En la imagen

A Belt and Road Initiative Forum taking place in China in 2017 [BRI]

The Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), sometimes referred as the 21st century New Silk Road, is one of the “most ambitious” infrastructure projects ever conceived: The vast collection of development and investment initiatives would stretch from East Asia to Europe, significantly expanding China’s economic and political influence. The variety of projects are discussed in the BRI summits, which are a series of conferences in which business leaders, diplomats, advisors, lobbyists, and other high-level representatives share a common platform that facilitates international cooperation for development in the regions involved in the initiative. The main objective of such summits is to create a network among the attending nations of trust, mutual understanding, and economic cooperation. The summit is held every year in Hong Kong ever since the first summit took place in 2016. The seventh edition, being the latest, was concluded on September 1st, 2022.

It is relevant to distinguish the summits (that constitute the main object of our study) from the Belt and Road Forums for International Cooperation. While the latter aims to provide an occasion for the discussion of political and economic views, the summits focus on the actual development of the BRI projects in terms of infrastructure, investment, and all other aspects in a more practical and real manner.

The Initiative was created by China’s Xi Jinping in 2013 and, ever since, Chinese interests in the Indo-Pacific region have only gained increased importance in the geopolitical agenda of the East Asian nation. Moreover, the BRI functions for China as a mechanism to engage with the international community without projecting an intrusive image on the internal affairs of other states. With the increasing political and economic relevance of China, it is only natural to see it engaging in different regions of the world. Ultimately, the BRI has the aim to connect China with the rest of the world—mainly Eurasia—so that the country has a stronger presence compared to the other global powers.

Despite the international importance of the Belt and Road, there is no easy way to access specific details about the summits. Documents on the issue are predominantly written in Chinese, and the data which is available in other languages is mostly incomplete. As an example, the attendee lists are only available for the 2022 and 2021 summits; before that, there is no information on any Chinese official website.

This paper contributes to fill the very gap mentioned above. Because of this, we believe that this paper plays a part in reducing the transparency associated with the BRI summits. When discussing the attendance of member countries with respect to different regions it is possible to distinguish a specific geographic pattern and observe the importance—or lack thereof—of the project in different areas. This information can also throw more light on the current geopolitical situation concerning the BRI. Moreover, the participation of different global powers demonstrates their position towards China and its increasing international influence.

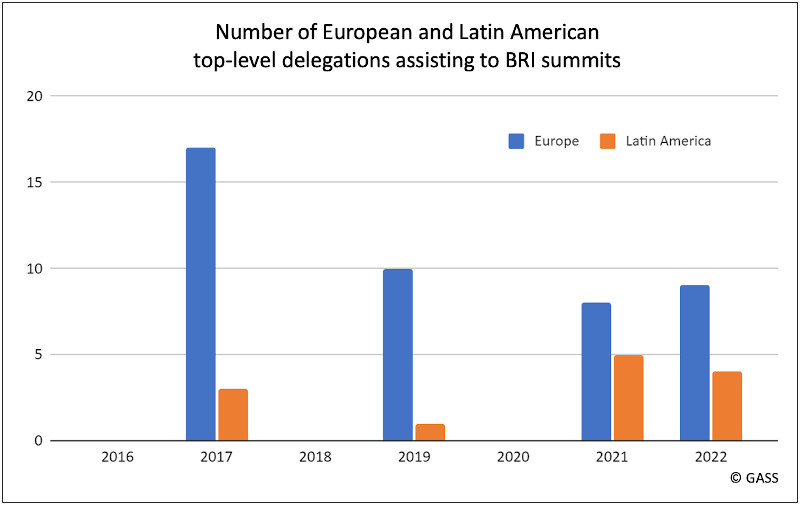

For this analysis to be possible, this paper will be divided into three different sections, where specific regions will be addressed in a chronological manner, with respect to the participation of nations in the summits. First, the paper will discuss Latin America, followed by Europe. Next, the paper will state the major findings of the analysis. Throughout the analysis the focus will be set on the attendance of high-level government officials of the different delegations, such as heads of state, government, and ministers.

Latin America and Europe were chosen as the subjects of study because of the strategic and economic importance they hold for China. On the one hand, Latin America is one of the biggest markets for raw materials and natural resources which are vital to maintaining Chinese manufacturing. Latin America is also an important hub for maritime commerce which can be exploited by China through the Maritime Belt and Road (it refers to the Indo- Pacific sea routes, part of the Belt and Road Initiative, that comprise from Southeast Asia all over to South Asia, Africa and the Middle East.) Europe is, as well, the target of our paper because it is an area where China can potentially exert economic influence, which in turn can bring it politically closer to China and distance it from the North Atlantic Alliance.

