![Members of the Blue Helmets in their deployment in Mali [MINUSMA] Members of the Blue Helmets in their deployment in Mali [MINUSMA]](/documents/10174/16849987/minusma-blog.jpg)

▲ Members of the Blue Helmets in their deployment in Mali [MINUSMA]

ESSAY / Ignacio Yárnoz

INTRODUCTION

It has been 72 years since the first United Nations peacekeeping operation was deployed in Israel/Palestine to supervise the ceasefire agreement between Israel and his Arab neighbours. Since then, more than 70 peacekeeping operations have been deployed by the UN all over the world, though with special attention to the Middle East and Africa. Over these more than 70 years, hundreds of thousands of military personnel from more than 120 countries have participated in UN peacekeeping operations. Nowadays, there are 13 UN peacekeeping operations deployed in the world, seven of which are located in African countries supported by a total of 83,436 thousand troops (around 80 percent of all UN peacekeepers deployed around the world) and thousands of civilians. The largest missions in terms of number of troops and ambitious objectives are those in the Democratic Republic of Congo (20,039 troops), South Sudan (19,360 troops), and Mali (15,162 troops)[1].

Peacekeepers in Africa, as in other regions, are given broad and ambitious mandates by the Security Council which include civilian protection, counterterrorism, and counterinsurgency operations or protection of humanitarian relief aid. However, these objectives must go hand by hand with the core UN peacekeepers principles, which are consent by the belligerent parties, impartiality (not neutrality) and the only use of force in case of self-defence[2].

Although peace operations can be important for maintaining stability and safeguarding democratic transitions, multilateral institutions such as UN face challenges related to country contributions, training, a very hostile environment and relations with host governments. It is often stated that these missions have failed largely because they were deployed in a context of ongoing wars where the belligerents themselves did not want to stop fighting or preying on civilians and yet have to manage to protect many civilians and reduce some of the worst consequences of civil war.

In addition, UN peacekeepers are believed to be deployed in the most recent missions to war zones where not all the main parties have consented. There is also mounting international pressure for peacekeepers to play a more robust role in protecting civilians. Despite the principle of impartiality, UN peacekeepers have been tasked with offensive operations against designated enemy combatants. Contemporary mandates have often blurred the lines separating peacekeeping, stabilization, counterinsurgency, counterterrorism, atrocity prevention, and state-building.

Such features have often been referred to the case of the peacekeeping operation in Mali (MINUSMA) as I will try to sum up in this essay. This mission, ongoing since 2013 is on his seventh year and tensions between the parties have still not ceased due to several reasons I will further explain I this essay. Through a summarized history of the ongoing conflict, an explanation of the current military/police deployment, the engagement of third parties and an assessment on the risks and opportunities of this mission as well as an analysis of its successes and failures I will try to give a complete analysis on what MINUSMA is and its challenges.

Brief history of the conflict in Mali

During the last 8 years, Mali has been immersed in a profound crisis of Governance, socio-economic instability, terrorism and human rights violations. The crisis mentioned stems from several factors I will try to develop in this first part of the analysis. The crisis derives from long-standing structural conditions that Mali has experienced, such as ineffective Governments due to weak State institutions; fragile social cohesion between the different ethnic and religious groups; deep-rooted independent feelings among communities in the north due to marginalization by the central Government and a weak civil society among others. These conditions were far exacerbated by more recent instability, a spread corruption, nepotism and abuse of power by the Government, instability from neighbouring countries and a decreased effective capacity of the national army.

It all began in mid-January 2012 when a Tuareg movement called Mouvement National pour la Libération de l’Azawad (MNLA) and some Islamic armed groups such as Ansar Dine, Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Mouvement pour l’Unicité et le Jihad en Afrique de l’Ouest (MUJAO) initiated a series of attacks against Government forces in the north of the country[3]. Their primary goals for this rebel groups though different could be summarized into declaring the Northern regions of Timbuktu, Kidal and Gao (the three together called Azawad) independent from the Central Government of Mali in Bamako and re-establishing the Islamic Law in these regions. The Tuareg led rebellion was reinforced by the presence of well-equipped and experienced combatants returning from Libya´s revolution of 2011 in the wake of the fall of Gadhafi’s regime[4].

