Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Entradas con Categorías Global Affairs Oriente Medio .

COMMENTARY / Marina G. Reina

After weeks of rockets being fired from Gaza and the West Bank to Israel and Israeli air strikes, Israel and Hamas have agreed to a ceasefire in a no less heated environment. The conflict of the last days between Israel and Palestine has spread like powder in a spiral of violence whose origin and direct reasons are difficult to draw. As a result, hundreds have been killed or injured in both sides.

What at first sight seemed like a Palestinian protest against the eviction of Palestinian families in the Jerusalem’s neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah, is connected to the pro-Hamas demonstrations held days before at Damascus Gate in Jerusalem. And even before that, at the beginning of Ramadan, Lehava, a Jewish far-right extremist organization, carried out inflammatory anti-Arab protests at the same Damascus Gate. Additionally, the upcoming Palestinian legislative elections that Palestinian PM Mahmoud Abbas indefinitely postponed must be added to this cocktail of factors. To add fuel to the flames, social media have played a significant role in catapulting the conflict to the international arena—especially due to the attack in Al-Aqsa mosque that shocked Muslims worldwide—, and Hamas’ campaign encouraging Palestinian youth to throw into the streets at point of rocks and makeshift bombs.

Sheikh Jarrah was just the last straw

At this point in the story, it has become clear that the evictions in Sheikh Jarrah have been just another drop of water in a glass that has been overflowing for decades. The Palestinian side attributes this to an Israeli state strategy to expand Jewish control over East Jerusalem and includes claims of ethnic cleansing. However, the issue is actually a private matter between Jews who have property documents over those lands dating the 1800s, substantiated in a 1970 law that enables Jews to reclaim Jewish-owned property in East Jerusalem from before 1948, and a group of Palestinians, not favored by that same law.

The sentence ruled in favor of the right-wing Jewish Israeli association that was claiming the property. This is not new, as such nationalist Jews have been working for years to expand Jewish presence in East Jerusalem’s Palestinian neighborhoods. Far from being individuals acting for purely private purposes, they are radical Zionist Jews who see their ambitions protected by the law. This is clearly portrayed by the presence of the leader of the Jewish supremacist Lehava group—also defined as opposed to the Christian presence in Israel—during the evictions in Sheikh Jarrah. This same group marched through Jerusalem’s downtown to the cry of “Death to Arabs” and looking for attacking Palestinians. The fact is that Israel does not condemn or repress the movements of the extreme Jewish right as it does the Islamic extremist movements. Sheikh Jarrah is one, among other examples, of how, rather, he gives them legal space.

Clashes in the streets of Israel between Jews and Palestinians

Real pitched battles were fought in the streets of different cities of Israel between Jewish and Palestinians youth. This is the case in places such as Jerusalem, Acre, Lod and Ashkelon —where the sky was filled with the missiles coming from Gaza, that were blocked by the Israeli antimissile “Iron Dome” system. Palestinian neighbors were harassed and even killed, synagogues were attacked, and endless fights between Palestinians and Israeli Jews happened in every moment on the streets, blinded by ethnic and religious hatred. This is shifting dramatically the narrative of the conflict, as it is taking place in two planes: one militarized, starring Hamas and the Israeli military; and the other one held in the streets by the youth of both factions. Nonetheless, it cannot be omitted the fact that all Israeli Jews receive military training and are conscripted from the age of 18, a reality that sets the distance in such street fights between Palestinians and Israelis.

Tiktok, Instagram and Telegram groups have served as political loudspeakers of the conflict, bombarding images and videos and minute-by-minute updates of the situation. On many occasions accused of being fake news, the truth is that they have achieved an unprecedented mobilization, both within Israel and Palestine, and throughout the world. So much so that pro-Palestinian demonstrations have already been held and will continue in the coming days in different European and US cities. Here, then, there is another factor, which, while informative and necessary, also stokes the flames of fire by promoting even more hatred. Something that has also been denounced in social networks is the removal by the service of review of the videos in favor of the Palestinian cause which, far from serving anything, increases the majority argument that they want to silence the voice of the Palestinians and hide what is happening.

Hamas propaganda, with videos circulating on social media about the launch of the missiles and the bloodthirsty speeches of its leader, added to the Friday’s sermons in mosques encouraging young Muslims to fight, and to sacrifice their lives as martyrs protecting the land stolen from them, do nothing but promote hatred and radicalization. In fact,

It may be rash to say that this is a lost war for the Palestinians, but the facts suggest that it is. The only militarized Palestinian faction is Hamas, the only possible opposition to Israel, and Israel has already hinted to Qatari and Egyptian mediators that it will not stop military deployment and attacks until the military wing of Hamas surrenders its weapons. The US President denied the idea of Israel being overreacting.

Hamas’ political upside in violence and Israel’s catastrophic counter-offensive

Experts declare that it seems like Hamas was seeking to overload or saturate Israel’s interception system, which can only stand a certain number of attacks at once. Indeed, the group has significantly increased the rate of fire, meaning that it has not only replenished its arsenal in spite of the blockade imposed by Israel, but that it has also improved its capabilities. Iran has played a major role in this, supplying technology in order to boost Palestinian self-production of weapons, extend the range of rockets and improve their accuracy. A reality that has been recognized by both Hamas and Iran, as Hamas attributes to the Persian country its success.

This translates into the bloodshed of unarmed civilians to be continued. If we start from the basis that Israeli action is defensive, it must also be said that air strikes do not discriminate against targets. Although the IDF has declared that the targets are bases of Hamas, it has been documented how buildings of civilians have been destroyed in Gaza, as already counted by 243 the numbers of dead and those of injured are more than 1,700 then the ceasefire entered into effect. On the Israeli side, the wounded reported were 200 and the dead were counted as 12. In an attempt to wipe out senior Hamas officials, the Israeli army was taking over residential buildings, shops and the lives of Palestinian civilians. In the last movement, Israel was focusing on destroying Hamas’ tunnels and entering Gaza with a large military deployment of tanks and military to do so.

Blood has been shed from whatever ethnical and religious background, because Hamas has seen a political upside in violence, and because Israel has failed to punish extremist Jewish movements as it does with Islamist terrorism and uses disproportionated defensive action against any Palestinian uprising. A sea of factors that converge in hatred and violence because both sides obstinately and collectively refuse to recognize and legitimate the existence of the other.

[Mondher Sfar, In search of the original Koran: the true history of the revealed text (New York: Prometheus Books, 2008) 152pp]

REVIEW / Marina G. Reina

Not much has been done regarding research about the authenticity of the Quranic text. This is something that Mondher Sfar has in mind throughout the book, that makes use of the scriptural techniques of the Koran, the scarce research material available, and the Islamic tradition, to redraw the erased story of the transmission of the holy book of Muslims. The same tradition that imposes “a representation of the revelation and of its textual product-which (…) is totally alien to the spirit and to the content of the Quranic text.”

The work is a sequencing of questions that arise from the gaps that the Islamic tradition leaves regarding the earliest testimony about the Koran and the biography of Prophet Muhammad. The result is an imprecise or inconclusive answer because it is almost impossible to trace the line back to the very early centuries of the existence of Islam, and due to an “insurmountable barrier” that “has been established against any historical and relativized perception of the Koran (…) to consecrate definitively the new orthodox ideology as the only possible and true one.”

As mentioned, Sfar’s main sources are those found in the tradition, by which we mean the records from notorious personalities in the early years of the religion. Their sayings prove “the existence in Muhammad’s time of two states of the revealed text: a first state and a reworked state that have been modified and corrected.” This fact “imperils the validity and identity of Revelation, even if its divine authenticity remains unquestioned.”

The synthesis that the author makes on the “kinds of division” (or alterations of the Revelation), reducing them to three from certain ayas in the Koran, is also of notorious interest. In short, these are “that of the modification of the text; that of satanic revelations; and finally, that of the ambiguous nature of the portion of the Revelation.” The first one exemplifies how the writing of the Revelation was changed along time; the second is grounded on a direct reference to this phenomenon in the Koran, when it says that “Satan threw some [false revelations] into his (Muhammad’s) recitation” (22:52), something that, by the way, is also mentioned in the Bible in Ezekiel 13:3, 6.

