Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Entradas con Categorías Global Affairs Orden mundial, diplomacia y gobernanza .

Con una producción petrolera bajo mínimos, el régimen de Maduro ha echado mano del metal precioso para pagar los servicios de Teherán

° Sin más créditos de China o Rusia, Caracas consolidó en 2020 la renacida relación con los iraníes, encargados de intentar reactivar las paralizadas refinerías del país

° En el último año, cargueros despachados por Irán han llevado a la nación caribeña más de 5 millones de barriles de gasolina, así como productos para su supermercado Megasis

° La implicación de entidades relacionadas con la Guardia Revolucionaria, declarada grupo terrorista por Washington, dificulta cualquier gesto hacia la Administración Biden

► La vicepresidenta venezolana y el viceministro de Industria iraní inauguran el supermercado Megasis en Caracas, en julio de 2020 [Gob. de Venezuela]

INFORME SRA 2021 / María Victoria Andarcia [versión en PDF]

La relación de Venezuela con potencias extrahemisféricas ha estado caracterizada en el último año y medio por la reanudación de la estrecha vinculación con Irán ya vista durante las presidencias de Hugo Chávez y Mahmud Ahmadineyad. Agotadas las posibilidades de financiación facilitadas por China (no concede créditos a Caracas desde 2016) y por Rusia (su interés petrolero en Venezuela, a través de Rosneft, se vio especialmente constreñido en 2019 por las sanciones de la Administración Trump a los negocios de Pdvsa), el régimen de Nicolás Maduro llamó de nuevo a la puerta de Irán.

Y Teherán, otra vez cercado por las sanciones de Estados Unidos, como ocurriera durante la era de Ahmadineyad, ha vuelto a ver en la alianza con Venezuela la ocasión de plantar cara a Washington, al tiempo que saca algún rendimiento económico en tiempos de gran necesidad: cargamentos de oro, por valor al menos de 500 millones de dólares, según Bloomberg, habrían salido de Venezuela en 2020 como pago de los servicios prestados por Irán. Si los créditos de China o Rusia eran a cambio de petróleo, ahora el régimen chavista debía además echar mano del oro, pues la producción de la estatal Pdvsa estaba bajo mínimos históricos, con 362.000 barriles diarios en el tercer trimestre del año (Chávez tomó la compañía con una producción de 3,2 millones de barriles diarios).

El cambio de pareja se simbolizó en febrero de 2020 con la llegada de técnicos iraníes para poner en marcha la refinería de Armuy, abandonada el mes anterior por los expertos rusos. La falta de inversión había llevado al descuido del mantenimiento de las refinerías del país, lo que estaba provocando una gran escasez de gasolina y largas filas en las estaciones de servicio. La asistencia iraní apenas lograría mejorar la situación refinadora, y Teherán tuvo que suplir esa ineficiencia con el envío de cargueros de gasolina. Asimismo, la escasez de alimentos ofreció otra vía de auxilio para Teherán, que también despachó barcos con comestibles.

Gasolina y alimentos

La relación venezolano-iraní, que sin eliminarse del todo se había reducido durante la presidencia de Hasán Rohaní, al focalizarse esta en la negociación internacional del acuerdo nuclear que se alcanzaría en 2015 (conocido como JCPOA por sus siglas en inglés), se reanudó a lo largo de 2019. En abril de ese año la controvertida aerolínea iraní Mahan Air recibió permisos de operaciones en Venezuela para cubrir la ruta Teherán-Caracas. Aunque la aerolínea no ha comercializado la ruta aérea, sí ha fletado varios vuelos a Venezuela a pesar del cierre del espacio aéreo territorial ordenado por Maduro debido a la pandemia de Covid-19. Las operaciones de Mahan Air sirvieron para transportar a los técnicos iraníes que iban a emplearse en los esfuerzos de reiniciar la producción de gasolina en las refinerías del complejo de Paraguaná, así como material necesario para esas tareas.

Esas y otras gestiones habrían estado preparadas por la embajada de Irán en Venezuela, que desde diciembre de 2019 está dirigida por Hojatolá Soltani, alguien conocido por “mezclar la política exterior de Irán con las actividades” del Cuerpo de la Guardia Revolucionaria Islámica (IRGC), según el investigador Joseph Humire. Este considera que Mahan Air habría realizado unos cuarenta vuelos en la primera mitad de 2020.

De la misma manera, Irán estuvo enviando múltiples buques de combustible a Venezuela para hacer frente a la escasez de gasolina. El primer envío llegó en una flotilla de tanqueros que, desafiando las sanciones de Estados Unidos, entraron en aguas venezolanas entre el 24 y el 31 de mayo, transportando en conjunto 1,5 millones de barriles de gasolina. En junio llegó otro buque con unos estimados 300.000 barriles, y otros tres aportaron 820.000 barriles entre el 28 de septiembre y el 4 de octubre. Entre diciembre de 2020 y enero de 2021 otra flotilla habría transportado 2,3 millones de barriles. A ese total de al menos 5 millones de barriles de gasolina habría que sumar la llegada 2,1 millones de barriles de condensado para aplicarse como diluyente del petróleo extrapesado venezolano.

Además de combustible, Irán también ha enviado en este tiempo suministros médicos y alimentos para ayudar a combatir emergencia humanitaria que sufre el país. Así, resulta importante destacar la apertura del supermercado Megasis, a la que se vincula con la Guardia Revolucionaria, cuerpo militar iraní que la Administración Trump incluyó en el catálogo de grupos terroristas. El establecimiento comercial vende productos de marcas propiedad del ejercito iraní, como Delnoosh y Varamin, que son dos de las subsidiarias de la compañía Ekta, supuestamente creada como un fideicomiso de seguridad social para veteranos militares iraníes. La cadena de supermercados Ekta se encuentra subordinada al Ministerio de Defensa iraní y a las Fuerzas Armadas de Logística, entidad sancionada por Estados Unidos por su papel en el desarrollo de misiles balísticos.

El oro y Saab

Esta actividad preocupa a Estados Unidos. Un reporte del Atlantic Council detalla cómo las redes respaldadas por Irán apuntalan al régimen de Maduro. El ministro de petróleo venezolano, Tareck El Aissami ha sido identificado como el actor clave de la red ilícita. Éste presuntamente acordó con Teherán la importación de combustible iraní a cambio de oro venezolano. De acuerdo con la información de Bloomberg antes citada, el Gobierno de Venezuela había entregado a Irán, hasta abril de 2020, alrededor de nueve toneladas de oro con un valor de aproximadamente 500 millones de dólares, a cambio de su asistencia en la reactivación de las refinerías. El oro fue aparentemente trasladado en los vuelos de Mahan Air hacia Teherán.

En las negociaciones pudo haber intervenido el empresario de origen colombiano Alex Saab, que ya centralizó buena parte de las importaciones de alimentos realizadas por el régimen chavista bajo el programa Clap y se estaba implicando en los suministros iraníes de gasolina. Saab fue detenido en junio de 2020 en Cabo Verde cuando su avión particular repostaba en un aparente vuelo a Teherán. Solicitado a Interpol por Estados Unidos como principal testaferro de Maduro, el proceso de extradición sigue abierto.

Las entidades participantes en buena parte de estos intercambios están sancionadas por Oficina de Control de Activos Extranjeros del Tesoro estadounidense por su conexión a la IRGC. La capacidad de la IRGC de operar en Venezuela se debe al alcance de la red de soporte de Hezbolá, organización señalada como terrorista por Estados Unidos y la Unión Europea. Hezbolá ha logrado infiltrar las comunidades expatriadas libanesas de Venezuela, dando paso a Irán para crecer su influencia en la región. Esos vínculos dificultan cualquier gesto que Caracas pueda intentar para propiciar cualquier desescalada por parte de la nueva Administración Biden de las sanciones aplicadas por Washington.

