Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Carrera entre las fuerzas armadas de las principales potencias para desarrollar e incorporar sistemas láser

Con el desarrollo de las armas láser el uso de misiles intercontinentales podrían dejar de tener sentido, ya que son estos pueden ser fácilmente interceptados y derribados, sin provocar daños colaterales. De esta manera, la amenaza nuclear deberá girar hacia otras posibilidades, y las armas láser muy probablemente se conviertan en el nuevo objeto de deseo de las fuerzas armadas.

![Láser táctico de alta energía [US Army] Láser táctico de alta energía [US Army]](/documents/10174/16849987/laser-blog.jpg)

▲ Láser táctico de alta energía [US Army]

22 de marzo, 2019

ARTÍCULO / Isabella León

Desde que, antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el Gobierno británico ofreció más de 76.000 dólares a quien fuera capaz de diseñar un arma de rayos que pudiera matar a una oveja a 100 metros, mucho ha avanzado la tecnología en este campo. En 1960 Theodore Maiman inventó el primer láser y eso aceleró la investigación para desarrollar rayos mortales capaces de destruir cualquier artefacto enviado por el enemigo y a la vez generar importantes daños en componentes eléctricos a través de un efecto secundario de radiación. Hoy se valoran los progresos en este materia como el mayor avance militar desde la bomba atómica.

Las armas láser se valoran debido a su velocidad, agilidad, precisión, rentabilidad y propiedades antibloqueo. Estas armas son, literalmente, un haz de luz que se mueve de manera coherente, por lo que pueden golpear objetivos a una velocidad de 300.000 kilómetros por segundo, interceptar numerosos objetivos o el mismo objetivo muchas veces, llegar al objetivo con extrema precisión sin ocasionar daños colaterales y resistir a las interferencias electromagnéticas. También son mucho más baratas que las municiones convencionales, al costo de un dólar con cada disparo láser.

Sin embargo, las armas láser poseen algunas limitaciones: requieren una gran cantidad de potencia, un tamaño y peso adaptado a las plataformas militares y un manejo térmico efectivo. Además, su estructura depende de la composición de sus objetivos (las longitudes de onda se absorben o reflejan según las características de la superficie del material), de los diferentes rangos que deben alcanzar y de los distintos ambientes y efectos atmosféricos a las que serán sometidas. Estos aspectos afectan el comportamiento del arma.

No obstante, a pesar de estas limitaciones, las principales potencias han apostaron desde hace tiempo por el inmenso potencial de esta tecnología como un arma estratégica.

Estados Unidos

El Departamento de Defensa de Estados Unidos ha trabajado extensamente para contribuir al desarrollo del sistema de armas láser en campos de protección específicos, como la Marina de los Estados Unidos, el Ejército y la Fuerza Aérea.

En el departamento de defensa naval, está particularmente implicado en este campo. La Marina ha desarrollado lo que se conoce como el Sistema de Armas Láser (LaWS, por sus siglas en inglés) que consta de un láser de estado sólido y fibra óptica que actúa como arma adjunta, y está vinculado a un sistema antimisiles de fuego rápido, como un arma defensiva y ofensiva para aeronaves. El LaWS tiene como objetivo derribar pequeños drones y dañar pequeños barcos a una milla de distancia aproximadamente.

Los desarrollos más recientes han sido otorgados a la compañía multinacional Lockheed Martin, con un contrato de 150 millones de dólares, para el avance de dos sistemas de armas láser de alta potencia, conocido como HELIOS, que será el sucesor de LaWS. Este es el primer sistema en mezclar un láser de alta energía con capacidades de inteligencia, vigilancia y reconocimiento de largo alcance, y su objetivo es destruir y cegar a drones y pequeñas embarcaciones.

El Ejército también está experimentando con sistemas de armas láser para su instalación en vehículos blindados y helicópteros. En 2017, el Mando Estratégico de las Fuerzas Armadas (ARSTRAT) armó un Stryker con un láser de alta energía y desarrolló el Boeing HEL MD, su primer láser móvil de alta energía, con una plataforma contra misiles, artillería y mortero (C-RAM), que consta de un láser de estado sólido de 10kW. Simultáneamente, se han realizado investigaciones para llegar a los 50 kW y 100 kW de energía.

Por otro lado, la Fuerza Aérea desea conectar láseres a aviones de combate, aviones no tripulados y aviones de carga para atacar objetivos terrestres y aéreos. De hecho, el Ejército ha continuado con sus investigaciones para probar sus primeras armas láser aerotransportadas en el 2021. Uno de sus programas es un Gamma de 227 kg que arroja 13.3kW y cuya su estructura permite que muchos módulos láser se combinen y produzcan una luz de 100kW.

Asimismo, se ha le ha otorgado otro contrato a Lockheed Martin para que la empresa trabaje en una nueva torreta láser para aviones, en la que se implemente un haz que controle 360 grados para derribar los aviones enemigos y misiles que se encuentren arriba, debajo y detrás del avión. El sistema ha sido sometido a muchos exámenes y surgió en el proyecto SHiELD, cuyo objetivo es generar un arma láser de alta potencia para aviones tácticos de combate para 2021.

China

En los últimos años China ha implementado políticas de apertura que han puesto a la nación en contacto con el resto del mundo. El mismo proceso ha sido acompañado por una modernización de su equipo militar que se ha convertido en fuente de preocupación para sus rivales estratégicos. De hecho, han existido diversas confrontaciones diplomáticas al respecto. Con dicha modernización, China ha desarrollado un sistema de láser químico de cinco toneladas que se ubicará en la baja órbita terrestre para 2023.

China divide su sistema de armas láser en dos grupos: estratégicas y tácticas. Las primeras son de alta potencia, aéreas o terrestres que tienen como objetivo interceptar ICBM y los satélites a miles de kilómetros de distancia. Las segundas son de bajo poder, generalmente utilizadas para defensa aérea de corto alcance o defensa personal. Estos objetivos son vehículos aéreos no tripulados, misiles y aeronaves de vuelo lento y con rangos de efectividad entre pocos metros y 12 kilómetros de distancia.

Entre las innovaciones chinas más llamativas, se encuentra el Silent Hunter, un arma láser de 30 a 100kW basada en vehículos de 4 kilómetros de alcance, capaz de cortar acero de 5 mm de grosor a una distancia de un kilómetro. Este sistema fue utilizado por primera vez en la Cumbre del G20 de Hangzhou como medio de protección.

También destacan innovaciones como las armas láser individuales, que son pistolas láser que ciegan a los combatientes enemigos o sus dispositivos electro-ópticos. Dentro de esta categoría se encuentran los rifles láser deslumbrantes BBQ-905 y WJG-2002, y el arma láser cegadora PY132A y PY131A.

Otros países

Poco es conocido acerca del nivel que poseen las capacidades relacionas a la tecnología láser de Rusia. No obstante, en diciembre del año pasado, un representante del Ministerio de Defensa ruso, Krasnaya Zvezda, se refirió al sistema láser Peresvet, que forma parte del programa de modernización militar en curso del país. Los objetivos son muy claros, derribar misiles hostiles y aviones, y cegar el sistema del enemigo.

Es presumible que Rusia posee un extenso campo de investigación en esta materia, pues su política y comportamiento relacionado con las armas ha sido de constante competencia y rivalidad con Estados Unidos.

La apuesta de Alemania en relación a la tecnología láser es el demostrador de armas láser Rheinmetall, que consta con 50kW de energía y es sucesor de la última versión de 10 kW. Este sistema fue diseñado para operaciones de defensa aérea, guerra asimétrica y C-RAM. El láser Rheinmetall está compuesto por dos módulos láser montados en torretas de defensa aérea Oerlikon Revolver Gun. Este logró llegar a un destructivo láser de 50kW con la combinación de la tecnología de superposición del haz de Rheinmetall para enfocar un láser de 30kW y un láser de 20 kW en el mismo lugar.

El futuro de las armas láser

Cuando se habla de las armas láser, lo primero que se debe tener en cuenta es el tremendo impacto que tendrá esta tecnología en términos militares, que la hará determinante en el campo de batalla. De hecho, muchos otros países que cuentan con un ejército en constante modernización, han implementado este sistema: es el caso de Francia en las aeronaves Rafale F3-R; el Reino Unido con el láser de alta energía Dragonfire, o incluso Israel, que ante la creciente amenaza de misiles ha acelerado el desarrollo de esta tecnología.

Hoy en día muchos barcos, aviones y vehículos terrestres se están diseñando y ensamblando de manera tal que puedan acoger la instalación de armas láser. Se están realizando mejoras continuas para crear mayores rangos de alcance, aumentar la energía, y realizar haces de adaptación. Puede afirmarse, así, que el momento de las armas láser finalmente ha llegado.

Con el desarrollo de esta tecnología, equipos militares como los misiles ICBM o los VANT (aparatos no tripulados), principalmente, podrían dejar de tener sentido, ya que las armas láser son capaces de interceptar y derribar esos misiles, sin provocar daños colaterales. Al final, lanzar el ICBM sería una pérdida de energía, munición y dinero. De esta manera, la amenaza nuclear deberá girar hacia otras posibilidades, y las armas láser muy probablemente sean el nuevo énfasis de las fuerzas armadas.

