Ruta de navegación

Blogs

UN led vs. non-UN led post-conflict government building

March 28, 2020

WORKING PAPER / María del Pilar Cazali

ABSTRACT

Government building in Africa has been an important issue to deal with after post- independence internal conflicts. Some African states have had the support of UN peacekeeping missions to rebuild their government, while others have built their government on their own without external help. The question this article looks to answer is what method of government building has been more effective. This is done through the analysis of four important overall government building indicators: rule of law, participation, human rights and accountability and transparency. Based on these indicators, states with non-UN indicators have had a more efficient government building especially due to the flexibility and freedom they’ve had to do it in comparison with states with UN intervention due to the UN’s neo-liberal view and their lack of contact with locals.

Download the document [pdf. 431K]

Download the document [pdf. 431K]

The Trump Administration’s Newest Migration Policies and Shifting Immigrant Demographics in the USA

New Trump administration migration policies including the "Safe Third Country" agreements signed by the USA, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras have reduced the number of migrants from the Northern Triangle countries at the southwest US border. As a consequence of this phenomenon and other factors, Mexicans have become once again the main national group of people deemed inadmissible for asylum or apprehended by the US Customs and Border Protection.

![An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov] An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov]](/documents/10174/16849987/migracion-mex-blog.jpg)

▲ An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov]

ARTICLE / Alexandria Casarano Christofellis

On March 31, 2018, the Trump administration cut off aid to the Northern Triangle countries in order to coerce them into implementing new policies to curb illegal migration to the United States. El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala all rely heavily on USAid, and had received 118, 181, and 257 million USD in USAid respectively in the 2017 fiscal year.

The US resumed financial aid to the Northern Triangle countries on October 17 of 2019, in the context of the establishment of bilateral negotiations of Safe Third Country agreements with each of the countries, and the implementation of the US Supreme Court’s de facto asylum ban on September 11 of 2019. The Safe Third Country agreements will allow the US to ‘return’ asylum seekers to the countries which they traveled through on their way to the US border (provided that the asylum seekers are not returned to their home countries). The US Supreme Court’s asylum ban similarly requires refugees to apply for and be denied asylum in each of the countries which they pass through before arriving at the US border to apply for asylum. This means that Honduran and Salvadoran refugees would need to apply for and be denied asylum in both Guatemala and Mexico before applying for asylum in the US, and Guatemalan refugees would need to apply for and be denied asylum in Mexico before applying for asylum in the US. This also means that refugees fleeing one of the Northern Triangle countries can be returned to another Northern Triangle country suffering many of the same issues they were fleeing in the first place.

Combined with the Trump administration’s longer-standing “metering” or “Remain in Mexico” policy (Migrant Protection Protocols/MPP), these political developments serve to effectively “push back” the US border. The “Remain in Mexico” policy requires US asylum seekers from Latin America to remain on the Mexican side of the US-Mexico border to wait their turn to be accepted into US territory. Within the past year, the US government has planted significant obstacles in the way of the path of Central American refugees to US asylum, and for better or worse has shifted the burden of the Central American refugee crisis to Mexico and the Central American countries themselves, which are ill-prepared to handle the influx, even in the light of resumed US foreign aid. The new arrangements resemble the EU’s refugee deal with Turkey.

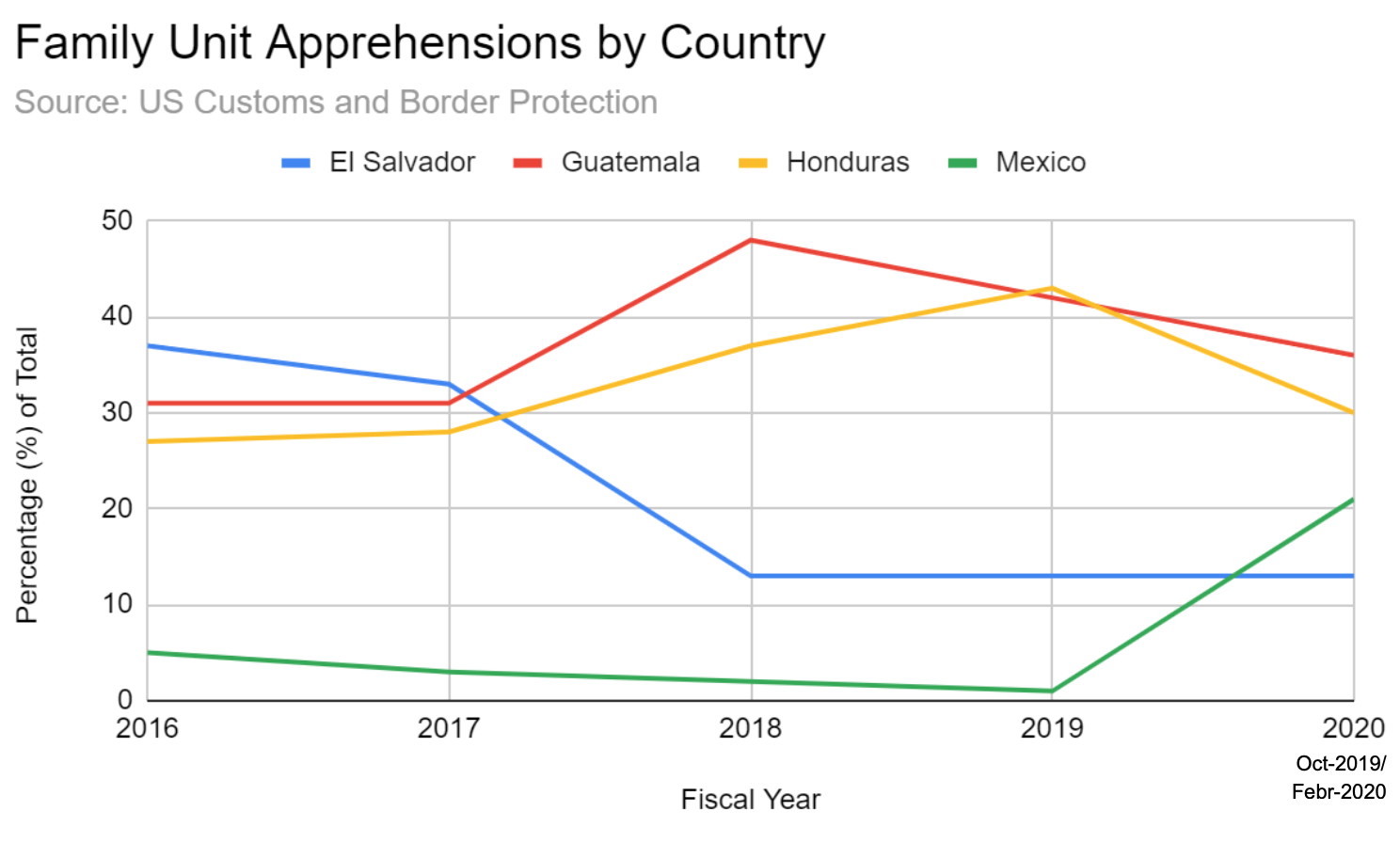

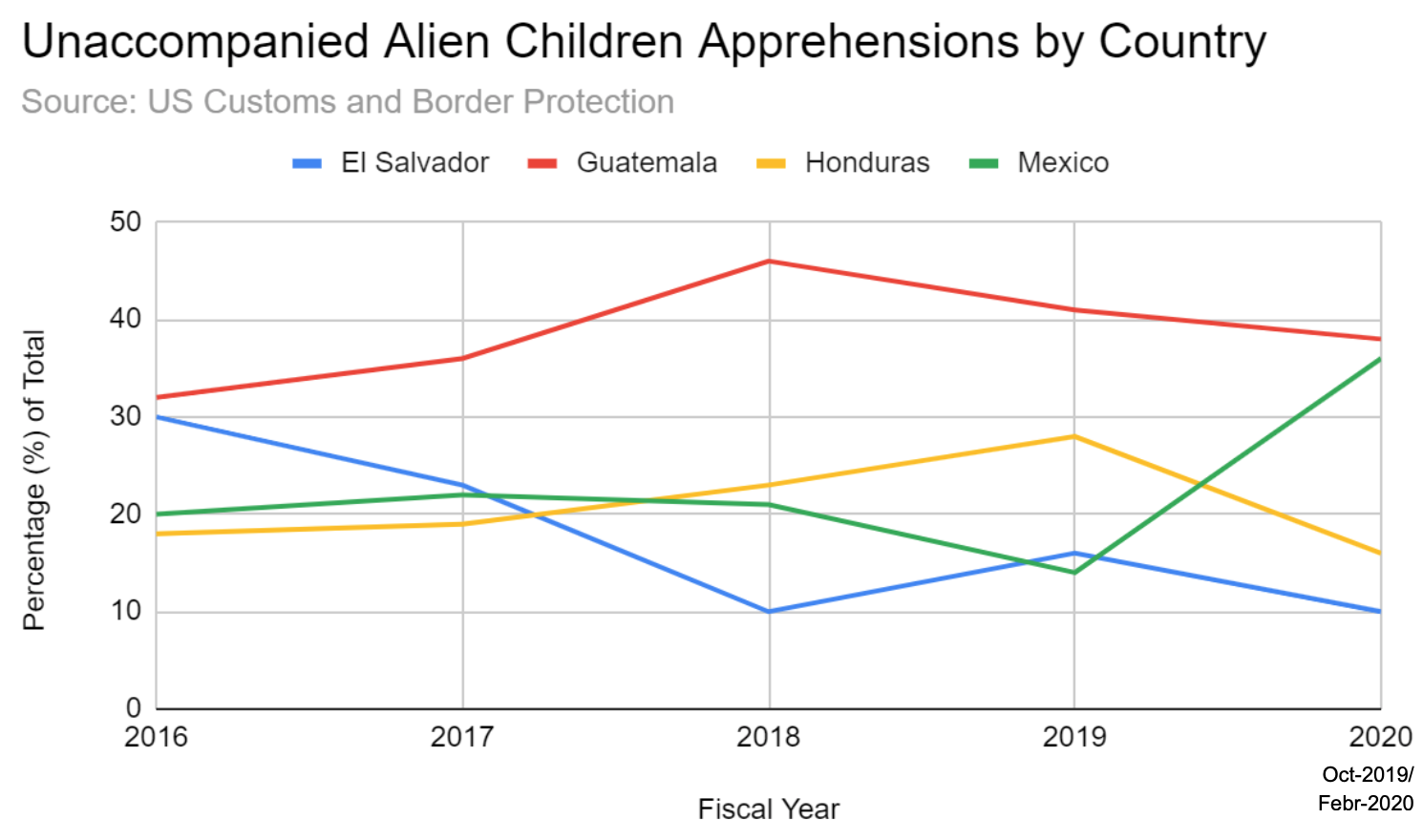

These policy changes are coupled with a shift in US immigration demographics. In August of 2019, Mexico reclaimed its position as the single largest source of unauthorized immigration to the US, having been temporarily surpassed by Guatemala and Honduras in 2018.

