Breadcrumb

Blogs

[Admiral James Stavridis, Sea Power. The History and Geopolitics of the World's Oceans. Penguin Press. New York City, 2017. 363 páginas]

19 de enero, 2018

RESEÑA / Iñigo Bronte Barea [Versión en inglés]

En la era de la globalización y su sociedad de la comunicación, donde todo está más cerca y las distancias parecen desvanecerse, la masa de agua entre los continentes no ha perdido el valor estratégico que siempre ha tenido. Históricamente los mares han sido tanto cauce para el desarrollo humano como instrumentos de dominio geopolítico. No es coincidencia que las grandes potencias mundiales de los últimos 200 años hayan sido a su vez grandes potencias navales. La disputa por el espacio marítimo la seguimos viviendo en el momento actual y nada sugiere que la geopolítica de los mares vaya a dejar de ser crucial en el futuro.

Poco han variado esos principios sobre la importancia de las potencias marítimas desde que fueran expuestos a finales del siglo XIX por Alfred T. Mahan. De su vigencia habla hoy Sea Power. The History and Geopolitics of the World's Oceans, del almirante James G. Stavridis, retirado en 2013 después de haber dirigido el Comando Sur de Estados Unidos, el Mando Europeo estadounidense y la jefatura suprema de la OTAN.

El libro es fruto precisamente de tempranas lecturas de Mahan y de una dilatada carrera de casi cuatro décadas recorriendo los mares y océanos con la marina estadounidense. Al iniciar cada explicación sobre los distintos espacios marinos, Stavridis relata su breve experiencia en dicho mar u océano, para luego seguir con la historia, y el desarrollo que han tenido, hasta llegar a su contexto actual. Finalmente hay una proyección sobre el futuro próximo que tendrá el mundo desde la perspectiva de la geopolítica marina.

Pacífico: la emergencia de China

El Almirante J. G. Stavridis comienza su viaje por el Océano Pacífico, al que categoriza como “la madre de todos los océanos” debido a su inmensidad, ya que, él solo, es más grande que toda la superficie terrestre del planeta combinada. Otro punto reseñable es que en su inmensidad no hay ninguna masa terrestre considerable, aunque sí que hay islas de todo tipo, con muy diversas culturas. Por eso el mar domina la geografía del Pacífico como no lo hace en ningún otro lugar del planeta.

|

El gran dominador de este espacio marino es Australia, que se encuentra muy pendiente de lo que pueda pasar políticamente en los archipiélagos de islas de sus cercanías. Fueron sin embargo los europeos quienes exploraron bien el Pacífico (Magallanes fue el primero, hacia 1500) e intentaron conectarlo con su mundo de manera no meramente transitoria y comercial, sino estable y duradera.

Estados Unidos comenzó a estar presente en el Pacífico desde la adquisición de California (1840), pero no fue hasta la anexión de Hawái (1898) que el inmenso país se vio catapultado definitivamente hacia el Pacífico. La primera vez que este océano emergió como zona de guerra total fue en 1941 cuando Pearl Harbour fue masacrado por los japoneses.

Con el retorno de la paz, el reavivamiento japonés y la emergencia de China, Taiwán, Corea, Singapur y Hong Kong hicieron que el comercio transpacífico sobrepasara por primera vez al Atlántico en la década de 1980, y esta tendencia todavía continúa. Esto es así porque la región del Pacífico contiene a las mayores potencias mundiales en sus costas.

En el área geopolítica una gran carrera armamentística se está llevando a cabo en el Pacífico, con Corea del Norte como gran foco de tensión e incertidumbre a nivel mundial.

Atlántico: del Canal de Panamá a la OTAN

En cuanto al Océano Atlántico, Stavridis se refiere a él como la cuna de la civilización, ya que se incluye al Mediterráneo entre sus territorios, y más si cabe todavía si lo consideramos como el nexo entre las gentes de toda América y África con Europa. Posee dos grandes mares de suma importancia histórica como son el Caribe y el Mediterráneo.

Sin duda alguna la figura histórica de este océano es la de Cristóbal Colón, ya que con su llegada a América (Bahamas 1492) inició un nuevo periodo histórico que acabó con prácticamente todo el continente americano colonizado por las potencias europeas en los siglos posteriores. Mientras que Portugal y España se concentraron en el Caribe y Suramérica, los británicos y los franceses lo hicieron en Norteamérica.

Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial el Atlántico se convirtió en una zona de tránsito esencial para el desarrollo de la guerra, ya que, a través de él Estados Unidos llevó a sus tropas, materiales de guerra y mercancías a Europa durante el conflicto. Fue aquí cuando se empezó a gestar la idea de una comunidad de los países atlánticos que acabaría desembocando en la creación de la OTAN.

En cuanto al Caribe, el autor lo considera como una región instalada en el pasado. Su colonización estuvo caracterizada por la llegada de esclavos para explotar los recursos naturales de la región con fines de interés económico para los españoles. A su vez este proceso estuvo caracterizado por el deseo de convertir a la población indígena al cristianismo.

El Canal de Panamá supone un motor para la economía de la región, pero en América Central también se navega por las costas de los países con las tasas de violencia más elevadas del planeta. El almirante Stavridis considera a la costa caribeña como una especie de Salvaje Oeste que en algunos lugares ha evolucionado poco desde los tiempos de los piratas, y en los que actualmente actúan los cárteles de la droga con total impunidad.

Desde la década de 1820, con la Doctrina Monroe, Estados Unidos llevó a cabo una serie de intervenciones a través de su marina para reforzar la estabilidad regional y dejar a los europeos fuera de lugares tales como Haití, República Dominicana y Centroamérica. En el siglo XX la política estuvo dominada por caudillos, y pronto llegaron con ellos el comunismo y la Guerra Fría al Caribe, teniendo como zona cero a Cuba.

Índico y Ártico: de la incógnita al riesgo

El Océano Índico tiene menos historia y geopolítica que los otros dos grandes océanos. A pesar de esto, sus mares tributarios han ganado importancia geopolítica en la era posterior a la Segunda Guerra Mundial con el aumento de la navegación global y la exportación de petróleo de la región del Golfo. El Índico podría considerarse hoy en día como una región para ejercer poder inteligente en lugar de poder duro. Mientras la trata de esclavos y la piratería han disminuido casi hasta desaparecer en casi todas partes, todavía están presente en lugares del Océano Índico. Es una región en la que los países de todo el mundo podrían colaborar juntos para luchar contra estos problemas comunes.

La historia del Océano Índico no inspira confianza acerca del potencial de gobernanza pacífica en los años venideros. Una clave importante para desbloquear el potencial de la región sería resolver los conflictos existentes entre India y Pakistán (un conflicto con el riesgo de uso de armas nucleares) y la división chií-suní en el Golfo Pérsico, asuntos que la convierten en una región muy volátil. Debido a las tensiones de los países del Golfo, la región es hoy una especie de guerra fría entre los suníes, liderada por Arabia Saudita, y los chiíes, liderados por Irán, y entre estos dos lados, se encuentra en el centro Estados Unidos, con su Quinta Flota.

Por último, el Ártico es actualmente toda una incógnita. Stavridis considera que es a la vez una promesa y un peligro. A lo largo de los siglos, todos los océanos y mares han sido lugar de épicas batallas y de descubrimientos, pero hay una excepción: el Océano Ártico.

Parece claro que esa excepcionalidad está llegando a su fin. El Ártico es una frontera marítima emergente con actividad humana en aumento, bloques de hielo que se derriten rápidamente y, recursos de hidrocarburos de gran importancia que comienzan a estar al alcance. Sin embargo, existen grandes riesgos que condicionarán peligrosamente la explotación de esta región, como son las condiciones climatológicas, una gobernabilidad confusa debido a la confluencia de cinco países fronterizos (Rusia, Noruega, Canadá, Estados Unidos y Dinamarca), y una competición geopolítica entre la OTAN y Rusia, cuyas relaciones se están deteriorando en los últimos años.

