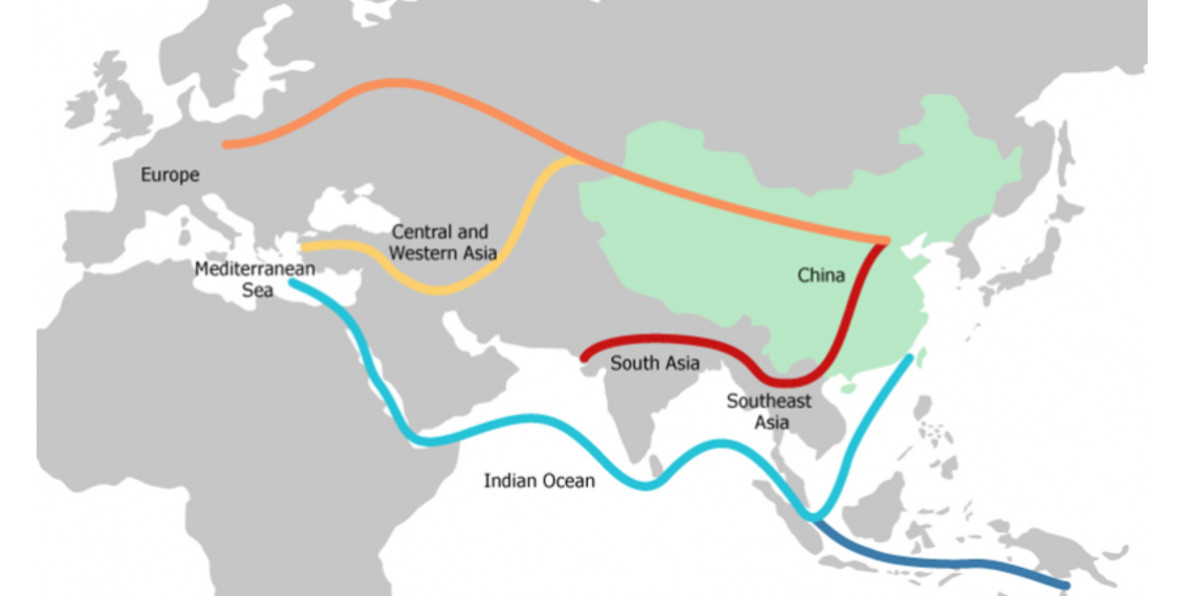

In the image

Simplified map of the ‘belts and roads’ that make up the Chinese initiative [United Nations]

Introduction

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), sometimes referred to as the “New Silk Road” or the “One Belt, One Road” Initiative is a global investment and infrastructure development project led by China. Launched in 2013 by President Xi Jinping during a state visit to Kazakhstan, BRI aims to model the original Silk Road which connected mainland imperial China to ancient Europe through a network of land-based trade routes. The Silk Road was the first glimpse at primitive globalization, connecting eastern and western societies through commerce; stimulating cultural connectivity and promoting economic prosperity.

Xi Jinping's “New Silk Road” is projected to include a Maritime Silk Road, a Digital Silk Road, a Polar Silk Road and, to date, six economic corridors: the New Eurasian Land Bridge, China-Central Asia-West Asia Corridor, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the Bangladesh-China-Myanmar Corridor, the China-Mongolia-Russia Corridor, and the China-Indochina Peninsula Corridor. As of today, over 150 countries have signed Memorandums of Understanding with the Chinese government to join Belt and Road.

Officially, China aims to encourage economic cooperation and connectivity between Asia, Europe, Africa and Latin America. Its main objective is to enhance global trade linkages, upgrade already existing markets in underdeveloped regions, improve basic living standards and establish itself as the administrator of world supply chains. Unofficially, it is speculated that BRI also has a hidden political agenda. In 2017, Indian geostrategist Brahma Chellaney devised the “Debt Trap Diplomacy” concept which stated that China is fulfilling its political ambitions by granting massive loans to underdeveloped countries (disguised as BRI investment lending) and then leasing or acquiring their assets when they fail to repay the loan in full. As a result, some international analysts argue that China is using BRI as a “trojan horse” to expand its sphere of influence and cement itself as a hegemonic global power.

The problem with this conclusion lies in the fact that most countries hedge between the US and China. Hedging is the practice by which small and oftentimes underdeveloped states balance their alliances between two great powers to “minimize risks and maximize benefits.” It grants smaller states a “fail-safe” in case one of the two powers becomes unreliable. For this particular case, BRI investment trends throughout the Asian continent (composed of Southeast Asia, East Asia, Central Asia and South Asia) between 2013 and 2022 will be used to analyze the influence that hedging has on the development of Belt and Road over the short and long term.

The objective of this paper is to analyze whether the Belt and Road Initiative is a way for China to achieve a larger political objective. And if so, what is it that it is trying to achieve? What challenges does hedging pose to the said objective? And why is it pushing such an agenda forward? This paper seeks to examine these questions through case studies of subregions within the Asian continent.

