In the image

Three RAN vessels conducting a replenishment at sea [Australian Department of Defence]

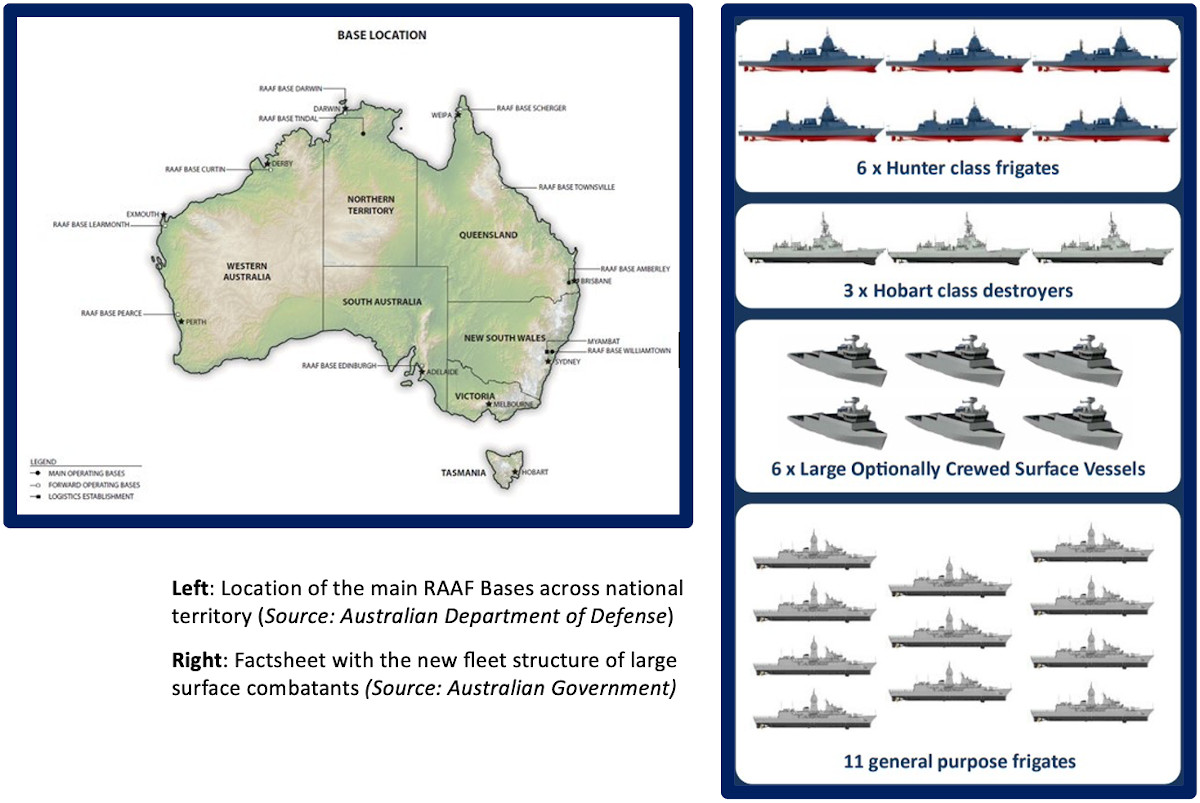

The Australian Government has finally unveiled the new fleet structure design for the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), several months after the 2023 Defense Strategic Review initially addressed the need for “an enhanced lethality surface combatant fleet, that complements a conventionally-armed, nuclear-powered submarine fleet.”

The long-awaited fleet structure design comes amid the growing challenges and constraints faced by the RAN, including the need to replace its ageing Anzac-class frigates and build the overall size of the Australian fleet, while minimizing as much as possible the huge economic costs derived from new naval procurement programs and addressing the acute workforce shortages both in the Navy and the national shipbuilding industry.

Indeed, the new fleet designed has garnered huge expectations among Australian and international naval analysts over the past months (including yours truly), and while it may still be too early to jump into solid conclusions, it is worth reviewing its background in the 2023 Defense Strategic Review (DSR) and the main efforts described in the recently published document. In the words of Australian naval expert Jennifer Parker, “it is a historic day when the government has finally agreed to support an enhanced surface combatant fleet capability for the Royal Australian Navy.”

Undoubtedly, the new fleet structure design unveiled by the Albanese Government is significantly better than many would have initially expected—at least on paper. It fulfills the need of a much-need desired fleet expansion beyond the traditional ceiling of 20 surface combatants, although details on the specific capabilities for many of them are yet to be further specified. Moving forward, workforce shortfalls and economic costs associated to the procurement of new classes of vessels will remain the main obstacles for Australia.

2023 Defense Strategic Review

Reflecting upon the numerous changes their strategic environment has been experiencing—and will keep experiencing—the 116-page document had a clear focus on the growing Chinese military threat across the Indo-Pacific region; to such extent that it didn’t even mention the Russian Pacific Fleet, whose force of nuclear—and conventionally—powered submarines remains a force to be reckoned with. At the same time, it acknowledged the fact that Australia is no longer isolated from strategic competition in that same region. On the contrary, its role has become more relevant than ever, and requires urgent action to design the necessary defense capabilities.

As I argued back in July, the DSR is a comprehensive document, published at a crucial time for the Australian Defense Forces (ADF). It highlights the challenging nature of their strategic environment, as well as the imminent need to react against all growing threats and risks found within it. Although the maritime section was certainly not as extensive as expected, the review offered several key ideas for the future of Australian capabilities at sea. With China as the main concern for both national and regional security, the review recommended the adoption of a defense strategy based on denial:

“For Australia, this strategy of denial must be focused on the primary area of military interest […] The development of a strategy of denial for the ADF is key in our ability to deny an adversary freedom of action to militarily coerce Australia and to operate against Australia without being held at risk.”

The region of main military interest, as defined later in the document, is based on a line of forward deployment that encompasses a network of bases and ports stretching “from Cocos Islands in the northwest, through RAAF bases Learmonth, Curtin, Darwin, Tindal, Scherger and Townsville”. Immediate upgrades and development of them are also recommended, so that they make it possible for this line encompassing half of the Australian coast, to provide with strategic depth for the ADF. Through the coordination of these bases, which extend across the northern half of their national coasts, Australia expects to enhance its ability to monitor the waters adjacent to it and strengthen their denial strategy against any unwanted presence.

Yet, in spite of its great ambitions, the DSR did not provide a definitive version on how the new fleet structure would be designed to meet the strategic requirements of the review. As ascertained back then by professor Jennifer Parker,

“The structure of the surface fleet remains a quandary, and a surprising one for the DSR team to delay solving given the urgency of the strategic situation it describes […] The DSR team (at least in the unclassified version of its report) avoided recommending specific capabilities as it did for the land and air domains.”

Those capabilities have now been defined and published in the new Independent Analysis into Navy’s Surface Combat Fleet.