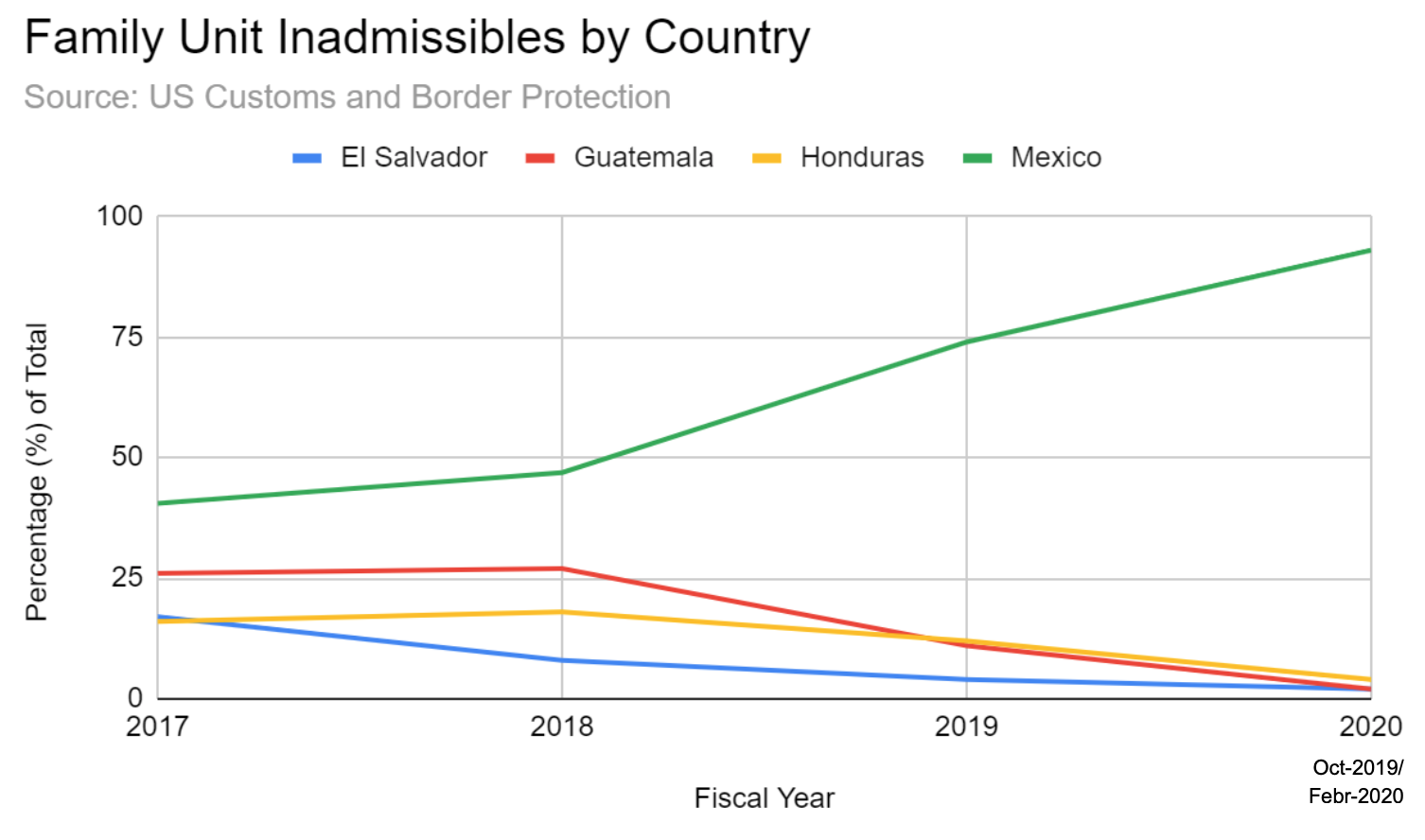

US Customs and Border Protection data indicates a net increase of 21% in the number of Unaccompanied Alien Children from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador deemed inadmissible for asylum at the Southwest US Border by the US field office between fiscal year 2019 (through February) and fiscal year 2020 (through February). All other inadmissible groups (Family Units, Single Adults, etc.) experienced a net decrease of 18-24% over the same time period. For both the entirety of fiscal year 2019 and fiscal year 2020 through February, Mexicans accounted for 69 and 61% of Unaccompanied Alien Children Inadmisibles at the Southwest US border respectively, whereas previously in fiscal years 2017 and 2018 Mexicans accounted for only 21 and 26% of these same figures, respectively. The percentages of Family Unit Inadmisibles from the Northern Triangle countries have been decreasing since 2018, while the percentage of Family Unit Inadmisibles from Mexico since 2018 has been on the rise.

With asylum made far less accessible to Central Americans in the wake of the Trump administration's new migration policies, the number of Central American inadmisibles is in sharp decline. Conversely, the number of Mexican inadmisibles is on the rise, having nearly tripled over the past three years.

Chain migration factors at play in Mexico may be contributing to this demographic shift. On September 10, 2019, prominent Mexican newspaper El Debate published an article titled “Immigrants Can Avoid Deportation with these Five Documents.” Additionally, The Washington Post cites the testimony of a city official from Michoacan, Mexico, claiming that a local Mexican travel company has begun running a weekly “door-to-door” service line to several US border points of entry, and that hundreds of Mexican citizens have been coming to the municipal offices daily requesting documentation to help them apply for asylum in the US. Word of mouth, press coverage like that found in El Debate, and the commercial exploitation of the Mexican migrant situation have perhaps made migration, and especially the claiming of asylum, more accessible to the Mexican population.

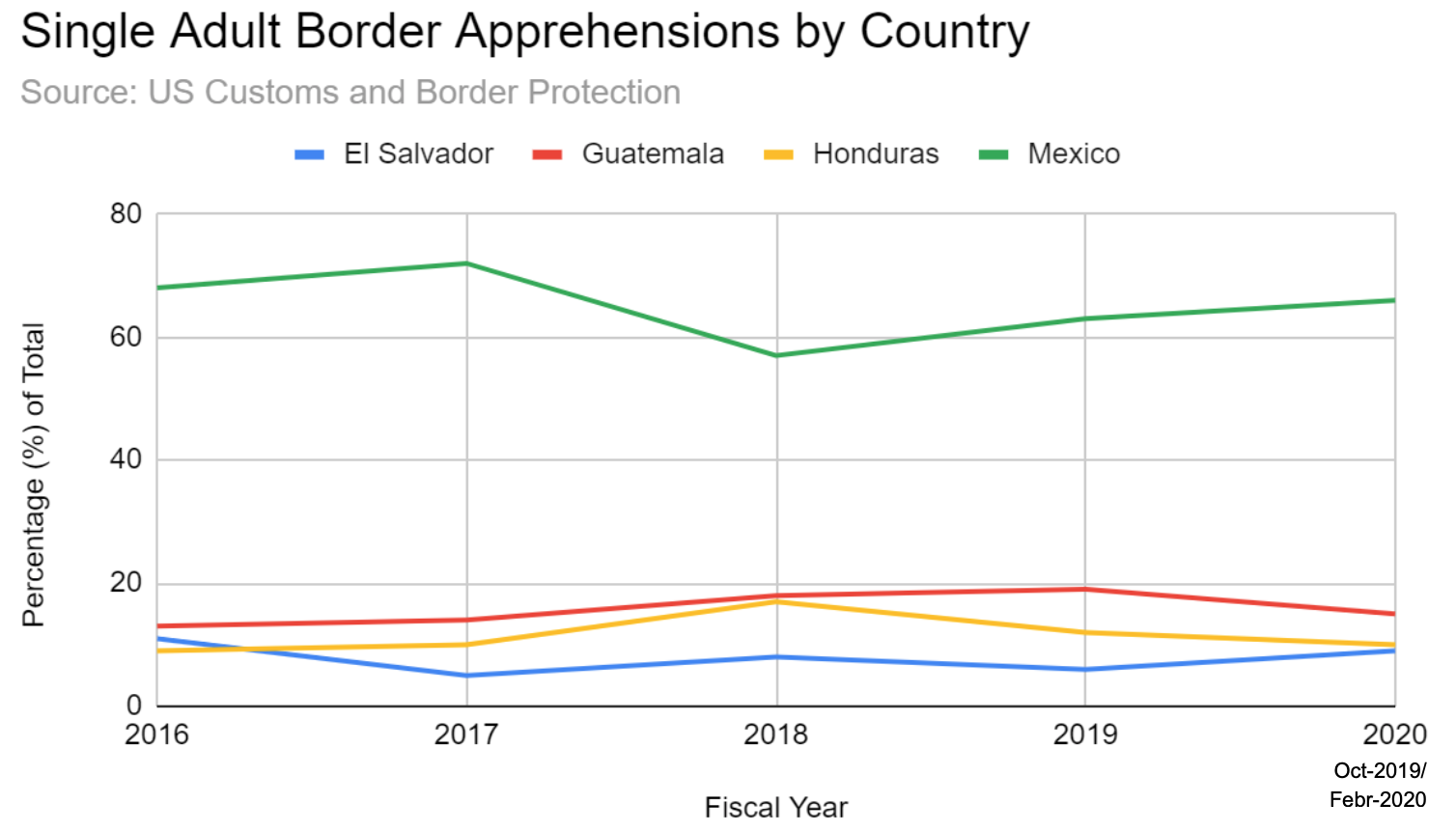

US Customs and Border Protection data also indicates that total apprehensions of migrants from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador attempting illegal crossings at the Southwest US border declined 44% for Unaccompanied Alien Children and 73% for Family Units between fiscal year 2019 (through February) and fiscal year 2020 (through February), while increasing for Single Adults by 4%. The same data trends show that while Mexicans have consistently accounted for the overwhelming majority of Single Adult Apprehensions since 2016, Family Unit and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions until the past year were dominated by Central Americans. However, in fiscal year 2020-February, the percentages of Central American Family Unit and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions have declined while the Mexican percentage has increased significantly. This could be attributed to the Northern Triangle countries’ and especially Mexico’s recent crackdown on the flow of illegal immigration within their own states in response to the same US sanctions and suspension of USAid which led to the Safe Third Country bilateral agreements with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

While the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigration from the Northern Triangle countries has effectively worked to limit both the legal and illegal access of Central Americans to US entry, the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigration from Mexico in the past few years has focused on arresting and deporting illegal Mexican immigrants already living and working within the US borders. Between 2017 and 2018, ICE increased workplace raids to arrest undocumented immigrants by over 400% according to The Independent in the UK. The trend seemed to continue into 2019. President Trump tweeted on June 17, 2019 that “Next week ICE will begin the process of removing the millions of illegal aliens who have illicitly found their way into the United States. They will be removed as fast as they come in.” More deportations could be leading to more attempts at reentry, increasing Mexican migration to the US, and more Mexican Single Adult apprehensions at the Southwest border. The Washington Post alleges that the majority of the Mexican single adults apprehended at the border are previous deportees trying to reenter the country.

