Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Entradas con Categorías Global Affairs Orden mundial, diplomacia y gobernanza .

Iran Strategic Report (July 2019)

This report will provide an in-depth analysis of Iran's role in the Middle East and its impact on the regional power balance. Studying current political and economic developments will assist in the elaboration of multiple scenarios that aim to help understand the context surrounding our subject.

J. Hodek, M. Panadero.

Report [pdf. 15,5MB]

Report [pdf. 15,5MB]

INTRODUCTION: IRAN IN THE MIDDLE EAST

This report will examine Iran's geopolitical presence and interests in the region, economic vulnerability and energy security, social and demographic aspects and internal political dynamics. These directly or indirectly affect the evolution of various international strategic issues such as the future of Iran's Nuclear Deal, United States' relations with Iran and its role in Middle East going forward. Possible power equilibrium shifts, which due to the economic and strategic importance of this particular region, possess high relevance and significant degree of impact even outside of the Iranian territory with potential alteration of the regional and international order.

With the aim of presenting a more long-lasting report, several analytical techniques will be used (mainly SWOT analysis and elaboration of simple scenarios), in order to design a strategic analysis of Iran in respect to the regional power balance and the developments of the before mentioned international strategic issues. Key geopolitical data will be collected as of the announcement of the U.S. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo on the re-imposition of U.S. sanctions on the Islamic Republic of Iran on November 2, 2018 with a projection for the upcoming years, thus avoiding a simple narration of facts, which transpired so far.

First part of this report will be dedicated to a more general analysis of the geopolitical situation in the Middle East, with a closer attention to Iran's interests and influence. Then, after a closer look on the internal dynamics within Iran, several scenarios will be offered out of which some will be categorized and selected as the most probable according to the authors of this report.

From Iranian strategic perspective the Sunni-Shi‘a divide is only part of its larger objective of exporting its revolution.

![Escena militar de un altorrelieve de la antigua Persia [Pixabay] Escena militar de un altorrelieve de la antigua Persia [Pixabay]](/documents/10174/16849987/ancient-iran-blog.jpg)

▲ Escena militar de un altorrelieve de la antigua Persia [Pixabay]

ESSAY / Helena Pompeya

At a first glance it may seem that the most important factor shaping the dynamics in the region is the Sunni-Shi’a divide materialized in the struggle between Saudi Arabia and Iran over becoming the main hegemonic power in the region. Nonetheless, from the strategic perspective of Iran this divide is only part of its larger objective of exporting its revolution.

This short essay will analyze three paths of action or policies Iran has been relying on in order to exert and expand its influence in the MENA region: i) it’s anti-imperialistic foreign policy; ii) the Sunni-Shi’a divide; and iii) opportunism. Finally, a study case of Syria will be provided to show how Iran made use of these three courses of action to its benefit within the war.

I. ANTI IMPERIALISM

The Sunni-Shi'a division alone would not be enough to rocket Iran into an advantaged position over Saudi Arabia, being the Shi’ites only a 13% of the total of Muslims over the world (found mainly in Iran, Pakistan, India and Iraq).[1] Even though religious affiliation can gain support of a fairly big share of the population, Iran is playing its cards along the lines of its revolutionary ideology, which consists on challenging the current international world order and particularly what Iran calls US’s imperialism.

Iran does not choose its strategic allies by religious affiliation but by ideological affinity: opposition to the US and Israel. Proof of this is the fact that Iran has provided military and financial support to Hamas and the Islamic Jihad in Palestine, both of them Sunni, in their struggle versus Israel.[2] Iran’s competition against Saudi Arabia could be understood as an elongation of its anti-US foreign policy, being the Saudi kingdom the other great ally of the West in the MENA region along with Israel.

II. SUNNI-SHI’A DIVIDE

Despite the religious divide not being the main reason behind the hegemonic competition among both regional powers Saudi Arabia (Sunni) and Iran (Shi’a), both states are exploiting this narrative to transcend territorial barriers and exert their influence in neighbouring countries. This rivalry materializes itself along two main paths of action: i) development of neopatrimonial and clientelistic networks, as it shows in Lebanon and Bahrain[3]; ii) and in violent proxy wars, namely Yemen and Syria.

a. Lebanon

Sectarian difference has been an inherent characteristic of Lebanon all throughout its history, finally erupting into a civil war in 1975. The Taif accords, which put an end to the strife attempted to create a power-sharing agreement that gave each group a political voice. These differences were incorporated into the political dynamics and development of blocs which are not necessarily loyal to the Lebanese state alone.

Regional dynamics of the Middle East are characterised by the blurred limits between internal and external, this reflects in the case of Lebanon, whose blocs provide space for other actors to penetrate the Lebanese political sphere. This is the case of Iran through the Shi‘ite political and paramilitary organization of Hezbollah. This organization was created in 1982 as a response to Israeli intervention and has been trained, organized and provisioned by Iran ever since. Through the empowerment of Iran and its political support for Shi’a groups across Lebanon, Hezbollah has emerged as a regional power.

Once aware of the increasing Iranian influence in the region, Saudi Arabia stepped into it to counterbalance the Shi’a empowerment by supporting a range of Salafi groups across the country.

Both Riyadh and Tehran have thus established clientelistic networks through political and economic support which feed upon sectarian segmentation, furthering factionalism. Economic inflows in order to influence the region have helped developed the area between Ras Beirut and Ain al Mraiseh through investments by Riyadh, whilst Iranian economic aid has been allocated in the Dahiyeh and southern region of the country.[4]

b. Bahrain

Bahrain is also a hot spot in the fight for supremacy over the region, although it seems that Saudi Arabia is the leading power over this island of the Persian Gulf. The state is a constitutional monarchy headed by the King, Shaikh Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa, of the Sunni branch of Islam, and it is connected to Saudi Arabia by the King Fahd Causeway, a passage designed and built to prevent Iranian expansionism after the revolution. Albeit being ruled by Sunni elite, the majority of the country’s citizens are Shia, and have in many cases complaint about political and economical repression. In 2011 protests erupted in Bahrain led by the Shi’a community, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates stepped in to suppress the revolt. Nonetheless, no links between Iran and the ignition of this manifestation have been found, despite accusations by the previously mentioned Sunni states.

The opposition of both hegemonic powers has ultimately materialized itself in the involvement on proxy wars as are the examples of Syria, Yemen, Iraq and possibly in the future Afghanistan.

c. Yemen

Yemen, in the southeast of the Arabian Peninsula, is a failed state in which a proxy war fueled mainly by the interests of Saudi Arabia and Iran is taking place since the 25th of March 2015. On that date, Saudi Arabia leading an Arab coalition against the Houthis bombarded Yemen.

The ignition of the conflict began in November 2011 when President Ali Abdullah Saleh was forced to hand over his power to his deputy and current president Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi (both Sunni) due to the uprisings product of the Arab Spring.[5]

The turmoil within the nation, including here al-Qaeda attacks, a separatist rising in the south, divided loyalties in the military, corruption, unemployment and lack of food, led to a coup d’état in January 2015 led by Houthi rebels. The Houthis, Shi‘ite Muslims backed by Iran, seized control of a large territory in Yemen including here the capital Sana’a. A coalition led by Saudi Arabia and other Sunni-majority nations are supporting the government.

Yemen is a clear representation of dispute over regional sovereignty. This particular conflict puts the Wahhabi kingdom in great distress as it is happening right at its front door. Thus, Saudi interests in the region consist on avoiding a Shi’ite state in the Arabian Peninsula as well as facilitating a kindred government to retrieve its function as state. Controlling Yemen guarantees Saudi Arabia’s influence over the Gulf of Aden and the Strait of Baab al Mandeb, thus avoiding Hormuz Strait, which is currently under Iran’s reach.

On the other hand, Iran is soon to be freed from intensive intervention in the Syrian war, and thus it could send in more military and economic support into the region. Establishing a Shi’ite government in Yemen would pose an inflexion point in regional dynamics, reinforcing Iran’s power and becoming a direct threat to Arabia Saudi right at its frontier. Nonetheless, Hadi’s government is internationally recognized and the Sunni struggle is currently gaining support from the UK and the US.

III. OPPORTUNISM

The Golf Cooperation Council (GCC) is a political and economic alliance of six countries in the Arabian Peninsula which fail to have an aligned strategy for the region and could be roughly divided into two main groups in the face of political interests: i) those more aligned to Saudi Arabia, namely Bahrain and UAE; ii) and those who reject the full integration, being these Oman, Kuwait and Qatar.