By March 2012, the Malian Institutions had been overwhelmingly defeated by the rebel groups and the MNLA seemed to almost have de facto taken control of the North of Mali. As a consequence of the ineffectiveness to handle the crisis, on 22 March a series of disaffected soldiers from the units defeated by the armed groups in the north resulted in a military coup d’état led by mid-rank Capt Aamadou Sanogo. Having overthrown President Amadou Toumane Toure, the military junta took power, suspended the Constitution and dissolved the Government institutions[5]. The coup accelerated the collapse of the State in the north, allowing MNLA to easily overrun Government forces in the regions of Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu and proclaim an independent State of Azawad on 6 April. The Military junta promised that the Malian army would defeat the rebels, but the ill-equipped and divided army was no match for the firepower of the rebels.

Immediately after the coup, the International Community condemned this act and lifted sanctions against Mali if the situation wasn't restored. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) appointed the President of Burkina Faso, Blaise Compaoré, as the mediator on the crisis and compromised the ECOWAS would help Malian Government to restore order in the Northern region if democracy was brought back[6]. On 6 April, the military junta and ECOWAS signed a framework agreement that led to the resignation of Capt Aamadou Sanogo and the appointment of the Speaker of the National Assembly, Dioncounda Traoré, as interim President of Mali on 12 April. On 17 April, Cheick Modibo Diarra was appointed interim Prime Minister and three days later, he announced the formation of a Government of national unity.

However, something happened during the rest of the year 2012 after the Malian government forces had been defeated. Those who were allies one day, became enemies of each other and former co-belligerents Ansar Dine, MOJWA, and the MNLA soon found themselves in a conflict.

Clashes began to escalate especially between the MNLA and the Islamists after a failure to reach a power-sharing treaty between the parties. As a consequence, the MNLA forces soon started to be driven out from the cities of Kidal, Timbuktu and Gao. The MNLA forces lacked as many resources as the Islamist militias and had experienced a loss of recruits who preferred the join the better paid Islamist militias. However, the MNLA stated that it continued to maintain forces and control some rural areas in the region. As of October 2012, the MNLA retained control of the city of Ménaka, with hundreds of people taking refuge in the city from the rule of the Islamists, and the city of Tinzawatene near the Algerian border. Whereas the MLNA only sought the Independence of Azawad, the Islamist militias goal was to impose the sharia law in their controlled cities, which drove opposition from the population.

Foreign intervention

Following the events of 2012, the Malian interim authorities requested United Nations assistance to build the capacities of the Malian transitional authorities regarding several key areas to the stabilization of Mali. Those areas were the reestablishment of democratic elections, political negotiations with the opposing northern militias, a security sector reform, increased governance on the entire country and humanitarian assistance.

The call for assistance came in the form of a UN deployment in mid-January 2013 authorized by Security Council resolution 2085 of 20 December 2012. This resolution gave the UN a mandate with two clear objectives: provide support to (i) the on-going political process and (ii) the security process, including support to the planning, deployment and operations of the African-led International Support Mission in Mali (AFISMA)[7].

The newly designated mission was planned to be an African led mission (Africa Union and ECOWAS) and funded through the UN trust fund and the European Union Africa Peace Facility. The mission was mandated several objectives: (i) contribute to the rebuilding of the capacity of the Malian Defence and Security Forces; (ii) support the Malian authorities in recovering the areas in the north; (iii) support the Malian authorities in maintaining security and consolidate State authority; (iv) provide protection to civilians and (iv) support the Malian authorities to create a secure environment for the civilian-led delivery of humanitarian assistance and the voluntary return of internally displaced persons and refugees.

However, the security situation in Mali further deteriorated in early January 2013, when the three main Islamist militias Ansar Dine, the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa and Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, advanced southwards. After clashing with the Government forces north of the town of Konna, some 680 kilometres from Bamako, the Malian Army was forced to withdraw. This advance by the Islamist militias raised the alarms in the International arena as they were successfully taking control of key areas and strategic spots in the country and could soon advance to the capital if nothing was done.

The capture of Konna by extremist groups made the Malian transitional authorities to consider requesting once again the assistance of foreign countries, in especial to its ancient colonizer France, who accepted launching a military operation to support the Malian Army. It is also true that France was already keen on intervening as soon as possible due the importance of Sévaré military airport, located 60 km south of Konna, for further operations in the Sahel area.

