control of the eastern rivers to India, and to the western rivers to Pakistan.

The main issue of water distribution in between East and West Punjab is then a matter of geography. Even though West Punjab covers more territory than East Punjab, and the water flow of West Punjab is almost three times the water flow of East Punjab rivers, the Indus Water Treaty gives the following advantage to India: since Pakistan rivers receive much more water flow from India, the treaty allowed India to use western rivers water for limited irrigation use and unlimited use for power generation, domestic, industrial and non-consumptive uses such as navigation, floating of property, fish culture and this is where the disputes mainly came from, as Pakistan has objected all Indian hydro-electric projects on western rivers irrespective of size and layout.

It is worth mentioning that with the World Bank mediating the Treaty in between India and Pakistan, the water access will not be curtailed, and since the ratification of the Treaty, India and Pakistan have not engaged in any water wars. Although there have been many tensions the disputes have been via legal procedures, but they haven’t caused any major cause for conflict. Today, both countries are strengthening their relationship, and the scenario is not likely to get worse, it is actually the opposite, and the Indus Water Treaty is one of the few livelihoods of the relationship. If the tensions do not cease, the World Bank should consider the possibility of amending the treaty, obviously if both Pakistan and India are willing to cooperate, although with the current environment, a renegotiation of the treaty would probably bring more complications. There is no shred of evidence that India has violated the Indus Water Treaty or that it is stealing Pakistan’s water[8], although Pakistan does blame India for breaching the treaty, as showed before. This is pointed out by Hindu politicians as an attempt by Pakistan to divert the attention of its own public from the real issues of gross mismanagement of water resources[9].

Pakistan has a more hostile attitude regarding water distribution, trying to find a way to impeach India, meanwhile India focuses on the development of hydro-electric projects. India won’t stop providing water to the West Punjab, as the treaty is still in force and is fulfilled by both parts. Pakistan should reconsider its role and its benefits received thanks to the treaty and meditate about the constant pressure towards India, as pushing over the limit could mean a more hostile activity carried out by India, which in the worst case scenario (although not likely to happen) could mean a breakdown of the treaty.

[1] The Punjab in 1920s – A Case study of Muslims, Zarina Salamat, Royal Book Company, Karachi, 1997. table 45, pp. 136.

[2] Guru Nanak Dev was the founder of Sikhism (1469-1540)

[3] Wyeth, G. (Dec 28, 2019). Opening the Gates: The Kartarpur Corridor. Australian Institute of International Affairs.

[4] Site where Guru Nanak Dev settled the Sikh community, and lived for 18 years after his death in 1539.

[5] Islamabad promoted the activity of Sikhs For Justice including the will to establish the state of Khalistan.

[6] World Bank (June 11, 2018). Fact Sheet: The Indus Waters Treaty 1960 and the Role of the World Bank.

[7] F.J. Fowler (Oct 1950) Some Problems of Water Distribution between East and West Punjab p. 583-599.

[8] S. Chandrasekharan (Dec 11, 2017) Indus Water Treaty: Review is not an Option South Asia Analysis Group.

[9] Mohan, G. (Feb 3, 2020). India rejects Pakistan media report on Indus water sharing India Today.

![Attack in Kashmir linked to groups of Pakistani origin [twitted by @ANI] Attack in Kashmir linked to groups of Pakistani origin [twitted by @ANI]](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-yihadismo-blog.jpg)

▲ Attack in Kashmir linked to groups of Pakistani origin [twitted by @ANI]

ESSAY / Isabel Calderas [Ignacio Lucas as research assistant]

There is a myriad of security concerns regarding external factors when it comes to Pakistan: India, Afghanistan, the Saudi Arabia-Iran split and the United States, to name a few. However, there are also two main concerns that come from within: jihadism and organized crime. They are interconnected but differ in many ways. The latter is frequently overlooked to focus on the former, but both have the capacity of affecting the country, internally and externally, as the effectiveness of dealing with them impacts the perception the international community has of Pakistan. While internally disrupting, these problems also have international reach, as such groups often export their activities, adversely affecting at a global scale. Therefore, international actors put so much pressure on Pakistan to control them. Historically, there has been much scepticism over the government’s ability, or even willingness to solve these risks. We will examine both problems separately, identifying the impact they have on the national and international arena, as well as the government’s approach to dealing with either and the future risks they entail.

1. JIHADISM

Pakistan’s education system has become a central part of the country’s radicalization phenomenon[1], in the materialization of madrassas. These schools, which teach a more puritanical version of Islam than had traditionally been practiced in Pakistan, have been directly linked to the rise of jihadist groups[2]. Saudi Arabia, who has always had very close relations with Pakistan, played a key role in their development, by funding the Ahl-e-Hadith and Deobandi madrassas since the 1970s. The Iranian revolution bolstered the Saudi’s imperative to control Sunnism in Pakistan, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan gave them the vehicle to do so[3]. In these schools, which teach a biased view of the world, students display low tolerance for minorities and are more likely to turn to jihadism.

Saudi and American funding of madrassas during the Soviet occupation helped the Pakistani army’s intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), become more powerful, as they channelled millions of dollars to them, a lot of which went into the madrassas which sent mujahedeen fighters to fight for their cause[4]. The Taliban’s origins can also be traced to these, as the militia was raised mainly from Afghan refugee camps in Pakistan and Saudi-funded madrassas[5].

Madrassas are especially popular in the poorer provinces of the country, where parents send their children to them for several non-religious reasons. First, because the Qur’an is written in Arabic and madrassas teach this language[6]. The dire situation of many families forces millions of Pakistanis to migrate to neighbouring, oil-rich Arabic-speaking countries, from where they send remittances home to help support their families. Secondly, the public-school system in Pakistan is weak, often failing to teach basic reading skills[7], something the madrassas do teach.

Partly in response to the international pressure[8] it has been under to fight terrorism within its territory; Pakistan has tried to reform the madrassas. The government has stated its intention to bring madrassas under the umbrella of the education ministry, financing these schools by allocating cash otherwise destined to fund anti-terrorism security operations[9]. It plans to add subjects like science to the curriculum, to lessen the focus on Islamic teachings. However, this faces several challenges, among which the resistance from the teachers and clerical authorities who run the madrassas outstands[10].