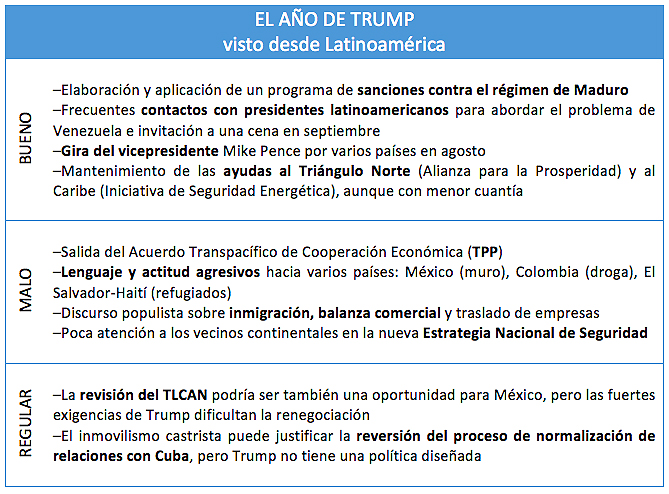

The neighbors of the United States in the Western Hemisphere find it difficult to interpret the first year of the new administration

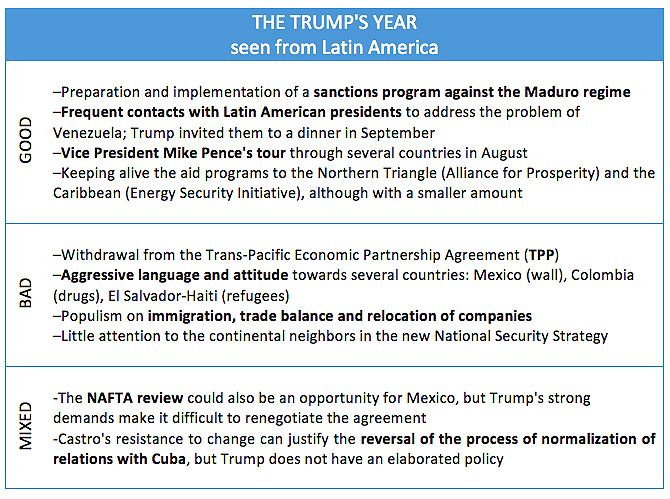

Donald Trump reaches his first anniversary as president of the United States having caused some recent fires in Latin America. His rude disregard for El Salvador and Haiti, due to the high figures of refugees sheltered in the U.S., and his harsh treatment of Colombia, for the increase in cocaine production, had damaged the relations. Although they were already complicated in the case of Mexico, throughout the year they had some good times, such as the presidents' dinner that Trump summoned in September in New York in which a united action was drawn on Venezuela.

▲Trump in his first 100 days as president [White House]

ARTICLE / Garhem O. Padilla [Spanish version]

One year after the inauguration of the 45th President of the United States of America, Donald John Trump (the ceremony was on January 20), the controversy dominates the balance of the new administration, both in his domestic as well as international performance. The continental neighbors of the United States, in particular, show bewilderment about Trump's policies towards the hemisphere. On the one hand, they regret the American disinterest in commitments of economic development and multilateral integration; on the other hand, they note some activity in relation to some regional problems, such as the Venezuelan one. The actual balance is mixed, although there is unanimity that the language and many of Trump's forms threaten relationships.

From the TPP to NAFTA

In the economic field, the Trump era started with the definitive withdrawal of the United States from the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement (TPP), on January 23, 2017. This made it impossible to enter into force since the United States is the market through which above all, this agreement emerged. The U.S. withdrawal affected the perspectives of the Latin American countries participating in the initiative.

Then, the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), demanded by Trump, was opened. The doubts about the future of the NAFTA, signed in 1994 and that Trump has described as "disaster", have stood out in what is going of the administration. Some of its demands, which Mexico and Canada oppose, are to increase the share of products manufactured in the United States, and the "sunset" clause, which would force the treaty to be reviewed methodically every five years and suspend it if any of its three members did not agree. All this, arises from the idea of the U.S. president to suspend the treaty if it is not favorable for his country.

Cuba and Venezuela

If the quarrels with Mexico have not yet reached to an end, in the case of Cuba, Trump has already retaliated against the Castro regime, with the expulsion in October of 15 Cuban diplomats from the Cuban Embassy in Washington in response to "the sonic attacks" that affected 24 U.S. diplomats on the island. The White House, in addition, has revoked some conciliatory measures of the Obama administration because the Castro regime is not responding with open-ended concessions.

As far as Venezuela is concerned, Trump has made strong efforts in terms of introducing measures and sanctions against corrupt officials, in addition to addressing the political situation with other countries, so that they support those efforts aimed at eradicating the Venezuelan crisis, thus generating multilateralism between American countries. However, this policy has detractors, who believe that the sanctions are not intended to achieve a long-term objective, and it is not clear how they would promote Venezuelan stability.

Although in those actions on Cuba and Venezuela Trump has alluded to the democratic principles violated by the governors of Havana and Caracas, his administration has not insisted especially on the commitment to human rights, democracy and moral values, as being usual in the argumentation of the U.S. foreign policy. Some critics point out that the Trump administration is willing to promote human rights only when they meet its political objectives.

This could explain the worsening of the opinion that exists in Latin America about the United States and about the relations with that country. According to the Latinobarómetro survey 2017, the favorable opinion has fallen to 67%, seven points below that at the end of the Obama administration, which was 74%. This survey shows a significant difference for Mexico, one of the countries that, without a doubt, has the worst levels of favorable opinion towards the Trump administration: in 2017 it was 48%, which means a fall of 29 points in comparison with 2016, in which it was 77%.

|

Immigration, withdrawal, decline

The restrictive immigration policies applied would also explain that rejection of the Trump administration by Latin American public opinion. In the immigration section the most recent is the decision not to renew the authorization to stay in the United States of thousands of Salvadorans and Haitians, who once entered the U.S. fleeing calamities in their countries.

We must also allude to Trump's efforts to achieve one of its main objectives since the beginning of his political campaign: to build a border wall with Mexico. The U.S. president has not had much success at this time, since although he has looked for ways to finance it, what he has managed to introduce in the budgets is very insignificant in relation to the estimated costs.

Trump's protectionism entails a withdrawal that may be accentuating the decline of the U.S. leadership in Latin America, especially against other powers. China has been increasing its economic and political performance in countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Peru and Venezuela. Russia, for its part, has strengthened diplomatic and security relations with Cuba. It could be said that, taking advantage of the conflicts between Cuba and the United States, Moscow has tried to keep the island in its orbit through a series of investments.

Threats to security

This leads us to mention the new National Security Strategy of the United States, announced in December. The document presented by Trump addresses the rivalry with China and Russia, and also refers to the challenge posed by the regimes of Cuba and Venezuela, by the supposed threats to security they represent and the support of Russia they receive. Trump expressed great desire to see Cuba and Venezuela join "shared freedom and prosperity" and called for "isolating governments that refuse to act as responsible partners in advancing hemispheric peace and prosperity."

Similarly, the new U.S. Security Strategy refers to other challenges in the region, such as transnational criminal organizations, which impede the stability of Central American countries, especially Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador. All in all, the document only dedicates one page to Latin America, in line with Washington's traditional attention given to the areas of the world that most affect their interests and security.

An opportunity for the United States to approach the Latin American countries will be the Summit of the Americas, which will be held next March in Lima. However, nothing is predictable given the characteristic attitude of the president, which leaves a large open space for possible surprises.

A los vecinos continentales de EE.UU. les cuesta interpretar el primer año de la nueva Administración

Donald Trump llega a su primer aniversario como presidente habiendo provocado algunos recientes incendios en Latinoamérica. Su maleducada desconsideración hacia El Salvador y Haití, por el volumen de refugiados acogidos en Estados Unidos, y su trato destemplado a Colombia por el aumento de producción de cocaína empeoran unas relaciones que, si bien ya nacieron complicadas en el caso de México, a lo largo del año han tenido algunos buenos momentos, como la cena de presidentes que Trump convocó en septiembre en Nueva York en la que se trazó un acción unitaria sobre Venezuela.

▲Trump, al cumplir cien días de presidente [Casa Blanca]

ARTÍCULO / Garhem O. Padilla [Versión en inglés]

Cuando se cumple un año de la llegada del 45º presidente de los Estados Unidos de América, Donald John Trump, a la Casa Blanca –la ceremonia de inauguración fue un 20 de enero–, la controversia domina el balance de la nueva Administración, tanto en su actuación doméstica como internacional. Los vecinos continentales de EE.UU., en concreto, muestran desconcierto sobre las políticas de Trump hacia el hemisferio. Por un lado, lamentan el desinterés estadounidense por compromisos de desarrollo económico e integración multilateral; por otro, constatan cierta actividad en relación a algunos problemas regionales, como el venezolano. El balance de momento es mixto, aunque hay unanimidad en que el lenguaje y muchas de las formas de Trump más bien amenazan las relaciones.

Del TPP al TLCAN

En el campo económico, la era Trump arrancó con la retirada definitiva de Estados Unidos del Acuerdo Transpacífico de Cooperación Económica (TPP), el 23 de enero de 2017. Eso imposibilitó la entrada en vigencia de este al ser Estados Unidos el mercado por el que sobre todo surgió dicho acuerdo, lo que ha afectado a las perspectivas de los países latinoamericanos que participaban en la iniciativa.