Fragmentation within the GCC has provided Iran with an opportunity to buffer against calls for its economic and political isolation. Iran’s ties to smaller Gulf countries have provided Tehran with limited economic, political and strategic opportunities for diversification that have simultaneously helped to buffer against sanctions and to weaken Riyadh.[6]

a. Oman

Oman in overall terms has a foreign policy of good relations with all of its neighbours. Furthermore, it has long resisted pressure to align its Iran policies with those of Saudi Arabia. Among its policies, it refused the idea of a GCC union and a single currency for the region introduced by the Saudi kingdom. Furthermore, in 2017 with the Qatar crisis, it opposed the marginalization of Qatar by Saudi Arabia and the UAE and stood as the only State which did not cut relations with Iran.

Furthermore, the war in Yemen is spreading along Oman’s border, and it’s in its best interest to bring Saudi Arabia and the Houthis into talks, believing that engagement with the later is necessary to put an end to the conflict.[7] Oman has denied transport of military equipment to Yemeni Houthis through its territory.[8]

b. Kuwait

A key aspect of Kuwait’s regional policy is its active role in trying to balance and reduce regional sectarian tensions, and has often been a bridge for mediation among countries, leading the mediation effort in January 2017 to promote dialogue and cooperation between Iran and the Gulf states that was well received in Tehran.[9]

c. Qatar

It has always been in both state’s interest to maintain a good relationship due to their proximity and shared ownership of the North/South Pars natural gas field. Despite having opposing interests in some areas as are the case of Syria (Qatar supports the opposition), and Qatar’s attempts to drive Hamas away from Tehran. In 2017 Qatar suffered a blockade by the GCC countries due to its support for Islamist groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood and militant groups linked to al-Qaeda or ISIS. During this crisis, Iran proved a good ally into which to turn.. Iran offered Qatar to use its airspace and supplied food to prevent any shortages resulting from the blockade.[10] However as it can be deduced from previous ambitious foreign policies, Qatar seeks to diversify its allies in order to protect its interests, so it would not rely solely on Iran.

Iran is well aware of the intra-Arab tensions among the Gulf States and takes advantage of these convenient openings to bolster its regional position, bringing itself out of its isolationism through the establishment of bilateral relations with smaller GCC states, especially since the outbreak of the Qatar crisis in 2017.

IV. SYRIA

Iran is increasingly standing out as a regional winner in the Syrian conflict. This necessarily creates unrest both for Israel and Saudi Arabia, especially after the withdrawal of US troops from Syria. The drawdown of the US has also originated a vacuum of power which is currently being fought over by the supporters of al-Assad: Iran, Turkey and Russia.

Despite the crisis involving the incident with the Israeli F-16 jets, Jerusalem is attempting to convince the Russian Federation not to leave Syria completely under the sphere of Iranian influence.

Israel initially intervened in the war in face of increasing presence of Hezbollah in the region, especially in its positions near the Golan Heights, Kiswah and Hafa. Anti-Zionism is one of Iran’s main objectives in its foreign policy, thus it is likely that tensions between Hezbollah and Israel will escalate leading to open missile conflict. Nonetheless, an open war for territory is unlikely to happen, since this will bring the UyS back in the region in defense for Israel, and Saudi Arabia would make use of this opportunity to wipe off Hezbollah.

On other matters, the axis joining Iran, Russia and Turkey is strengthening, while they gain control over the de-escalation zones.

Both Iran and Russia have economic interests in the region. Before the outbreak of the war, Syria was one of the top exporting countries of phosphates, and in all likelihood, current reserves (estimated on over 2 billion tons) will be spoils of war for al-Assad’s allies.[11]

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps took control of Palmira in 2015, where the largest production area of phosphates is present. Furthermore, Syria also signed an agreement on phosphates with Russia.

Iran has great plans for Syria as its zone of influence, and is planning to establish a seaport in the Mediterranean through which to export its petroleum by a pipeline crossing through Iraq and Syria, both under its tutelage[12]. This pipeline would secure the Shi’ite bow from Tehran to Beirut, thus debilitating Saudi Arabia’s position in the region. Furthermore, it would allow direct oil exports to Europe.

In relation to Russia and Turkey, despite starting in opposite bands they are now siding together. Turkey is particularly interested in avoiding a Kurdish independent state in the region, this necessarily positions the former ottoman empire against the U.S a key supporter of the Kurdish people due to their success on debilitating the Islamic State. Russia will make use of this distancing to its own benefits. It is in Russia’s interest to have Turkey as an ally in Syria in order to break NATO’s Middle East strategy and have a strong army operating in Syrian territory, thus reducing its own engagement and military cost.[13]

Despite things being in favour of Iran, Saudi Arabia could still take advantage of recent developments of the conflict to damage Iran’s internal stability.

Ethnic and sectarian segmentation are also part of Iran’s fabric, and the Government’s repression against minorities within the territory –namely Kurds, Arabs and Baluchis- have caused insurgencies before. Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States aligned with its foreign policy, such as the UAE are likely to exploit resentment of the minorities in order to destabilized Iran’s internal politics.

The problem does not end there for Iran. Although ISIS being wiped off the Syrian territory, after falling its last citadel in Baguz[14], this is not the end of the terrorist group. Iran’s active role in fighting Sunni jihadists through Hezbollah and Shi’ite militias in Syria and Iraq has given Islamist organization a motivation to defy Tehran.

Returning foreign fighters could scatter over the region creating cells and even cooperating with Sunni separatist movements in Ahwaz, Kurdistan or Baluchistan. Saudi Arabia is well aware of this and could exploit the Wahhabi narrative and exert Sunni influence in the region through a behind-the-scenes financing of these groups.

[1] Mapping the Global Muslim Population, Pew Research Center, 2009

[2] El derrumbe del Status Quo en OM: Las estrategias de seguridad de Irán y AS, David Poza Cano, enero 2017.

[3] Saudi Arabia, Iran and the Struggle for Supremacy in Lebanon and Bahrain, Simon Mabon, LSE 2018

[4] Ídem.

[5] Proxy war: What is the Yemen War about, is there a famine, why is Saudi Arabia involved and how many people have died? Guy Birchall, November 2018.

[6] Iran and the GCC Hedging, Pragmatism and Opportunism, Sanam Vakil, September 2018

[7] Reuters ‘Yemen’s Houthis and Saudi Arabia in secret talks to end war’, 15 March, 2018

[8] Bayoumy, Y. (2016), ‘Iran steps up weapons supply to Yemen’s Houthis via Oman’, Reuters, 30 October.

[9] Coates Ulrichsen, K., ‘Walking the tightrope: Kuwait, Iran relations in the aftermath of the Abdali affair’, Gulf States Analytics, 9 August, 2017

[10] Kamrava, M. ‘Iran-Qatar Relations’, in Bahgat, Ehteshami and Quilliam (2017), Security and Bilateral Issues Between Iran and Its Neighbours.

[11] The current situation in Syria, Giancarlo Elia Valori, Modern Diplomacy, January 2019

[12] Irán en la era de la administración Trump, Beatriz Yubero Parro, IEEE, 2017

[13] The current situation in Syria, Giancarlo Elia Valori, Modern Diplomacy, January 2019

[14] Confirman en Siria la derrota total del grupo terrorista ISIS, Clarín Mundo. 23 de marzo, 2019

La necesidad de mano de obra ha llevado tradicionalmente a Suecia a acoger olas de inmigrantes; sectores de la sociedad lo viven hoy como un problema

![Puente de Oresund, entre Dinamarca y Suecia, visto desde territorio sueco [Wikipedia] Puente de Oresund, entre Dinamarca y Suecia, visto desde territorio sueco [Wikipedia]](/documents/10174/16849987/suecia-migracion-blog.jpg)

▲ Puente de Oresund, entre Dinamarca y Suecia, visto desde territorio sueco [Wikipedia]

ANÁLISIS / Jokin de Carlos

Suecia ha tenido la reputación, desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial, de ser un país abierto a los inmigrantes y de desarrollar políticas sociales tolerantes y abiertas. Sin embargo, el aumento del número de inmigrantes, la lenta adaptación cultural de algunas de esas nuevas comunidades, especialmente la musulmana, y los problemas de violencia generados en áreas de mayor vulnerabilidad han provocado un intenso debate en la sociedad sueca. La opinión de que una generosa política migratoria puede estar destruyendo la identidad sueca y haciendo la vida más difícil para los suecos nativos ha alimentado el voto de cierta oposición de derechas, si bien los socialdemócratas revalidaron el año pasado el apoyo ciudadano para un Gobierno que mantiene las políticas tradicionales con cierto mayor énfasis en la expulsión de aquellos cuya solicitud ha sido rechazada.

Política migratoria

Uno de los problemas históricos de Suecia ha sido su baja tasa de fecundidad, que alrededor de la década de 1960 había ya caído al umbral de 2,1 hijos por mujer necesarios para el reemplazo poblacional. Eso era algo que amenazaba el célebre estado de bienestar sueco, por la necesidad de ingresos por impuestos que mantuvieran los generosos servicios públicos, de forma que el país promovió la llegada de inmigrantes. Al mismo tiempo, la necesidad de mano de obra también era planteada por el desarrollo de la industria nacional.