Before moving on to the prominent radical groups in Pakistan, we would like to make a brief summary on a different cause of radicalization: the unintended effect of the drone strategy adopted by the United States.

The United States has increasingly chosen to target its radical enemies in Pakistan through the use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), which can be highly effective in neutralizing objectives, but also pose a series of risks, like the killing of innocent civilians that are in the neighbouring area. This American strategy, which Pakistan has publicly criticized, has fomented anti-American sentiment among the Pakistanis, at a ratio on average of every person killed resulting in the radicalization of several more people[11]. The growing unpopularity of drone strikes has further weakened relations between both governments, but shows no signs of changing in the future, if recent attacks carried by the U.S. are any indication. Pakistan’s efforts to de-radicalize its population will continue to be undermined by the U.S. drone strikes[12].

Pakistan’s anti-terrorism strategy is linked to its geostrategic and regional interests, especially dealing with its eastern and western neighbours[13]. There are many radical groups operating within their territory, and the government’s strategy towards them shifts depending on their goal[14]. Groups like the Afghan Taliban, who target foreign invasions in their own country, and Al Qaeda, whose jihad against the West is on a global scale, have been allowed to use Pakistani territory to coordinate operations and take refuge. Their strategy is quite different for Pakistani Taliban group, Tehrik-e-Taliban (TTP) who, despite being allied with the Afghan Taliban, has a different goal: to oust the Pakistani government and impose Sharia law[15]. Most of the military’s campaigns aimed at cracking down on radicals have been targeted at weakening groups affiliated with TTP. Lastly, there are those groups with whom some branches of the Pakistani government directly collaborate with.

Pakistan has been known to use jihadi organizations to advance its security objectives through proxy conflicts. Pakistan’s policy of waging war through terrorist groups is planned, coordinated, and conducted by the Pakistani Army, specifically the ISI[16] who, as previously mentioned, plays a vital role in running the State.

Although this has been a longstanding cause of tension between the Pakistani and the American governments, the U.S. has made no progress in persuading or compelling the Pakistani military to sever ties with the radical groups[17], even though the Pakistani government has stated that it has, over the past year, ‘fought and eradicated the menace of terrorism from its soil’ by carrying out arrests, seizing property and freezing bank accounts of groups proscribed by the United States and the United Nations[18]. Their actions have been enough to keep them off the FATF’s blacklist for financing terrorism and money laundering[19], which would prevent them from getting financing, but concerns remain about ISI’s involvement with radical groups, the future of the relations between them, the overall activity of these groups from within Pakistani territory, and the risk of a future attack to its neighbours.

We will use two of Pakistan’s main proxy groups, Lashkar-e-Tayyiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad, to analyse the feasibility of an attack in the near future.

1.1. Lashkar-e-Tayyiba (LeT)

Created to support the resistance against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, LeT now focuses on the insurgencies in Afghanistan and Kashmir, the highest priorities for the Pakistani military’s foreign policy. The Ahl-e-Hadith group is led by its founder, Hafiz Saeed. Its headquarters are in Punjab. Unlike its counterparts, it is a well-organized, unified, and hierarchical organization, which has become highly institutionalized in the last thirty years. As a result, it has not suffered any major losses or any fractures since its inception[20].

Since the Mumbai attacks in 2008 (which also involved ISI), for which LeT were responsible, its close relationship with the military has defined the group’s operations, most noticeably by restraining their actions in India, which reflects both the Pakistani military’s desire to avoid international pressure and conflict with their neighbour and the group’s capability to contain its members. The group has calibrated its activities, although it possesses the capability to expand its violence. Its outlets for violence have been Afghanistan and Kashmir, which align with the Pakistani military’s agenda: to bring Afghanistan under Pakistan’s sphere of influence while keeping India off-balance in Kashmir[21]. The recent U.S.-Taliban deal in Afghanistan and militarization of Kashmir by India may change this. LeT has benefitted handsomely for its loyalty, receiving unparalleled protection, patronage, and privilege from the military. However, after twelve years of restraint, Lashkar undoubtedly faces pressures from within its ranks to strike against India again, especially now that Narendra Modi is prime minister.

1.2. Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM)

The Deobandi organization, led by its founder Masood Azhar, has had close bonds with Al-Qaeda and the Taliban since they came into light in 2000. With the commencement of the war on terror in Afghanistan, JeM reciprocated by launching an attack on the Indian Parliament on December 2001, in cooperation with LeT. However, it ignored the Pakistani military’s will in 2019 when it launched the Pulwama attack, after which the government of Pakistan launched a countrywide crackdown on them, taking leaders and members into preventive custody[22].

1.3. Risk assessment

Although it has gone rogue before, Jaish-e-Muhammad has been weakened by the recent government’s crackdown. What remains of the group, consolidated under Masood Azhar, has repaired ties with the military. Although JeM has demonstrated it still possesses formidable capability in Indian Kashmir, Lashkar-e-Tayyiba represents the main concern for an attack on India in the near future.

Lashkar has been both the most reliable and loyal of all the proxy groups and has also proven it does not take major action without prior approval from the ISI, which could become a problem. Pakistan has adopted a policy of maintaining plausible deniability for any attacks in order to avoid international pressure after 9/11, thus LeT’s close ties with the military make it more likely that its actions will provoke a war between the two countries.