Enseguida se abrió la renegociación del Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte (TLCAN), exigida por Trump. Las dudas sobre el futuro del TLCAN, firmado en 1994 y que Trump ha calificado de "desastre", han sobresalido en lo que va de Administración. Algunas de sus exigencias, a las que México y Canadá se oponen, son la de incrementar la cuota de productos fabricados en Estados Unidos y la cláusula "sunset", que obligaría a revisar el tratado de manera metódica cada cinco años y haría que quedara suspendido si alguno de sus tres miembros no estuviera de acuerdo. Todo ello, surge a partir de la idea del presidente estadounidense de suspender el tratado si no es favorable para su país.

Cuba y Venezuela

Si las rencillas con México aún no han llegado a un desenlace, en el caso de Cuba Trump ya ha tomado represalias contra el régimen castrista, con la expulsión en octubre de 15 diplomáticos cubanos de la embajada de Cuba en Washington como respuesta ante “los ataques sónicos” que afectaron a 24 diplomáticos estadounidenses en la isla. La Casa Blanca, además, ha revocado algunas medidas conciliadoras de la Administración Obama, al comprobar que el castrismo no está respondiendo con concesiones aperturistas.

Por lo que afecta a Venezuela, Trump ha realizado esfuerzos contundentes en cuanto a introducción de medidas y sanciones contra funcionarios corruptos, además de abordar la situación política con otros países, para que estos apoyen esos esfuerzos dirigidos a erradicar la crisis venezolana, generando así multilateralidad entre países americanos. No obstante, esa política cuenta con detractores, que estiman que las sanciones no están destinadas a lograr un objetivo a largo plazo, además de que no está claro de qué manera impulsarían a la estabilidad venezolana.

Aunque en esas actuaciones sobre Cuba y Venezuela Trump ha hecho alusión a los principios democráticos conculcados por los gobernantes de La Habana y de Caracas, su Administración no ha insistido especialmente en el compromiso con los derechos humanos, la democracia y los valores morales, como venía siendo habitual en la argumentación de la política exterior norteamericana. Algunas críticas apuntan a que la Administración de Trump está dispuesta a promover los derechos humanos solo cuando se ajusten a sus objetivos políticos.

Esto podría explicar el empeoramiento de la opinión que existe en Latinoamérica sobre Estados Unidos y sobre las relaciones con ese país. De acuerdo con la encuesta Latinobarómetro 2017, la opinión favorable ha caído al 67%, siete puntos por debajo de la que había al final de la Administración Obama, que era del 74%. Dicha encuesta muestra una diferencia relevante para México, uno de los países que, sin duda alguna, tiene los peores niveles de opinión favorable hacia la Administración de Trump: en 2017 ha sido de 48%, lo que supone una caída de 29 puntos en comparación con 2016, en el que era de 77%.

|

Inmigración, repliegue, declive

Las restrictivas políticas de inmigración aplicadas también explicarían ese rechazado hacia la Administración Trump por parte de la opinión pública latinoamericana. En el apartado inmigratorio lo más reciente es la decisión de no renovar la autorización de estancia en Estados Unidos de miles de salvadoreños y haitianos, que en su día llegaron huyendo de calamidades en sus países.

También hay que hacer alusión a los esfuerzos de Trump para lograr uno de sus objetivos principales desde los inicios de su campaña política: construir un muro fronterizo con México. El presidente estadounidense no ha tenido de momento mucho éxito en este objetivo, ya que a pesar de que haber buscado formas de financiarlo, lo que ha logrado introducir en los presupuestos es muy poco significativo en relación con los costes estimados. Por otro lado, su decisión

El proteccionismo de Trump conlleva un repliegue que puede estar acentuando el declive del protagonismo estadounidense como líder en Latinoamérica, especialmente frente a otras potencias. China lleva tiempo incrementado su actuación tanto económica como política en países como Argentina, Brasil, Chile, Perú y Venezuela. Rusia, por su parte, ha estrechado sus relaciones diplomáticas y de seguridad con Cuba. Podría decirse que, aprovechando los conflictos entre la isla y Estados Unidos, Moscú ha pretendido mantenerla en su órbita mediante una serie de inversiones.

Amenazas a la seguridad

Esto nos lleva a mencionar la nueva Estrategia Nacional de Seguridad de Estados Unidos, anunciada en diciembre. El documento, presentado por Trump, aborda la rivalidad con China y con Rusia, y se refiere también al reto que suponen los regímenes de Cuba y de Venezuela, por las supuestas amenazas a la seguridad que representan y el apoyo de Rusia que reciben. Trump manifestó el gran el deseo de ver a Cuba y Venezuela unirse a la «libertad y prosperidad compartidas» y llamó a «aislar a los gobiernos que rehúsan actuar como socios responsables en avanzar la paz y prosperidad hemisférica».

De igual manera, la nueva Estrategia de Seguridad estadounidense hace alusión a otros desafíos existentes en la región, como son las organizaciones criminales transnacionales, las cuales impiden la estabilidad de países centroamericanos, especialmente Honduras, Guatemala y El Salvador. Con todo, el documento solo dedica una página a Latinoamérica, en la línea de la tradicional mayor atención de Washington hacia las áreas del mundo que afectan más a sus intereses y seguridad.

Una oportunidad para el acercamiento de Estados Unidos a los países latinoamericanos será la Cumbre de las Américas, que se celebrará el próximo mes de marzo en Lima. Sin embargo, nada es predecible dada la actitud tan característica del mandatario, la cual deja un gran espacio abierto para posibles sorpresas.

[Graham Allison, Destined for War. Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap? Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Boston, 2017. 364 pages]

REVIEW / Emili J. Blasco [Spanish version]

This is what has been called the Thucydides Trap: the dilemma facing a hegemonic power and a rising one that threatens that hegemony. Is war inevitable? When Thucydides recounted the Peloponnesian War, he wrote about the inevitability for the dominant Sparta and the emerging Athens to think of armed confrontation as a means of settling the conflict.

The fact that these two Greek polis necessarily thought about war –and finally they waged it–, does not mean that they did not have other options. History has shown that there are other alternatives: when Wilhemine Germany threatened to overcome Britain's naval force, the attempt of sorpasso (accompanied by several circumstances) led to the First World War, but when Portugal was overtaken by Spain in overseas possessions in the sixteenth century, or when the United States replaced Britain as the world's leading power in the late nineteenth century the power transfer was peaceful.

Destined for War. Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap?, by Graham Allison, is a call to Washington and Beijing to do everything possible to avoid falling into the trap described by the Greek historian. In this book the founding dean of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government reviews several historical precedents. Harvard's Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, of which Allison is director, has researched on them in a program called precisely Thucydides's Trap.

This concept is defined by Allison as "the severe structural stress caused when a rising power threatens to upend a ruling one. In such condition, not just extraordinary, unexpected events, but even ordinary flashpoints of foreign affairs, can trigger large-scale conflict.”

|

The structural stress is produced by the clash of two deep sensibilities: the rising power syndrome ("a rising state's enhanced sense of itself, its interests, and its entitlement to recognition and respect"), and its mirror image, the ruling power syndrome ("the established power exhibiting an enlarged sense of fear and insecurity as it faces intimations of decline").

Along with those syndroms the two rival powers also experience a 'secutity dilemma': “A rising power may discount a ruling state's fear and insecurity because it 'knows' itself to be well-meaning. Meanwhile, its opponent misunderstands even positive initiatives as overly demanding, or even threatening.”

The use of military force

Allison starts from the fact that China is already putting itself on par with the United States as a world power. It has done so in terms of the volume of its economy (China has already overtaken the U.S. in Purchasing Power Parity) and with regard to some aspects of military force (a report by Rand Corporation predicted that in 2017 China would have an “advantage” or “approximate parity” in 6 of the 9 areas of conventional capability). The author's assumption is that China will soon be able to wrest from the United States the scepter of main superpower. In this situation, how will both countries react?

In the case of China, its thousand-year perspective will probably lead to a attitude of patience, provided there is at least some small progress in its purpose of increasing its global weight. Since 1949 China has only resorted to force in three of 33 territorial disputes. In those cases, the Chinese leaders waged the war –they were limited wars, conceived as a warning to their opponents– even though the enemy was equal or greater, urged by a situation of domestic unrest.

For Allison, “As long as developments in the South China Sea are generally moving in China's favor, it appears unlikely to use military force. But if trends in the correlation of forces should shift against it, particularly at a moment of domestic political instability, China would initiate a limited military conflict, even against a larger, more powerful state like the US.”

For its part, the United States can choose several strategies, according to Allison: accommodate to the new reality, undermine Chinese power (commercial war, fostering separatism of the provinces), negotiate a long peace, and redefine the relationship. The author does not give firm advice, but seems to suggest that Washington should move between the last two options.

He recalls how Britain understood that it could not compete with the United States in the Western Hemisphere, and how from there a collaboration between the two countries grew, as manifested in the First and Second World War. This should happen by accepting that the South China Sea is an area of Chinese influence. The United States should admit this, not out of mere condescension, but because it proceeds to a real clarification of its vital interests.