Operation Serval, as coined by France, was initiated on 11 January with a deployment of a total of 3,000 troops[8] and air support from Mirage 2000 and Rafale squadrons. In addition, the deployment of AFISMA to support the French deployment was fostered. As a result, the French and African military operations alongside the Malian army successfully improved the security situation in northern areas of Mali. By the end of January, State control had been restored in most major northern towns, such as Diabaly, Douentza, Gao, Konna and Timbuktu. Most terrorist and associated forces withdrew northwards into the Adrar des Ifoghas mountains and much of their leaders such as Abdelhamid Abou Zeid were reported eliminated.

Despite taking control back to the government authorities and restoring the territorial integrity of the country, serious security challenges remained. Although the main cities had been taken back, terrorist attacks remained frequent, weapons proliferated in the rural and urban areas, drug smuggling was increasing and other criminal activities were also maintained active, which undermine governance and development in Mali. Therefore, the fight just transitioned from a territorial and conventional war to a guerrilla style warfare much more difficult to neutralise.

United Nations deployment

Following the gradual withdrawal of the French troops from Mali (Operation Serval evolved to Operation Barkhane in the Sahel region), AFISMA took responsibility to secure the stabilization and the implementation of a transitional roadmap which demanded more resources and engagement from more countries. As a consequence, AFISMA mission officially transitioned to be MINUSMA (United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali) by Security Council Resolution 2100 of April 25, 2013[9].

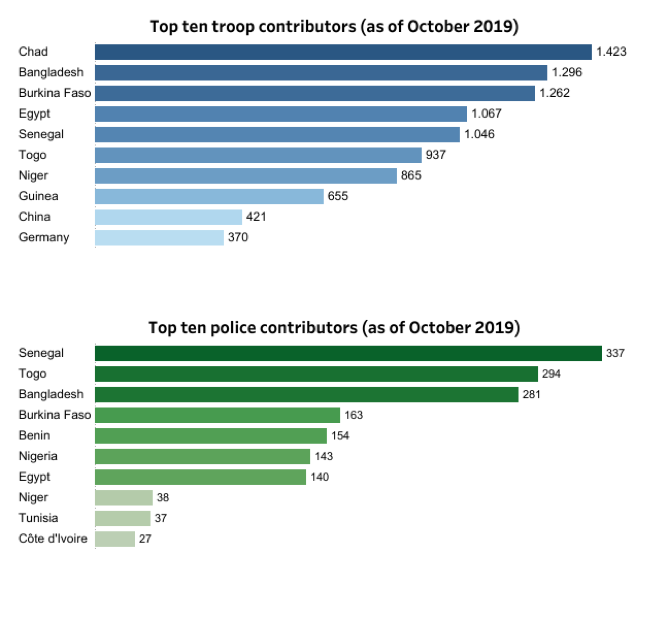

Seven years after, MINUSMA mission accounts with a deployment of 11,953 military personnel, 1,741 police personnel and 1,180 civilians (661 national - 585 international, including 155 United Nations Volunteers)[10] deployed in 4 different sectors: Sector North (Kidal, Tessalit, Aguelhoc) Sector South (Bamako) Sector East (Gao, Menaka, Ansongo) Sector West (Tombouctou, Ber, Diabaly, Douentza, Goundam, Mopti-Sevare). The $1 Billion budget mission (financed by UN regular budget on Peacekeeping operations) accounts with personnel from more than 50 different countries being Chad, Bangladesh or Burkina Faso the biggest contributors in terms of number of troops (Figure 1).

The command and control of the ground forces is headed by both commanders Lieutenant General Dennis Gyllensporre (military deployment) and MINUSMA Police Commissioner Issoufou Yacouba (police deployment). Regarding the political leadership of the mission, the Special Representative of the Secretary-general (SRSG) and Head of MINUSMA is Mr. Mahamat Saleh Annadif, an experienced diplomat on peace processes in Africa and former minister of Foreign Affairs of Chad.

Other international actors engaged

MINUSMA however is not the only international actor engaged in the security and political process of Mali. Institutions as the European Union are also in the ground helping specifically on the training of the Malian Army and helping develop their military capabilities.

The European Union Training Mission in Mali[11] (EUTM Mali) is composed of almost 600 soldiers from 25 European countries including 21 EU members and 4 non-member states (Albania, Georgia, Montenegro and Serbia). Since the beginning of the mission initially designed to end 15 months after the start in 2013 (First Mandate), there have been several extensions of the periods to end the mission by Council Decision (Second Mandate 2014-2016, Third Mandate 2016-2018) until today where we are on the Fourth Mandate (Extended until 2020 by Council Decision 2018/716/CFSP in May 2018). The strategic objectives of the 4th Mandate are:

-

1st to contribute to the improvement of the capabilities of the Malian Armed Forces under the control of the political authorities.