The United States has tried for several years to get Pakistan to stop using proxies. There are several scenarios in which Lashkar would break from the Pakistani state (or vice versa), but they are farfetched and beyond foreign influence: a) a change in Pakistan’s security calculus, b) a resolution on Kashmir, c) a shift in Lashkar’s responsiveness and d) a major Lashkar attack in the West[23].

a) A change in Pakistan’s security calculus is the least likely, as the India-centric understanding of Pakistan’s interests and circumstances is deeply embedded in the psyche of the security establishment[24].

b) A resolution on Kashmir would trouble Lashkar, who seeks full unification of all Kashmir with Pakistan, which would not be the outcome of a negotiated resolution. More so, Modi’s recent decision regarding article 370 puts this possibility even further into the future.

c) A shift in Lashkar responsiveness would be caused by the internal pressures to perform another attack, after more than a decade of abiding by the security establishment’s will. If perceived as too powerful of insufficiently responsive, ISI would most likely seek to dismantle the group, as they did with Jaish-e-Muhammad, by focusing on the rogue elements and leaving Lashkar smaller but more responsive. This presents a threat, as the group would not allow itself to be simply dismantled but would probably resist to the point of becoming hostile[25].

d) The last option, a major Lashkar attack in the West, is also unlikely, as the group has not undertaken any major attack without perceived greenlight from ISI.

This does not mean that an attack from LeT can be ruled out. ISI could allow the group to carry out an attack if, in the absence of a better reason, it feels that the pressure from within the group will start causing dissent and fractures, just like it happened in 2008. It is in ISI’s best interest that Lashkar remains a strong, united ally. Knowing this, it is important to note that a large-scale attack in India by Lashkar is arguably the most likely trigger to a full-blown conflict between the two nations. Even a smaller-scale attack has the potential of provoking India, especially under Modi.

If such an attack where to happen, India would not be expected to display a weak-kneed gesture, as PM Modi’s policy is that of a tough and powerful approach in defence vis-à-vis both Pakistan and China. This has already been made evident by its retaliation for the Fidayeen attack at Uri brigade headquarters by Jaish-e-Muhammad in 2016[26]. It has now become evident that if Pakistan continues to harbour terrorist groups against India as its strategic assets, there will be no military restraint by India as long as Modi is in power, who will respond with massive retaliation. In its fragile economic condition, Pakistan will not be able to sustain a long-drawn war effort[27].

On the other hand, Afghanistan, which has been the other focus of Pakistan’s proxy groups, is now undergoing a process which could result in a major organizational shift. The Taliban insurgent movement has been able survive this long due to the sanctuary and support provided by Pakistan[28]. Furthermore, Lashkar-e-Tayyiba’s participation in the Afghan insurgency furthered the Pakistani military’s goal of having a friendly, anti-India partner on its western border[29]. The development and outcome of the intra-Afghan talks will determine the continued use of proxies in the country. However, we can realistically assume that, at least in the near future, radical groups will maintain some degree of activity in Afghanistan.

It is highly unlikely that the Pakistani intelligence establishment will stop engaging with radical groups, as it sees in them a very useful strategic tool for achieving its security goals. However, Pakistan’s plausible deniability approach will come into question, as its close ties with Lashkar-e-Tayyiba make it increasingly hard for it to deny involvement in its acts with any credibility. Regarding India, any kind of offensive from this group could result in a large-scale conflict. This is precisely the most likely scenario to occur, as Modi’s history with Lashkar-e-Tayyiba and their twelve-year-long “hiatus” from impactful attacks could propel the organization to take action that will impact the whole region.