Despite its positive tone, Destined for War is one of the essays by the American establishment where the end of the American era and the passing the baton to China are most openly announced (it does not seem to glimpse a multipolar or bipolar world, but rather a primacy of the Asian country). It is also one of those assays that puts less accent –clearly less than it should– on the remaining strengths of the U.S. and the problems that can undermine the coronation of China.

[Graham Allison, Destined for War. Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap? Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Boston, 2017. 364 páginas]

RESEÑA / Emili J. Blasco [Versión en inglés]

Es lo que se ha llamado la trampa de Tucídides: el dilema al que se enfrentan una potencia hegemónica y otra en alza que amenaza esa hegemonía. ¿Es inevitable la guerra? Cuando Tucídides narró la guerra del Peloponeso, escribió sobre la inevitabilidad para la dominante Esparta y la emergente Atenas de pensar en la confrontación armada como medio para dirimir el conflicto.

El que esas dos polis griegas necesariamente pensaran en la guerra, y finalmente llegaran a ella, no quiere decir que no tuvieran otras opciones. La historia ha demostrado que las hay: cuando la Alemania guillermina amenazó con superar la fuerza naval de Gran Bretaña, el intento de sorpasso (acompañado de varias circunstancias) desembocó en la Primera Guerra Mundial, pero cuando Portugal se vio sobrepasada por España en posesiones ultramarinas en el siglo XVI, o cuando Estados Unidos sustituyó a Gran Bretaña como principal potencia mundial a finales del siglo XIX el traspaso fue pacífico.

La llamada a Washington y Pekín a hacer todo lo posible para no caer en la trampa descrita por el historiador griego la realiza Graham Allison en Destined for War. Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap? El decano fundador de la Kennedy School of Government de Harvard repasa en su libro diversos precedentes históricos. Sobre ellos ha investigado el Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs de esa misma Universidad, del que Allison es director, en un programa bautizado precisamente como Thucydides's Trap.

Este concepto es definido por Allison como “el fuerte estrés estructural causado cuando una potencia emergente amenaza con desbancar a una potencia reinante. En tal situación, no solo acontecimientos extraordinarios o inesperados, sino incluso focos ordinarios de tensión en asuntos internacionales pueden desencadenar conflictos a gran escala”.

|

Ese estrés estructural se produce por el choque de dos profundas sensibilidades: el síndrome de la potencia emergente (“la reforzada sensación que un estado emergente tiene de sí mismo, sus intereses y su derecho a reconocimiento y respeto”), y su imagen inversa, el síndrome de la potencia reinante (“la potencia establecida exhibe una crecida sensación de miedo e inseguridad a medida que enfrenta indicios de declive”).

Junto a los síndromes ambas potencias rivales experimentan también un dilema de seguridad: “una potencia en alza pude no tener en cuenta el miedo y la inseguridad de un estado dirigente porque sabe que ella misma es bienintencionada. Mientras tanto, su oponente malinterpreta incluso iniciativas positivas, tomándolas como excesivamente exigentes o incluso amenazantes”.

El uso de la fuerza militar

Allison parte del hecho de que China ya se está poniendo a la par de Estados Unidos como potencia. Lo ha hecho en cuanto al volumen de su economía (China ya ha sobrepasado a EE.UU. en Paridad del Poder Adquisitivo) y en relación a algunos aspectos de la fuerza militar (un informe de Rand Corporation predecía que en 2017 China tendría “ventaja” o “paridad aproximada” en 6 de las 9 áreas de capacidad convencional. La asunción del autor es que China estará en breve en condiciones de arrebatar a Estados Unidos el cetro de mayor superpotencia. Llegados ante esta situación, ¿cómo van a reaccionar ambos países?

En el caso de China, su perspectiva milenaria probablemente le llevará a una actitud de paciencia, siempre que haya algún pequeño progreso en su propósito de incrementar su peso específico mundial. Desde 1949 China solo ha recurrido a la fuerza en tres de 33 disputas territoriales. En esos casos, los dirigentes chinos plantearon la guerra –guerras limitadas, concebidas como aviso a sus contrincantes– a pesar de que el enemigo era igual o mayor, urgidos por una situación de domestic unrest.

Para Allison, “mientras los acontecimientos en el Mar del Sur de China generalmente se muevan en favor de China, parece improbable que esta use la fuerza militar. Pero las tendencias en la correlación de fuerza se giraran en su contra, particularmente en un momento de inestabilidad política interna, China iniciaría un conflicto militar limitado, contra un estado incluso mayor y más poderoso como Estados Unidos”.

Por su parte, Estados Unidos puede optar por varias estrategias, según Allison: adaptarse a la nueva realidad, minar el poder chino (guerra comercial, fomentar el separatismo de provincias), negociar un paz duradera y redefinir la relación. El autor no da un consejo firme, pero parece sugerir que Washington debiera moverse entre las dos últimas opciones.

Así, recuerda cómo Gran Bretaña comprendió que no podía rivalizar con Estados Unidos en el Hemisferio Occidental, y cómo a partir de ahí se creó una colaboración entre los dos países, puesta de manifiesto en la Primera y Segunda Guerra Mundial. Ello tendría que pasar por aceptar que el Mar del Sur de China es una área de influencia china. Y eso no por mera condescendencia, sino porque Estados Unidos procede a una clarificación real de sus intereses vitales.

A pesar de su tono positivo, Destined for War es uno de los ensayos del establishment estadounidense donde más abiertamente se anuncia el fin de la era americana y el paso de testigo a China (no parece vislumbrar un mundo multipolar o bipolar, sino más bien de primacía de la potencia asiática). También es uno de los que menos acento pone –menos, desde luego, del que debiera– en las fortalezas que mantiene Estados Unidos y los problemas que pueden minar la coronación de China.

Cyclical movements in the Latin American economy show close links to fluctuations in mineral pricing

The attention of public opinion on the price of commodities usually focuses on hydrocarbons, especially oil, because of the direct consequences on consumers. But although there are important oil producers in Latin America, minerals are a more transversal asset in the region's economy, especially in South America. This is shown by the largely parallel lines that follow the evolution of non-energy minerals and GDP growth, both in times of boom and of decline.

ARTICLE / Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa [Spanish version]

Mining activity is a fundamental sector for most of the Latin American economies. The sector has a huge weight on exports and the attraction of foreign direct investment making it one of the most important sources of international currencies. Against the general perception of the non-energetic mining activities as a mature industry, the sector has demonstrated its capability to be attractive for investment and able to produce jobs and wealth. Latin American mining is the destiny of 30% of world investment in the sector, which is waiting for a rising in prices. The effect of these price fluctuations have direct consequences on the economies of the continent, being some of them deeply dependant on the exploitation and sell of its natural resources. The main goal of this analysis is to articulate a convincing explanation of the impact of price fluctuation on non-energetic minerals on national GDPs.

Firstly, it is important to explain the chronological evolution of prices in the most exploited minerals of Latin America. The general tendency of commodity prices during the last two decades has been marked by a great volatility. The so called super cycle of commodities [1] produced between 2003 and 2013, with recoil during 2008 and 2009, coincides with the golden decade of Latin America. This situation was produced thanks to an unprecedented rising of global demand, mainly of the emerging countries leaded by China. In fact, the rising of China has transformed the trade pattern in the region which is today the main trade partner of a large number of countries.

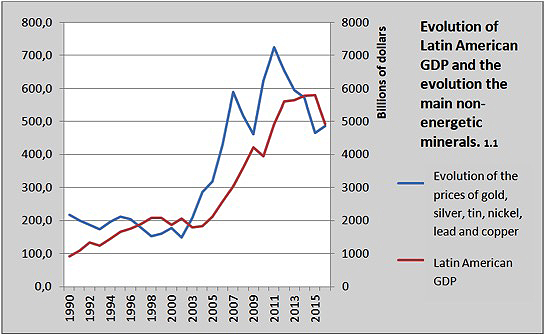

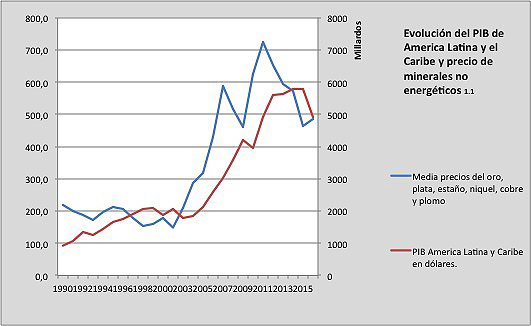

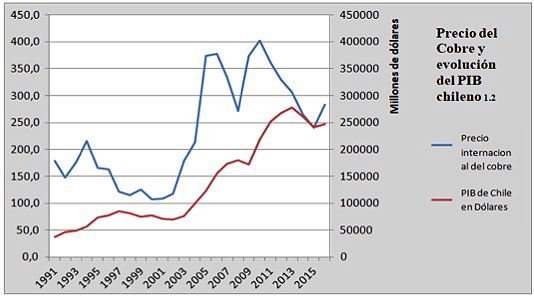

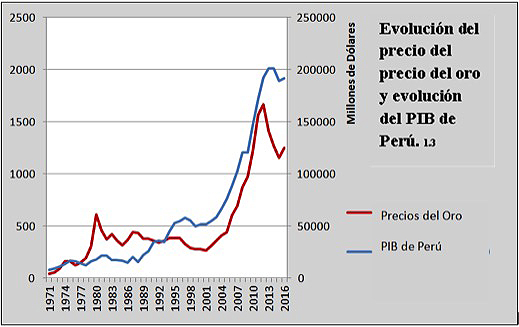

The mentioned evolution in commodity prices is similar to the one of the non-energetic minerals, which generally follows the tendencies of raw materials. As graph 1.1 shows, the region of Latin America and Caribbean has growth in correlation to the average evolution of the prices of gold, silver, tin, nickel, lead and copper. It is important to mention that this correlation in not an isolated one, and has to be analyzed in the context of a general rising in natural resource-based products such as hydrocarbons and agricultural goods.