Another key point in the book is that of the components of the Koran (the surahs and the ayas) being either invented or disorganized later in time. The manuscripts of the “revealed text” vary in style and form, and the order of the verses was not definitively fixed until the Umayyad era. It is remarkable how something as basic as the titles of the surahs “does not figure in the first known Koranic manuscript”, nor was it reported by contemporaries to the Prophet to be ever mentioned by him. The same mystery arises upon the letters that can be read above at the beginning of the preambles in the surahs. According to the Tradition, they are part of the Revelation, whilst the author argues that they are linked to “the process of the formation of surahs”, as a way of numeration or as signatures from the scribes. As already mentioned, it is believed that the Koran version that we know today was made in two phases; in the second phase or correction phase surahs would have been added or divided. The writer remarks how a few surahs lack the common preambles and these characteristic letters, which leads to think that these elements were added in the proofreading part of the manuscript, so these organizational signals were omitted.

It may seem that at some points the author makes too many turns on the same topic (in fact, he even raises questions that remain unresolved throughout the book). Nonetheless, it is difficult to question those issues that have been downplayed from the Tradition and that, certainly, are weighty considerations that provide a completely different vision of what is known as the "spirit of the law.” This is precisely what he refers to by repeatedly naming the figure of the scribes of the Prophet, that “shaped” the divine word, “and it is this operation that later generations have tried to erase, in order to give a simplified and more-reassuring image of the Quranic message, that of a text composed by God in person,” instead of being “the product of a historical elaboration.”

What the author makes clear throughout the book is that the most significant and, therefore, most suspicious alterations of the Koran are those introduced by the first caliphs. Especially during the times of the third caliph, Uthman, the Koran was put on the agenda again, after years of being limited to a set of “sheets” that were not consulted. Uthman made copies of a certain “compilation” and “ordered the destruction of all the other existing copies.” Indeed, there is evidence of the existence of “other private collections” that belonged to dignitaries around the Prophet, of whose existence, Sfar notes that “around the fourth century of the Hijra, no trace was left.”

The author shows that the current conception of the Koran is rather simplistic and based on “several dogmas about, and mythical reconstructions of, the history.” Such is the case with the “myth of the literal ‘authenticity’,” which comes more “from apologetics than from the realm of historical truth.” This is tricky, especially when considering that the Koran is the result of a process of wahy (inspiration), not of a literal transcription, setting the differentiation between the Kitab (“the heavenly tablet”) and the Koran (“a liturgical lesson or a recitation”). Moreover, Sfar addresses the canonization of the Koran, which was made by Uthman, and which was criticized at its time for reducing the “several revelations without links between them, and that they were not designed to make up a book” into a single composition. This illustrates that “the principal star that dominated the period of prophetic revelation was to prove that the prophetic mission claimed by Muhammad was indeed authentic, and not to prove the literal authenticity of the divine message,” what is what the current Muslim schools of taught are inclined to support.

In general, although the main argument of the author suggests that the “Vulgate” version of the Koran might not be the original one, his other arguments lead the reader to deduce that this first manuscript does not vary a lot from the one we know today. Although it might seem so at first glance, the book is not a critique to the historicity of Islam or to the veracity of the Koran itself. It rather refers to the conservation and transmission thereof, which is one of the major claims in the Koran; of it being an honorable recitation in a well-guarded book (56:77-78). Perhaps, for those unfamiliar with the Muslim religion, this may seem insignificant. However, it is indeed a game-changer for the whole grounding of the faith. Muslims, the author says, remain ignorant of a lot of aspects of their religion because they do not go beyond the limits set by the scholars and religious authorities. It is the prevention from understanding the history that prevents from “better understanding the Koran” and, thus, the religion.

An update on the Iranian nuclear accord between 2018 and the resumed talks in April 2021

The signatories of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), reached in 2015 to limit Iran's nuclear program, met again on April 6 in Vienna to explore the possibility of reviving the accord. The US withdrawal after Donald Trump becoming president put the agreement on hold and lead Tehran to miss its commitments. Here we offer an update on the issue until the international talks resumed.

Trump's announcement of the US withdrawal from the JCPOA on May 8, 2018 [White House]

ARTICLE / Ana Salas Cuevas

The Islamic Republic of Iran is a key player in the stability of its regional environment, which means that it is a central country worth international attention. It is a regional power not only because of its strategic location, but also because of its large hydrocarbon reserves, which make Iran the fourth country in oil reserves and the second one in gas reserves.

In 2003, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) brought to the light and warned the international community about the existence of nuclear facilities, and of a covert program in Iran which could serve a military purpose. This prompted the United Nations and the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (the P5: France, China, Russia, the United States and the United Kingdom) to take measures against Iran in 2006. Multilateral and unilateral economic sanctions (the UN and the US) were implemented, which deteriorated Iran’s economy, but which did not stop its nuclear proliferation program. There were also sanctions linked to the development of ballistic missiles and to the support of terrorist groups. These sanctions, added to the ones the United States imposed on Tehran in the wake of the 1979 revolution, and together with the instability that cripples the country, caused a deep deterioration of Iran’s economy.

In November 2013, the P5 plus Germany (P5+1) and Iran came to terms with an initial agreement on Iran's nuclear program (a Joint Plan of Action) which, after several negotiations, translated in a final pact, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed in 2015. The European Union adhered to the JCPOA.

The focus of Iran's motives for succumbing and accepting restrictions on its nuclear program lies in the Iranian regime’s concern that the deteriorating living conditions of the Iranian population due to the economic sanctions could result in growing social unrest.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action

The goal of these negotiations was to reach a long-term comprehensive solution agreed by both parties to ensure that Iran´s nuclear program would be completely peaceful. Iran reiterated that it would not seek or develop any nuclear weapons under any circumstances. The real aim of the nuclear deal, though, was to extend the time needed for Iran to produce enough fissile material for bombs from three months to one year. To this end, a number of restrictions were reached.

This comprehensive solution involved a mutually defined enrichment plan with practical restrictions and transparent measures to ensure the peaceful nature of the program. In addition, the resolution incorporated a step-by-step process of reciprocity that included the lifting of all UN Security Council, multilateral and national sanctions related to Iran´s nuclear program. In total, these obligations were key to freeze Iran’s nuclear program and reduced the factors most sensitive to proliferation. In return, Iran received limited sanctions relief.

More specifically, the key points in the JCPOA were the following: Firstly, for 15 years, Iran would limit its uranium enrichment to 3.67%, eliminate 98% of its enriched uranium stocks in order to reduce them to 300 kg, and restrict its uranium enrichment activities to its facilities at Natanz. Secondly, for 10 years, it would not be able to operate more than 5,060 old and inefficient IR-1 centrifuges to enrich uranium. Finally, inspectors from the IAEA would be responsible for the next 15 years for ensuring that Iran complied with the terms of the agreement and did not develop a covert nuclear program.

In exchange, the sanctions imposed by the United States, the European Union and the United Nations on its nuclear program would be lifted, although this would not apply to other types of sanctions. Thus, as far as the EU is concerned, restrictive measures against individuals and entities responsible for human rights violations, and the embargo on arms and ballistic missiles to Iran would be maintained. In turn, the United States undertook to lift the secondary sanctions, so that the primary sanctions, which have been in place since the Iranian revolution, remained unchanged.

To oversee the implementation of the agreement, a joint committee composed of Iran and the other signatories to the JCPOA would be established to meet every three months in Vienna, Geneva or New York.

United States withdrawal

In 2018, President Trump withdrew the US from the 2015 Iran deal and moved to resume the sanctions lifted after the agreement was signed. The withdrawal was accompanied by measures that could pit the parties against each other in terms of sanctions, encourage further proliferation measures by Iran and undermine regional stability. The US exit from the agreement put the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action on hold.

The United States argued that the agreement allowed Iran to approach the nuclear threshold in a short period of time. With the withdrawal, however, the US risked bringing this point closer in time by not waiting to see what could happen after the 10 and 15 years, assuming that the pact would not last after that time. This may make Iran's proliferation a closer possibility.

Shortly after Trump announced the first anniversary of its withdrawal from the nuclear deal and the assassination of powerful military commander Qasem Soleimani by US drones, Iran announced a new nuclear enrichment program as a signal to nationalists, designed to demonstrate the power of the mullah regime. This leaves the entire international community to question whether diplomatic efforts are seen in Tehran as a sign of weakness, which could be met with aggression.

On the one hand, some opinions consider that, by remaining within the JCPOA, renouncing proliferation options and respecting its commitments, Iran gains credibility as an international actor while the US loses it, since the agreements on proliferation that are negotiated have no guarantee of being ratified by the US Congress, making their implementation dependent on presidential discretion.