Suecia surgió de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en buenas condiciones. No sufrió la destrucción de otras naciones, al quedar territorialmente en los márgenes del conflicto, y pudo consolidar una industria metalúrgica que, gracias a la producción de sus minas de hierro, se había beneficiado de vender a los dos bandos en guerra. Ese desarrollo industrial requería de una gran fuerza de trabajo que la baja natalidad propia y la concentración de la población en la costa y en el sur, fuera de los núcleos industriales, dificultaban reunir. Además, el estado de bienestar sueco y las continuas décadas de paz crearon una clase media que no quería trabajar en la nueva industria por los bajos salarios que esta ofrecía para resultar competitiva.

Para resolver la falta de mano de obra y así mantener el progreso económico, desde la década de 1950 Suecia recurrió a la inmigración. El Gobierno abrió primero la frontera a quienes buscaban asilo o trabajo y luego construyó grupos de viviendas, generalmente de baja calidad, cerca de las áreas industriales donde los recién llegados podían encontrar empleos sin ningún requisito de idioma. Cuando el impacto cultural de esas incorporaciones era demasiado grande en algunas áreas, el Gobierno procedía a cerrar las fronteras, restringiendo la inmigración. Cuando se necesitaran nuevos trabajadores, el Gobierno volvía a abrir la frontera.

Este sistema ayudó a un importante avance económico, pero también aisló a muchos grupos sociales, que se quedaron estancados en áreas de bajos ingresos sin apenas posibilidad de desarrollo ni integración social.

Desarrollo histórico

Tanto durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial como a su término, Suecia fue un destino importante para personas procedentes de Noruega, Dinamarca, Polonia, Finlandia y las Repúblicas Bálticas que escapaban de la guerra o de la destrucción que creó; también fue un destino neutral para muchos judíos. En 1944, había en Suecia más de 40.000 refugiados; si bien muchos regresaron a sus países tras la contienda, un grupo considerable de ellos se quedó, principalmente estonios, letones y lituanos, cuyas naciones de origen fueron incorporadas a la URSS.

En 1952, Suecia, Dinamarca y Noruega formaron el Consejo Nórdico, creando un área de libre comercio y libertad de movimiento, a la que Finlandia se unió en 1955. Con esto, miles de migrantes fueron a Suecia para trabajar en la industria, principalmente de Finlandia pero también de Noruega, que aún no había descubierto sus reservas de petróleo. Esto aumentó el porcentaje de la población inmigrante del 2% en 1945 al 7% en 1970. Todo esto ayudó a Tage Erlander (primer ministro de Suecia entre 1946 y 1969) a crear el proyecto "Sociedad Fuerte", dirigido a aumento del sector público y el estado del bienestar. Sin embargo, este flujo de mano de obra comenzó a dañar a los trabajadores suecos nativos y, en consecuencia, en 1967, los sindicatos comenzaron a presionar a Erlander para que limitara la inmigración laboral a los países nórdicos.

En 1969, Erlander renunció al cargo y fue sustituido por su protegido, Olof Palme. Palme era miembro del sector más radical de los socialdemócratas y quería aumentar aún más el estado de bienestar, continuando el proyecto de su predecesor a una mayor escala.

Con el fin de atraer una fuerza laboral más grande sin enojar a los sindicatos, Palme comenzó a utilizar la retórica a favor de los refugiados, abriendo las fronteras de Suecia a las personas que escapaban de las dictaduras y la guerra. Al mismo tiempo, estas personas serían trasladadas a vecindarios industriales, construidos especialmente para ellos en áreas industriales cercanas donde trabajarían. Al mismo tiempo, Palme trató de hacer de Suecia un país atractivo para los inmigrantes mediante políticas de asimilación a favor del multiculturalismo.

Durante este período, personas de muchas nacionalidades comenzaron a llegar al país: desde quienes escapaban del conflicto en Yugoslavia o la ley marcial en Polonia a quienes huían de Oriente Medio y América Latina. Estas nuevas poblaciones se establecieron lejos de núcleos demográficos nativos suecos; debido a esto muchos vecindarios de la clase trabajadora se convirtieron en guetos aislados. En 1986, Palme fue asesinado y su sucesor, Ingvar Carlsson, cambió la política de inmigración y comenzó a aceptar solo a aquellos que configuraran como refugiados de acuerdo con las normas de las Naciones Unidas.

Durante la década de 1990, el aumento de los conflictos en lugares como Somalia, Yugoslavia y varias naciones africanas hizo aumentar el flujo de refugiados de guerra, y muchos de ellos fueron a Suecia. En 1996 se creó el Ministerio de Migración y Política de Asilo. Sin embargo, los dos mayores movimientos de personas de países extranjeros se producirían a raíz de los siguientes conflictos de Irak e Siria. El gobierno conservador de Fredrik Reinfeldt comenzó a acoger a un gran volumen de refugiados iraquíes, que en 2006 se convirtieron en la segunda minoría más grande del país, después de los finlandeses. En 2015, el gobierno socialdemócrata de Stefan Löfven abrió la frontera a los refugiados sirios, que llegaron en masa, huyendo de la Guerra Civil siria y del empuje de Daesh.

Esta sucesión de olas de inmigrantes de Oriente Medio agravaron algunos problemas: en muchos vecindarios, los llegados de fuera no se sienten como en Suecia, principalmente porque estos fueron construidos para "no ser Suecia"; además, la difícil integración y los trabajos mal pagados alimentan las pandillas y el crimen organizado. Todo esto llevó a Löfven a aplicar una política de migración más estricta en 2017, aceptando menos solicitantes de asilo y comenzando a expulsar a aquellos cuyas solicitudes de asilo habían sido denegadas.

Como se puede ver la tendencia en Suecia es abrir las fronteras a la inmigración cuando esta es necesaria y cerrarlas cuando esta comienza a provocar tensiones sociales.

Orígenes de la población inmigrante

Suecia se ha convertido en una sociedad étnicamente muy diversa, donde casi el 22% de la población tiene antecedentes extranjeros. Hasta 2015, la mayor minoría étnica en eran los finlandeses, que a finales del pasado siglo superaban los 200.000. A raíz de la guerra de Irak y de la crisis migratoria siria, las personas procedentes de Oriente Medio han pasado a ser el mayor grupo.

En la actualidad, el 8% de los habitantes de Suecia procede de un país de mayoría musulmana –básicamente de Siria e Irak, pero también de Irán–, si bien solo el 1,4% de la población practica la religión musulmana (alrededor de 140.000 personas en 2017), pues también existen inmigrantes procedentes de esos países con otras adscripciones religiosas, como cristianos, drusos, yazidis o zoroastrianos. Estos números pueden haber aumentado ligeramente, si bien no para provocar cambios muy drásticos en la demografía.

A pesar de no ser especialmente numerosa, la comunidad musulmana ha generado atención mediática a raíz de diversas polémicas. En 2006, Mahmoud Aldebe, miembro del Consejo Musulmán de Suecia, planteó por carta a los partidos políticos del Riksdag y al Gobierno sueco demandas especialmente controvertidas, como derecho a vacaciones islámicas específicas, financiamiento público especial para la construcción de mezquitas, que todos los divorcios entre parejas musulmanas sean aprobados por un imán, y que a los imanes se les permita enseñar el Islam a niños musulmanes en escuelas públicas. Esas demandas fueron rechazadas por las autoridades y la clase política de Suecia. También se ha dado el caso de que algunas asociaciones musulmanas o mezquitas han invitado a predicadores radicales, como Haitham al-Haddad o Said Rageahs, cuyas conferencias fueron finalmente prohibidas.

Áreas Vulnerables y crimen organizado

El Gobierno sueco ha designado algunos barrios como Áreas Vulnerables (Utsatt Område). No son propiamente “No-Go Zones”, porque en ellas tanto los agentes policiales, como los servicios sanitarios o los medios de comunicación pueden entrar. Se trata de áreas de menor seguridad que exigen una mayor atención de las autoridades.

Algunas de ellas se encuentran en Malmö, ciudad con la mayor tasa de criminalidad del país, principalmente debido a su ubicación. Malmö se encuentra al otro lado del puente de Oresund, que conecta Dinamarca con Suecia y es la única ruta por tierra entre Suecia y el continente sin tener que rodear el Báltico. Allí diversas pandillas y mafias participan en el tráfico de drogas y de personas, al tiempo que se enfrentan entre ellas en una pugna por el control del espacio. Grupos de este tipo también actúan en Rotterdam, en relación a la actividad generada por su importante puerto.