-

2nd to support G5 Sahel Joint Force, through the consolidation and improvement of the operational capabilities of its Joint Force, strengthening regional cooperation to address common security threats, especially terrorism and illegal trafficking, especially of human beings.

Regarding this last actor mentioned, the G5 Sahel Joint force (Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad) is an intergovernmental cooperation framework created on 16 February 2014 and seeks to fight insecurity and support development in the Sahel Region with the train and support of the European Union and external donors.

Its first operation, launched on July 2017, consisted in a Cross-Border Joint Force settled in Bamako to fight terrorism, cross-border organized crime and human trafficking in the G5 Sahel zone in the Sahel region. The United Nations Security Council welcomed the creation of this Joint Force in Resolution 2359 of 21 June 2017, which was sponsored by France[12]. At full operational capability, the Joint Force will have 5,000 soldiers (seven battalions spread across three zones: West, Centre and East). It is active in a 50 km strip on either side of the countries’ shared borders. Later on, a counter-terrorism brigade is to be deployed to northern Mali.

Finally, as I explained before, France gradually withdrew from Mali and transformed Operation Serval to Operation Barkhane[13], a force, with approximately 4,500 soldiers, spread out between Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad to counter the terrorist threat on these territories. With a budget of nearly €600m per year, it is France’s largest overseas operation and engages activities such as combat patrols, intelligence gathering and filling the Governance gap of the absent Government institutions.

Troop and Police contributors to MINUSMA [Source: UN]

Retrieved from MINUSMA Fact Sheet[25]

Assessment on the situation of MINUSMA

Since its establishment, MINUSMA has achieved some of its objectives in its early stages. From 2013 to 2016, the situation in Northern Mali improved, the numbers of civilians killed in the conflict decreased and large numbers of displaced persons could return home. In addition, MINUSMA supported the celebration of new elections in 2013 and assisted the peace process mainly between the Tuareg rebels and the Government. The peace process culminated in the 15 May 2015 with the Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in Mali, commonly referred as the Algiers Agreement[14][15].

The Algiers Agreement was an accord concluded between the Malian Government and two coalitions of armed groups that were fighting the government and against each other, being (i) the Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA) and (ii) the Platform of armed groups (the Platform). Although imperfect, the peace agreement gave the basis to a continued dialogue and steps were made by the Government regarding the devolution of competences to regional institutions, laws of reconciliation and reintegration of combatants and resources devoted to infrastructure projects in the northern regions[16].

However, since 2016 the situation has deteriorated in several aspects. Violence has increased as jihadist groups have been attacking MINUSMA forces, the Forces Armées Maliennes (FAMA), and the Algiers Agreement signatories (CMA and the platform). As a consequence, MINUSMA has sustained an extraordinary number of fatalities compared to other recent UN peace operations.

Since the beginning of the Mission in 2013, 206 MINUSMA peacekeepers have died during service in Mali[17]. In the last report of Secretary General, it is noted that during the months of October, November and December 2019, there have been 68 attacks against MINUSMA troops in the regions of Mopti (46), Kidal (9), Ménaka (5), Timbuktu (4) and Gao (4) resulting in the deaths of two peacekeepers and eight contractors and in injury to five peacekeepers, one civilian and two contractors[18].

During this same period, the Malian Armed Forces have also experienced a loss of 193 soldiers and 126 injured. The deadliest attacks occurred in Boulikessi and Mondoro (Mopti Region) on 30 September; in Indelimane (Ménaka Region) on 1 November; and in Tabankort (Ménaka Region) on 18 November. MINUSMA provided support for medical evacuations for the national defence and security forces, as well as fuel and equipment to reinforce some camps.

In addition, during this last 3 months, there have been 269 incidents, in which 200 civilians were killed, 96 civilians were injured and 90 civilians were abducted. More than 85 per cent of deadly attacks against civilians took place in Mopti Region. Between 14 and 16 November, a series of attacks against Fulani villages in Ouankoro commune resulted in the killing of at least 37 persons.

As we can see from the data, Mopti region has further deteriorated regarding civilian protection and increased terrorist activity. What is more surprising is that this region in not located in the north but rather in the centre of the country. Mopti and Ségou regions in central Mali are where violence is increasingly spreading. Two closely intertwined drivers of violence can be distinguished: interethnic violence and jihadist violence against the state and its supporters.