On the other hand, the nuclear agreement adopted in 2015 raised relevant issues from the perspective of international law. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action timeline is 10 to 15 years. This would terminate restrictions on Iranian activities and most of the verification and control provisions would expire. Iran would then be able to expand its nuclear facilities and would find it easier to develop nuclear weapons activities again. In addition, the legal nature of the Plan and the binding or non-binding nature of the commitments made under it have been the subject of intense debate and analysis in the United States. The JCPOA does not constitute an international treaty. So, if the JCPOA was considered to be a non-binding agreement, from the perspective of international law there would be no obstacle for the US administration to withdraw from it and reinstate the sanctions previously adopted by the United States.

The JCPOA after 2018

As mentioned, the agreement has been held in abeyance since 2018 because the IAEA inspectors in Vienna will no longer have access to Iranian facilities.

Nowadays, one of the factors that have raised questions about Iran’s nuclear documents is the IAEA’s growing attention to Tehran’s nuclear contempt. In March 2020, the IAEA “identified a number of questions related to possible undeclared nuclear material and nuclear-related activities at three locations in Iran”. The agency’s Director General Rafael Grossi stated: “The fact that we found traces (of uranium) is very important. That means there is the possibility of nuclear activities and material that are not under international supervision and about which we know not the origin or the intent”.

The IAEA also revealed that the Iranian regime was violating all the restrictions of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. The Iranian leader argued that the US first violated the terms of the JCPOA when it unilaterally withdrew the terms of the JCPOA in 2018 to prove its reason for violating the nuclear agreement.

In the face of the economic crisis, the country has been hit again by the recent sanctions imposed by the United States. Tehran ignores the international community and tries to get through the signatory countries of the agreement, especially the United States, claiming that if they return to compliance with their obligations, Iran will also quickly return to compliance with the treaty. This approach has put strong pressure on the new US government from the beginning. Joe Biden's advisors suggested that the agreement could be considered again. But if Washington is faced with Tehran's full violation of the treaty, it will be difficult to defend such a return to the JCPOA.

In order to maintain world security, the international community must not succumb to Iran’s warnings. Tehran has long issued empty threats to force the world to accept its demands. For example, in January 2020, when the UK, France and Germany triggered the JCPOA’s dispute settlement mechanism, the Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a direct warning, saying: “If Europeans, instead of keeping to their commitments and making Iran benefit from the lifting of sanctions, misuse the dispute resolution mechanism, they’ll need to be prepared for the consequences that they have been informed about earlier”.

Conclusions

The purpose of the agreement is to prevent Iran from becoming a nuclear power that would exert pressure on neighboring countries and further destabilize the region. For example, Tehran's military influence is already keeping the war going in Syria and hampering international peace efforts. A nuclear Iran is a frightening sight in the West.

The rising in tensions between Iran and the United States since the latter unilaterally abandoned the JCPOA has increased the deep mistrust already separating both countries. Under such conditions, a return to the JCPOA as it was before 2018 seems hardly imaginable. A renovated agreement, however, is baldly needed to limit the possibilities of proliferation in an already too instable region. Will that be possible?

El refuerzo económico catarí y la ampliación de sus relaciones con Rusia, China y Turquía restaron eficacia al bloqueo que le habían impuesto sus vecinos del Golfo

Es una realidad: Catar ha vencido en su pulso contra Emiratos Árabes Unidos y Arabia Saudí tras más de tres años de ruptura diplomática en los que ambos países, junto con otros vecinos árabes, aislaron comercial y territorialmente a la península catarí. Razones económicas y de configuración geopolítica explican que el bloqueo impuesto finalmente se haya desvanecido sin que Catar haya cedido en su línea diplomática autónoma.

El emir de Catar, Tamim Al Thani, en la Conferencia de Seguridad de Múnich de 2018 [Kuhlmann/MSC]

ARTÍCULO / Sebastián Bruzzone

En junio de 2017, Egipto, Jordania, Arabia Saudí, Bahréin, Emiratos Árabes Unidos, Libia, Yemen y Maldivas acusaron a la familia Al Thani de apoyar el terrorismo islámico y a los Hermanos Musulmanes e iniciaron un bloqueo total al comercio con origen y destino en Catar hasta que Doha cumpliera con trece condiciones. Sin embargo, el pasado 5 de enero de 2021, el príncipe heredero de Arabia Saudí, Mohammed bin Salman, recibió al emir de Catar, Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, con un inesperado abrazo en la ciudad saudí de Al-Ula, sellando el final de un capítulo oscuro más de la historia moderna del Golfo Pérsico. Pero, ¿cuántas de las trece exigencias ha cumplido Catar para reconciliarse con sus vecinos? Ninguna.

Como si nada hubiera pasado. Tamim Al Thani llegó a Arabia Saudí para participar en la 41º Cumbre del Consejo de Cooperación del Golfo (CCG) en la que los estados miembros se comprometieron a realizar esfuerzos para fomentar la solidaridad, la estabilidad y el multilateralismo ante los desafíos de la región, que se enfrenta al programa nuclear y de misiles balísticos de Irán, así como a sus planes de sabotaje y destrucción. Además, el CCG en su conjunto agradeció el papel mediador de Kuwait, del entonces presidente estadounidense Donald J. Trump y de su yerno, Jared Kushner.

La reunión de los líderes árabes del Golfo ha sido el deshielo en el desierto político tras una tormenta de acusaciones mutuas e inestabilidad en lo que se denominó “crisis diplomática de Catar”; ese acercamiento, como efecto inmediato, despeja la normal preparación de la Copa del Mundo de fútbol prevista en Catar para el próximo año. Siempre es positivo el retorno del entendimiento regional y diplomático en situaciones de urgencia como una crisis económica, una pandemia mundial o un enemigo común chiíta armando misiles en la otra orilla del mar. En todo caso, el Catar de los Al Thani puede coronarse como el vencedor del pulso económico frente a los emiratíes Al Nahyan y los saudíes Al Saud incapaces de asfixiar a la pequeña península.

Los factores

La pregunta relevante nos devuelve al título inicial previo a estas líneas: ¿cómo Catar ha conseguido resistir la presión sin doblegarse lo más mínimo frente a las trece condiciones exigidas en 2017? Varios factores contribuyen a explicarlo.

Primero, la inyección de capital por QIA (Qatar Investment Authority). A principios del bloqueo, el sistema bancario sufrió una fuga de capitales de más de 30.000 millones de dólares y la inversión extranjera disminuyó notablemente. El fondo soberano catarí respondió ingresando 38.500 millones de dólares para proveer de liquidez a los bancos y reactivar la economía. El bloqueo comercial repentino de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos y Arabia Saudí supuso una espantada financiera que llevó a inversores extranjeros, e incluso residentes cataríes, a transferir sus activos fuera del país y liquidar sus posiciones ante el miedo a un colapso del mercado.

Segundo, el acercamiento a Turquía. En 2018, Catar salió al rescate de Turquía comprometiéndose a invertir 15.000 millones de dólares en activos turcos de todo tipo y, en 2020, a ejecutar un acuerdo de permuta o swap de divisas con el fin de elevar el valor de la lira turca. En reciprocidad, Turquía aumentó en un 29% la exportación de productos básicos a Catar e incrementó la presencia militar en la península catarí frente a una posible invasión o ataque de sus vecinos, construyendo una segunda base militar turca cerca de Doha. Además, como medida de refuerzo interna, el gobierno catarí ha invertido más de 30.000 millones de dólares en equipamiento militar, artillería, submarinos y aviones de empresas americanas.

Tercero, la aproximación a Irán. Catar comparte con el país persa el yacimiento de gas South Pars North Dome, considerado el más grande del mundo, y se posicionó como mediador entre la Administración Trump y el gobierno ayatolá. Desde 2017, Irán ha suministrado 100.000 toneladas diarias de alimentos a Doha ante una posible crisis alimenticia causada por el bloqueo de la única frontera terrestre con Arabia Saudí por la que entraba el 40% de los alimentos.

Cuarto, el acercamiento a Rusia y China. El fondo soberano catarí adquirió el 19% del accionariado de Rosneft, abriendo las puertas a la colaboración entre la petrolera rusa y Qatar Petroleum y a más joint ventures empresariales entre ambas naciones. En la misma línea, Qatar Airways aumentó su participación hasta el 5% del capital de China Southern Airlines.