Adicionalmente, es importante resaltar el hecho de que esta innovación militar conduce la seguridad internacional hacia la defensa, más que hacia acciones ofensivas. Por esta razón, las armas láser no anularían las tenciones de la esfera internacional, pero sí podrían llegar a disminuir de alguna manera las posibilidades de un enfrentamiento militar.

El encuentro COP24 avanzó en reglamentar el Acuerdo de París, pero siguieron bloqueados los “mercados de carbono”

Las movilizaciones en favor de que los gobiernos tomen medidas más drásticas frente al cambio climático pueden hacer olvidar que muchos países están dando pasos ciertos en la reducción de gases con efecto invernadero. Aunque normalmente las cumbres internacionales se quedan cortas respecto a las expectativas, los acuerdos climáticos van progresivamente abriéndose paso. He aquí los resultados de la última de esas cumbres: un paso pequeño, cierto, pero un paso hacia delante.

![Sesión plenaria de la COP24, celebrada en diciembre en Katowice (Polonia) [COP24] Sesión plenaria de la COP24, celebrada en diciembre en Katowice (Polonia) [COP24]](/documents/10174/16849987/cumbre-clima-blog.jpg)

▲ Sesión plenaria de la COP24, celebrada en diciembre en Katowice (Polonia) [COP24]

20 de marzo, 2019

ARTÍCULO / Sandra Redondo

La cumbre climática (también conocida como COP: Conference of the Parties) es una conferencia global preparada por la Organización de Naciones Unidas, donde se negocian medidas y acciones relacionadas con la política climática. La última, bautizada como COP24, tuvo lugar del 2 al 14 de diciembre de 2018, en la ciudad polaca de Katowice. En ella participaron cerca de 3.000 delegados de 197 países que son parte de la Convención Marco de Naciones Unidas sobre el Cambio Climático. Entre ellos se encontraban políticos, representantes de organizaciones no gubernamentales, miembros de la comunidad científica y del sector empresarial.

La primera COP tuvo lugar en 1995, y desde entonces estas cumbres han llevado a la creación del Protocolo de Kioto (COP3, 1997) y al Acuerdo de Paris (COP21, 2015), entre otros mecanismos de actuación internacional. El objetivo principal de la cita en Katowice consistía en encontrar el modo de llevar a cabo el Acuerdo de París de 2015, es decir, de implementar recortes en las emisiones contaminantes para evitar un aumento del calentamiento global. La COP24 era la última cumbre antes de 2020, año en el que entrará en vigor el Acuerdo de París.

El Acuerdo de París de 2015 fue firmado por 194 países con el objetivo de evitar que las emisiones contaminantes, causantes del efecto invernadero, aumenten la temperatura del planeta por encima de los dos grados con respecto a niveles preindustriales. La comunidad internacional pide la realización de un esfuerzo, por parte de todos, para que el aumento de temperatura no sea superior a los 1.5 grados respecto a dichos niveles. En la cumbre se pretendía crear un esquema a seguir por todos los países que fuese claro, concreto y común y así hacer realidad el acuerdo.

Desafíos

Uno de los desafíos para alcanzar ese objetivo se encuentra en establecer un equilibrio que permita a todas las naciones participar en esta lucha, pero teniendo en cuenta la realidad de cada una de ellas: las distintas capacidades tecnológicas y financieras, así como las circunstancias de vulnerabilidad y contaminación histórica. Al participar países con grandes diferencias entre ellos, es comprensible la dificultad de la tarea a realizar para llegar a un consenso. Esta era una de las medidas que se pretenden implementar del Acuerdo de París, en el cual gobiernos se comprometieron a ayudar a los países en desarrollo para lograr una adaptación mayor y más permanente.

En palabras de Patricia Espinosa, secretaria ejecutiva de la ONU para el Cambio Climático, además de medidas para hacer efectivo el Acuerdo de París es importante “impulsar un cambio cultural en las formas de producir y consumir de nuestras sociedades para repensar nuestros modelos de desarrollo”.

Wang Yi, ministro de Exteriores de China, sostuvo que su país reafirma que solo el trabajo conjunto entre todos países dará una solución efectiva en esta lucha contra el cambio climático.

En estas cumbres, los acuerdos deben ser aceptados por todos los Estados participantes, lo que puede causar que las negociaciones se alarguen. Esto fue lo que sucedió en la COP24. Se había planeado el fin de las negociaciones para el viernes, pero se prolongaron hasta que se llegó al acuerdo definitivo al día siguiente. El texto final, aprobado por todos los países asistentes, resultó ser menos ambicioso de lo esperado, especialmente en referencia a los recortes de emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero.

A pesar de las declaraciones de disposición de algunos países, ciertas tensiones fueron inevitables en las negociaciones, especialmente a la hora de asumir que es necesaria más ambición en esta lucha. Por un lado, estaba el lado conservador, con países como Estados Unidos (el cual es uno de los países que más CO2 per cápita aporta al calentamiento global) o Arabia Saudí entre otros. Al otro lado se encontraban la Unión Europea y otros Estados, algunos de ellos insulares, amenazados por el incremento del nivel del mar y que irá en aumento a causa de la subida de la temperatura global.

Otra causa de demora fue una exigencia de Turquía en el último momento, para mejorar las condiciones de financiación. Con respecto a la financiación, el acuerdo final reconoce que es necesario dedicar más recursos a esta lucha, particularmente a la reducción de gases causantes del efecto invernadero.

Informe del Panel Internacional del Cambio

Además de las medidas y los recortes que se acordaron en esta cumbre, debía realizarse una declaración con las conclusiones del informe realizado por los expertos Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos sobre el Cambio Climático (IPCC por sus siglas en inglés), en la cual se advertiría que al mundo no le queda mucho tiempo para poder evitar las peores consecuencias de este cambio climático.

En este informe, que supuso una de las grandes batallas de la cumbre, se detalla lo que pasará si la temperatura global aumenta 1,5 grados centígrados por encima de los niveles preindustriales. Actualmente la temperatura se encuentra un grado por encima de los mencionados niveles. A pesar de que debería haber sido considerado de gran importancia por todos los países, al tratarse de hechos que afectan a escala mundial, hubo países como Rusia, Kuwait, Estados Unidos o Arabia Saudí, que trataron de restarle importancia y plantearon dudas sobre la veracidad de las conclusiones del informe, mientras que otros Estados defendieron la incuestionabilidad de las conclusiones. Una característica común a estos países que se opusieron es que son los grandes productores de petróleo del planeta.

El informe del Panel Internacional del Cambio Climático (IPCC), presentado en la COP24, indica que, si se sigue sin ningún cambio, entre 2030 y 2050, estas serán las consecuencias:

–Aumento del riesgo de inundaciones de un 100% (con 1,5°C) a un 170% (con 2°C).

–Si superamos ese 1,5°C más de 400 millones de personas residentes en ciudades estarán expuestas a sequías extremas a finales de siglo.

–El hielo en el Ártico disminuirá tanto que habrá un verano sin hielo al menos una vez cada 10 años.

–150 millones de fallecimientos podrían evitarse limitando esa subida 1,5°C de temperatura

–Casi 50 millones de personas podrían verse afectadas por una subida del nivel del mar en 2100 si el incremento de temperatura excede los 1,5°C.

–Los corales serían unos de los mayores perjudicados ya que debido al aumento de la acidez de los océanos se perderían todos en 2100 si se sobrepasa el aumento de 1,5°C. Llegar a 1,5°C ocasionaría la pérdida del 70% de ellos.

Según los cálculos realizados también por el IPCC, las emisiones de CO2 deberán caer un 45% de aquí a 2030 para limitar el calentamiento a 1,5 grados. Además, en 2050 se deberá alcanzar la “neutralidad de carbono”, es decir, empezar a tener emisiones negativas o lo que es lo mismo, dejar de emitir más CO2 del que se elimina de la atmósfera. Cuanto más tiempo se tarde en llevar estas medidas a cabo, menos tiempo nos quedará antes de que las consecuencias negativas nos afecten a todos, e incluso puede que lleguen a ser irreversibles. Cada año que pasa no sólo no se reducen las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero, sino que éstas aumentan. Es por eso que ahora es el momento de actuar.

Como conclusión del informe del IPCC debe quedar claro que para evitar el aumento por encima de 1,5 grados era necesario recortar en un 45% las emisiones actuales. Sin embargo, por el desacuerdo de varios Estados con este informe, y junto con el miedo al fracaso de la cumbre, se omitieron estos recortes del acuerdo final. Esta demora en la toma de medidas drásticas solo reduce el tiempo del que disponemos para salvar nuestro planeta, arriesgándonos a llegar demasiado tarde para evitar las peores consecuencias.