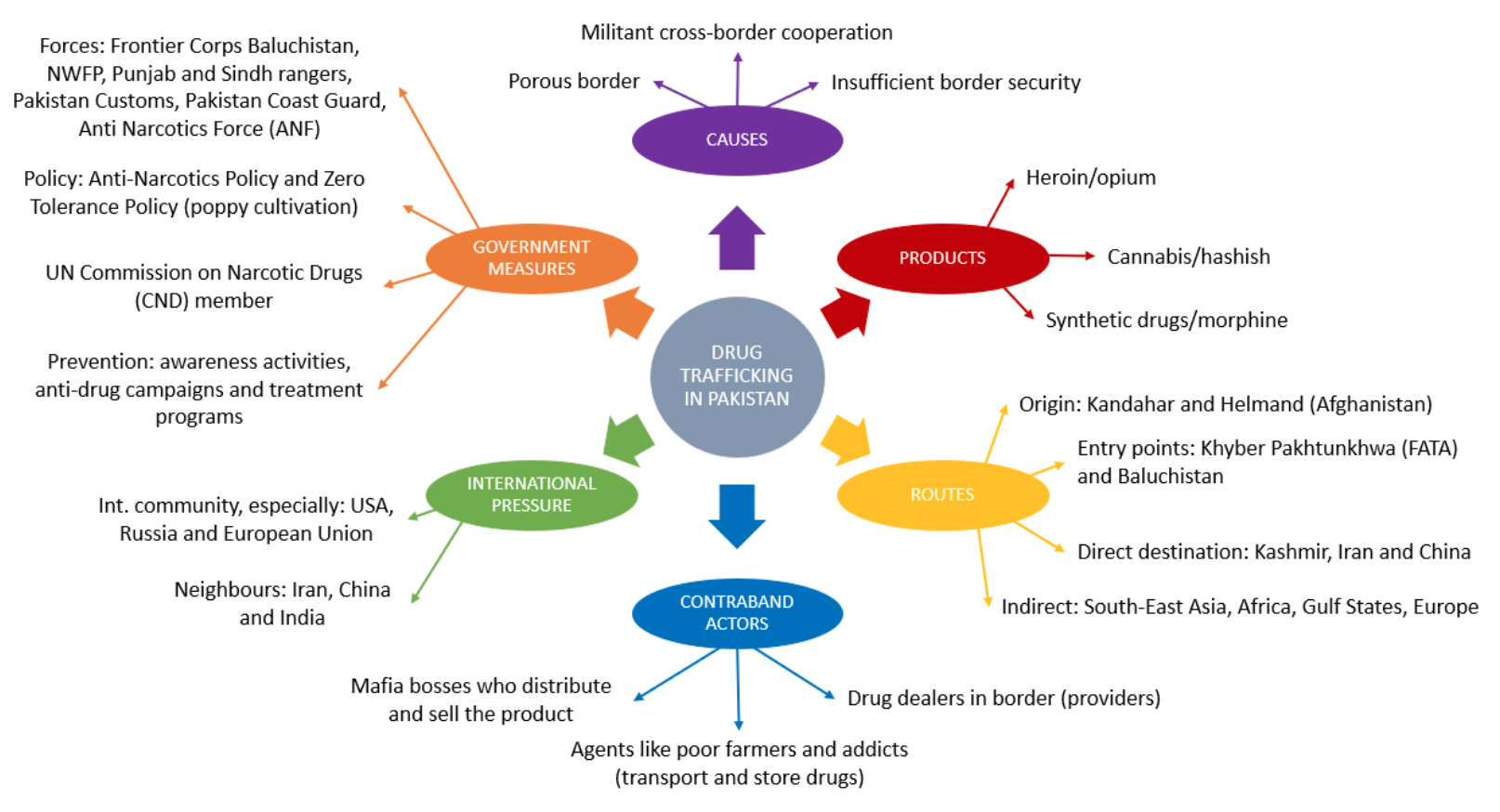

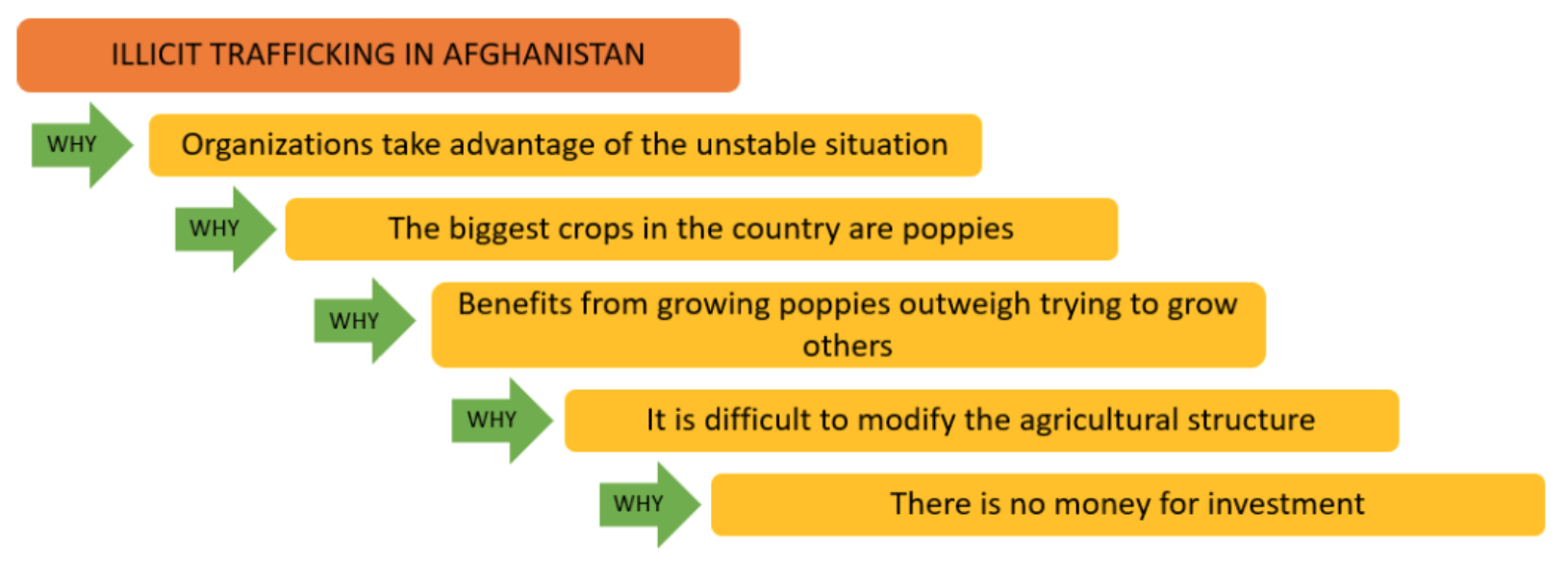

2. DRUG TRAFFICKING

Drug trafficking constitutes an important problem for Pakistan. It originates in Afghanistan, from where thousands of tonnes are smuggled out every year, using Pakistan as a passageway to provide the world with heroin and opioids[30]. The following concept map has been elaborated with information from diverse sources[31] to present the different aspects of the problem aimed to better comprehend the complex situation.

Afghanistan, one of the world’s largest heroin producers, has supplied up to 60% and 80% of the U.S. and European markets, respectively. The landlocked country takes advantage of its blurred border line, and the remoteness and inaccessibility of the sparsely populated bordering regions with Pakistan, using it as a conduct to send its drugs globally. The Pakistani government is under a lot of pressure from the international community to fight and minimize drug trafficking from its territory.

Pakistan feels a special kind of pressure from the European Union, as its GSP+ status could be affected if it does not control this problem. The GSP+ is dependent on the implementation of 27 international conventions related to human rights, labour rights, protection of the environment and good governance, including the UN Convention on Fighting Illegal Drugs[32]. Pakistan was granted GSP+ status in 2014 and has shown commitment to maintaining ratifications and meeting reporting obligations to the UN Treaty bodies[33]. However, one of the aspects of the scheme is its “temporary withdrawal and safeguard” measure, which means the preferences can be immediately withdrawn if the country is unable to control drug trafficking effectively[34]. This has not been the case, and the EU has recognized Pakistan’s efforts in the fight on drugs; the UN has also removed it from the list of cannabis resin production countries[35]. Anti-corruption frameworks have been strengthened, along with legislation review and awareness building, but they have been advised that better coordination between law enforcement agencies is needed[36].

The GSP+ status is very important to Pakistan, as the European Union is their first trade partner, absorbing over a third of their total exports in 2018, followed by the U.S., China and Afghanistan[37]. The Union can use this as leverage to obtain concessions from Pakistan. However, the approach they have taken so far has been of collaboration in many areas, including transnational organized crime, money laundering and counter-narcotics[38]. In this sense, the EU ambassador to Pakistan recently stated that the new Strategic Engagement Plan of 2019 would “further boost their relations in diverse fields”[39].

