Stakeholders in the DRC conflict

The M23

The March 23 Movement, known as M23, is a Tutsi-led rebel group that emerged in 2012 in the eastern DRC, and which is primarily active in the North Kivu province. The group was formed by former members of the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP), itself a Rwandan-backed militia composed largely of Congolese Tutsis, many of whom had historical ties to Rwanda, as previously discussed.

The CNDP itself grew out of earlier Rwandan-aligned movements, including the Congolese Rally for Democracy (RCD), which had an important role in the Second Congo War and was viewed as a Rwandan and Ugandan proxy force. Over time, these rebel groups repeatedly resisted integration into national institutions.

M23 gets its name from the March 23, 2009 peace agreement between the CNDP and the Congolese government. The accord had promised to integrate CNDP fighters into the Congolese army (FARDC), protect minority groups such as the Tutsis, and provide for a fairer distribution of resources. When the Congolese government allegedly did not fulfill these obligations, many ex-CNDP soldiers defected and rallied to form M23.

M23 claims to be defending Tutsi communities in eastern Congo against Rwandan Hutu militia threats, specifically the FDLR. But aside from this ethnic motivation, M23's actions increasingly appear driven by geopolitical interests and control of mineral-rich territory. In fact, some reports suggest that M23 generates at least $800,000 per month from levying taxes and controlling production in Rubaya alone.

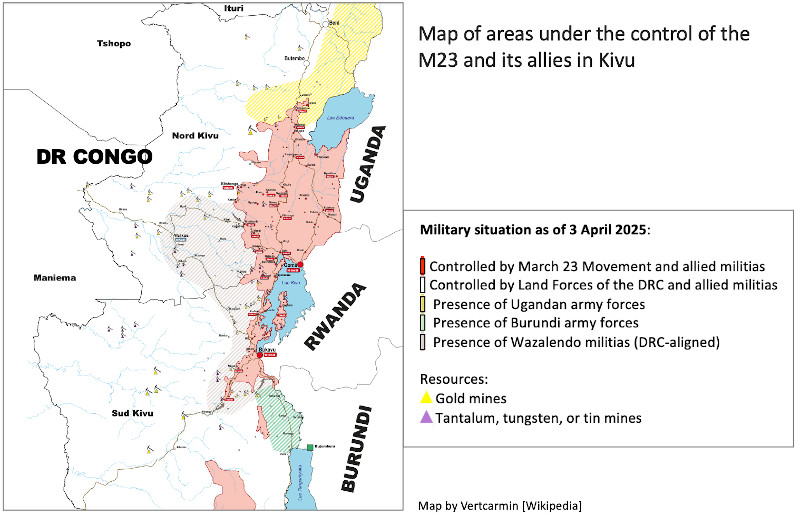

After lying low for nearly a decade, M23 returned in late 2021, attacking Congolese troops and capturing strategic towns. The rebels had captured the border town of Bunagana in 2022, and as of April 2025 they control large areas of North Kivu, including Walikale, Goma, and Bukavu. These gains have raised fears of renewed regional conflict, especially with allegations of Rwandan and Ugandan support.

Rwanda

The DRC government, the United Nations, the United States, and France have repeatedly accused Rwanda of supporting the M23 by providing them with weapons and direct assistance. Rwanda denies these claims, but a UN report from 2022 indicated strong evidence that Rwandan troops fought alongside M23.

Rwanda’s interest in eastern Congo is strategic and economic, targeting Hutu militias like the FDLR, who fled the 1994 genocide. These groups, accused of harboring genocidaires, remain a pretext for Rwandan military presence in the DRC. Another way of looking at this, however, is that Rwanda has over the years been trying to establish a buffer zone along the DRC-Rwanda border, keeping them further away from Hutu armed groups in eastern DRC while retaining influence in the region.

This buffer zone overlaps with Rubaya, Masisi, Walikale, and Goma’s mineral belt, where control equals access to coltan, cassiterite, and gold minerals that the global tech and energy sectors depend on. According to multiple investigative reports, most gold smuggled from the DRC into international markets passes through Rwanda and Uganda.