Resultado

En el encuentro de Katowice fue posible el consenso en torno al reglamento sobre las medidas del Acuerdo de París, lo cual ya supone un gran logro, pero el pacto se produjo a costa de dejar a un lado los mercados de carbono, es decir, el conjunto de mecanismos de comercio de carbono que permite que países que emiten más gases de efecto invernadero puedan comprar derechos de emisión a aquellos países que sí cumplen con los objetivos y emiten gases por debajo del límite establecido. Este apartado bloqueó durante horas la negociación de otros temas, pues diversos países que se benefician de la actual situación, como Brasil, se opusieron a modificaciones. Finalmente decidió posponer la negociación hasta la convocatoria de COP25 el próximo año en Chile.

El conjunto de reglas comunes para todos los países permite presentar sus avances en la lucha contra el cambio climático del mismo modo. Hemos de recordar, que el problema que se presentó tras el Acuerdo de París fue que cada país decidió presentar los datos sobre las promesas de recortes de manera diferente. Por esta razón, un acuerdo para unificar reglas y criterios de forma común es un gran avance. Estas reglas de transparencia son especialmente importantes, puesto que permitirán analizar el avance de lo propuesto en cada momento y eso hará posible un análisis de los objetivos alcanzados y la necesidad de tomar medidas adicionales. Por ejemplo, entre los datos que se exigen a todos los países en sus informes están los sectores incluidos en sus objetivos, la emisión de gases y el año de referencia respecto al que van a medir el proceso.

A pesar de que algunos se muestran decepcionados debido a que esperaban más resultados de los que se obtuvieron, hay que considerar un éxito el mero hecho de haber alcanzado un acuerdo entre todos los países asistentes.

Debemos tener en cuenta que algunos de los Estados participantes que mostraron menos interés y pusieron menos esfuerzo en las negociaciones para esta lucha, e incluso plantearon obstáculos en las negociaciones, son países muy importantes en la esfera internacional, con gran poder económico y político. Por esta razón, debemos considerar que el acuerdo alcanzado es un paso más hacia la concienciación de la lucha contra el cambio climático. Un paso pequeño pero un paso hacia delante.

![The Forbidden City, in Beijing [MaoNo] The Forbidden City, in Beijing [MaoNo]](/documents/10174/16849987/understanding-china-blog.jpg)

▲ The Forbidden City, in Beijing [MaoNo]

ESSAY / Jakub Hodek

To fully grasp the complexities and peculiarities of Chinese domestic and foreign affairs, it is indispensable to dive into the underlying philosophical ideas that shaped how China behaves and understands the world. Perhaps the most important value to the Chinese is stability. Particularly when one considers the share of unpleasant incidents they have fared.

Climatic disasters have resulted in sub-optimal harvest and could also entail the loss of important infrastructure costing thousands of lives. For instance, the unexpected 2008 Sichuan earthquake resulted in approximately 80.000 casualties. Nevertheless, the Chinese have shown resilience and have been able to continue their day-to-day with relative ease.[1] Still, nature was not the only enemy. Various nomadic tribes such as the Xiong Nu presented a constant threat to the early Han Empire, who were forced to reinvent themselves to protect their own. [2] These struggles only amplified their desire for stability.

All philosophical ideologies rooted in China highlight the benefits of stability over the evil of chaos.[3] In fact, Legalism, Daoism and Confucianism still shape current social and political norms. This is unsurprising as the Chinese interpret stability as harmony and the best mean to achieve development. This affirmation is cultivated from birth and strengthened on all societal levels.

Legalism affirms that “punishment” trumps “rights”. Thus, the interest of few must be sacrificed for the good of the many.[4] This translates to phenomenons present in modern China such as censorship of media outlets, autocratic teachers, and rigorous laws to protect “state secrets”. Daoism attests to the existence of a cosmological order that determines events.[5] Manifestations of this can be seen in fields of Chinese traditional medicine that deals with feng shui or the flows of energy. Confucianism puts stability as an antecedent of a forward momentum and regulates the relationship between the individual and society.[6] From the Confucianism stems a norm of submission to parental expectations, and the subjugation and blind faith to the Communist Party.

It follows that non-Sino readers of Chinese affairs must consider these philosophical roots when analysing current Chinese events. Seen through that lens, actions such as Xi Jinping declaring stability as an “absolute principle that needs to be dealt with using strong hands[7],” initiatives harshly targeting corrupt Party members, increased censorship on media outlets and the widespread reinforcement of nationalism should not come as a surprise. One needs power to maintain stability.

Interestingly, it seems that this level of scrutiny over the daily lives of average Chinese people has not incited negative feelings towards the Communist Party. One of the explanations behind these occurrences might be attributed to the collectivist vision of society that the Chinese individuals possess. They strongly prefer social harmony over their own individual rights. Therefore, they are willing to trade their privacy to obtain heightened security and homogeneity.

Of course, this way of living contrasts starkly with developed Western societies who increasingly value their individual rights. Nonetheless, the Chinese in no way fell their values to be inferior to the Western ones. They are prideful and portray a sense of exceptionalism when presenting their socioeconomic developments and societal order to the rest of the world. This is not to say that, on occasion, the Chinese have been known to replicate certain foreign practices in an effort to boost their geopolitical presence and economic results.

In relation to this subtle sense of superiority shared by the Chinese, it is important to analyse the political conditionality of engaging with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) through economic or diplomatic relations. Although the Chinese government representatives have stated numerous times that, when they establish ties with foreign countries, they do not wish to influence socio-political realities of their recent partner, there are numerous examples that point to the contrary. One only has to look at their One China policy which has led many Latin American countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taiwan. In a way, this is understandable as most countries zealously protect their vision of the world. As such, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) strategically establishes economic ties with countries harbouring resources they need or that are in need of infrastructure that they can provide. The One Belt One Road initiative represents the economic arm of this vision while their recent increased diplomatic activity, especially in Africa and Latin America, the political one. In short, the People’s Republic of China wants to be at the forefront of geopolitics in a multipolar world lacking clear leadership and certainty, at least in the opinion various experts.

One explanation behind this desire for being at the centre stage of international politics hides in the etymology of their own country’s name. The term “Middle Kingdom” refers to the Chinese “Zhongguó”, where the first character “zhong” means “centre” or “middle” and “guó” means “country”, “nation” or “kingdom”.[8] The first record of this term, “Zhongguó,” can be found in the Book of Documents (“Shujing”), which is one of the Five Classics of ancient Chinese literature. It is a piece which describes ancient Chinese figures and, in some measure, serves as a basis of the Chinese political philosophy, especially Confucianism. Although the Book of Documents dates back to 4th Century A.D., it wasn’t until the beginning of the 20th Century when the term “Zhongguó” became the official name of China.[9] While it is true that the Chinese are not the only country that believes they have a higher calling to lead others, China is the only nation whose name uses such a concept.

Such deep-rooted concepts as “Zhongguó”, strongly resonates within the social fabric of Chinese modern society and implies a vision of the world order where China is at the centre and leading countries both to the East and West. This vision is embodied in Xi Jinping, the designated “core” leader of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), who is decisively dictating the tempo of China’s effort to direct the country on the path of national rejuvenation. In fact, at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in October 2017, Xi Jinping’s speech was centered around the need for national rejuvenation. An objective and a date were set out: “By 2049, China’s comprehensive national power and international influence will be at the forefront.”[10] In other words, China aims to restore its status as the Middle Kingdom by the year 2049 and become a leading world power.

The full-fleshed grand strategy can be found in “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in a New Era,” a document that is now part of China’s constitution and it’s as important of a doctrine as Mao Zedong’s political theories or anything the CCP’s has previously put forth. The Chinese are approaching these objectives promptly and efficiently and, as they have proven in the past, they are capable of great achievements when resources are available. Sure enough, the world is already experiencing Xi Jinping’s policies. Recently, Beijing has opted to invest in increased international presence to exert their influence and vision. Starting with continued emphasis on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), massive modernization of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and aggressive foreign policy.

The migration and political crisis in Europe and Trump’s isolationism have given China sufficient space to jump on the international stage and set in motion a new global order, albeit without the will to dynamite the existing one. Xi Jinping managed to renew a large part of the members of CCP’s executive bodies and left the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China notably reinforced. He did everything possible to have political capital to push the economic and diplomatic reforms to drive China to the promised land.

Another issue that is given China an opportunity to steal the spotlight is climate change. Especially, after the United States pulled out from the Paris Agreement in June 2017. Last January, Xi Jinping chose the Davos World Economic Forum to show that his country is a solid and reliable partner. Leaning on an economy with clear signs of stability and growth of around 6.7%, many who had predicted its spiralling fall had to listen as the President presented himself as a champion of free trade and the fight against global warming. After expressing its full support for the agreements reached against the emissions of gases at the climate summit held in Paris in 2016, Xi announced the will of “the Middle Kingdom” to guide the new economic globalization.