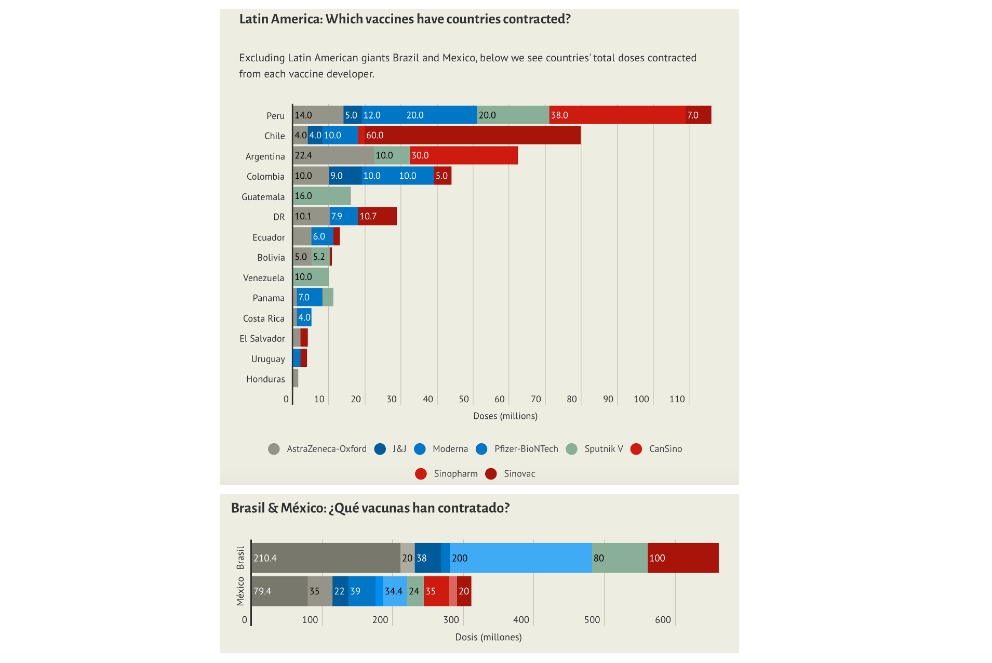

Pekín ya no es solo socio comercial y otorgador de créditos para infraestructuras: se pone a la par de Occidente en excelencia farmacéutica y proveedor sanitario

° Solo Perú, Chile y Argentina han contratado más dosis chinas y rusas; en Brasil y México predominan las de EEUU y Europa, como en el resto de los países de la región

° Huawei logra entrar en el concurso del 5G brasileño a cambio de vacunas; Pekín las ofrece a Paraguay si abandona su reconocimiento a Taiwán

° Además de los ensayos clínicos que hubo en varias naciones en la segunda mitad de 2020, Argentina y México van a producir o envasar Sputnik V a partir del mes de junio

► Llegada de un cargamento de vacunas Sputnik V a Venezuela, en febrero de 2021 [Palacio de Miraflores]

INFORME SRA 2021 / Emili J. Blasco [versión en PDF]

La vacunación en Latinoamérica se está haciendo sustancialmente con preparados desarrollados en Estados Unidos y Europa, aunque la atención mediática haya privilegiado las dosis procedentes de China y Rusia. La particular diplomacia de las vacunas ejecutada a lo largo de los últimos meses por Pekín y Moscú –que con fondos públicos han promovido la exportación de inyecciones, por delante de las necesidades de sus propios habitantes– ha sido ciertamente activa y ha logrado dar la impresión de una influencia mayor de la real, con la promesa muchas veces de volúmenes de suministros que raras veces se han cumplido en sus plazos.

Cuando, a partir de junio, inmunizada ya gran parte de los estadounidenses, la Administración Biden se vuelque en hacer su aportación de vacunas a la región, el desequilibrio a favor de fórmulas de los laboratorios “occidentales” –también utilizadas básicamente en los acopios del sistema Covax de Naciones Unidas– será aún mayor. No obstante, el desarrollo de la crisis sanitaria en el último año habrá servido para consolidar el pie puesto por China y Rusia en América Latina.

Hasta la fecha, solo Perú, Chile y Argentina han contratado más vacunas de China (CanSino, Sinopharm y Sinovac) y Rusia (Sputnik V) que de Estados Unidos y Europa (AstraZeneca, J&J, Moderna y Pfizer). En el caso de Perú, de los 116 millones de dosis comprometidas, 51 corresponden a laboratorios europeos y/o estadounidenses, 45 millones a los chinos y 20 millones al ruso. En el caso de Chile, de los 79,8 millones de dosis, 18 millones son vacunas del primer grupo, mientras que 61,8 millones son chinas. Por lo que afecta a Argentina, de los 62,4 millones de dosis reservadas, 22,4 millones son “occidentales”, 10 millones rusas y 30 millones chinas. Son datos de AS/COA, que sigue un detallado cómputo de diversos aspectos de la evolución de la crisis sanitaria en Latinoamérica.

En cuanto a los dos mayores países de la región, la preferencia por las fórmulas de EEUU y Europa es notoria. De los 661,4 millones de dosis apalabradas por Brasil, 481,4 tienen esa procedencia, frente a 100 millones de dosis chinas y 80 millones de Sputnik V (además, no está claro que estas últimas acaben llegando, dada el reciente rechazado a su autorización por parte de los reguladores brasileños). De los 310,8 millones contratados por México, 219,8 millones son de vacunas “occidentales”, 67 millones de vacunas chinas y 24 millones de Sputnik V.

Tablas: reproducción de AS/COA, base de datos online, información a 31 de marzo de 2021

Ensayos y producción

Las vacunas de China y Rusia no eran desconocidas en la opinión pública latinoamericana, pues en la segunda mitad de 2020 fueron noticia con frecuencia a raíz de los ensayos clínicos que se llevaron a cabo en algunos países. Sudamérica presentaba un especial interés para los principales laboratorios del mundo, ya que acogía una alta incidencia de la epidemia junto con cierto desarrollo médico que permitía un serio seguimiento de la eficacia de los preparados, compatible con un nivel de necesidad económica que facilitaba contar con miles de voluntarios para las pruebas. Eso hizo que la región centrara el campo de ensayos clínicos mundiales de las principales vacunas anti Covid-19, siendo Brasil el epicentro de la carrera en la experimentación. Además de las pruebas llevadas a cabo por Johnson & Johnson en seis países, y de Pfizer y Moderna en dos, Sputnik V se experimentó en tres (Brasil, México y Venezuela) y en dos lo hicieron Sinovac (Brasil y Chile) y Sinopharm (Argentina y Perú).

La experimentación, no obstante, se debía a acuerdos particulares entre laboratorios, que apenas exigía implicación de las autoridades sanitarias o políticas del país en cuestión. El compromiso de determinados gobiernos con las vacunas de China y Rusia vino con las negociaciones de compra y luego con su consiguiente autorización de uso, último paso que no siempre se ha producido. Una ulterior alianza en el caso de Sputnik V ha sido el proyecto de Argentina de producir en su territorio el preparado ruso a partir del próximo mes de junio, para vacunación propia y reparto a países vecinos, así como el de México para el envasado de las dosis, también a partir de junio. Argentina fue el primer país en registrar y aprobar Sputnik V, utilizando una información que luego ha compartido con otros países de la región. El movimiento de México ha sido interpretado como un modo de presionar a Estados Unidos para que liberalice cuanto antes la exportación de sus vacunas.

También China ha ejercido presiones sobre algunos países sudamericanos. Ha aprovechado la extrema necesidad de vacunas de Brasil para forzar que el Gobierno de Jair Bolsonaro tenga que admitir que Huawei opte al concurso para la red de 5G brasileña, a pesar de haber vetado inicialmente a la empresa china. Igualmente, Pekín parece haber prometido vacunas a Paraguay a cambio de que este país deje de reconocer a Taiwán. Por lo demás, el Gobierno chino promedió el año pasado un crédito de mil millones de dólares para la adquisición de material sanitario, como ha advertido el jefe del Comando Sur estadounidense, llamando la atención sobre el uso de la crisis que está haciendo China para lograr más penetración en el hemisferio.

Consolidación

Sea cual sea el mapa final de la aplicación de cada preparado en el proceso de vacunación, lo cierto es que sobre todo Pekín, pero de algún modo también Moscú, han logrado una importante victoria, por más que sus vacunas puedan quedar muy por detrás en el número total de dosis inyectadas en Latinoamérica. En una región acostumbrada a identificar a Estados Unidos y Europa con la capacidad científica y el alto desarrollo médico y farmacéutico, por primera vez se ve a China no ya como origen de productos baratos y de confección poco sofisticada, sino a la par en investigación y eficacia sanitaria. Más allá de la exitosa gestión que ha hecho Pekín de la pandemia, que puede relativizarse considerando el carácter autoritario de su sistema político, China surge como un país puntero, capaz de alcanzar una vacuna tan rápidamente como Occidente y, en cierta forma, homologable a este. La imagen de Rusia queda algo por debajo, pero Sputnik V permite consolidar el “regreso” ruso a una posición de referencia que había perdido absolutamente en recientes décadas.

A raíz de la emergencia por Covid-19, en el imaginario colectivo latinoamericano China ya no constituye solo un factor de comercio, de construcción de infraestructuras y de otorgador de créditos para el desarrollo de estas, sino que asienta su penetración como una potencia con dimensiones plenas, también en lo referente a un elemento central en la vida de los individuos como es la superación de la pandemia.

Y es que los países latinoamericanos han sufrido la crisis sanitaria y económica del coronavirus como ninguna otra región del mundo. Con el 8,2% de la población mundial, para octubre de 2020 acogía el 28% de los casos positivos globales por Covid-19 y el 34% de las muertes. El agravamiento de la situación luego en países como India pudo modificar algo esos porcentajes, pero la región ha mantenido importantes focos de infección, como Brasil, seguido de México y Perú. Para hacer frente a esta situación, Latinoamérica recibe dos tercios de la ayuda mundial del FMI por la pandemia: la región cuenta con 17 millones más de pobres y no recuperará la anterior renta per cápita hasta 2025, más tarde que el resto del mundo.