A pesar de la impresión dada por ciertos mensajes contrarios a la inmigración, la comisión de delitos en Suecia se encuentra en niveles parecidos a los de 2006. Después de ese año el número de delitos descendió, para subir de nuevo en 2010 y 2012. Podría establecerse una relación entre ese ascenso y la crisis económica, que supuso un aumento del desempleo, pero no está tan clara su vinculación con los registros de inmigración. La llegada de iraquíes en 2005 no conllevó una mayor inseguridad en las calles de Suecia y tampoco lo ha hecho la recepción de sirios en los recientes años. La tasa de homicidios en Suecia es de 1,1 por cada cien mil habitantes –por debajo de otros muchos países europeos–, y hay más delitos registrados por nativos suecos que por extranjeros, según el Consejo Nacional Sueco para la Prevención del Delito.

No obstante, las mafias que operan en Suecia se componen en su mayoría de ciertos grupos étnicos. Su formación se derivó especialmente de la llegada de personas de Yugoslavia, tanto de trabajadores de la década de 1970 como de refugiados de las guerras balcánicas de la década de 1990. El principal de esos grupos, conocido como Yugo Mafia, está hoy liderada por Milan Ševo, apodado “El Padrino de Estocolmo”. Otros grupos son K-Falangen y Naserligan, compuestos por albaneses; la Legión Werefolf, formada por sudamericanos, y los Gangsters, originales por los asirios (minoría cristiana de Siria). No obstante, uno de los más grandes es Brödraskapet o la Hermandad, fundada en 1995, con más de 700 miembros que en su totalidad son suecos nativos y con mucha presencia en las cárceles suecas.

![Movimientos migratorios de Suecia entre 1850 y 2007. En rojo, llegada de inmigrantes; en azul, salida de emigrantes [Wikipedia-Koyos] Movimientos migratorios de Suecia entre 1850 y 2007. En rojo, llegada de inmigrantes; en azul, salida de emigrantes [Wikipedia-Koyos]](/documents/10174/16849987/sueci-migracion-tabla.png)

Movimientos migratorios de Suecia entre 1850 y 2007. En rojo, llegada de inmigrantes; en azul, salida de emigrantes [Wikipedia-Koyos]

Terrorismo

Desde 2011 en Suecia se han producido tres ataques terroristas; un cuarto ataque pudo se evitado al ser detectada con tiempo su preparación. El primero fue realizado por Anton Lundin Pettersson, un neonazi sueco que en 2015 atacó la Escuela Trollhättan, donde mató a cuatro personas, todas ellas inmigrantes. El siguiente fue perpetrado por el Movimiento de Resistencia Nórdica, una organización neonazi, que actuó contra un centro de refugiados y el café de una organización de izquierdas; en el ataque solo se produjo un herido. El tercero, el más conocido, fue perpetuado en 2017 por un hombre de Uzbekistán aparentemente reclutado por Daesh, que arremetió con un camión contra viandantes en el centro de Estocolmo, matando a cinco personas e hiriendo a catorce.

De los tres atentados, solo uno tuvo motivación yihadista, a diferencia del peso que el terrorismo islamista ha tenido en otros países europeos con mayor población musulmana. En cualquier caso, la segregación que se vive en algunas comunidades y el adoctrinamiento radical que se da en ellas llevó a jóvenes suecos musulmanes a marchar a Siria para encuadrarse en Daesh y las autoridades siguen de cerca su posible retorno.

Aciertos y errores

Durante mucho tiempo, desde la izquierda europea se puso a Suecia como ejemplo de modelo socialdemócrata exitoso; ahora, desde ciertos grupos de derecha, se le pone como ejemplo de multiculturalismo fallido. Probablemente ambas afirmaciones son una exageración con fines partidistas. No obstante, lo cierto es que Suecia cuenta con un bienestar generoso que está costando mantener, y que en su también generosa apertura de fronteras ha cometido errores que no han facilitado la integración de la nueva población. Todo parece indicar que Löfven continua el camino que empezó en 2017 y se ha aumentado la presencia policial en las calles así como un endurecimiento en las políticas de inmigración, siguiendo a su vez las políticas hechas en Dinamarca.

Tiempo tendrá que pasar para ver qué resultados estas políticas tendrán en una futura Suecia.

*En la mitología nórdica, el Valhalla es un enorme y majestuoso salón al que, en la otra vida, aspiran a entrar los héroes

[Winston Lord, Kissinger on Kissinger. Reflections on Diplomacy, Grand Strategy, and Leadership. All Points Books. New York, 2019. 147 p.]

RESEÑA / Emili J. Blasco

|

A sus 96 años, Henry Kissinger ve publicado otro libro en gran parte suyo: la transcripción de una serie de largas entrevistas en relación a las principales actuaciones exteriores de la Administración Nixon, en la que sirvió como consejero de seguridad nacional y secretario de Estado. Aunque él mismo ya ha dejado amplios escritos sobre esos momentos y ha aportado documentación para que otros escriban en torno a ellos –como en el caso de la biografía de Niall Ferguson, cuyo primer tomo apareció en 2015–, Kissinger ha querido volver sobre aquel periodo de 1969-1974 para ofrecer una síntesis de los principios estratégicos que motivaron las decisiones entonces adoptadas. No se aportan novedades, pero sí detalles que pueden interesar a los historiadores de esa época.

La obra no responde a un deseo de última hora de Kissinger de influir sobre una determinada lectura de su legado. De hecho, la iniciativa de mantener los diálogos que aquí se transcriben no partió de él. Se enmarca, no obstante, en una ola de reivindicación de la presidencia de Richard Nixon, cuya visión estratégica en política internacional quedó empañada por el Watergate. La Fundación Nixon promovió la realización de una serie de vídeos, que incluyeron diversas entrevistas a Kissinger, llevadas a cabo a lo largo de 2016. Estas fueron conducidas por Winston Lord, estrecho colaborador de Kissinger durante su etapa en la Casa Blanca y en el Departamento de Estado, junto a K. T. McFarland, entonces funcionaria a sus órdenes (y, durante unos meses, número dos del Consejo de Seguridad Nacional con Donald Trump). Pasados más de dos años, esa conversación con Kissinger se publica ahora en una obra de formato pequeño y breve extensión. Sus últimos libros habían sido “China” (2011) y “Orden Mundial” (2014).

El relato oral de Kissinger se ocupa aquí de unos pocos asuntos que centraron su actividad como gran artífice de la política exterior estadounidense: la apertura a China, la distensión con Rusia, el fin de la guerra de Vietnam y la mayor implicación en Oriente Medio. Aunque la conversación entra en detalles y aporta diversas anécdotas, lo sustancial es lo que más allá de esas concreciones puede extraerse: son las “reflexiones sobre diplomacia, gran estrategia y liderazgo” que indica el subtítulo del libro. Pudiera resultar cansino volver a leer la intrahistoria de una actuación diplomática sobre la que el propio protagonista ya ha sido prolífico, pero en esta ocasión se ofrecen reflexiones que trascienden el periodo histórico específico, que para muchos puede quedar ya muy lejos, así como interesantes recomendaciones sobre los procesos de toma de decisión en posiciones de liderazgo.

Kissinger aporta algunas claves, por ejemplo, sobre por qué en Estados Unidos se ha consolidado el Consejo de Seguridad Nacional como instrumento de acción exterior del presidente, con vida autónoma –y en ocasiones conflictiva– respecto al Departamento de Estado. La Administración Nixon fue su gran impulsora, siguiendo la sugerencia de Eisenhower, de quien Nixon había sido vicepresidente: la coordinación interdepartamental en política exterior difícilmente podía ya hacerse desde un departamento –la Secretaría de Estado–, sino que debía llevarse a cabo desde la propia Casa Blanca. Mientras el consejero de Seguridad Nacional puede concentrarse en aquellas actuaciones que más le interesan al presidente, el secretario de Estado está obligado a una mayor dispersión, teniendo que atender multitud de frentes. Por lo demás, a diferencia de la mayor prontitud del Departamento de Defensa en secundar al comandante en jefe, el aparato del Departamento de Estado, habituado a elaborar múltiples alternativas para cada asunto internacional, puede tardar en asumir plenamente la dirección impuesta desde la Casa Blanca.

En cuanto a estrategia negociadora, Kissinger rechaza la idea de fijar privadamente un máximo objetivo y después ir recortándolo poco a poco, como las rodajas de un salami, a medida que se va alcanzando el final de la negociación. Propone en cambio fijar desde el principio las metas básicas que se desearían lograr –añadiendo tal vez un 5% por aquello de que algo habrá que ceder– y dedicar largo tiempo a explicárselas a la otra parte, con la idea de llegar a un entendimiento conceptual. Kissinger aconseja comprender bien qué mueve a la otra parte y cuáles son sus propios objetivos, pues “si tú impones tus intereses, sin vincularlos a los intereses de los otros, no podrás sostener tus esfuerzos”, dado que al final de la negociación las partes tienen que estar dispuestas a apoyar lo logrado.