President Xi plans to achieve his vision with a two-pronged approach. First, a wide-ranging promotion abroad of “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in a New Era.” This is an unknown strategy to the Chinese as there is no precedent of the CCP’s ideas being promoted abroad. However, Xi views Western liberal democracy as an impediment to China’s rise and wants to offer an alternative in the form of Chinese socialism, which he perceives as practically and theoretically superior. The Chinese model of governing provides a way to catch up with the developed nations and avoid the regression to modern age colonialism.[11] This could turn out to be an attractive proposal to developing nations who might just be lured by China’s “benevolent” governance and “generosity” in the form of low-interest loans. Second, Xi wants to further develop and modernize the PLA so that it is capable to ensure national security and maintain Chinese positions in areas where their foreign policy has become more assertive (not to say aggressive) such as in the South China Sea.[12] Confirming that both strong military and economic sustainability are essential to achieve the strategic goal of becoming the centre of their proposed global order by 2049.

If one desires to understand China today, one must look carefully at its origin. What started off as an isolated nation turned out to be a dormant giant that was only waiting to get its home affairs in order before it went for the rest of the world. If there is any lesson behind recent Chinese actions across the political and socioeconomical spectrum is that they want to live up to their name and be at the forefront of the world. This is not to say that they wish an implosion of the current world order although it is clear they are willing to use force if need be. It merely implies that they believe their philosophical ideologies to be at least as good as those shared in Western societies while not forgoing what they find useful from them: free trade, service-based economy, developed financial markets, among other things. As things stand, China is sure to make some friends along the way. Especially in developing regions that might be tempted by their tremendous economic success in the last decades and offers of help “with no strings attached.” These realities imply that we live in a multipolar which is increasingly heterogenous in connection to values and references that rule it. Therefore, understanding Chinese mentality will prove essential to understand the future of geopolitics.

[1] Daniell, James. “Sichuan 2008: A Disaster on an Immense Scale.” BBC News, BBC, 9 May 2013, www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-22398684.

[2] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Xiongnu.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 6 Sept. 2017, www.britannica.com/topic/Xiongnu.

[3] Creel, Herrlee Glessner. "Chinese thought, from Confucius to Mao Tse-tung." (1953).

[4] Hsiao, Kung-chuan. "Legalism and autocracy in traditional China." Chinese Studies in History 10.1-2 (1976)

[5] Kohn, Livia. Daoism and Chinese culture. Lulu Press, Inc, 2017

[6] Yao, Xinzhong. An introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

[7] Blanchard, Ben. “China's Xi Demands 'Strong Hands' to Maintain Stability Ahead of Congr.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 19 Sept. 2017.

[8] Diccionario conciso español-chino, chino español. Beijing, China: Shangwu Yinshuguan. 2007.

[9] Nylan, Michael (2001), The Five Confucian Classics, Yale University Press.

[10] Tuan N. Pham. “China in 2018: What to Expect.” The Diplomat, 11 Jan. 2018.

[11]Li, Xiaojun. "Does Conditionality Still Work? China’s Development Assistance and Democracy in Africa." Chinese Political Science Review 2.2 (2017): 201-220.

[12] Chase, Michael S. "PLA Rocket Force Modernization and China’s Military Reforms." (2018).

La ruptura con Rusia de los ortodoxos de Ucrania traslada al ámbito religioso la tensión entre Kiev y Moscú

Mientras Rusia cerraba a Ucrania los accesos del Mar de Azov, a finales de 2018, la Iglesia Ortodoxa Ucraniana avanzaba en su independencia respecto al Patriarcado de Moscú, cortando un importante elemento de influencia rusa sobre la sociedad ucraniana. En la “guerra híbrida” planteada por Vladimir Putin, con sus episodios de contraofensivas, la religión es un ámbito más de soterrada pugna.

![Proclamación de autocefalia de la Iglesia Ortodoxa de Ucrania, con asistencia del presidente ucraniano Poroshenko [Mykola Lazarenko] Proclamación de autocefalia de la Iglesia Ortodoxa de Ucrania, con asistencia del presidente ucraniano Poroshenko [Mykola Lazarenko]](/documents/10174/16849987/iglesia-ortodoxa-blog.jpg)

▲ Proclamación de autocefalia de la Iglesia Ortodoxa de Ucrania, con asistencia del presidente ucraniano Poroshenko [Mykola Lazarenko]

ARTÍCULO / Paula Ulibarrena

El 5 de enero de 2019 fue un día importante para la Iglesia Ortodoxa. En la histórica Constantinopla, hoy Estambul, en la catedral ortodoxa de San Jorge, se verificó la ruptura eclesiástica entre el rus de Kiev y Moscú, naciendo así la decimoquinta Iglesia Ortodoxa autocéfala, la de Ucrania.

El patriarca ecuménico de Constantinopla, Bartolomé I, presidió el acto junto al metropolitano de Kiev, Epifanio, que fue elegido en otoño pasado por parte de los obispos ucranianos que quisieron escindirse del Patriarcado de Moscú. Tras un solemne recibimiento coral a Epifanio, de 39 años, los dirigentes eclesiásticos colocaron en una mesa del templo el tomos (decreto), un pergamino escrito en griego que certifica la independencia de la Iglesia de Ucrania.

Pero quien realmente encabezó la delegación ucraniana fue el presidente de esa república, Petró Poroshenko. “Es un acontecimiento histórico y un gran día porque hemos podido escuchar una oración en ucraniano en la catedral de San Jorge”, escribió momentos después Poroshenko en su cuenta de la red social Twitter.

El acto contó con el frontal rechazo del Patriarcado de Moscú, que lleva tiempo enfrentado con el patriarca ecuménico de Constantinopla. El arzobispo Ilarión, jefe de relaciones exteriores de la Iglesia Ortodoxa Rusa, comparó la situación con el Cisma de Oriente y Occidente de 1054 y advirtió de que el conflicto actual puede prolongarse "por decenios e incluso siglos".

El gran cisma

Así se denomina al cisma o separación de la Iglesia de Oriente (Ortodoxa) de la Iglesia Católica de Roma. La separación se gestó a lo largo de siglos de desavenencias comenzando por el momento en que el emperador Teodosio el Grande dividió a su muerte (año 395) el Imperio Romano en dos partes entre sus hijos: Honorio y Arcadio. Sin embargo, no se llegó a la ruptura efectiva hasta 1054. Las causas son de tipo étnico por diferencias entre latinos y orientales, políticos por el apoyo de Roma a Carlomagno y de la Iglesia oriental a los emperadores de Constantinopla pero sobre todo por las diferencias religiosas que a lo largo de esos años fueron distanciando a ambas iglesias, tanto en aspectos como santorales, diferencias de culto, y sobre todo por la pretensión de ambas sedes eclesiásticas de ser la cabeza de la Cristiandad.

Cuando Constantino el Grande mudó la capital del imperio de Roma a Constantinopla, esta pasó a ser denominada la Nueva Roma. Tras la caída del imperio romano de Oriente a manos de los turcos en 1453 Moscú utilizó la denominación de “Tercera Roma”. Las raíces de este sentimiento comenzaron a gestarse durante el reinado del gran duque de Moscú Iván III, que había contraído matrimonio con Sofía Paleóloga quien era sobrina del último soberano de Bizancio, de manera que Iván podía reclamar ser el heredero del derrumbado Imperio Bizantino.

Las diferentes iglesias ortodoxas

La Iglesia Ortodoxa no tiene una unidad jerárquica, sino que está constituida por 15 iglesias autocéfalas que reconocen solo el poder de su propia autoridad jerárquica, pero mantienen entre sí comunión doctrinal y sacramental. Dicha autoridad jerárquica se equipara habitualmente a la delimitación geográfica del poder político, de modo que las diferentes iglesias ortodoxas han ido estructurándose en torno a los Estados o países que se han configurado a lo largo de la historia, en el área que surgió del Imperio Romano de Oriente, y posteriormente ocupó el Imperio Otomano.

Son las siguientes iglesias: la de Constantinopla, la rusa (que es la mayor, con 140 millones de fieles), la serbia, la rumana, la búlgara, la chipriota, de georgiana, la polaca, la checa y eslovaca, la albanesa y la ortodoxa de América, así como las muy prestigiosas pero pequeñas de Alejandría, Jerusalén y Antioquía (para Siria).

La Iglesia Ortodoxa de Ucrania ha dependido históricamente de la rusa, paralelamente a la dependencia del país respecto a Rusia. En 1991 a raíz de la caída del comunismo y de la desaparición de la URSS, muchos obispos ucranianos autoproclamaron el Patriarcado de Kiev y se separan de la Iglesia Ortodoxa Rusa. Esta separación fue cismática y no obtuvo apoyo del resto de iglesias y patriarcados ortodoxos, y de hecho supuso que en Ucrania coexistiesen dos iglesias ortodoxas: el Patriarcado de Kiev y la Iglesia Ucraniana dependiente del Patriarcado de Moscú.

