Evolving ideological groupings

ECR (European Conservatives and Reformists) is a moderately Eurosceptic bloc composed by national conservatives, while critical of deeper integration, it supports selective EU initiatives like enlargement. On the other hand, ID (Identity and Democracy) takes more of a hardline nationalist stance, opposing EU integration and promoting restrictive migration policies.

In 2024, ID fractured, which gave rise to two new far-right groups: Patriots for Europe (PfE), led by Le Pen’s RN and Orbán’s Fidesz, and Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN), centered around Germany’s AfD. Non-Attached (NI) members include parties too radical or isolated to join any group.

On the left, Greens/EFA (focused on climate and rights) lost ground in 2024, dropping 19 seats, reflecting rural backlash to green policies. The Left (formerly GUE/NGL) made modest gains but remains fragmented.

Eurosceptic parties, once marginal, now wield certain influence. The 2024 EP includes 25% MEPs from openly anti-EU or reform-sceptic parties, up from 15% in 2014. While certain groups such as PfE and ECR reject federalism, their strategies vary: the ECR (led by Italy’s Giorgia Meloni) advocates for a ‘Europe of nations,’ whereas other have sovereignty reclaims. This ideological spectrum complicates Eurosceptic unity but amplifies their disruptive potential in key votes on EU integration.

Left-wing forces have struggled to counter this rightward shift. The Greens/EFA group lost 19 seats in 2024, which brough it down to 53, while the Left (GUE/NGL) saw modest gains with 6 more seats. Perhaps reflecting a bigger trend against climate policies which have been perceived as economically punitive, particularly in agrarian regions like Spain and Poland.

Decline of traditional blocs

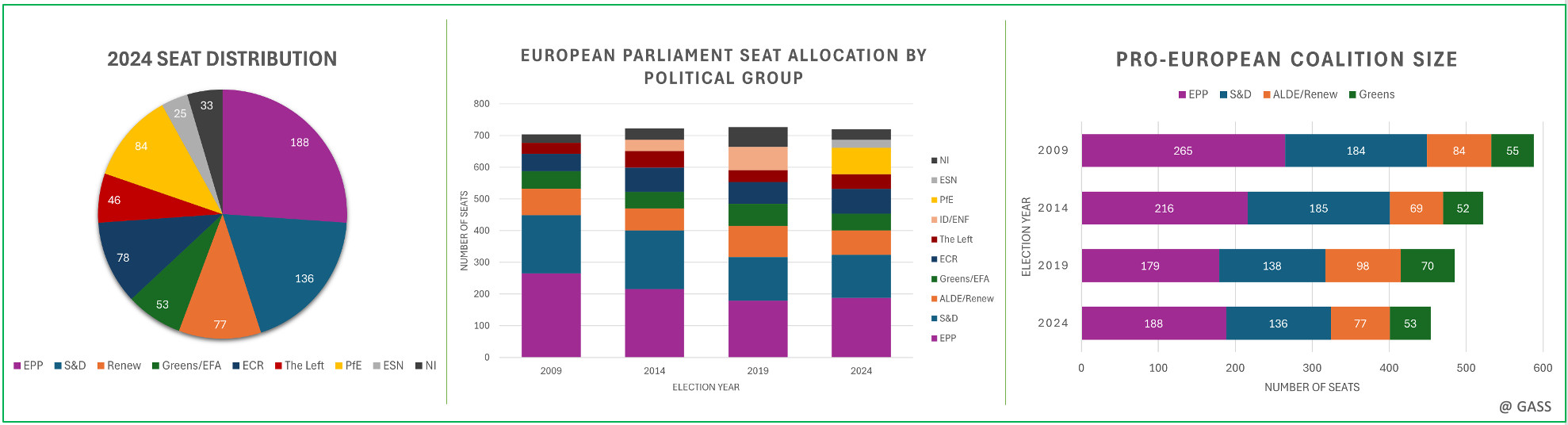

The decline of mainstream parties is evident in seat counts. In 2004, the EPP held 279 seats and S&D 199 (a combined majority). By 2019, EPP had just 179 and S&D 152. This erosion reflects both national trends (declining support for centrist parties) and pan-European dynamics.

The 2019 elections marked the first time the EPP-S&D coalition lacked a majority without additional partners, the EPP group had 179 seats and S&D 138 (out of 751 total), a sharp decline from previous terms. . The weakening of these traditional blocs opened space for newer, more agile political formations. The seat losses for EPP and S&D reflect both domestic and transnational trends. Across member states, the traditional center‐right and center‐left parties have underperformed in successive EU elections.

Rise of Liberals, Greens, and the Right

The liberal Renew Europe group and the Greens/EFA have grown in seats from 2014 to 2019. Renew Europe gained 40 seats from 69 to 101, thanks to new centrist pro-European parties like France’s Renaissance. The Greens rose from 52 to 73 seats, which aligns with an increase in environmentalist sentiments in countries like Germany and France.