![Gacaca trials, a powerful instrument of transitional justice implemented in Rwanda [UNDP/Elisa Finocchiaro]](/documents/16800098/0/Foto_Africa-Peacebuilding_larga.png/14888a0b-3a0c-2ee5-71dc-e75c22249faf?t=1621873383792&imagePreview=1)

ESSAY / María Rodríguez Reyero

One of the main questions that arise after a conflict comes to an end is what the reconstruction process should be focused on. Is it more important to forget the past and heal the wounds of a community or to ensure that the perpetrators of violence are fairly punished? Is the concept of peacebuilding in post-conflict societies compatible with justice and the punishment for crimes? Which one should prevail? And most importantly, which one ensures a better and more sustainable future for the already harshly punished inhabitants?

One of the main reasons in defence of the promotion of justice and accountability in post-conflict communities is its significance when it comes to retributive reasons: those who committed such atrocious crimes deserve to get the consequences. The accountability also discourages future degradations, and some mechanisms such as truth commissions and reparations to the victims allow them to have a voice, as potentially cathartic or healing. They may also argue that accountability processes are essential for longer-term peacemaking and peacebuilding. Another reason for pursuing justice and accountability is how the impunity of past crimes could affect the legitimacy of new governments, as impunity for certain key perpetrators will undermine people’s belief in reconstruction and the possibilities for building a culture of respect for rule of law.[1]

On the other hand, peacebuilding, which attempts to address the underlying causes of a conflict and to help people to resolve their disputes rather than aiming for accountability, remains a quite controversial term, as it varies depending on its historical and geographical context. In general terms, peacebuilding encompasses activities designed to solidify peace and avoid a relapse into conflict[2]. According to Brahimi, those are undertaken to reassemble the foundations of peace and provide tools for building up those foundations, more than just focusing on the absence of war[3]. Some of the employed tools to achieve said aims typically include rule of law promotion and with the tools designed to promote security and stability: disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of ex-combatants (DDR), and security sector reform (SSR) and others such as taking custody of and destroying weapons, repatriating refugees, offering advisory and training support for security personnel, monitoring elections, advancing efforts to protect human rights, reforming or strengthening government institutions and promotion of the formal and informal process of political participation.[4]

Those conflict resolution and peacebuilding activities can be disrupted by accountability processes.[5] The concern is that accountability initiatives might even block possible peace agreements and lengthen the dispute as they remove the foundations of the conflict, making flourish bad feelings and resentment amongst the society. The main reason behind this fear is that those likely to be targeted by accountability mechanisms may therefore resist peace deals. This explains why on many occasions and aiming for peace, amnesties have been given to secure peace agreements Likewise, there is a prevailing concern that transitional justice tools may reduce the impact in the short term the durability of a peace settlement as well as the effectiveness of further peace-building actions.

Despite the arguments in favour and against both mechanisms, the reality is that in practice post-conflict societies tend to strike a balance between peacebuilding and transitional justice. Both are multifaceted processes that do not rely on one system to accomplish their ends, that frequently converge. However, their activities on occasions collide and are not complimentary. This essay examines one of the dilemmas in building a just and durable peace: the challenging and complex relationship between transitional justice and peacebuilding in countries emerging from conflict.

To do so, this essay takes into consideration Rwanda, a clear example of the triumph of transitional justice, after a tragic genocide in 1994. From April to July 1994, between 800,000 and one million ethnic Tutsis were brutally killed during a 100-day killing spree perpetrated by Hutus[6]. After the genocide, Rwanda was on the edge of total collapse. Entire villages were destroyed, and social cohesion was in utter deterioration. In 2002, Rwanda boarded on the most arduous practice in transitional justice ever endeavoured: mass justice for mass atrocity, to judge and restart a stable society after the bloody genocide. To do so, Rwanda decided to put most of the nation on trial, instead of choosing, as other post-conflict states did (such as Mozambique, Uganda, East Timor, or Sierra Leone), amnesties, truth commissions, selective criminal prosecutions.[7]

On the other hand, Sierra Leone is a clear example of the success of peacebuilding activities, after a civil war that led to the deaths of over 50,000 people and a poverty-stricken country. The conflict faced the Revolutionary United Front (RUF[8]) against the official government, due to a context of bad governance and extensive injustice. It came to an end with the Abuja Protocols in 2001 and elections in 2002. The armed factions endeavoured to avoid any consequences by requesting an amnesty as well as reintegration assistance to ease possible societal ostracism. It was agreed only because the people of Sierra Leone so severely needed the violence to end. However, the UN representative to the peace negotiations stated that the amnesty did not apply to international crimes, President Kabbah asked for the UN’s assistance[9] and it resulted in the birth of Sierra Leone’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL or Special Court).[10]

Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) and transitional justice

Promoting short and longer-term security and stability in conflict-prone and post-conflict countries in many cases requires the reduction and structural transformation of groups with the capacity to engage in the use of force, including armies, militias, and rebel groups. In such situations, two processes are of remarkable benefit in lessening the risk of violence: DDR (disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration) of ex-combatants; and SSR (security sector reform).

DDR entails a range of policies and programs, supporting the return of ex-combatants to civilian life, either in their former communities or in different ones. Even if not all ex-combatants are turned to civilian life, DDR programs may lead to the transfer and training, of former members of armed groups to new military and security forces. The essence of DDR programming and the guarantees it seeks to provide is of utmost importance to ensuring peacebuilding and the possibility of efficient and legitimate governance.

It is undeniable that soldiers are unquestionably opposing to responsibility processes enshrined in peace agreements: they are less likely to cede arms if they dread arrest, whether it is by an international or domestic court. This intensifies their general security fears after the disarming process. In many instances, ex-combatants are integrated into state security forces, which makes the promotion of the rule of law, difficult, as the groups charged with enforcing new laws may have the most to lose through the implicated reforms. It is also likely to lessen citizen reliance on the security forces. The incorporation of former fighters not only in the new military but also in new civilian security structures is common: for example, in Rwanda, the victorious RPF dominated the post-genocide security forces.

While the spectre of prosecutions most obviously may impede DDR processes, there is a lesser possibility that it might provide incentives for DDR, as might happens where amnesty or reduced sentences are offered as inducements for combatants to take part in DDR processes. For them to be effective, the reliability of both the threat of prosecution and the durability of amnesty or other forms of protection are essentials whether it is in national or international courts. Even if this is not related to the promotion of transitional justice processes, it is another example of how it can have a long-term effect on the respect of human rights and the prevention of future breaches.

As previously stated, some DDR and transitional justice processes may share alike ends and even employ similar mechanisms. A variety of traditional processes of accountability and conflict resolution often also seek to promote reconciliation. DDR programs increasingly include measures that try to encourage return, reintegration, and if possible, reconciliation within communities. This willingness of victims to forgive and forget could in theory be promoted through a range of reconciliation processes like the ones promoted by transitional justice with the assistance of tools like truth commissions, which facilitate a dialogue that allows inhabitants to move forward while accepting the arrival of former perpetrators.

The triumph of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) in 1994 finally put an end to the genocide in the country. The new government focused on criminal accountability for the 1994 genocide and as a result of this prioritization, the needs of survivors have not been met completely Rwanda is the paradigm and perfect example of prosecution of perpetrators of mass atrocity by the employment of transitional justice mechanisms, that were kept separated from DDR programs in order not to interfere with the attribution of responsibilities.[11] The Rwandan one is a case where DDR largely worked notwithstanding firmly opposing amnesty. Proof of this outstanding DDR success is how Rwanda has managed to successfully reintegrate around 54,000 combatants since 1995 thanks to the work of the Rwandan Demobilization and Reintegration Commission (RDRC). Another clear evidence of the effectiveness of DDR methods in Rwanda is the reintegration of child soldiers. Released child soldiers were installed in a special school (Kadogo School), which started with 2,922 children. By 1998 when it closed, the RDRC reported that 73% of its students had reunited with one or both parents successfully.[12]

On the other hand, Sierra Leone’s case on DDR was quite different from Rwanda’s success, as Sierra Leone's conflict involved the prevalence of children associated with armed forces and groups (CAAFG). By the time the civil war concluded in 2002, data from UNICEF estimates that roughly 6,845 children have been demobilized,[13] although the actual number could be way higher. Consequently, the DDR program in Sierra Leone is essentially focused on the reintegration of young soldiers, an initiative led by UNICEF with the backing of some local organizations, as the National Committee on DDR (NCDDR)of Sierra Leone. Nonetheless, in practice, Sierra Leone's military did not endure these local guidelines, and as a result the participation of children in the process often had to be arranged by UNICEF peacekeepers in most cases. In addition to that initial local reluctance, some major quandaries aroused when it came to the reintegration of children in the new peace era in Sierra Leone, mainly due to the tests and requirements for children to have access to DDR programs, such as to present a weapon and demonstrate familiarity with it.[14] As a result, many CAAFG were excluded from the DDR process, primarily girls who were predominantly charged with non-directly military activities such as “to carry loads, do domestic work, and other support tasks.”[15]