Sin embargo esta falta de apoyos iniciales cambió el año pasado. El 2 de julio de 2018, Bartolomé, patriarca de Constantinopla, declaró que no existe ningún territorio canónico de la Iglesia Ortodoxa Rusa en Ucrania ya que Moscú se anexionó la Iglesia Ucraniana en 1686 de forma canónicamente inaceptable. El 11 de octubre, el Santo Sínodo del Patriarcado Ecuménico de Constantinopla decidió conceder la autocefalia del Patriarca Ecuménico a la Iglesia Ortodoxa de Ucrania y revocó la validez de la carta sinodal de 1686, que concedía el derecho al Patriarca de Moscú para ordenar al Metropolitano de Kiev. Esto llevó a la reunificación de la Iglesia Ortodoxa Ucraniana y su ruptura de relaciones con la de Moscú.

El 15 de diciembre, en la Catedral de Santa Sofía de Kiev, se celebró el Sínodo Extraordinario de Unificación de las tres iglesias ortodoxas ucranianas, siendo elegido como Metropolitano de Kiev y toda Ucrania el arzobispo de Pereýaslav-Jmelnitski y Bila Tserkva Yepifany (Dumenko). El 5 de enero de 2019, en la Catedral patriarcal de San Jorge en Estambul el Patriarca Ecuménico de Constantinopla Bartolomé I rubricó el tomos de autocefalia de la Iglesia Ortodoxa de Ucrania.

La política, ¿acompaña la división o es su causa?

En el Este de Europa es casi una tradición la relación íntima entre religión y política, como ha sido desde los principios de la Iglesia Ortodoxa. Parece evidente que la confrontación política entre Rusia y Ucrania es paralela al cisma entre las iglesias ortodoxas de Moscú y Kiev, e incluso es un factor más que añade tensión a este enfrentamiento. De hecho, el simbolismo político del acto de Constantinopla se vio reforzado por el hecho de que fue Poroshenko, y no Epifanio, el que recibió el tomos de manos del patriarca ecuménico, al que agradeció el “coraje de tomar esta histórica decisión”. Anteriormente el mandatario ucraniano ya había comparado este hecho con el referéndum mediante el que Ucrania se independizó de la URSS en 1991 y con la “aspiración a ingresar en la Unión Europea y la OTAN”.

Aunque la separación llevaba años gestándose, curiosamente la búsqueda de esa independencia religiosa se ha intensificado tras la anexión por parte de Rusia de la península ucraniana de Crimea en 2014 y el apoyo de Moscú a milicias separatistas en el este de Ucrania.

El primer resultado se hizo público el 3 de noviembre, con una visita de Poroshenko a Fanar, la sede de Bartolomé en Estambul, tras la cual el patriarca subrayó su apoyo a la autonomía eclesiástica de Ucrania.

El reconocimiento de Constantinopla de una iglesia autónoma ucrania supone también un impulso para Poroshenko, que se enfrenta a una dura carrera electoral en marzo. En el poder desde 2014, Poroshenko ha centrado en el asunto religioso gran parte de su discurso. “Ejército, idioma, fe”, es su principal eslogan electoral. De hecho, tras la separación, el mandatario afirmó: “nace la Iglesia Ortodoxa Ucraniana sin Putin y sin Kirill, pero con Dios y con Ucrania”.

Kiev asegura que las iglesias ortodoxas respaldadas por Moscú en Ucrania —unas 12.000 parroquias— son en realidad una herramienta de propaganda del Kremlin, que las emplea también para apoyar a los rebeldes prorrusos del Donbás. Las iglesias lo niegan rotundamente.

En el otro lado, Vladímir Putin, que se erigió hace años como defensor de Rusia como potencia ortodoxa y cuenta con el patriarca de Moscú entre sus aliados, se opone fervientemente a la separación y ha advertido de que la división producirá “una gran disputa, si no un derramamiento de sangre”.

Además, para el patriarcado de Moscú —que rivaliza desde hace años con el de Constantinopla como centro de poder ortodoxo— supone un duro golpe. La Iglesia Rusa tiene alrededor de 150 millones de cristianos ortodoxos bajo su autoridad, y con esta separación perdería una quinta parte, aunque todavía seguiría siendo el patriarcado ortodoxo más numeroso.

También este hecho tiene un gemelo político, pues Rusia ha afirmado que romperá relaciones con Constantinopla. Vladimir Putin sabe que pierde una de las mayores fuentes de influencia que posee en Ucrania (y en lo que él llama “el mundo ruso"): el de la Iglesia Ortodoxa. Para Putin, Ucrania se encuentra en el centro del nacimiento del pueblo ruso. Esta es una de las razones, junto a la importante posición geoestratégica de Ucrania y su extensión territorial, por las que Moscú quiere seguir manteniendo la soberanía espiritual sobre la antigua república soviética, ya que políticamente Ucrania se está acercando a Occidente, tanto a la UE y como a Estados Unidos.

Tampoco hay que olvidar la carga simbólica. La capital ucraniana, Kiev, fue el punto de partida y origen de la Iglesia Ortodoxa Rusa, algo que acostumbra a recordar el propio presidente Putin. Fue allí donde el príncipe Vladimir, figura eslava medieval reverenciada tanto por Rusia como por Ucrania, se convirtió al Cristianismo en el año 988. “Si la Iglesia Ucraniana gana su autocefalia, Rusia perderá el control de esa parte de la historia que reclama como origen de la suya propia”, asegura a la BBC el doctor Taras Kuzio, profesor en la Academia de Mohyla de Kiev. “Perderá también gran parte de los símbolos históricos que forman parte del nacionalismo ruso que defiende Putin, tales como el monasterio de las Cuevas de Kiev o la catedral de Santa Sofía, que pasarán a ser enteramente ucranianos. Es un golpe para los emblemas nacionalistas de los que presume Putin”.

Otro aspecto a considerar es que las iglesias ortodoxas de otros países (Serbia, Rumanía, Alejandría, Jerusalén, etc) se empiezan a alinear a un lado u otro de la gran grieta: con Moscú o con Constantinopla. No está claro si esto quedará como un cisma meramente religioso, de producirse, o si arrastrará también al poder político, pues no hay que olvidar, como ya se ha señalado, que en ese área que denominamos Oriente siempre han existido unos lazos muy fuertes entre poder religioso y político desde el gran cisma con Roma.

|

Ceremonia de entronización del erigido patriarca de la Iglesia Ortodoxa de Ucrania [Mykola Lazarenko] |

¿Por qué ahora?

El anuncio de la escisión entre ambas iglesias es, para algunos, algo lógico en términos históricos. “Tras la caída del Imperio Bizantino, las iglesias ortodoxas independientes fueron configurándose en el siglo XIX de acuerdo a las fronteras nacionales de los países y este es el patrón que, con retraso, está siguiendo ahora Ucrania”, explica en la citada información de la BBC el teólogo Aristotle Papanikolaou director del Centro de Estudios Cristianos Ortodoxos de la Universidad de Fordham, en Estados Unidos.

Hay que considerar que es la oportunidad de Constantinopla de restar poder a la Iglesia de Moscú, pero sobre todo es la reacción del sentimiento general ucraniano frente a la actitud de Rusia. “¿Cómo pueden los ucranianos aceptar como guías espirituales a miembros de una iglesia que se cree implicada en las agresiones imperialistas rusas?”, se pregunta Papanikolau, reconociendo el impacto que la guerra de Crimea y su posterior anexión pudo haber tenido en la actitud de los eclesiásticos de Constantinopla.

Existe, pues, una relación clara y paralela entre el deterioro de las relaciones políticas entre Ucrania y Rusia, y la separación entre el rus de Kiev frente a la Iglesia de Moscú. Ambas iglesias ortodoxas están muy imbricadas, no solo en sus respectivas sociedades, sino también en los ámbitos políticos y estos a su vez utilizan para sus fines la importante ascendencia de las iglesias sobre los habitantes de los dos países. En definitiva, la tensión política arrastra o favorece la tensión eclesiástica, pero a su vez las aspiraciones de independencia de la Iglesia Ucraniana ven este momento de enfrentamiento político como el idóneo para independizarse de la moscovita.

Tras cuatro años de junta militar, las próximas elecciones abren la posibilidad de retornar a una legitimidad demasiado interrumpida por golpes de Estado

Tailandia ha conocido diversos golpes de Estado e intentos de vuelta a la democracia en su historia más reciente. La Junta militar que se hizo con el poder en 2014 ha convocado elecciones para el 24 de marzo. El deseo, sin éxito, de la hermana del rey Maha Vajiralongkorn de concurrir a las elecciones para acceder al puesto de primera ministra ha llamado la atención mundial sobre un sistema político que no logra atender las aspiraciones políticas de los tailandeses.

![Escena de una calle de Bangkok [Pixabay] Escena de una calle de Bangkok [Pixabay]](/documents/10174/16849987/tailandia-elecciones-blog.jpg)

▲ Escena de una calle de Bangkok [Pixabay]

ARTÍCULO / María Martín Andrade

Tailandia es uno de los países integrantes de ASEAN que más rápido se está desarrollando en términos económicos. No obstante, estos avances se encuentran con un difícil obstáculo: la inestabilidad política que el país arrastra desde principios del siglo XX y que abre un nuevo capítulo ahora, en 2019, con las elecciones que tendrán lugar el 24 de marzo. Estas elecciones suponen un antes y un después en la política tailandesa reciente, después de que en 2014, el general Prayut Chan-Ocha diese un golpe de Estado y se convirtiera en primer ministro de Tailandia encabezando el NCPO (Consejo Nacional para la Paz y el Orden), la junta de gobierno constituida para dirigir el país.