Lastly, the steadily increasing violence within the state of Mexico should not be overlooked as a cause for continued migration. Within the past year, violence between the various Mexican cartels has intensified, and murder rates have continued to rise. While the increase in violence alone is not intense enough to solely account for the spike that has recently been seen in Mexican migration to the US, internal violence nethertheless remains an important factor in the Mexican migrant situation. Similarly, widespread poverty in Mexico, recently worsened by a decline in foreign investment in the light of threatened tariffs from the USA, also plays a key role.

In conclusion, the Trump administration’s new migration policies mark an intensification of long-standing nativist tendencies in the US, and pose a potential threat to the human rights of asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border. The corresponding present demographic shift back to Mexican predominance in US immigration is driven not only by the Trump administration’s new migration policies, but also by many other diverse factors within both Mexico and the US, from press coverage to increased deportations to long-standing cartel violence and poverty. In the face of these recent developments, one thing remains clear: the situation south of the Rio Grande is just as complex, nuanced, and constantly evolving as is the situation to the north on Capitol Hill in the USA.

Empresas chinas desarrollan cuatro proyectos mineros en la isla; Trump ofreció comprarla

El deshielo del Ártico abre nuevas rutas marítimas y otorga especial valor a ciertos territorios, como Islandia o especialmente Groenlandia, cuyo enorme tamaño también esconde grandes recursos naturales. Empresas mineras chinas están presentes en la 'Tierra Verde' desde 2008; el gobierno danés ha querido poner freno a un incremento de influencia de Pekín asumiendo directamente la construcción de tres aeropuertos en lugar de que quedaran bajo gestión china. Copenhague teme veladamente que China fomente la independencia de los groenlandeses, mientras la Casa Blanca ha ofrecido comprar la isla, como ya intentara en otros momentos de la historia.

![Población de Oqaatsut, en la costa oriental de Groenlandia [Pixabay] Población de Oqaatsut, en la costa oriental de Groenlandia [Pixabay]](/documents/10174/16849987/groenlandia-blog.jpg)

▲ Población de Oqaatsut, en la costa oriental de Groenlandia [Pixabay]

20 de marzo, 2020

ARTÍCULO / Jesús Rizo Ortiz

Groenlandia es la isla más grande del mundo, con más de 2 millones de kilómetros cuadrados, mientras sus habitantes no llegan a 60.000, lo que la hace el territorio con menor densidad de población del globo. Esta realidad, junto con las riquezas naturales aún por explotar y la ubicación geográfica, otorgan a esta Tierra Verde una gran importancia geoestratégica. Además, el calentamiento global y la puga por el nuevo orden mundial entre EEUU, China y Rusia sitúan a este territorio dependiente de Dinamarca en el centro de las dinámicas geopolíticas, por primera vez en su historia.

Debido al deshielo del Océano Ártico están surgiendo nuevas rutas de comunicación entre los continentes americano, europeo y asiático. Estas vías, aunque en el futuro permanezcan sujetas a limitaciones, están haciéndose cada vez más accesibles y durante más tiempo a lo largo del año. Groenlandia constituye un punto estratégico de control y suministro tanto de la ruta del Norte (la que sigue el contorno norte de Rusia) como del Noroeste (que atraviesa las islas septentrionales de Canadá), no solo en el caso de mercancías y barcos comerciales, sino también en términos de seguridad, ya que el deshielo del océano acorta notablemente las distancias entre los principales actores internacionales.

La posición geográfica de Groenlandia es clave, pero también lo que contiene bajo el hielo que cubre el 77% de su superficie. Se estima que el 13% de las reservas petroleras mundiales se hallan en Groenlandia, así como el 25% de las llamadas tierras raras (neodimio, disprosio, itrio...), que son fundamentales en la producción de nuevas tecnologías.

Interés de China y EEUU

Las perspectivas que abre la mayor posibilidad de navegación a través el Ártico ha llevado a que las potencias árticas elaboraren sus estrategias. Pero también China, interesada en una Ruta de la Seda Polar, ha buscado modos de estar presente el círculo ártico, y ha encontrado en Groenlandia una puerta.

La política exterior de China se concreta en gran medida en la ejecución de proyectos en zonas donde su poderío financiero es necesario, y así lo está haciendo en lugares requeridos de desarrollo como en África y Latinoamérica. Ese tipo de actuación también lo está llevando a cabo en Groenlandia, donde empresas chinas se encuentran presentes desde 2008. Los principales partidos políticos daneses ven con reticencia esa conexión con Pekín, pero la realidad es que mucha de la población groenlandesa, que en más del 80% es de origen inuit, valora positivamente las posibilidades de desarrollo local que abren las inversiones chinas. Esa diferente perspectiva se puso de manifiesto especialmente cuando en 2018 el gobierno de este territorio autónomo promovió tres aeropuertos internacionales (ampliación del de la capital, Nuuk, y construcción en los lugares turísticos de Ilulimat y Qaqortog), lo que en conjunto suponía la mayor contratación de obra pública de su historia. Aunque rápidamente desde China llegó una oferta de la constructora estatal CCCC, finalmente Copenhague decidió aportar fondos públicos daneses y participar en la propiedad de los aeropuertos, dados los recelos que levantaba la iniciativa china.

China está presente, en cualquier caso, en cuatro proyectos previos, relacionados con la minería y gestionados tanto por empresas estatales como privadas, todas ellas siguiendo los propósitos geopolíticos del gobierno chino, cuyo Ministerio de Tecnología de la Información e Industria ha expresado su interés por la actividad en Groenlandia. Esos cuatro proyectos son el de Kvanefjeld para la extracción de tierras raras, financiado principalmente Shenghe Resources; el de Iusa para la extracción de hierro, completamente financiado por General Nice; el de Wegener Halvø para la extracción de cobre, sostenido por Jiangxi Zhongrun tras un acuerdo con Nordic Mining en 2008; y por último, el denominado Citronen Base Metal, a cargo de China Nonferrus Metal Industry’s Foreign Engineering and Construction (NFC).

Estados Unidos no se queda atrás en el interés por Groenlandia. Ya en la década de 1860 el presidente estadounidense Andrew Johnson destacó la importancia de Groenlandia en cuanto a recursos y posición estratégica. Casi un siglo después, en 1946, Harry Truman ofreció al gobierno danés comprar Groenlandia por 100 millones de dólares en oro. Aunque la oferta fue rechazada por Dinamarca, este país sí aceptó el establecimiento en 1951 de una base aérea estadounidense en Thule. Se trata de la base militar más septentrional del mundo, que fue clave en el transcurso de la Guerra Fría y aún hoy sigue funcionando. Esta base supone para EEUU una ventaja no solo ante la apertura comercial de nuevas travesías marítimas, sino ante una hipotética coalición chino-rusa que busque dominar la ruta del Norte. En otras palabras, dada la doble vertiente en la importancia de Groenlandia (recursos naturales y seguridad), se entiende que alguien tan poco convencional como Donald Trump haya vuelto a sugerir la posibilidad de comprar la inmensa isla, algo que Copenhague ha declinado.

![Proyección de rutas a través del Ártico; la fila superior corresponde al deshielo que podría producirse con bajas emisiones, la inferior en el caso de altas emisiones [Arctic Council] Proyección de rutas a través del Ártico; la fila superior corresponde al deshielo que podría producirse con bajas emisiones, la inferior en el caso de altas emisiones [Arctic Council]](/documents/10174/16849987/groenlandia-mapa.jpg)

Proyección de rutas a través del Ártico; la fila superior corresponde al deshielo que podría producirse con bajas emisiones, la inferior en el caso de altas emisiones [Arctic Council]

En el centro de un ‘Great Game’

Al margen de la inviabilidad hoy de una operación de ese tipo sin tener en cuenta, entre otras cosas, la voluntad de la población, es cierto que está teniendo lugar un Great Game entre los principales actores internacionales por contar con Groenlandia entre sus cartas geoestratégicas.

1) Estados Unidos ya cuenta con presencia militar en Groenlandia, así como con buenas relaciones con Dinamarca e Islandia, ambos miembros de la OTAN, por lo que el control del estrecho de Dinamarca está garantizado, así como del espacio entre Groenlandia, Islandia y el Reino Unido (conocido como GIUK Gap), que comunica el Ártico con el Atlántico Norte. No obstante, Washington deberá cambiar su estrategia si quiere hacerse con el control de Groenlandia, comenzando por mejorar sus relaciones con el gobierno danés y financiando proyectos en la isla.

2) Aunque sin protagonismo en relación a Groenlandia, Rusia goza de preeminencia en toda la región ártica. Es, con diferencia, el país con más presencia militar en la zona, habiendo reutilizado algunas de las instalaciones soviéticas. Es la potencia hegemónica en toda la ruta Norte, considerada por el Kremlin como la principal vía de comunicación nacional. Dado el imperio absoluto de Rusia sobre esta vía, el hielo que todavía la cubre durante gran parte del año, y el control de los EEUU en su vertiente atlántica, esta Ruta no supondrá (al menos en principio) una alternativa real y rentable al estrecho de Malaca, para desasosiego de China.

3) China presentó en 2018 su libro blanco sobre su política para el Ártico, en el que se definió como “potencia casi ártica”. De momento, se ha fijado en Groenlandia como punto fundamental en su Ruta de la Seda Polar. La ruta del Norte acortaría alrededor de una semana el tiempo de transporte entre los puertos asiáticos y europeos y sería una alternativa más que necesaria al estrecho de Malaca. En la gran isla se ha centrado Hasta ahora en la extracción de recursos, siguiendo su particular y cauto modus operandi. Además, los fondos chinos suponen para los groenlandeses una alternativa a la dependencia absoluta de Dinamarca, lo que adicionalmente favorece las pretensiones nacionalistas de la isla.