Even with combined efforts, erradicating the drug trafficking problem in Pakistan has proven to be very difficult. This is because production of the drug is not done in its territory, and even if border patrols are strengthened, it will be very hard to stop drugs from coming in from its neighbour if the Afghan government doesn’t take appropriate measures themselves.

A “5 whys” exercise has led us to understand that the root cause of the problem is the fact that most farmers in Afghanistan are too poor to turn to different crops. A nearly two decade war has ravaged the country’s land, leaving opium crops, which are cheaper and easier to maintain, as the only option for most farmers in this agrarian nation. A substantial investment in the country’s agriculture to produce more economic options would be needed if any serious advance is expected to be made in stopping illegal drug trafficking. These investments will have to be a joint effort of the international community, and funding for the government will also be necessary, if stability is to be reached. Unless this is done, opium will likely remain entangled in the rural economy, the Taliban insurgency, and the government corruption whose sum is the Afghan conundrum[40]. And as long as this does not happen, it is highly unlikely that Pakistan will be able to make any substantial progress in its effort to fight illicit drugs.

[1] Khurshid Khan and Afifa Kiran, “Emerging Tendencies of Radicalization in Pakistan,” Strategic Studies, vol. 32, 2012.

[2] Hassan N. Gardezi, “Pakistan: The Power of Intelligence Agencies,” South Asia Citizenz Web, 2011, http://www.sacw.net/article2191.html.

[3] Madiha Afzal, “Saudi Arabia’s Hold on Pakistan,” 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/research/saudi-arabias-hold-on-pakistan/.

[4] Gardezi, “Pakistan: The Power of Intelligence Agencies.”

[5] Ibid.

[6] Myriam Renaud, “Pakistan’s Plan to Reform Madrasas Ignores Why Parents Enrol Children in First Place,” The Globe Post, May 20, 2019, https://theglobepost.com/2019/05/20/pakistan-madrasas-reform/.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Drazen Jorgic and Asif Shahzad, “Pakistan Begins Crackdown on Mlitant Groups amid Global Pressure,” Reuters, March 5, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-kashmir-pakistan-un/pakistan-begins-crackdown-on-militant-groups-amid-global-pressure-idUSKCN1QM0XD.

[9] Saad Sayeed, “Pakistan Plans to Bring 20,000 Madrasas under Government Control,” Reuters, April 29, 2019.

[10] Renaud, “Pakistan’s Plan to Reform Madrasas Ignores Why Parents Enrol Children in First Place.”

[11] International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clininc (Stanford Law Review) and Global Justice Clinic (NYE School of Law), “Living Under Drones: Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians From US Drone Practices in Pakistan,” 2012, https://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/default/files/publication/313671/doc/slspublic/Stanford_NYU_LIVING_UNDER_DRONES.pdf.

[12] Saba Noor, “Radicalization to De-Radicalization: The Case of Pakistan,” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 5, no. 8 (2013): 16–19.

[13] Muhammad Iqbal Roy and Abdul Rehman, “Pakistan’s Counter Terrorism Strategy (2001-2019): Evolution, Paradigms, Prospects and Challenges,” Journal of Politics and International Studies 5, no. July-December (2019): 1–13.

[14] Madiha Afzal, “A Country of Radicals? Not Quite,” in Pakistan Under Siege: Extremism, Society, and the State (Brookings Institution Press, 2018), 208, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/chapter-one_-pakistan-under-siege.pdf.

[15] Ibid.

[16] John Crisafulli et al., “Recommendations for Success in Afghanistan,” 2019, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep20107.7.

[17] Tricia Bacon, “The Evolution of Pakistan’s Lashkar-e-Tayyiba,” Orbis, no. Winter (2019): 27–43.

[18] Susannah George and Shaiq Hussain, “Pakistan Hopes Its Steps to Fight Terrorism Will Keep It off a Global Blacklist,” The Washington Post, February 21, 2020.

[19] Husain Haqqani, “FAFT’s Grey List Suits Pakistan’s Jihadi Ambitions. It Only Worries Entering the Black List,” Hudson Institute, February 28, 2020.

[20] Bacon, “The Evolution of Pakistan’s Lashkar-e-Tayyiba.”

[21] Ibid.

[22] Farhan Zahid, “Profile of Jaish-e-Muhammad and Leader Masood Azhar,” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 11, no. 4 (2019): 1–5, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26631531.

[23] Tricia Bacon, “Preventing the Next Lashkar-e-Tayyiba Attack,” The Washington Quarterly 42, no. 1 (2019): 53–70.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Abhinav Pandya, “The Future of Indo-Pak Relations after the Pulwama Attack,” Perspectives on Terrorism 13, no. 2 (2019): 65–68, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26626866.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Crisafulli et al., “Recommendations for Success in Afghanistan.”

[29] Bacon, “The Evolution of Pakistan’s Lashkar-e-Tayyiba.”

[30] Alfred W McCoy, “How the Heroin Trade Explains the US-UK Failure in Afghanistan,” The Guardian, January 9, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/jan/09/how-the-heroin-trade-explains-the-us-uk-failure-in-afghanistan.

[31] Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray and Dr. Shanthie Mariet D Souza, “The Afghanistan-India Drug Trail - Analysis,” Eurasia Review, August , https://www.eurasiareview.com/02082019-the-afghanistan-india-drug-trail-analysis/; Mehmood Hassan Khan, “Kashmir and Power Politics,” Defence Journal 23, no. 2 (2019); McCoy, “How the Heroin Trade Explains the US-UK Failure in Afghanistan”; Pakistan United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Country Office, “Illicit Drug Trends in Pakistan,” 2008, https://www.unodc.org/documents/regional/central-asia/Illicit Drug Trends Report_Pakistan_rev1.pdf; “Country Profile - Pakistan,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2020, https://www.unodc.org/pakistan/en/country-profile.html.

[32] European Commission, “Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP),” 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/development/generalised-scheme-of-preferences/.

[33] High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, “The EU Special Incentive Arrangement for Sustainable Development and Good Governance ('GSP+’) Assessment of Pakistan Covering the Period 2018-2019” (Brussels, 2020).