Thus, the participation of girls in Sierra Leone’s DDR was particularly low and many never even received support. While it is not clear how many girls were abducted during the war, data from UNICEF calculates that out of the 6,845 overall children demobilized, 92% were boys and only 8% were girls. The Women's Commission for Refugee Women and Children has pointed out that as many as 80 per cent of rebel soldiers were between the ages of 7 and 14, and escapees from the rebel camps reported that the majority of camp members were young captive girls.[16] Research also reported that 46% of the girls who were excluded from the program confirmed that not having a weapon was the reason for exclusion. In other cases, girls were not permitted by their husbands to go through the DDR,2 whilst others chose to opt-out themselves due to worry of stigmatization back in their neighbourhoods.[17] It is worth noting that many of those who succeeded to go through the demobilization phase “reported sexual harassment at the ICCs, either by male residents or visiting adult combatants”, while others experienced verbal abuse, beatings, and exclusion in their communities.[18]

Another problem that underlines the importance of local leadership in DDR processes is that the UN-driven DDR program lets children decide to receive skill training rather than attending school if they were above 15 years. However, the program provided little assistance with finding jobs upon completion of the apprenticeship. Besides, little market examination was done to learn the demands of the local economy where children were trying to reintegrate into, so they are far more than the Sierra Leonean economy could absorb, which resulted in a lack of long-term employment for demobilized child soldiers. Studies by the Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers[19] and Human Rights Watch[20] revealed that adolescents who had beforehand been part of armed organizations during the war in Sierra Leone were re-recruited in Liberia or Congo because of the frustration and the lack of economic options for them back in Sierra Leone.

Promotion of the rule of law and its contributions to peacebuilding

Amongst many others, the promotion of the rule of law in post-conflict countries is a fundamental factor in peacebuilding procedures. It contributes to eradicating many of the causes of emerging conflicts, such as corruption, disruption of law... Even if it may seem contradictory, peacebuilding activities in support of the rule of law may become contradictory to transitional justice. Sometimes processes of transitional justice may displace resources, both capital, and human, that might otherwise be given to strengthening the rule of law. For instance, in Rwanda, it has been claimed that the resources invested in the development and assistance to national courts should have been equal to those committed to the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), and the extent to which trials at the ICTR have had an impact domestically remains to be seen.

However, transitional justice also presents other challenges to the reconstruction of the rule of law. Transitional justice processes might also destabilize critically imperfect justice sectors, making it more difficult to improve longer-term rule of law. They can stimulate responses from perpetrators which could destabilize the flimsy harmony of nascent governments, as they might question its legitimacy or actively attempt to undermine the authority of public institutions. Judging former perpetrators is an arduous task that is also faced with corruption and lack of personal and resources on many occasions. Additionally, the effort by national courts to prosecute criminals is an undue burden on the judicial system, which is severely damaged after a conflict and in many cases not ready to confront such atrocious crimes and the long processes they entail. Processes to try those accused of genocide in Rwanda, where the national judicial system was devasted after the genocide, have put great pressure on the judicial system, and the lack of capacity has resulted that many arrested remained in custody for years without having been convicted or even having had their cases heard, in the majority of the cases in appalling prison conditions. Such supposed accountability initiatives may have a counterproductive effect, contributing to a sense of impunity and distrust in justice processes.

Despite the outlined tensions, transitional justice and rule of law promotion are also capable to work towards the same ends. A key goal of transitional justice is to contribute to the rebuilding of a society based on the rule of law and respect for human rights, essential for durable peace. The improvement of a judiciary based on transparency and equality is strictly linked to the ability of a nation to approach prior human rights infringements after a conflict.[21] Both are potentially mutually reinforcing in practice if complementarities can be exploited. Consequently, rule of law advancement and transitional justice mechanisms however combine in some techniques.

To start with, the birth of processes to address past transgressions perpetrated during the conflict, both international and domestic processes, can help to restore confidence in the justice sector, especially when it comes to new arising democratic institutions. The use of domestic courts for accountability processes helps to place the judiciary at the centre of the promotion and protection of human rights of the local population, which contributes to the intensification of trust not only in the judicial system but also in public institutions and the government in general. Government initiation of an accountability process may indicate an engagement to justice and the rule of law beforehand. Domestically-rooted judicial processes, as well as other transitional justice tools, such as commissions of inquiry, may also support the development of mechanisms and rules for democratic and fair institutions by establishing regularized procedures and rules and promoting discussions rather than violence as a means of resolving differences and a reassuring population that their demands will be met in independent, fair and unbiased fora, be this a regular court or an ad hoc judicial or non-judicial mechanism. This is not to assume that internationally driven transitional justice mechanisms do not have a role to play in the development of the rule of law in the countries for which they have been established, as the hybrid tribunal of Sierra Leone demonstrates.[22]

In general terms, the refusal of impunity for perpetrators and the reformation of public institutions are considered the basic tools for the success of transitional justice. Transcending the strengthening of the judiciary, different reform processes can strengthen rule of law and accountability: institutions that counteract the influence of certain groups (including the government) like human rights commissions or anti-corruption commissions, may contribute to the establishment of a strong institutional and social structure more capable of confronting social tensions and hence evade the recurrence to conflict.[23]

Achieving an effective transitional justice strategy in Rwanda is an incredible challenge taking into consideration the massive scale as well as the harshness of the genocide, but also because of the economic and geographical limitations that make perpetrators and survivors live together in the aftermath. To facilitate things, other post-conflict states with similarly devastatingly high numbers of perpetrators have opted for amnesties or selective prosecutions, but the Rwandan government is engaged in holding those guilty for genocide responsible, thus strongly advocating for the employment of transitional justice. This is being accomplished through truth commissions, Gacaca traditional courts, national courts, and the international criminal tribunal for Rwanda combined. This underlines the dilemma of whether national or international courts are more efficient in implementing transitional justice.

Gacaca focuses on groups rather than individuals, seeks compromise and community harmony, and emphasizes restitution over forms of punishment. Moreover, it is characterized by accessibility, economy, and public participation. It encourages transparency of proceedings with the participation of the public as witnesses, who gain the truth about the circumstances surrounding the atrocities suffered during the genocide. Also, it provides an economic benefit, as Gacaca courts can try cases at a greater speed than international courts, thus reducing considerably the monetary cost as the number of incarcerated persons waiting for a trial is significantly reduced.

Alongside the strengths of the Gacaca system come flaws that seem to be inherent in the system. Many have come to see the Gacaca as an opportunity to require revenge on enemies or to frighten others with the threat of accusation, instead of injecting a sense of truth and reconciliation: the Gacaca trials have aroused concern and intimidation amongst many sectors of the population. Additionally, the community service prescribed to convicted perpetrators frequently is not done within the community where the crime was committed but rather done in the form of public service projects, which enforces the impression that officials may be using the system to benefit the government instead of helping the ones harmed by the genocide. Another proof of the control of Gacaca trials for benefit of the government is manifested by the prosecutions against critics of the post-genocide regime.

On the other hand, Sierra Leone’s situation is very different from the one in Rwanda. To help restore the rule of law, the Special court settled in Sierra Leone must be seen as a role model for the administration of justice, and to promote deterrence it must be deemed credible, which is one of its main problems.[24] There is little confidence in the international tribunals amongst the local population, as the Court’s nature makes it non-subordinated to the Sierra Leonean court system, and thus being an international tribunal independent from national control.[25] Nevertheless, it is considered as a “hybrid” tribunal since its jurisdiction extends over both domestic and international crimes and it relies on national authorities to enforce its orders. Still, in practice, there is no genuine cooperation between the government and the international community, as there is a limited extent of government participation in the Special Court’s process and the lack of consultation with the Sierra Leonean population before the Court’s endowment. This absence of national participation, despite causing scepticism over citizens, has the benefit that it remains more impartial when it comes to the proceedings against CDF leaders.

Another major particularity of the case of Sierra Leone and its process of implementation of transitional justice is once again the high degree of implication of children in the conflict, not only as victims but also as perpetrators of crimes. The responsibility of child soldiers for acts committed during armed conflict is a quite controversial issue. In general, under international law, the prosecution of children is not forbidden. However, there is no agreement on the minimum age at which children can be held criminally responsible for their acts. The Rome Statute, instituting the International Criminal Court (ICC), only provides the Court jurisdiction over people over eighteen years. Although not necessarily directly addressed to the prosecution of child soldiers, Article 40 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child foresees the trials of children (under eighteen), ordering that the process should consider their particular needs and vulnerabilities due to their shortage.

