In the image

Damaged International Convention Centre in the capital of Nepal after Gen Z Protest, September 2025 [Bijay Chaurasia]

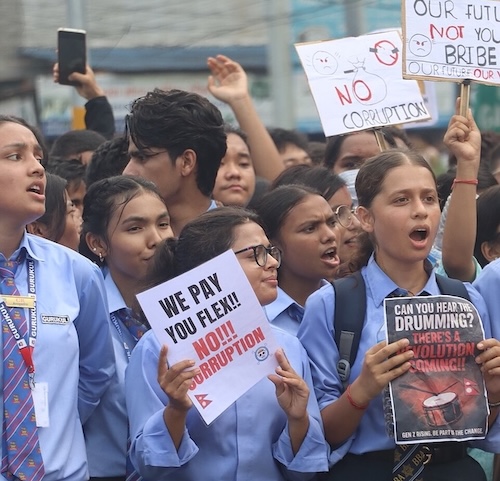

On September 9, 2025, the Nepalese Parliament was set on fire by young protesters, as part of the most violent unrest the country has faced in several years. During the protests, which began on September 8 and lasted 3 days, at least 72 people were killed by security forces, and official buildings, residences of political leaders and luxury hotels were targeted by arson, vandalism and looting. This ‘Gen Z Revolution’ was a direct consequence of the social media blockage by the Nepali Government, whose prime minister resigned after 48 hours of the violent revolt. However, Nepal is not the only country which has faced this political awakening. Other Asian countries such as Indonesia, Philippines and Bangladesh have also experienced these uprisings, which has aroused the idea that the ‘Gen Z’ has awakened.

It is essential to analyze the key events that unfolded in early September in Nepal: the youth unrest had already begun by the day before the parliament was set ablaze, on September 8, after the announcement by the government of a social media ban of dozens of platforms. The reason given by the government for this ban was that these platforms did not comply with a series of registration requirements, which consisted of obtaining a license and appointing a representative in charge of addressing grievances. Among those platforms were several widely used social networks, including Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram and LinkedIn. Officials at the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology claimed it was their only option after several formal appeals, all followed by the refusal of those platforms to accept the new regulations. The ban was implemented on September 4, and led to many critics by the Nepali population, regarding the dubious intentions of the Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli to impose government control on speech after years of failure. The young protesters gathered in Kathmandu’s Maitighar Mandala and spread to other urban centers. The use of lethal force by the police to control the situation caused the death of 19 people, and others were injured.

On September 9, increased violence led to the collapse of the government, and Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli resigned. The parliament, Supreme Court, political party offices and leaders’ houses were set on fire. The Army took control of security in the capital: a curfew was established among all the country and warned of ‘mob justice’. The deaths rose to 25, as well as 600 injured.

Finally, on September 10, the country found itself in a situation of political vacuum: with no government and the army in charge of national security. The same evening, an online vote through a Discord channel (a communication space within Discord, an online platform used for online messaging and interaction), ‘Youths Against Corruption’, took place, with Sushila Karki, former Chief Justice, emerging as the winner and interim Prime Minister.

A deep-seated frustration

The events that occurred in Nepal during these days clearly reflect a deep-seated frustration and discontent among the young Nepali population, which had been building long before the social media blockade was issued. It was evident that the protesters wanted change. Frustration and anger against the government and its communist leader, K.P. Sharma Oli, coalesced around a range of issues.

First, and most important, the population had been suffering decades of systemic corruption. Indeed, one of the main demands of the activists, apart from lifting the social media ban, was the establishment of an independent anti-corruption body. Nepal ranks 107th out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index 2024, and has also been placed in the ‘grey list’ of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). Corruption in Nepal has permeated everyday life, reinforced by its political and economic context: highly regulated economies which create monopolies, restriction of civil liberties, manipulation of national laws and ineffective law enforcement institutions. This causes government officials to normalize corruption, as it provides them with great benefits in exchange for little or no consequences.

The issue of the ‘Nepo-Kids’ was another source of frustration that concerned the participants of the uprising. This name designates individuals who did not come of established business families, nor did they inherit substantial wealth, which raised questions among the population about the origins of their privileged situation, with a luxurious life and foreign education. Weeks before the protests, photographs showing the wealthy lifestyles of these ‘Nepo-Kids’ went viral across social media. They are young people who have benefited from their families’ privileged position; children of Nepal’s political elite, who evidence the corruption and inequality that is present in Nepal: while 20,3% of population live below the National Poverty Line (2022), this privileged elite enjoy a luxurious life, which generated resentment among the Nepali population.

Political instability has been another major issue that led to the violent revolts. Since the monarchy was abolished in 2008, Nepal has experienced 14 different governments, all of which failed to remain in power for a full five-year term. This, as well as the recycling of the same political figures over the years, has contributed to the spread of frustration and distrust among the Nepali population, as they have perceived that the political change is superficial, and the same political elites that dominate power do not really represent the Nepali’s interests, but serve their own desire of power, wealth and privilege. Moreover, the absence of a consistent parliamentary opposition has led to a weak system of checks and balances: politics in Nepal is guided by self-interest, which is evidenced by the apparent lack of dominance of any of the three main ideologies in the Parliament (the Nepali Congress, Unified Marxist–Leninist and the Communist Party of Nepal), as all of the three parties cooperate with each other with the purpose of dividing the benefits of political power.

Finally, the lack of job opportunities among the population has also been a significant source of frustration among the young Nepalis. With a youth unemployment rate of 20.8% (2024), many people have tried to find new opportunities abroad, which is why around one-third of Nepal’s gross domestic product is generated through remittance inflows. Nepal has failed to provide qualified jobs for the high number of young, educated people. There is a considerable imbalance between the educational system and the skills demanded by the market (80% of the employment in the country is in the informal sector). This has led to mass frustration and migration to find new opportunities, mostly to Gulf countries.

Nevertheless, Nepal is not the only country to have experienced a youth-led uprising. Several ‘Gen-Z’ movements have emerged across different countries in Asia, and it is interesting to analyze the common patterns among them.