|

[The graphics have been made from World Bank Data and national statistics of Peru and Chile] |

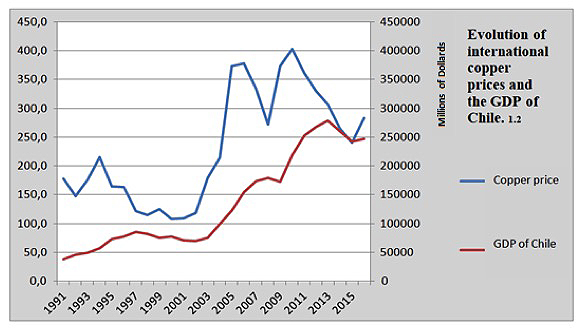

The Chilean case can be illustrative. The country has an economy particularly specialized on non-energetic minerals, outstanding copper as a core mineral for the country. Chile is the main producer of copper in the world and this mineral is around 50% of the national exports. The mining sector in Chile [2] represented the 20% of the country's GDP during the 2000’s, in 2017 it is only 9% of its economy. In graph 1.2 it is evident how the economic growth of Chile is directly linked with the different prices of copper. Even though it is one of the most complex and developed economies in the continent, with a tertiary sector [3] representing the 74% of its GDP, Chilean economy is still dependant and affected by copper prices and the situation of the mining industry.

|

|

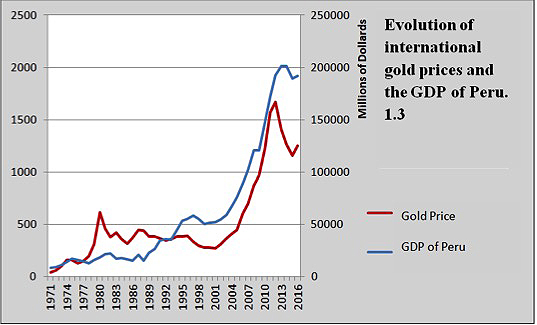

Another interesting case is the Peruvian one, a country whose exports are in a big proportion composed by non-energetic minerals. Gold is 18% and copper is 26% of all exports [4], reaching both more than 46% of them. Similarly to the case of Chile, 15% of its national GDP comes from the mining activities. Again, the correlation of mineral prices and economic growth is evident in graph 1.3, showing the huge dependence of these economies to the international prices of their exports.

|

|

This relationship is logical and has its answer in different realities. On the one hand, the quantitative value of natural resources on the Latin American economies, whose exports are mainly composed by mineral, agricultural or energetic commodities. On the other hand, the qualitative importance of the mining sector, which creates huge amounts of employs (up to 9% of the total in Chile), is the activity of some of the main companies in the region (among the 20 biggest companies in the Latin America, 5 are related to the mining activities), it is the main source of currencies and support public budgets by its particular fiscal regime. Equally, a big amount of national public debts are covered by those particular taxes, creating a situation of possible default in case of great fluctuations of prices. This menace brings back the memories of the debt crisis in the 80’s, something that it is now a reality in the case of Venezuela.

Must be taken into account that Latin American countries are not a unicity or a homogeneous reality, in general it is true that the region confronts a general challenge: be able of reduce the dependence of their economies to the exploitation and sell of its natural resources. An economic structure that is problematic because of its impact on the environment, a particular complex issue because of the resistance of indigenous groups to suffer from it. The nature of the employs created by this activity is sometimes disappointing, with low wages and bad labor conditions. Anyway, the industrial development of the region is still far from being sufficient and there is a rising awareness about the lack of economic structural reforms during the golden decade of 2003-2013 that could have changed the situation [5]. The profits derived from the mining sector are used to promote political interest or short-term goals with electoral sights.

This inefficient use of the public resources increases the vulnerability of the general welfare to the mentioned continuous shifts in prices. Even though perspectives about prices are optimistic and expect an imminent rise [6], they will not reach the levels of 2008, when they were at its historical maximum. This new context will demand a new approach to Latin American economies, which will not have access to the huge amount of money that they had during the past decade. Its economic growth will not come from an external favorable context, but from internal efforts to modernize and renovate its economic capability.

Los ciclos de la economía latinoamericana están muy ligados al precio de los minerales: los gráficos asombran

La atención de la opinión pública sobre el precio de las 'commodities' se centra muchas veces en los hidrocarburos, preferentemente el petróleo, por las consecuencias directas sobre los consumidores. Pero aunque en América Latina hay importantes productores de crudo, los minerales constituyen un activo más transversal en la economía de la región, sobre todo en Sudamérica. Así lo demuestran las líneas en buena medida paralelas que siguen la evolución de los minerales no energéticos y el crecimiento del PIB, tanto en momentos de 'boom' como de declive.

ARTÍCULO / Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa [Versión en inglés]

La explotación minera es una actividad fundamental para muchas economías latinoamericanas. El sector tiene un enorme peso en las exportaciones y llegada de inversión extranjera, convirtiéndolo en una de las principales fuentes de divisas. Frente a la percepción general de la minería no energética como una industria madura, el sector demuestra seguir siendo atractivo para inversionistas, y capaz de seguir generando empleo y riqueza. La minería latinoamericana recibe el 30% de las inversiones mundiales en el sector, el cual espera una recuperación en los precios. El impacto de estas fluctuaciones tiene consecuencias directas en las economías del continente, algunas de las cuales dependen enormemente de la explotación y venta de estos recursos. El objetivo de este análisis es el de articular una explicación convincente del grado en el que estas variaciones de precios afectan a los PIB nacionales.

En primer lugar, es importante detallar la evolución cronológica de los precios en los principales minerales explotados en Latinoamérica. La tendencia general de los precios de las materias primas durante las últimas dos décadas ha estado marcada por una enorme volatilidad. El denominado súper ciclo de las commodities [1] dado aproximadamente entre 2003 y 2013, con un retroceso entre 2008 y 2009, se produce al mismo tiempo que la denominada década dorada de América Latina. Esta situación se produjo por un alza sin precedentes de la demanda mundial, gracias a los países emergentes liderados por China, la cual ha transformado el comercio exterior en la región desplazando a EEUU como primer socio de buena parte de estos países.

La evolución en los precios ha seguido un patrón muy similar en la minería no energética, que por norma general sigue las tendencias en precios del resto de las materias primas. Cómo podemos ver en el gráfico 1.1, la región de América Latina y Caribe ha tenido un crecimiento económico muy similar a la evolución promedio de los precios del oro, la plata, el estaño, el níquel, el plomo y el cobre. Es importante mencionar que la relación entre estas dos variables no es aislada, y debe analizarse en el mencionado contexto de un alza general de los precios de otras materias primas de vital importancia para la región cómo los hidrocarburos o los productos agrícolas.

|

[Los gráficos está confeccionados a partir de World Bank Data y estadísticas nacionales de Perú y Chile] |

El caso de Chile puede ser de enorme utilidad. Chile cuenta con una economía particularmente especializada en la minería no energética, destacando la explotación del cobre, actividad en la cual es líder mundial y que supone el 50% de sus exportaciones. El sector minero en Chile [2] llegó a ser casi el 20% del PIB a mediados de la década del 2000; en 2017 ha supuesto en torno a un 9%. En el gráfico 1.2 vemos como el precio del cobre marca la senda económica del país, coincidiendo las mayores épocas de crecimiento económico chileno con el incremento de los precios del cobre. A pesar de tratarse de una de las economías más desarrolladas de la región [3], con un peso del sector servicios en el PIB del 74%, el país sigue condicionado por la coyuntura de su sector primario y concretamente la minería.

|

|

Otro caso interesante es el de Perú, un país cuyas exportaciones cuentan con una buena participación de minerales no energéticos [4], alcanzando en el caso del oro (18%) y el cobre (26%) conjuntamente el 46% de las mismas. De forma similar a Chile la participación de la minería en la economía es del 15% del PIB. De nuevo, podemos apreciar la correlación existente entre los precios de ciertos minerales no energéticos estratégicos y el crecimiento económico.

|

|

Esta relación es lógica y responde a varias realidades. Por un lado, el gran valor cuantitativo de las materias primas en las economías latinoamericanas, que concentran sus exportaciones en productos agrícolas, minerales y energéticos. Por otro lado, su importancia cualitativa ya que el sector genera grandes cantidades de empleo (hasta un 9% en Chile), es el objeto de muchas de las principales empresas de la región (5 de las 20 más grandes de Latinoamérica se dedican a la extracción), es la principal fuente de divisas y deja enormes beneficios para las arcas de los Estados, pues se rigen bajo un sistema impositivo particular más gravoso. De igual modo, buena parte del pago de deuda externa es sufragada por medio de estos ingresos, la inestabilidad en los precios podría traer de nuevo los fantasmas de la crisis de deuda de los ochenta, algo que ya es una realidad en el caso de Venezuela.