The TRC for Sierra Leone was the first one to focus on children's accountability, directly asserting jurisdiction over any person who committed a crime between the ages of fifteen and eighteen. Concerning child soldiers, the commission treated all children equally, as victims of war, but also studied the double role of children as both victims and perpetrators. It emphasized that it was not endeavouring to guilt but to comprehend how children came to carry out crimes, what motivated them, and how such offences might be prevented. Acknowledging that child soldiers are essentially victims of serious abuses of human rights and prioritizing the prosecution of those who illegally recruited them is of utmost importance. Meticulous attention was needed to guarantee that children’s engagement did not put them at risk or expose them to further harm. Proper safeguard and child-friendly procedures were ensured, such as special hearings, closed sessions, a safe and comfortable environment for interviews, preserving the identity of child witnesses, and psychological care, amongst others.

However, shall children that have committed war crimes be prosecuted in the first place? If not, is there a risk that tyrants may assign further slaughter to be performed by child soldiers due to the absence of responsibility they might possess? The lack of prosecution could immortalize impunity and pose a risk of alike violations reoccurring eventually, as attested by the re-recruitment of some child soldiers from Sierra Leone in other armed conflicts in the area, such as in Liberia. Considering the special conditions of child soldiers, it becomes clear that the RUF adult leaders primarily are the ones with the highest responsibility, and hence must be prosecuted.[26]

It is known that both the Sierra Leonean government and the RUF were involved in the recruitment of child soldiers as young as ten years old, which is considered a violation of both domestic and international humanitarian law. Under domestic law, in Sierra Leone, the minimum age for voluntary recruitment is eighteen years. International humanitarian law, (Additional Protocol II) fifteen is established as the minimum age qualification for recruitment (both voluntary or compulsory) or participation in hostilities (includes direct participation in combat and active participation linked to combat such as spying, acting as couriers, and sabotage.). Additionally, the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child[27] to which Sierra Leone is a signatory, requires “state parties . . . to take all necessary measures to ensure that no child below age eighteen shall take direct part in hostilities” and “to refrain in particular from recruiting any child.”

Nevertheless, victims who have been hurt by children also have the right to justice and reparations, and it also comes to ask whether exempting children of accountability for their crimes is in their best interest. When the child was in control of their actions (not coerced, drugged, or forced) acknowledgement might be an important part of personal healing that also adds to their acceptance back in their communities. The prosecution, however, should not be the first stage to hold child soldiers accountable, as TRC in Sierra Leone also performs alternatives, so the possibility of using those should first be inquired, as these alternatives put safeguards to ensure the best interest of the child and the main aim is restorative justice and not criminal prosecution.

Conclusions

Finally, after parsing where peacebuilding and justice clash and when do they have shared methods, we can assert that establishing an equitable and durable peace requires pursuing both peacebuilding and transitional justice activities, taking into consideration how they interact and the concrete needs of each community, especially when it comes to the needs of former child soldiers and the controversial debate around the need for their accountability and reinsertion in communities, as despite the pioneer case of Sierra Leone, the unusual condition of a child combatant, which is both victim and perpetrator still presents dilemmas concerning their accountability in international criminal law.[28]

Additionally, it becomes of utmost importance in assessing post-conflict societies, whether it is to implement peacebuilding measures such as DDR or to apply justice and search for accountability, that international led initiatives include in their program’s local organizations. Critics of international criminal justice often assume that criminal accountability for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes are better handled at the national level. While this may well hold for liberal democracies, it is far more problematic for post-conflict successor regimes, where the benefits of the proximity to the affected population must be seriously weighed against the challenges facing courts placed in conflict-ridden societies with weak and corrupt judiciaries.

Local systems however have more legitimacy and capacity than devastated formal systems, and they promise local ownership, access, and efficiency, which seems to be the most appropriate way to ensure peace and endurability of peace. Additionally, restorative justice methods put into place thanks to local initiatives emphasize face-to-face intervention, where offenders have the chance to ask for forgiveness from the victims. In many cases restitution replace incarceration, which facilitates the reintegration of offenders into society as well as the satisfaction of the victims.

To conclude, it has become clear that improving the interaction between peacebuilding and transitional justice processes requires coordination as well as a deep knowledge and understanding of said community. It is therefore not a question of deciding whether peacebuilding initiatives or transitional justice must be implemented, but rather to coordinate their efforts to achieve a sense of sustainable and most-needed peace in post-conflict countries. Taken together, and despite their contradictions, these processes are more likely to succeed in their seek to foster fair and enduring peace.

[1] Sooka, Y., 2006. Dealing with the past and transitional justice: building peace through accountability. [online] International Review of the Red Cross. https://www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/a21925.pdf [Accessed 5 April 2021].

2Boutros-Ghali, B. (1992). An Agenda for Peace:Preventive Diplomacy, Peacemaking and peace-keeping.Report of the Secretary-General UN: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/145749 [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[3]Brahimi. (s.f.). Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations. 55th Session: Brahimi Report | United Nations Peacekeeping [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[4] United Nations Secretary General (1992). "An Agenda for Peace, Preventive diplomacy, peacemaking and peace-keeping UN Doc. A/47/277 - S/24111, 17 June.", title VI, paragraph 55.<A_47_277.pdf (un.org)>. [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[5] Sooka, Y., 2006. Dealing with the past and transitional justice: building peace through accountability. [online] International Review of the Red Cross. Available at: < https://www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/a21925.pdf > [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[6] Roser, M. and Nagdy, M., 2021. Genocides. [online] Our World in Data. Available at: < Genocides - Our World in Data > [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[7] Waldorf, L., 2006. Mass Justice For Mass Atrocity: Rethinking Local Justice As Transitional Justice. [online] Temple Law Review. Available at: < https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/temple79&div=7 > [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[8] Gibril Sesay, M. and Suma, M., 2009. Transitional Justice and DDR: The Case of Sierra Leone. [online] International Center for Transitional Justice. Available at: < https://www.ictj.org/sites/default/files/ICTJ-DDR-Sierra-Leone-CaseStudy-2009-English.pdf > [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[9] Roht-Arriaza, N., & Mariezcurrena, J. (Eds.). (2006). Transitional Justice in the Twenty-First Century: Beyond Truth versus Justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chapter 2, Sigal HOROVITZ: Transitional criminal justice in Sierra Leone. <(PDF) Transitional Criminal Justice in Sierra Leone | Sigall Horovitz - Academia.edu >[Accessed 5 March 2021]

[10] Connolly, L., 2012. Justice and peacebuilding in postconflict situations: An argument for including gender analysis in a new post-conflict model. [online] ACCORD. Available at: < https://www.accord.org.za/publication/justice-peacebuilding-post-conflict-situations/ > [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[11] Waldorf, L., 2009. Transitional Justice and DDR: The Case of Rwanda. [online] Intenational Center for Transitional Justice. Available at: < https://www.ictj.org/sites/default/files/ICTJ-DDR-Rwanda-CaseStudy-2009-English.pdf >[Accessed 5 April 2021].

[13] UNICEF (2004). From Confict to Hope:Children in Sierra Leone’s Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration Programme. [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[14] SESAY, M.G & SUMA, M. (2009), “Transitional Justice and DDR: The Case of Sierra Leone”,International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[15] WILLIAMSON, J. (2006), “The disarmament, demobilization and reintegration of child soldiers: social and psychological transformation in Sierra Leone”, Intervention 2006, Vol. 4, No. 3, Available from: < http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.600.1127&rep=rep1&type=pdf> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[16] : A. B. Zack‐Williams (2001) Child soldiers in the civil war in Sierra Leone, Review of African Political Economy, 28:87, 73-82, DOI: 10.1080/03056240108704504 [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[17] MCKAY, S. & MAZURANA, D. (2004), “Where are the girls? Girls in Fighting Forces in Northern Uganda, Sierra Leone and Mozambique: Their Lives During and After War”,Rights & Democracy. International Centre for Human Rights & Democratic Development,.[Accessed 5 April 2021].