Quinto, su refuerzo como primer exportador mundial de GNL (Gas Natural Licuado). Es importante saber que el principal motor económico de Catar es el gas, no el petróleo. Por ello, en 2020, el gobierno catarí inició su plan de expansión aprobando una inversión de 50.000 millones de dólares para ampliar su capacidad de licuefacción y de transporte con buques metaneros, y otra de 29.000 millones de dólares para construir más plataformas marítimas extractoras en North Dome. El gobierno catarí ha previsto que su producción de GNL crecerá un 40% para 2027, pasando de 77 a 110 millones toneladas anuales.

Debemos tener en cuenta que el transporte de GNL es mucho más seguro, limpio, ecológico y barato que el transporte del petróleo. Además, la Royal Dutch Shell vaticinó en su informe “Annual LNG Outlook Report 2019” que la demanda mundial de GNL se duplicaría para 2040. De confirmarse este pronóstico, Catar estaría a las puertas de un impresionante crecimiento económico en las próximas décadas. Por lo tanto, lo que más le conviene en esa situación es mantener sus arcas públicas solventes y un clima político estable en la región de Oriente Medio. Por si fuera poco, el pasado noviembre de 2020, Tamim Al Thani anunció que los presupuestos estatales futuros se configurarán en base a un precio ficticio de 40 dólares por barril, un valor bastante más pequeño que el WTI Oil Barrel o Brent Oil Barrel que se encuentra en torno a 60-70 dólares. Es decir, el gobierno catarí indexará su gasto público considerando la volatilidad de los precios de los hidrocarburos. En otras palabras, Catar busca ser previsor frente a un posible desplome del precio del crudo, impulsando una política de gasto público eficiente.

Y sexto, el mantenimiento del portafolio de inversiones de Qatar Investment Authority, valorado en 300.000 millones de dólares. Los activos del fondo soberano catarí constituyen un seguro de vida para el país que puede ordenar su liquidación en situaciones de necesidad extrema.

Catar tiene un papel muy importante para el futuro del Golfo Pérsico. La dinastía Al Thani ha demostrado su capacidad de gestión política y económica y, sobre todo, su gran previsión a futuro frente al resto de países del Consejo de Cooperación del Golfo. La pequeña “perla” peninsular ha dado un golpe sobre la mesa imponiéndose sobre el príncipe heredero de Arabia Saudí, Mohammed bin Salman, y sobre el príncipe heredero de Abu Dhabi, Mohammed bin Zayed, que ni se presentó en Al-Ula. Este movimiento geopolítico, más la decisión de la Administración Biden de mantener la política de línea dura frente a Irán, parece garantizar el aislamiento internacional del régimen ayatolá del país persa.

IDF soldiers during a study tour as part of Sunday culture, at the Ramon Crater Visitor Center [IDF]

ESSAY / Jairo Císcar

The geopolitical reality that exists in the Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean is incredibly complex, and within it the Arab-Israeli conflict stands out. If we pay attention to History, we can see that it is by no means a new conflict (outside its form): it can be traced back to more than 3,100 years ago. It is a land that has been permanently disputed; despite being the vast majority of it desert and very hostile to humans, it has been coveted and settled by multiple peoples and civilizations. The disputed territory, which stretches across what today is Israel, Palestine, and parts of Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, and Syria practically coincides with historic Canaan, the Promised Land of the Jewish people. Since those days, the control and prevalence of human groups over the territory was linked to military superiority, as the conflict was always latent. The presence of military, violence and conflict has been a constant aspect of societies established in the area; and, with geography and history, is fundamental to understand the current conflict and the functioning of the Israeli society.

As we have said, a priori it does not have great reasons for a fierce fight for the territory, but the reality is different: the disputed area is one of the key places in the geostrategy of the western and eastern world. This thin strip, between the Tigris and Euphrates (the Fertile Crescent, considered the cradle of the first civilizations) and the mouth of the Nile, although it does not enjoy great water or natural resources, is an area of high strategic value: it acts as a bridge between Africa, Asia and the Mediterranean (with Europe by sea). It is also a sacred place for the three great monotheistic religions of the world, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, the “Peoples of the Book”, who group under their creeds more than half of the world's inhabitants. Thus, for millennia, the land of Israel has been abuzz with cultural and religious exchanges ... and of course, struggles for its control.

According to the Bible, the main para-historical account of these events, the first Israelites began to arrive in the Canaanite lands around 2000 BC, after God promised Abraham that land “... To your descendants ...”[1] The massive arrival of Israelites would occur around 1400 BC, where they started a series of campaigns and expelled or assimilated the various Canaanite peoples such as the Philistines (of which the Palestinians claim to be descendants), until the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah finally united around the year 1000 BC under a monarchy that would come to dominate the region until their separation in 924 BC.

It is at this time that we can begin to speak of a people of Israel, who will inhabit this land uninterruptedly, under the rule of other great empires such as the Assyrian, the Babylonian, and the Macedonian, to finally end their existence under the Roman Empire. It is in 63 BC when Pompey conquered Jerusalem and occupied Judea, ending the freedom of the people of Israel. It will be in 70 AD, though, with the emperor Titus, when after a new Hebrew uprising the Second Temple of Jerusalem was razed, and the Diaspora of the Hebrew people began; that is, their emigration to other places across the East and West, living in small communities in which, suffering constant persecutions, they continued with their minds set on a future return to their “Promised Land”. The population vacuum left by the Diaspora was then filled again by peoples present in the area, as well as by Arabs.

The current state of Israel

This review of the historical antiquity of the conflict is necessary because this is one with some very special characteristics: practically no other conflict is justified before such extremes by both parties with “sentimental” or dubious “legal” reasons.

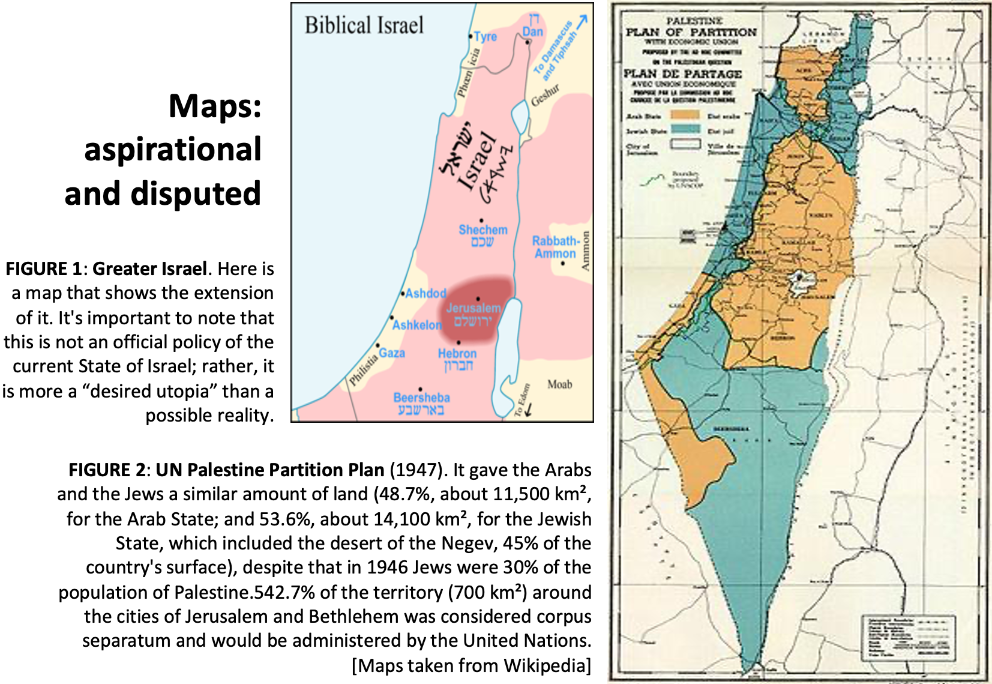

The current state of Israel, founded in 1948 with the partition of the British Protectorate of Palestine, argues its existence in the need for a Jewish state that not only represents and welcomes such a community but also meets its own religious requirements, since in Judaism the Hebrew is spoken as the “chosen people of God”, and Israel as its “Promised Land”. So, being the state of Israel the direct heir of the ancient Hebrew people, it would become the legitimate occupier of the lands quoted in Genesis 15: 18-21. This is known as the concept of Greater Israel (see map)[2].

On the Palestinian side, they exhibit as their main argument thirteen centuries of Muslim rule (638-1920) over the region of Palestine, from the Orthodox caliphate to the Ottoman Empire. They claim that the Jewish presence in the region is primarily based on the massive immigration of Jews during the late 19th and 20th centuries, following the popularization of Zionism, as well as on the expulsion of more than 700,000 Palestinians before, during and after the Arab-Israeli war of 1948, a fact known as the Nakba[3], and of many other Palestinians and Muslims in general since the beginning of the conflict. Some also base their historical claim on their origin as descendants of the Philistines.