Como en otras ocasiones, Kissinger no se abroga en exclusiva el mérito de los éxitos diplomáticos de la Administración Nixon. Si bien la prensa y cierta parte de la academia ha otorgado mayor reconocimiento al antiguo profesor de Harvard, el propio Kissinger ha insistido en que fue Nixon quien marcó decididamente las políticas, cuya maduración habían previamente realizado ambos por separado, antes de colaborar en la Casa Blanca. No obstante, es quizás en este libro donde las palabras de Kissinger más ensalzan al antiguo presidente, tal vez por haberse realizado en el marco de una iniciativa nacida desde la Fundación Nixon.

“La contribución fundamental de Nixon fue establecer un patrón de pensamiento en política exterior, que es seminal”, asegura Kissinger. Según este, la manera tradicional de abordar la acción exterior estadounidense había sido segmentar los asuntos para intentar resolverlos como problemas individuados, haciendo su resolución la cuestión misma. “Nixon fue –dejando aparte a los Padres Fundadores y, yo diría, a Teddy Roosevelt– el presidente estadounidense que pensó la política exterior como gran estrategia. Para él, la política exterior era la mejora estructural de la relación entre los países de modo que el equilibrio de sus intereses propios promoviera la paz global y la seguridad de Estados Unidos. Y pensó sobre esto en términos de relativo largo alcance”.

Quienes tengan poca simpatía por Kissinger –un personaje de apasionados defensores pero también de acérrimos críticos– verán en esta obra otro ejercicio de autocomplacencia y enaltecimiento propio del exconsejero. Quedarse en ese estadio sería desaprovechar una obra que contiene interesantes reflexiones y creo que completa bien el pensamiento de alguien de tanta relevancia en la historia de las relaciones internacionales. Lo que de afirmación personal pueda tener la publicación se refiere más bien a Winston Lord, que aquí se reivindica como mano derecha de Kissinger en aquella época: en las primeras páginas aparece completa la foto de la entrevista de Nixon y Mao, cuyos márgenes aparecieron cortados en su día por la Casa Blanca para que la presencia de Lord no molestara al secretario de Estado, que no fue invitado al histórico viaje a Pekín.

▲ Special forces (Pixabay)

ESSAY / Roberto Ramírez and Albert Vidal

During the Cold War, Offensive Realism, a theory elaborated by John Mearsheimer, appeared to fit perfectly the international system (Pashakhanlou, 2018). Thirty years after the fall of the Soviet Union, this does not seem to be the case anymore. From the constructivist point of view, Offensive Realism makes certain assumptions about the international system which deserve to be questioned (Wendt, 2008).The purpose of this paper is thus to make a critique of Mearsheimer’s concept of anarchy in the international system. The development of this idea by Mearsheimer can be found in the second chapter of his book ‘The Tragedy of Great Power Politics’.

The essay will begin with a brief summary of the core tenets of the said chapter and how they relate to Offensive Realism more generally. Afterwards, the constructivist theory proposed by Alexander Wendt will be presented. Then, it will be argued from a constructivist approach that the international sphere is the result of a construction and it does not necessarily lead to war. Next, the different types of anarchies that Wendt presents will be described, as an argument against the single and uniform international system that is presented by Neorealists. Lastly, the essay will make a case for the importance of shared values and ideologies, and how this is oftentimes underestimated by offensive realists.

Mearsheimer’s work and Offensive Realism

‘The Tragedy of Great Power Politics’ has become one of the most decisive books in the field of International Relations after the Cold War and has developed the theory of offensive realism to an unprecedented extent. In this work, Mearsheimer enumerates the five assumptions on which offensive realism rests (Mearsheimer, 2014):

1. The international system is anarchic. Mearsheimer understand anarchy as an ordering principle that comprises independent states which have no central authority above them. There is no “government over governments”.

2. Great powers inherently possess offensive military capabilities; which means that there will always be a possibility of mutual destruction. Thus, every state could be a potential enemy.

3. States are never certain of other states’ intentions. All states may be benign, but states could never be sure about that, since their intention could change all of a sudden.

4. Survival is the primary goal of great powers and it dominates other motives. Once a state is conquered, any chances to achieve other goals disappear.

5. Great powers are rational actors, because when it comes to international policies, they consider how their behavior could affect other’s behavior and vice versa.

The problem is, according to Mearsheimer, that when those five assumptions come together, they create strong motivations for great powers to behave offensively, and three patterns of behavior originate (Mearsheimer, 2007).

First, great powers fear each other, which is a motivating force in world politics. States look with suspicion to each other in a system with little room for trust. Second, states aim to self-help actions, as they tend to see themselves as vulnerable and lonely. Thus, the best way to survive in this self-help world is to be selfish. Alliances are only temporary marriages of convenience because states are not willing to subordinate their interest to international community. Lastly, power maximization is the best way to ensure survival. The stronger a state is compared to their enemies, the less likely it is to be attacked by them. But, how much power is it necessary to amass, so that a state will not be attacked by others? As that is something very difficult to know, the only goal can be to achieve hegemony.

A Glimpse of Constructivism, by Alexander Wendt

According to Alexander Wendt, one of the main constructivist authors, there are two main tenets that will help understand this approach:

The first one goes as follows: “The identities and interests of purposive actors are constructed by these shared ideas rather than given by nature” (Wendt, 2014). Constructivism has two main referent objects: the individual and the state. This theory looks into the identity of the individuals of a nation to understand the interests of a state. That is why there is a need to understand what identity and interests are, according to constructivism, and what are they used for.

i. Identity is understood by constructivism as the social interactions that people of a nation have with each other, which shape their ideas. Constructivism tries to understand the identity of a group or a nation through its historical record, cultural things and sociology. (McDonald, 2012).

ii. A state’s interest is a cultural construction and it has to do with the cultural identity of its citizens. For example, when we see that a state is attacking our state’s liberal values, we consider it a major threat; however, when it comes to buglers or thieves, we don’t get alarmed that much because they are part of our culture. Therefore, when it comes to international security, what may seem as a threat for a state may not be considered such for another (McDonald, 2012).

The second tenet says that “the structures of human association are determined primarily by shared ideas rather than material forces”. Once that constructivism has analyzed the individuals of a nation and knows the interest of the state, it is able to examine how interests can reshape the international system (Wendt, 2014). But, is the international system dynamic? This may be answered by dividing the international system in three elements:

a) States, according to constructivism, are composed by a material structure and an idealist structure. Any modification in the material structure changes the ideal one, and vice versa. Thus, the interest of a state will differ from those of other states, according to their identity (Theys, 2018).

b) Power, understood as military capabilities, is totally variable. Such variation may occur in quantitative terms or in the meaning given to such military capabilities by the idealist structure (Finnemore, 2017). For instance, the friendly relationship between the United States (US) and the United Kingdom is different from the one between the US and North Korea, because there is an intersubjectivity factor to be considered (Theys, 2018).

c) International anarchy, according to Wendt, does not exist as an “ordering principle” but it is “what states make of it” (Wendt, 1995). Therefore, the anarchical system is mutable.

The international system and power competition: a wrong assumption?

The first argument will revolve around the following neorealist assumption: the international system is anarchic by nature and leads to power competition, and this cannot be changed. To this we add the fact that states are understood as units without content, being qualitatively equal.

What would constructivists answer to those statements? Let’s begin with an example that illustrates the weakness of the neorealist argument: to think of states as blank units is problematic. North Korea spends around $10 billion in its military (Craw, 2019), and a similar amount is spent by Taiwan. But the former is perceived as a dangerous threat while the latter isn’t. According to Mearsheimer, we should consider both countries equally powerful and thus equally dangerous, and we should assume that both will do whatever necessary to increase their power. But in reality, we do not think as such: there is a strong consensus on the threat that North Korea represents, while Taiwan isn’t considered a serious threat to anyone (it might have tense relations with China, but that is another issue).

The key to this puzzle is identity. And constructivism looks on culture, traditions and identity to better understand what goes on. The history of North Korea, the wars it has suffered, the Japanese attitude during the Second World War, the Juche ideology, and the way they have been educated enlightens us, and helps us grasp why North Korea’s attitude in the international arena is aggressive according to our standards. One could scrutinize Taiwan’s past in the same manner, to see why has it evolved in such way and is now a flourishing and open society; a world leader in technology and good governance. Nobody would see Taiwan as a serious threat to its national security (with the exception of China, but that is different).

This example could be brought to a bigger scale and it could be said that International Relations are historically and socially constructed, instead of being the inevitable consequence of human nature. It is the states the ones that decide how to behave, and whether to be a good ally or a traitor. And thus the maxim ‘anarchy is what states make of it’, which is better understood in the following fragment (Copeland, 2000; p.188):

‘Anarchy has no determinant "logic," only different cultural instantiations. Because each actor's conception of self (its interests and identity) is a product of the others' diplomatic gestures, states can reshape structure by process; through new gestures, they can reconstitute interests and identities toward more other-regarding and peaceful means and ends.’