The attacks directed primarily towards the Malian security forces and MINUSMA by jihadists have been committed by the jihadist group Katiba Macina, which is part of the GSIM (Le Groupe de Soutien à l'Islam et aux Musulmans), a merger organisation resulting from the fusion of Ansar Dine, forces from Al-Qaïda au Maghreb Islamique (AQMI), Katiba Macina and Katiba Al-Mourabitoune. This organisation formed in 2017 has triggered the retreat of an already relatively absent state in the central areas. The Katiba exerts violence against representatives of the state (administrators, teachers, village chiefs, etc.) in the Mopti region, provoking that only 30 to 40 per cent of the territorial administration personnel remains present. Additionally, only 1,300 security forces are stationed across the vast region (spanning 79,000 km²).

Between the Jihadist activities and the retaliation activities by government forces, there has been a collateral consequence as self-defence militias have proliferated. However, these militias have not only exerted self-defence but also criminal activities and competition over scarce local resources. To this problem we have to add the ethnic component where violence exerted by militias is associated with ethnic differences (mainly the Dogon and Fulani). Jihadists have instrumentalised this rivalry to gain sympathizers and recruits and turned the radicalisation problem and the interethnic rivalry a vicious trap. The ethnicisation of the conflict reinforces the stigmatisation of the Fulani as “terrorists”. Meanwhile, the state has tolerated and even cooperated with the Dogon militia to cope with the terrorist threat. However, this groups are supposedly responsible for human rights violations, which again fosters radicalisation among the Fulani population feeling they are left alone in this conflict. As a matter of fact, the Dogon Militia is alleged to be responsible of the 23 March assassination of 160 Fulani in the village of Ogossagou (Mopti Region)[19].

Northern Mali has not remained calmed meanwhile, the Ménaka region has also experienced a violence raise. Recent counterterrorism efforts led by ethnically based militias resulted in a counterproductive effects leading to human rights violations and atrocities between Tuareg Daoussahaq and Fulani communities. Due to again the absence Malian security forces or MINUSMA blue helmets, civilians have had no choice but to rely on their own self-protection or on armed groups present in the area, escalating the vicious problem of violence as in the Mopti region.

Strategic dilemmas of MINUSMA

Given this situation, several dilemmas arise in the current situation in which the mission is. The original Mandate of MINUSMA for 5 years has already expired and now the mission is in a phase of renewal year by year, which makes it a suitable time to rethink the overall path where this mission should continue.

The fist dilemma arises given the split of the violent spots between the north and the centre of the country. MINUSMA was originally set up to stabilize the conflict in the north, but MINUSMA’s 2019 Resolution 2480[20] has derived some attention and resources to the central regions and particularly on Protection of Civilians while maintaining its presence in the north too. However, the only problem is that this division on two has not come hand in hand with an increase in resources devoted to the mission, which means that attention paid to the central regions may be in spite of gains made in the north, making the MINUSMA mandate even more unrealistic.

This dilemma raises the problem of financing of the mission. As the years passes, financers of the mission (those that contribute to the General Budget on Peace Keeping Operations of UN) such as the US are getting impatient of not seeing results to a mission where $1 Billion is devoted out of the around $8 Billion of the General Budget. The problem is that for MINUSMA to accomplish its mission in Northern Mali, it has to make an enormous military and logistical effort. The ongoing violent situation calls for security precautions that tie up scarce resources which are no longer available for carrying out the mandate. To illustrate the problem, we can look at the expenditures of the mission and discover that around 80 per cent of its military resources are devoted to securing its own infrastructure and the convoys on which the mission depends to supply its bases[21].

A final dilemma is related to the development of the terrorist threat. As we have analysed in this article, today´s conflict in Mali is about terrorism and therefore requires counterterrorist strategies. However, there are people that state that MINUSMA should focus on the politics part of the conflict stressing its efforts on the peace agreement. Current counterterrorism efforts conducted by the Malian Army are highly problematic as they have fuelled local opposition due to its poor human rights commitment. It has been reported the use of ethnic proxy militias (Such as the Dogon militias in Mopti region) who are responsible for committing atrocities against the civilian population. This makes the Central Government to be an awkward and not very trustworthy partner for MINUSMA. At the same time, returning to political tasks alone may further destabilize the country and possibly the whole Sahel-West African region.