[18] UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) (2005), “The Impact of Conflict on Women and Girls in West and Central Africa and the Unicef Response”, Emergencies, pg.19,Available from: < https://www.unicef.org/emerg/files/Impact_conflict_women.pdf> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[19] Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers (2006), “Child Soldiers and Disarmament, Demobilization, Rehabilitation and Reintegration in West Africa”. [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[20] HRW (Human Rights Watch) (2005), “Problems in the Disarmament Programs in Sierra Leone and Liberia [1998-2005]”, Reports Section, Available from: <https://www.hrw.org/reports/2005/westafrica0405/7.htm> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[21] Herman, J., Martin-Ortega, O. and Sriram, C., 2012. Beyond justice versus peace: transitional justice and peacebuilding strategies. 1st ed. Routledge. <Beyond justice versus peace: transitional justice and peacebuilding strategies | Taylor & Francis Group> [Accessed 5 March 2021]

[22] Young, G., n.d. Transitional Justice in Sierra Leone: A Critical Analysis. [online] PEACE AND PROGRESS – THE UNITED NATIONS UNIVERSITY GRADUATE STUDENT JOURNAL. Available at: < https://postgraduate.ias.unu.edu/upp/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/upp_issue1-YOUNG.pdf > [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[23] Herman, J., Martin-Ortega, O. and Sriram, C., 2012. Beyond justice versus peace: transitional justice and peacebuilding strategies. 1st ed. Routledge. <Beyond justice versus peace: transitional justice and peacebuilding strategies | Taylor & Francis Group> [Accessed 5 March 2021]

[24] Stensrud, E., 2009. New Dilemmas in Transitional Justice: Lessons from the Mixed Courts in Sierra Leone and Cambodia. [online] Journal of peace research. Available at: <New Dilemmas in Transitional Justice: Lessons from the Mixed Courts in Sierra Leone and Cambodia on JSTOR> [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[25] Roht-Arriaza, N., & Mariezcurrena, J. (Eds.). (2006). Transitional Justice in the Twenty-First Century: Beyond Truth versus Justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chapter 2, Sigal HOROVITZ: Transitional criminal justice in Sierra Leone. <(PDF) Transitional Criminal Justice in Sierra Leone | Sigall Horovitz - Academia.edu >[Accessed 5 March 2021]

[26] Zarifis, Ismene. "Sierra Leone’s Search for Justice and Accountability of Child Soldiers." Human Rights Brief 9, no. 3 (2002): 18-21. [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[27] Article 22 of the AFRICAN CHARTER ON THE RIGHTS AND WELFARE OF THE CHILD , achpr_instr_charterchild_eng.pdf (un.org). [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[28] Veiga, T. G. (2019). A New Conceptualisation of Child Reintegration in Conflict Contexts. E International Relations: https://www.e-ir.info/2019/06/21/a-new-conceptualisation-of-child-reintegration-in-conflict-contexts/. [Accessed 5 April 2021].

Primer encuentro de alto nivel EEUU-China de la era Biden, celebrado en Alaska el 18 de marzo de 2021 [Dpto. de Estado]

ENSAYO / Ramón Barba

El presidente Joe Biden está construyendo con cautela su política para el Indo-Pacífico, buscando construir una alianza con India sobre la que construir un orden que contrarreste el auge chino. Tras su entrada en la Casa Blanca, Biden ha mantenido el foco de atención en esta región, aunque con un enfoque diferente al de la Administración Trump. Si bien es cierto que el objetivo principal sigue siendo contener a China y defender el libre comercio, Washington está optando por un acercamiento multilateral que otorga mayor protagonismo al QUAD[1] y cuida especialmente la relación con India. Como abanderada del mundo libre y de la democracia, la Administración Biden pretende renovar el liderazgo estadounidense en el mundo y particularmente en esta decisiva región. No obstante, aunque la relación con India se encuentra en un buen momento, especialmente teniendo en cuenta la firma del acuerdo BECA[2] alcanzado al final de la Administración Trump, la interacción entre ambos países está lejos de consolidar una alianza.

La nueva presidencia de Estados Unidos se encuentra con un puzle muy complicado de resolver en Indo-Pacífico, cuyos principales actores son China y la India. Por lo general, nos encontramos con que, de las tres potencias, solo Pekín ha sabido gestionar con éxito la situación post-pandemia[3], mientras que Delhi y Washington siguen enfrentando una crisis tanto sanitaria como económica. Todo ello puede afectar a la relación entre India y Estados Unidos, en especial en lo comercial[4], no obstante, y a pesar de que Biden aún no ha demostrado cuál va a ser su estrategia en la región, todo parece que la relación entre ambas potencias va a ir a más[5]. Sin embargo, a pesar de que Estados Unidos quiere llevar a cabo una política de alianzas multilateral y profundizar en su relación con la India, la Administración Biden deberá tener en cuenta diversas dificultades antes de poder hablar de una alianza como tal.

Biden comenzó a actuar en esta dirección desde el primer momento. En primer lugar estuvo en febrero la reunión del QUAD[6], que algunos consideran una mini OTAN[7] para Asia, en la que se discutieron cuestiones relativas a la distribución de la vacuna en Asia (pretendiendo distribuir un billón de dosis en 2022), la libertad de navegación en los mares de la región, la desnuclearización de Corea del Norte y la democracia en Myanmar. Además, el Reino Unido parece estar mostrando un interés mayor en la región y en este grupo de diálogo. Por otro lado, a mediados de marzo hubo una reunión en Alaska[8] entre las diplomacias de China y de Estados Unidos (encabezadas, respectivamente, por Yang Jiechi, director de la Comisión Central de Asuntos Exteriores, y Antony Blinken, secretario de Estado), en la cual ambos países se reprocharon duramente sus políticas. Washington se mantiene firme en sus intereses, aunque abierto a cierta colaboración con Pekín, mientras que China insiste en rechazar cualquier injerencia en lo que considera sus asuntos internos. Por último, cabe mencionar que Biden parece estar dispuesto a organizar una cumbre de democracias[9] en su primer año de mandato.

Tras los contactos que también hubo en Alaska entre los titulares de Defensa de China y de Estados Unidos, Austin Lloyd[10], jefe del Pentágono, visitó la India para remarcar la importancia de la cooperación indo-estadounidense. Además, a comienzos de abril se produjo la participación de Francia en las maniobras navales La Pérouse[11] en la Bahía de Bengala, dando lugar a la posibilidad de un QUAD-plus en el que, además de las cuatro potencias originales, se integren también otros países.

El Indo-Pacífico recordemos, se asienta como el presente y el futuro de las relaciones internacionales debido a su importancia económica (sus principales actores, India, China y EEUU representan el 45% del PIB mundial), demográfica (albergando un 65% de la población de todo el Globo) y, como veremos a lo largo del presente artículo, geopolítica[12].

Las relaciones entre EEUU, China e India

La Administración Biden parece ser continuista con la línea seguida por Trump, puesto que los objetivos no han variado. Lo que sí que cambia es el acercamiento hacia el objeto de la cuestión, que en este caso no es otro que la contención de China y la libertad de navegación en la región, ahora bien, en base a una gran apuesta por el multilateralismo. Como bien dijo el nuevo sucesor de George Washington en su toma de posesión[13], Estados Unidos quiere retomar su liderazgo, pero de una manera diferente a la de la Administración anterior; esto es, mediante una fuerte política de alianzas, un liderazgo moral y una fuerte defensa de valores como la dignidad, los derechos humanos y el Estado de Derecho.

La nueva presidencia concibe a China como un rival para tener en cuenta[14], al igual que la Administración Trump, pero no ve esto como un juego de suma cero, puesto que, aunque declara abiertamente estar en contra de la actuación de Xi, abre la puerta al diálogo[15] en materias como el cambio climático o la sanidad. Por lo general, en línea con lo visto en Nuevas tensiones en Asia Pacífico[16], Estados Unidos apuesta por un multilateralismo que busca rebajar la tensión. Recordemos que Estados Unidos propugna la defensa de la libre navegación y el Estado de Derecho, así como de la democracia en una región en la que está viendo mermada su influencia por el creciente peso de China.

Para entender bien el estado de las relaciones entre Estados Unidos, China e India cabe que remontarse a 2005[17], cuando todo parecía ir bien. En lo relativo a la relación sino-india, ambas naciones habían resuelto sus disputas motivo de los ensayos nucleares de 1998; además, su presencia en foros regionales era creciente y parecía que la cuestión relativa a las disputas transfronterizas comenzaba a arreglarse. Por su parte, Estados Unidos gozaba de buenas relaciones comerciales con ambos países. Sin embargo, el cambio de patrones en la economía mundial, motivado por el auge de China; la crisis financiera de 2008, surgida en Estados Unidos, y la inhabilidad de India para mantener la tasa de crecimiento rompieron este equilibrio. A ello contribuyó la actitud tirante de Donald Trump. No obstante, hay quien argumenta que la rotura del orden posterior a la Guerra Fría en Asia Pacífico comenzó con el “pivote hacia Asia”[18] de la Administración Obama. A ello hay que añadir los pequeños roces que China ha tenido con ambas naciones.

Brevemente, cabe mencionar que entre India y China existen problemas fronterizos[19] que a partir de 2013 se han ido reavivando. A su vez, India es contraria a la hegemonía china; no quiere verse subyugada por Pekín y apuesta claramente por el multilateralismo. Finalmente, existen problemas en lo relativo al dominio marítimo debido a que el Estrecho de Malaca está al límite de su capacidad. Además, Delhi reclama como suyas las islas Adaman y Nicobar, en la ruta de acceso a Malaca. Es más, como India ahora se encuentra muy por debajo del poder militar y económico de China[20] –roto el equilibrio que había entre las dos potencias en 1980–, intenta poner trabas a Pekín para así contenerle.

Estados Unidos mantiene roces de tipo ideológico con China, debido al carácter autoritario del régimen de Xi Jinping[21], y comercial, en una pugna[22] que Pekín pretende aprovechar para aminorar la influencia estadounidense en la zona. En medio de este conflicto está India, que apoya a Estados Unidos puesto que, aunque no parece querer estar del todo en contra de China[23], rechaza una hegemonía regional china[24].