We have seen Europe succumb under bloody wars for centuries, but we have also witnessed more than 70 years of peace in that same region, after a serious commitment of certain states to pursue a different goal. Europe has decided to do something else with the anarchy that it was given: it has constructed a completely different ecosystem, which could potentially expand to the rest of the international system and change the way we understand international relations. This could obviously change for the better or for the worse, but what matters is that it has been proven how the cycle of inter-state conflict and mutual distrust is not inevitable. States can decide to behave otherwise and trust in their neighbors; by altering the culture that constitutes the system, they can set the foundations for non-egoistic mind-sets that will bring peace (Copeland, 2000). It will certainly not be easy to change, but it is perfectly possible.

As it was said before, constructivism does not deny an initial state of anarchy in the international system; it simply affirms that it is an empty vessel which does not inevitably lead to power competition. Wendt affirms that whether a system is conflictive or peaceful is not decided by anarchy and power, but by the shared culture that is created through interaction (Copeland, 2000).

Three different ‘anarchies’

Alexander Wendt describes in his book ‘Social Theory of International Politics’ the three cultures of anarchy that have embedded the international system for the past centuries (Wendt, 1999). Each of these cultures has been constructed by the states, thanks to their interaction and acceptance of behavioral norms. Such norms continuously shape states’ interests and identities.

Firstly, the Hobbesian culture dominated the international system until the 17th century; where the states saw each other as dangerous enemies that competed for the acquisition of power. Violence was used as a common tool to resolve disputes. Then, the Lockean culture emerged with the Treaty of Westphalia (1648): here states became rivals, and violence was still used, but with certain restrains. Lastly, the Kantian culture has appeared with the spread of democracies. In this culture of anarchy, states cooperate and avoid using force to solve disputes (Copeland, 2000). The three examples that have been presented show how the Neorealist assumption that anarchy is of one sort, and that it drives toward power competition cannot be sustained. According to Copeland (2000; p.198-199), ‘[…] if states fall into such conflicts, it is a result of their own social practices, which reproduce egoistic and military mind-sets. If states can transcend their past realpolitik mindset, hope for the future can be restored.’

Ideal structures are more relevant than what you think

One of the common assertions of Offensive Realism is that “[…] the desire for security and fear of betrayal will always override shared values and ideologies” (Seitz, 2016). Constructivism opposes such assertion, and brands it as too simplistic. In reality, it has been repeatedly proven wrong. A common history, shared values, and even friendship among states are some things that Offensive Realism purposefully ignores and does not contemplate.

Let’s illustrate it with an example. Country A has presumed power strength of 7. Country B has a power strength of 15. Offensive Realism would say that country A is under the threat of an attack by country B, which is much more powerful and if it has the chance, it will conquer country A. No other variables or structures are taken into account, and that will happen inexorably. Such assertion, under today’s dynamics is considered quite absurd. Let’s put a counter-example: who in earth thinks that the US is dying to conquer Canada and will do so when the first opportunity comes up? Why doesn’t France invade Luxembourg, if one take into account how easy and lucrative this enterprise might be? Certainly, there are other aspects such as identities and interests that offensive realism has ignored, but are key in shaping states’ behavior in the international system.

That is how shared values (an ideal structure) oftentimes overrides power concerns (a material structure) when two countries that are asymmetrically powerful become allies and decide to cooperate.

Conclusion

After deepening into the understanding that offensive realists have of anarchy in the international system, this essay has covered the different arguments that constructivists employ to face such conception. To put it briefly, it has been argued that the international system is the result of a construction, and it is shared culture that decides whether anarchy will lead to conflict or peace. To prove such argument, the three different types of anarchies that have existed in the relatively recent times have been described. Finally, a case has been made for the importance of shared values and ideologies over material structures, which is generally dismissed by offensive realists.

Although this has not been an exhaustive critique of Offensive Realism, the previous insights may have provided certain key ideas that will contribute to the conversation. Our understanding of the theory of constructivism will certainly shape the way we tackle crisis and the way we conceive international relations. It is then tremendously important that one knows in which cases it ought to be applied, so that we do not rely completely on a particular theory which becomes our new object of veneration; since this may have dreadful consequences.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Copeland, D. C. (2000). The Constructivist Challenge to Structural Realism: A Review Essay. The MIT Press, 25, 287–212. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2626757

Craw, V. (2019). North Korea military spending: Country spends 22 per cent of GDP. Retrieved from https://www.news.com.au/world/asia/north-korea-spends-whopping-22-per-cent-of-gdp-on-military-despite-blackouts-and-starving-population/news-story/c09c12d43700f28d389997ee733286d2

D. Williams, P. (2012). Security Studies: An Introduction. (Routledge, Ed.) (2nd ed.).

Finnemore, M. (2017). National Interests in International Society (pp. 6 - 7).

McDonald, M. (2012). Security, the environment and emancipation (pp. 48 - 59). New York: Routledge.

Mearsheimer, J. (2014). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. (WW Norton & Co, Ed.). New York.

Mearsheimer. (2007). Tragedy of great power politics (pp. 29 - 54). [Place of publication not identified]: Academic Internet Pub Inc.

Pashakhanlou, A. (2018). Realism and fear in international relations. [Place of publication not identified]: Palgrave Macmillan.

Seitz, S. (2016). A Critique of Offensive Realism. Retrieved March 2, 2019, from https://politicstheorypractice.com/2016/03/06/a-critique-of-offensive-realism/

Theys, S. (2018). Introducing Constructivism in International Relations Theory. Retrieved from https://www.e-ir.info/2018/02/23/introducing-constructivism-in-international-relations-theory/

Walt, S. M. (1987). The Origins of Alliances. (C. U. Press, Ed.). Ithaca.

Wendt, A. (1995). Constructing international politics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wendt, A. (2008). Anarchy is what States make of it (pp. 399 - 403). Farnham: Ashgate.

Wendt, A. (2014). Social theory of international politics (p. 1). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wendt, A. (2014). Social theory of international politics (p. 29 - 33). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

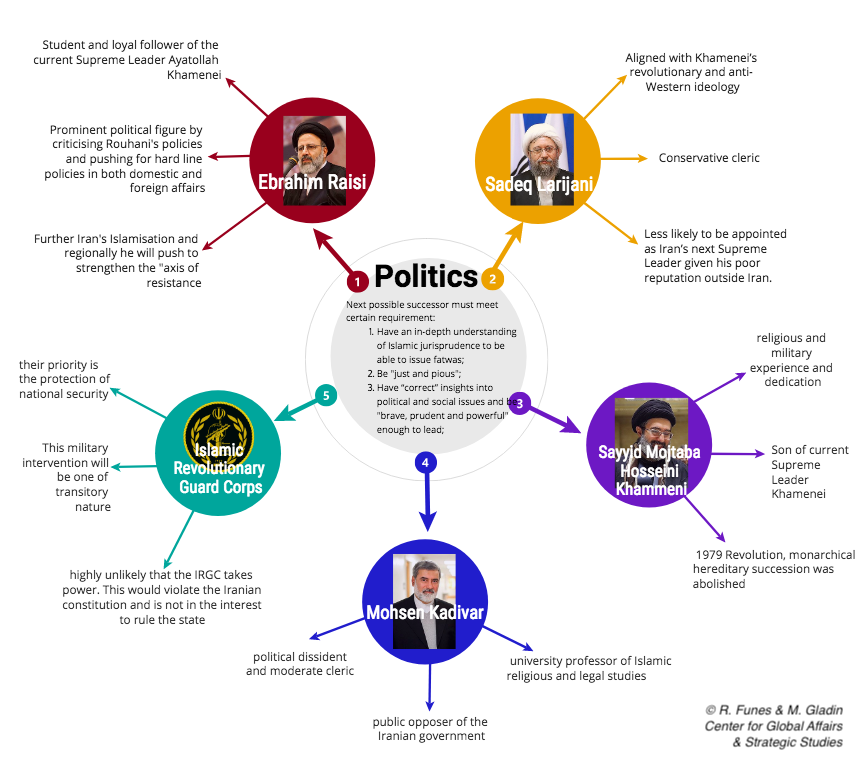

The struggle for power has already started in the Islamic Republic in the midst of US sanctions and ahead a new electoral cycle

![Ayatollah Ali Khamenei speaking to Iranian Air Force personnel, in 2016 [Wikipedia] Ayatollah Ali Khamenei speaking to Iranian Air Force personnel, in 2016 [Wikipedia]](/documents/10174/16849987/khamenei-blog.jpg)

▲ Ayatollah Ali Khamenei speaking to Iranian Air Force personnel, in 2016 [Wikipedia]

ANALYSIS / Rossina Funes and Maeve Gladin

The failing health of Supreme Leader Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei, 89, brings into question the political aftermath of his approaching death or possible step-down. Khamenei’s health has been a point of query since 2007, when he temporarily disappeared from the public eye. News later came out that he had a routine procedure which had no need to cause any suspicions in regards to his health. However, the question remains as to whether his well-being is a fantasy or a reality. Regardless of the truth of his health, many suspect that he has been suffering prostate cancer all this time. Khamenei is 89 years old –he turns 80 in July– and the odds of him continuing as active Supreme Leader are slim to none. His death or resignation will not only reshape but could also greatly polarize the successive politics at play and create more instability for Iran.