Latin American presence at the BRI summits

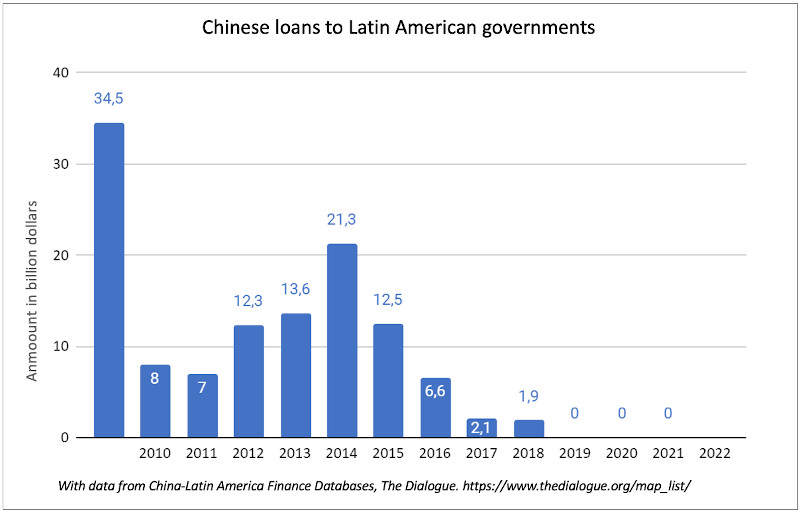

The Chinese economic interests have intensified in Latin America with the expansion of the Belt and Road Initiative over the years. Despite this, the region has demonstrated a lax response to greater Chinese participation in its economies. This can be attributed to the economic influence of the United States in the region. Moreover, the historical political influence of the US in Latin America represents an important factor that should be taken into consideration. Traditionally, the region has not challenged the United States’ dominance and the BRI is no exception. Yet there is a possibility for a slow but steady inclination of different Latin American countries that have been hedging between the two global powers.

The first BRI summit, held in 2016, is difficult to analyze since there are no official numbers stating the amount of attendees who were present. There is no possible way to find this information through official sources since the Chinese government does not provide the numerical and qualitative data neither in their official websites nor in the official reports of the summits. The same phenomenon occurs for the next four summits, yet there are some secondary sources that shed light on the attendance of some top-level officials of the region.

While for the second summit (2017) there is no official attendance list, The Diplomat published an article in which all nations who were represented by a head of state or a minister were mentioned. In the case of Latin America, only Chile and Argentina were present at both the summit and the forum with Michelle Bachelet and Mauricio Macri respectively. Brazil also attended the second edition of the BRI summit, yet it is not specified at what level of government they were involved.

The case for the third summit (2018) is the same as the one for the 2016 edition. For this year’s edition there is also no official information available, yet the official BRI report mentions the presence of around 100 delegations without specifying their nature. What it is known is that 80% of the attendees were service providers, investors, and project owners. The fourth edition of the summit (2019) saw almost nonexistent Latin American involvement. The only confirmed head of state that was present at the summit came from Chile, while there were no other regional delegations involved.

The fifth summit (2020) was in a very different format because of the outbreak of the Coronavirus. This year’s summit was held online, which is the possible cause for the official attendee list to be missing. The official reports mention that around 80 delegations attended the summit and only 22% of the participants were government officials. While the attendance was numerous, there were no in situ meetings with any Chinese official or company because of the heavy impact of the pandemic worldwide.

On the other hand, the sixth summit (2021) saw the participation of five countries (Barbados, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Uruguay) so it can be clearly seen that the involvement fell from 2021 to 2022. The seventh and latest summit (2022) saw the participation of only four Latin American countries (Barbados, Brazil, Chile, and Venezuela).

There are no evident reasons for the dismal participation rate of the Latin American countries. Among the main regional powers of Latin America, only two (Brazil and Chile) attended the seventh edition (2022) of the Belt and Road summit hosted in Hong Kong. Moreover, nations such as Panama, Peru, and Nicaragua, where there is great potential for Chinese development of infrastructure owing to their strategic location and abundant resources, were absent from the summit.