Sin embargo, no son pocos los que se muestran escépticos ante esta nueva entrada de la democracia. Para empezar, las elecciones se fijaron inicialmente para el 24 de febrero, pero poco tiempo después el Gobierno anunció un cambio de fecha y las convocó para un mes más tarde. Algunos han expresado sospechas acerca de una estrategia para que las elecciones no tengan lugar, ya que, según la ley, no pueden celebrarse una vez transcurridos ciento cincuenta días a partir de la publicación de las diez últimas leyes orgánicas. Otros temen que el NCPO se haya dado más tiempo para comprar votos, al tiempo que comentan su inquietud por la posibilidad de que la Comisión Electoral, que es una administración independiente, sea manipulada para lograr un éxito que a la junta militar le va a resultar difícil asegurar.

Centrando este análisis en lo que el futuro depara a la política tailandesa, es necesario remontarse a su trayectoria en el último siglo para darse cuenta de que sigue una estela circular.

Los golpes de Estado no son algo nuevo en el país (1). Ha habido doce desde que en 1932 se firmó la primera Constitución. Todo responde a una interminable pugna entre el “ala castrense”, que ve el constitucionalismo como una importación occidental que no termina de encajar con las estructuras tailandesas (también defiende el nacionalismo y venera la imagen del rey como símbolo de la nación, la religión budista y la vida ceremonial), y la “órbita izquierdista”, originariamente compuesta por emigrantes chinos y vietnamitas, que percibe la institucionalidad del país como similar a la de la “China pre-revolucionaria” y que a lo largo de todo el siglo XX se expresó por medio de guerrillas. A esta última ideología hay que añadir el movimiento estudiantil, que desde los comienzos de la década de 1960 critica la “americanización”, la pobreza, el orden tradicional de la sociedad y el régimen militar.

Con el boom urbano iniciado en la década de 1970, el producto interior bruto se quintuplicó y el sector industrial pasó a ser el de mayor crecimiento, gracias a la producción de bienes tecnológicos y a las inversiones que las empresas japonesas empezaron a hacer en el país. Durante esta época se produjeron golpes de Estado, como el de 1976, y numerosas manifestaciones estudiantiles y acciones guerrilleras. Tras el golpe de 1991 y nuevas elecciones se abrió un debate sobre cómo crear un sistema político eficiente y una sociedad adaptada a la globalización.

Estos esfuerzos se truncaron cuando llegó la crisis económica de 1997, que generó divisiones y despertó rechazo hacia la globalización, por considerarla la fuerza maligna que había llevado el país a la miseria. Es en este punto cuando entró en escena alguien que desde entonces ha sido clave en la política tailandesa y que sin duda marcará las elecciones de marzo: Thaksin Shinawatra.

Shinawatra, un importante empresario, creó el partido Thai Rak Thai (Thai ama Thai) como reacción nacionalista a la crisis. En 2001 ganó las elecciones y apostó por el crecimiento económico y la creación de grandes empresas, pero a la vez ejerció un intenso control sobre los medios de comunicación, atacando a aquellos que se atrevían a criticarle y permitiendo únicamente la publicación de noticias positivas. En 2006 se produjo un golpe de Estado para derrocar a Shinawatra, acusado de graves delitos de corrupción. No obstante, Shinawatra volvió a ganar los comicios en 2007, esta vez con el Partido del Poder Popular.

En 2008 se produjo una nueva asonada, pero la marca Shinawatra, representada por la hermana del exprimer ministro, ganó las elecciones en 2011, esta vez con el partido Pheu Thai. Yingluck Shinawatra se convirtió así en la primera mujer en presidir el Gobierno de Tailandia. En 2014 otro golpe la apartó a ella e instauró una junta que ha gobernado hasta ahora, con un discurso basado en la lucha contra la corrupción, la protección de la monarquía, y el rechazo a las políticas electorales, consideradas como la epidemia nacional.

En este contexto, todo el esfuerzo de la junta, que se presenta en marzo bajo el nombre del partido Palang Pracharat, se ha centrado en debilitar a Pheu Thai y así eliminar del mapa todo rastro que quede de Shinawatra. Para conseguir esto, la junta ha procedido a reformar el sistema electoral (en 2016 una nueva Constitución sustituyó a la de 1997), de forma que el Senado ya no es elegido por los ciudadanos.

A pesar de todos los esfuerzos manifestados en la compra de votos, la posible manipulación de la Comisión Electoral y la reforma del sistema electoral, se intuye que la sociedad tailandesa puede hacer oír su voz de cansancio del gobierno militar, que además pierde apoyo en Bangkok y en el sur. A esto se añade el convencimiento colectivo de que, más que perseguir el crecimiento económico, la Junta se ha centrado en conseguir la estabilidad haciendo más desigual la economía de Tailandia, según datos de Credit Suisse. Por ello mismo, el resto de los partidos que se presentan a estas elecciones, Prachorath, Pheu Thai, y Bhumjaithai, coinciden en que Tailandia se tiene que volver a integrar en la competencia global y que el mercado capitalista tiene que crecer.

A principios de febrero el contexto se complicó aún más, cuando la princesa Ulboratana, la hermana del actual rey, Maha Vajiralongkorn, comunicó la presentación de su candidatura en las elecciones como representante del partido Thai Raksa Chart, aliado de Thaksin Shinawatra. Esta noticia supuso una gran anomalía, no únicamente por el hecho de que un miembro de la monarquía mostrase su intención de participar activamente en política, algo que no ocurría desde que en 1932 se pusiera fin a la monarquía absoluta, sino porque además todos los golpes de estado que se han dado en el país han contado con el respaldo de la familia real. El último, de 2014, contó con la bendición del entonces rey Bhumibol. Asimismo, la familia real siempre ha contado con el apoyo de la Junta militar.

En aras de evitar un enfrentamiento que dañaba a la monarquía, el rey reaccionó con rapidez y mostró públicamente su rechazo a la candidatura de su hermana; finalmente la Comisión Electoral decidió retirarla del proceso de elecciones.

Gobierno deficiente

Durante los últimos años la Junta militar ha sido responsable de mala gobernanza, de la débil institucionalidad del país y de una economía amenazada por las sanciones internacionales que buscan castigar la falta de democracia interna.

Para empezar, siguiendo el artículo 44 de la Constitución proclamada en 2016, el NCPO tiene legitimidad para intervenir en los poderes legislativo, judicial y ejecutivo con el pretexto de proteger a Tailandia de amenazas contra el orden público, la monarquía o la economía. Esto no solo impide toda posibilidad de interacción y resolución efectiva de conflictos con otros actores, sino que es un rasgo inequívoco de un sistema autoritario.

Han sido precisamente sus características de régimen autoritario, que es como se puede calificar a su sistema gubernamental, las que han hecho a la comunidad internacional reaccionar desde el golpe de 2014, imponiendo diversas sanciones que pueden afectar a Tailandia seriamente. Estados Unidos suspendió 4,7 millones de dólares de asistencia financiera, mientras que Europa ha puesto objeciones en la negociación de un acuerdo de libre comercio, pues como ha indicado Pirkka Tappiola, representante de la UE ante Tailandia, solo será posible establecer un acuerdo de ese tipo con un gobierno democráticamente elegido. Además, Japón, principal inversor en el país, ha empezado a buscar vías alternativas, implantando fábricas en otros lugares de la región como Myanmar o Laos.

Ante el cuestionamiento de su gestión, la Junta reaccionó dedicando 2.700 millones de dólares a programas destinados a los sectores más pobres de la población más pobres, especialmente los campesinos, e invirtiendo cerca de 30.000 millones en la construcción de infraestructuras en zonas aún no explotadas.

Dado que las exportaciones en Tailandia son el 70% de su PIB, el Gobierno no se puede permitir el lujo de tener a la comunidad internacional enfrentada. Eso explica que la Junta creara un comité para gestionar problemas referentes a los derechos humanos, denunciados desde el exterior, si bien el objetivo de la iniciativa parece haber sido más bien publicitario.

De cara a una nueva etapa democrática, la Junta tiene una estrategia. Habiendo puesto la mayor parte de sus esfuerzos en la creación de nuevas infraestructuras, espera abrir un corredor económico, el Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC), con el que convertir las tres principales provincias costeras (Chonburi, Rayong, y Chachoengsao) en zonas económicas especiales donde se potencien industrias como las del automóvil o la aviación, y que sean atractivas para la inversión extranjera una vez despejada la legitimación democrática.