Despite its limited domestic gold reserves, Rwanda exported nearly 50 tones of gold valued at over $885 million. All this gold is largely undeclared at source and likely originates from Congolese artisanal mining zones, mainly in the Kivu provinces.

In addition to gold, Rwanda is suspected of benefiting from coltan smuggling routed through border towns like Gisenyi (Rwanda) and Goma (DRC). Rubaya mines in the Masisi region, which are currently in the hands of M23, are estimated to produce hundreds of thousands of dollars per month in taxes paid to rebel authorities. These minerals are transported over Lake Kivu or along road networks into Rwanda, only to be shipped out as of Rwandan origin under ambiguous traceability systems.

The European Union imposed sanctions on Rwanda’s Mines, Petroleum and Gas Board and several senior officials in 2024 as an attempt to disrupt the illegal supply chains. However, the sanctions were too little and too late. Rwanda had already developed solid infrastructure for smuggling and diversified its traders, especially the UAE, which imports a high percentage of Africa’s undeclared gold every year.

The disconnect between Rwanda’s declared production and export volumes as well as discrepancies between customs data and national mining registries has raised red flags. Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) remains unregulated in eastern Congo and southern Rwanda, enabling both governments and rebel proxies to launder minerals through official channels.

Ultimately, Rwanda’s stake in the conflict is twofold: security wise, it’s suppressing Hutu militias across the border; and profit, as it is facilitating the movement and export of conflict minerals under state-sanctioned or proxy structures.

This dual role makes Rwanda both a military actor and an economic stakeholder, profiting from a conflict it claims to be not part of.

Uganda

Uganda is accused of secretly supporting the M23. The Ugandan president has let M23 use Uganda for supply routes, which raises questions about the country’s true intentions. Uganda has a history of involvement with Congo’s resources, especially between 1998 and 2003. This past suggests money might be more important to Uganda than peace. Ugandan troops are in eastern DRC, officially to fight terrorist groups like the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), but this raises doubts about Uganda’s real motives.

The African Gold Refinery (AGR) in Entebbe drew international scrutiny when its exports surged to $377 million in 2017, prompting accusations that it was laundering conflict gold. Though AGR’s current operational status is unclear, its activities cemented Uganda’s role as a regional gold hub, blurring the line between legal and illicit supply chains.

Moreover, Uganda views the Eastern DRC not only as an economic asset but as a security frontier vital to protecting strategic national assets, including the oil installations close to the Congolese border. Titeca highlights that Uganda initiated Operation ‘Shujaa’ to secure the area from threats like the ADF and to protect economic interests like road construction.

President Museveni explicitly justified road infrastructure funding in Eastern DRC stating, “We need to trade with Congo. It will enable us to get more resources to deal with the roads that we have not been able to do.” Uganda’s business activities in eastern DRC are not only profitable but also part of a larger strategy affecting its politics and security planning.

In sum, Uganda’s approach in eastern DRC is multifaceted: militarily, it uses operations against the ADF to justify its presence; economically, it benefits from gold, timber, and other resource trades, often linked to smuggling networks; and politically, it secures leverage in the region, shaping alliances with local and international actors (including M23) to serve Kampala’s strategic goals.

Russia

Though not a frontline actor like Rwanda or Uganda, Russia has emerged as a shadow player in the Congolese conflict, using a combination of arms diplomacy, public image manipulation, and covert economic ambitions to expand its influence in the region.

In 2021, the Russian government delivered 10,000 Kalashnikov rifles and 3 million rounds of ammunition to the DRC. Though framed as a military aid package, the gesture mimicked Russia’s model in the Central African Republic, where arms transfers were soon followed by the deployment of Wagner mercenaries, now rebranded as ‘Afrika Corps.’ The visit of Wagner-linked diplomat Viktor Tokmakov to Kinshasa in 2021 further showed Moscow’s interest in deepening security ties.