Según el último informe del CEBR[25], China superará a Estados Unidos como potencia mundial en 2028, antes de lo previsto en proyecciones anteriores, en parte gracias a cómo ha gestionado la emergencia del coronavirus: ha sido el único gran país que tras la primera oleada ha evitado una crisis. Por otro lado, Estados Unidos ha perdido la batalla contra la pandemia; se espera que se crecimiento económico entre 2022-2024 sea del 1.9% del PIB y se reduzca al 1.6% en los siguientes ejercicios[26], mientras que China, según el informe estará entre 2021-2025 creciendo al 5.7%[27].

Para China la pandemia ha sido una forma de indicar su lugar en el mundo[28], una manera de avisar a Estados Unidos de que está lista para tomar el testigo como líder de la comunidad internacional. A ello cabe aunarle la actitud beligerante de China en la región de Asia Pacífico, así como su crecimiento hegemónico en la zona y proyectos comerciales con África y Europa. Todo ello ha llevado a desequilibrios en la región que implican los movimientos de Washington en lo relativo al QUAD. Recordemos que, a pesar de su rol menguante como potencia, a Estados Unidos le interesa la libertad de navegación por razones tanto comerciales como militares[29].

Así pues, el auge económico chino ha dado lugar a un empeoramiento de la relación entre Washington y Pekín[30]. Además, aunque Biden apuesta por la cooperación en lo relativo a la pandemia y al cambio climático, desde algunos sectores de la política americana se habla de una competición inevitable entre ambos países[31].

El grado de alianza entre EEUU e India

En línea con lo expuesto anteriormente podemos observar que nos movemos en tesituras delicadas, tras el cambio en la Casa Blanca. Enero y febrero han sido meses de pequeños movimientos por parte de Estados Unidos e India, que no han dejado indiferente a China. Aunque la relación chino-estadounidense ha beneficiado a ambas partes desde su inicio (1979)[32], creciendo el comercio entre ambos países en un 252% desde entonces, la realidad es que ahora los niveles de confianza están por los suelos, habiendo suspendido más de 100 mecanismos de diálogo entre ellos. Por lo tanto, aunque no se prevé un conflicto, sí que se pronostica un aumento de la tensión ya que, lejos de poder cooperar en amplios campos, por el momento solo parecen viables cooperaciones leves y limitadas. A su vez, recordemos que China se ve muy afectada por el Dilema de Malaca[33], por lo que busca otros accesos al Océano Índico, dando lugar a disputas territoriales con la India, con quien ya tiene el problema territorial de Ladakh[34]. En medio de esta Trampa de Tucídides[35], en la que China parece amenazar con superar a Estados Unidos, Washington se ha ido acercando a Nueva Delhi.

Por consiguiente, ambos países han ido desarrollando una colaboración estratégica[36], basada esencialmente en seguridad y defensa, pero que Estados Unidos busca ampliar a otras áreas. Bien es cierto que los problemas de Delhi están en el Índico y los de Washington en el Pacífico; sin embargo, ambos tienen a China[37] como denominador común. Su relación, además, se ve muy marcada por la ya expuesta “crisis tripartita”[38] (sanitaria, económica y geopolítica).

A pesar de la intensa cooperación entre Washington y Nueva Delhi, encontramos dos puntos de vista diferentes en lo relativo a este “partnership”. Mientras que desde Estados Unidos se afirma que India es un aliado muy importante, con el que comparte mismo sistema político y una intensa relación comercial[39], India prefiere una alianza menos estricta. Tradicionalmente, desde Delhi se ha transmitido una política de no alineamiento[40] en materias internacionales. De hecho, aunque India no quiere una supremacía China en el Indo-Pacífico, tampoco desea alinearse directamente contra Pekín, con quien comparte más de 3.000 km de frontera. No obstante, desde Delhi se ve muy necesaria la cooperación con Washington en materia de seguridad y defensa. De hecho, hay quien afirma que hoy la India necesita a EEUU más que nunca.

Si bien el pasado febrero, desde Washington se comenzó a revisar la Estrategia de Posición Global de Estados Unidos, todo apunta a que la Administración Biden continuará la línea de Trump en lo relativo a la colaboración con India como forma de contener a China. Sin embargo, aunque Washington habla de India como su aliado, por parte de Delhi hay ciertas reticencias, hablando pues de un alineamiento[41] más que de una alianza. Aunque la realidad que vivimos dista de la de la Guerra Fría[42], este nuevo containment[43] en el que se busca a Delhi como base, apoyo y estandarte, se ve materializado en lo siguiente:

i) Una intensa cooperación en materia de Seguridad y Defensa

Aquí existen distintos foros y acuerdos. En primer lugar, el ya mencionado QUAD[44]. Esta nueva alianza de cooperación multilateral que comenzó a gestarse en 2006[45] acordó en su reunión de marzo el desarrollo de su diplomacia de vacunas, con India como eje para así contrarrestar la exitosa campaña internacional llevada por Pekín en este campo. De hecho, hubo el compromiso de emplear 600 millones para repartir 1.000 millones de vacunas[46] en 2022. La idea es que Japón y EEUU financien la operación[47], mientras que Australia se encarga de la logística. No obstante, India apuesta por un mayor multilateralismo en el Indo-Pacífico, dando entrada a países como Inglaterra o Francia[48], que ya participaron en los últimos Diálogos de Raisina junto con el QUAD. A lo largo de la reunión también se trataron otros temas como la desnuclearización de Corea, la restauración democrática de Myanmar y el cambio climático[49].

India busca contener a China, pero sin provocar un enfrentamiento directo con China[50]. De hecho, Pekín ha dado a entender que de ir las cosas más allá, no solo India sabe jugar a la Realpolitk. Recordemos que Nueva Delhi va a presidir este año la reunión con los BRICS. Además, la Shanghai Cooperation Organization va a acoger ejercicios militares conjuntos de China y Pakistán, país de compleja relación con India.

Por otro lado, en su viaje de marzo a India, el jefe del Pentágono[51] trató con su homólogo Rajnath Singh sobre el incremento de la cooperación militar, así como de asuntos relacionados con la logística, el intercambio de información, posibles oportunidades de asistencia mutua y la defensa de la libre navegación. Lloyd afirmó no ver con malos ojos que Australia y Corea participen como miembros permanentes en los ejercicios Malabar. Desde 2008 el comercio en materia militar entre Delhi y Washington suma 21 billones de dólares[52]. Además, recientemente, se han gastado 3000 de dólares en drones y otro material aéreo para misiones de reconocimiento y vigilancia.

Una semana después esta reunión, dos barcos indios y uno estadounidense realizaron un ejercicio marítimo de tipo PASSEX[53] como forma de consolidar las sinergias e interoperabilidad alcanzadas en el ejercicio de Malabar del pasado noviembre.

En este contexto, cabe hacer una mención especial a la plataforma de diálogo 2+2 y al ya mencionado BECA (Acuerdo Básico de Intercambio y Cooperación para la cooperación en materia geoespacial). El primero, es un tipo de reunión en la que los titulares de Exteriores y Defensa de ambos países se reúnen cada dos años para tratar de temas que les sean de interés. La reunión más reciente tuvo lugar en octubre de 2020[54]. En ella no solo se acordó el BECA, sino que Estados Unidos se reafirmó en su apoyo a India en lo relativo a sus problemas territoriales con China. A su vez, también se firmaron otros memorándums de entendimiento sobre cuestiones de energía nuclear y climáticas.

El BECA, firmado en octubre de 2020 durante los últimos meses de la Administración Trump, facilita a India localizar mejor a enemigos, terroristas y otro tipo de amenazas que vengan desde tierra o desde mar. Con este acuerdo se pretende consolidar la amistad que hay entre ambos países, así como ayudar a India a superar tecnológicamente a China. En virtud de este acuerdo se concluye la “troika de pactos fundacionales” para una profunda cooperación en seguridad y defensa entre ambos países[55].

Antes de este acuerdo, en 2016 se firmó el LEMOA (Memorando de Acuerdo para el Intercambio de Logística), y en 2018 el COMCASA (Acuerdo de Compatibilidad y Seguridad de las Comunicaciones). El primero permite a ambos países acceso a las bases de cada uno para abastecimiento y reposición; el segundo permite a India recibir sistemas, información y comunicación encriptada para comunicarse con Estados Unidos. Ambos acuerdos afectan a los ejércitos de tierra, mar y aire[56].

ii) Unidos por la democracia

Desde Washington se pone especial énfasis en que ambas potencias son muy semejantes, puesto que comparten el mismo sistema político, y se destaca con cierta grandilocuencia que conforman la democracia más antigua y la más grande (por número de habitantes)[57]. Debido a que eso presupone compartir una serie de valores, Washington gusta hablar de “likeminded partners”[58].