[34] Dr. Zobi Fatima, “A Brief Overview of GSP+ for Pakistan,” Pakistan Journal of European Studies 34, no. 2 (2018), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333641020_A_BRIEF_OVERVIEW_OF_GSP_FOR_PAKISTAN.

[35] High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, “The EU Special Incentive Arrangement for Sustainable Development and Good Governance ('GSP+’) Assessment of Pakistan Covering the Period 2018-2019.”

[36] Fatima, “A Brief Overview of GSP+ for Pakistan.”

[37] UN Comtrade Analytics, “Trade Dashboard,” accessed March 27, 2020, https://comtrade.un.org/labs/data-explorer/.

[38] European External Action Services, “EU-Pakistan Five Year Engagement Plan” (European Union, 2017), https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eu-pakistan_five-year_engagement_plan.pdf; European Union External Services, “EU-Pakistan Strategic Engagement Plan 2019” (European Union, 2019), https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eu-pakistan_strategic_engagement_plan.pdf.

[39] “EU Ready to Help Pakistan in Expanding Its Reports: Androulla,” Business Recorder, October 23, 2019.

[40] McCoy, “How the Heroin Trade Explains the US-UK Failure in Afghanistan.”

![Prime Minister Imran Kahn, at the United Nations General Assembly, in 2019 [UN] Prime Minister Imran Kahn, at the United Nations General Assembly, in 2019 [UN]](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-introduccion-blog.jpg)

▲ Prime Minister Imran Kahn, at the United Nations General Assembly, in 2019 [UN]

ESSAY / M. Biera, H. Labotka, A. Palacios

The geographical location of a country is capable of determining its destiny. This is the thesis defended by Whiting Fox in his book "History from a Geographical Perspective". In particular, he highlights the importance of the link between history and geography in order to point to a determinism in which a country's aspirations are largely limited (or not) by its physical place in the world.[1]

Countries try to overcome these limitations by trying to build on their internal strengths. In the case of Pakistan, these are few, but very relevant in a regional context dominated by the balance of power and military deterrence.

The first factor that we highlight in this sense is related to Pakistan's nuclear capacity. In spite of having officially admitted it in 1998, Pakistan has been a country with nuclear capacity, at least, since Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's government started its nuclear program in 1974 under the name of Project-706 as a reaction to the once very advanced Indian nuclear program.[2]

The second factor is its military strength. Despite the fact that they have publicly refused to participate in politics, the truth is that all governments since 1947, whether civil or military, have had direct or indirect military support.[3] The governments of Ayub Khan or former army chief Zia Ul-Haq, both through a coup d'état, are faithful examples of this capacity for influence.[4]

The existence of an efficient army provides internal stability in two ways: first, as a bastion of national unity. This effect is quite relevant if we take into account the territorial claims arising from the ethnic division caused by the Durand Line. Secondly, it succeeds in maintaining the state's monopoly on force, preventing its disintegration as a result of internal ethnic disputes and terrorism instigated by Afghanistan in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA region).[5]

Despite its internal strengths, Pakistan is located in one of the most insecure geographical areas in the world, where border conflicts are intermingled with religious and identity-based elements. Indeed, the endless conflict over Kashmir against India in the northeastern part of the Pakistani border or the serious internal situation in Afghanistan have been weighing down the country for decades, both geo-politically and economically. The dynamics of regional alliances are not very favourable for Pakistan either, especially when US preferences, Pakistan's main ally, seem to be mutating towards a realignment with India, Pakistan's main enemy.[6]

On the positive side, a number of projects are underway in Central Asia that may provide an opportunity for Pakistan to re-launch its economy and obtain higher standards of stability domestically. The most relevant is the New Silk Road undertaken by China. This project has Pakistan as a cornerstone in its strategy in Asia, while it depends on it to achieve an outlet to the sea in the eastern border of the country and investments exceeding 11 billion dollars are expected in Pakistan alone[7]. In this way, a realignment with China can help Pakistan combat the apparent American disengagement from Pakistani interests.

For all these reasons, it is difficult to speak of Pakistan as a country capable of carving out its own destiny, but rather as a country held hostage to regional power dynamics. Throughout this document, a review of the regional phenomena mentioned will be made in order to analyze Pakistan's behavior in the face of the different challenges and opportunities that lie ahead.

History

Right after the downfall of the British colony of the East Indies colonies in 1947 and the partition of India the Dominion of Pakistan was formed, now known by the title of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. The Partition of India divided the former British colony into two separated territories, the Dominion of Pakistan and the Dominion of India. By then, Pakistan included East Pakistan (modern day) Pakistan and Oriental Pakistan (now known as Bangladesh).

It is interesting to point out that the first form of government that Pakistan experienced was something similar to a democracy, being its founding father and first Prime Minister Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Political history in Pakistan consists of a series of eras, some democratically led and others ruled by the military branch which controls a big portion of the country.

—The rise of Pakistan as a Muslim democracy: 1957-1958. The era of Ali Jinnah and the First Indo-Pakistani war.

—In 1958 General Ayub Khan achieved to complete a coup d’état in Pakistan due to the corruption and instability.

—In 1971 General Khan resigned his position and appointed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto as president, but, lasted only 6 years. The political instability was not fruitful and rivalry between political parties was. But in 1977 General Zia-ul-Haq imposed a new order in Pakistan.

—From 1977 to 1988 Zia-ul-Haq imposed an Islamic state.

—In the elections of 1988 right after Zia-ul-Haq’s death, President Benazir Bhutto became the very first female leader of Pakistan. This period, up to 1999 is characterized by its democracy but also, by the Kargil War.

—In 1999 General Musharraf took control of the presidency and turned it 90º degrees, opening its economy and politics. In 2007 Musharraf announced his resignation leaving open a new democratic era characterized by the War on Terror of the United States in Afghanistan and the Premiership of Imran Khan.