Los cambios, aunque significativos en algunos casos, no modificarán sustancialmente las corrientes comerciales entre los tres países

El nuevo Tratado de Libre Comercio de Estados Unidos, Canadá y México ha quedado listo para su aplicación, tras la ratificación llevada a cabo en los congresos de los tres países. La revisión del anterior tratado, que entró en vigor en 1994, fue reclamada por Donald Trump en su llegada a la Casa Blanca, alegando el déficit comercial generado para EEUU en relación a Canadá y especialmente a México. Aunque se han introducido algunas correcciones significativas, siguiendo los principales planteamientos estadounidenses, no parece que el revisado acuerdo vaya a modificar sustancialmente las corrientes comerciales entre los tres países.

![Los presidentes Peña Nieto, Trump y Trudeau firman el acuerdo de libre comercio en noviembre de 2019 [US Gov.] Los presidentes Peña Nieto, Trump y Trudeau firman el acuerdo de libre comercio en noviembre de 2019 [US Gov.]](/documents/10174/16849987/tmec-blog-pyn6UhDC.jpg)

▲ Los presidentes Peña Nieto, Trump y Trudeau firman el acuerdo de libre comercio en noviembre de 2019 [US Gov.]

ARTÍCULO / Marcelina Kropiwnicka

El primero de enero de 1994 entró en vigor el Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte (TLCAN o su versión en inglés, NAFTA). Más de veinte años después y bajo la administración del presidente Donald Trump, los tres países socios abrieron un proceso de revisión del acuerdo, ahora denominado Tratado de Libre Comercio de Estados Unidos, Canadá y México (al que cada país, poniéndose por delante, le ha dado unas siglas distintas: los mexicanos lo llaman T-MEC o TMEC, los estadounidenses USMCA y los canadienses CUSMA).

El texto del TMEC (sus siglas en español) finalmente ratificado por los tres países es coherente en general con el antiguo TLCAN. No obstante, hay distinciones particulares. Así, incluye normas de origen más estrictas en los sectores automovilístico y textil, un requisito de contenido de valor laboral actualizado en el sector del automóvil, un mayor acceso de Estados Unidos a los mercados gestionados por la oferta canadiense, disposiciones novedosas relacionadas con los servicios financieros y una especificación sobre el establecimiento de acuerdos de libre comercio con economías que no son de mercado. El objetivo conjunto es incentivar la producción en América del Norte.

Novedades negociadas en 2017–2018

Las tres partes comenzaron la negociación en verano de 2017 y al cabo de algo más un año cerraron un acuerdo, firmado por los presidentes de los tres países en noviembre de 2018. Las principales novedades introducidas hasta entonces fueron las siguientes:

1) El acuerdo revisa el porcentaje del contenido de valor regional (RVC) referido a la industria del automóvil. En el TLCAN se establecía que al menos el 62,5% de un automóvil debía estar hecho con piezas procedentes de América del Norte. El TMEC eleva el porcentaje al 75% con la intención de fortalecer la capacidad de fabricación de los países y aumentar la fuerza de trabajo en la industria automotriz.

2) En esta misma línea, para apoyar el empleo en América del Norte, el acuerdo contiene nuevas reglas de origen comercial para impulsar los salarios más altos al obligar a que el 40-45% de la fabricación de automóviles sea realizada por trabajadores que ganen al menos 16 dólares por hora de promedio para el año 2023; eso es aproximadamente tres veces el pago que normalmente recibe hoy un operario mexicano.

3) Aparte de la industria automotriz, el mercado de productos lácteos se abrirá para asegurar un mayor acceso de los productos lácteos de EEUU, una demanda clave para Washington. En la actualidad, Canadá tiene un sistema de cuotas nacionales que se establecieron para proteger a sus agricultores de la competencia extranjera; sin embargo, en virtud del nuevo acuerdo del TMEC, los cambios permitirán a Estados Unidos exportar hasta el 3,6% del mercado de productos lácteos de Canadá, lo que supone un aumento del 2,6% con respecto a la disposición original del TLCAN. Otro logro clave para Trump fue la negociación de la eliminación por parte de Canadá de lo que se conoce como sus clases de leche 6 y 7.

4) Otro aspecto nuevo es la cláusula de extinción. El TLCAN tenía una cláusula de extinción automática o una fecha de finalización predeterminada del acuerdo, lo que significaba que cualquiera de las tres partes podía retirarse del acuerdo, previo aviso de seis meses sobre el retiro; si esto no ocurría, el acuerdo se mantenía indefinido. Sin embargo, el TMEC prevé una duración 16 años, con la opción de reunirse, negociar y revisar el documento después de seis años, así como con la posibilidad de renovar el acuerdo una vez transcurridos los 16 años.

5) El pacto de los tres países también incluye un capítulo sobre el trabajo que ancla en el núcleo del acuerdo las obligaciones laborales, haciendo más exigente su ejecución.

Reformas en México

Precisamente para hacer más creíble ese último punto, los negociadores de EEUU y Canadá exigieron que México hiciera cambios en sus leyes laborales para acelerar el proceso de aprobación y ratificación del TMEC por parte de los legisladores de Washington y Ottawa. Los líderes de la Cámara de Representantes de EEUU habían dudado de la capacidad de México para cumplir específicamente con los puntos de derechos laborales del acuerdo. Uno de los principales objetivos del presidente Trump en la renegociación era asegurar a los trabajadores estadounidenses que se superaría la situación de competencia desigual.

El presidente mexicano, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, envió una carta al Congreso de EEUU garantizando la implementación de un plan de cuatro años para asegurar el logro de los derechos laborales adecuados. López Obrador se comprometió a un desembolso de 900 millones de dólares en los siguientes cuatro años para cambiar el sistema de justicia laboral y asegurar que las disputas entre trabajadores y empleadores se resuelvan de manera oportuna. México también ha invertido en la construcción de un Centro Federal de Conciliación y Registro Laboral, donde los conflictos laborales serán abordados antes de su audiencia en la corte.

Obrador mostró su compromiso con las reformas laborales asegurando al menos un aumento del 2% del salario mínimo en México. Lo más notable es que la exigencia del voto directo de los líderes sindicales modificará el funcionamiento de las organizaciones de trabajadores. Con elecciones directas, las decisiones sobre los convenios colectivos serán más transparentes. El plan mexicano para mejorar el entorno laboral comenzará en 2020.

Novedades de 2019 para facilitar la ratificación

Ante las demandas planteadas en el Congreso de EEUU, sobre todo por la mayoría demócrata, para ratificar el tratado, los negociadores procedieron a dos revisiones importantes del TCLAN. Una de ellas dirigida principalmente a revisar una amplia cantidad de disposiciones relativas a la propiedad intelectual, los productos farmacéuticos y la economía digital:

6) El capítulo dedicado a los derechos de propiedad intelectual busca responder a inquietudes de EEUU para impulsar la innovación, generar crecimiento económico y respaldar puestos de trabajo. Por primera vez, según el representante de Comercio de Estados Unidos, las adiciones incluyen: normas estrictas contra la elusión de las medidas de protección tecnológica de música, películas y libros digitales; una fuerte protección para la innovación farmacéutica y agrícola; una amplia protección contra el robo de secretos comerciales, y autoridad de oficio para que los funcionarios detengan mercancías presuntamente falsificadas o pirateadas.

7) También se ha incluido un nuevo capítulo sobre comercio digital que contiene controles más estrictos que cualquier otro acuerdo internacional, lo que consolida los cimientos para la expansión del comercio y la inversión en esferas en las que EEUU tiene una ventaja competitiva.

8) El redactado final elimina una garantía de 10 años de protección de la propiedad intelectual para los medicamentos biológicos, que son algunos de los medicamentos más caros del mercado. Asimismo, suprime conceder tres años adicionales de excluvisidad de propiedad intelectual para medicamentos a los que se encuentre un nuevo uso.

Un segundo grupo de cambios de última hora hace referencia a mayores protecciones medioambientales y laborales:

9) Lo relativo al medio ambiente cubre 30 páginas, que esbozan las obligaciones para combatir el tráfico de vida silvestre, madera y pescado; fortalecer la aplicación de la ley para detener dicho tráfico, y abordar cuestiones ambientales críticas como la calidad del aire y los residuos marinos. Entre las nuevas obligaciones figuran: la protección de diversas especies marinas, la implantación de métodos adecuados para las evaluaciones de impacto ambiental, y la adecuación a las obligaciones de siete acuerdos ambientales multilaterales. En particular, México está de acuerdo en mejorar la vigilancia para poner fin a la pesca ilegal, y los tres países acuerdan dejar de subvencionar la pesca de especies sobreexplotadas. Para aumentar la responsabilidad ambiental, los demócratas de la Cámara de Representantes de EEUU instaron a que se cree un comité interinstitucional de supervisión. Sin embargo, el tratado no en asuntos de cambio climático.

10) Para asegurar que México cumple lo prometido respecto al ámbito laboral, los demócratas de la Cámara de Representantes forzaron la creación de un comité interagencial que monitoree la implementación de la reforma laboral de México y el cumplimiento de las obligaciones laborales. A pesar del nuevo y único requisito de la ‘LVC’, una regla de contenido de valor laboral, todavía será difícil imponer un salario mínimo a los fabricantes de automóviles mexicanos. No obstante, los demócratas estadounidenses esperan que la condición obligue a los fabricantes de automóviles a comprar más suministros de Canadá o EEUU o que haga que los salarios de los fabricantes de automóviles en México aumenten.

El acuerdo finalmente ratificado reemplazará el que está vigor desde hace 25 años. En general el paso del TLCAN al TMEC no debería causar un efecto drástico en los tres países. Es un acuerdo progresivo que supondrá ligeros cambios: ciertas industrias se verán afectadas, como la automotriz y la lechera, pero en una pequeña proporción. A largo plazo, dadas las modificaciones introducidas, los salarios debieran aumentará en México, lo que disminuiría la migración mexicana a EEUU. Las empresas se verán afectadas a largo plazo, pero con planes de respaldo y nuevos rediseños es de esperar que el proceso de transición sea suave y mutuamente beneficioso.

▲ A picture of Vladimir Putin on Sputnik's website

March 12, 2020

ESSAY / Pablo Arbuniés

A new form of power

Russia’s growing influence in African countries and public opinion has often been overlooked by western democracies, giving the Kremlin a lot of valuable time to extend its influence on the continent.

Until very recently, western democracies have looked at influence efforts from authoritarian countries as nothing more than an exercise of soft power. Joseph S. Nye defined soft power as a nation’s power of attraction, in contrast to the hard power of coercion inherent in military or economic strength (Nye 1990). However, this influence does not fit the common definition of soft power as ‘winning hearts and minds’. In the last years China and Russia have developed and perfected extremely sophisticated strategies of manipulation aimed towards the civil population of target countries, and in the case of Russia the role of Russia Today should be taken as an example.