The next possible successor must meet certain requirements in order to be within the bounds of possible appointees. This political figure must comply and follow Khamenei’s revolutionary ideology by being anti-Western, mainly anti-American. The prospective leader would also need to meet religious statues and adherence to clerical rule. Regardless of who that cleric may be, Iran is likely to be ruled by another religious figure who is far less powerful than Khamenei and more beholden to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Additionally, Khamenei’s successor should be young enough to undermine the current opposition to clerical rule prevalent among many of Iran’s youth, which accounts for the majority of Iran’s population.

In analyzing who will head Iranian politics, two streams have been identified. These are constrained by whether the current Supreme Leader Khamenei appoints his successor or not, and within that there are best and worst case scenarios.

Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi

Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi had been mentioned as the foremost contender to stand in lieu of Iranian Supreme Leader Khamenei. Shahroudi was a Khamenei loyalist who rose to the highest ranks of the Islamic Republic’s political clerical elite under the supreme leader’s patronage and was considered his most likely successor. A former judiciary chief, Shahroudi was, like his patron, a staunch defender of the Islamic Revolution and its founding principle, velayat-e-faqih (rule of the jurisprudence). Iran’s domestic unrest and regime longevity, progressively aroused by impromptu protests around the country over the past year, is contingent on the political class collectively agreeing on a supreme leader competent of building consensus and balancing competing interests. Shahroudi’s exceptional faculty to bridge the separated Iranian political and clerical establishment was the reason his name was frequently highlighted as Khamenei’s eventual successor. Also, he was both theologically and managerially qualified and among the few relatively nonelderly clerics viewed as politically trustworthy by Iran’s ruling establishment. However, he passed away in late December 2018, opening once again the question of who was most likely to take Khamenei’s place as Supreme Leader of Iran.

However, even with Shahroudi’s early death, there are still a few possibilities. One is Sadeq Larijani, the head of the judiciary, who, like Shahroudi, is Iraqi born. Another prospect is Ebrahim Raisi, a former 2017 presidential candidate and the custodian of the holiest shrine in Iran, Imam Reza. Raisi is a student and loyalist of Khamenei, whereas Larijani, also a hard-liner, is more independent.

1. MOST LIKELY SCENARIO, REGARDLESS OF APPOINTMENT

1.1 Ebrahim Raisi

In a more likely scenario, Ebrahim Raisi would rise as Iran’s next Supreme Leader. He meets the requirements aforementioned with regards to the religious status and the revolutionary ideology. Fifty-eight-years-old, Raisi is a student and loyal follower of the current Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei. Like his teacher, he is from Mashhad and belongs to its famous seminary. He is married to the daughter of Ayatollah Alamolhoda, a hardline cleric who serves as Khamenei's representative of in the eastern Razavi Khorasan province, home of the Imam Reza shrine.

Together with his various senior judicial positions, in 2016 Raisi was appointed the chairman of Astan Quds Razavi, the wealthy and influential charitable foundation which manages the Imam Reza shrine. Through this appointment, Raisi developed a very close relationship with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which is a known ideological and economic partner of the foundation. In 2017, he moved into the political sphere by running for president, stating it was his "religious and revolutionary responsibility". He managed to secure a respectable 38 percent of the vote; however, his contender, Rouhani, won with 57 percent of the vote. At first, this outcome was perceived as an indicator of Raisi’s relative unpopularity, but he has proven his detractors wrong. After his electoral defeat, he remained in the public eye and became an even more prominent political figure by criticizing Rouhani's policies and pushing for hard-line policies in both domestic and foreign affairs. Also, given to Astan Quds Foundation’s extensive budget, Raisi has been able to secure alliances with other clerics and build a broad network that has the ability to mobilize advocates countrywide.

Once he takes on the role of Supreme Leader, he will continue his domestic and regional policies. On the domestic front, he will further Iran's Islamisation and regionally he will push to strengthen the "axis of resistance", which is the anti-Western and anti-Israeli alliance between Iran, Syria, Hezbollah, Shia Iraq and Hamas. Nevertheless, if this happens, Iran would live on under the leadership of yet another hardliner and the political scene would not change much. Regardless of who succeeds Khamenei, a political crisis is assured during this transition, triggered by a cycle of arbitrary rule, chaos, violence and social unrest in Iran. It will be a period of uncertainty given that a great share of the population seems unsatisfied with the clerical establishment, which was also enhanced by the current economic crisis ensued by the American sanctions.

1.2 Sadeq Larijani

Sadeq Larijani, who is fifty-eight years old, is known for his conservative politics and his closeness to the supreme guide of the Iranian regime Ali Khamenei and one of his potential successors. He is Shahroudi’s successor as head of the judiciary and currently chairs the Expediency Council. Additionally, the Larijani family occupies a number of important positions in government and shares strong ties with the Supreme Leader by being among the most powerful families in Iran since Khamenei became Supreme Leader thirty years ago. Sadeq Larijani is also a member of the Guardian Council, which vetos laws and candidates for elected office for conformance to Iran’s Islamic system.

Formally, the Expediency Council is an advisory body for the Supreme Leader and is intended to resolve disputes between parliament and a scrutineer body, therefore Larijani is well informed on the way Khamenei deals with governmental affairs and the domestic politics of Iran. Therefore, he meets the requirement of being aligned with Khamenei’s revolutionary and anti- Western ideology, and he is also a conservative cleric, thus he complies with the religious figure requirement. Nonetheless, he is less likely to be appointed as Iran’s next Supreme Leader given his poor reputation outside Iran. The U.S. sanctioned Larijani on the grounds of human rights violations, in addition to “arbitrary arrests of political prisoners, human rights defenders and minorities” which “increased markedly” since he took office, according to the EU who also sanctioned Larijani in 2012. His appointment would not be a strategic decision amidst the newly U.S. imposed sanctions and the trouble it has brought upon Iran. Nowadays, the last thing Iran wants is that the EU also turn their back to them, which would happen if Larijani rises to power. However it is still highly plausible that Larijani would be the second one on the list of prospective leaders, only preceded by Raisi.

|

2. LEAST LIKELY SCENARIO: SUCCESSOR NOT APPOINTED

2.1 Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

The IRGC’s purpose is to preserve the Islamic system from foreign interference and protect from coups. As their priority is the protection of national security, the IRGC necessarily will take action once Khamenei passes away and the political sphere becomes chaotic. In carrying out their role of protecting national security, the IRGC will act as a support for the new Supreme Leader. Moreover, the IRGC will work to stabilize the unrest which will inevitably occur, regardless of who comes to power. It is our estimate that the new Supreme Leader will have been appointed by Khamenei before death, and thus the IRGC will do all in their power to protect him. In the unlikely case that Khamenei does not appoint a successor, we believe that there are two unlikely options of ruling that could arise.

The first, and least likely, being that the IRGC takes rule. Moreover, it is highly unlikely that the IRGC takes power. This would violate the Iranian constitution and is not in the interest to rule the state. What they are interested in is having a puppet figure who will satisfy their interests. As the IRGC's main role is national security, in the event that Khamenei does not appoint a successor and the country goes into political and social turmoil, the IRGC will without a doubt step in. This military intervention will be one of transitory nature, as the IRGC does not pretend to want direct political power. Once the Supreme Leader is secured, the IRGC will go back to a relatively low profile.

In the very unlikely event that a Supreme Leader is not predetermined, the IRGC may take over the political regime of Iran, creating a military dictatorship. If this were to happen, there would certainly be protests, riots and coups. It would be very difficult for an opposition group to challenge and defeat the IRGC, but there would be attempts to overcome it. This would be a regime of temporary nature, however, the new Supreme Leader would arise from the scene that the IRGC had been protecting.

2.2 Mohsen Kadivar

In addition, political dissident and moderate cleric Mohsen Kadivar is a plausible candidate for the next Supreme Leader. Kadivar’s rise to political power in Iran would be a black swan, as it is extremely unlikely, however, the possibility should not be dismissed. His election would be highly unlikely due to the fact that he is a vocal critic of clerical rule and has been a public opposer of the Iranian government. He has served time in prison for speaking out in favor of democracy and liberal reform as well as publicly criticizing the Islamic political system. Moreover, he has been a university professor of Islamic religious and legal studies throughout the United States. As Kadivar goes against all requirements to become successor, he is highly unlikely to become Supreme Leader. It is also important to keep in mind that Khamenei will most likely appoint a successor, and in that scenario, he will appoint someone who meets the requirements and of course is in line with what he believes. In the rare case that Khamenei does not appoint a successor or dies before he gets the chance to, a political uprising is inevitable. The question will be whether the country uprises to the point of voting a popular leader or settling with someone who will maintain the status quo.