However, although these arguments are weak, beyond historical conjecture, the reality is, nonetheless, that these aspirations have been the ones that have provoked the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. This properly begins in the early 20th century, with the rise of Zionism in response to the growing anti-Semitism in Europe, and the Arab refusal to see Jews settled in the area of Palestine. During the years of the British Mandate for Palestine (1920-1948) there were the first episodes of great violence between Jews and Palestinians. Small terrorist actions by the Arabs against Kibbutzim, which were contested by Zionist organizations, became the daily norm. This turned into a spiral of violence and assassinations, with brutal episodes such as the Buraq and Hebron revolts, which ended with some 200 Jews killed by Arabs, and some 120 Arabs killed by the British army.[4]

Another dark episode of this time was the complicit relations between the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Almin Al-Husseini, and the Nazi regime, united by a common agenda regarding Jews. He had meetings with Adolf Hitler and gave them mutual support, as the extracts of their conversations collect[5]. But it will not be until the adoption of the “United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine” through Resolution 181 (II) of the General Assembly when the war broke out on a large scale.[6] The Jews accepted the plan, but the Arab League announced that, if it became effective, they would not hesitate to invade the territory.

And so, it was. On May 14, 1948, hours after the proclamation of the state of Israel by Ben-Gurion, Israel was invaded by a joint force of Egyptian, Iraqi, Lebanese, Syrian and Jordanian troops. In this way, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War began, beginning a period of war that has not stopped until today, almost 72 years later. Despite the multiple peace agreements reached (with Egypt and Jordan), the dozens of United Nations resolutions, and the Oslo Accords, which established the roadmap for achieving a lasting peace between Israel and Palestine, conflicts continue, and they have seriously affected the development of the societies and peoples of the region.

The Israel Defense Forces

Despite the difficulties suffered since the day of its independence, Israel has managed to establish itself as the only effective democracy in the region, with a strong rule of law and a welfare state. It has a Human Development Index of 0.906, considered very high; is an example in education and development, being the third country in the world with more university graduates over the total population (20%) and is a world leader in R&D in technology. Meanwhile, the countries around it face serious difficulties, and in the case of Palestine, great misery. One of the keys to Israel's success and survival is, without a doubt, its Army. Without it, it would not have been able to lay the foundations of the country that it is today, as it would have been devastated by neighboring countries from the first day of its independence.

It is not daring to say that Israeli society is one of the most militarized in the world. It is even difficult to distinguish between Israel as a country or Israel as an army. There is no doubt that the structure of the country is based on the Army and on the concept of “one people”. The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) act as the backbone of society and we find an overwhelming part of the country's top officials who have served as active soldiers. The paradigmatic example are the current leaders of the two main Knesset parties: Benny Ganz (former Chief of Staff of the IDF) and Benjamin Netanyahu (a veteran of the special forces in the 1970s, and combat wounded).

This influence exerted by the Tzahal[7] in the country is fundamentally due to three reasons. The first is the reality of war. Although, as we have previously commented, Israel is a prosperous country and practically equal to the rest of the western world, it lives in a reality of permanent conflict, both inside and outside its borders. When it is not carrying out large anti-terrorist operations such as Operation “Protective Edge,” carried out in Gaza in 2014, it is in an internal fight against attacks by lone wolves (especially bloody recent episodes of knife attacks on Israeli civilians and military) and against rocket and missile launches from the Gaza Strip. The Israeli population has become accustomed to the sound of missile alarms, and to seeing the “Iron Dome” anti-missile system in operation. It is common for all houses to have small air raid shelters, as well as in public buildings and schools. In them, students learn how to behave in the face of an attack and basic security measures. The vision of the Army on the street is something completely common, whether it be armored vehicles rolling through the streets, fighters flying over the sky, or platoons of soldiers getting on the public bus with their full equipment. At this point, we must not forget the suffering in which the Palestinian population constantly lives, as well as its harsh living conditions, motivated not only by the Israeli blockade, but also by living under the government of political parties such as Al-Fatah or Hamas. The reality of war is especially present in the territories under dispute with other countries: the Golan Heights in Syria and the so-called Palestinian Territories (the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip). Military operations and clashes with insurgents are practically daily in these areas.

This permanent tension and the reality of war not only affect the population indirectly, but also directly with compulsory military service. Israel is the developed country that spends the most defense budget according to its GDP and its population.[8] Today, Israel invests 4.3% of its GDP in defense (not counting investment in industry and military R&D).[9] In the early 1980s, it came to invest around 22%. Its army has 670,000 soldiers, of whom 170,000 are professionals, and 35.9% of its population (just over 3 million) are ready for combat. It is estimated that the country can carry out a general mobilization around 48-72 hours. Its military strength is based not only on its technological vanguard in terms of weapons systems such as the F-35 (and atomic arsenal), material, armored vehicles (like the Merkava MBT), but also on its compulsory military service system that keeps the majority of the population trained to defend its country. Israel has a unique military service in the western world, being compulsory for all those over 18 years of age, be they men or women. In the case of men, it lasts 32 months, while women remain under military discipline for 21 months, although those that are framed in combat units usually serve the same time as men. Military service has exceptions, such as Arabs who do not want to serve and ultra-Orthodox Jews. However, more and more Israeli Arabs serve in the armed forces, including in mixed units with Druze, Jews and Christians; the same goes for the ultra-orthodox, who are beginning to serve in units adapted to their religious needs. Citizens who complete military service remain in the reserve until they are 40 years old, although it is estimated that only a quarter of them do so actively.[10]

Social cohesion

Israeli military service and, by extension, the Israeli Defense Forces are, therefore, the greatest factor of social cohesion in the country, above even religion. This is the second reason why the army influences Israel. The experience of a country protection service carried out by all generations creates great social cohesion. In the Israeli mindset, serving in the military, protecting your family and ensuring the survival of the state is one of the greatest aspirations in life. From the school, within the academic curriculum itself, the idea of patriotism and service to the nation is integrated. And right now, despite huge contrasts between the Jewish majority and minorities, it is also a tool for social integration for Arabs, Druze and Christians. Despite racism and general mistrust towards Arabs, if you serve in the Armed Forces, the reality changes completely: you are respected, you integrate more easily into social life, and your opportunities for work and study after the enlistment period have increased considerably. Mixed units, such as Unit 585 where Bedouins and Christian Arabs serve,[11] allow these minorities to continue to throw down barriers in Israeli society, although on many occasions they find rejection from their own communities.

Israelis residing abroad are also called to service, after which many permanently settle in the country. This enhances the sense of community even for Jews still in the Diaspora.

In short, the IDF creates a sense of duty and belonging to the homeland, whatever the origin, as well as a strong link with the armed forces (which is hardly seen in other western countries) and acceptance of the sacrifices that must be made in order to ensure the survival of the country.

The third and last reason, the most important one, and the one that summarizes the role that the Army has in society and in the country, is the reality that, as said above, the survival of the country depends on the Army. This is how the military occupation of territories beyond the borders established in 1948, the bombings in civilian areas, the elimination of individual objectives are justified by the population and the Government. After 3,000 years, and since 1948 perhaps more than ever, the Israeli people depend on weapons to create a protection zone around them, and after the persecution throughout the centuries culminating in the Holocaust and its return to the “Promised Land,” neither the state nor the majority of the population are willing to yield in their security against countries or organizations that directly threaten the existence of Israel as a country. This is why despite the multiple truces and the will (political and real) to end the Arab-Israeli conflict, the country cannot afford to step back in terms of preparing its armed forces and lobbying.

Obviously, during the current Covid-19 pandemic, the Army is having a key role in the success of the country in fighting the virus. The current rate of vaccination (near 70 doses per 100 people) is boosted by the use of reserve medics from the Army, as well as the logistic experience and planning (among obviously many other factors). Also, they have provided thousands of contact tracers, and the construction of hundreds of vaccination posts, and dozens of quarantine facilities. Even could be arguable that the military training could play a role in coping with the harsh restrictions that were imposed in the country.

The State-Army-People trinity exemplifies the reality that Israel lives, where the Army has a fundamental (and difficult) role in society. It is difficult to foresee a change in reality in the near future, but without a doubt, the army will continue to have the leadership role that it has assumed, in different forms, for 3,000 years.