Si bien los países de América Latina no pueden ser analizados como una unidad heterogénea, en líneas generales la región sí que afronta un reto común: el ser capaz de reducir la dependencia de sus economías a la explotación y exportación de las materias primas. Una actividad que cuenta con elementos problemáticos como su impacto en el medio ambiente, un asunto particularmente complejo en la región por la reticencia de los grupos indígenas, o la calidad y estabilidad del empleo que generan. En cualquier caso, el desarrollo industrial de la región sigue siendo deficiente y cada vez hay más voces que alertan de que la década dorada de 2003-2013 no fue aprovechada para realizar los cambios estructurales necesarios para mitigar esta situación [5].

La existencia de complejas realidades socio-políticas en Latinoamérica ha llevado muchas veces a emplear los beneficios derivados de la extracción en políticas cortoplacista y electorales, una lacra que aumenta la exposición del bienestar social a los vaivenes del sector minero y energético. Si bien las predicciones sobre el precio de las materias primas apuntan a una inminente recuperación [6], no se prevé una situación similar a la dada en torno a 2008 cuando los precios alcanzaron máximos históricos. Esta nueva coyuntura exigirá el máximo a las economías latinoamericanas, que no contarán con una situación de la economía internacional tan favorable.

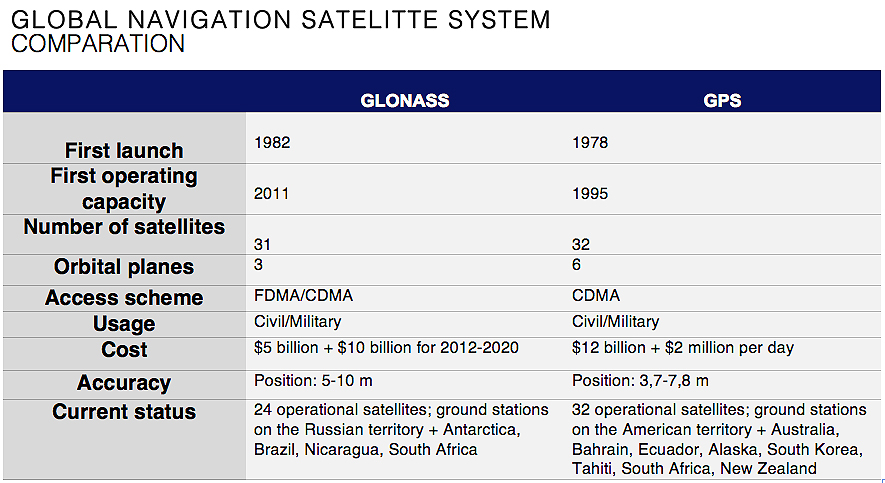

The Russian positioning system GLONASS has placed ground stations in Brazil and Nicaragua; the different accessibility of them to nationals gives rise to conjectures

At a time when Russia has declared its interest in having new military facilities in the Caribbean, the opening of a Russian station in the Managua area has raised some suspicions. Roscosmos, the Russian space agency, has opened four stations in Brazil, managed with transparency and easy access; instead, the one that has built in Nicaragua is surrounded by secrecy. What little is known about the Nicaraguan station, strangely greater than the others, contrasts with the openly that data can be collected on the Brazilians.

ARTICLE / Jakub Hodek [Spanish version]

We know that information is power. The more information you have and manage, the more power you enjoy. This approach must be taken into account when examining the ground stations that serve to support the Russian satellite navigation system and its construction in relative proximity to the United States. Of course we are no longer in the Cold War period, but some of the traumas of those old times may help us to better understand the cautious position of the United States and the importance that Russia sees in having its facilities in Brazil and especially in Nicaragua.

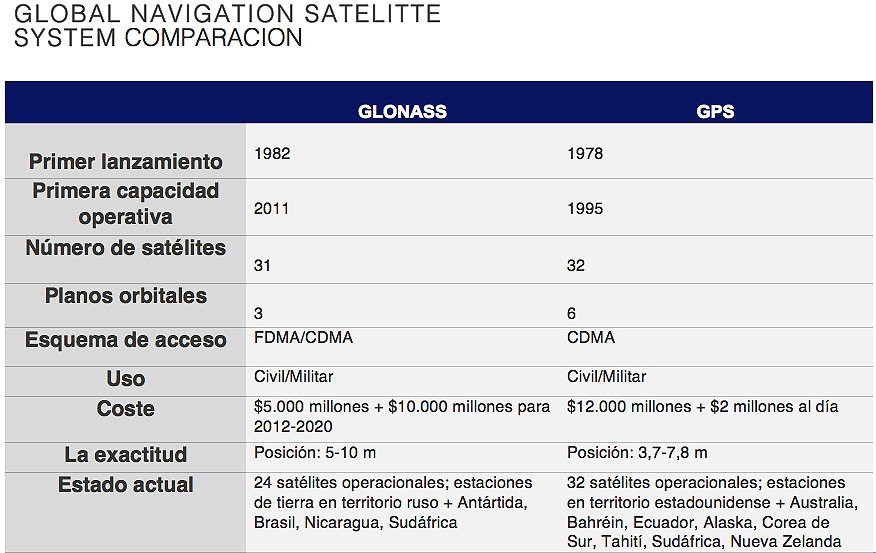

That historical background of the Cold War is at the origin of the two largest navigation systems we use today. The United States launched the Global Positioning System (GPS) project in the year 1973, and possibly in response, the Soviet Union presented its own positioning System (GLONASS) three years later. [1] It has been almost 45 years, and these two systems no longer serve Russians and Americans to try to get information on each other, but are collaborating and thus offering a more accurate and fast navigation system for consumers who buy a Smartphone or other electronic device. [2]

However, in order to achieve global coverage, both systems need not only satellites, but also ground stations strategically distributed around the world. For that purpose, the Russian Federal Space Agency, Roscosmos has erected stations for the GLONASS system in Russia, Antarctica and South Africa, as well as in the Western Hemisphere: it has four stations in Brazil and since April 2017 has one in Nicaragua, which by secrecy around its purpose has caused mistrust and suspicion in the United States [3] (USA, for its part, has ground stations for GPS in its territory and Australia, Argentina, United Kingdom, Bahrain, Ecuador, South Korea, Tahiti, South Africa and New Zealand).

The Russian Global Satellite Navigation System (Globalnaya Navigatsionnaya Sputnikovaya sistema or GLONASS) is a positioning system operated by the Russian Aerospace Defence Forces. It consists of 28 satellites, allowing real-time positioning and speed data for the surface, sea and airborne objects around the world. [4] In principle GLONASS does not transmit any personally identifiable information; in fact, user devices only receive signals from satellites, without transmitting anything back. However, it was originally developed with military applications in mind and carries encrypted signals that are supposed to provide higher resolutions to authorized military users (same as the US GPS). [5]

|

In Brazil, there are four Earth stations that are used to track signals from the GLONASS constellation. These stations serve as correction points in the Western hemisphere and help significantly improve the accuracy of navigational signals. Russia is in close and transparent collaboration with the Brazilian Space Agency (AEB), promoting research and development of the aerospace sector of this South American country. In 2013 the first station was installed, located on the campus of the University of Brasilia, which was also the first Russian station of that type abroad. It followed another station in the same place in 2014, and later, in 2016, a third was put in the Federal Institute of Sciences of the education and technology of Pernambuco, in Recife. The Russian Federal Space agency Roscosmos built its fourth Brazilian station on the territory of the Federal University of Santa Maria, in Rio Grande del Sur. In addition to fulfilling its main purpose of increasing accuracy and improving the performance of GLONASS, the facilities can be used by Brazilian scientists to carry out other types of scientific research. [6]

The level of transparency that surrounded the construction and then has prevailed in the management of the stations in Brazil is definitely not the same as the one applied in Managua, the capital of Nicaragua. There are several information that create doubts regarding the true use of the station. For starters, there is no information about the cost of the facilities or about the specialization of the staff. The fact that the station has been put at a short distance from the U.S. Embassy has given rise to conjecture about its use for phone-tapping and spying.