Meanwhile, the ID group rose from 36 seats (as ENF) in 2014 to 73 in 2019. In 2014, the ENF/EAPN coalition (including Le Pen’s FN/RN and Salvini’s Lega) had 36 seats; by 2019 its successor (ID) held 73 seats. On the other hand, the ECR also remained strong, and new formations like PfE and ESN emerged in 2024.

The 2024 election cemented this pattern. The overall alliance of centre parties (EPP + S&D + Renew + Greens) still remains the largest coalition, but its collective share has somewhat eroded. In practice, two new factions emerged on the right: in July 2024, a Patriots for Europe group was formed (uniting Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz, Marine Le Pen’s RN, Italy’s League, etc.) and an Europe of Sovereign Nations group was created around AfD and PiS. The official Parliament data shows the new Patriots for Europe group had 84 seats (with RN contributing 30 and Fidesz 14 of those). Thus, the right‐wing/pro‐autonomy bloc in the new EP is more splintered into multiple groups and a significant number of MEPs now sit outside any group or in very small ones.

Together, these far-right and nationalist groups now rival S&D in size but remain divided on key issues such as Ukraine, trade, and internal EU reform.

Electoral systems fuel fragmentation

The EU’s use of proportional representation (PR) for EP elections encourages party diversity. With few national thresholds—14 member states have none—small parties can secure seats with minimal support. For instance, in the Netherlands, a party can win a seat with just 0.67% of the vote, in comparison to other countries like Germany that have a 3% threshold and Italy 4%, such thresholds exclude very small lists.

Furthermore, variations in national electoral laws: the use of regional vs. national lists, or open vs. closed lists, can further diversify the composition of EP delegations. While these rules are meant to enhance representativeness, they also produce an assembly fragmented along both national and ideological lines.

Coalition dynamics in a fragmented parliament

Fragmentation has made stable majorities harder to build. The once dominant EPP–S&D ‘grand coalition’ is now insufficient to govern alone. Traditionally, the centre-right EPP and centre-left S&D blocs together held comfortable majorities, for instance, 65% of seats in the 1999–2004 term. That so-called ‘grand coalition’ dominated EP business for decades. But as their share has fallen, formal or ad hoc coalitions have widened. In the 2019–24 Parliament, EPP (179 seats) plus S&D (138) only had about 44% of seats. Since 2019, a new centrist alliance of EPP, S&D, and Renew Europe has become the de facto governing bloc.

However, informal and issue-specific coalitions are now the norm. On social issues, S&D, Renew, Greens, and The Left often collaborate. On economic or security matters, EPP may align with Renew and ECR. No single coalition dominates across all policy areas and importantly, none of these blocs includes all right- or left-wing members.

One immediate effect of fragmentation was visible after the 2019 elections: the selection of the European Commission President. Lacking a clear majority, the Parliament could not simply install the EPP’s lead candidate (Spitzenkandidat) as Commission chief, as had been attempted in 2014. Eventually, EU leaders nominated Ursula von der Leyen (from the EPP) as a compromise, and she won confirmation by the EP with just 383 votes, which is a margin of only 9 votes above the required majority, compared to Juncker’s 422 votes five years prior. Her confirmation was only possible by assembling support from three pro-EU groups – the EPP, S&D, and Renew. Coalition-building has become more challenging: the once-stable centre had to court a third or even fourth partner, and the cohesion of those alliances can’t be taken for granted.

Despite these challenges, legislative productivity remains high. Between 2019 and 2024, the EP passed 370 laws, which is only slightly fewer than the 401 passed in the previous term, with COVID and Brexit disruptions likely responsible for the drop instead of a legislative lock. In practice, committees and plenaries have adapted: hybrid coalitions meet behind closed doors and votes are often negotiated in advance by multiple group leaders. Still, the increased number of parties can slow consensus-building.

Implications for governance and the 2029 outlook

Fragmentation complicates governance, building majorities now requires multi-group alliances that vary on ideological divides. It further reflects deeper transformations in member state politics, such as declining trust in mainstream parties, rising nationalism, and growing issue-based movements (e.g., environmentalism, Euroscepticism).

Future parliaments are likely to remain pluralistic and contentious. EU institutions should prepare for more frequent ad hoc coalitions, greater negotiation complexity, and the potential for legislative deadlock or ideological polarisation. While fragmentation brings more voices into EU politics, it also increases the difficulty of achieving strategic consensus. While legislative productivity has held up, the future may see more polarisation, especially as ideological outliers grow in strength.

Nonetheless, a more fragmented Parliament is ‘more representative’ of Europe’s diverse electorate. It can incorporate a wider range of viewpoints and ensure that more citizens see their chosen party represented in Brussels. This could bolster the EP’s democratic legitimacy if handled well. On the other hand, a highly fragmented legislature may struggle to provide stable leadership at the EU level. The 2029 Parliament will have to approve and work with a new European Commission, pass complex legislation (perhaps on digital transformation, enlargement, or new fiscal rules) and respond to any crises that arise. If no clear majority coalition emerges, the process of building ad-hoc majorities on each issue could become more fraught.