[1] Genesis 15:18 New International Version (NIV). 18: “On that day the Lord made a covenant with Abram and said, ‘To your descendants I give this land, from the Wadi [a] of Egypt to the great river, the Euphrates’.”

[2] Great Israel matches to previously mentioned Bible passage Gn. 15: 18-21.

[3] Independent, JS (2019, May 16). This is why Palestinians wave keys during the 'Day of Catastrophe'. Retrieved March 23, 2020, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/nakba-day-catastrophe-palestinians-israel-benjamin-netanyahu-gaza-west-bank-hamas-a8346156.html

[4] Ross Stewart (2004). Causes and Consequences of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. London: Evan Brothers, Ltd., 2004.

[5] Record of the Conversation Between the Führer and the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem on November 28, 1941, in in Berlin, Documents on German Foreign Policy, 1918-1945, Series D, Vol. XIII, London , 1964, p. 881ff, in Walter Lacquer and Barry Rubin, The Israel-Arab Reader, (NY: Facts on File, 1984), pp. 79-84. Retrieved from https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-mufti-and-the-f-uuml-hrer#2. “Germany stood for uncompromising war against the Jews. That naturally included active opposition to the Jewish national home in Palestine .... Germany would furnish positive and practical aid to the Arabs involved in the same struggle .... Germany's objective [is] ... solely the destruction of the Jewish element residing in the Arab sphere .... In that hour the Mufti would be the most authoritative spokesman for the Arab world. The Mufti thanked Hitler profusely. ”

[6] United Nations General Assembly A / RES / 181 (II) of 29 November 1947.

[7] Tzahal is a Hebrew acronym used to refer to the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).

[8] Newsroom. (8th. June 2009). Arming Up: The world's biggest military spenders by population. 03-20-2020, by The Economist Retrieved from: https://www.economist.com/news/2009/06/08/arming-up

[9] Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. (nd). SIPRI Military Expenditure Database. Retrieved March 21, 2020, from https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex

[10] Gross, JA (2016, May 30). Just a quarter of all eligible reservists serve in the IDF. Retrieved March 22, 2020, from https://www.timesofisrael.com/just-a-quarter-of-all-eligible-reservists-serve-in-the-idf/

[11] AHRONHEIM, A. (2020, January 12). Arab Christians and Bedouins in the IDF: Meet the members of Unit 585. Retrieved March 19, 2020, from https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/The-sky-is-the-limit-in-the- IDFs-unique-Unit-585-613948

The wave of diplomatic recognition of Israel by some Arab countries constitutes a shift in regional alliances

![Dubai, the largest city in the United Arab Emirates [Pixabay] Dubai, the largest city in the United Arab Emirates [Pixabay]](/documents/16800098/0/acuerdos-abraham-blog.jpg/43eef7ab-96b1-fcd7-b19d-4d682361590c?t=1621884303752&imagePreview=1)

▲ Dubai, the largest city in the United Arab Emirates [Pixabay]

ANALYSIS / Ann M. Callahan

With the signing of the Abraham Accords, seven decades of enmity between the states were concluded. With a pronounced shift in regional alliances and a convergence of interests crossing traditional alignments, the agreements can be seen as a product of these regional changes, commencing a new era of Arab-Israeli relations and cooperation. While the historic peace accords seem to present a net positive for the region, it would be a mistake to not take into consideration the losing party in the deal; the Palestinians. It would also be a error to dismiss the passion with which many people still view the Palestinian issue and the apparent disconnect between the Arab ruling class and populace.

On the 15th of September, 2020, a joint peace deal was signed between the State of Israel, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and the United States, known also as the Abraham Accords Peace Agreement. The Accords concern a treaty of peace, and a full normalization of the diplomatic relations between the United Emirates and the State of Israel. The United Arab Emirates stands as the first Persian Gulf state to normalize relations with Israel, and the third Arab state, after Egypt in 1979 and Jordan in 1994. The deal was signed in Washington on September 15 by the UAE’s Foreign Minister Abdullah bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan and the Prime Minister of the State of Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu. It was accepted by the Israeli cabinet on the 12th of October and was ratified by the Knesset (Israel’s unicameral parliament) on the 15th of October. The parliament and cabinet of the United Arab Emirates ratified the agreement on the 19th of October. On the same day, Bahrain confirmed its pact with Israel through the Accords, officially called the Abraham Accords: Declaration of Peace, Cooperation, and Constructive Diplomatic and Friendly Relations. Signed by Bahrain’s Foreign Minister Abdullatif bin Rashid Al Zayani and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the President of the United States Donald Trump as a witness, the ratification indicates an agreement between the signatories to commence an era of alliance and cooperation towards a more stable, prosperous and secure region. The proclamation acknowledges each state's sovereignty and agrees towards a reciprocal opening of embassies and as well as stating intent to seek out consensus regarding further relations including investment, security, tourism and direct flights, technology, healthcare and environmental concerns.

The United States played a significant role in the accords, brokering the newly signed agreements. President of the United States, Donald Trump, pushed for the agreements, encouraging the relations and negotiations and promoting the accords, and hosting the signing at the White House.

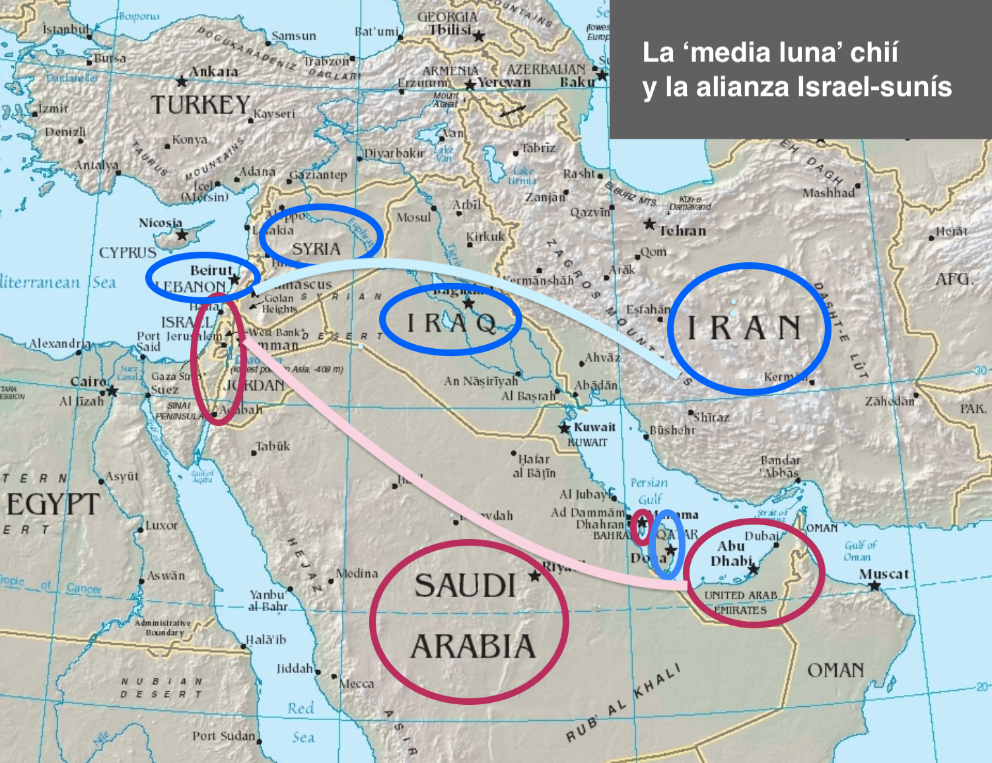

As none of the countries involved in the Abraham Accords had ever fought against each other, these new peace deals are not of the same weight or nature as Egypt’s peace deal with Israel in 1979. Nevertheless, the accords are much more than a formalizing of what already existed. Now, whether or not the governments collaborated in secret concerning security and intelligence previously, they will now cooperate publicly through the aforementioned areas. For Israel, Bahrain and the UAE, the agreements pave a path for the increase of trade, investment, tourism and technological collaboration. In addition to these gains, a strategic alliance against Iran is a key motivator as the two states and the U.S. regard Iran as the chief threat to the region’s stability.

Rationale

What was the rationale for this diplomatic breakthrough and what prompted it to take place this year? It could be considered to be a product of the confluence of several pivotal impetuses.