In addition, the vague replies from the representatives of Nicaragua and Roscosmos about the use of the station, have not managed to transmit confidence in the project. It is a "strategic project" for both Nicaragua and Russia, concluded Laureano Ortega, the son of the Nicaraguan president. Both countries claim to have very fluid and close cooperation in many areas, such as in health and development projects. However, none of those collaborations have materialized with such speed and dedication as this particular project. [7]

Given Russia's larger military presence in Nicaragua, empowered by the agreement that facilitates the mooring of Russian warships in Nicaragua announced by Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu during his visit to the Central American country in February 2015, and specified also in the donation of 50 T-72B1 Russian tanks in 2016 and the increased movement of the Russian military personnel, it can be concluded that Russia clearly sees strategic importance in its presence in Nicaragua. [8] [9] This is all observed with suspicion from America. The head of South American Command, Kirt Tidd, warned in April that "the Russians are moving forward a disturbing attitude" in Nicaragua, which "impacts the stability of the region."

Without a doubt, when world powers like Russia or the United States act outside their territory, they are always guided by a combination of motivations. Strategic positioning is essential in the game of world politics. For this very reason, the aid that a country receives or the collaboration it can establish with a great power is often subject to political conditionality.

In this case, it is difficult to know for sure what is the purpose of the station in Nicaragua or even those of Brazil. At first glance, the objective seems neutral – offering higher quality navigation system and providing a different option to GPS –, but given the new importance that Russia is granting to its geopolitical capabilities, there is the possibility of more strategic use.

The thaw has caused the release of icebergs that may be a risk to navigation, but in Antarctica the geopolitics is partially frozen

The increase of the temperatures is opening the Arctic to the commercial routes and to the dispute between countries for the future control of the riches of its subsoil. In Antarctica, with lower temperatures and a slower thaw, what is under the white mantle is not an ocean, but a continent away from the navigation lines and the direct interests of the great powers. There are reasons for the main international actors to prefer to continue leaving in the fridge all claims about the South Pole.

ARTICLE / Alona Sainetska [Spanish version]

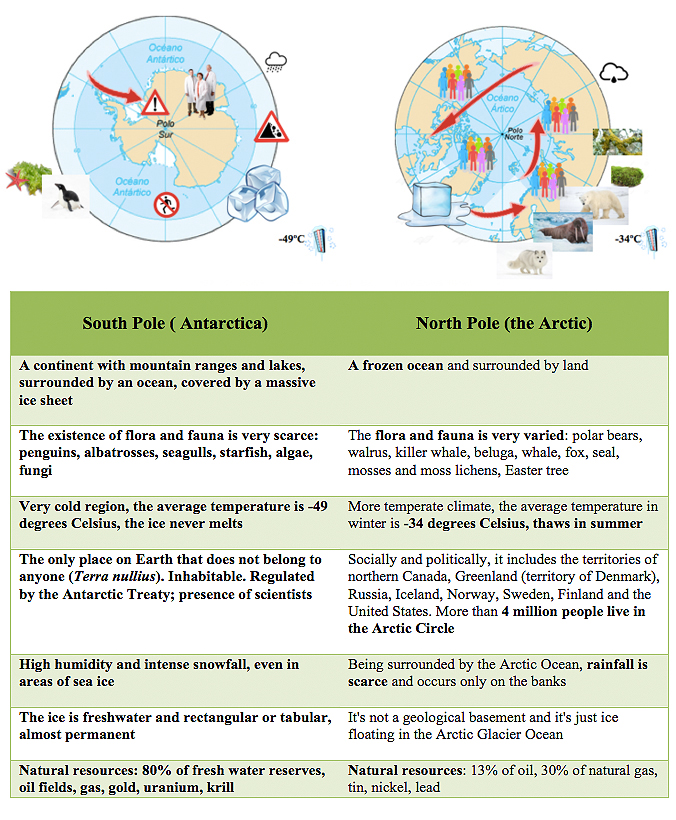

Antarctica is a continent with mountain ranges and lakes, surrounded by an ocean and with a total area of 14 million square kilometers. It is often compared to the Arctic which is, instead, an icy sea surrounded by land. In the north of the Arctic Circle live about 4 million people. In contrast, the Antarctica, with its average of -49° C of temperature, is absolutely uninhabitable and is considered today as a natural sanctuary that attracts the attention of numerous countries from all over the world.

Even though the South Pole does not present, at a first glimpse, any important elements for a conflict in the global, international system, the sovereignty of its territory has never been exempt from disputes and territorial claims by countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Norway, France, Argentina and Chile. Although lately they were left in abeyance, the claims of those countries do not interfere with others, except in the case of Argentina and Chile, whose claims were made on the parts of the land that have already been requested totally or partially by England.

In this context there has occurred a transcendental coincidence of interests among the aforementioned countries which also spread to the non-claiming superpowers, as was the case of the United States and the USSR. Both showed little desire to convert the continent and the maritime space into an object of political-military clashes. This fact facilitated a lot the negotiations about the future legal status that would have "the frozen continent".

The first attempt to establish a special legal regime for Antarctica was the initiative of the United States, in 1948. However, this idea failed while clashing with the opposition of countries that wished to expand their sovereignty to the territories of Antarctica. Only two years later, when the USSR announced that it would not accept any agreement on Antarctica in which it was not represented, could the continent arouse interest of the great powers once again.

Facing the need of reaching a consensus and as a result of the enormous efforts of the world scientific community, a climate of cooperation and international dialogue on Antarctica was born. This allowed free access of scientists of any nationality to the continent, as well as the exchange of the results of their investigations.

This new context led to the signature of the Treaty on Antarctica (ATS), on December 1, 1959 , which entered into force on June 23, 1961. Any possible modification, by majority, was postponed until a conference scheduled for 30 years after its enforcement. However, when 1991 arrived, there were no changes applied and, what is even more, the safeguards were added.

In the AT, the member-countries committed themselves to recognize a special legal regime of Antarctica, giving it a status of "terra nullius". In addition, there was established a demilitarization of the Antarctic continent, which reserved the frozen space exclusively for peaceful purposes and prohibited the foundation of military bases.

On the other hand, it proclaimed the freezing of all claims of territorial sovereignty over Antarctica, not allowing either making new claims or expanding those previously made during the period of validity of the treaty.

In the same way, there was originated a right to appoint observers in order to ensure fulfillment of the objectives of the treaty and, additionally, there were organized some periodic meetings for both the original signatory states and those being assigned a consultative function for carrying out important scientific missions in Antarctica.

Scientific and economic potential

In 1991, there were some additional efforts made in the conservation of the frozen giant. In order to respond to issues such as climate change and the need to protect the special ecosystem that the continent represented, the so-called "complementary" protocol to the AT on environmental protection was signed in Madrid. The requisite for its entry into force was the obligation to be ratified by all the Antarctic Treaty consultative members.

It put under prohibition any exploitation of mineral resources, except those carried for scientific purposes. This restriction could only be lifted by unanimous agreement and kept the continent away from possible plunder of its great natural resources. Antarctica thus became a unique place in the world where the coexistence between man and nature could be possible and long-lasting.

However, the last decades supposed many strategic changes that have caused serious doubts and concerns regarding the effectiveness of the AT. Antarctica’s scientific and economic potential, together with its enormous biodiversity and richness in natural resources, have greatly increased its importance. The greater interaction and interdependence of the numerous national, international and transnational actors that form the world community has also multiplied the desire to influence and participate, in different ways, in the pursuit of particular interests in this area of the world.

Thus, not only there are projects aimed to guarantee environmental conditions, such as discussion on the creation of a large area of natural preservation in the Ross Sea, but also some controversial initiatives in order to take advantage of Antarctic resources. One example could be a recent suggestion of the Arab Emirates to tow icebergs from the masses of Antarctic ice towards the Middle East, in order to combat drought and meet the needs of its population (Antarctica contains 80% of the planet's freshwater reserves).

These icebergs, on the other side, can present a tremendous threat to navigation and commerce, especially in the case of the large ones, such as Larsen C, which is every day increasingly closer to a collapse. The consequences may be tragic - a huge iceberg of 5,800 square kilometres left adrift.

|

Countries with different weight

Although, due to the disadvantages resulting from the remoteness of the continent and its harsh and unfavourable conditions, a possible exploitation of Antarctica is not foreseen for the short run and remains now more hypothetical rather than real, there is still a risk of future deployment of economic activity in the Antarctic region worldwide.

The latter will depend on international alignments that may arise.