These strategies go beyond soft power and have already proved their effectiveness. They are what the academia has recently labelled as sharp power (Walker 2019). Sharp power aims to hijack public opinion through disinformation or distraction, being an international projection of how authoritarian countries manipulate their own population (Singh 2018).

Sharp power strategies are being severely underestimated by western policy makers and advisors, who tend to focus on more classical conceptions of the exercise of power. As an example, the “Framework document” issued by the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies on Russia-Africa relations (Mora Tebas 2019). The document completely ignores sharp power, labelling Russian interest in communication markets as no more than regular soft power without taking into consideration de disinformative and manipulative nature of these actions.

A growing interest in Africa

Over the past 20 years, many international actors have shifted their interest towards the African continent, each in a different way.

China has made Africa a mayor geopolitical target in recent years, focusing on economic investments for infrastructure development. Such investments can be noticed in the Ethiopian dam projects such as the Gibe III, or in the Entebbe-Kampala Expressway in Uganda.

This could be considered as debt-trap diplomacy, as China uses infrastructure investments and development loans to gain leverage over African countries. However, there is also a key geopolitical interest, especially in those countries with access to the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, due to the One Belt One Road Initiative. This project requires a net of seaports, where Kenya, and specifically the port of Lamu, could play a key role becoming a hub for trade in East Africa (Hurley, Morris and Portelance 2019).

Also, Chinese investments are attractive for African countries because they do not come with prerequisites of democratization or transparent administration, unlike those from western countries.

Yet, even though both China and Russia use sharp power as part of their foreign policy strategies, China does barely use it in Africa, since its interests in the continent are more economic than political. This is based on the view that China is more keen to exploit Africa’s natural resources (Mlambo, Kushamba y Simawu 2016) than anything else.

On the other hand, Russia has both economic and military interests in the region. This is exemplified by the case of Sudan, where in addition to the economic interest in natural resources, there is also a military interest in accessing the Red Sea. In order to achieve these goals, the first step is to grant stability in the country, and it can be achieved through ensuring that public opinion supports the government and accepts Russian presence.

The idea of a Russian world—Russkiy Mir—has grown under Putin and is key to understanding the country’s soft and sharp power strategies. It consists on the expansion of power and culture using any means possible in order to regain the lost superpower status.

However, this approach must not be seen only as a nostalgic push to regain status, but also from a purely pragmatic point of view, since economic and practical factors have “pushed aside ideology” in the competition against the West (Warsaw Institute 2019).

The recent Russia-Africa Summit (23-24 October 2019), that took place in Sochi, Russia, proves how Russia has pivoted towards Africa in recent years, offering infrastructure, energy and other investments as well as arms deals and different advisors. The outcome of this pivoting is being quite beneficial for Moscow in strategic terms.

The Kremlin’s interest in Africa was not remarkable until the post Crimea invasion. The economic sanctions imposed after the occupation of Crimea forced Russia to look further abroad for allies and business opportunities. For instance, as part of this policy there a more robust involvement of Russia in Syria.

The Russian strategy for the African continent involves benefiting favourable politicians through political and military advisors and offering control on media influence (Warsaw Institute 2019). In exchange, Russia looks for military and energy supply contracts, mining concessions and infrastructure building deals. Moreover, on a bigger picture, Russia—as well as China—aims to reduce the influence of the US and former colonial powers France and the UK.

Leaked documents published by The Guardian (Harding and Buerke 2019), show this effort to gain influence on the continent, as well as the strategies followed and the degree of cooperation with the different powers—from governments to opposition groups or social movements.

However, the growth of Russia’s influence in Africa cannot be understood without the figure of Yevgeny Prigozhin, an extremely powerful oligarch which, according to US special counsel Robert Mueller, was critical to the social media campaign for the election of Donald Trump in 2016. He is also linked to the foundation of the Wagner group, a private military contractor present among other conflicts in the Syrian war.

Prigozhin, through a network of enterprises known as ‘The Company’ has been for long the head of Putin’s plans for the African continent, being responsible of the growing number of Russian military experts involved with different governments along the continent, and now suspected to lead the push to infiltrate in the communication markets.

Between 100 and 200 spin doctors have already been sent to the continent, reaching at least 10 different countries (Warsaw Institute 2019). Their focus is on political marketing and specially on social media, with the hope that it can be as influential as in the Arab Springs.

Main targets

Influence in the media is one of the key aspects of Russia’s influence in Africa, and the main targets in this aspect are the Central African Republic, Madagascar, South Africa and Sudan. Each of these countries has a potential for Russian interests, and is targeted on different levels of cooperation, from weapons deals to spin doctors (Warsaw Institute 2019), but all of them are targets for sharp power strategies.

However, it is hard for a foreign government to directly enter the communication markets of another country without making people suspicious of its activities, and that is where The Company plays its role. Through it, pro-Russian editorial lines are fed to the population of the target states by acquiring already existing media platforms—such as newspapers or television and radio stations—or creating new ones directly under the supervision of officials of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, this ensures that the dominant frames fit Russia’s interests and that of its allies.

Also, the presence of Russian international media is key to its sharp power. Russia Today and Sputnik have expanded their reach by associating with local entities in Eritrea, Ivory Coast, etc. Russian radio services have been expanded to Africa as well as a key factor in both soft and sharp power.

Finally, social media are a great way of distributing disinformation, given its global reach and the insufficient amount of fact-checkers devoted to this area. There, not only Russian media can participate but also bots and individual accounts are at the service of the Kremlin’s interests.

Madagascar

Although Madagascar is viewed by the Kremlin as a high cooperation partner, it doesn’t seem to have much to offer in geopolitical terms other tan mining concessions for Russian companies. Therefore, Russian presence in Madagascar was widely unexpected.

During the May 2019 election, Russia backed six different candidates, but none of them won. In the final stages of the campaign, the Kremlin changed its strategy and backed the expected and eventual winner, Andry Rajoelina (Allison 2019). This could be considered a fiasco and ignored because of the disastrous result, but there is a key aspect that shows how Russia is trying to shape public opinion across the continent.

Although political advisors and spin doctors were only one part of the plan, Russia managed to produce and distribute the biggest mass-selling newspaper along the country with more than two million copies every month (Harding and Buerke 2019). Though it did not seem to have any major impact on the short term, it could be an important asset for shaping public opinion on the long run.

Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) is of major geopolitical relevance in the whole of the African continent. Due to its location as well as its cultural and ethnic features, it is viewed by the Kremlin as the gate to the whole continent. It is the zone of transition between the Muslim north of the continent and the Christian south (Harding and Buerke 2019).

Given the complicated situation and the context of the ongoing civil war, it can be considered as an easy target for foreign powers. This is mainly due to the power structures being weakened by the war. Russia is part of the UN peacekeeping mission in the CAR, in a combination of soft and hard power. Also, a Russian training centre is operative in the country, and both Moscow and Bangui are open to the inauguration of a Russian military base.

Russia played a key role in the peace deal of February 2019, and since 2017 Valery Zakharov, a former Russian intelligence official, has been an adviser to CAR’s president. All of this, if the peacekeeping operations are successful, would lead to an immense political debt in favour of the Kremlin.

The mineral richness of the CAR is another asset to consider due to the reserves of gold and high-quality diamonds. Also, there is a big business opportunity in rebuilding a broken country, and Russian oligarchs and businessmen would certainly be interested in any public contracts regarding this matter.

In the CAR, Russia exerts sharp power not only through social media, but also through two print publications and a radio station, which still have limited influence (Harding and Buerke 2019). Through such means, Russia is consistently feeding its frames narratives to a disoriented population, which given the unstable context, would be an easy target to manipulate. Moreover, the possibility to create a favourable dominant post conflict narrative would render public opinion more likely to accept Russian presence in the future.

Sudan

Sudan is of major geostrategic importance for Russia among many other actors. For long time both countries have had economic, political and military relations, leading to Sudan being considered by the Kremlin as a level 5 co-operator, the highest possible (Harding and Buerke 2019). This relation is enforced by Sudan’s constant claims of aggressive acts by the United States, for which it demands Russia’s military assistance.

Also, Sudan is rich in uranium, bearing the third biggest reserves in the world. Uranium is a key raw material to build a major power nowadays, and Russia is always keen on new sources of uranium to bolster its nuclear industry.

Moreover, Sudan is key in regional and global geopolitics because it offers Russia a possibility to have a military base with access to the Red Sea. Given the amount of trade routes that go through its waters, the Kremlin would be very keen to have said access. Many other powers have shown interest in this area, such as the gulf States, or China with its base in Djibouti being operative since 2017.

For all these reasons. Sudan is a very special element in Russia’s plans, and thus its level of commitment is greater than in other countries. The election to take place on April 2020 could be considered as one of the most important challenges for democracy in the short term. Russia is closely monitoring the situation in order to draw an efficient plan of action.

Before the end of Omar al-Bashir’s presidency, Russia and Sudan enjoyed good relationship. Russian specialists had prepared reforms in economic and political matters in order to ensure the continuity in power of Bashir, and his fall was a blow to these plans.

However, Russia will devote many resources to amend the situation in the Sudan parliamentary and presidential election, that will take place in April 2020. In a ploy to maintain power, Al Bashir mirrored the measures employed against opposition protesters in Russia. These tactics consist of using disinformation and manipulated videos in order to portray any opposition movement as anti-Islamic, pro-Israeli or pro-LGBT. Given the fact the core of Sudan’s public opinion is mostly conservative and religious, Russia’s plan consists on manipulating it towards its desired candidate or candidates (Harding and Buerke 2019).

In order to ensure that the Russian framing was dominant, social media pages like Radio Africa’s Facebook page or Sudan Daily were presented like news pages, while being in fact part of a Russian-backed influence network in central and northern Africa (Alba and Frenkel 2019). The information shown has been supportive of whatever government is in power, and critical of the protesters (Stanford Internet Observatory 2019), which shows that Russia’s prioritary interest is a stable government and weak protesters.

Another key part of the strategy has been pressuring the government to increase the cost of newsprint to limit the possibilities of countering the disinformation distributed with the help pf Russian advisors (Harding and Buerke 2019). The de-democratization of information can prove to be very effective, even more taking into account the fact that social media is not as powerful in Sudan as it is in western countries, so owning the most popular means of communication allows to create a dominant frame and impose it to the population without them even noticing.

South Africa

The economic context of South Africa, with a large economy, a rising middle class and a good market overall, is quite interesting for business and could be one of the reasons why Russia has such an interest in the country. Also, South Africa can be seen as an economic gateway to the southern part of the African continent.