The accords are seen as a product of a long-term trajectory and a regional reality where over the course of the last decade Arab states, particularly around the Gulf, have begun to shift their priorities. The UAE, Bahrain and Israel had found themselves on the same side of more than one major fissure in the Middle East. These states have also sided with Israel regarding Iran. Saudi Arabia, too, sees Shiite Iran as a major threat, and while, as of now, it has not formalized relations with Israel, it does have ties with the Hebrew state. This opposition to Tehran is shifting alliances in the region and bringing about a strategic realignment of Middle Eastern powers.

Furthermore, opposition to the Sunni Islamic extremist groups presents a major threat to all parties involved. The newly aligned states all object to Turkey’s destabilizing support of the Muslim Brotherhood and its proxies in the regional conflicts in Gaza, Libya and Syria. Indeed, the signatories’ combined fear of transnational jihadi movements, such as Al-Qaeda and ISIS derivatives, has aligned their interests closer to each other.

In addition, there has been a growing frustration and fatigue with the Palestinian Cause, one which could seem interminable. A certain amount of patience has been lost and Arab nations that had previously held to the Palestinian cause have begun to follow their own national interests. Looking back to late 2017, when the Trump administration officially recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, had it been a decade earlier there would have been widespread protests and resulting backlash from the regional leaders in response, however it was not the case. Indeed, there was minimal criticism. This may indicate that, at least for the regional leaders, that adherence to the Palestinian cause is lessening in general.

The prospects of closer relations with the economically vibrant state of Israel, and by extension with that of the United States is increasingly attractive to many Arab states. Indeed, expectations of an arms sale of U.S. weapon systems to the UAE, while not written specifically into the accords, is expected to come to pass through a side agreement currently under review by Congress.

From the perspective of Israel, the country has gone through a long political crisis with, in just one year alone, three national elections. In the context of these domestic efforts, prime minister Netanyahu raised propositions of annexing more sections of the contended West Bank. Consequently, the UAE campaigned against it and Washington called for Israel to choose between prospects of annexation or normalization. The normalization was concluded in return for suspending the annexation plans. There is debate regarding whether or not the suspending of the plans are something temporary or a permanent cessation of the annexation. There is a discrepancy between the English and Arabic versions of the joint treaty. The English version declared that the accord “led to the suspension of Israel’s plans to extend its sovereignty.” This differs slightly, however significantly, from the Arabic copy in which “[the agreement] has led to Israel’s plans to annex Palestinian lands being stopped.” This inconsistency did not go unnoticed to the party most affected; the Palestinians. There is a significant disparity between a temporary suspension as opposed to a complete stopping of annexation plans.

For Netanyahu, being a leading figure in a historic peace deal bringing Israel even more out of its isolation without significant concessions would certainly boost his political standing in Israel. After all, since Israel's creation, what it has been longing for is recognition, particularly from its Arab neighbors.

Somewhat similarly to Netanyahu, the Trump Administration had only to gain through the concluding of the Accords. The significant accomplishment of a historic peace deal in the Middle East was certainly a benefit especially leading up to the presidential elections, the which took place earlier this November. On analyzing the Administration’s approach towards the Middle East, its strategy clearly encouraged the regional realignment and the cultivation of the Gulf states’ and Israel’s common interests, culminating in the joint accords.

Implications

As a whole, the Abraham Accords seem to have broken the traditional alignment of Arab States in the Middle East. The fact that normalization with Israel has been achieved without a solution to the Palestinian issue is indicative of the shift in trends among Arab nations which were previously staunchly adherent to the Palestinian cause. Already, even Sudan, a state with a violent past with Israel, has officially expressed its consent to work towards such an agreement. Potentially, other Arab states are thought to possibly follow suit in future normalization with Israel.

Unlike Bahrain and the UAE, Sudan has sent troops to fight against Israel in the Arab-Israeli wars. However, following the UAE and Bahrain accords, a Sudan-Israel normalization agreement transpired on October 23rd, 2020. While it is not clear if the agreement solidifies full diplomatic relations, it promotes the normalization of relations between the two countries. Following the announcement of their agreement, the designated foreign minister, Omar Qamar al-Din, clarified that the agreement with Israel was not actually a normalization, rather an agreement to work towards normalization in the future. It is only a preliminary agreement as it requires the approval of an elected parliament before going into force. Regardless, the agreement is a significant step for Sudan as it had previously considered Israel an enemy of the state.

While clandestine relations between Israel and the Gulf states were existent for years, the founding of open relations is a monumental shift. For Israel, putting aside its annexation plans was insignificant in comparison with the many advantages of the Abraham Accords. Contrary to what many expected, no vast concessions were to be made in return for the recognition of sovereignty and establishment of diplomatic ties for which Israel yearns for. In addition, Israel is projected to benefit economically from its new forged relations with the Gulf states between the increased tourism, direct flights, technology and information exchange, commercial relations and investment. Already, following the Accord’s commitment, the US, Israel and the UAE have already established the Abraham Fund. Through the program more than $3 billion dollars will be mobilized in the private sector-led development strategies and investment ventures to promote economic cooperation and profitability in the Middle East region through the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, Israel and the UAE.

The benefits of the accords extend to a variety of areas in the Arab world including, most significantly, possible access to U.S. defense systems. The prospect of the UAE receiving America’s prestigious F-35 systems is in fact underway. President Trump, at least, is willing to make the sale. However, it has to pass through Congress which has been consistently dedicated to maintaining Israel’s qualitative military edge in the region. According to the Senate leader Mitch McConnell (Rep, KY), “We in congress have an obligation to review any U.S. arm sale package linked to the deal [...] As we help our Arab partners defend against growing threats, we must continue ensuring that Israel’s qualitative military edge remains unchallenged.” Should the sale be concluded, it will stand as the second largest sale of U.S. arms to one particular nation, and the first transfer of lethal unmanned aerial systems to any Arab ally. The UAE would be the first Arab country to possess the Lockheed Martin 5th generation stealth jet, the most advanced on the market currently.

There is debate within Israel regarding possible UAE acquisition of the F-35 systems. Prime Minister Netanyahu did the whole deal without including the defense minister and the foreign minister, both political rivals of Netanyahu in the Israeli system. As can be expected, the Israeli defense minister does have a problem regarding the F-35 systems. However, in general, the Accords are extremely popular in Israel.

Due to Bahrain’s relative dependence on Saudi Arabia and the kingdom’s close ties, it is very likely that it sought out Saudi Arabia’s approval before confirming its participation in the Accords. The fact that Saudi Arabia gave permission to Bahrain could be seen as indicative, to a certain extent, of their stance on Arab-Israeli relations. However, the Saudi state has many internal pressures preventing it, at least for the time being, from establishing relations.

For over 250 years, the ruling Saudi family has had a particular relationship with the clerical establishment of the Kingdom. Many, if not the majority of the clerics would be critical of what they would consider an abandonment of Palestine. Although Mohammed bin Salman seems more open to ties with Israel, his influential father, Salman bin Abdulaziz sides with the clerics surrounding the matter.

Differing from the United Arab Emirates, for example, Saudi Arabia gathers a notable amount of its legitimacy through its protection of Muslims and promotion of Islam across the world. Since before the establishment of the state of Israel, the Palestinian cause has played a crucial role in Saudi Arabia’s regional activities. While it has not prevented Saudi Arabia from engaging in undisclosed relations with Israel, its stance towards Palestine inhibits a broader engagement without a peace deal for Palestine. This issue connected to a critical strain across the region: that between the rulers and the ruled. One manifestation of this discrepancy between classes is that there seems to be a perception among the people of the region that Israel, as opposed to Iran, is the greater threat to regional security. Saudi Arabia has a much larger population than the UAE or Bahrain and with the extensive popular support of the Palestinian cause, the establishment of relations with Israel could elicit considerable unrest.

While Saudi Arabia has engaged in clandestine ties with Israel and been increasingly obliging towards the state (for instance, opening its air space for Israeli direct flights to the UAE and beyond), it seems unlikely that Saudi Arabia will establish open ties with Israel, at least for the near future.

The ongoing coronavirus pandemic has only heightened prevailing social, political and economic tensions all throughout the Middle East. Taking this into account, in fear of provoking unrest, it can be expected that many rulers will be hesitant, or at least cautious, about initiating ties with the state of Israel.

That being said, in today’s hard-pressed Middle East, Arab states, while still backing the Palestinian cause, are more and more disposed to work towards various relations with Israel. Saudi Arabia is arguably the most economically and politically influential Arab state in the region. Therefore, if Saudi Arabia were to open relations with Israel, it could invoke the establishment of ties with Israel for other Arab states, possibly invalidating the longstanding idea that such relations could come about solely though the resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Regarding Iran, it cannot but understand the significance and gravity of the Accords and recent regional developments. Just several nautical miles across the Gulf to Iran, Israel has new allies. The economic and strategic advantage that the Accords promote between the countries is undeniable. If Iran felt isolated before, this new development will only emphasize it even more.