The alignments in relation to the Antarctica follow the administration structure imposed by the Treaty, which includes three categories of members:

-

The original signatories (Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South African Republic, Soviet Union, Great Britain and the United States) participating in a full right in the consultative meetings of the AT where decisions are made.

-

Those States that wish to join and, having developed activities important scientists, obtain the consent to participate in the Consultative meetings (for example: Poland, Germany, India, Brazil, China and Uruguay).

-

Finally, the States that adhere, but, because of not carrying out a significant scientific activity, cannot participate in decision-making (Czechoslovakia, Cuba, Hungary, Bulgaria, Peru, Italy, New Guinea, Spain, Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark, Romania and Finland).

A similar situation of collision of interests among the international actors is evident at the opposite pole of the Earth, the Arctic. Its climatic conditions have much warmer temperatures that allow the melting of its sensitive layer of ice. So, the thaw caused by the global warming makes the Arctic's energy wealth more and more accessible (it is estimated that it harbours 13% of the oil and 30% of the natural gas that remains in the planet). As a direct consequence of that, the struggle for gaining rights to exploit it is being intensified between countries such as, Denmark, Canada, the United States, Norway and Russia.

On the other hand there is China, for which the thawing has a lot of positive consequences, such as the opening of new inter-oceanic navigation routes between northern Europe and much shorter Shanghai, or easier access to mining areas like Greenland.

In light of the above considerations (the abundance of essential minerals in technology, the opening of new routes or maritime transport and the fact that the lands located in the Arctic Circle are habitable, along with benevolent conditions and easier access), it is very likely that the Arctic may be integrated into the world economic structure much sooner than Antarctica.

El sistema de posicionamiento ruso GLONASS ha colocado estaciones de tierra en Brasil y Nicaragua; las brasileñas son accesibles, pero la nicaragüense da pie a conjeturas

En un momento en que Rusia ha declarado su interés en tener de nuevo instalaciones militares en el Caribe, la apertura de una estación rusa en el área de Managua ha levantado algunas sospechas. Roscosmos, la agencia espacial rusa, ha abierto cuatro estaciones en Brasil, gestionadas con transparencia y fácil acceso; en cambio, la que ha construido en Nicaragua se ve rodeada de secretismo. Lo poco que se sabe sobre la estación nicaragüense, extrañamente mayor que las otras, contrasta con lo abiertamente que pueden recabarse datos sobre las brasileñas.

ARTÍCULO / Jakub Hodek [Versión en inglés]

Ya se sabe que la información es poder. Cuanta más información se tiene y administra, de más poder se goza. Hay que tener este planteamiento a la hora de examinar las instalaciones de estaciones que sirven para apoyar el sistema de navegación por satélites ruso y su construcción en proximidad relativa a Estados Unidos. Por supuesto que ya no estamos en el periodo de Guerra Fría, pero algunas traumas de aquellos viejos tiempos quizás nos pueden servir para entender mejor la posición cautelosa de Estados Unidos y la importancia que ve Rusia en tener sus instalaciones en Brasil y especialmente en Nicaragua.

Ese trasfondo histórico de la Guerra Fría está en el origen de los dos sistemas de navegación más grandes que utilizamos hoy en día. Estados Unidos lanzó el proyecto de Sistema de Posicionamiento Global (GPS) en el año 1973, y posiblemente como respuesta, la Unión Soviética presentó su propio sistema de posicionamiento (GLONASS) tres años después. [1] Han pasado casi 45 años, y estos dos sistemas ya no sirven para que rusos y estadounidenses intenten obtener información sobre el bando contrario, sino que están colaborando y así ofreciendo un sistema de navegación más preciso y rápido para los consumidores que compran un smartphone u otro aparato electrónico. [2]

Sin embargo, para conseguir una cobertura mundial ambos sistemas necesitan no solo satélites, sino también estaciones de tierra repartidas estratégicamente por el mundo. Con ese propósito, Agencia Espacial Federal Rusa Roscosmos ha erigido estaciones para el sistema GLONASS en Rusia, en la Antártida y en Sudáfrica, así como en el hemisferio occidental: ya tiene cuatro estaciones en Brasil y desde el abril de 2017 cuenta con una en Nicaragua, que por el secretismo en torno a su función ha causado desconfianza y sospecha en Estados Unidos [3] (EE.UU., por su parte, tiene estaciones de tierra para GPS en su territorio y en Australia, Argentina, Reino Unido, Bahréin, Ecuador, Corea del Sur, Tahití, Sudáfrica y Nueva Zelanda).

El Sistema Global de Navegación por Satélite ruso (Globalnaya Navigatsionnaya Sputnikovaya Sistema o GLONASS) es un sistema de posicionamiento operado por las fuerzas de Defensa aeroespaciales rusas. Consiste en 28 satélites, permitiendo posicionamiento en tiempo real y speed data para la superficie, el mar y los objetos aerotransportados alrededor del mundo. [4] En principio GLONASS no transmite ninguna información de identificación personal; de hecho, los dispositivos de usuarios solo reciben señales de los satélites, sin transmitir nada de vuelta. Sin embargo, fue desarrollado originalmente con las aplicaciones militares en mente y lleva señales cifradas que se supone que proporcionan resoluciones más altas a los usuarios militares autorizados (lo mismo el GPS estadounidense). [5]

En Brasil, hay cuatro estaciones de tierra que se utilizan para rastrear señales de la constelación GLONASS. Estas estaciones sirven como puntos de corrección en el hemisferio occidental y ayudan a mejorar significativamente la precisión de las señales de navegación. Rusia está en estrecha y transparente colaboración con la agencia espacial brasileña (AEB), promoviendo la investigación y el desarrollo del sector aeroespacial del país sudamericano.

|

En 2013 se instaló la primera estación, ubicada en el campus de la Universidad de Brasilia, que además era la primera estación rusa de ese tipo en el extranjero. Siguió otra estación en el mismo lugar en 2014, y posteriormente, en 2016, se puso una tercera en el Instituto Federal de Ciencias de la Educación y Tecnología de Pernambuco, en Recife. La Agencia Espacial Federal Rusa Roscosmos construyó su cuarta estación brasileña en el territorio de la Universidad Federal de Santa María, en Río Grande del Sur. Además de cumplir su propósito principal de aumentar la exactitud y mejorar el rendimiento de GLONASS, las instalaciones pueden ser usadas por los científicos brasileños para llevar a cabo otros tipos de investigación científica. [6]

El nivel de transparencia que rodeó la construcción y luego ha imperado en la gestión de las estaciones en Brasil definitivamente no es el mismo aplicado a la abierta en Managua, la capital de Nicaragua. Hay varias informaciones que siembran dudas en relación al verdadero uso de la estación. Para empezar, no hay información sobre el costo de las instalaciones o sobre la especialización del personal. El hecho de que se haya puesto a corta distancia de la Embajada de Estados Unidos ha dado pie a conjeturas sobre su uso para escuchas y espionaje.

Además, las respuestas vagas de los representantes de Nicaragua y de Roscosmos acerca del uso de la estación, no han conseguido transmitir confianza sobre el proyecto. Es un “proyecto estratégico” tanto para Nicaragua como para Rusia, concluyó Laureano Ortega, el hijo del presidente nicaragüense. Ambos países aseguran tener una cooperación muy fluida y estrecha en muchas esferas, como en proyectos relacionados con la salud y el desarrollo, sin embargo ninguno de ellos se han materializado con tal velocidad y dedicación. [7]

Dada la mayor presencia militar de Rusia en Nicaragua, facultada por el acuerdo que facilita el atraque de buques de guerra rusos en Nicaragua anunciado por el Ministro ruso de Defensa Serguei Shoigu durante su visita al país centroamericano en febrero de 2015, y concretada también en la donación de 50 T-72B1 tanques rusos en 2016 y el movimiento creciente del personal militar ruso, se puede concluir que Rusia claramente ve importancia estratégica en su presencia en Nicaragua. [8] [9] Todo esto es vito con recelo desde EE.UU. El jefe del Comando Sur estadounidense, Kirt Tidd, advirtió en abril que “los rusos están llevando adelante una actitud inquietante” en Nicaragua, lo que “impacta en la estabilidad de la región”.

Sin duda que cuando potencias mundiales como Rusia o Estados Unidos actúan fuera de su territorio, lo hacen siempre guiados por una combinación de motivaciones. Los movimientos estratégicos son esenciales en el juego de la política mundial. Por esta misma razón, la ayuda que recibe un país o la colaboración que puede establecer con una gran potencia muchas veces está sujeta a una condicionalidad política. En este caso, es difícil saber con seguridad cuál es exactamente el objetivo de la estación en Nicaragua o incluso las de Brasil. A primera vista, el objetivo parece neutro –ofrecer calidad más alta de sistema de navegación y proveer diferente opción a la de GPS–, pero dado el nuevo valor que Rusia está concediendo a sus capacidades geopolíticas, existe la posibilidad de un uso más estratégico.