En la imagen

View of Gwadar Port in 2018 [Xinhua]

Chinese maritime ambitions have been a cause of concern among many Western and non-Western nations for some time now. One of the most recent reports addressing Chinese maritime ambitions and port investments concluded that “China is shopping […] At the top of its wish list would be permanent, secure military installations with support, logistics and repair infrastructure. The ports themselves would be deep water and secure; in countries with which China enjoys good relations; and ideally near strategic choke points.” One of the most relevant examples of such ambitions is found in the Port of Gwadar, located in Pakistan. For years, concerns have been expressed over the fact that China could decide to use many of its foreign ports as naval bases for the PLA Navy (PLAN).

The commercial and (potential) military value held by the Port of Gwadar is better understood through the concept of China's “strategic strongpoints,” which makes reference to certain foreign ports with high strategic value, whose terminals and commercial zones are operated by Chinese firms. These strongpoints enable the Chinese Government to strengthen commercial, diplomatic and economic ties with the host country, allowing the latter to make use of the facilities as well. Most importantly, these ports have the potential to be used for military purposes, predominantly during wartime

The following brief addresses the potential for dual use of the Port of Gwadar based on its activities and the wider context of Chinese maritime ambitions in the Indo-Pacific region. With such analysis, it is able to grasp what are the characteristics of Chinese foreign ports that allow them to be used for both commercial and military purposes.

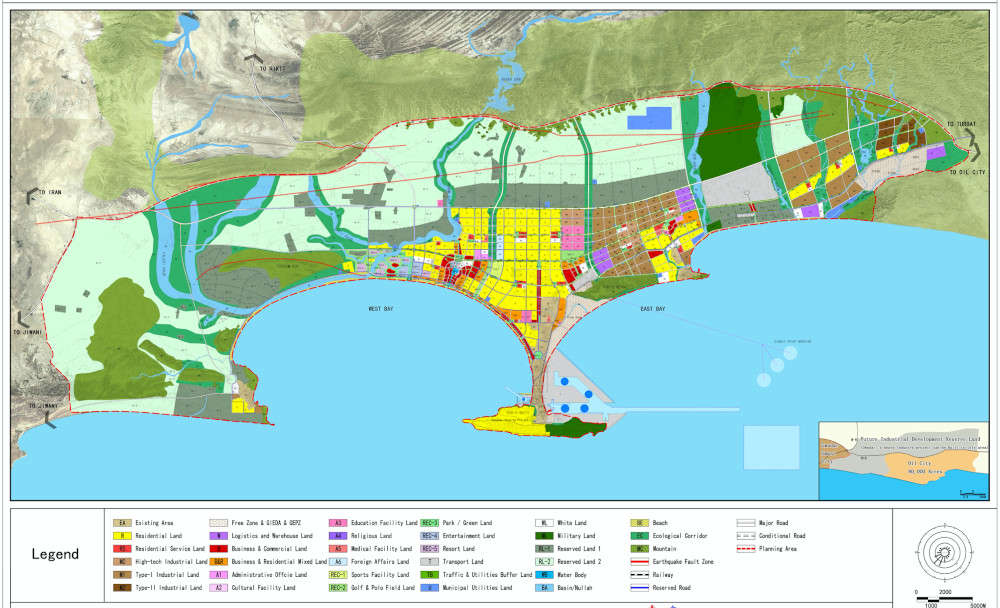

Port of Gwadar

The port of Gwadar is located in the South of Pakistan, relatively close to the border with Iran. Its first stages became operational in 2008, but the port hasn't seen regular commercial service since then. While it is primarily used for local artisanal fishing at the moment, it is intended that the population there will be eventually displaced to host all kinds of commercial activity. With the continuous growth of Chinese maritime commerce and naval activity, this particular port has gathered the attention of many analysts due to its strategic location. Chinese analysts view it as a top choice for establishing a new overseas strategic strongpoint, owing to its prime geographic location and strong Sino-Pakistani ties. Not only does it allow the PRC to strengthen its cooperation with Pakistan, but it also provides it with an alternative access to the Arabian Sea in case the Strait of Malacca is blocked. As ascertained by Drazen Jorgic, “Beijing and Islamabad see Gwadar as the future jewel in the crown of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship of Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative to build a new ‘Silk Road’ of land and maritime trade routes across more than 60 countries in Asia, Europe, and Africa.”

According to China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI)'s Isaac Kardon, Connor Kennedy and Peter Dutton, there are several traits in common between the most relevant strongpoints operated by China in the region. The first is their strategic geographical location. Most, if not all, ports are located at geographically vital locations, close to important sea lines of communication (SLOCs) and providing access to important bodies of water. Second, management coordination. They are a product a high-level coordination between state-owned enterprises, Chinese party officials, and other private firms. Third, they have a comprehensive commercial scope. They are part of a wider strategy followed by the government which encompasses the parallel development of rail, road, and pipeline infrastructure to support its Belt and Road Initiative. Lastly, the potential for military use. Ports are equipped dual-use functions which enable them to support military activity in case it was required, with vast storage facilities that could be used to store weapons, and piers which can support large PLAN vessels—including aircraft carriers.

Gwadar lies around 400 km east of the Strait of Hormuz, a narrow corridor that connects all countries in the Persian Gulf with the global markets, and through which the 40 % of China's imported oil transits. Additionally, Gwadar serves as an exit to the in-land commercial route that China has from its western part in Xinjiang Region, through Pakistan, down to the port in the Indian Ocean. In other words, it is the so-called Chinese “exit to the [Arabian] sea.” A corridor that in the future may serve as a brilliant geopolitical tool for China to maintain its control over the region. A key element of its importance, however, is it being the entry point from the Middle East region for the energy flows to China.

The Sino-Pakistan relations assure Chinese energy imports coming through Gwadar as an alternative to the Malacca Dilemma, viewed by some as a potential threat to Chinese national security. This concept refers to the reliance by China on the shipments that arrive through the Malacca Strait, a region between the Sumatra Island and the Malayan Peninsula that has Singapore to the east. Due to Singapore's closer ties with India and the US, China fears its energy supplies could be blocked. This would lead to a significant drawback in its economic evolution and growth.

Gwadar is another example, among the many in existence, which showcase Chinese reliance on its commercial activity as a means to attain a degree of national security. It shows the growing obsession of China for commercial growth, a focus that has in turn led China to deeply tighten its relations with Pakistan. In the words of Hu Jintao back in 2006 in an address at Islamabad, China is “deeply touched by the outpouring of brotherly affection of the Pakistani people. In the words of one Pakistani friend, such friendship is ‘higher than the Himalayas, deeper than the Indian Ocean and sweeter than honey.’” Additional references to the high importance of Gwadar for China can be found in Xi Jinping´s 2015 visit to Pakistan, where he stated the port was one of the four pillars of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), and pledged a Chinese investment of $46 million over the following 15-year period.

Gwadar is an asset for China, but one that still remains to be properly operated. It is linked to the transport infrastructure that the Chinese Government intends to build in Pakistan, and for now, China seems to be more involved in expanding its network of ports in Africa. But while that corridor is widely discussed as if it was operational, very little modern infrastructure has been built to date. This has raised concerns over the potential military use that China could give to it.