Conclusion

There is no doubt MINUSMA operates hostile environment where around half of all blue helmets killed worldwide through malign acts since 2013 have lost their lives. However, MINUSMA has been heavily criticised by public opinion in Mali and accused of passivity regarding protection of civilians whereas critics say, blue helmets have placed their own security above the rest. The has contributed to this public perception by using the mission’s problems as a scapegoat for its own failures. However, the mission (with its successes and failures) brings more advantages than inconveniences to the overall process of stabilization of Mali[22].

As many diplomats in Bamako and other public officials stress, the mission and its chief, Mahamat Saleh Annadif, play an important role as mediators both in Bamako politics and with respect to the peace agreement. We cannot discredit the mission of its contribution to Mali´s stabilisation. As a matter of fact, it is legitimate to claim that the situation would be much worse without MINUSMA. Yet, the mission has not stopped the spread of violence but rather slowed down the deterioration process of the situation.

While much presence is still needed in northern Mali, we should not forget that the core of the problem to Mali´s instability is partly on the political arena and therefore needs mediation. Therefore, importance of continuing political and military support to the peace process should not be underestimated.

At the same time, we have seen the situation over protection of civilians has worsened in the central regions, which requires additional resources. Enhancing MINUSMA’s outreach and representation might prevent the central regions from collapsing, though solutions need to be found to ensure stability in the long term through mediation too. Further expanding the mission in the central regions without affecting the deployment in the north and, therefore, not risking the stability of those regions, would require that MINUSMA have additional resources. This would clearly be the best option for Mali.

Resources could for instance be devoted to improve the lack of mobility in the form of helicopters and armoured carriers to make it possible for the mission to expand its scope beyond the vicinity of its bases. Staying in the bases makes MINUSMA more of a target than a security provider and only provides security to its nearby zones where the base is physically present. In addition, the most dangerous missions are carried out by African peacekeepers despite lacking adequate means whereas European countries´ peacekeepers are mostly based in MINUSMA’s headquarters in Bamako, Gao, or Timbuktu. While European peacekeepers possess more sophisticated equipment such as surveillance drones and air support, African troops do not benefit from those and have to face the most challenging geographical and security environments escorting logistical convoys[23].

Additionally, by accelerating the re-integration of former rebels to the Malian security forces, encouraging Malian police training, and demonstrating increased presence through joint patrols in most instable areas to protect civilians are key to minimize the threat of further violence. Increased state visibility as we have analysed in this essay has driven to insecurity situations. Consequently, if it can be as much of the problem, it can also be the solution to re-establish some of its legitimacy alongside with the signatories of the Peace Accord to show good faith and engagement in the peace process[24].

In the end, any contribution MINUSMA can make will depend on the willingness of Malians to strive for an effective and inclusive government on the one hand and the commitment of the International community on the other. Supporting such a long-term process cannot be done on the cheap. Therefore, countries cannot continue to request to do more with the same or even less resources.

NOTES

[1] United Nations Peacekeeping. (n.d.). Where we operate. [online] Available at [Accessed 21 Dec. 2019].

[2] Renwick, D. (2015). Peace Operations in Africa. [online] Council on Foreign Relations. Available at [Accessed 21 Dec. 2019].

[3] Welsh, M. Y. (2013, January 17). Making sense of Mali's armed groups. Al Jazeera. Available at [Accessed 22 Dec. 2019].

[4] Timeline on Mali. (n.d.). New York Times. Available at [Accessed 22 Dec. 2019].

[5] Oberlé, T. (2012, March 22). Mali : le président renversé par un coup d'État militaire. Le Figaró. Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

[6] MINUSMA. (n.d.). History. [online] Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

[7] Unscr.com. (2012). Security Council Resolution 2085 - UNSCR. [online] Available at [Accessed 23 Dec. 2019].

[8] BBC News. (2013). France confirms Mali intervention. [online] Available at [Accessed 24 Dec. 2019].

[9] Security Council Resolution 2100 - UNSCR. (2013). Available at [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

[11] EUTM Mali. (n.d.). DÉPLOIEMENT - EUTM Mali. [online] Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

[12] France Diplomatie: Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. (n.d.). G5 Sahel Joint Force and the Sahel Alliance. [online] Available at [Accessed 27 Dec. 2019].