Russia’s presence in Congo remains largely symbolic and transactional. President Tshisekedi walked back a defense minister’s claim that Russia would build military bases in the country, likely due to consternation of alienating Western partners and rekindling the ‘Lumumba syndrome,’ the fear of international abandonment or assassination for siding with Russia.

Russia’s strategic model in Africa offers political support and military hardware in exchange for long-term access to natural resources. This ‘security-for-resources’ equation has funded Russian interventions in Mali, Sudan, and the Sahel, where Wagner mercenaries receive billions in gold.

Russia’s influence in the DRC may be growing. Congolese citizens disillusioned by Western inaction toward Rwanda’s aggression have taken to social media praising Wagner for its efficiency, claiming that, if deployed, M23 “would flee back to Kigali.” Whether genuine or state-amplified, these narratives reflect growing pro-Russian sentiment among segments of the Congolese public.

China

China’s involvement in the DRC is rooted in the mineral wealth of the nation, particularly in the copper and cobalt sectors, where Chinese companies dominate in the extraction, processing, and exportation. China controls over 60% of the DRC’s cobalt production and owns 85% of the global processing capacity for these strategic minerals as of 2024 placing the DRC at the center of China’s global supply chain for electric vehicle batteries, electronics, and green energy technologies.

China has cemented its presence in key mining regions, like Kolwezi and Lubumbashi. However, many of these projects have been marred with human rights abuses. Forced evictions, arson, and rape have been reported by Amnesty International and local NGOs linked to Chinese-financed mining operations. For example, the Zijin Mining group (via COMMUS) was accused of setting houses on fire at Cité Gécamines without a resettlement plan. In Mukumbi, displaced residents were reportedly attacked by armed staff who are working with a Chinese joint venture partner, Chemaf.

Since the resurgence of M23 in 2022, the transparency of supply chains has drastically deteriorated. Jean-Claude Katende Okenda, director of NGO Sentinel Natural Resources, argues that traceability systems once used to certify mineral origins have collapsed. With rebel zones funneling minerals like coltan into Rwanda, then on to China, Okenda describes China as “the darkness in the supply chain,” benefitting from conflict minerals without accountability.

China’s neutrality is also being tested. Traditionally committed to non-interference, Beijing broke with convention in February 2025 by publicly urging Rwanda to cease its support for the M23 and withdraw its forces from Congolese land, a rare direct rebuke that speaks to concern over the security of Chinese investments.

Militarily, China also arms both Rwanda and the DRC. Reports have confirmed that Chinese armored vehicles, anti-tank weapons, and drones have been transferred to the Rwandan army. Norinco and Deekon Group are only some of the PRC companies that have sold uniforms, arms, and even established drone R&D facilities in Uganda. In 2023, China also sold the DRC combat drones CH-4 to export, further supporting its contribution to the local arms race.

Weapons seized from M23 forces by the Congolese military include Chinese-made equipment, pointing to indirect complicity. Analysts argue that M23’s weaponry largely traced to Rwanda and Uganda, includes PRC-origin weapons now being used in attacks on civilians near Goma.

China’s economic calculus is simple: mineral access is in the national interest. But the cost to Congolese civilians is disastrous, especially as Chinese mining investment moves into conflict-adjacent areas. As human rights violations intensify and the local war deteriorates, China’s dual roles as investor and arms supplier present an obvious contradiction to its claimed neutrality, and a dangerous permissiveness in the face of war crimes.

Multinational Corporations

While China dominates the narrative of DRC’s mining sector, Western multinational companies are equally complicit in the continuation of the conflict and the enabling of human rights abuses. Apple, Alphabet (Google), Microsoft, Dell, and Tesla were among the firms named in a 2019 suit filed in Washington D.C. by Congolese families which alleged that the companies knowingly benefited from cobalt that had been mined by children as young as six. These children were reported to have earned less than a dollar per day ($0.81) and were forced to work in dangerous conditions where they got injured, died, and suffered trauma.