In the words of Mike Pompeo, the current U.S. Secretary of State, alongside Bahrain’s foreign minister, Abdullatif Al-Zayani, and Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, the accords “tell malign actors like the Islamic Republic of Iran that their influence in the region is waning and that they are ever more isolated and shall forever be until they change their direction.”

Apart from Iran, in the Middle East Turkey and Qatar have been openly vocal in their opposition to Israel and the recent Accords. Qatar maintains relations with two of Israel’s most critical threats, both Iran and Hamas, the Palestinian militant group. Qatar is a staunch advocate of a two-state solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict. One of Qatar’s most steady allies in the region is Turkey. Israel, as well as the UAE, have significant issues with Ankara. Turkey’s expansion and building of military bases in Libya, Sudan and Somalia demonstrate the regional threat that it poses for Israel and the UAE. For Israel in particular, besides Turkey’s open support of Hamas, there have been clashes concerning Ankara’s interference with Mediterranean maritime economic sovereignty.

With increasing intensity, the President of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has made clear Turkey’s revisionist actions. They harshly criticized UAE’s normalization with Israel and even said that they would consider revising Ankara’s relations with Abu Dhabi. This, however, is somewhat incongruous as Turkey has maintained formal diplomatic relations with Israel since right after its birth in 1949. Turkey’s support of the Muslim Brotherhood throughout the region, including in Qatar, is also a source of contention between Erdogan and the UAE and Israel, as well as Saudi Arabia. Turkey is Qatar’s largest beneficiary politically, as well as militarily.

In the context of the Abraham Accords, the Palestinians would be the losers undoubtedly. While they had a weak negotiating hand to begin with, with the decreasing Arab solidarity they depend on, they now stand even feebler. The increasing number of Arab countries normalizing relations with Israel has been vehemently condemned by the Palestinians, seeing it as a betrayal of their cause. They feel thoroughly abandoned. It leaves the Palestinians with very limited options making them severely more debilitated. It is uncertain, however, whether this weaker position will steer Palestinians towards peacemaking with Israel or the contrary.

While the regional governments seem more willing to negotiate with Israel, it would be a severe mistake to disregard the fervor with which countless people still view the Palestinian conflict. For many in the Middle East, it is not so much a political stance as a moral obligation. We shall see how this plays out concerning the disparity between the ruling class and the populace of Arab or Muslim majority nations. Iran will likely continue to advance its reputation throughout the region as the only state to openly challenge and oppose Israel. It should amass some amount of popular support, increasing yet even more the rift between the populace and the ruling class in the Middle East.

Future prospects

The agreement recently reached between President Trump’s Administration and the kingdom of Morocco by which the U.S. governments recognizes Moroccan sovereignty over the disputed territory of Western Sahara in exchange for the establishment of official diplomatic relations between the kingdom and the state of Israel is but another step in the process Trump would have no doubt continued had he been elected for a second term. Despite this unexpected move, and although the Trump Administration has indicated that other countries are considering establishing relations with Israel soon, further developments seem unlikely before the new U.S. Administration is projected to take office this January of 2021. President-elect Joe Biden will take office on the 20th of January and is expected to instigate his policy and approach towards Iran. This could set the tone for future normalization agreements throughout the region, depending on how Iran is approached by the incoming administration.

In the United States, the signatories of the Abraham Accords have, in a time of intensely polarized politics, enhanced their relations with both Republicans as well as Democrats though the deal. In the future we can expect some countries to join the UAE, Bahrain and Sudan in normalization efforts. However, many will stay back. Saudi Arabia remains central in the region regarding future normalization with Israel. As is the case across the region, while the Arab leaders are increasingly open to ties with Israel, there are internal concerns, between the clerical establishment and the Palestinian cause among the populace – not to mention rising tensions due to the ongoing pandemic.

However, in all, the Accords break the strongly rooted idea that it would take extensive efforts in order for Arab states to associate with Israel, let alone establish full public normalization. It also refutes the traditional Arab-state consensus that there can be no peace with Israel until the Palestinian issue is en route to resolution, if not fully resolved.

Behind the tension between Qatar and its neighbors is the Qatari ambitious foreign policy and its refusal to obey

Recent diplomatic contacts between Qatar and Saudi Arabia have suggested the possibility of a breakthrough in the bitter dispute held by Qatar and its Arab neighbors in the Gulf since 2017. An agreement could be within reach in order to suspend the blockade imposed on Qatar by Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain (and Egypt), and clarify the relations the Qataris have with Iran. The resolution would help Qatar hosting the 2022 FIFA World Cup free of tensions. This article gives a brief context to understand why things are the way they are.

▲ Ahmad Bin Ali Stadium, one of the premises for the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar

ARTICLE / Isabelle León

The diplomatic crisis in Qatar is mainly a political conflict that has shown how far a country can go to retain leadership in the regional balance of power, as well as how a country can find alternatives to grow regardless of the blockade of neighbors and former trading partners. In 2017, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain broke diplomatic ties with Qatar and imposed a blockade on land, sea, and air.

When we refer to the Gulf, we are talking about six Arab states: Saudi Arabia, Oman, UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait. As neighbors, these countries founded the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in 1981 to strengthen their relation economically and politically since all have many similarities in terms of geographical features and resources like oil and gas, culture, and religion. In this alliance, Saudi Arabia always saw itself as the leader since it is the largest and most oil-rich Gulf country, and possesses Mecca and Medina, Islam’s holy sites. In this sense, dominance became almost unchallenged until 1995, when Qatar started pursuing a more independent foreign policy.

Tensions grew among neighbors as Iran and Qatar gradually started deepening their trading relations. Moreover, Qatar started supporting Islamist political groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood, considered by the UAE and Saudi Arabia as terrorist organizations. Indeed, Qatar acknowledges the support and assistance provided to these groups but denies helping terrorist cells linked to Al-Qaeda or other terrorist organizations such as the Islamic State or Hamas. Additionally, with the launch of the tv network Al Jazeera, Qatar gave these groups a means to broadcast their voices. Gradually the environment became tense as Saudi Arabia, leader of Sunni Islam, saw the Shia political groups as a threat to its leadership in the region.

Consequently, the Gulf countries, except for Oman and Kuwait, decided to implement a blockade on Qatar. As political conditioning, the countries imposed specific demands that Qatar had to meet to re-establish diplomatic relations. Among them there were the detachment of the diplomatic ties with Iran, the end of support for Islamist political groups, and the cessation of Al Jazeera's operations. Qatar refused to give in and affirmed that the demands were, in some way or another, a violation of the country's sovereignty.

A country that proves resilient

The resounding blockade merited the suspension of economic activities between Qatar and these countries. Most shocking was, however, the expulsion of the Qatari citizens who resided in the other GCC states. A year later, Qatar filed a complaint with the International Court of Justice on grounds of discrimination. The court ordered that the families that had been separated due to the expulsion of their relatives should be reunited; similarly, Qatari students who were studying in these countries should be permitted to continue their studies without any inconvenience. The UAE issued an injunction accusing Qatar of halting the website where citizens could apply for UAE visas as Qatar responded that it was a matter of national security. Between accusations and statements, tensions continued to rise and no real improvement was achieved.

At the beginning of the restrictions, Qatar was economically affected because 40% of the food supply came to the country through Saudi Arabia. The reduction in the oil prices was another factor that participated on the economic disadvantage that situation posed. Indeed, the market value of Qatar decreased by 10% in the first four weeks of the crisis. However, the country began to implement measures and shored up its banks, intensified trade with Turkey and Iran, and increased its domestic production. Furthermore, the costs of the materials necessary to build the new stadiums and infrastructure for the 2022 FIFA World Cup increased; however, Qatar started shipping materials through Oman to avoid restrictions of UAE and successfully coped with the status quo.

This notwithstanding, in 2019, the situation caused almost the rupture of the GCC, an alliance that ultimately has helped the Gulf countries strengthen economic ties with European Countries and China. The gradual collapse of this organization has caused even more division between the blocking countries and Qatar, a country that hosts the largest military US base in the Middle East, as well as one of Turkey, which gives it an upper hand in the region and many potential strategic alliances.

The new normal or the beginning of the end?