South Africa is a key country for the global interest of Russia. Not only for its mineral richness and business opportunities, but mainly for its presence in BRICS. Russia attempts to use BRICS as a global counterbalance in a US dominated international landscape.

Russia is interested in selling nuclear technology to its allies, and South Africa is no exception. The presence of South Africa in BRICS is key to understand why such a deal would be so interesting for Russia. BRICS may not offer the possibility to create a perfect counter-balance for western powers, mainly due to the unsurpassable discrepancies among the involved countries, but its ability to cooperate comprehensively on limited shared projects and objectives can be of critical relevance (Salzman 2019).

The presence in the country of Afrique Panorama and AFRIC (Association for Free Research and International Cooperation), shows how Russia attempts to exert its influence. Both pages are linked to Prigozhin, but they are disguised as independent. AFRIC was involved in the elections of Zimbabwe, South Africa, Madagascar and DRC (Grossman, Bush y Diresta 2019).

In fact, if public opinion could be shaped in order to make Russia’s interests like nuclear cooperation acceptable by South Africa, the main obstacle would be surpassed, and a comprehensive plan of cooperation would be in play sooner than later.

The elections of May 2019 were one of the main priorities for Russia. The election saw Cyril Ramaphosa elected, as successor of Jacob Zouma. Ramaphosa is known to have openly congratulated Nicolás Maduro for his second inauguration and holds good relations with Vietnam. This are indicators of a willingness to have good relations even with anti-western powers, which is of big interest for the Kremlin. Furthermore, he has a vast business experience, being the architect of the most powerful trade union in the country among other achievements and initiatives, which would see him open to strike deals with Russian oligarchs in the mineral or energetic fields.

All this considered, South Africa is of extreme relevance for Russia, and thus its efforts to be able to shape public opinion. This could be used to favour the implementation of nuclear facilities as well as electing favourable politicians, creating a political debt to be exploited someday. For now, any activity has been limited to tracking and getting to understand public opinion. However, the creation of new media under some form of control by the Kremlin is one of the priorities for the coming years (Harding and Buerke 2019), and could prove a very valuable asset if it’s successfully achieved. Also, despite what was said in the case of Sudan, the importance of social media is not to be forgotten or underestimated, especially given the advantage of English being an official language in the country.

The bigger picture

From a more theorical point of view, that of the Flow and Contra-flow paradigm, Russia attempts to set the political agenda through mass media control, as well as impose its own frames or those that benefit its allies. Also, given the proportions of the project, we could talk about an attempt to go back to the cultural imperialism doctrines, where Russia attempts to pose its narrative as a counterflow of the western narratives. This was mainly seen during the cold war, when global powers attempted to widely spread their own narratives through controlling said information flows, arguably as a form of cultural imperialism.

This can be seen as an attempt to counterbalance the power of the US and western powers by attempting to shift African countries towards non-western actors. And African countries may be interested in this idea, since being the centre of the competition could mean better deals and business opportunities or investments being offered to them.

It would be a mistake to think that Russia’s sharp power in Africa is just a tool to help political allies get to power or maintain it. Beyond that, Russia monitors social conflicts and attempts to intensify them in order to destabilize target countries or exterior powers (Alba and Frenkel 2019). Such is the case in Comoros, where Prigozhin employees were tasked to explore the possibilities of intensifying the conflict between the local government and the French administration (Harding and Buerke 2019). Again on a broader picture of things, the attempt to develop an African self-identity through the use of sharp power looks to reduce the approval of influence of western democracies on the continent, thus creating a context ideal for bolstering dependence on the Russian administration either through supply contracts or political debt.

In conclusion, the recent growth of Russia’s soft and above all sharp power in Africa could potentially be one of the political keys in the years to follow, and it is not to be overlooked by western democracies. Global media, supranational entities and public administrations should put their efforts on providing civil society with the tools to avoid falling for Russia’s manipulative tactics and serve as guarantors of democracy. The most immediate focus should be on the US 2020 election, since the worst-case scenario is that the latest exercises of Russia’s sharp power in Africa are a practice towards a new attempt at influencing the US presidential election in 2020.

REFERENCES

Alba, Davey, and Sheera Frenkel. 2019. “Russia Tests New Disinformation Tactics in Africa to Expand Influence.” The New York Times, 30 October.

Allison, Simon. 2019. “Le retour contrarié de la Russie en Afrique.” Courrier international, 5 August.

Ashraf, Nadia, y Jeske van Seters. 2020. «Africa and EU-Africa partnership insights: input for estonia’s new africa strategy.» ECDPM.

Grossman, Shelby, Daniel Bush, y Renée Diresta. 2019. «Evidence of Russia-Linked Influence Operations in Africa.»

Harding, Luke, and Jason Buerke. 2019. “Leaked documents reveal Russian effort to exert influence in Africa.” The Guardian, 11 June. Accessed November 25, 2019.

Hurley, John, Scott Morris, y Gailyn Portelance. 2019. «Examining the debt implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a policy perspective.» Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development (EnPress Publisher) 3 (1): 139.

Madowo, Larry. 2018. Should Africa be wary of chinese debt.

Mlambo, Courage, Audrey Kushamba, y More Blessing Simawu. 2016. «China-Africa Relations: What Lies Beneath?» Chinese Economy (Routledge) 49 (4): 257-276.

Mora Tebas, Juan A. 10/2019. http://www.ieee.es/. 2019. ««Rusiáfrica»: el regreso de Rusia al «gran juego» africano.» Documento Marco IEEE. Último acceso: 30 de Nov de 2019. http://www.ieee.es/.

Nye, Joseph. 1990. Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power. London: Basic Books.

Salzman, Rachel S. 2019. Russia, BRICS, and the disruption of global order. Georgetown University Press.

Singh, Mandip. 2018. “From Smart Power to Sharp Power: How China Promotes her National Interests .” Journal of Defence Studies.

Standish, Reid. 2019. Putin Has a Dream of Africa. Foreign Policy.

Stanford Internet Observatory. 2019. «Evidence of Russia-Linked Influence Operations in Africa.»

Walker, C. and Ludwig, J. 2019. «The Meaning of Sharp Power.» Foreign Affairs.

Warsaw Institute. 2019. “Russia in Africa: weapons, mercenaries, spin doctors.” Strategic report, Warsaw.

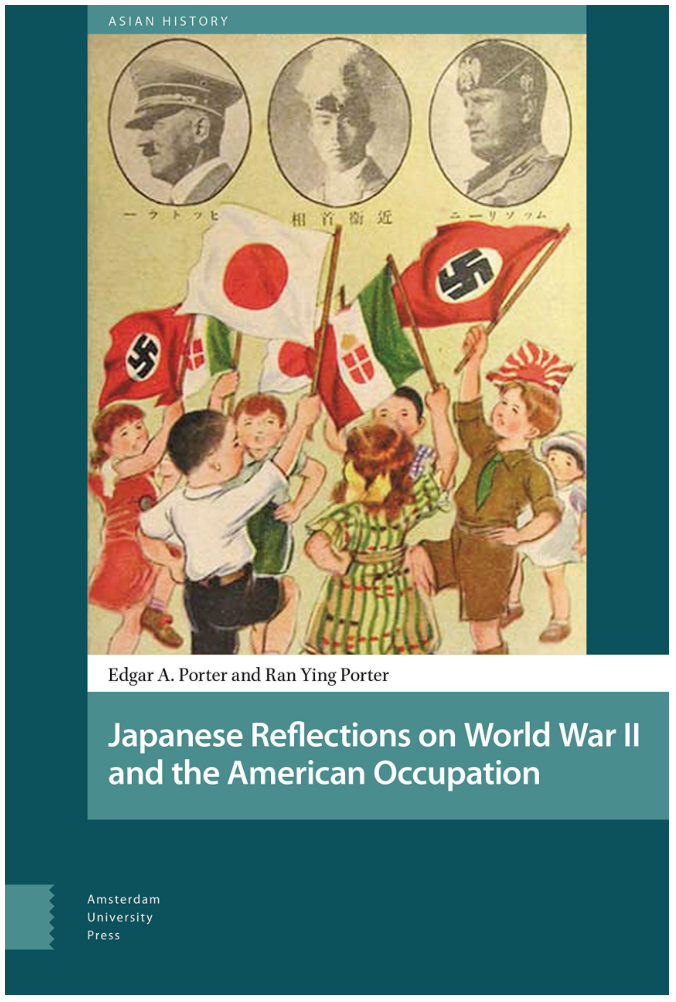

[Edgar A. Porter & Ran Yin Porter, Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation. Amsterdam University Press. Amsterdam, 2017. 256 p.]

REVIEW / Rut Natalie Noboa Garcia

World War II has provided much inspiration for an entire genre of literature. However, few works fail to capture Asian perspectives on the beginning, development, end, and consequences of World War II. Additionally, the attitude and outlooks of defeated parties are often left out of popularized discussions of conflicts. Because of these two factors, Japanese perspectives during the war and occupation have often served as only minor discussions in World War II literary work.

World War II has provided much inspiration for an entire genre of literature. However, few works fail to capture Asian perspectives on the beginning, development, end, and consequences of World War II. Additionally, the attitude and outlooks of defeated parties are often left out of popularized discussions of conflicts. Because of these two factors, Japanese perspectives during the war and occupation have often served as only minor discussions in World War II literary work.

This sets the stage for Edgar A. Porter and Rin Ying Porter’s Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation, which presents the experiences of ordinary Japanese citizens during the period. The book specifically focuses on the rural Oita prefecture, located on the eastern coast of the island of Kyushu, a crucial yet critically unacknowledged place in Japan’s role in World War II. Hosting the Imperial Japanese Navy base that served as the headquarters for the Pearl Harbor attack, being the hometown of the two Japanese representatives that signed the terms of surrender at the USS Battleship Missouri, serving as the place for the final kamikaze attack against the United States, and providing much of Japan’s foot soldiers for the conflict, Oita is ripe with unchronicled, raw, and diverse accounts of the Japanese experience.

The collective stories of the 43 interviewees, who lived through the war and occupation present the varied perspectives of soldiers, sailors, and pilots, who are often at the center of war discussions and experiences, but also that of students, teachers, nurses, factory workers and more, providing a multidimensional portrayal of the period.

The book begins with the early militarization of the Oita prefecture, specifically in Saiki, the location for one of the most crucial bases for the Japanese Imperial Navy. This first chapter features the perspectives of young Saiki citizens raised during the period who still see the Pearl Harbor attack with a conflicted yet enduring pride, setting the stage for following interesting discussions on Japanese post-war sentiment.