Siddharth Kara, a leading scholar on modern slavery, estimates that 35,000 children are involved in cobalt mining in the DRC. Despite ample documentation and repeated calls for action, companies have failed to ensure traceability or accountability in their supply chains. Kara argues that most corporate pledges serve as PR tools, not genuine reform.

In December 2024, the DRC filed a criminal complaint against Apple in France and Belgium, accusing it of sourcing minerals from conflict zones. Though dismissed in February 2025, the case raised awareness about how even the most publicly ‘responsible’ companies can be shielded by opaque global systems.

Apple, in its public reports, claims to follow OECD due diligence guidelines and conduct third-party audits. Yet critics argue these measures are insufficient. As Jean-Claude Katende Okenda puts it: “No one really has an interest in making the supply chain transparent, not the authorities in Rwanda or Congo, the middlemen, or Chinese and Western companies.”

Until global corporations are legally required to ensure ethical sourcing, the DRC’s minerals will continue to fuel cycles of exploitation, violence, and impunity.

The European Union and the United States

The European Union and the United States have several stakes in their relationship with the DRC and Rwanda particularly in the context of the conflict. These interests include access to critical mineral sources, mainly to compete with China in the region. They also value maintaining regional security partnerships.

On the 13th February 2025, a broad majority vote by the European Parliament call for the suspension of theMemorandum of Understanding on Sustainable Raw Materials with Rwanda it had subscribed in 2020, due to Rwanda’s military presence and its alleged support to the rebel group and the lack of traceability and transparency mechanisms regarding how the minerals were sourced. However, the EU’s Global Gatewayagreement with Rwanda, signed in 2024, which facilitates mineral trade under the pretense of sustainable partnerships, has not been formally revoked.

On March 19, 2025, it was revealed that Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi had made President Donald Trump a trade-off proposal: assist militarily in ending the M23 rebellion in exchange for US access to cobalt, tantalum, and lithium. In a letter to Trump, Tshisekedi framed the proposal as an opportunity to advance America’s technological edge. The proposition on the table is mining concessions for the recently created US Sovereign Wealth Fund.

Tshisekedi made his offer in tandem with parallel negotiations with Erik Prince, the founder of Blackwater and ally to Trump. The proposal has a private security mission to crack down on tax evasion within the mining industry, essentially privatizing state revenue collection.

Tshisekedi is betting on that Washington, seeking to cut China’s grip on strategic minerals, will provide security support denied by earlier administrations. The move also shows possible deterioration in Sino-Congolese ties. Congo state-owned miner Gecamines has turned down a number of offers by Chinese firms, including Norin Mining’s $1.4 billion offer to acquire Chemaf, raising doubts on long-term compatibility.

Ultimately, the dilemma remains: foreign governments cannot impose solutions on sovereign nations, yet current policies fail to disincentivize predatory behavior. Without consistent enforcement, coordinated international pressure, and support for internal reform within the DRC, diplomatic and economic tools remain insufficient to shift the underlying dynamics of exploitation and violence.

Implications for stakeholders

The actions taken by the involved parties reveal broader strategic interests that go beyond peacebuilding. These actions are deeply intertwined with the region's vast natural resources, geopolitical competition, and security concerns that draw the attention of the stakeholders and what they might earn out of this conflict.

The DRC is faced with the threat of the M23 potentially advancing further, fundamentally challenging the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Congolese state. It feeds into the broader narrative of governance issues, including corruption, kleptocracy, and lack of neutrality in managing conflict. Should M23 succeed in consolidating control over eastern territories, it could erode long-standing norms regarding the inviolability of colonial-era borders. This may signal a shift toward an era of hard-power politics in the region, where territorial control and access to natural resources are increasingly pursued through military means, potentially setting a destabilizing precedent for other contested border zones in Africa. The DRC is attempting to leverage geopolitical competition between China and the USA over its minerals by offering it to the US.