Es difícil prever qué ocurrirá en Tailandia en las elecciones del 24 de marzo. Aunque casi todo habla de una nueva vuelta a la democracia, está por ver el resultado del partido creado por los militares (Pralang Pracharat) y su firmeza en el compromiso con un juego institucional realmente honesto. Si Tailandia quiere seguir creciendo económicamente y atraer de nuevo a inversores extranjeros, los militares debieran dar pronto paso a un proceso completamente civil. Posiblemente no será un camino sin contratiempos, pues la democracia es un vestido que hasta ahora le ha venido un tanto ajustado al país.

(1) Baker, C. , Phongpaichit, P. (2005). A History of Thailand. Cambridge, Univeristy Press, New York.

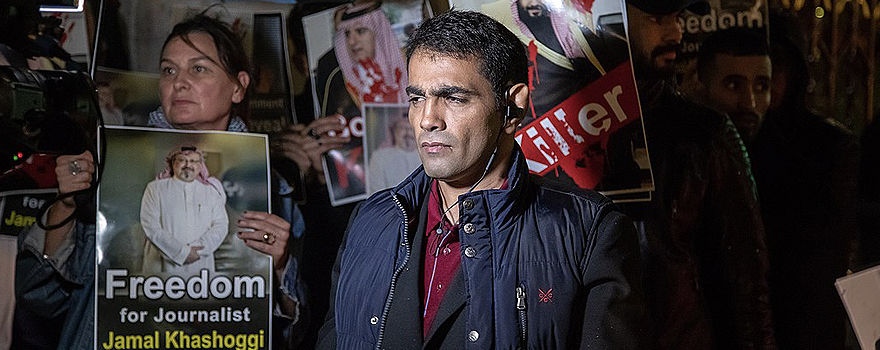

▲ Protest in London in October 2018 after the disappearance of Jamal Khashoggi [John Lubbock, Wikimedia Commons]

ANALYSIS / Naomi Moreno Cosgrove

October 2nd last year was the last time Jamal Khashoggi—a well-known journalist and critic of the Saudi government—was seen alive. The Saudi writer, United States resident and Washington Post columnist, had entered the Saudi consulate in the Turkish city of Istanbul with the aim of obtaining documentation that would certify he had divorced his previous wife, so he could remarry; but never left.

After weeks of divulging bits of information, the Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, laid out his first detailed account of the killing of the dissident journalist inside the Saudi Consulate. Eighteen days after Khashoggi disappeared, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) acknowledged that the 59-year-old writer had died after his disappearance, revealing in their investigation findings that Jamal Khashoggi died after an apparent “fist-fight” inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul; but findings were not reliable. Resultantly, the acknowledgement by the KSA of the killing in its own consulate seemed to pose more questions than answers.

Eventually, after weeks of repeated denials that it had anything to do with his disappearance, the contradictory scenes, which were the latest twists in the “fast-moving saga”, forced the kingdom to eventually acknowledge that indeed it was Saudi officials who were behind the gruesome murder thus damaging the image of the kingdom and its 33-year-old crown prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS). What had happened was that the culmination of these events, including more than a dozen Saudi officials who reportedly flew into Istanbul and entered the consulate just before Khashoggi was there, left many sceptics wondering how it was possible for MBS to not know. Hence, the world now casts doubt on the KSA’s explanation over Khashoggi’s death, especially when it comes to the shifting explanations and MBS’ role in the conspiracy.

As follows, the aim of this study is to examine the backlash Saudi Arabia’s alleged guilt has caused, in particular, regarding European state-of-affairs towards the Middle East country. To that end, I will analyse various actions taken by European countries which have engaged in the matter and the different modus operandi these have carried out in order to reject a bloodshed in which arms selling to the kingdom has become the key issue.

Since Khashoggi went missing and while Turkey promised it would expose the “naked truth” about what happened in the Saudi consulate, Western countries had been putting pressure on the KSA for it to provide facts about its ambiguous account on the journalist’s death. In a joint statement released on Sunday 21st October 2018, the United Kingdom, France and Germany said: “There remains an urgent need for clarification of exactly what happened on 2nd October – beyond the hypotheses that have been raised so far in the Saudi investigation, which need to be backed by facts to be considered credible.” What happened after the kingdom eventually revealed the truth behind the murder, was a rather different backlash. In fact, regarding post-truth reactions amongst European countries, rather divergent responses have occurred.

Terminating arms selling exports to the KSA had already been carried out by a number of countries since the kingdom launched airstrikes on Yemen in 2015; a conflict that has driven much of Yemen’s population to be victims of an atrocious famine. The truth is that arms acquisition is crucial for the KSA, one of the world’s biggest weapons importers which is heading a military coalition in order to fight a proxy war in which tens of thousands of people have died, causing a major humanitarian catastrophe. In this context, calls for more constraints have been growing particularly in Europe since the killing of the dissident journalist. These countries, which now demand transparent clarifications in contrast to the opacity in the kingdom’s already-given explanations, are threatening the KSA with suspending military supply to the kingdom.

COUNTRIES THAT HAVE CEASED ARMS SELLING

Germany

Probably one of the best examples with regards to the ceasing of arms selling—after not been pleased with Saudi state of affairs—is Germany. Following the acknowledgement of what happened to Khashoggi, German Chancellor Angela Merkel declared in a statement that she condemned his death with total sharpness, thus calling for transparency in the context of the situation, and stating that her government halted previously approved arms exports thus leaving open what would happen with those already authorised contracts, and that it wouldn’t approve any new weapons exports to the KSA: “I agree with all those who say that the, albeit already limited, arms export can’t take place in the current circumstances,” she said at a news conference.

So far this year, the KSA was the second largest customer in the German defence industry just after Algeria, as until September last year, the German federal government allocated export licenses of arms exports to the kingdom worth 416.4 million euros. Respectively, according to German Foreign Affair Minister, Heiko Maas, Germany was the fourth largest exporter of weapons to the KSA.

This is not the first time the German government has made such a vow. A clause exists in the coalition agreement signed by Germany’s governing parties earlier in 2018 which stated that no weapons exports may be approved to any country “directly” involved in the Yemeni conflict in response to the kingdom’s countless airstrikes carried out against Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in the area for several years. Yet, what is clear is that after Khashoggi’s murder, the coalition’s agreement has been exacerbated. Adding to this military sanction Germany went even further and proposed explicit sanctions to the Saudi authorities who were directly linked to the killing. As follows, by stating that “there are more questions unanswered than answered,” Maas declared that Germany has issued the ban for entering Europe’s border-free Schengen zone—in close coordination with France and Britain—against the 18 Saudi nationals who are “allegedly connected to this crime.”

Following the decision, Germany has thus become the first major US ally to challenge future arms sales in the light of Khashoggi’s case and there is thus a high likelihood that this deal suspension puts pressure on other exporters to carry out the same approach in the light of Germany’s Economy Minister, Peter Altmaier’s, call on other European Union members to take similar action, arguing that “Germany acting alone would limit the message to Riyadh.”

Norway

Following the line of the latter claim, on November 9th last year, Norway became the first country to back Germany’s decision when it announced it would freeze new licenses for arms exports to the KSA. Resultantly, in her statement, Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ine Eriksen Søreide, declared that the government had decided that in the present situation they will not give new licenses for the export of defence material or multipurpose good for military use to Saudi Arabia. According to the Søreide, this decision was taken after “a broad assessment of recent developments in Saudi Arabia and the unclear situation in Yemen.” Although Norwegian ministry spokesman declined to say whether the decision was partly motivated by the murder of the Saudi journalist, not surprisingly, Norway’s announcement came a week after its foreign minister called the Saudi ambassador to Oslo with the aim of condemning Khashoggi’s assassination. As a result, the latter seems to imply Norway’s motivations were a mix of both; the Yemeni conflict and Khashoggi’s death.

Denmark and Finland

By following a similar decision made by neighbouring Germany and Norway—despite the fact that US President Trump backed MBS, although the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had assessed that the crown prince was responsible for the order of the killing—Denmark and Finland both announced that they would also stop exporting arms to the KSA.

Emphasising on the fact that they were “now in a new situation”—after the continued deterioration of the already terrible situation in Yemen and the killing of the Saudi journalist—Danish Foreign Minister, Anders Samuelsen, stated that Denmark would proceed to cease military exports to the KSA remarking that Denmark already had very restrictive practices in this area and hoped that this decision would be able to create a “further momentum and get more European Union (EU) countries involved in the conquest to support tight implementation of the Union’s regulatory framework in this area.”

Although this ban is still less expansive compared to German measures—which include the cancelation of deals that had already been approved—Denmark’s cease of goods’ exports will likely crumble the kingdom’s strategy, especially when it comes to technology. Danish exports to the KSA, which were mainly used for both military and civilian purposes, are chiefly from BAE Systems Applied Intelligence, a subsidiary of the United Kingdom’s BAE Systems, which sold technology that allowed Intellectual Property surveillance and data analysis for use in national security and investigation of serious crimes. The suspension thus includes some dual-use technologies, a reference to materials that were purposely thought to have military applications in favour of the KSA.