In the situation that Mohsen Kadivar is voted into power, the Iranian political system would change drastically. For starters, he would not call himself Supreme Leader, and would instill a democratic and liberal political system. Kadivar and other scholars which condemn supreme clerical rule are anti-despotism and advocate for its abolishment. He would most likely establish a western-style democracy and work towards stabilizing the political situation of Iran. This would take more years than he will allow himself to remain in power, however, he will probably stay active in the political sphere both domestically as well as internationally. He may be secretary of state after stepping down, and work as both a close friend and advisor of the next leader of Iran as well as work for cultivating ties with other democratic countries.

2.3 Sayyid Mojtaba Hosseini Khamenei

Khamenei's son, Sayyid Mojtaba Hosseini Khamenei is also rumored to be a possible designated successor. His religious and military experience and dedication, along with being the son of Khamenei gives strong reason to believe that he may be appointed Supreme Leader by his father. However, Mojtaba is lacking the required religious status. The requirements of commitment to the IRGC as well as anti-American ideology are not questioned, as Mojtaba has a well-known strong relationship with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Mojtaba studied theology and is currently a professor at Qom Seminary in Iran. Nonetheless, it is unclear as to whether Mojtaba’s religious and political status is enough to have him considered to be the next Supreme Leader. In the improbable case that Khamenei names his son to be his successor, it would be possible for his son to further commit to the religious and political facets of his life and align them with the requirements of being Supreme Leader.

This scenario is highly unlikely, especially considering that in the 1979 Revolution, monarchical hereditary succession was abolished. Mojtaba has already shown loyalty to Iran when taking control of the Basij militia during the uproar of the 2009 elections to halt protests. While Mojtaba is currently not fit for the position, he is clearly capable of gaining the needed credentials to live up to the job. Despite his potential, all signs point to another candidate becoming the successor before Mojtaba.

3. PATH TO DEMOCRACY

Albeit the current regime is supposedly overturned by an uprising or new appointment by the current Supreme Leader Khamenei, it is expected that any transition to democracy or to Western-like regime will take a longer and more arduous process. If this was the case, it will be probably preceded by a turmoil analogous to the Arab Springs of 2011. However, even if there was a scream for democracy coming from the Iranian population, the probability that it ends up in success like it did in Tunisia is slim to none. Changing the president or the Supreme Leader does not mean that the regime will also change, but there are more intertwined factors that lead to a massive change in the political sphere, like it is the path to democracy in a Muslim state.

[Francis Fukuyama, Identidad. La demanda de dignidad y las políticas de resentimiento. Deusto, Barcelona, 2019. 208 p.]

RESEÑA / Emili J. Blasco

|

El deterioro democrático que hoy vemos en el mundo está generando una literatura propia como la que, sobre el fenómeno contrario, se suscitó con la primavera democrática vivida tras la caída del Muro de Berlín (lo que Huntington llamó la tercera ola democratizadora). En aquel momento de optimismo, Francis Fukuyama popularizó la idea del “fin de la historia” –la democracia como instancia final en la evolución de las instituciones humanas–; hoy, en este otoño democrático, Fukuyama advierte en un nuevo ensayo del riesgo de que lo identitario, despojado de las salvaguardas liberales, fagocite los demás valores si sigue en manos del resurgente nacionalismo populista.

La alerta no es nueva. De ella no se movió Huntington, que ya en 1996 publicó su Choque de civilizaciones, destacando la potencia motriz del nacionalismo; luego, en los últimos años, diversos autores se han referido al retroceso de la marea democrática. Fukuyama cita la expresión de Larry Diamond “recesión democrática”, constatando que frente al salto dado entre 1970 y el comienzo del nuevo milenio (se pasó de 35 a 120 democracias electorales) hoy el número ha decrecido.

El último célebre teórico de las relaciones internacionales en escribir al respecto ha sido John Mearsheimer, quien en The Great Delusion constata cómo el mundo se da hoy cuenta de la ingenuidad de pensar que la arquitectura liberal iba a dominar la política doméstica y exterior de las naciones. Para Mearsheimer, el nacionalismo emerge de nuevo con fuerza como alternativa. Eso ya se observó justo tras descomposición del Bloque del Este y de la URSS, con la guerra de los Balcanes como ejemplo paradigmático, pero la democratización de Europa central y oriental y su rápido ingreso en la OTAN llevaron al engaño (delusion).

Han sido la personalidad y las políticas del actual morador de la Casa Blanca lo que a algunos pensadores estadounidenses, entre ellos Fukuyama, ha puesto en alerta. “Este libro no se habría escrito si Donald J. Trump no hubiera sido elegido presidente en noviembre de 2016”, advierte el profesor de la Universidad de Stanford, director de su Centro sobre Democracia, Desarrollo y Estado de Derecho. En su opinión, Trump “es tanto un producto como un contribuidor de la decadencia” democrática y constituye un exponente del fenómeno más amplio del nacionalismo populista.

Fukuyama define ese populismo a partir de sus dirigentes: “Los líderes populistas buscan usar la legitimidad conferida por las elecciones democráticas para consolidar su poder. Reivindican una conexión directa y carismática con el pueblo, que a menudo es definido en estrechos términos étnicos que excluyen importantes partes de la población. No les gusta las instituciones y buscan socavar los pesos y contrapesos que limitan el poder personal de un líder en una democracia liberal moderna: tribunales, parlamento, medios independientes y una burocracia no partidista”.

Probablemente es injusto echar en cara a Fukuyama algunas conclusiones de El final de la historia y el último hombre (1992), un libro a menudo malinterpretado y sacado de su clave teórica. El autor luego ha concretado más su pensamiento sobre el desarrollo institucional de la organización social, especialmente en sus títulos Origins of Political Order (2011) y Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Present Day (2014). Ya en este último apuntaba el riesgo de regresión, en particular a la vista de la polarización y falta de consenso en la política estadounidense.

En Identidad, Fukuyama considera que el nacionalismo no étnico ha sido una fuerza positiva en las sociedades siempre que se ha basado en la construcción de identidades alrededor de valores políticos liberales y democráticos (pone el ejemplo de India, Francia, Canadá y Estados Unidos). Ello porque la identidad, que facilita el sentido de comunidad y pertenencia, puede contribuir a desarrollar seis funciones: seguridad física, calidad del gobierno, promoción del desarrollo económico, aumento del radio de confianza, mantenimiento de una protección social que mitiga las desigualdades económicas y facilitación de la democracia liberal misma.

No obstante –y este puede ser el toque de atención que pretende el libro–, en un momento de recesión de los valores liberales y democráticos estos van a acompañar cada vez menos al fenómeno identitario, de forma que este puede pasar en muchos casos de integrador a excluyente.

[Pablo Simón, El príncipe moderno: Democracia, política y poder. Debate, Barcelona 2018, 272 páginas]

RESEÑA / Alejandro Palacios

|

Las relaciones internacionales son guiadas en cada Estado por una serie de líderes e, indirectamente, por partidos políticos que son elegidos de manera más o menos democrática por los ciudadanos. Por tanto, la alta volatilidad del voto que vemos extenderse hoy en nuestras sociedades repercute indirectamente en la deriva del sistema internacional. Este libro trata de hacer un repaso a los sistemas políticos de algunos países para tratar de explicar, en esencia, cómo los ciudadanos interactúan dentro de cada sistema político. La pertinencia del libro está, pues, más que justificada.

De hecho, al entender las tendencias de voto de los ciudadanos, moldeadas por las divisiones sociales y el sistema político al que se enfrenten, nos podemos hacer una idea de por qué han emergido líderes políticamente tan radicales como Trump o Bolsonaro. A modo de ejemplo, no resulta lo mismo votar en un sistema mayoritario que hacerlo dentro de un sistema proporcional. Tampoco votan igual jóvenes y adultos, habitantes de la ciudad y del campo ni los hombres y las mujeres (divisiones conocidas como la triple brecha electoral).

El autor del libro, el politólogo español Pablo Simón, toma como punto de partida la Gran Recesión de 2008, momento en el cual comienzan a emerger nuevas opciones políticas fomentadas, en parte, por la pérdida de confianza tanto en los partidos políticos tradicionales como en el sistema en sí. Paralelamente, la obra intenta reivindicar la importancia de la existencia de una ciencia política que, como tal, sea capaz de tomar una afirmación popular sobre un tema relevante, contrastarla empíricamente y extraer conclusiones en su mayoría generales que ayuden a confirmar o desmentir dicha creencia.