Another important aspect addressed by the Porters in this work is the mass censorship and indoctrination that took place in Japan during the war period. During this time, media censorship and military-based education helped to obscure the actual happenings of the conflict, particularly in its earlier years, as well as rallying the population in support for the Japanese navy. As well as presenting censored portrayals of the war itself, local Oita editorials both highlighted and encouraged public support for the war and the glorification of death and martyrdom. This indoctrination is also acknowledged by the Porters in relation to traditional Japanese Shinto beliefs on the emperor, specifically his divine origins. Japan's media portrayals of the conflict concerning to the state and emperor as well as its moral education curriculum feed into each other, applying moral pressure to the support of war efforts.

Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation also provides particularly interesting insights on East Asian regionalism, particularly from the perspective of Imperial Japan, which viewed itself as an “older brother leading the newly emerging members of the Asian family towards development” and promoted the idea that the Japanese were racially superior to other Asian ethnic groups. The first-hand accounts of many of the atrocities committed by Japanese in cities such as Nanjing and Shanghai as well as their glorification by the Japanese press add to the book’s depth and relevance.

As the war approached an end, conflict reached Oita. The targeting of civilians and the bombing of factories during American air raids lowered Oita morale. Continued air raids on Oita City, the prefecture’s capital city, rapidly fueled the region’s fear and resentment towards American soldiers.

In conclusion, Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation manages to present important first-hand accounts of Japanese life during one of the most consequential moments in modern history. The impact of these events on current Japan is particularly interesting when it comes to Japanese culture, especially when it comes to the glorification of war in Japanese education as well as the rising tide of Japanese nationalism.

![Farewell of Espérance Nyirasafari (left) as minister of Gender and Family Promotion, in Rwanda's capital in 2018 [Rwanda's Gov.] Farewell of Espérance Nyirasafari (left) as minister of Gender and Family Promotion, in Rwanda's capital in 2018 [Rwanda's Gov.]](/documents/10174/16849987/rwanda-blog.jpg)

▲ Farewell of Espérance Nyirasafari (left) as minister of Gender and Family Promotion, in Rwanda's capital in 2018 [Rwanda's Gov.]

March 9, 2020

ESSAY / María Rodríguez Reyero

South Africa is ranked 17th in the World Economic Forum's 2020 Global Gender Gap Index[1] (a two place increase from 2019), while Rwanda is ranked 9th (a three place decline from the previous year). Interestingly, Spain is ranked 8th (a major gain of 11 places in one year). Since 2018, Spain has made a gain of 21 places, which is only rivaled by countries like Madagascar (22), Mexico and Georgia (25) and Ethiopia (35).

Regarding political participation and governance in the last decade, the number of African women in ministerial posts has tripled. African women already account for 22.5% of parliamentary seats, a similar percentage to that of Europe (23.5%) and higher than that of the US (18%). However, does the increase in female participation in high political positions lead to a real improvement in the lives of other women? Or is female participation only a façade?

This study’s main aim is to explore the impact that women’s participation in politics has on the circumstances of the rest of women in their countries. The study is based on secondary research and quantitative data collection and will objectively analyze the situation in Spain, Rwanda, and South Africa and draw pertinent conclusions.

Rwanda

From April to July 1994, between 800,000 and one million ethnic Tutsis were brutally killed during a 100 day killing spree perpetrated by Hutus [2]. After the genocide, Rwanda was on the edge of total collapse. Entire villages had been destroyed, and social cohesion was in tatters. Yet, this small African country has made a remarkable economic turnaround since the genocide. The country now boasts intra-regional trade and has positioned itself as an attractive destination for foreign investment, being a leading country in the African economy. Rwanda’s economy appears to be thriving, with annual GDP growth averaging 7.76% between 2000 and 2019, and “growth expected to continue at a similar pace over the next few years” according to a recent study of World Finance.[3] About 70% of the survivors of the fratricidal struggle between Hutus and Tutsis are women, and thus women play a role of utmost importance in the recovery of Rwanda.[4]

The Rwandan genocide ended with the deaths of one million people and the rape of more than 200,000 women.[5] Women were the clear losers of the conflict, yet the conflict also enabled women to become the main economic, political and social engine of Rwanda during its recovery from the war. Roles traditionally assigned to men were assigned to women, which turned women into more active members of society and empowered them to fight for their rights. The main area where this shift has been felt is in politics, where gender parity reaches its highest level thanks to Rwanda’s continued commitment to equal representation. This support has led the proportion of women in the Rwandan National Parliament to even exceed that of men in the lower house, which consists of 49 women out of a total of 89 representatives.[6]

The body responsible for coordinating female protection and empowerment is the Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion, promoter of the National Gender Policy. The minister of Gender until 2018 was Espérance Nyirasafari. Nyirasafari was responsible for several main changes in Rwandan society including the approval of laws against gender-based violence. She now serves as one of two Vice Presidents of the senate of Rwanda.

Consequently, Rwanda illustrates African female advancement. In addition to currently being the world's leading country in female representation in Parliament, (in which women hold nearly 60% of the seats), Rwanda reached the fourth highest position in the las World Economic Forum's gender gap report. The only countries that came close in this respect were Namibia and South Africa.

The political representation of women in Rwanda has led to astonishing results in other areas, notably education. Rwanda’s education system is considered one of the most advanced in Africa, with free and compulsory access to primary school and the first years of high school. About 100% of Rwandan children are incorporated into primary school and 75% of young people ages 15+ are literate. However, high school attendance is significantly low, counting with just 23% of young people, of which women represent only 30%.[7] Low high school attendance is mainly due to the predominance of rural areas in the country, where education is more difficult to access, especially for women, who are frequently committed to marriage and the duties of housework and family life from a very young age. Despite the growing data and measures established, education is in reality very hard to achieve for women, who are mostly stuck at home or committed to other labor.[8]

Regarding the legislative measures put in place to achieve gender equality and better conditions and opportunities for women, Rwanda does not score high. Despite being one of the most advanced countries in gender equality, currently, no laws exist to ensure equal pay or non-discrimination in the hiring of women, according to WEF’s 2019 report, even if some relevant legal measures have been effectively been put into practice since the ratification of the 2003 Constitution, which demonstrates the progress on gender equality in Rwanda.

The Constitution also argues that the principle of gender equality must prevail in politics and that the list of members of the Chamber of Deputies must be governed by this equitable principle. The law on gender violence passed in 2008 is proof of national commitment to women's rights, as it recognizes innovative protections such as the prohibition of spousal rape, three months of compulsory maternity leave (even some Western countries such as the United States lack this protection) or equal rights in inheritance process regardless of gender.[9]

Finally the labor law passed in 2009 establishes numerous protections for Rwandan women, such as receiving the same salary as their male colleagues or the total prohibition of any gesture of sexual content towards them.

Some of the most relevant progress made in Rwanda are the reduction of the percentage of women in extreme poverty from 40% in 2001 to 16.3% in 2014, and the possession of land by 26% of women personally and 54% in a shared way with their husbands.[10] Thanks to the work and commitment of female politicians, Rwandan women today enjoy inalienable rights which women in many other countries can only dream of.[11] This ongoing egalitarian work has paid off: Rwanda is as mentioned above the 9th country in the world with a smaller gender gap, only behind Iceland, Nicaragua, Finland, Sweden, and Norway. In the annual study of the World Economic Forum, only five countries (including Rwanda, the only African) have surpassed the 50% barrier in terms of reducing the gender gap in politics. Likewise, the gender parity in economic participation that Rwanda has achieved is of great relevance, which has made it the first country in the world to include women in the world of work and equal economic remuneration. Rwanda is a regional role model in terms of egalitarian legislation.[12]

South Africa

According to IMF and World Bank latest data, South Africa currently is the second most prosperous country of the whole continent, only surpassed by Nigeria. The structure of its economy is that of a developed country, with the preeminence of the services sector, and the country stands out for its extensive natural resources, thus being considered one of the largest emerging economies nowadays. South Africa also has a seat in the BRICS economy block (with Brazil, Russia, India, and China) and is a member of the G20.

Despite its economic position, the country is also home to great inequality, largely bequeathed in its history of racial segregation. According to the New York Times, the post-apartheid society had to face great challenges: it had to “re-engineer an economy dominated by mining and expand into modern pursuits like tourism and agriculture while overcoming a legacy of colonial exploitation, racial oppression, and global isolation — the results of decades of international sanctions."[13] However, what is the role of women in this deep transformation? Has their situation improved or are they the new discriminated ones?

South Africa continues to lead the way in women's political participation in the region with 46% of women in the House of Assembly and provincial legislatures and 50% of women in the cabinet after the May 2019 elections. All the speakers in the national and provincial legislatures are women. Women parliamentarians rose from 40% in 2014 to 46% in 2019.

Rwanda, Namibia and South Africa are ranked in the top 20 countries in reducing the gender gap. On the other hand, South Africa does have established legislation about equality in salaries, but not in non-discrimination in the hiring process according to the data collected by the World Economic Forum in January 2020.

South Africa is writing a new page in its history thanks to the entry of Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma (she was elected in 2012 president of the African Union Commission becoming the first woman to lead this organization, and currently serves as Minister of Planning, Monitoring, and Evaluation in South Africa’s Government) and other women, such as Lindiwe Nonceba Sisulu (minister of International Relations and Cooperation until 2019) into the political competition.

Subsequently, women have always been involved in political organizations, as well as in the trade union movement and other civil society organizations. Although evolving in a patriarchal straitjacket due to the social role women had assigned, they don't waited for "the authorization of men" to claim their rights. This feminine tradition of political engagement in South Africa has resulted the writing of a protective Constitution for women in a post-apartheid multiracial and supposedly non-sexist context.

However, this has not led to an effective improvement in the real situation of women in the country. According to local media data,[14] a woman dies every eight hours in South Africa because of gender violence and, according to 2016 government statistics, one in five claims to have suffered at some time in her life. Besides, in South Africa, about 40,000 violations are reported annually, according to police data, the vast majority reported by women. These figures lead South Africa's statistics agency to estimate that 1.4 out of every thousand women have been raped, which places the country with one of the highest rates of this type in the world.[15]

Spain

After a cruel civil war, followed by 36 years of dictatorship, Spanish society was looking forward to a change, and thus the democratic transition took place, transforming an oppressed country into the Spain we nowadays know. In many occasions, history tends to forget the 27 women, deputies and senators of the 1977 democratic legislature who were architects of this political change (divorce law, legalize the sale of contraceptives, participate in the drafting of the Constitution of 1978, amongst others). These women also having an active role in politics, something unusual and risky for a woman at that time (without rights as basic as owning property or opening a bank account during the dictatorship). It is clear that women played a crucial role in the transformation of Spanish society, but has it really been effective?