Desde el think tank Brookings Institution, Tanvi Mandan defiende esta idea de ligazón ideológica. El mismo sistema de gobierno hace que ambos países se vean como aliados naturales, que piensan igual y que además creen en el valor del imperio de la ley. De hecho, en todo lo relativo a la extensión de la democracia por el globo, hay una fuerte cooperación entre ambas naciones: por ejemplo, apoyando la democracia en Afganistán o en Maldivas, lanzando la US-India Global Democracy Iniciative y dotando de asistencia legal y técnica en cuestiones democráticas a otros países. Finalmente cabe resaltar que la democracia y los valores que acarrea han facilitado el intercambio y flujo de personas de un país a otro. En cuanto a la relación económica entre ambos países se vuelve más viable, puesto que los dos son economías abiertas, comparten una lengua y su sistema jurídico tiene raigambre anglosajona.

iii) Creciente cooperación económica

Estados Unidos es el principal socio comercial de India, con quien tiene un importante superávit[59]. Los intercambios entre ambos han crecido un 10% anual a lo largo de la última década, y en 2019 fueron de 115.000 millones de dólares[60]. Alrededor de 2.000 empresas estadounidenses están instaladas en India, y unas 200 empresas indias se hallan en EEUU[61]. Entre ambos existe un Mini-Trade Deal, que se cree que será firmado en breve, y que tiene por objeto ahondar en esta relación económica. Con motivo de la pandemia, todo lo relativo al ámbito sanitario tiene un papel importante[62]. De hecho, a pesar de que ambos países han adoptado recientemente una actitud proteccionista, la idea es alcanzar 500.000 millones de dólares en comercio[63].

Divergencias, retos y oportunidades para India y EEUU en la región

Brevemente, entre los líderes de ambos países hay pequeños roces, oportunidades y retos a matizar para hacer de esta relación una fuerte alianza. Dentro de los puntos de conflicto, destacamos la compra desde India de misiles S-400 a Rusia, lo cual va en contra del CAATSA (Countering America’s Adversaries trhough Sanctions Act) [64], por lo que puede que India reciba una sanción, aunque en la reunión entre Sigh y Lloyd, este pareció pasar el tema por alto[65]. Sin embargo, cabe ver qué pasa una vez lleguen los misiles a Delhi. También existen pequeñas divergencias en lo relativo a libertad de expresión, seguridad y derechos civiles, y cómo relacionarse con países no democráticos[66]. Dentro de los retos que ambos países deben tener en cuenta, está la posible pérdida de apoyo en algunos sectores de la política estadounidense a la relación con India. Ello se debe a las actuaciones de India en Cachemira en agosto de 2019, la protección de la libertad religiosa y el trato a la disidencia. Por otro lado, en el caso contrario no ha faltado el debilitamiento de las normas democráticas, restricciones a la inmigración y violencia contra naturales de India[67].

En último lugar, recordemos que ambos se enfrentan a una profunda crisis sanitaria y por consiguiente económica, cuya resolución será determinante en relación con la competición con Pekín[68]. La crisis ha afectado a la relación bilateral puesto que, aunque el comercio en servicios se ha mantenido estable (alrededor de los 50.000 millones), el comercio de bienes decayó de 92.000 a 78.000 millones entre 2019 y 2020, aumentando el déficit comercial indio[69].

Para finalizar, cabe mencionar las oportunidades. En primer lugar, ambos países pueden desarrollar resiliencia democrática en el Indo-Pacífico así como en un orden internacional basado en normas[70]. En seguridad y defensa, también hay oportunidades como la entrada de Reino Unido y Francia como aliados en la zona, por ejemplo intentando que ambos países entren en el ejercicio de Malabar o que Francia presida el Indian Ocean Naval Simposium de 2022[71]. Aunque la tendencia a medio plazo es de cooperación entre Estados Unidos e India, la competencia con Rusia será una amenaza creciente[72], por lo que la cooperación entre Estados Unidos, India y Europa es muy importante.

También se abre la posibilidad de cooperación en mecanismos de MDA (Alerta del Entorno Marítimo) y ASW (Guerra Anti Submarina), en tanto que el Océano Índico reviste una importancia general para varios países debido al valor de sus rutas de transporte energético. Se abre la posibilidad de la cooperación mediante el uso de la Aeronave US P-8 “Poseidón”. A pesar de las disputas sobre el archipiélago de Chagos, India y Estados Unidos deberían aprovechar los acuerdos que tienen sobre islas como Andamán o Diego García para la realización de estas actividades[73]. Por lo tanto, India debería usar los organismos y grupos de trabajo regionales para cooperar con los países europeos y Estados Unidos[74].

Europa parece adquirir una creciente importancia debido a la posibilidad de entrar en el juego del Indo-Pacífico mediante el QUAD Plus. Los países europeos están muy a favor del multilateralismo, de la defensa de la libertad de navegación y del papel de las normas para regularla. Si bien es cierto que la UE ha firmado recientemente un tratado de comercio con China recientemente -el CAI-, incrementar la presencia europea en la región adquiere mayor importancia, puesto que el autoritarismo de Xi y sus actuaciones en Tíbet, Xinjiang, o el centro de China no son plato de buen gusto para los países europeos[75].

En último lugar, cabe recordar que hay algunas voces que hablan de un decaimiento o debilitamiento de la globalización[76], en especial tras la epidemia del coronavirus[77], por lo cual reavivar los intercambios multilaterales mediante la acción conjunta se convierte en un reto y en una oportunidad para ambos países. De hecho, se cree que a corto plazo las tendencias proteccionistas, al menos en el ámbito de la relación sino-india van a continuar, a pesar de la intensa cooperación económica[78].

Conclusión

El panorama geopolítico del Indo-Pacifico es cuanto menos complejo. El expansionismo chino choca con los intereses de la otra gran potencia regional, India, que si bien evita enfrentarse a Pekín ve con malos ojos la actuación de su vecino. En una apuesta por el multilateralismo, y con la mirada puesta en sus aguas regionales, amenazadas por el Dilema de Malaca, la India parece cooperar con Estados Unidos, pero aferrándose a los foros y grupos regionales para dejar clara su postura, mientras parece abrir la puerta a los países europeos, cuyo interés en la región va en aumento, a pesar del reciente tratado comercial firmado con China.

Por otro lado, también Estados Unidos se ve amenazado por el expansionismo chino y ve acercarse el momento del sorpasso económico de su rival, que la crisis del coronavirus pude haber adelantado incluso a 2028. En aras de evitar tal situación, la Administración Biden apuesta por el multilateralismo a nivel regional y ahonda en su relación con India, más allá de lo militar. Desde Washington parece haberse entendido que la hegemonía estadounidense en el Indo-Pacífico dista de ser real, al menos a medio plazo, por lo que solo cabe una actitud cooperativa e integradora. Por otro lado, en medio de este supuesto repliegue de la globalización, vemos cómo Washington junto con la India, y seguramente a medio plazo con Europa, hacen defensa de los valores occidentales que rigen en la esfera internacional, esto es, defensa de los derechos humanos, del estado de derecho y del valor de la democracia.

Estamos ante dos factores. Por un lado, India no quiere ver cómo se impone un orden de ningún tipo, ni americano ni chino, de ahí sus reticencias a enfrentarse directamente contra Pekín y su preferencia a expandir el QUAD. Por otro lado, Estados Unidos parece percibir encontrarse en un momento delicado, puesto que su competición con China va más allá de la mera sustitución de una potencia por otra. Washington no deja de ser una potencia tradicional que, para su presencia en el Indo-Pacífico, se ha servido sobre todo de poder militar, mientras que China ha basado la extensión de su influencia en el establecimiento de fuertes relaciones comerciales que van más allá de la lógica beligerante de la Guerra Fría. De ahí que Estados Unidos intente formar un frente con India y sus aliados europeos, que además vaya más allá de la cooperación militar.

REFERENCIAS

[1] El QUAD (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue), es un grupo de diálogo formado por los Estados Unidos, India, Japón y Australia. Sus miembros comparten una visión común sobre la seguridad de la región Indo-Pacífico contraria a la de China; abogan por el multilateralismo y la libertad de navegación en la región.

[2] BECA (Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement). Tratado firmado por la India y Estados Unidos en octubre de 2019 para mejorar la seguridad en la región del Indo-Pacífico. Su objetivo es el intercambio de sistemas de seguimiento, localización e inteligencia.

[3]Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, "Trilateral Perspective". Chinawatch. Conecting Thinkers.. http://www.chinawatch.cn/a/202102/05/WS60349146a310acc46eb43e2d.html, (accedido el 5 de febrero de 2021),

[4] Tanvi Madan,”India and the Biden Administration: Consolidating and Rebalancing Ties,” en Tanvi Madan, “India And The Biden Administration: Consolidating And Rebalancing Ties”,. German Marshal Found of the United States. https://www.gmfus.org/blog/2021/02/11/india-and-biden-administration-consolidating-and-rebalancing-ties, (accedido el 11 de febrero de 2021).