On the same day Denmark carried out its decision, Finland announced they were also determined to halt arms export to Saudi Arabia. Yet, in contrast to Norway’s approach, Finnish Prime Minister, Juha Sipilä, held that, of course, the situation in Yemen lead to the decision, but that Khashoggi’s killing was “entirely behind the overall rationale”.

Finnish arms exports to the KSA accounted for 5.3 million euros in 2017. Nevertheless, by describing the situation in Yemen as “catastrophic”, Sipilä declared that any existing licenses (in the region) are old, and in these circumstances, Finland would refuse to be able to grant updated ones. Although, unlike Germany, Helsinki’s decision does not revoke existing arms licenses to the kingdom, the Nordic country has emphasized the fact that it aims to comply with the EU’s arms export criteria, which takes particular account of human rights and the protection of regional peace, security and stability, thus casting doubt on the other European neighbours which, through a sense of incoherence, have not attained to these values.

European Parliament

Speaking in supranational terms, the European Parliament agreed with the latter countries and summoned EU members to freeze arms sales to the kingdom in the conquest of putting pressure on member states to emulate the Germany’s decision.

By claiming that arms exports to Saudi Arabia were breaching international humanitarian law in Yemen, the European Parliament called for sanctions on those countries that refuse to respect EU rules on weapons sales. In fact, the latest attempt in a string of actions compelling EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini to dictate an embargo against the KSA, including a letter signed by MEPs from several parties.

Rapporteur for a European Parliament report on EU arms exports, Bodil Valero said: "European weapons are contributing to human rights abuses and forced migration, which are completely at odds with the EU's common values." As a matter of fact, two successful European Parliament resolutions have hitherto been admitted, but its advocates predicted that some member states especially those who share close trading ties with the kingdom are deep-seated, may be less likely to cooperate. Fact that has eventually occurred.

COUNTRIES THAT HAVE NOT CEASED ARMS SELLING

France

In contrast to the previously mentioned countries, other European states such as France, UK and Spain, have approached the issue differently and have signalled that they will continue “business as usual”.

Both France and the KSA have been sharing close diplomatic and commercial relations ranging from finance to weapons. Up to now, France relished the KSA, which is a bastion against Iranian significance in the Middle East region. Nevertheless, regarding the recent circumstances, Paris now faces a daunting challenge.

Just like other countries, France Foreign Minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, announced France condemned the killing “in the strongest terms” and demanded an exhaustive investigation. "The confirmation of Mr. Jamal Khashoggi's death is a first step toward the establishment of the truth. However, many questions remain unanswered," he added. Following this line, France backed Germany when sanctioning the 18 Saudi citizens thus mulling a joint ban from the wider visa-free Schengen zone. Nevertheless, while German minister Altmeier summoned other European countries to stop selling arms to Riyadh—until the Saudi authorities gave the true explanation on Khashoggi’s death—, France refused to report whether it would suspend arms exports to the KSA. “We want Saudi Arabia to reveal all the truth with full clarity and then we will see what we can do,” he told in a news conference.

In this context, Amnesty International France has become one of Paris’ biggest burdens. The organization has been putting pressure on the French government for it to freeze arms sales to the realm. Hence, by acknowledging France is one of the five biggest arms exporters to Riyadh—similar to the Unites States and Britain—Amnesty International France is becoming aware France’s withdrawal from the arms sales deals is crucial in order to look at the Yemeni conflict in the lens of human rights rather than from a non-humanitarian-geopolitical perspective. Meanwhile, France tries to justify its inaction. When ministry deputy spokesman Oliver Gauvin was asked whether Paris would mirror Berlin’s actions, he emphasized the fact that France’s arms sales control policy was meticulous and based on case-by-case analysis by an inter-ministerial committee. According to French Defence Minister Florence Parly, France exported 11 billion euros worth of arms to the kingdom from 2008 to 2017, fact that boosted French jobs. In 2017 alone, licenses conceivably worth 14.7 billion euros were authorized. Moreover, she went on stating that those arms exports take into consideration numerous criteria among which is the nature of exported materials, the respect of human rights, and the preservation of peace and regional security. "More and more, our industrial and defence sectors need these arms exports. And so, we cannot ignore the impact that all of this has on our defence industry and our jobs," she added. As a result, despite President Emmanuel Macron has publicly sought to devalue the significance relations with the KSA have, minister Parly, seemed to suggest the complete opposite.

Anonymously, a government minister held it was central that MBS retained his position. “The challenge is not to lose MBS, even if he is not a choir boy. A loss of influence in the region would cost us much more than the lack of arms sales”. Notwithstanding France’s ambiguity, Paris’ inconclusive attitude is indicating France’s clout in the region is facing a vulnerable phase. As president Macron told MBS at a side-line G20 summit conversation in December last year, he is worried. Although the context of this chat remains unclear, many believe Macron’s intentions were to persuade MBS to be more transparent as a means to not worsen the kingdom’s reputation and thus to, potentially, dismantle France´s bad image.

United Kingdom

As it was previously mentioned, the United Kingdom took part in the joint statement carried out also by France and Germany through its foreign ministers which claimed there was a need for further explanations regarding Khashoggi’s killing. Yet, although Britain’s Foreign Office said it was considering its “next steps” following the KSA’s admission over Khashoggi’s killing, UK seems to be taking a rather similar approach to France—but not Germany—regarding the situation.

In 2017, the UK was the sixth-biggest arms dealer in the world, and the second-largest exporter of arms to the KSA, behind the US. This is held to be a reflection of a large spear in sales last year. After the KSA intervened in the civil war in Yemen in early 2015, the UK approved more than 3.5billion euros in military sales to the kingdom between April 2015 and September 2016.

As a result, Theresa May has been under pressure for years to interrupt arms sales to the KSA specially after human rights advocates claimed the UK was contributing to alleged violations of international humanitarian law by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen. Adding to this, in 2016, a leaked parliamentary committee report suggested that it was likely that British weapons had been used by the Saudi-led coalition to violate international law, and that manufactured aircraft by BAE Systems, have been used in combat missions in Yemen.

Lately, in the context of Khashoggi’s death things have aggravated and the UK is now facing a great amount of pressure, mainly embodied by UK’s main opposition Labour party which calls for a complete cease in its arms exports to the KSA. In addition, in terms of a more international strain, the European Union has also got to have a say in the matter. Philippe Lamberts, the Belgian leader of the Green grouping of parties, said that Brexit should not be an excuse for the UK to abdicate on its moral responsibilities and that Theresa May had to prove that she was keen on standing up to the kind of atrocious behaviour shown by the killing of Khashoggi and hence freeze arms sales to Saudi Arabia immediately.

Nonetheless, in response and laying emphasis on the importance the upholding relation with UK’s key ally in the Middle East has, London has often been declining calls to end arms exports to the KSA. Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt defended there will be “consequences to the relationship with Saudi Arabia” after the killing of Khashoggi, but he has also pointed out that the UK has an important strategic relationship with Riyadh which needs to be preserved. As a matter of fact, according to some experts, UK’s impending exit from the EU has played a key role. The Campaign Against Arms Trade (CAAT) claims Theresa May’s pursuit for post-Brexit trade deals has seen an unwelcome focus on selling arms to some of the world's most repressive regimes. Nevertheless, by thus tackling the situation in a similar way to France, the UK justifies its actions by saying that it has one of the most meticulous permitting procedures in the world by remarking that its deals comprehend safeguards that counter improper uses.

Spain

After Saudi Arabia’s gave its version for Khashoggi’s killing, the Spanish government said it was “dismayed” and echoed Antonio Guterres’ call for a thorough and transparent investigation to bring justice to all of those responsible for the killing. Yet, despite the clamour that arose after the murder of the columnist, just like France and the UK, Spain’s Prime Minister, Pedro Sánchez, defended arms exporting to the KSA by claiming it was in Spain’s interest to keep selling military tools to Riyadh. Sanchez held he stood in favour of Spain’s interests, namely jobs in strategic sectors that have been badly affected by “the drama that is unemployment". Thusly, proclaiming Spain’s unwillingness to freeze arms exports to the kingdom. In addition, even before Khashoggi’s killing, Sanchez's government was subject to many critics after having decided to proceed with the exporting of 400 laser-guided bombs to Saudi Arabia, despite worries that they could harm civilians in Yemen. Notwithstanding this, Sánchez justified Spain’s decision in that good ties with the Gulf state, a key commercial partner for Spain, needed to be kept.

As a matter of fact, Spain’s state-owned shipbuilder Navantia, in which 5,500 employees work, signed a deal in July last year which accounted for 1.8 billion euros that supplied the Gulf country with five navy ships. This shipbuilder is situated in the southern region of Andalusia, a socialist bulwark which accounts for Spain's highest unemployment estimates and which has recently held regional elections. Hence, it was of the socialist president’s interest to keep these constituencies pleased and the means to this was, of course, not interrupting arms deals with the KSA.

As a consequence, Spain has recently been ignoring the pressures that have arose from MEP’s and from Sanchez’s minorities in government—Catalan separatist parties and far-left party Podemos— which demand a cease in arms exporting. For the time being, Spain will continue business with the KSA as usual.

CONCLUSION