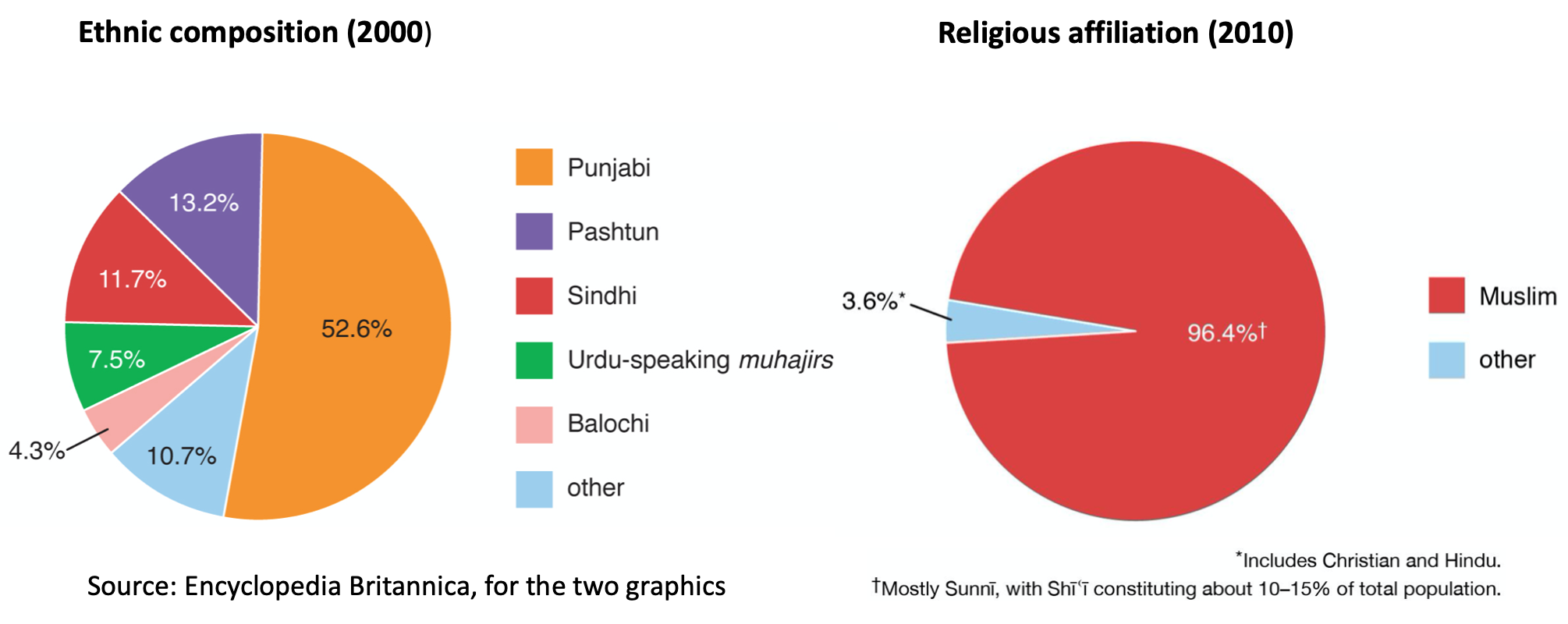

Human and physical geography

The capital of Pakistan is Islamabad, and as of 2012 houses a population of 1,9 million people. While the national language of Pakistan is English, the official language is Urdu; however, it is not spoken as a native language. Afghanistan is Pakistan’s neighbor to the northwest, with China to the north, as well as Iran to the west, and India to the east and south.[8]

Pakistan is unique in the way that it possesses many a geological formation, like forests, plains, hills, etcetera. It sits along the Arabian Sea and is home to the northern Karakoram mountain range, and lies above Iranian, Eurasian and Indian tectonic plates. There are three dominant geographical regions that make up Pakistan: the Indus Plain, which owes its name to the river Indus of which Pakistan’s dominant rivers merge; the Balochistan Plateau, and the northern highlands, which include the 2nd highest mountain peak in the world, and the Mount Godwin Austen.[9] Pakistan’s traditional regions are a consequence of progression. These regions are echoed by the administrative distribution into the provinces of Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa which includes FATA (Federally Administered Tribal Areas) and Balochistan.

Each of these regions is “ethnically and linguistically distinct.”[10] But why is it important to understand Pakistan’s geography? The reason is, and will be discussed further in detail in this paper, the fact that “terror is geographical” and Pakistan is “at the epicenter of the neo-realist, militarist geopolitics of anti-terrorism and its well-known manifestation the ‘global war on terror’...”[11]

Punjabi make up more than 50% of the ethnic division in Pakistan, and the smallest division is the Balochi. We should note that Balochistan, however small, is an antagonistic region for the Pakistani government. The reason is because it is a “base for many extremist and secessionist groups.” This is also important because CPEC, the Chinese-Pakistan Economic Corridor, is anticipated to greatly impact the area, as a large portion of the initiative is to be constructed in that region. The impact of CPEC is hoped to make that region more economically stable and change the demography of this region.[12]

The majority of Pakistani people are Sunni Muslims, and maintain Islamic tradition. However, there is a significant number of Shiite Muslims. Religion in Pakistan is so important that it is represented in the government, most obviously within the Islamic Assembly (Jamāʿat-i Islāmī) party which was created in 1941.[13]

This is important. The reason being is that there is a history of sympithism for Islamic extremism by the government, and giving rise to the expansion of the ideas of this extremism. Historically, Pakistan has not had a strict policy against jihadis, and this lack of policy has poorly affected Pakistan’s foreign policy, especially its relationship with the United States, which will be touched upon in this paper.

Current Situation: Domestic politics, the military and the economy

Imran Khan was elected and took office on August 18th, 2018. Before then, the previous administrations had been overshadowed by suspicions of corruption. What also remained important was the fact that his election comes after years of a dominating political power, the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) and Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). Imran Khan’s party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) surfaced as the majority in the Pakistan’s National Assembly. However, there is some debate by specialists on how prepared the new prime minister is to take on this extensive task.