Spain’s new data since the establishment of a new government in January 2020 is among the top 4 European countries with the highest female proportion: behind Sweden (with 47.4%), France (47.2%) and Finland (45.8%), according to the latest data published by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE).[16] After the last elections in November, Spain is placed in tenth place in the global ranking. Ahead, there are Rwanda (with 61.3%), Cuba (53.2%), Bolivia (53.1%), Mexico (48.2%) and others such as Grenada, Namibia, Sweden, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, according to data published by the World Bank. Of the 350 congress deputies, 196 are men and 154 are women, meaning that 56% of the members of the House of Representatives are men while 44% are women.

In Spain, also almost every child gets a primary education according to OECD but almost 35% of Spanish young people do not get a higher education. Of those who do go to university nearly 60% of all the students are women. They also get better grades and take on average less time to graduate than men but are less likely to hold a power position: according to PwC Spain last data, only a 19% of all directive positions are held by women, 11% of management advice are women and less than a 5% are women in direction or presidency of Spanish enterprises. This is since at least 2.5 million women in Spain cannot access the labor market because they have to take care of family care. Among men, the figure is reduced to 181,000. The data has been given by the International Labor Organization (ILO). The study also revealed that women in Spain perform 68% of all unpaid care work, dedicating twice as much time as men. About 25% of inactive women in Spain claim that they cannot work away from home because of their family charges. This percentage is much higher than those of other surrounding countries, such as Portugal (13%) or France (10%) and the European average. It is also much larger than that of Spanish men who do not work for the same reason (3%).

Regarding gender-based violence, even if Spain has since 2004 an existing regulation to severely punish it, in the year 2019 a total of 55 women have been killed by their partners or ex-partners, the highest death toll since 2015, with a total of 1,033 since they began to be credited in 2003, according to the balance of the Government Delegation for Gender Violence last data.

Conclusion

To sum up, even if African countries such as Rwanda and South Africa have more women representation and are doing well by-passing laws and measures, due to cultural reasons such as a more ingrained patriarchal society, community interventions, family pressure or the stigma of single mothers, gender equality is more difficult in Africa. Culture, in reality, makes it more difficult to be effective, whereas in Spain the measures implemented, even if they are apparently less numerous, are more effective when it comes to creating institutions that protect women. Women in Africa usually depend a lot on their husbands; they very often suffer in silence not to be left alone without financial support, a situation that in Spain has been tacked without problems.

It is not so much a legislative issue but a cultural one: in Spain, if a woman suffers gender violence and reports it, it is more likely that she would be offered government's help (monetary help, job opportunities...) in order to start a new life, and she most certainly will not be judged by society due to her circumstances. Whereas in South Africa for example, a UN Women rapporteur estimated that only one in nine rapes were reported to the police and that this number was even lower if the woman was raped by a partner, this mainly being due to the social stigma still present nowadays. In Rwanda, a 2011 report from the Rwandan Men's Resource Centre said 57% of women questioned had experienced violence from a partner, while 32% of women had been raped by their husbands, this crime being admitted by only 4% of men, as rape in marriage is seen as a normal situation due to cultural reasons: women still depend somehow on their husbands, and family is the center of society, so it must not be broken.

In numerous occasions, in African countries justice is taken at a different level, in order not to disturb the social and familial order; frequently, rape or gender violence is tackled amongst the parties by negotiating or by less traditional justice systems such as community systems like Gacaca court in Rwanda (a social form of justice designed to promote communal healing, massively used after Rwandan genocide),[17] something unbelievable in Spain, where according to official data from Equality Ministry, last year more than 40.000 reports for gender violence were heard by courts.[18]

In regard to inequality and according to the latest IMF studies, closing the gender gap in employment could increase the GDP of a country by 35% on average, of which between 7 and 8 percentage points correspond to increases in productivity thanks to gender diversity. Having one more woman in senior management or on the board of directors of a company raises the return on assets between 8 and 13 basis points. Consequently, we could state that, as shown by the data (not only those provided by the IMF, but the evident improvements that have taken place throughout this decade in Spain, Burundi, Rwanda, and South Africa) the presence of women both in top management positions and above all, in politics and governance does lead to a real improvement in the rights and lifestyles of the rest of the women, and a substantial improvement of the country as a whole.

However, after their arduous and tricky climb to the top, women inherit a political system which is difficult, if not almost impossible, to change in a few years. Furthermore, the question of the application of laws, when they exist, by the judicial system is a huge challenge in all states as well as making effective all the measures for the reduction of gender inequality. This supposes such a great challenge, not only for these women but also for the whole society, as having arrived where we are.

[1] World Economic Forum (December 2020), The Global Gender Gap Report 2020. World Economic Forum. Accessed 14/02/2020

[2] Max Roser and Mohamed Nagdy (2020), "Genocides". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Accessed 14/02/202

[3] Natalie Keffler (2019)., ‘Economic growth in Rwanda has arguably come at the cost of democratic freedom’, World Finance. Accessed 14/02/2020

[4] Charlotte Florance (2016), 22 Years After the Rwandan Genocide. Huffpost. Accessed 14/02/2020

[5] Violet K. Dixon (2009), A Study in Violence: Examining Rape in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. Inquires journal. Accessed 14/02/2020

[6] Inter-parliamentary Union (2019), ‘Women in national Parliaments’. IUP. Accessed 14/02/2020

[7] World Bank (2019), The World Bank in Rwanda. World Bank. Accessed 14/02/2020

[8] Natalie Keffler (2019)., ‘Economic growth in Rwanda has arguably come at the cost of democratic freedom’, World Finance. Accessed 14/02/2020

[9] Tony Blair. (2014), ‘20 years after the genocide, Rwanda is a beacon of hope.’ The Guardian. Accessed 14/02/20

[10] Antonio Cascais (2019), ‘Rwanda – real equality or gender-washing?’ DW. Accessed 14/02/2020

[11] Álex Maroño (2018), ‘Ruanda, ¿una utopía feminista?.’ El Orden Mundial. Accessed 14/02/2020

[12] Alexandra Topping (2014), ‘The genocide Conflict and arms Rwanda's women make strides towards equality 20 years after the genocide.’ The Guardian. Accessed 14/02/2020

[13] Peter S. Goodman (2017), ‘End of Apartheid in South Africa? Not in Economic Terms.’ The New York Times Sitio. Accessed 14/02/2020

[14] Gopolang Makou (2018), ‘Femicide in South Africa: 3 numbers about the murdering of women investigated.’ Africa Check. Accessed 14/02/2020

[15] British Broadcasting Corporation (2019), ‘Sexual violence in South Africa: 'I was raped, now I fear for my daughters'. BBC News. Accessed 14/02/2020

[16] European Institute for Gender Equality (2019). ‘Gender Equality Index.’ EIGE. Accessed 14/02/2020

[17] Gerd Hankel. (2019), ‘Gacaca Courts’, Oxford Public International Law. Accessed 14/02/2020

[18] Instituto de la mujer (2016), ‘Estadísticas violencia de género.’ Ministerio de Igualdad de España. Accessed 14/02/2020

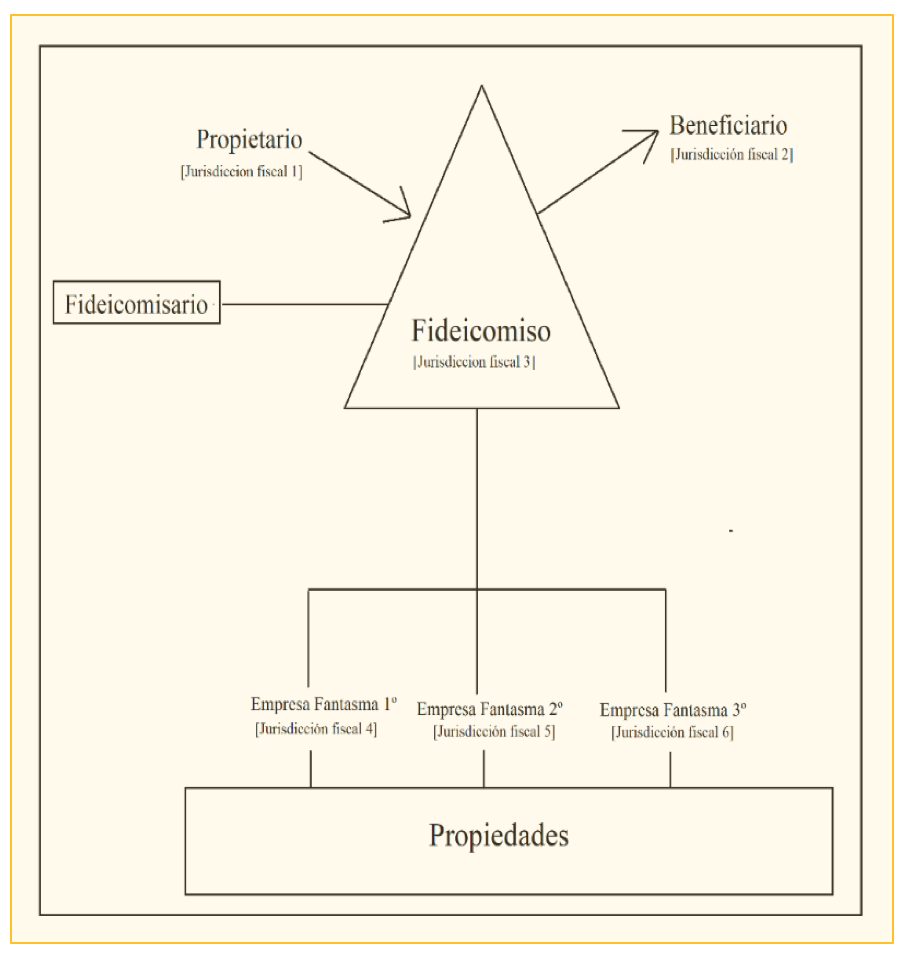

El 27% de la riqueza privada total latinoamericana está depositada en territorios que ofrecen un tratamiento impositivo favorable

Latinoamérica es la región mundial con mayor porcentaje de riqueza privada “offshore”. La cercanía de paraísos fiscales, en diversos países o dependencias insulares del Caribe, puede facilitar la llegada de esos capitales, algunos generados de forma ilícita (narcotráfico, corrupción) y todos evadidos de unas instituciones fiscales nacionales con poca fuerza supervisora y coercitiva. Latinoamérica dejó de ingresar impuestos en 2017 por valor de 335.000 millones de dólares, lo que representó el 6,3% de su PIB.

![Playa del Caribe [Pixabay] Playa del Caribe [Pixabay]](/documents/10174/16849987/paraiso-fiscal-blog.jpg)

▲ Playa del Caribe [Pixabay]

ARTÍCULO / Jokin de Carlos Sola