[13] Ecfr.eu. (2019). Operation Barkhane - Mapping armed groups in Mali and the Sahel. [online] Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

[14] Un.org. (2015). AGREEMENT FOR PEACE AND RECONCILIATION IN MALI RESULTING FROM THE ALGIERS PROCESS. [online] Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

[15] Jezequel, J. (2015). Mali's peace deal represents a welcome development, but will it work this time? | Jean-Hervé Jezequel. Available at [Accessed 8 Jan. 2020].

[16] Nyirabikali, D. (2015). Mali Peace Accord: Actors, issues and their representation | SIPRI. Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

[18] Digitallibrary.un.org. (n.d.). "UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali" OR MINUSMA - United Nations Digital Library System. [online] Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

[19] McKenzie, D. (2019). Ogossagou massacre is latest sign that violence in Mali is out of control. Available at [Accessed 4 Jan. 2019].

[20] Unscr.com. (2019). Security Council Resolution 2480 - UNSCR. [online] Available at [Accessed 10 Jan. 2019].

[21] United Nations Digital Library System. (2019). Budget for the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali for the period from 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020. [online] Available at [Accessed 4 Jan. 2020].

[22] Van der Lijn, J. (2019). The UN Peace Operation in Mali: A Troubled Yet Needed Mission - Mali. [online] ReliefWeb. Available at [Accessed 30 Dec. 2019].

[23] Lyammouri, R. (2018). After Five Years, Challenges Facing MINUSMA Persist. Available at [Accessed 6 Jan. 2020].

[24] Tull, D. (2019). UN Peacekeeping in Mali. [online] Swp-berlin.org. Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

[25] MINUSMA. MINUSMA Fact Sheet. Available at [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

BIBLIOGRAPHY

United Nations Peacekeeping. (n.d.). Where we operate. [online] Available at [Accessed 21 Dec. 2019].

Renwick, D. (2015). Peace Operations in Africa. [online] Council on Foreign Relations. Available at [Accessed 21 Dec. 2019].

Timeline on Mali. (n.d.). New York Times. Available at [Accessed 22 Dec. 2019].

Welsh, M. Y. (2013, January 17). Making sense of Mali's armed groups. Al Jazeera. Available at [Accessed 22 Dec. 2019].

MINUSMA. (n.d.). History. [online] Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

Oberlé, T. (2012, March 22). Mali : le président renversé par un coup d'État militaire. Le Figaró. Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

Unscr.com. (2012). Security Council Resolution 2085 - UNSCR. [online] Available at [Accessed 23 Dec. 2019].

BBC News. (2013). France confirms Mali intervention. [online] Available at [Accessed 24 Dec. 2019].

MINUSMA. (n.d.). Personnel. [online] Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

EUTM Mali. (n.d.). DÉPLOIEMENT - EUTM Mali. [online] Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

France Diplomatie: Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. (n.d.). G5 Sahel Joint Force and the Sahel Alliance. [online] Available at [Accessed 27 Dec. 2019].

Ecfr.eu. (2019). Operation Barkhane - Mapping armed groups in Mali and the Sahel. [online] Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

Un.org. (2015). AGREEMENT FOR PEACE AND RECONCILIATION IN MALI RESULTING FROM THE ALGIERS PROCESS. [online] Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

Digitallibrary.un.org. (n.d.). "UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali" OR MINUSMA - United Nations Digital Library System. [online] Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

United Nations Digital Library System. (2019). Budget for the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali for the period from 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020. [online] Available at [Accessed 4 Jan. 2020].

Van der Lijn, J. (2019). The UN Peace Operation in Mali: A Troubled Yet Needed Mission - Mali. [online] ReliefWeb. Available at [Accessed 30 Dec. 2019].

Tull, D. (2019). UN Peacekeeping in Mali. [online] Swp-berlin.org. Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

McKenzie, D. (2019). Ogossagou massacre is latest sign that violence in Mali is out of control. Available at [Accessed 4 Jan. 2019].

Unscr.com. (2019). Security Council Resolution 2480 - UNSCR. [online] Available at [Accessed 10 Jan. 2019].

Security Council Resolution 2100 - UNSCR. (2013). Available at [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

Nyirabikali, D. (2015). Mali Peace Accord: Actors, issues and their representation | SIPRI. Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

Lyammouri, R. (2018). After Five Years, Challenges Facing MINUSMA Persist. Available at [Accessed 6 Jan. 2020].

Jezequel, J. (2015). Mali's peace deal represents a welcome development, but will it work this time? | Jean-Hervé Jezequel. Available at [Accessed 8 Jan. 2020].