Economically, Pakistan was in a bad shape even before the global Coronavirus-related crisis. In October 2019, the IMF predicted that the country's GDP would increase only 2.4% in 2020, compared with 5,2% registered in 2017 and 5,5% in 2018; inflation would arrive to 13% in 2020, three times the registered figure of 2017 and 2018, and gross debt would peak at 78.6%, ten points up from 2017 and 2018.[14] This context led to the Pakistani government to ask for a loan to the IMF, and a $6 billion loan was agreed in July 2019. In addition, Pakistan got a $2 billion from China. Later on, because of the Covid-19 pandemic, the IMF worsened its estimations on Pakistan's economy, and predicted that its GDP would grow minus 1.5% in 2020 and 2% in 2021.[15]

Throughout its history, Pakistan has been a classic example of a “praetorian state”, where the military dominates the political institutions and regular functioning. The political evolution is represented by a routine change “between democratic, military, or semi military regime types.” There were three critical pursuits towards a democratic state that are worth mentioning, that started in 1972 and resulted in the rise of democratically elected leaders. In addition to these elections, the emergence of new political parties also took place, permitting us to make reference to Prime Minister Imran Khan’s party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI).[16]

Civilian - military relations are characterized by the understanding that the military is what ensures the country’s “national sovereignty and moral integrity”. There resides the ambiguity: the intervention of the military regarding the institution of a democracy, and the sabotage by the same military leading it to its demise. In addition to this, to the people of Pakistan, the military has retained the impression that the government is incapable of maintaining a productive and functioning state, and is incompetent in its executing of pertaining affairs. The role of the military in Pakistani politics has hindered any hope of the country implementing a stable democracy. To say the least, the relationship between the government and the resistance is a consistent struggle.[17]

The military has extended its role today with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. The involvement of the military has affected “four out of five key areas of civilian control”. Decision making was an area that was to be shared by the military and the people of Pakistan, but has since turned into an opportunity for the military to exercise its control due to the fact that CPEC is not only a “corporate mega project” but also a huge economic opportunity, and the military in Pakistan continues to be the leading force in the creation of the guidelines pertaining to national defense and internal security. Furthermore, accusations of corruption have not helped; the Panama Papers were “documents [exposing] the offshore holdings of 12 current and former world leaders.”[18] These findings further the belief that Pakistan’s leaders are incompetent and incapable of effectively governing the country, and giving the military more of a reason to continue and increase its interference. In consequence, the involvement of civilians in policy making is declining steadily, and little by little the military seeks to achieve complete autonomy from the government, and an increased partnership with China. It is safe to say that CPEC would have been an opportunity to improve military and civilian relationships, however it seems to be an opportunity lost as it appears the military is creating a government capable of functioning as a legitimate operation.[19]

[1] Gottmann, J., & Fox, E. W. (1973). History in Geographic Perspective: The Other France. Geographical Review.

[2] Tariq Ali (2009). The Duel: Pakistan on the Flight Path of American Power

[3] Marquina, A. (2010). La Política de Seguridad y Defensa de la Unión Europea. 28, 441–446.

[4] Tariq Ali (2009). Ibíd.

[5] Sánchez de Rojas Díaz, E. (2016). ¿Es Paquistán uno de los países más conflictivos del mundo? Los orígenes del terrorismo en Paquistán.

[6] Ríos, X. (2020). India se alinea con EE.UU.

[7] Economic corridor: China to extend assistance at 1.6 percent interest rate. (2015). Business Recorder.

[8] Szczepanski, Kallie. "Pakistan | Facts and History." ThoughtCo.

[9] Pakistan Insider. “Pakistan's Geography, Climate, and Environment.” Pakistan Insider, February 9, 2012.

[10] Burki, Shahid Javed, and Lawrence Ziring. “Pakistan.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., March 6, 2020.

[11] Mustafa, Daanish, Nausheen Anwar, and Amiera Sawas. “Gender, Global Terror, and Everyday Violence in Urban Pakistan.” Elsevier. Elsevier Ltd., December 4, 2018

[12] Bhattacharjee, Dhrubajyoti. “China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).” Indian Council of World Affairs, May 12, 2015

[13] Burki, Shahid Javed, and Lawrence Ziring. Ibíd.

[14] IMF, “Economic Outlook”, October 2019.

[15] IMF, “World Economic Outlook”, April 2020.

[16] Wolf, Siegfried O. “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, Civil-Military Relations and Democracy in Pakistan.” SADF Working Paper, no. 2 (September 13, 2016)

[17] Ibíd.

[18] “Giant Leak of Offshore Financial Records Exposes Global Array of Crime and Corruption.” The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, April 3, 2016.

[19] Wolf, Siegfried O. Ibíd.

[Edgar A. Porter & Ran Yin Porter, Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation. Amsterdam University Press. Amsterdam, 2017. 256 p.]

REVIEW / Rut Natalie Noboa Garcia

World War II has provided much inspiration for an entire genre of literature. However, few works fail to capture Asian perspectives on the beginning, development, end, and consequences of World War II. Additionally, the attitude and outlooks of defeated parties are often left out of popularized discussions of conflicts. Because of these two factors, Japanese perspectives during the war and occupation have often served as only minor discussions in World War II literary work.

World War II has provided much inspiration for an entire genre of literature. However, few works fail to capture Asian perspectives on the beginning, development, end, and consequences of World War II. Additionally, the attitude and outlooks of defeated parties are often left out of popularized discussions of conflicts. Because of these two factors, Japanese perspectives during the war and occupation have often served as only minor discussions in World War II literary work.

This sets the stage for Edgar A. Porter and Rin Ying Porter’s Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation, which presents the experiences of ordinary Japanese citizens during the period. The book specifically focuses on the rural Oita prefecture, located on the eastern coast of the island of Kyushu, a crucial yet critically unacknowledged place in Japan’s role in World War II. Hosting the Imperial Japanese Navy base that served as the headquarters for the Pearl Harbor attack, being the hometown of the two Japanese representatives that signed the terms of surrender at the USS Battleship Missouri, serving as the place for the final kamikaze attack against the United States, and providing much of Japan’s foot soldiers for the conflict, Oita is ripe with unchronicled, raw, and diverse accounts of the Japanese experience.