Largest investment: Southeast Asia

China is located in a strategic geographic position at the center of the Asian continent. It's reasonable to assume that it would prioritize engagement in a region that is geographically closer and culturally linked to it before venturing outwards. This is evidenced by the fact that in its totality the Asian continent witnessed the highest amounts of investment lending and infrastructure development of the entire project since 2013 (with a notable exception in 2016-2018 and 2022, which witnessed higher amounts of engagement in the Middle East).

Southeast Asia is composed of Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, Singapore and the Philippines. Mainland China shares an indisputable cultural connection to Southeast Asia as a result of massive migration movements towards Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Such collective consciousness between the Chinese and Southeast Asians opens the floor for safe and predictable investment trends which is highly attractive to Chinese companies willing to contribute to the expansion of BRI while still remaining risk averse. It becomes clear that Southeast Asia will become a focal point for investment and infrastructure development given that it provides both the Chinese government and private investors with safer and more reliable supply chains than do other regions struck by poverty and instability such as Africa and Latin America. At the same time, the geographic location of Southeast Asia both right at China's backyard and at the shores of the South China Sea makes the region incredibly appealing to private investors looking for easily controlled supply chains and access to China's most important trade route.

Together, the ten Southeast Asian countries make up the ASEAN organization. For the past couple of years, the focal point of China-ASEAN relations has been the escalating tensions due to territorial and maritime disputes in the South China Sea. ASEAN, which is an enduring partner of the US, openly rejects China's “nine-dash” line which China claims grants its sovereignty over the majority of the sea, and by extension its resources, as a historical right. China, for its part, utilizes its political, economic and military superiority to coerce the ASEAN states into submission. Nearly 60% of Chinese maritime trade flows through the South China Sea to the Strait of Malacca towards the Indian Ocean.

Increasing tensions in the region with the ASEAN states as well as the US has left both the Chinese government and Chinese private investors looking for alternative ways of advancing their interests. It's through BRI that China has been able to insert itself in Southeast Asian politics, economics and civil society. Racked by instability, poverty and corruption the short-term loans provided by Belt and Road are incredibly alluring to the ASEAN states. And such loans become even more enticing when they come with the promise of infrastructure development, employment opportunities and delayed repayments. As such, many Southeast Asian countries have accepted Chinese investment in the short term without considering their long-term implications. Belt and Road investment and development in Southeast Asia will be aimed at mitigating tensions in the South China Sea and further entrenching Chinese politics and economics with the ASEAN states to protect Chinese national interests. These interests include the free and undisturbed passage of Chinese maritime trade, the recognition of the “nine-dash line” as a legitimate historical claim, and the establishment of a solidified Chinese sphere of influence over the region to counter the presence of the US.

Nevertheless, ASEAN maintains a stable and enduring relationship with the US to counter China's political influence in the South China Sea. Militarily speaking, ASEAN is no match for the Chinese navy, and thus, these countries must rely on US presence in the region to defend their claims over the sea and protect their national interests. So while the ASEAN states veer towards China for economic relief they also rely on the US for security protection. In this sense, Southeast Asia is the perfect example of hedging in practice and how China is using Belt and Road sponsored investment as an attempt to fully incorporate Southeast Asia into their sphere of influence.

Given China's clear and strict policy of non-interference in the affairs of other states (a policy that sets it apart from the US) it will use BRI sponsored investment and infrastructure development to mask its true intentions; which are to expand its influence over Southeast Asia at the expense of other countries' autonomy and sovereignty to favor its stake over the South China Sea. Such is the case of Indonesia, where China has been increasingly investing and politically engaging in the past year. Recently, aside from becoming Indonesia's largest trading partner, China has also sped up construction on the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Railway (a crucial project within the original Belt and Road blueprint) and settled total investment for it at $1.2 billion. Additionally, in February of 2023, Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang visited Indonesia, where he met with President Joko Widolo to discuss the future of Indonesia-China relations which include: modernization through cooperation, economic integration and regional stability. Gang's visit to Indonesia and Beijing's urgency to finish construction on the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Railway both come at a time in which Beijing desperately needs Indonesia's support and its influence as Chairman of ASEAN for 2023 to combat increased US presence in the region. Ultimately, China will continue to engage both economically and politically with Indonesia throughout 2023 to fully integrate it, and the rest of ASEAN, into the Chinese sphere of influence and isolate the US.

As post-pandemic economic recovery becomes a priority for ASEAN, China will take this opportunity to further expand BRI through trade and infrastructure development in the short-term. Over the next couple of years closer China-ASEAN relations will bring relative stability to the South China Sea. However, once the post-pandemic "high" of economic recovery stabilizes, China will shift its focus towards other regions of Asia to ensure the future development of BRI over the long-term and expand their sphere of influence to become a global power rather than just a regional one.