The M23 profit from the revenue generated from the minerals and from the taxation the financial resources the exploitation of resources provide to sustain its military operations and recruit even more fighters. These resources allow M23 to function increasingly like a conventional army, rather than an irregular militia. External support further reinforces its capacity. From the group’s perspective, gaining territory and influence can also be framed as a way to ensure security and protect the interests of its Tutsi ethnic base, especially given past experiences of displacement, violence, and marginalization in the region.

For Rwanda, the primary implication is the alleged economic benefits derived from controlling or facilitating the trade of minerals from the DRC. The present instability allows Kigali to exercise regional power while generating significant revenue, particularly through the control of smuggling routes and cross-border commerce. Nevertheless, if the DRC’s proposed mineral-for-security deal with the United States proceeds, Rwanda could be forced to change its approach or suffer greater diplomatic and economic pressures. While short-term strategic and economic gains may come Rwanda’s way, its alleged support of armed groups can have spillover effects, including increased refugee flows, border instability, and the possibility of other armed groups taking a direct attack on its land.

Uganda has a direct security interest in the stability (or instability) of eastern DRC due to its shared border and presence of various armed groups. A specific motivation is to protect its oil exploitation at Lake Albert. The discrepancy between Uganda’s low official gold production figures and its higher export figures strongly supports the conclusion that Uganda also earns by facilitating the export of gold originating from outside its land.

Washington’s engagement in Rwanda, through sanctions and backchannel negotiations, shows interest but lacks strategic coherence. Tshisekedi’s mineral-for-security deal tests the US Africa policy’s ability to move into a transactional partnership. The US wants influence but hesitates to pay the cost of sustained involvement. Meanwhile, the EU is caught between normative posturing and geopolitical paralysis, with sanctions on Rwandan officials and temporary suspensions.

Both Beijing and Moscow publicly condemn M23 offensives and support the DRC’s sovereignty, yet neither has pressured Rwanda enough. China benefits from its sales of weapons to both Rwanda and DRC, masking sourcing opacity and enabling mineral extraction without accountability. Tshisekedi’s outreach to the US threatens China’s dominance and its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Beijing must double down or risk losing ground to American entry in mineral-rich eastern DRC.

Conclusion

As of May 2025, the eastern-Congo conflict remains unresolved; the initial Qatari-brokered ceasefire fell apart on May 2 when M23 forces captured Lunyasege, and though Kinshasa and Kigali have submitted draft peace treaties in Washington, signing is not expected until late May and only if linked to US backed supply chain agreements over critical minerals. Meanwhile the M23 is building its proto-administration and capturing additional territory. These dynamics show the structural incentives driving the war. Temporary pauses in fighting, while welcome, do not address the structural violence and exploitation in eastern Congo.

What is happening in the DRC is not a failure of diplomacy or peacekeeping; it is rather the success of an international system that rewards instability when it advances strategic and economic interests. The war keeps going not because it is unsolvable, but because there are too many actors, states, corporations, institutions who have a stake in maintaining the illusion that it is.

Geopolitical influence today is not exercised through traditional occupation, but through access: to minerals, to markets, to proxy networks that offer deniability. China, Rwanda, Uganda, and even Western companies have all mastered the art of extracting value while disclaiming responsibility.

The M23 movement, while born of the Rwandan genocide, has evolved into a group driven by a desire to dominate and exploit resource-rich land. The rebels are no longer only protecting Tutsi communities but focusing as well on the minerals that power the new world.

The DRC will never know peace unless it becomes economically and politically independent, a possibility, under the current situation is far from sight. The Congolese state must first address its own decay. Until Kinshasa dismantles its patronage networks, stops arming irregular militias, and cleanses the military of corruption and abuses, any talk of sovereignty will be hollow. No outside power whether the United States or China can build peace on a foundation being actively hollowed from within.

It is clear that this conflict will not soon end, the every-day consumer has accepted the suffering of the congolese people as a permanent reality. Until that changes, the war will continue, not because it must but because it's profitable.